Current Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in the Management of Rectal Cancer Above the Age of 80

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Measures and Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Features

3.2. Treatment Patterns and Pathological Differences

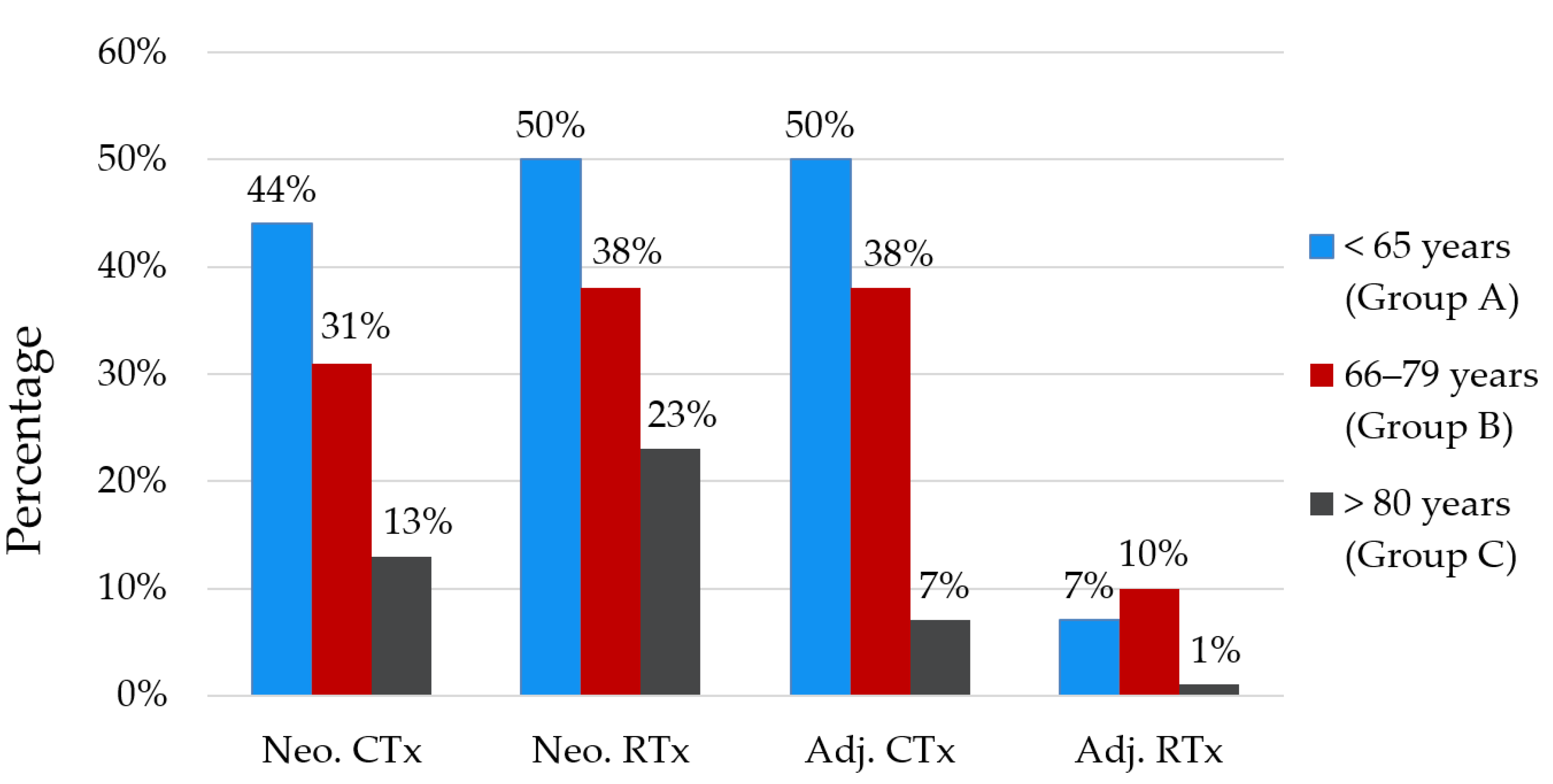

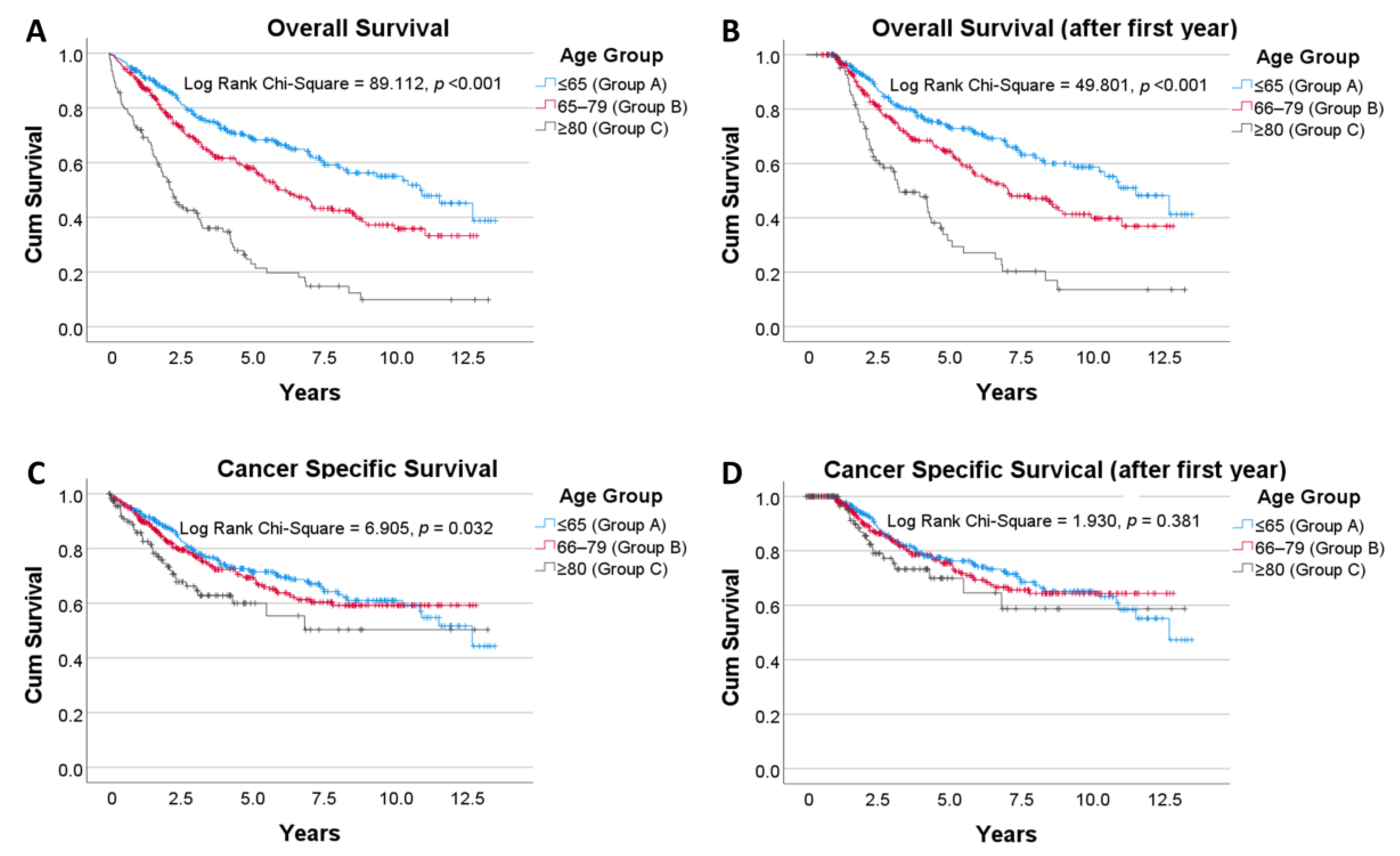

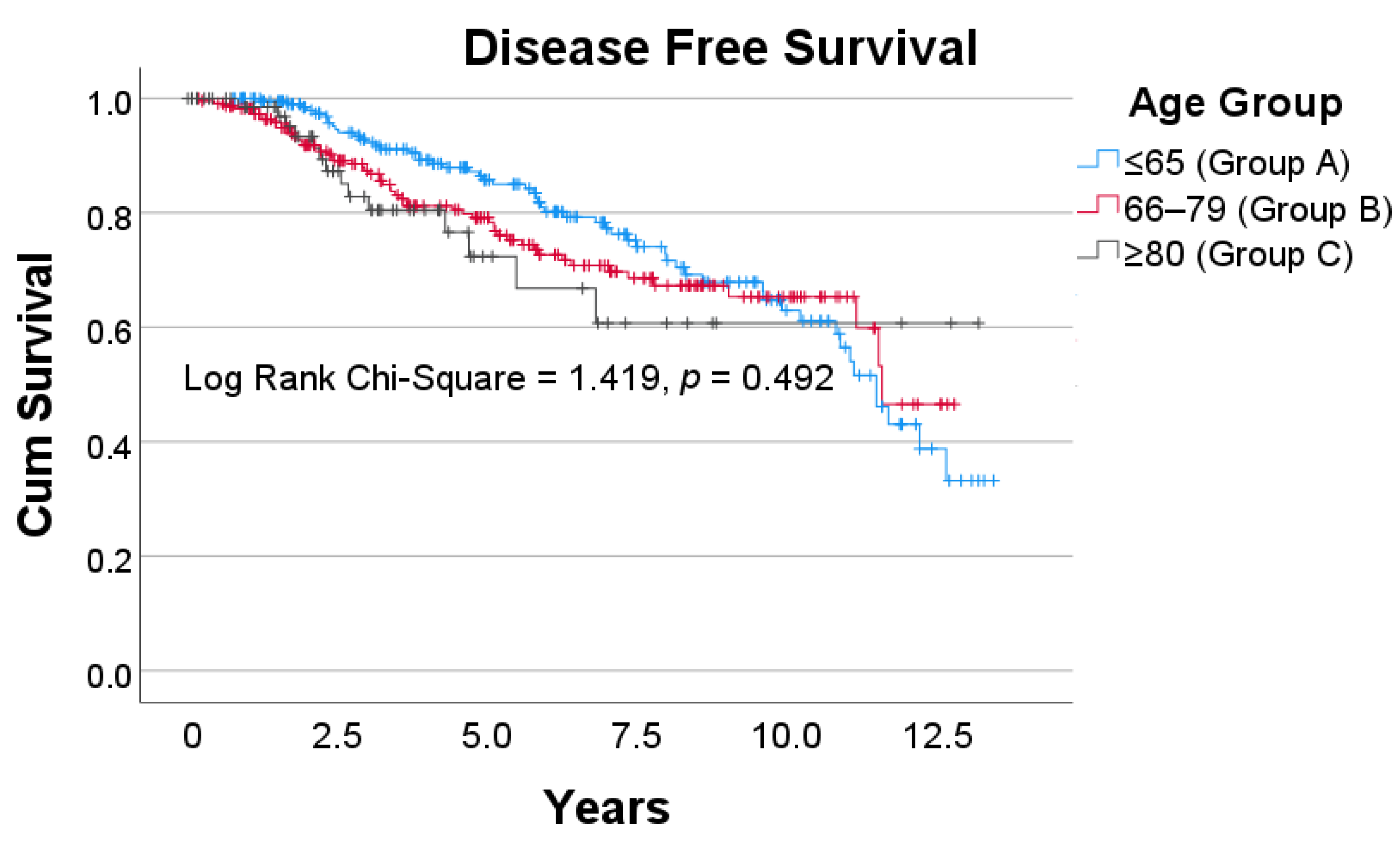

3.3. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Safiri, S.; Sepanlou, S.G.; Ikuta, K.S.; Bisigano, C.; Salimzadeh, H.; Delavari, A.; Ansari, R.; Roshandel, G.; Merat, S.; Fitzmaurice, C.; et al. The global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Sierra, M.S.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 2017, 66, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichael, D.; Audisio, R.A.; Glimelius, B.; de Gramont, A.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Haller, D.; Köhne, C.H.; Rostoft, S.; Lemmens, V.; Mitry, E.; et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer in older patients: International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) consensus recommendations 2013. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolle, S.; Smets, E.M.A.; Hamaker, M.E.; Loos, E.F.; van Weert, J.C.M. Medical decision making for older patients during multidisciplinary oncology team meetings. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugolini, G.; Ghignone, F.; Zattoni, D.; Veronese, G.; Montroni, I. Personalized surgical management of colorectal cancer in elderly population. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 3762–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, J.; Walsh, P.; Kevans, D.; Cooney, T.; O’Hanlon, S.; Nolan, B.; White, A.; McDermott, E.; Sheahan, K.; O’Shea, D.; et al. Determinants of short- and long-term survival from colorectal cancer in very elderly patients. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2014, 5, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bos, A.; Kortbeek, D.; van Erning, F.N.; Zimmerman, D.D.E.; Lemmens, V.; Dekker, J.W.T.; Maas, H. Postoperative mortality in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: The impact of age, time-trends and competing risks of dying. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIHW. Cancer Rankings Data Visualisation. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/cancer-rankings-data-visualisation (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Montroni, I.; Ugolini, G.; Saur, N.M.; Spinelli, A.; Rostoft, S.; Millan, M.; Wolthuis, A.; Daniels, I.R.; Hompes, R.; Penna, M.; et al. Personalized management of elderly patients with rectal cancer: Expert recommendations of the European Society of Surgical Oncology, European Society of Coloproctology, International Society of Geriatric Oncology, and American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1685–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.Y.; Kawamura, Y.J.; Tokomitsu, A.; Tang, T. Assessment for frailty is useful for predicting morbidity in elderly patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection whose comorbidities are already optimized. Am. J. Surg. 2012, 204, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørum, M.; Gregersen, M.; Jensen, K.; Meldgaard, P.; Damsgaard, E.M.S. Frailty status but not age predicts complications in elderly cancer patients: A follow-up study. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamini, N.; Giani, A.; Famularo, S.; Montuori, M.; Giardini, V.; Gianotti, L. Should radical surgery for rectal cancer be offered to elderly population? A propensity-matching analysis on short- and long-term outcomes. Updates Surg. 2020, 72, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roder, D.; Karapetis, C.S.; Wattchow, D.; Moore, J.; Singhal, N.; Joshi, R.; Keefe, D.; Fusco, K.; Powell, K.; Eckert, M.; et al. Colorectal cancer treatment and survival over three decades at four major public hospitals in South Australia: Trends by age and in the elderly. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basili, G.; Lorenzetti, L.; Biondi, G.; Preziuso, E.; Angrisano, C.; Carnesecchi, P.; Roberto, E.; Goletti, O. Colorectal cancer in the elderly. Is there a role for safe and curative surgery? ANZ J. Surg. 2008, 78, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, K.W.; Oh, H.K.; Kim, D.W.; Kang, S.B.; Song, C.; Kim, J.S. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for elderly patients with locally advanced rectal cancer-a real-world outcome study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 46, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorica, F.; Cartei, F.; Carau, B.; Berretta, S.; Spartà, D.; Tirelli, U.; Santangelo, A.; Maugeri, D.; Luca, S.; Leotta, C.; et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy on older and oldest elderly rectal cancer patients. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 49, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manceau, G.; Karoui, M.; Werner, A.; Mortensen, N.J.; Hannoun, L. Comparative outcomes of rectal cancer surgery between elderly and non-elderly patients: A systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, e525–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhangu, A.; Kiran, R.P.; Audisio, R.; Tekkis, P. Survival outcome of operated and non-operated elderly patients with rectal cancer: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 40, 1510–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, C.J.; Yabroff, K.R.; Warren, J.L.; Zeruto, C.; Chawla, N.; Lamont, E.B. Trends in the Treatment of Metastatic Colon and Rectal Cancer in Elderly Patients. Med. Care 2016, 54, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldvaser, H.; Katz Shroitman, N.; Ben-Aharon, I.; Purim, O.; Kundel, Y.; Shepshelovich, D.; Shochat, T.; Sulkes, A.; Brenner, B. Octogenarian patients with colorectal cancer: Characterizing an emerging clinical entity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ramos, D.; Simon-Monterde, L.; Queralt-Martin, R.; Suelves-Piqueres, C.; Menor-Duran, P.; Escrig-Sos, J. Breast cancer in octogenarian. Are we doing our best? A population-registry based study. Breast 2018, 38, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.B.; Worhunsky, D.J.; Squires, M.H., 3rd; Jin, L.X.; Spolverato, G.; Votanopoulos, K.I.; Schmidt, C.; Weber, S.; Bloomston, M.; Cho, C.S.; et al. Outcomes of Gastric Cancer Resection in Octogenarians: A Multi-institutional Study of the U.S. Gastric Cancer Collaborative. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 4371–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Z.; Zhang, W.; Meng, R.-G.; Fu, C.-G. Massive presacral bleeding during rectal surgery: From anatomy to clinical practice. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 4039–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, G.D.; Morgan, M.J.; Wong, S.-K.C.; Gatenby, A.H.; Fulham, S.B.; Ahmed, K.W.; Toh, J.W.T.; Hanna, M.; Hitos, K.; the South Western Sydney Colorectal Tumor Group. Improved Short-term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Versus Open Resection for Colon and Rectal Cancer in an Area Health Service: A Multicenter Study. Dis. Colon Rectum 2012, 55, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, S.I.; Yu, C.S.; Kim, G.S.; Lee, J.L.; Yoon, Y.S.; Kim, C.W.; Lim, S.-B.; Kim, J.C. The Role of Diverting Stoma After an Ultra-low Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer. Ann. Coloproctol. 2013, 29, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.L.; Chang, S.C.; Lin, T.C.; Chen, W.S.; Jiang, J.K.; Wang, H.S.; Yang, S.H.; Liang, W.Y.; Lin, J.K. Differences in clinicopathological characteristics of colorectal cancer between younger and elderly patients: An analysis of 322 patients from a single institution. Am. J. Surg. 2011, 202, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunitake, H.; Zingmond, D.S.; Ryoo, J.; Ko, C.Y. Caring for octogenarian and nonagenarian patients with colorectal cancer: What should our standards and expectations be? Dis. Colon Rectum 2010, 53, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, B.S.; Suchitra, M.M.; Srinivasa Rao, P.; Kumar, V.S. Serum tumor markers in advanced stages of chronic kidney diseases. Saudi. J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2019, 30, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, N.M.; Qwaider, Y.Z.; Goldstone, R.N.; Stafford, C.E.; Cauley, C.E.; Francone, T.D.; Ricciardi, R.; Bordeianou, L.G.; Berger, D.L.; Kunitake, H. Octogenarians present with a less aggressive phenotype of colon adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2020, 168, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Choi, S.J.; Ryoo, S.B.; Park, J.W.; Park, K.J.; Oh, J.H.; Kang, S.B.; Park, H.C.; Heo, S.C.; et al. Survival paradox between stage IIB/C (T4N0) and stage IIIA (T1-2N1) colon cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, B.-C.; Sun, L.-R.; Wang, J.-W.; Fu, X.-H.; Zhang, S.-Z.; Poston, G.; Ding, K.-F. TNM staging of colorectal cancer should be reconsidered by T stage weighting. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 5104–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.N.; Balentine, C.J.; Marshall, C.L.; Wilks, J.A.; Anaya, D.; Artinyan, A.; Berger, D.H.; Albo, D. Minimally invasive surgery improves short-term outcomes in elderly colorectal cancer patients. J. Surg. Res. 2011, 166, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaraki, F.; Vafaie, M.; Behboo, R.; Maghsoodi, N.; Esmaeilpour, S.; Safaee, A. Quality of life outcomes in patients living with stoma. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2012, 18, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, M.; Merino, S.; Caro, A.; Feliu, F.; Escuder, J.; Francesch, T. Treatment of colorectal cancer in the elderly. World J. Gastrointest Oncol. 2015, 7, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haak, H.E.; Maas, M.; Lambregts, D.M.J.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Beets, G.L. Is watch and wait a safe and effective way to treat rectal cancer in older patients? Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.; Sun Myint, A.; Athanasiou, T.; Faiz, O.; Martin, A.P.; Collins, B.; Smith, F.M. Avoiding Radical Surgery in Elderly Patients With Rectal Cancer Is Cost-Effective. Dis. Colon Rectum 2017, 60, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F.M.; Rao, C.; Oliva Perez, R.; Bujko, K.; Athanasiou, T.; Habr-Gama, A.; Faiz, O. Avoiding radical surgery improves early survival in elderly patients with rectal cancer, demonstrating complete clinical response after neoadjuvant therapy: Results of a decision-analytic model. Dis. Colon Rectum 2015, 58, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, R.J.; Taylor, J.C.; Downing, A.; Spencer, K.; Finan, P.J.; Audisio, R.A.; Carrigan, C.M.; Selby, P.J.; Morris, E.J.A. Rectal cancer in old age -is it appropriately managed? Evidence from population-based analysis of routine data across the English national health service. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenal-Vera, J.J.; Tinoco-Carrasco, C.; del-Villar-Negro, A.; Labarga-Rodríguez, F.; Delgado-Mucientes, A.; Cítores, M.A. Colorectal cancer in the elderly: Characteristics and short term results. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2011, 103, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cai, X.; Wu, H.; Peng, J.; Zhu, J.; Cai, S.; Cai, G.; Zhang, Z. Tolerability and outcomes of radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer in elderly patients aged 70 years and older. Radiat. Oncol. 2013, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, J.W.T.; van den Broek, C.B.M.; Bastiaannet, E.; van de Geest, L.G.M.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Liefers, G.J. Importance of the first postoperative year in the prognosis of elderly colorectal cancer patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokutani, Y.; Mizushima, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Rakugi, H.; Doki, Y.; Mori, M. Prediction of Postoperative Complications Following Elective Surgery in Elderly Patients with Colorectal Cancer Using the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Dig. Surg. 2016, 33, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffmann, L.; Ozcan, S.; Schwarz, F.; Lange, J.; Prall, F.; Klar, E. Colorectal cancer in the elderly: Surgical treatment and long-term survival. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2008, 23, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, N.M.; Schiphorst, A.H.; Maas, H.A.; Zimmerman, D.D.; van den Bos, F.; Pronk, A.; Borel Rinkes, I.H.; Hamaker, M.E. Colorectal Cancer Resections in the Oldest Old Between 2011 and 2012 in The Netherlands. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 1875–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, Y.H.M.; Vermeer, N.C.A.; Iversen, L.H.; van Eycken, E.; Guren, M.G.; Mroczkowski, P.; Martling, A.; Codina Cazador, A.; Johansson, R.; Vandendael, T.; et al. Treatment and survival of rectal cancer patients over the age of 80 years: A EURECCA international comparison. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.M.; Raissouni, S.; Mercer, J.; Kumar, A.; Goodwin, R.; Heng, D.Y.; Tang, P.A.; Doll, C.; MacLean, A.; Powell, E.; et al. Clinical outcomes of elderly patients receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2102–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.; O’Brien, P.; Zhao, Y.; Hopman, W.M.; Lamond, N.; Ramjeesingh, R. Adjuvant treatment in older patients with rectal cancer: A population-based review. Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25, e499–e506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derwinger, K.; Kodeda, K.; Gerjy, R. Age aspects of demography, pathology and survival assessment in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010, 30, 5227–5231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kristjansson, S.R.; Nesbakken, A.; Jordhøy, M.S.; Skovlund, E.; Audisio, R.A.; Johannessen, H.O.; Bakka, A.; Wyller, T.B. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A prospective observational cohort study. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2010, 76, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stornes, T.; Wibe, A.; Endreseth, B.H. Complications and risk prediction in treatment of elderly patients with rectal cancer. Int J. Colorectal. Dis. 2016, 31, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rønning, B.; Wyller, T.B.; Nesbakken, A.; Skovlund, E.; Jordhøy, M.S.; Bakka, A.; Rostoft, S. Quality of life in older and frail patients after surgery for colorectal cancer-A follow-up study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2016, 7, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souwer, E.T.; Moos, S.I.; van Rooden, C.J.; Bijlsma, A.Y.; Bastiaannet, E.; Steup, W.H.; Dekker, J.W.T.; Fiocco, M.; van den Bos, F.; Portielje, J.E. Physical performance has a strong association with poor surgical outcome in older patients with colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völkel, V.; Draeger, T.; Schnitzbauer, V.; Gerken, M.; Benz, S.; Klinkhammer-Schalke, M.; Fürst, A. Surgical treatment of rectal cancer patients aged 80 years and older-a German nationwide analysis comparing short- and long-term survival after laparoscopic and open tumor resection. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Qu, W.; He, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y. Laparoscopic surgery after neoadjuvant therapy in elderly patients with rectal cancer. JBUON 2017, 22, 869–874. [Google Scholar]

