Bullying in Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Analyzing Students’ Social Status and Student–Teacher Relationship Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. ADHD

1.1.1. ADHD and Bullying

1.1.2. Bullying

1.2. Peer Relationships at School

1.3. The Student–Teacher Relationship

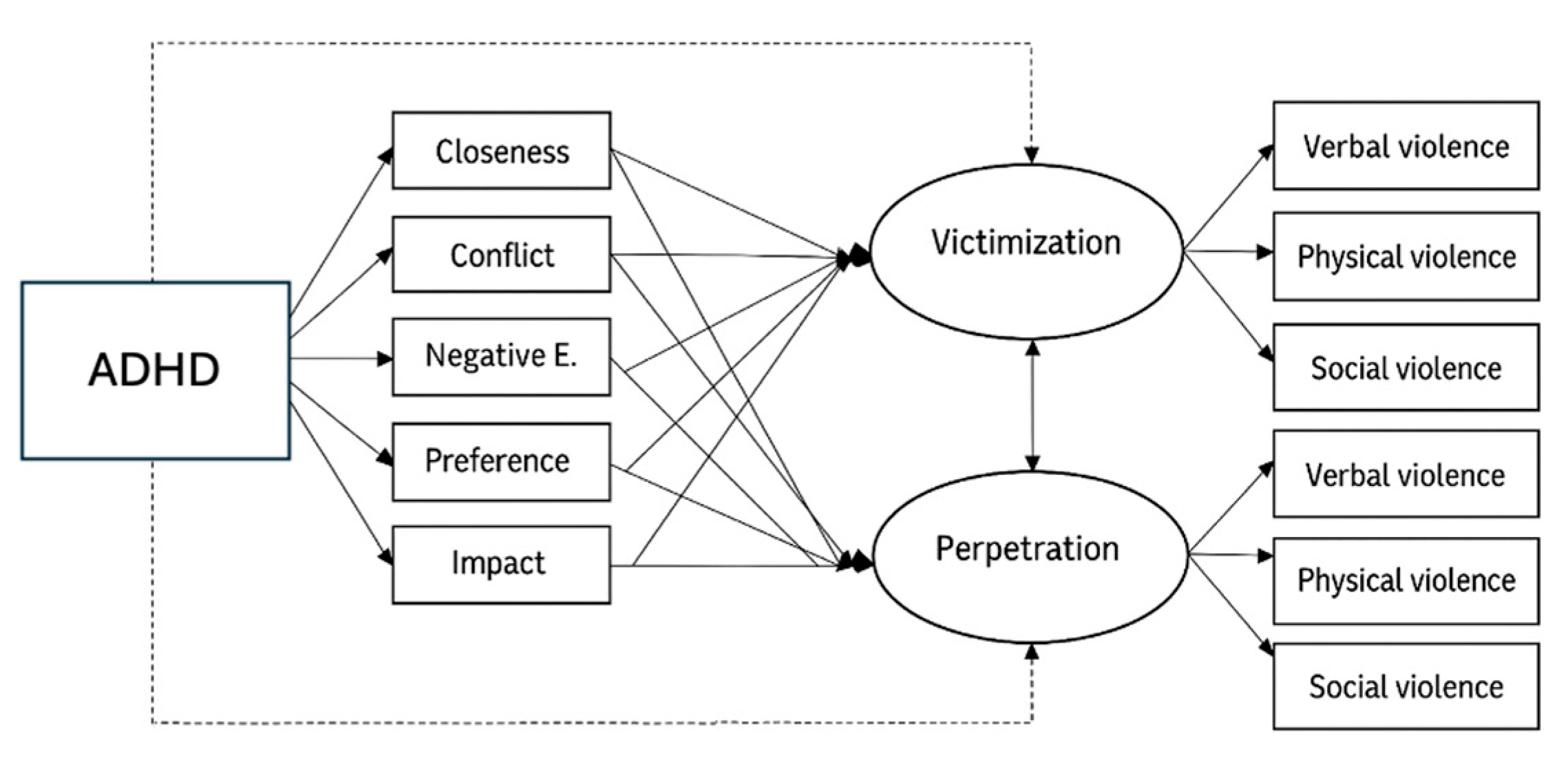

1.4. Aims of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Practical and Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| AIP | Italian Association for Psychology |

| APRI | Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| IEP | Individual Education Plans |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| LD | Linear Dichroism |

| Mplus | Muthén & Muthén statistical software (Version 8) for Structural Equation Modeling |

| PDP | Piani Didattici Personalizzati |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDQ | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| SI | Social Impact |

| SP | Social Preference |

| SPARTS | Student Perception of Affective Relationship with Teacher Scale |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| STR | Student–Teacher Relationship |

| STRS | Student–Teacher Relationship Scale |

| TD | Typical Development |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780890425558/9780890425572. [Google Scholar]

