A Framework for Developing Awareness Interventions: A Case of Mobile Bullying

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mobile Bullying

1.2. The Current Study

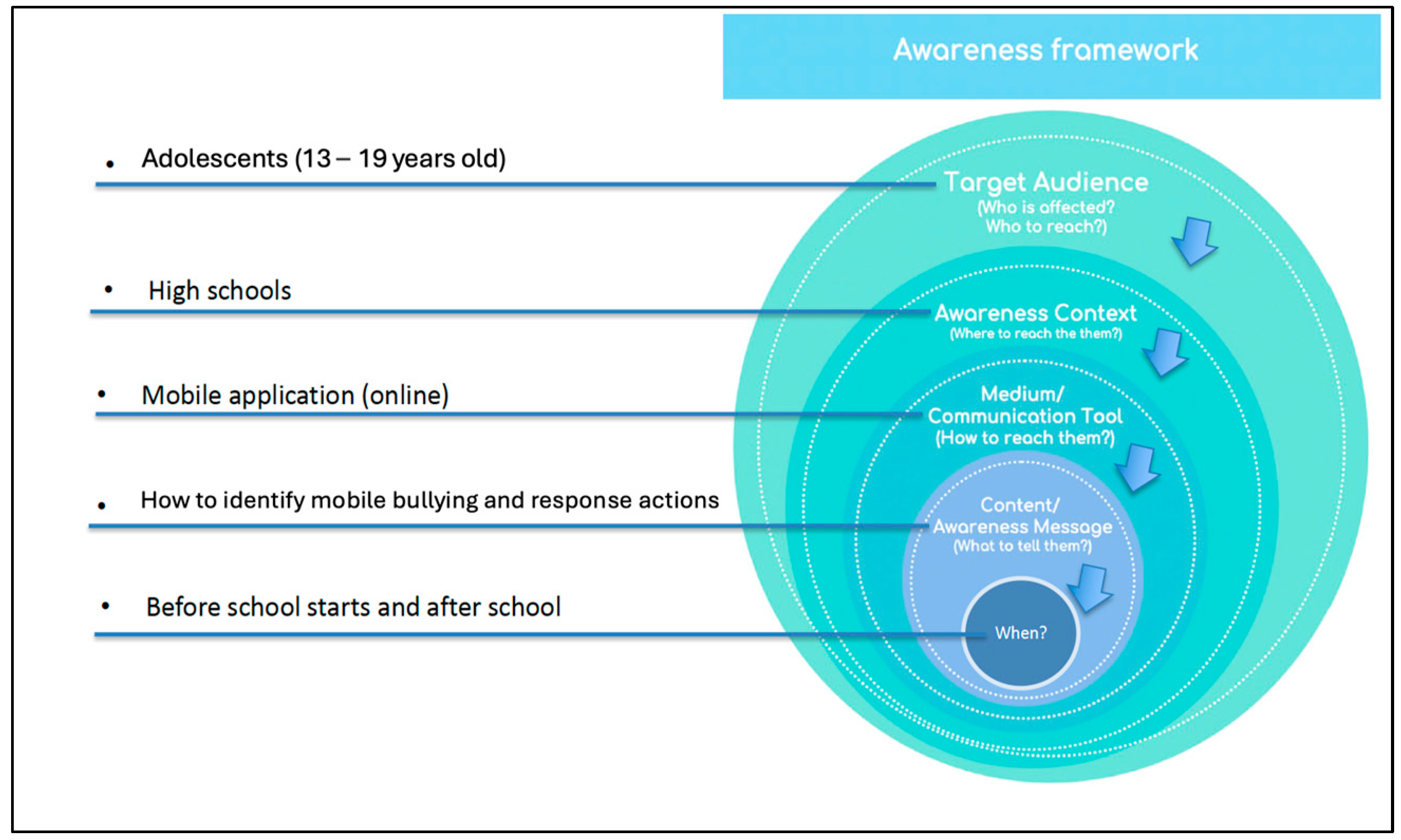

- Who is the target audience—Who is affected?

- What is the awareness context—Where can the audience be reached?

