Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Measures

2.2. Participants

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Eco-Anxiety

3.2. Eco-Guilt

3.3. Eco-Grief

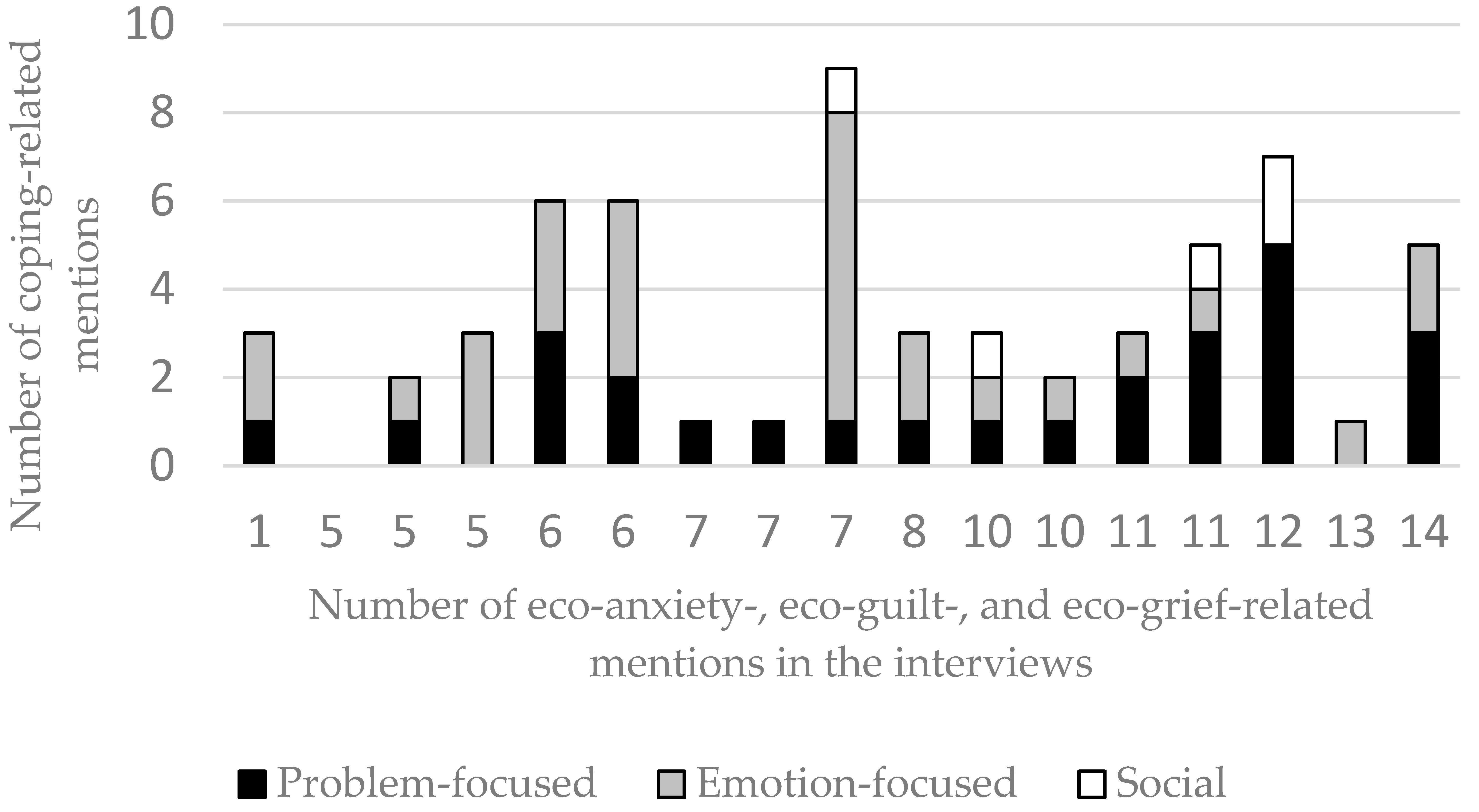

3.4. Coping Mechanisms

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| What is your first association with climate change? |

| What do you think about the credibility of the news about climate change? |

| Where do you find information on environmental/climate change topics? How do you select these resources? |

| How does climate change currently affect your life? |

| How do you think climate change will affect the lives of future generations? |

| How do you feel when you think about climate change? |

| Can you recall anything that you think has changed permanently and irreversibly as a result of climate change? Please tell us more about this. |

| Who do you think is responsible for protecting the environment and mitigating climate change? Why? |

| What do you think people do in general to protect the environment or stop climate change? |

| What do you do to protect the environment? |

| What do you think other people would do (and what they would not do) to protect the environment or stop climate change? |

| All in all, what are the most important environmental issues that you think we need to address at the societal level or at the individual level? |