- von Gontard, A.; Hussong, J.; Yang, S.S.; Chase, J.; Franco, I.; Wright, A. Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Incontinence in Children and Adolescents: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Intellectual Disability—A Consensus Document of the International Children’s Continence Society. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2022, 41, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraçaydın, G.; Ruisch, I.H.; van Rooij, D.; Sprooten, E.; Franke, B.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Hoekstra, P.J. Shared Genetic Etiology Between ADHD, Task-Related Behavioral Measures and Brain Activation During Response Inhibition in a Youth ADHD Case–Control Study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 274, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Paalanen, L.; Melymuk, L.; Katsonouri, A.; Kolossa-Gehring, M.; Tolonen, H. The Association Between ADHD and Environmental Chemicals—A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A.; Murphy, K.R.; Fischer, M. ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson, M.L.; Claussen, A.H.; Bitsko, R.H.; Katz, S.M.; Newsome, K.; Blumberg, S.J.; Ghandour, R. ADHD Prevalence Among US Children and Adolescents in 2022: Diagnosis, Severity, Co-Occurring Disorders, and Treatment. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2024, 53, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Muñoz, L.; Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Peñuelas-Calvo, I.; Delgado-Gómez, D.; Miguélez-Fernández, C.; López-González, S.; Porras-Segovia, A. Persistence of ADHD into Adulthood and Associated Factors: A Prospective Study. Psiquiatr. Biológica 2025, 32, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komijani, S.; Ghosal, D.; Singh, M.K.; Schweitzer, J.B.; Mukherjee, P. A Novel Framework to Predict ADHD Symptoms Using Irritability in Adolescents and Young Adults with and without ADHD. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 1467486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riglin, L.; Leppert, B.; Dardani, C.; Thapar, A.; Rice, F.; O’Donovan, M.; Smith, G.; Stergiakouli, E.; Tilling, K.; Thapar, A. ADHD and Depression: Investigating a Causal Explanation. Psychol. Med. 2020, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chang, J.J.; Xian, H.; Arnold, L.D. Factors Associated with Mental Health Service Use Among Children with ADHD from Adolescence to Early Adulthood. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2025, 52, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.A.; Antshel, K.M. Bullying and Depression in Youth with ADHD: A Systematic Review. Child Youth Care Forum 2021, 50, 379–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, K.; Hjern, A. Bullying and Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder in 10-Year-Olds in a Swedish Community. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braams, B.R.; van Rijn, R.; Leijser, T.; Dekkers, T.J. The Upside of ADHD-Related Risk-Taking: Adolescents with ADHD Report a Higher Likelihood of Engaging in Prosocial Risk-Taking Behavior than Typically Developing Adolescents. J. Atten. Disord. 2025, 10870547251321882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuba Bustinza, C.; Adams, R.E.; Claussen, A.H.; Vitucci, D.; Danielson, M.L.; Holbrook, J.R.; Froehlich, T.E. Factors Associated with Bullying Victimization and Bullying Perpetration in Children and Adolescents with ADHD: 2016 to 2017 National Survey of Children’s Health. J. Atten. Disord. 2022, 26, 1535–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuade, J.D.; Breslend, N.L.; Groff, D. Experiences of Physical and Relational Victimization in Children with ADHD: The Role of Social Problems and Aggression. Aggress. Behav. 2018, 44, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.L.; Zych, I.; Ribeaud, D.; Eisner, M. Developmental Relations Between ADHD Symptoms and Bullying Perpetration and Victimization in Adolescence. Aggress. Behav. 2021, 47, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, R.; Blake, J.; Chen, S. Bully Victimization Among Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Longitudinal Examination of Behavioral Phenotypes. J Emot Behav Disord 2018, 28, 106342661881472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinden, M.; Jansen, P.W.; Veenstra, R.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; Verhulst, F.C.; Shaw, P.; Tiemeier, H. Preschool Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity and Oppositional Defiant Problems as Antecedents of School Bullying. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glans, M.; Bejerot, S. ADHD Symptoms Are Associated with Bully Victimization in Non-Clinical Populations Too. Eur. Psychiatry 2024, 67, S453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullies on the Playground: The Role of Victimization. In Children on Playgrounds: Research Perspectives and Applications; SUNY Series, Children’s Play in Society; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 85–128. ISBN 9780791414675/9780791414682. [Google Scholar]