- What is the communication medium/tool for awareness—What are the available means to reach the audience?

- What is the awareness content or message—What should be communicated in the awareness campaign?

- What are the intervention timelines—When should the target audience be reached? When is the best time to reach the target audience through the chosen medium?

- Product: In the context of raising mobile bullying awareness, the product would be an awareness campaign or initiative. This includes identifying the specific message that needs to be communicated, the target audience, and the desired outcome. The product should be designed to resonate with the target audience and address the specific issue of mobile bullying [41]. The product refers to the thing which the marketing consumer is being informed about. In the context of raising awareness, the product would be represented by the awareness message about a topic or concept. The product (awareness topics presented to participants) could affect mobile bullying awareness in the participant population. And thus, the contents of the awareness message may affect the levels of awareness amongst adolescents. Therefore, the awareness message about mobile bullying can help raise awareness.

- Place: The place element of the marketing strategy mix refers to the distribution channels used to reach the target audience. For mobile bullying awareness interventions, this may include social media platforms, mobile apps, and other online channels where the target audience is most active [40]. The place, in the case of mobile bullying awareness, could represent the awareness context, i.e., the place where the target population can be reached. For this study, the context is the school environment. Thus, the social environment (home environment) may affect the awareness in the participant population.

- Promotion: Promotion includes the communication channels used to promote the mobile bullying awareness campaign. This includes social media advertising, email marketing, public relations, and other forms of promotion that are designed to generate awareness and engage the target audience [42]. The promotion aspect of an awareness intervention is the platform or medium where the awareness message is made available. The platform or medium of delivery can help raise awareness. Therefore, the medium or tool of delivery (i.e., awareness platform or channel as the intervention environment) may affect the awareness levels in the participant population [37].

- Price: The price element of the marketing strategy mix refers to the cost associated with the awareness campaign. This may include the cost of producing and distributing promotional materials, as well as any costs associated with running online ads or social media campaigns [41,42]. The price pertains to the cost of raising awareness. Practitioners may incur costs in providing awareness content. How much they are willing to spend on the intervention may affect the quality of the awareness intervention and subsequently affect the intervention’s effectiveness. Therefore, the price or costs may affect awareness levels among adolescents. Since the intervention is at no cost to the school and learners, the intervention development costs may affect the distribution and available features (tool complexity and reach) and the extent to which the tool becomes available to raise awareness.

- People: The people element of the marketing strategy mix refers to the people who are responsible for creating and executing the awareness campaign. This includes the project team, volunteers, and any external partners or stakeholders who are involved in the initiative [40]. The people represent the target audience for an awareness intervention. The participation rate of the people affects the number of people exposed to the intervention and thus affects the awareness levels of the population.