- Schreckenbach, T.; Zeller, M.V.; El Youzouri, H.; Bechstein, W.O.; Woeste, G. Identification of factors predictive of postoperative morbidity and short-term mortality in older patients after colorectal carcinoma resection: A single-center retrospective study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2018, 9, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X. Predictive risk factors for anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of rectal cancer in elderly patients over 80 years old: An analysis of 288 consecutive patients. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 17, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruns, E.R.; van den Heuvel, B.; Buskens, C.J.; van Duijvendijk, P.; Festen, S.; Wassenaar, E.B.; van der Zaag, E.S.; Bemelman, W.A.; van Munster, B.C. The effects of physical prehabilitation in elderly patients undergoing colorectal surgery: A systematic review. Colorectal. Dis. 2016, 18, O267–O277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, T.L.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Langenberg, J.C.M.; de Lepper, C.; Wielders, D.; Seerden, T.C.J.; de Lange, D.C.; Wijsman, J.H.; Ho, G.H.; Gobardhan, P.D.; et al. Multimodal prehabilitation to reduce the incidence of delirium and other adverse events in elderly patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: An uncontrolled before-and-after study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall (N = 699) | Group A ≤65 Years (N = 288, 41%) | Group B 66–79 Years (N = 293, 42%) | Group C ≥80 Years (N = 118, 17%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Stage | 0.240 | ||||