- Ghardallou, M.; Mtiraoui, A.; Ennamouchi, D.; Amara, A.; Gara, A.; Dardouri, M.; Mtiraoui, A. Bullying Victimization among Adolescents: Prevalence, Associated Factors and Correlation with Mental Health Outcomes. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Understanding School Bullying: Its Nature & Prevention Strategies; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781847879059. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Donoghue, C.; Pascoe, C.J. A Sociology of Bullying: Placing Youth Aggression in Social Context. Sociol. Compass 2023, 17, e13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C.; Lagerspetz, K.; Björkqvist, K.; Österman, K.; Kaukiainen, A. Bullying as a Group Process: Participant Roles and Their Relations to Social Status Within the Group. Aggress. Behav. 1996, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grama, D.I.; Georgescu, R.D.; Coşa, I.M.; Dobrean, A. Parental Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Bullying Victimization in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 27, 627–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menesini, E.; Salmivalli, C. Bullying in Schools: The State of Knowledge and Effective Interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogen, I.B.; Båtevik, F.O.; Krumsvik, R.J.; Høydal, K.L. Weight-Based Victimization and Physical Activity among Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity: A Scoping Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 732737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.T.; Bishop, M.D.; Saba, V.C.; James, I.; Ioverno, S. Promoting School Safety for LGBTQ and All Students. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2021, 8, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R.; Bjereld, Y.; Augustine, L. Developmental Relations Between Peer Victimization, Emotional Symptoms, and Disability/Chronic Condition in Adolescence: Are Within- or Between-Person Factors Driving Development? J. Youth Adolesc. 2024, 53, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnfjord, V.; Hagquist, C. Students’ Perception of Efforts by School Staff to Counteract Bullying and Its Association with Students’ Psychosomatic Problems: An Ecological Approach. Trends Psychol. 2024, 32, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gong, H.; Sun, W.; Ma, P.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y. The Health Context Paradox in the Relationship between Victimization, Classroom Bullying Attitudes, and Adolescent Depression: An Analysis Based on the HLM Model. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 354, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, S.; Rossmann, P. Peer Integration, Teacher-Student Relationships and the Associations with Depressive Symptoms in Secondary School Students with and without Special Needs. Educ. Stud. 2020, 46, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S.H.; DeRosier, M.E. Teacher Preference, Peer Rejection, and Student Aggression: A Prospective Study of Transactional Influence and Independent Contributions to Emotional Adjustment and Grades. J. Sch. Psychol. 2008, 46, 661–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.J.; Ayllón, E.; Tomás, I. Coping Strategies against Peer Victimization: Differences According to Gender, Grade, Victimization Status and Perceived Classroom Social Climate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elledge, L.C.; Elledge, A.R.; Newgent, R.A.; Cavell, T.A. Social Risk and Peer Victimization in Elementary School Children: The Protective Role of Teacher-Student Relationships. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2016, 44, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demol, K.; Verschueren, K.; Ten Bokkel, I.M.; van Gils, F.E.; Colpin, H. Trajectory Classes of Relational and Physical Bullying Victimization: Links with Peer and Teacher-Student Relationships and Social-Emotional Outcomes. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 1354–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, S.; Schneider, B.; Lee, M.; Maisonneuve, M.-F.; Kuehn, S.; Robaey, P. How Do Children with ADHD (Mis)Manage Their Real-Life Dyadic Friendships? A Multi-Method Investigation. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2011, 39, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spender, K.; Chen, Y.W.R.; Wilkes-Gillan, S.; Parsons, L.; Cantrill, A.; Simon, M.; Cordier, R. The Friendships of Children and Youth with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, S.; Lambert, M.; Guiet, J.; Brendgen, M.; Bakeman, R.; Mikami, A.Y. Peer Contagion Dynamics in the Friendships of Children with ADHD. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 63, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaert, N.; Morreale, K.; Tseng, W. Peer Functioning Difficulties May Exacerbate Symptoms of Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Irritability over Time: A Temporal Network Analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2023, 65, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Rodríguez, L.; Redín, C.I.; Abaitua, C.R. Teacher–Student Attachment Relationship, Variables Associated, and Measurement: A Systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2023, 38, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Retrospect and Prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. Early Teacher–Child Relationships and the Trajectory of Children’s School Outcomes through Eighth Grade. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabol, T.J.; Pianta, R.C. Recent Trends in Research on Teacher–Child Relationships. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2012, 14, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bergin, C.; Olsen, A.A. Positive Teacher–Student Relationships May Lead to Better Teaching. Learn. Instr. 2022, 80, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, G.R.S.; da Silva, G.A.P.; Padilha, B.M.; de Carvalho Lima, M. Determining Factors of Child Linear Growth from the Viewpoint of Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory. J. Pediatr. 2023, 99, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780470147658. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.N.; Im, M.H. Teacher–Student Relationship and Peer Disliking and Liking across Grades 1–4. Child. Dev. 2016, 87, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchiatti, M.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Ferrer, A.; Longobardi, C.; Gastaldi, F.G.M. Bullying in Students Who Stutter: The Role of the Quality of the Student–Teacher Relationship and Student’s Social Status in the Peer Group. J. Sch. Violence 2020, 20, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchiatti, M.; Ferrer, A.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Longobardi, C. School Adjustments in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Peer Relationships, the Quality of the Student–Teacher Relationship, and Children’s Academic and Behavioral Competencies. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 38, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchiatti, M.; Ferrer, A.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Longobardi, C. Student–Teacher Relationship Quality in Students with Learning Disabilities and Special Educational Needs. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2022, 28, 2887–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrokoukou, S.; Longobardi, C.; Fabris, M.A.; Lin, S. Subjective Socioeconomic Status and Life Satisfaction among High School Students: The Role of Teacher-Student Relationships. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 28, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Strohmeier, D.; Kollerová, L. Teachers Can Make a Difference in Bullying: Effects of Teacher Interventions on Students’ Adoption of Bully, Victim, Bully-Victim or Defender Roles across Time. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 2312–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, J.; Krause, A.; Rogers, M.A. The Student-Teacher Relationship and ADHD Symptomatology: A Meta-Analysis. J. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 99, 101217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendarski, N.; Haebich, K.; Bhide, S.; Quek, J.; Nicholson, J.M.; Jacobs, K.E.; Efron, D.; Sciberras, E. Student–Teacher Relationship Quality in Children with and without ADHD: A Cross-Sectional Community Based Study. Early Child Res. Q. 2020, 51, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iines, R.P.; Sami, J.M.; Vesa, M.N.; Hannu, K.S. ADHD Symptoms and Maladaptive Achievement Strategies: The Reciprocal Prediction of Academic Performance Beyond the Transition to Middle School. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2023, 28, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.J.; Bristow, S.J.; Kovshoff, H.; Cortese, S.; Kreppner, J. The effects of ADHD teacher training programs on teachers and pupils: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Atten. Disord. 2022, 26, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.K.; Metwaly, N.A.; Elbeh, K.; Galal, M.S.; Shaaban, I. Prevalence of school bullying and its relationship with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: A cross-sectional study. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2022, 58, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, A.Y. The Importance of Friendship for Youth with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 13, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.; Mak, M. Peer Victimization in Children with ADHD. Psychol. Sch. 2009, 46, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F.A. A Developmental Psychopathology Perspective on Adolescence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C. Enhancing Relationships Between Children and Teachers; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Bader, S.; Jones, T.V. Statistical Mediation Analysis Using the Sobel Test and Hayes SPSS PROCESS Macro. Int. J. Quant. Qual. Res. Methods 2021, 9, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eurydice. Organisation of General Upper Secondary Education: Italy. 2024. Available online: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/eurypedia/italy/organisation-general-upper-secondary-education (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Lindner, K.T.; Schwab, S.; Emara, M.; Avramidis, E. Do Teachers Favor the Inclusion of All Students? A Systematic Review of Primary Schoolteachers’ Attitudes towards Inclusive Education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2023, 38, 766–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, F.; Morganti, A.; Signorelli, A. The Italian Leadership on Inclusive Education: Myth or Reality? Sci. Insights Educ. Front. 