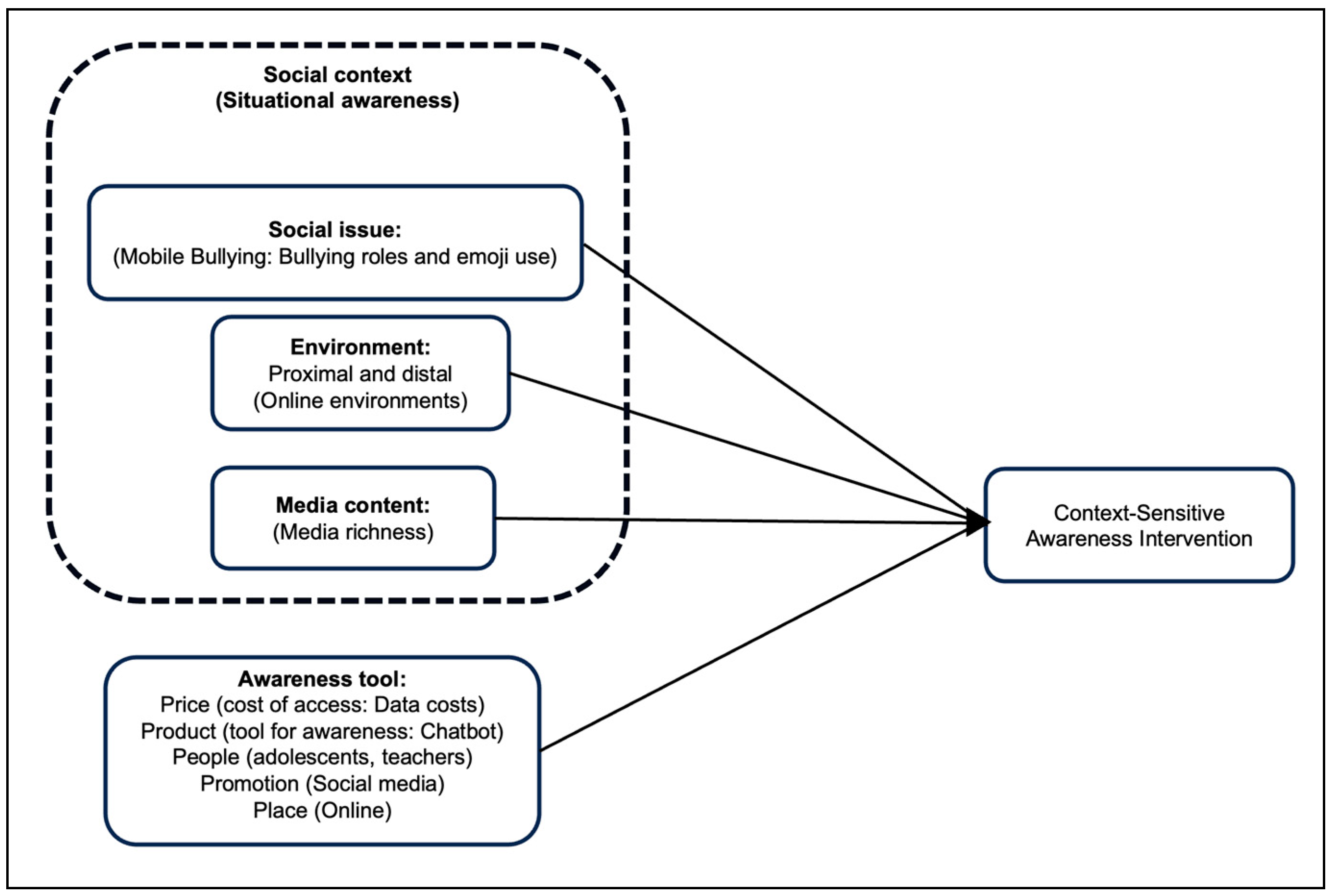

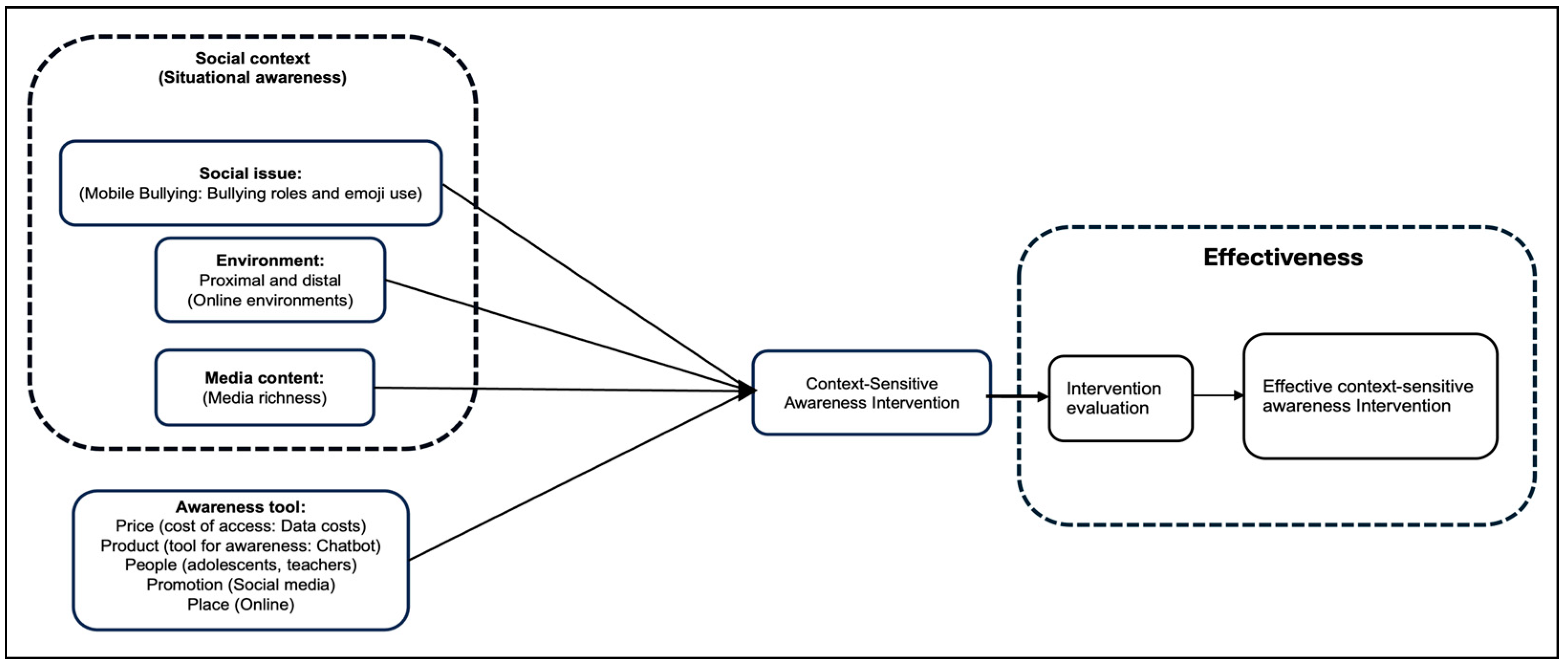

- For the social issue: The social issue should be informed by the related social theory on how to effect awareness for that issue. In the context of mobile bullying, there are roles associated with those involved or affected [45,46]. The roles that emerge as a result of the social issue in question, i.e., mobile bullying, need to be considered when raising awareness, as per role theory and situational awareness theory [30]. Thus, role theory can shed some light on understanding the social roles that affect mobile bullying awareness in the participants’ social context.

- Regarding the environment as an aspect of the framework: The proximal and distal environments have an impact on raising awareness of a social issue [30,47]. Thus, for this study, immediate environments (school, home, online) and distal environments (government departments, legislations) have to be considered when developing interventions for communicating awareness. Distal environments regulate the educational content that is suitable for consumption by school-aged children [48].

- Regarding media content: The media richness theory informs the decision to consider the most appropriate media to communicate a message based on the needs of the audience [49]. Thus, the media richness theory provides a guide on what researchers can consider as an appropriate communication medium to use for communicating a message, given their audience. In recent years, instant messaging has become the most commonly used form of communication for daily use. As such, it is even embedded in corporate communication channels [50,51].

- For the awareness tool: On the left-hand side of the conceptual framework, the awareness tool and the messages it delivers are informed by the marketing mix which encompasses the five Ps of marketing (price, product, people, promotion, and place) to ensure that the awareness message is impactful to the intended audience [41,42].

- Context-sensitive awareness intervention: The elements of the framework that appear on the left-hand side are the independent variables, which influence the dependent variable that appears on the right-hand side of the framework in the diagram in Figure 2. The context-sensitive awareness intervention is informed by the social context, Where the issue of social concern is experience, as well as the proposed suitable tool for raising awareness in the target population during the process of intervening [41]. As such, an awareness intervention that is developed by following the proposed intervention conceptual framework should be suitable for the issue of interest and the social context. Thus, the intervention itself is dependent on the context and selected method of raising awareness, referred to in the model as the awareness tool [30].

2. Materials and Methods

- 6.