Appendix B

| Theme Names | Description of the Themes | Example of the Initial Code in the Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Emotions | Emotions explicitly or indirectly expressed in the interview, quotes with a strong emotional charge | Was disturbed by the sight of too cheerful people |

| Sense of being affected by climate change | Personal episode or event related to the effects of climate change experienced by the participants on their own | Increased symptoms related to barometric pressure |

| Key experiences | An event or a concrete experience that can be considered as a turning point in the participants’ attitudes in terms of climate change | A book made her aware of the gravity of the situation |

| Relationship with nature | Codes that describe the participants’ relation to nature | Respect for each other’s living space |

| Past | Codes concerning the past (e.g., what the weather was like in the past, what was different, or what the participant did in the past) | Bees, birds, plants—everything has become different |

| Present | Codes concerning the present | There are many more forest fires these days |

| Future | Visions, expected events, happenings, scenarios related to climate change | More and more things will have to be imported to Hungary |

| Fantasy | The participants’ desires, dreams, wishful thinking | Conducting solar energy from space to the Earth by using a huge particle accelerator |

| Responsibility | The participants’ statements regarding responsibility | The responsibility of multinational companies is far greater than that of individuals |

| Participant’s own action | Steps, actions, participation taken by the participant | Uses fewer chemicals in the household |

| Other’s action | Codes describing the actions, non-actions, and behavior of others mentioned by the participant | Others may be willing to collect waste separately |

| Age/generational differences | Codes for generational differences, statements about childhood or the elderly | It is more difficult for older people to develop new habits |

| Characterization of people/groups | Statements about specific individuals (e.g., Greta Thunberg) or groups (e.g., climate change deniers, politicians, people who live in cities, etc.) and general descriptions of human nature, which can be considered as a kind of folk psychological characterization | Grew up in the countryside where love of nature and living things is a fundamental value for people |

| Conflicts | Quotes that reflect conflicting situations resulting from the participants’ sustainable behavior | Conflict with the family because she talks too much about the topic |

| Social influence | Codes related to persuading people, changing their behavior, the possible means of influence, the participants’ influence on other people | The influence of celebrities on policymakers |

| Hypothetical/desired/necessary actions | What further steps the participants consider important, what they hope for, what would be needed; quotes related to the planned or desired personal actions | Instead of individual action, pressure should be put on factories |

| Specific actions implemented | Statements about measures taken, organizations, inventions | Several zero packaging stores opened in Budapest |

| International comparison | Comparison of countries, evaluation of climate change measures of other countries or their own country (Hungary) | In developed societies, there are more movements that draw people’s attention to environmental protection |

| Explanations | The explanations the participants give about certain phenomena related to climate change, the theories they have, as well as the factors and moral issues that hinder sustainable behavior | The question of livelihood always overrides our attention to the environment |

| Processes | The participants present various interacting phenomena and processes | Deforestation disrupted an island’s ecosystem |

| Specific phenomena | Specific events and phenomena observed in nature; polluting activities | True bugs do not freeze in winter |

| Gathering information | Codes for gathering news and information related to climate change | The authenticity of news is difficult to verify |

| Skepticism | Doubts about climate change mitigation actions, leaders and decisionmakers, and climate change itself | There have been forest fires before |

| Ambivalence/irony | Codes related to self-mocking humor; the participants’ self-reflected responses and ambivalence about some actions | Questioning one’s own credibility on the subject |

| Metaphors | The participants characterize a phenomenon related to climate change with a metaphor or a poetic description | As if we were sitting on a sinking ship |

