4. Discussion

The importance of proper dietary behaviors in terms of health and obesity prevention among children cannot be overestimated. Our study is one of few scientific studies on the dietary habits of children in Poland. In addition, our study is distinguished by a relatively large study group from different regions of the country. Analyzing the nutrition of the children examined, it is noteworthy that less than 1/5 of children have excessive body weight, and 6.8% of children are obese. According to data from the European COSI report co-created by WHO, and assessing the nutrition of European children aged 7–9 years and their selected health behaviors, an average of 29% of boys and 27% of girls in Europe are overweight, of which, 13% of boys and 9% of girls suffer from obesity. According to this report, the percentage of disorders among Polish children resulting from excessive body weight reaches a slightly higher level than average. Namely, the problem of obesity affects 14% of Polish boys and 10% of girls [

3]. In our study the problem of obesity concerned a smaller percentage of children; that is, 7.0% of girls and 6.6% of boys. According to the COSI study, 84.5% of studied children in Poland eat a first breakfast, whereas 1% do not eat that meal at all [

3]. The findings from the “Anthropometry, Intake and Energy Balance” (ANIBES) study are similar. The study reported that around 85% of the Spanish population (age range 9–75) were regular breakfast consumers, although one in five adolescents were breakfast skippers [

8]. Comparing the data obtained in our study regarding the first breakfast routine, they are better, as almost 92% of children eat breakfast as the first meal of the day. However, in another report evaluating eating behaviors among adolescents, the percentage of breakfast daily consumption declines to only 45%. The adolescents answered that the reason for breakfast skipping is most often a lack of time and appetite in the morning [

9]. Comparable results were also obtained in other reports [

10,

11]. According to Cheng et al., in a study that included 426 children aged 10–14 years from four local schools in Queensland, almost 1/3 children skip breakfast at least once during the school week. The study also revealed that skipping breakfast among children was associated with a lack of perceived parental emphasis on consuming breakfast [

12]. In a review by Gibney et al., it was found that healthy regular breakfast consumption is associated with improved cognitive health and nutritional status and lower plasma cholesterol levels among children and adolescents [

13]. Regarding dinner frequency consumption, Stefańska et al. indicate that dinner was the most frequently consumed meal (98.4–99.2% depending on gender and age) [

14]. These results are in accordance to those obtained in our study.

According to recommendations, vegetables and fruits should be dominant in the diet. Despite their availability, the daily consumption of such products is relatively low. According to the 2020 data of Statistics Poland, the monthly fruit consumption was 3.86 kg/person, whereas the vegetable consumption fluctuated around 7.72 kg/person. This gives approximately 270 g of these foods per day, and the absolute minimum for an adult is 400 g [

15]. When looking at our study, just over half of respondents eat fruits or vegetables daily, and nearly 40% eat those products only several times a week. However, according to the authors, the question asked in the study has some limitations because it does not specify the number of fruits and vegetables consumed per day and does not present the amounts of fruits and vegetables separately. Our study also found an interesting correlation between an increasing BMI and the consumption of fruits and vegetables. This may mean that parents of overweight children want to eat healthier because of the already existing weight disorder. In the study by Stefańska et al., this issue is discussed in more detail. The results showed that most children aged 10–12 consume raw fruits two to three times a day, with a statistically significant predominance of girls and boys in that age group compared to children aged 12–15 years. Among them, only 3% and 26.9% of girls and boys, respectively, ate fruits two to three times per day [

14]. It is observed that these data are in agreement with the study results of Harton et al.. In this study, the authors tried to assess dietary habits among preschool children aged 4–6. The results indicate that only one in four children ate fresh vegetables and one in two ate fresh fruits during the day. Regarding afternoon snacks, the consumption of fruits was claimed by the largest percentage of parents (approximately 40–45% depending on the child age) [

16]. Slightly better results were obtained in another study that was carried out among preschoolers as well. It reveals that little more than 50% of respondents eat fruits and vegetables one to two times a day. An alarming result is that nearly 20% (precisely—17%) of children eat fruit and vegetables less than once a day [

17]. It is worth noting that the consumption of fruit juices should not be considered as a valuable substitute for fruit due to the poor satiety effect after consumption and the high probability of drinking too much, which leads to an excessive supply of simple sugars. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines, fruit juice should not be given to children under 1 year old. However, after that period, the permissible consumption amounts of these products are as follows: 1–3 years—up to 120 mL/day, 4–6 years—up to 160 mL/day, 7–18 years—up to 200 mL [

18].