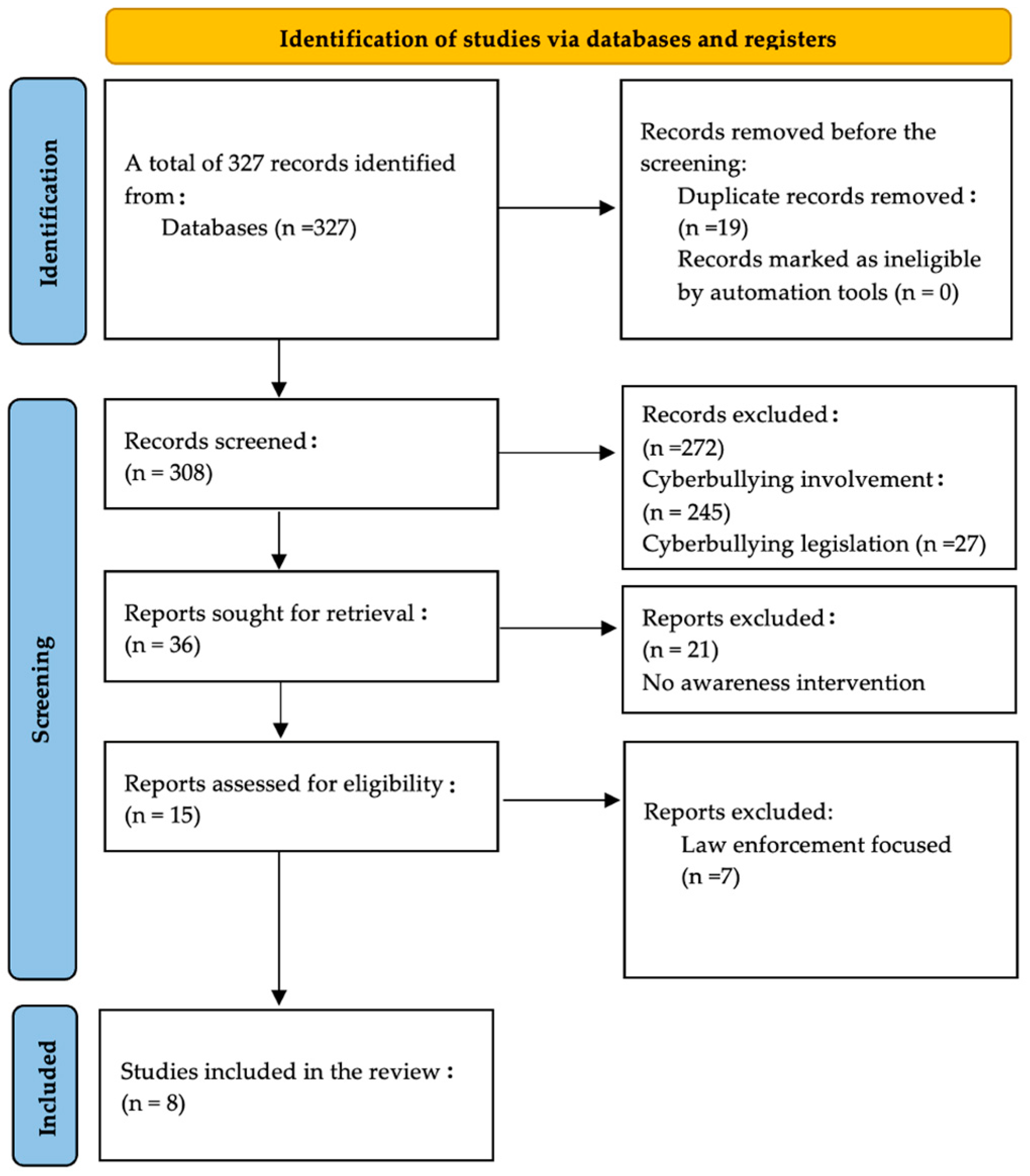

- Definition of the search protocol: The sources for the literature were online academic databases. The search terms for the study were (“*awareness interventions”); (“*bullying awareness*”); (“cyberbullying intervention*”); (“awareness” or “aware*”); and (“*bullying*” AND “*intervention*”).

- 7.

- Search and identification of academic papers: A search was conducted on academic databases (Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus) for publications using the keywords defined in the search protocol. The period of the review was 15 years and included publications between the years 2009 and 2024. A total of 327 academic articles resulted from the search. During this period, there was a rapid increase in the social use of digital devices. Moreover, there was a rise in cyberbullying and mobile bullying.