| Quitting from the context of the interview | The participants reflect on the interview situation or address the interviewer (e.g., they want to convince the interviewer of something) | Advises the interviewer to visit a website |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2007—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, H.L.; Bowen, K.; Kjellstrom, T. Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, H.L.; Waite, T.D.; Dear, K.B.G.; Capon, A.G.; Murray, V. The case for systems thinking about climate change and mental health. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.K.; Hogg, T.L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo Willox, A.; Harper, S.L.; Edge, V.L.; Landman, K.; Houle, K.; Ford, J.D.; The Rigolet Inuit Community Government. The land enriches the soul: On climatic and environmental change, affect, and emotional health and well-being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Emot. Space Soc. 2013, 6, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleres, J.; Wettergren, Å. Fear, hope, anger, and guilt in climate activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2017, 16, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, M.; Axon, S.; Sovacool, B.K.; Sareen, S.; Furszyfer Del Rio, D.; Axon, K. Contextualizing climate justice activism: Knowledge, emotions, motivations, and actions among climate strikers in six cities. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 65, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. Chronic Environmental Change: Emerging ‘Psychoterratic’ Syndromes. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being. International and Cultural Psychology; Weissbecker, I., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, L. Emotional Resiliency in the Era of Climate Change: A Clinician’s Guide; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett, R.K.; Melchiori, K.J.; Strickroth, T. Self-Confrontation via a carbon footprint calculator increases guilt and support for a proenvironmental group. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Toward a Taxonomy of Climate Emotions. Front. Clim. 2022, 3, 738154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K.; Durkin, J.; Bhullar, N. Eco-Anxiety: How thinking about climate change-related environmental decline is affecting our mental health. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 1233–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verplanken, B.; Roy, D. My worries are rational, climate change is not: Habitual ecological worrying is an adaptive response. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, A.J.; Akinola, M.; Martin, A.; Fath, S. The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety Stress Coping 2017, 30, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, J.H.; Klug, S.; Bamberg, S. Guilty conscience: Motivating pro-environmental behavior by inducing negative moral emotions. Clim. Change 2015, 130, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.M.; Yang, J.Z. Using Eco-Guilt to Motivate Environmental Behavior Change. Environ. Commun. 2020, 14, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M.; Hughes, K. Eco-Guilt and eco-shame in tourism consumption contexts: Understanding the triggers and responses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1223–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.A.; Branscombe, N.R. Collective guilt mediates the effect of beliefs about global warming on willingness to engage in mitigation behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graton, A.; Ric, F.; Gonzalez, E. Reparation or reactance? The influence of guilt on reaction to persuasive communication. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 62, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillaud, S.; Krauth-Gruber, S.; Bonnot, V. Facing Climate Change in France and Germany: Different Emotions Predicting the Same Behavioral Intentions? Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, G.L.; Reser, J.P.; Glendon, A.I.; Ellul, M.C. Distress and coping response to climate change. In Stress and Anxiety: Applications to Social and Environmental Threats, Psychological Well-Being, Occupational Challenges, and Developmental Psychology Climate Change; Kaniasty, K., Moore, K.A., Howard, S., Buchwald, P., Eds.; Logos Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress Coping 2008, 21, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.; Leiserowitz, A. The role of emotion in global warming policy support and opposition. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hiser, K.K.; Lynch, M.K. Worry and Hope: What College Students Know, Think, Feel, and Do about Climate Change. J. Community Engagem. Scholarsh. 2021, 13, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Minor, K.; Agneman, G.; Davidsen, N.; Kleemann, N.; Markussen, U.; Lassen, D.D.; Rosing, M. Greenlandic Perspectives on Climate Change 2018–2019: Results from a National Survey; University of Greenland: Nuuk, Greenland; University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark; Kraks Fond Institute for Urban Research: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbooks in Psychology. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol. 2. Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The psychological impacts of global climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mallett, R.K. Eco-Guilt Motivates Eco-Friendly Behavior. Ecopsychology 2012, 4, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald, N.; Schoenebeck, S.Y.; Forte, A. Reliability and Inter-Rater Reliability in Qualitative Research: Norms and Guidelines for CSCW and HCI Practice. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 3, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, S.F.; Seligman, M.E. Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1976, 105, 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefcourt, H.M. Locus of Control. In Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes, Vol. 1. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes; Robinson, J.P., Shaver, P.R., Wrightsman, L.S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 413–499. [Google Scholar]