Another important issue in the discussion is the frequency of the consumption of both wholemeal flour bread and fish. In our study, the obtained results in this aspect are very poor. Approximately half of the studied children consume wholemeal flour bread less than once a week or do not eat it at all. According to the recommendations, products such as wholemeal flour bread are rich in polysaccharides, and hence should be eaten every day. This ensures an adequate energy supply and even consumption per unit time. It prevents glucose level fluctuations in the blood and hence prevents the consumption of simple sugars to quickly satisfy hunger. The level of the consumption of fish—foods rich in polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids, which are fat-soluble vitamins—leaves much to be desired. More than half of the children consume such products once a week, whereas approximately 30% consume them even less frequently. The results obtained in this regard are similar to those of other reports, which also highlighted the under-consumption of wholemeal flour bread [

19,

20,

21]. In Stefańska’s study [

14], this kind of bread is the preferred choice for half as many girls and boys as light bread. Wholemeal flour bread was consumed every day by approximately 11–15% of children aged 10–12, whereas only approximately ¼ of children consume this product several times a day. In the largest group of children, approximately 40%, consume wholemeal flour bread less than 2–3 times a week [

14]. This is slightly better than the percentage obtained in our study, but is still insufficient. Furthermore, according to cited study, fish is consumed by 70% of children less than two to three times per week [

14]. According to the obtained data from Fernandez et al. in a Spanish study, 12% of studied children rejected eating fish at all. Only 2% of children ate fish daily. The most commonly consumed food by Spanish school children were “pasta” and rice, soft drinks, juices and fruits (bananas, apples and oranges), cakes, tomato, snacks and fast food [

22].

The main beverage for both children and adults should be water. The Guidelines for Nutrition Standards in Poland recommend that children aged 6–9 should drink approximately 1600–1750 mL of water per day, which makes approximately six to seven glasses of water [

23]. It is important to know that pure water provides the best hydration for the body, i.e., 100 g of water consumed means 100 mL of functional water obtained. The addition of 10 g of glucose reduces the functional water content to only 60 mL [

24]. Compared to other European countries, the percentage share of various beverages consumed by children during the day in Poland is to the disadvantage of pure water. In Poland, among children aged 7–9, only 13% of the total fluid consumption is pure water, whereas, in other countries, this percentage increases to approximately 25–43% depending on the age of children [

25]. A large study from 2015 focused on the quantity of liquids, including water, consumed by children living in 13 different countries on different continents. The study group was divided by age, namely, the first group included children aged 4–9, whereas the second group included children aged 10–17. The results showed that, among all of the children studied, water was the most common drink and was consumed at an average of 738 ± 567 mL/day. Poland also took part in the study, but the results obtained in our country are unsatisfactory and significantly different from other countries surveyed. Namely, according to the received data, the daily water consumption in Poland by children aged 4–9 is 17% for both girls and boys. In the group of older children, this percentage is slightly higher, i.e., 23% of girls and 20% of boys. According to the results of this study, the largest group of children in Poland, i.e., approximately one-third, consumed hot beverages during the day [

26]. In our survey, according to the respondents, water was the most common drink among children. Almost ¾ of children drink water every day, but there is still ¼ of children who do not drink water every day. As many as 15.5% of children drink water only several times a week, which indicates that this group of children is much more likely to drink other liquids to quench their thirst. In addition, the popularity of buying water from the school cafeteria is low and is reported by only 4.5% of children. An interesting fact is that children with a higher BMI drink more water. This may mean that children who are overweight and/or obese are making a more conscious effort to avoid unnecessary calories in the form of sugary drinks in favor of water. However, this only applies to children with potentially pre-existing weight disorders.