2021, 9, 1241–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iudici, A.; Tassinari Rogalin, M.; Turchi, G. Health Service and School: New Interactions. Comparison between the Italian System and the Swedish System on the Diagnostic Process of Pupils. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 25, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Mento, C.; Gangemi, A.; Picciotto, G. ADHD Symptoms Increase Perception of Classroom Entropy and Impact Teacher Stress Levels. Children 2023, 10, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M.C.; Di Maggio, I.; Valbusa, I.; Santilli, S.; Nota, L. Teachers’ Attitudes towards Students with Disabilities: The Role of the Type of Information Provided in the Students’ Profiles of Children with Disabilities. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 37, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, R. Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument: A Theoretical and Empirical Basis for the Measurement of Participant Roles in Bullying and Victimisation of Adolescence: An Interim Test Manual and a Research Monograph: A Test Manual; Publication Unit, Self-Concept Enhancement and Learning Facilitation (SELF) Research Centre, University of Western Sydney: Penrith, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq, S.; Batool, S. Bullying, Victimization, and Rejection Sensitivity in Adolescents: Mediating Role of Self-Regulation. J. Postgrad. Med. Inst. 2021, 35, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Reeve, J.; Guo, J.; Pekrun, R.; Parada, R.H.; Parker, P.D.; Cheon, S.H. Overcoming Limitations in Peer-Victimization Research That Impede Successful Intervention: Challenges and New Directions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 18, 812–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomen, H.M.Y.; Jellesma, F.C. Can Closeness, Conflict, and Dependency Be Used to Characterize Students’ Perceptions of the Affective Relationship with Their Teacher? Testing a New Child Measure in Middle Childhood. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 85, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C.; Gastaldi, F.G.M.; Fabris, M.A.; Settanni, M. Measuring and Validating the Student Perception of Affective Relationship with Teacher Scale (SPARTS) in Italian Pre-Adolescents. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. 2023, 31, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.L. Who Shall Survive? Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company: Washington, DC, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Coie, J.D.; Dodge, K.A.; Coppotelli, H. Dimensions and Types of Social Status: A Cross-Age Perspective. Dev. Psychol. 1982, 18, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geukens, F.; Maes, M.; Cillessen, A.H.; Colpin, H.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Verschueren, K.; Goossens, L. Spotting Loneliness at School: Associations between Self-Reports and Teacher and Peer Nominations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.; Muthén, B. Mplus (Version 8) [Computer Software]; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pagán, A.F.; Ricker, B.T.; Cooley, J.L.; Cummings, C.; Sanchez, C.R. ADHD Symptoms and Sleep Problems during Middle Childhood: The Indirect Effect of Peer Victimization. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chang, H. Developmental Trajectory of Inattention and Its Association with Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence: Peer Relationships as a Mediator. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 736840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Siraj-Ud-Doulah, M. An Alternative Measures of Moments Skewness Kurtosis and JB Test of Normality. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 2021, 20, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hills-dale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lovakov, A.; Agadullina, E.R. Empirically Derived Guidelines for Effect Size Interpretation in Social Psychology. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, A.; Zenker, F. Cohen’s Convention, the Seriousness of Errors, and the Body of Knowledge in Behavioral Science. Synthese 2024, 204, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J.S. Multifaceted conceptions of fit in structural equation models. In Testing Structural Equation Model; Bollen, K.A., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 10–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, B.M. The Ethical Use of Fit Indices in Structural Equation Modeling: Recommendations for Psychologists. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 783226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, D.; Wolf, M.G. Dynamic Fit Index Cutoffs for One-Factor Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 54, 1809–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Boda, Z.; Lorenz, G. Social comparison effects on academic self-concepts—Which peers matter most? Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 1541–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwier, D.; Geven, S. Knowing me, knowing you: Socio-economic status and (segregation in) peer and parental networks in primary school. Soc. Netw. 2023, 74, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class ID | Grade | Gender | Age | Socioeconomic Status | Years Since ADHD Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C01 | Primary 4 | Male | 9 | Medium | 1 |