- 8.

- Paper selection and screening: From the search results of 327 publication records, 19 duplicate entries were removed and 308 research papers were screened. From the screening process, a total of 272 records were excluded based on the exclusion criteria, i.e., 245 entries had a focus on bullying involvement and 27 on cyberbullying legislation instead of intervention development.

- 9.

- Review and analysis of the selected papers: After the screening process, 36 entries remained, of which 21 were excluded as they did not involve any awareness interventions. Thereafter, 15 publications remained, of which 7 were excluded on the basis that they focused on law enforcement. A total of 8 papers focused on the development of awareness interventions and were analyzed for this study (see Table 1).

- 10.

- Result presentation and write-up: A review of the applied theories was conducted to develop an instrumental model as well as a conceptual framework in order to guide the development of an awareness intervention.

| Study Location | Objective | Methodology | Intervention | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Western Australia [12] | To review existing whole-school interventions and inform cyberbullying intervention strategies. | Meta-analysis | None. Review of existing interventions. | In school-based anti-bullying programs, whole-school interventions are the most effective. Bullying can be prevented and managed through non-stigmatization. Six broad whole-school indicators were included. |

| 2. Campania, Italy [13] | To evaluate the Tabby Improved Prevention and Intervention Program (TIPIP) and its long-term effectiveness. | Experiment | Tabby Improved Prevention and Intervention Program for cyberbullying and cybervictimization. | The study found that the TIPIP intervention was ineffective or had limited effectiveness in the long term, despite significant effectiveness in the short-term post implementation. |

| 3. Perlis State, Malaysia [15] | To review the use of a multimedia application (CyBA) to increase cyber-bullying knowledge and to evaluate the effectiveness of the CyBA intervention. | Quasi-experimental research design | Multimedia application for cyber-bullying awareness (CyBA). | The study results indicate that perceived knowledge and awareness increased after participant interaction with the intervention. Thus, they concluded that the CyBA intervention had a positive impact among adolescents. |

| 4. South Africa [17] | To descriptively present the development and implementation process for a mobile application as an intervention to monitor and report mobile victimization in high schools. | Design science research | Mobile application for monitoring and reporting victimization, based on the Mobile Victimization Typology (MVT). | The design science process of developing the digital application was documented and explained. The development followed the Mobile Victimization Typology (MVT) structure to improve the process of identifying, describing, explaining, and comparing mobile victimization. |

| 5. United Kingdom [22] | To determine the effectiveness of existing school-based anti-bullying programs in reducing school-bullying behaviors. | Meta-analysis | None. Review of existing interventions. | The study found that school-based antibullying interventions were effective in reducing bullying perpetration by 18–19%, and victimization by about 15–16%. |

| 6. Regional: Europe, North America, and Scandinavia [23] | To review the effectiveness of of school-based bullying prevention programs. | Meta-analysis | None. Review of existing interventions. | The NoTrap! Program had significant effectiveness in reducing bullying victimization. The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program had the largest effects regarding bullying perpetration outcomes. |

| 7. Europe [24] | To investigate the design and implementation insights of two European projects aimed at supporting schools with the training of resilience as a protective factor to prevent (cyber)bullying and with the deployment of innovative digital interventions to detect and prevent this phenomenon early. | Co-design | UPRIGHT program and CREEP Virtual Coach. CREEP Semantic Technology is a detection tool for cyber threats in schools. | The main challenges and insights collected during the design and implementation of both interventions are discussed to inform future research and practice. Conclusion: The feasibility and acceptance of prevention programs are key to reducing the risk of (cyber)bullying and improving the psychological well-being of young adolescents. |

| 8. [38] | To systematically review the literature, the authors identified public-directed interventions to promote awareness of antibiotics prescriptions. | Systematic review | Antibiotic awareness. | Many interventions were multifaceted and distributed educational materials within the community as well as clinical sites. Most studies that measured antibiotics prescriptions reported success. |