| I | 152 (22%) | 49 (17%) | 67 (23%) | 36 (31%) | |

| IIA | 91 (13%) | 31 (11%) | 42 (14%) | 18 (15%) | |

| IIB | 9 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| IIC | 11 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (2%) | 2 (2%) | |

| IIIA | 50 (7%) | 20 (7%) | 23 (8%) | 7 (6%) | |

| IIIB | 188 (27%) | 84 (29%) | 75 (26%) | 29 (25%) | |

| IIIC | 64 (9%) | 29 (10%) | 30 (10%) | 5 (4.2%) | |

| IVA | 79 (11%) | 42 (15%) | 26 (9%) | 11 (9%) | |

| IVB | 55 (8%) | 25 (9%) | 21 (7%) | 9 (8%) | |

| CEA (ng/mL), mean ± SD | 129.4 ± 1394.1 | 60.8 ± 336.7 | 174.8 ± 1999.6 | 193.3 ± 1207.7 | 0.609 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 28.0 ± 5.5 | 28.7 ± 6.2 | 27.7 ± 5.2 | 26.6 ± 4.2 | 0.002 |

| ECOG a | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 243 (60%) | 130 (71%) | 103 (59%) | 10 (20%) | |

| 1 | 123 (30%) | 48 (26%) | 57 (33%) | 18 (37%) | |

| 2 | 28 (7%) | 5 (3%) | 12 (7%) | 11 (22%) | |

| 3 | 13 (3%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (2%) | 9 (18%) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

| Presentation a | 0.081 | ||||

| Symptomatic | 565 (91%) | 231 (89%) | 229 (90%) | 105 (96%) | |

| Asymptomatic | 58 (9%) | 28 (11%) | 26 (10%) | 4 (4%) | |

| Morphology | 0.543 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | 615 (88%) | 252 (88%) | 258 (88%) | 105 (89%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma in TBA/TVA | 56 (8%) | 24 (8%) | 24 (8%) | 8 (7%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma mucinous | 24 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 11 (4%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Other | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | |

| Distance FAV (mm), mean ± SD | 59 ± 46 | 64 ± 48 | 59 ± 46 | 46 ± 40 | 0.001 |

| Overall | Group A ≤65 Years | Group B 66–79 Years | Group C ≥80 Years | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery a | <0.001 | ||||