- Soutar, C.; Wand, A.P.F. Understanding the Spectrum of Anxiety Responses to Climate Change: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyle, K.J.; van Susteren, L. The Psychological Effects of Global Warming; National Wildlife Federation: Reston, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kőváry, Z. Bevezetés: Föld és lélek—klímaválság és pszichológia. Imágó Bp. 2019, 8, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D. Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovarauskaite, L.; Böhm, G. The emotional engagement of climate experts is related to their climate change perceptions and coping strategies. J. Risk Res. 2020, 24, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudon, P.; Jachens, L. A Scoping Review of Interventions for the Treatment of Eco-Anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.L.; Reser, J.P. Adaptation processes in the context of climate change: A social and environmental psychology perspective. J. Bioecon. 2016, 19, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, S.E. Online Confessions of Eco-Guilt. J. Study Relig. Nat. Cult. 2014, 8, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.E. Psychometric Properties of the Climate Change Worry Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant ID | Sex | Age | Residence | Relevant Expertise/Profession |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 28 | Capital city | Chemical engineer, Master’s degree in Sustainable Development |

| 2 | Male | 28 | Capital city | Committed to climate change mitigation |

| 3 | Male | 19 | Another city | Has a strong opinion on the topic |

| 4 | Male | 20 | Another city | Psychology student |

| 5 | Male | 30 | Village | Animal rights activist, animal caretaker |

| 6 | Male | 22 | Another city | Student in teacher training with environment-related subject specialization |

| 7 | Female | 20 | Capital city | Committed to climate change mitigation, Sociology student |

| 8 | Female | 77 | Capital city | Strong climate sensitivity due to age, previously worked as a statistician |

| 9 | Female | 20 | Capital city | Environmental activist (Extinction Rebellion) |

| 10 | Female | 23 | Village | Conservation engineer |

| 11 | Female | 35 | Capital city | Committed to climate change mitigation, yoga instructor |

| 12 | Female | 30 | Capital city | Committed to climate change mitigation |

| 13 | Female | 22 | Capital city | Interested in climate change mitigation, but not yet an activist |

| 14 | Female | 52 | Another city | Teacher (English and Chemistry) |

| 15 | Female | 26 | Another city | Environmental activist, environmental Facebook group administrator, social worker |

| 16 | Female | 43 | Capital city | Committed to climate change mitigation, teacher, very religious (Christian) |

| 17 | Female | 33 | Capital city | Environmental activist (Extinction Rebellion) |

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Future and next generations | “But if we don’t start taking some drastic steps for this matter, future generations will come off badly. Anyway, I feel really sorry for the next generation, I’ve already been feeling sorry for my future children for what they will be born into if people don’t bring about some huge change” (Participant 6). |

| Empathy | “Yeah, so a lot of people can already feel its direct effects. I’m a social worker, I’ve worked in elderly care, and I see how much the number of deaths is accelerating in the winter or summer period” (Participant 15). “For example, there was this documentary on Netflix, and David Attenborough’s series, and although it didn’t aim to blame people, but it pointed out that the way we live [is harmful/unsustainable], and the animals are those who feel the direct effects of it, and they are not able to do anything about it; and only we, people, can do something about it” (Participant 15). |

| Conflicts | “Well, I haven’t experienced this [eco-anxiety] so continuously, so strongly, but I always feel that I’m worried about it, but less strongly. But there were two occasions when I felt it very strongly. Once, after reading this study, and then I cried and told my mom that everything is meaningless and things like that. And yet I think I’m basically a pretty optimistic person. The other time was when we travelled to Gran Canaria for the second time this summer. I mean, we were there last year and the flight there was a total of 11 h, I mean, it was 11 h back and forth. And then I saw that the people there were all so cheery and it was like there was nothing wrong and I became so upset that I kept talking about it and that made my mom and brother angry, and they told me to shut up. And ironically, a few days after we had left a huge forest area caught fire, and the forest burned down also in places that we had visited earlier. So that was very tough” (Participant 9). |

| Being disturbed by the changes | “And really, there were times when we worried about when it was going to rain. Though people can really worry about a lot of things in their lives, this has not been among them so far. This has been a given so far, we haven’t had to worry about nature because nature has been doing its duties. But we meddled with it so much that the whole thing has become completely unpredictable, and this unpredictability is not good for anyone” (Participant 17). |

| Mental health symptoms | “There are times when I feel anger. Or panic. Yes, I definitely feel panic sometimes. For example, when I think about how many clothes are burned every year in the fast fashion industry. I mean, I don’t live my life like I’m cooking in the kitchen and I panic about it, but when I think about all of it that oh my God, what is this all about, how much oil flows into the Danube or the sea or anywhere… So, yes, I panic” (Participant 15). |

| Helplessness, frustration | “I used to see one article a month, and then when you read every day that the planet is in flames, we’re going to die, everything is bad, no one is helping anyone, I think it induces a process: I’m dealing with this topic more and because I feel helpless, that’s why I’m anxious” (Participant 12). |