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Attaran, M.; Attaran, S.; Kirkland, D. The Need for Digital Workplace. Int. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2019, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K. The Human Resources Revolution: Is It a Productivity Driver? Innov. Policy Econ. 2004, 4, 69–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crafts, N. Explaining the First Industrial Revolution: Two Views. Eur. Rev. Econ. Hist. 2011, 1, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, H. The Second Industrial Revolution Has Brought Modern Social and Economic Developments. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Atkeson, A.; Kehoe, P.J. The Transition to a New Economy After the Second Industrial Revolution. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2001, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyagadza, B.; Pashapa, R.; Chare, A.; Mazuruse, G.; Hove, P.K. Digital technologies, Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) & Global Value Chains (GVCs) nexus with emerging economies’ future industrial innovation dynamics. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2014654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Shah, N.; Chen, L.; Diallo, N.; Gao, Z.; Lu, Y.; Shi, W. Enabling the Sharing Economy: Privacy Respecting Contract Based on Public Blockchain. In Proceedings of the ASIA CCS ′17: ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2 April 2017; pp. 15–21. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3055527 (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Buthelezi, M.; Kyobe, M. Factors Affecting the lack of Awareness: Towards a Framework for Raising Mobile Bullying Awareness. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical, Computer, and Energy Technologies, ICECET 2021, Cape Town, South Africa, 9–10 December 2021; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berne, S.; Frisén, A.; Oskarsson, J. High school students’ suggestions for supporting younger pupils counteract cyberbullying. Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penprase, B.E. The fourth industrial revolution and higher education. In Higher Education in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2018; pp. 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P.; McCord, A. A developmental approach to cyberbullying: Prevalence and protective factors. Aggress. Violent. Behav. 2019, 45, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, N.; Cross, D.; Monks, H.; Waters, S.; Falconer, S. Current Evidence of Best Practice in Whole-School Bullying Intervention and Its Potential to Inform Cyberbullying Interventions. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 2011, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, A.; Sulla, F.; Santamato, M.; Cipriano, A.; Cella, S. The Long-Term Efficacy and Sustainability of the Tabby Improved Prevention and Intervention Program in Reducing Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. Cyberbullying and Self-Esteem. J. Sch. Health 2010, 80, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, N.A.; Yahaya, W.A.J.W.; Muniandy, B. The Use of Multimedia in Increasing Perceived Knowledge and Awareness of Cyber-Bullying among Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 176, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. A cross-cultural comparison of adolescents’ experience related to cyberbullying. Educ. Res. 2008, 50, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusinga, S.; Kyobe, M. Towards a Mobile Application for Monitoring and Reporting Mobile Victimisation Among South African High School Students. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterwyk, G.; Kyobe, M. Mobile bullying in South Africa—Exploring its nature, influencing factors and implications. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Warfare and Security, ECCWS, Jyväskylä, Finland, 11–12 July 2013; p. 2007. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/ed2e0e29b98e3688f2f4fc21fd0a23bf/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=396497 (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Popovac, M.; Leoschut, L. Cyber Bullying in South Africa: Impact and Responses; Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention: Cape Town, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kyobe, M.; Lusinga, S. Factors in Reporting Mobile Victimization in South African Schools. In Bullying Prevention and Intervention at School; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Xu, J. Children and adolescents’ understanding of traditional and cyberbullying. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 139, 106528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, H.; Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying perpetration and victimization: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2021, 17, e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffney, H.; Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M. Examining the Effectiveness of School-Bullying Intervention Programs Globally: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019, 1, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, L. Perceptions and experiences of cyberbullying amongst university students in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. J. Transdiscipl. Res. S. Afr. 2021, 17, a776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, S.; Rizzi, S.; Carbone, S.; Piras, E.M. School interventions for bullying–cyberbullying prevention in adolescents: Insights from the upright and creep projects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfalah, A.A. Factors influencing students’ adoption and use of mobile learning management systems (M-LMSs): A quantitative study of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.F. Adolescent Cyberbullies’ Attributions: Longitudinal Linkages to Cyberbullying Perpetration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelga, S.; Postigo, J.