In the study by Kwiecień et al. [

27], water consumption among 1st and 3rd-grade elementary school students was more popular than in our study, with 78 and 83% of children in this age group drinking water daily, respectively. Research has shown the importance of consuming water instead of other sugary drinks in the prevention and treatment of obesity. The results of a randomized study conducted in Germany proved that the introduction of one glass of water per day to the diet of elementary school children reduces the risk of being overweight in 31% of the students studied. The observation period was one school year [

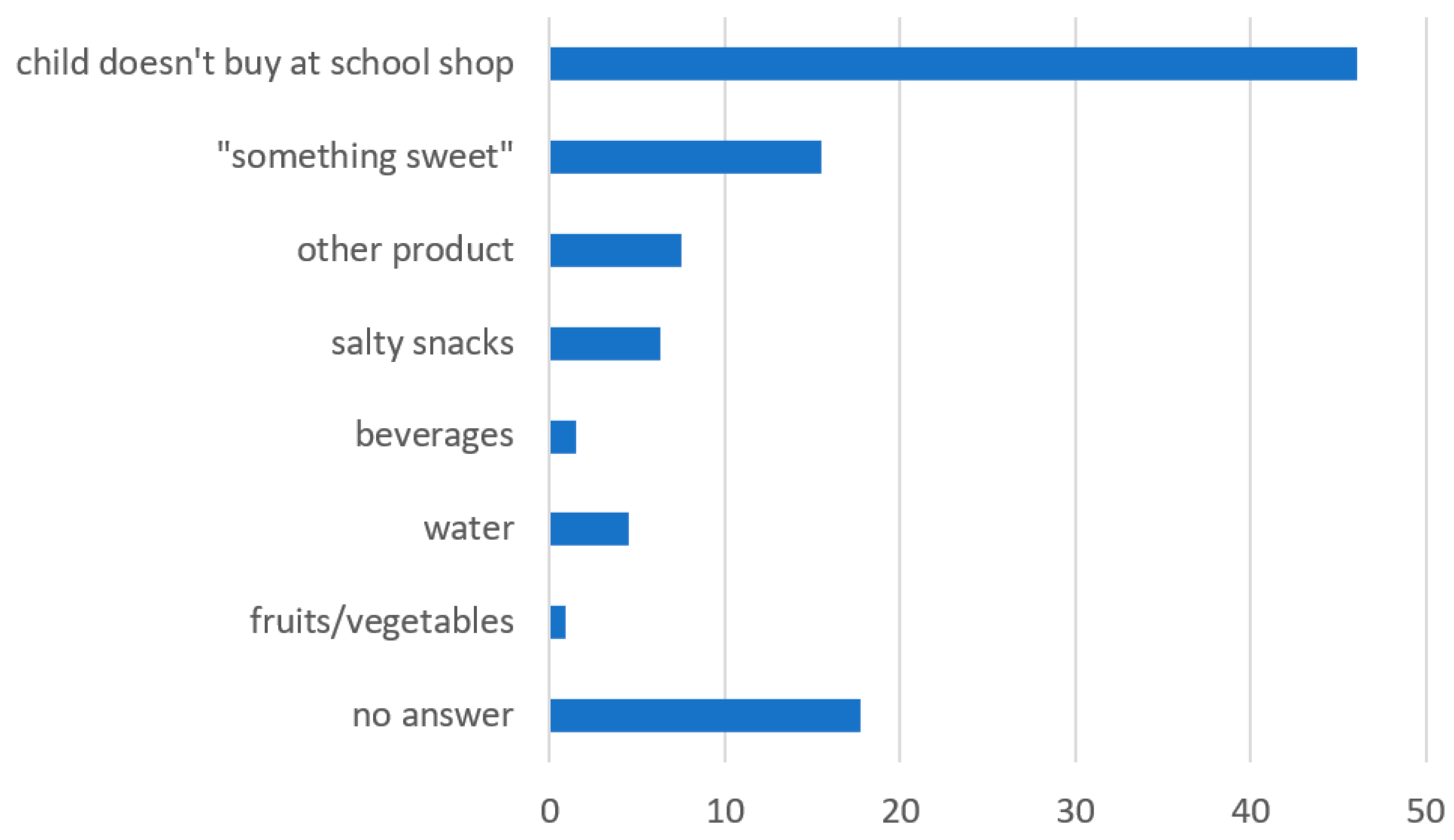

28]. When analyzing the consumption of sweets and sugary drinks by children, it can be seen that the consumption of those products is still high. The results show that sweets and sugary drinks are consumed daily or several times a week by a total of approximately half of the children studied. Additionally, “something sweet” was the most popular product in the school cafeteria. Other studies support those reports [

29,

30]. A meta-analysis dating back to 2017 showed that children are much more likely to choose high-calorie foods, such as candy, pizza and French fries, while watching TV. At the same time, significantly less fruit and vegetables are consumed [

31]. One of the more recent Polish studies focuses on assessing dietary habits during the COVID-19 lockdown. The study shows that, during the pandemic, the number of meals consumed during the day increased significantly, whereas the number of snacks consumed between meals increased by as much as 5%. Sweets were among the products whose consumption also increased during that time. On the contrary, the rate of the consumption of fast food meals, instant products and energy drinks decreased. In addition, 2/3 of respondents noticed changes in their body weight during lockdown. Even though the studied group were adults, according to the authors, the results of the study may largely translate to the pediatric population due to the closure of school facilities during that period [

32]. One of the newest articles also emphasizes the emotional and physiological implications of COVID-19 pandemic among children. The authors also review disturbances in sleep routines in the pandemic period [

33].

The final issue the authors are addressing is the role of proper nutrition education. It is important for both parents and children. Parents, by promoting proper dietary habits, will teach their children to perpetuate those habits. Additionally, according to research, home is a major determinant of children’s behaviors, including eating. Moreover, many poor dietary habits can reflect the parents’ lack of knowledge on the subject. By removing