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Prophetic individual responsibility | “And if I don’t acquaint people with the idea, explain it to them, educate them, and show the harm, then they won’t understand and then they won’t do anything” (Participant 5). |

| Self-criticism, self-examination, self-blame | “(…) Or, for example, when I thought about how many sanitary pads I was going to use as a woman, a fertile woman, in my following 20–30 active years. And I decided to switch to reusable sanitary pads on my 27th birthday” (Participant 15). “I ask myself from time to time what else I could do to act in a more environmentally friendly manner” (Participant 2). |

| Guilt/individual responsibility criticism | “I had a very interesting conversation with one of my acquaintances. He was the one who said that he thinks this whole environmentalism is harmful to the environment. In fact, the individual contribution to pollution is so little compared to how much waste factories emit. And by persuading the well-educated, wealthier classes who could lobby factories to facilitate change… With all sorts of bullshit messages like “Recycle!”, “Turn off the lights!”, “Be vegan!”, and so on… they feel like they’re doing something for the environment. But it rather prevents them from going above a certain level of anxiety and tension so they don’t force factories to make radical changes” (Participant 13). |

| Dissatisfaction with one’s actions | “I often feel that what I can do is far from enough” (Participant 7). “I also feel a little bit guilty that I don’t really care about this topic right now because there are some very enthusiastic climate advocates even in the closest circle of my friends. And when I somehow scrambled home between two parties yesterday, I had a kebab in my hand, and I was so full that I threw away the leftover. And I’ve been feeling guilty ever since” (Participant 4). |

| Feeling guilty about one’s past | “(…) I also felt something like that, that the way I have lived over the last 10–30 years has also contributed to this” (Participant 17). “Then there is the issue of housekeeping, for example. I was kind of a compulsive cleaner, a person who kept everything clean. I couldn’t stand it if there was a stain on the table or counter and… I used very, very strong chemicals” (Participant 15). |

| System maintenance guilt | “(…) Because of the daily comfort of people and the whole system—capitalism and globalism—built on it. And because of them, it is simply inevitable that you will be a part of it” (Participant 17). |

| Dilemma of harm | “At the same time, I have to think about it, if my products include tropical fruit in January, which is not seasonal at all, am I doing more damage than he does by using plastic bags?” (Participant 15). |

| Guilt for one’s existence | “(…) But then I felt such remorse that I produce a lot of unnecessary rubbish just through my existence, and it really caused unpleasant feelings on a daily basis. And then I tortured myself a lot by saying that the way I exist and… I don’t know, my needs and the things I do, like my job, are not indispensable… and it was so depressing” (Participant 16). |

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Loss of the physical environment and species | “It also makes me sad because I have noticed that I don’t see a lot of plants anymore that I used to see when I was young. I have never really dealt with insects, I mean like in more detail, but I have read about them dying en masse. But what I terribly miss is birds. We’ve been travelling to Őrség [a region in Hungary] every year for 10 years, and when we first went there in the summer, I remember what we saw there, what kind of bird chatter greeted us. And now I look for them in vain” (Participant 8). |

| Anticipated future losses | “Well, on the one hand, I grew up watching the movies of David Attenborough and I like the diversity of species very much, and when I read about extinction and decreasing populations, it breaks my heart that this diversity and beauty is withering. And the things I could see in the nineties, and in the current documentaries of David Attenborough… it is possible that in two years we could see only in video recordings how birds-of-paradise flutter in the forest, and it sucks” (Participant 1). |