| C02 | Primary 4 | Female | 9 | Low | 1 |

| C03 | Primary 5 | Male | 10 | Medium | 2 |

| C04 | Primary 5 | Male | 10 | High | 2 |

| C05 | Primary 6 | Male | 11 | Low | 2 |

| C06 | Primary 6 | Male | 11 | Medium | 3 |

| C07 | Secondary 1 | Male | 12 | High | 3 |

| C08 | Secondary 1 | Female | 12 | Medium | 3 |

| C09 | Secondary 2 | Male | 13 | Low | 4 |

| C10 | Secondary 2 | Male | 13 | Medium | 4 |

| C11 | Secondary 3 | Male | 14 | Medium | 5 |

| C12 | Secondary 3 | Female | 14 | High | 5 |

| C13 | Secondary 3 | Male | 14 | Low | 5 |

| C14 | Primary 4 | Male | 9 | Low | 1 |

| C15 | Primary 5 | Female | 10 | Medium | 2 |

| C16 | Primary 6 | Male | 11 | High | 2 |

| C17 | Secondary 1 | Male | 12 | Medium | 3 |

| C18 | Secondary 1 | Male | 12 | Low | 3 |

| C19 | Secondary 2 | Female | 13 | Medium | 4 |

| C20 | Secondary 2 | Male | 13 | High | 4 |

| C21 | Secondary 3 | Male | 14 | Medium | 5 |

| C22 | Secondary 3 | Female | 14 | Medium | 5 |

| C23 | Primary 5 | Male | 10 | Low | 2 |

| C24 | Primary 6 | Female | 11 | High | 2 |

| C25 | Secondary 1 | Male | 12 | Medium | 3 |

| C26 | Secondary 2 | Male | 13 | Low | 4 |

| C27 | Secondary 3 | Male | 15 | High | 5 |

| Teacher ID | Class IDs | Gender | Age | Years of Teaching | Socioeconomic Info | Type of Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T01 | C01, C02 | Female | 45 | 15 | Medium | Permanent |

| T02 | C03 | Female | 42 | 14 | Medium | Permanent |

| T03 | C04 | Male | 48 | 20 | High | Permanent |

| T04 | C05 | Female | 40 | 10 | Low | Permanent |

| T05 | C06 | Female | 44 | 13 | Medium | Temporary |

| T06 | C07 | Female | 47 | 16 | High | Permanent |

| T07 | C08 | Female | 50 | 22 | Medium | Permanent |

| T08 | C09 | Female | 46 | 17 | Low | Permanent |

| T09 | C10 | Male | 36 | 4 | Medium | Temporary |

| T10 | C11 | Female | 43 | 14 | Medium | Permanent |

| T11 | C12 | Female | 49 | 18 | High | Permanent |

| T12 | C13 | Female | 53 | 25 | Low | Permanent |

| T13 | C14 | Female | 38 | 8 | Low | Temporary |

| T14 | C15 | Female | 44 | 11 | Medium | Permanent |

| T15 | C16 | Male | 41 | 10 | High | Permanent |

| T16 | C17 | Female | 46 | 13 | Medium | Permanent |

| T17 | C18 | Female | 39 | 6 | Low | Temporary |

| T18 | C19, C20 | Female | 48 | 19 | Medium | Permanent |

| T19 | C21, C22, C23, C24, C25, C26, C27 | Female | 51 | 30 | Mixed | Permanent |

| Total Sample | Students with ADHD | Students with TD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t | p | Cohen’s d (95% CI) | |

| Closeness (SPARTS) | 8–40 | 28.13 (7.91) | 29.78 (8.68) | 27.71 (7.69) | 1.22 | 0.225 | 0.26 (−0.16, 0.69) |

| Conflict (SPARTS) | 10–44 | 18.36 (6.91) | 21.04 (6.80) | 17.69 (6.80) | 2.29 | 0.024 | 0.49 (0.07, 0.92) |

| Negative Expectations (SPARTS) | 7–28 | 15.36 (4.92) | 15.94 (4.67) | 15.21 (4.99) | 0.69 | 0.490 | 0.15 (−0.27, 0.57) |

