A Qualitative Analysis of the Mental Health Training and Educational Needs of Firefighters, Paramedics, and Public Safety Communicators in Canada

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Resilience

1.2. Interventions

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

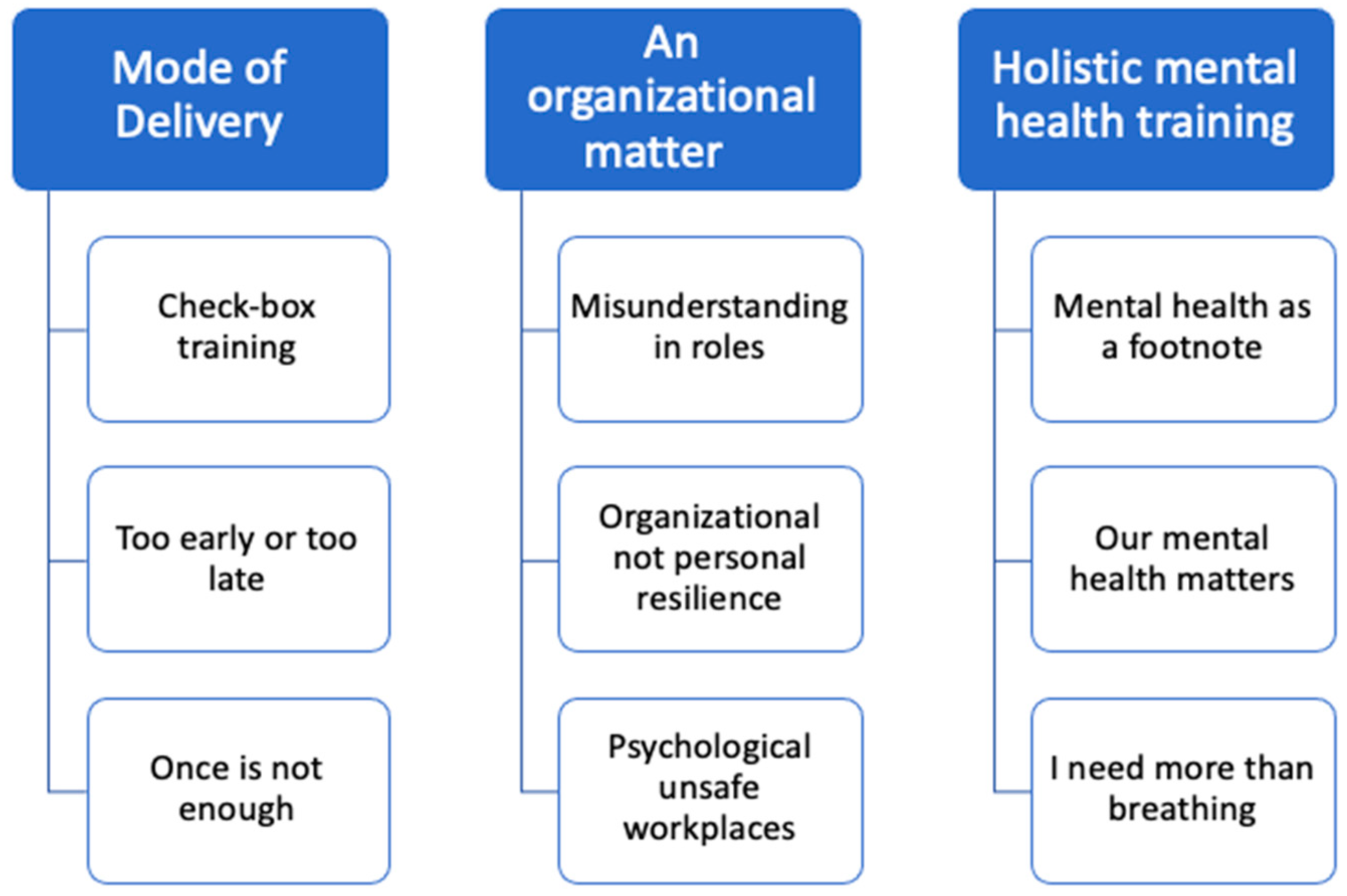

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Modes of Delivery

3.1.1. Subtheme 1: Check-Box Training

I just find that because everything is so online now, that it’s overused. (…) [A]re they actually going to get something out of it or are they just going to play the videos, click through, do something else, do their online shopping, instead of actually paying attention and what they should be doing.(Focus group—Paramedic)