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Taking actions/planning | “And to be honest, after I joined Extinction Rebellion, I felt for the first time that I was doing something useful or I was actually doing something, and maybe that helped, too” (Participant 9). “(…) To give back to nature what belongs to nature. To be involved more actively in producing even less garbage. You know, this zero waste thing, which I haven’t achieved yet… it is very difficult to achieve anyway. So, I have tips like that. I think that from the moment a person is actively involved in action, the whole situation becomes less threatening…” (Participant 6). |

| Confrontation | “And then that’s when I get upset. Really, I can give an example from my narrowest circle of friends that I do have to tell them not to ask for a straw for their drink, it should be so obvious, why would you need it? You can drink your beverage without it, why is it so important now?” (Participant 6). “What really bothered me was people’s indifference. I didn’t know what to do with that. Their bad decisions… I had such a defining moment last year that although I liked those people, I was really angry with them because they took the car to a dining place that was only 5 min from us just because it was hot outside. And I looked at them like ‘Are you serious?’” (Participant 7). |

| Positive reappraisal, optimism | “So, I don’t think there will be such a big cataclysm here, I still believe in human goodness and eagerness for action” (Participant 10). “I wouldn’t really say I’m pessimistic and depressed about it, but let’s say it’s urging and motivating me” (Participant 16). “I can see that a lot of things are not worth worrying about. Technological innovation is the thing that definitely needs to be done, because it is so great, and it’s so good to read about it, and it’s really a matter of power games” (Participant 13). “These consequences may be known to some extent, so I’m not really worried about it [climate change], and I also know that God holds all of this in His hands, and I know what the end of this will be because the end will be a happy ending” (Participant 16). |

| Withdrawal/acceptance | “(…) The phrase ‘environmental protection’ is truly misleading because it is much more about the protection of humanity. Because the environment will survive and regenerate anyway, but people will not” (Participant 13). “Well, it’s such a very weird thing, because there are these five stages of grief, and these can also be applied to those who are diagnosed with a terminal illness. And then denial is the very first, you know. Then, when you get over it, you accept it in some way. And these five stages appeared alternately during the summer. Because along with Greta Thunberg, it all intensified, more and more people started sharing the news about it. And the UPFSI or UPFRS, I don’t know the acronym right now, has a channel on YouTube and I’ve seen two videos there, which have already made it clear that this is irreversible, and a lot of lectures, too. And Jem Bendel who worked for the IPCC or made reports, if I’m not wrong, and I think he’s working as a climate change researcher at the University of Bristol, he has already started a grief therapy group” (Participant 11). |

| Problem avoidance/denial/ wishful thinking | “But since I haven’t opened these articles anymore lately so they wouldn’t haunt me, I can only say what I thought about this half a year ago. Since then, I don’t know how bad the situation has become, but I don’t think it has changed because I haven’t heard that some miracle has happened and that everyone has really reacted to it” (Participant 12). “Well, what I can do to block this out is that I try to achieve different flow experiences by learning, doing yoga, fine arts, or some, I don’t know, cultural programs” (Participant 11). “But I’ve been thinking about it, and it would be so nice if people suspended all their actions for five years, didn’t go to college, work, but rather cleaned up the Earth, got the garbage out of the oceans, and figured out what to do with the garbage” (Participant 7). |

| Social support | “And then the way I was able to take part in Extinction Rebellion, it [the eco-anxiety] eased and I don’t think about it every day anymore, but only sometimes when I see the news, I get sad about it. This community can give me a lot and it’s very motivating that I’m in a company where others think and feel the same way I do. And the good thing about this company is that we do not talk about this topic all the time but we do talk about it as well, and that dissolves it all, and at the same time a community is forming that I’m very happy to join” (Participant 9). “It really bothered me that nobody in my milieu cared about these things. And then I secretly started looking for communities that cared, reading, and attending talks and things like that, where this climate issue is more in the focus of attention” (Participant 17). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ágoston, C.; Csaba, B.; Nagy, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Dúll, A.; Rácz, J.; Demetrovics, Z. Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042461

Ágoston C, Csaba B, Nagy B, Kőváry Z, Dúll A, Rácz J, Demetrovics Z. Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042461

Chicago/Turabian StyleÁgoston, Csilla, Benedek Csaba, Bence Nagy, Zoltán Kőváry, Andrea Dúll, József Rácz, and Zsolt Demetrovics. 2022. "Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042461

APA StyleÁgoston, C., Csaba, B., Nagy, B., Kőváry, Z., Dúll, A., Rácz, J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2022). Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042461