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Cava, M.-J.; Ortega-Barón, J. Cyberbullying among adolescents: Psychometric properties of the CYB-AGS cyber-aggressor scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choong, W.W.; Mohammed, A.H.; Alias, B. Energy Conservation: A Conceptual Framework of Energy Awareness Development Process. Malays. J. Real Estate 2006, 1, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, M.A.; Salehi, S.; Ghazal, S.; Ybarra, V.T.; Naqvi, S.A.M.; Cokely, E.T.; Teodoriu, C. Situational awareness measurement in a simulation-based training framework for offshore well control operations. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2019, 62, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R.; Garland, D.J. Theoretical Underpinnings of Situation Awareness: A Critical Review. Situational Aware. Anal. Meas. 2010, 1, 24. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8d9a/0c84420495d1f406b27d4c0ba3b9f7a65d45.pdf?_ga=2.200901869.2101231965.1569842362-2078601259.1520864313 (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Webb, J.; Ahmad, A.; Maynard, S.B.; Shanks, G. A situation awareness model for information security risk management. Comput. Secur. 2014, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Endsley Design and Evaluation for Situation Awareness Enhancement. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1988, 32, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Toward a Theory of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems. Hum. Factors 1995, 37, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Situation Awareness Misconceptions and Misunderstandings. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 2015, 9, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, V.R.; Trajano, R.P.; Kravitz, R.L.; Bell, R.A.; Vora, D.; May, L.S. Communication interventions to promote the public’s awareness of antibiotics: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Parent, N.; Bond, T.; Sam, J.; Shapka, J. Developmental Trajectories of Cyber-Aggression among Early Adolescents in Canada: The Impact of Aggression, Gender, and Time Spent Online. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paley, N. The Manager’s Guide to Competitive Marketing Strategies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P. Market-Timing Strategies that Worked. J. Portf. Manag. 2002, 29, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofre, S. General Rights Strategic Management: The Theory and Practice of Strategy in (Business) Organizations. DTU Management. DTU Management 2011 No. 1. Available online: https://orbit.dtu.dk/en/publications/strategic-management-the-theory-and-practice-of-strategy-in-busin (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Lahtinen, V.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Long live the marketing mix. Testing the effectiveness of the commercial marketing mix in a social marketing context. J. Soc. Mark. 2020, 10, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomering, A. Marketing for Sustainability: Extending the Conceptualisation of the Marketing Mix to Drive Value for Individuals and Society at Large. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, R.J.; Egger, G.; Kapernick, V.; Mendoza, J. A Conceptual Framework for Achieving Performance Enhancing Drug Compliance in Sport. Sports Med. 2002, 32, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borden, N.H. The Concept of the Marketing Mix’. J. Advert. Res. 1964, 4, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pouwelse, M.; Mulder, R.; Mikkelsen, E.G. The Role of Bystanders in Workplace Bullying: An Overview of Theories and Empirical Research. In Pathways of Job-Related Negative Behaviour; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, I.; Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M. Protective factors against bullying and cyberbullying: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Aggress. Violent. Behav. 2019, 45, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkland, E.C.; Wiggins, M.W. Cross-Task cue utilisation and situational awareness in simulated air traffic control. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 74, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, V.L.; Williams, S.M.; Mann, J.I.; Schofield, G.; McPhee, J.C.; Taylor, R.W. Change of school playground environment on bullying: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20163072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, K.; Lyons, M.M.; Carr, S.A. Revisiting media richness theory for today and future. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 1, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, L.V. Media Richness and Message Complexity as Influencers of Social Media Engagement. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Fullerton, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sheer, V.C. Media Richness Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Psychology; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Direct Objective Measures of Situation Awareness: A Comparison of SAGAT and SPAM. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2019, 63, 001872081987537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mathimbi, P. A Framework for Developing Awareness Interventions: A Case of Mobile Bullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050774

Mathimbi P. A Framework for Developing Awareness Interventions: A Case of Mobile Bullying. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050774

Chicago/Turabian StyleMathimbi, Portia. 2025. "A Framework for Developing Awareness Interventions: A Case of Mobile Bullying" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050774

APA StyleMathimbi, P. (2025). A Framework for Developing Awareness Interventions: A Case of Mobile Bullying. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050774