| LAR/ULAR | 366 (52%) | 178 (62%) | 153 (52%) | 35 (30%) | |

| APR | 147 (21%) | 60 (21%) | 64 (22%) | 23 (20%) | |

| Hartmann’s | 29 (4%) | 10 (4%) | 8 (3%) | 11 (9%) | |

| Pelvic Exenteration | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | |

| Other | 43 (6%) | 8 (3%) | 20 (7%) | 15 (13%) | |

| No Surgery | 110 (16%) | 30 (10%) | 46 (16%) | 34 (29%) | |

| Treatment for those with no surgery b | 0.005 | ||||

| Palliative chemotherapy | 22 (20%) | 8 (27%) | 13 (28%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Palliative radiotherapy | 20 (18%) | 2 (7%) | 8 (17%) | 10 (29%) | |

| Palliative chemoradiotherapy | 30 (37%) | 13 (43%) | 10 (22%) | 7 (21%) | |

| No treatment | 38 (35%) | 7 (23%) | 15 (33%) | 16 (47%) |

| Overall (N = 589) | Group A ≤65 Years (N = 258) | Group B 66–79 Years (N = 247) | Group C ≥80 Years (N = 84) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph Nodes retrieved a | 0.0498 | ||||

| <12 | 118 (21%) | 48 (19%) | 54 (24%) | 16 (22%) | |

| ≥12 | 435 (79%) | 203 (81%) | 176 (76%) | 56 (78%) | |

| Resection Margin a | 0.004 | ||||

| R0 | 531 (94%) | 239 (94%) | 226 (95%) | 66 (88%) | |

| R1 | 32 (5%) | 15 (6%) | 11 (5%) | 6 (8%) | |

| R2 | 4 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Resection Margin (mm) | 0.091 | ||||

| mean ± SD | 10.7 ± 11.5 | 11.7 ± 12.3 | 10.4 ± 11.2 | 8.5 ± 8.8 | |

| Tumour size (mm), mean ± SD | 34.0 ± 18.4 | 31.5 ± 17.4 | 35.9 ± 19.7 | 36.5 ± 16.1 | 0.019 |

| Histology Grade a | 0.019 | ||||

| Well-differentiated | 46 (8%) | 25 (10%) | 14 (5%) | 7 (8%) | |

| Mod differentiated | 292 (81%) | 215 (81%) | 201 (79%) | 76 (86%) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 70 (11%) | 24 (9%) | 41 (16%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion a | 0.058 | ||||

| No LVI | 417 (73%) | 180 (72%) | 178 (74%) | 59 (78%) | |

| LVI present | 89 (16%) | 33 (13%) | 44 (18%) | 12 (16%) | |

| LVI with EMVI | 63 (11%) | 38 (15%) | 20 (8%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Perineural invasion a | 77 (14%) | 46 (19%) | 23 (10%) | 8 (12%) | 0.013 |

| Neoadjuvant Treatment b | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 201 (34%) | 113 (44%) | 77 (31%) | 11 (13%) | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | 241 (41%) | 129 (50%) | 93 (38%) | 19 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Adjuvant Treatment b | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 229 (39%) | 128 (50%) | 95 (38%) | 6 (7%) | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | 44 (7%) | 19 (7%) | 24 (10%) | 1 (1%) | 0.037 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mourad, A.P.; De Robles, M.S.; Putnis, S.; Winn, R.D.R. Current Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in the Management of Rectal Cancer Above the Age of 80. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1388-1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28020132

Mourad AP, De Robles MS, Putnis S, Winn RDR. Current Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in the Management of Rectal Cancer Above the Age of 80. Current Oncology. 2021; 28(2):1388-1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28020132

Chicago/Turabian StyleMourad, Ali P., Marie Shella De Robles, Soni Putnis, and Robert D.R. Winn. 2021. "Current Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in the Management of Rectal Cancer Above the Age of 80" Current Oncology 28, no. 2: 1388-1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28020132

APA StyleMourad, A. P., De Robles, M. S., Putnis, S., & Winn, R. D. R. (2021). Current Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in the Management of Rectal Cancer Above the Age of 80. Current Oncology, 28(2), 1388-1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28020132