| Verbal Victimization (APRI) | 6–36 | 11.72 (6.57) | 13.64 (7.21) | 11.24 (6.34) | 1.71 | 0.090 | 0.37 (−0.06, 0.79) |

| Physical Victimization (APRI) | 6–32 | 9.41 (5.59) | 10.57 (6.66) | 9.11 (5.29) | 1.21 | 0.228 | 0.26 (−0.16, 0.68) |

| Social Victimization (APRI) | 6–36 | 10.15 (5.83) | 12.20 (6.71) | 9.63 (5.50) | 2.08 | 0.040 | 0.45 (0.02, 0.87) |

| Verbal Perpetration (APRI) | 6–29 | 9.30 (3.82) | 9.78 (3.95) | 9.18 (3.80) | 0.73 | 0.466 | 0.16 (−0.26, 0.58) |

| Physical Perpetration (APRI) | 6–25 | 8.24 (3.49) | 8.61 (3.98) | 8.15 (3.68) | 0.62 | 0.534 | 0.13 (−0.29, 0.56) |

| Social Perpetration (APRI) | 6–28 | 10.25 (3.76) | 9.96 (4.05) | 10.32 (3.70) | −0.44 | 0.664 | −0.09 (−0.52, 0.33) |

| Social Preference (Z scores) | -- | −0.27 (1.79) | −1.75 (1.93) | 0.10 (1.55) | −5.27 | <0.001 | −1.13 (−1.58, −0.69) |

| Social Impact (Z scores) | -- | 0.17 (0.97) | 0.58 (1.17) | 0.07 (0.90) | 2.12 | 0.045 | 0.53 (0.11, 0.96) |