this factor, we have a chance for a better primary prevention of weight-related diseases, and thus better health. In 2019, there was a study published whose aim was to assess selected eating behaviors before and after the implementation of a 6-month nutrition education program among children aged 12. The research tool was a survey questionnaire conducted twice (before and after nutrition education) that included questions about selected dietary habits. The results showed that, in the educated group, there was an increase in the frequency of eating breakfast and lunch in the second assessment. The frequency of the consumption of milk and dairy products, fish and vegetables also increased in this group of children. The study also evaluated a decrease in the percentage of children consuming sugary drinks. The final evaluation also showed an increase in the proportion of both girls and boys with normal weight [

34]. Results obtained in the Dutch study performed with a much wider group of respondents also showed a positive relationship between parental nutrition education and the acquisition of healthier dietary habits [

35].

Our study also has some limitations. Due to the questionnaire-based nature of the study and the fact that parents entered their child’s basic anthropometric measurements into the questionnaire themselves, the obtained distribution of the nutritional status of the examined children may differ from the real one, i.e., according to the authors of the present study, the percentage of children having excessive body weight may be underestimated. Moreover, questions concerning the frequency of the consumption of some food products did not specify the exact amount consumed per serving. The same is true for the frequency of the consumption of basic meals of the day, i.e., breakfast, dinner and supper. In particular, the analysis of the frequency of the supper intake poses difficulties in interpretation due to the lack of data concerning the products eaten as the last meal of the day and their quantities.

As for the survey methodology itself, the authors point out the poor response rate of 20.2%. According to the authors, this is due to several reasons. Firstly, the authors were not always present when the questionnaires were distributed at school, mainly during meetings with parents. Some of the parents did not fill out the questionnaires at those meetings and took them home. In most cases, the questionnaire was handed back to the teacher by the child, who often did not return it. Moreover, according to a large group of parents, the questionnaire was very difficult and contained too many questions. Some parents could feel ashamed of it. These facts may have been major reasons for the poor response rate obtained in the study.