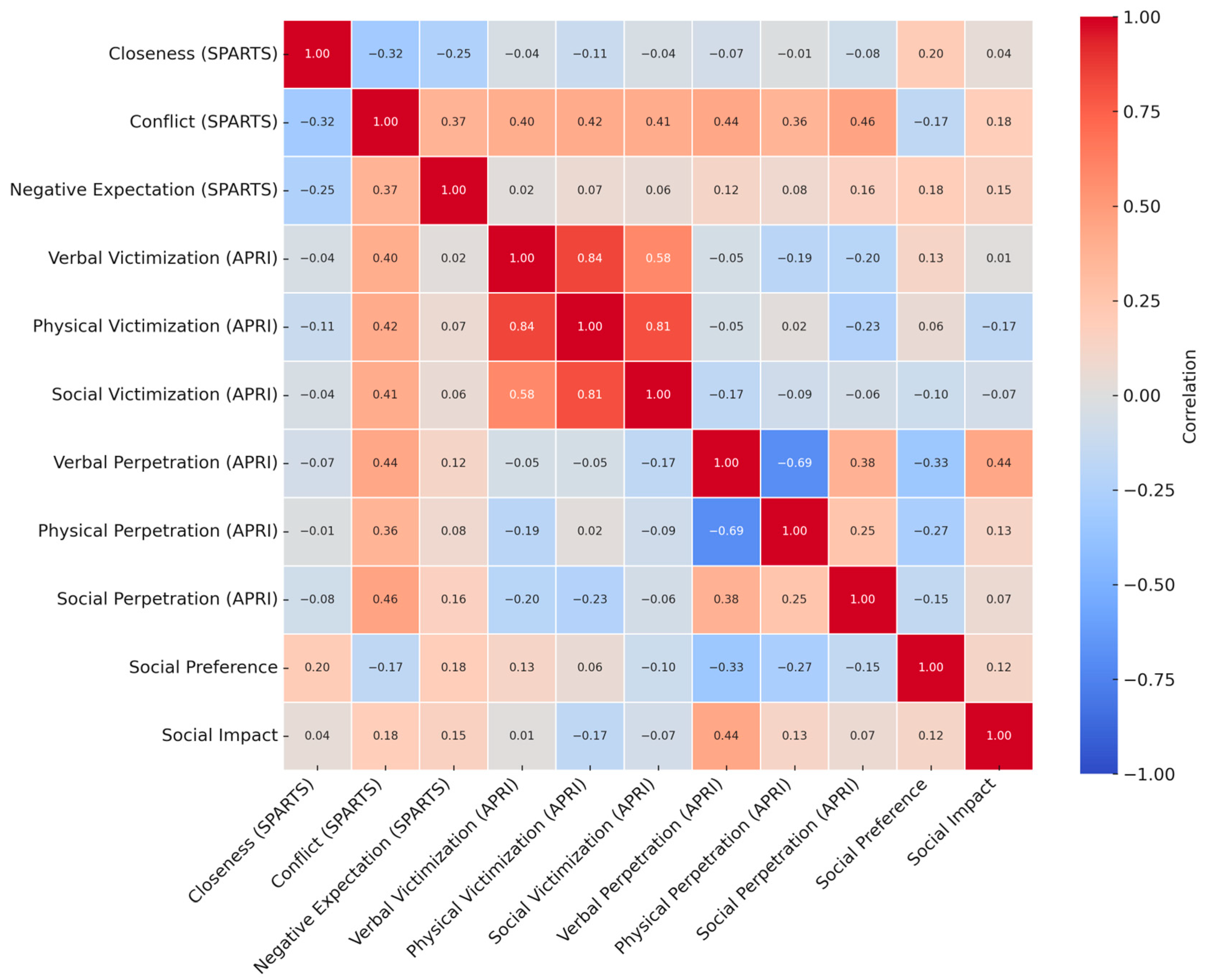

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Closeness (SPARTS) | – | −0.32 | −0.05 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.14 | −0.39 * | −0.50 ** | −0.12 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| 2. Conflict (SPARTS) | −0.32 ** | – | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.51 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.32 | −0.06 | 0.26 |

| 3. Negative Expectation (SPARTS) | −0.25 ** | 0.37 *** | – | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| 4. Verbal Victimization (APRI) | −0.04 | 0.40 *** | 0.02 | – | 0.84 *** | 0.58 ** | −0.05 | −0.19 | −0.20 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| 5. Physical Victimization (APRI) | −0.11 | 0.42 *** | 0.07 | 0.82 *** | – | 0.68 *** | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.23 | 0.06 | −0.17 |

| 6. Social Victimization (APRI) | −0.04 | 0.41 *** | 0.06 | 0.86 *** | 0.81 *** | – | −0.17 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.07 |

| 7. Verbal Perpetration (APRI) | −0.07 | 0.44 *** | 0.12 | 0.42 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.43 *** | – | 0.69 *** | 0.38 * | −0.33 | 0.44 * |

| 8. Physical Perpetration (APRI) | −0.01 | 0.36 *** | 0.08 | 0.43 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.73 *** | – | 0.25 | −0.27 | 0.13 |

| 9. Social Perpetration (APRI) | −0.08 | 0.46 *** | 0.16 | 0.44 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.73 *** | 0.62 *** | – | 0.15 | 0.07 |

| 10. Social Preference | 0.20 * | −0.17 | 0.18 | −0.23 * | −0.20 * | −0.23 * | −0.24 * | −0.18 | −0.19 * | – | −0.54 ** |

| 11. Social Impact | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.20 * | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.26 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.22 * | 0.12 | – |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Closeness (SPARTS) | – | ||||

| 2. Conflict (SPARTS) | −0.320 ** | – | |||

| 3. Negative Expectations (SPARTS) | −0.209 ** | 0.346 *** | – | ||

| 4. Social Preference | 0.205 * | −0.145 | 0.144 | – | |

| 5. Social Impact | 0.032 | 0.200 ** | 0.149 | −0.068 | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mastrokoukou, S.; Berchiatti, M.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Galiana, L.; Longobardi, C. Bullying in Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Analyzing Students’ Social Status and Student–Teacher Relationship Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060878

Mastrokoukou S, Berchiatti M, Badenes-Ribera L, Galiana L, Longobardi C. Bullying in Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Analyzing Students’ Social Status and Student–Teacher Relationship Quality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060878

Chicago/Turabian StyleMastrokoukou, Sofia, Martina Berchiatti, Laura Badenes-Ribera, Laura Galiana, and Claudio Longobardi. 2025. "Bullying in Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Analyzing Students’ Social Status and Student–Teacher Relationship Quality" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060878

APA StyleMastrokoukou, S., Berchiatti, M., Badenes-Ribera, L., Galiana, L., & Longobardi, C. (2025). Bullying in Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Analyzing Students’ Social Status and Student–Teacher Relationship Quality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060878