So I don’t think I’m really into a course. I think we’ve done a lot of courses especially because of COVID-19. I think that the biggest hurdle that all of us have, in my experience, is we’re looking for help and we’re looking for someone that could understand us because we are different from civilians.(Focus group—Firefighter)

3.1.2. Subtheme 2: Too Little or Too Late

I think that we need to be recruiting for that a bit more and it [mental health or resilience education] needs to be a focus way early on and it needs to be embedded in our education and then it needs to be actual robust support and then you need to have that ongoing continual continuing education like these types of pieces of maintenance.(Interview—Paramedic)

I would suggest it may be helpful to do at school for a Paramedic, or Fire, or Police because going back to what XX is saying about not really knowing what you’re walking into. I don’t recall touching on anything psychological in PCP or Fire Fighting. I don’t know, earlier before you start the job maybe it would be beneficial going to school.(Focus group—Firefighter)

From a user perspective you know, almost like and it really should be ongoing, almost a self-checklist of key emotions that some people might be feeling that might be triggers that maybe they’re having some issues that would need to be addressed… Yeah, some kind of a self-check that they would do periodically would be important for them.(Interview—Public Safety Communicator)

3.1.3. Subtheme 3: Once Is Not Enough

Because I sit there on the receiving end of ‘here’s your other mandatory, here’s your other R2MR, here’s your this, here’s your this, here’s your this.’ … what I can’t echo … enough is … the focus of this learning and this education has to be system level. Once is not enough…(Focus group—Paramedic)

I think on our leadership side of things regarding mental health, there is a problem. They [leaders] could say, “we gave you that moral injury course.” So they check it off in their box and they know that they’ve done their job and that’s all they… It just kind of stops at that. But on their side that’s all their, “well we gave you this course, so now we’re good.” You know what I mean?(Focus group—Firefighter)

We do have things in place where the critical incidents are documented. The Call Takers reaction is documented and that is supposedly taken up the chain to our direct manager and I’m sure in some cases they’re followed up on but I don’t have any good examples of that.(Interview—Public Safety Communicator)

It’s like if you go fishing, you’re not going to expect a fish to jump in the boat. You can’t go fishing and be like, “where are all our fucking fish? They’re not jumping in the boat for us.” I hear that from so many different organizations. Like we have the CISM program. We have this program. We have EAP programs. We have all this stuff. What else are we supposed to do? I’m like, “oh my God. If that’s your attitude then…”(Focus group—paramedic)

3.2. Theme 2: An Organizational Matter

3.2.1. Subtheme 1: Misunderstanding of Roles

I spoke to this earlier…To mention the leadership course…That was just a series of questions that they get you to answer, then you tally a score, and then you take that score, and you do some circle pie chart that you scratch off different things. And then the instructor would say, “do not go ahead. Only do this step…”.(Focus group—Firefighter)

I think somewhere along the line, somewhere in some people’s minds, the supervisors, management, or anybody in a leadership position have some special, special training that we don’t. Or even how to deal with a person in crisis. I don’t have any training for that. Nor do I think I should. I should have a good idea of what resources are available to us to help us. Um, and to help identify when someone’s in crisis I guess, but even that is not the end-all, be-all, right?(Interview—Public Safety Communications Manager)

“[T]here’s a difference between leadership and managers and we have a collection of managers, there is a beautiful number of leaders throughout our profession they just may or may not have that rank on their shoulder and therefore don’t have the same type of influence and power connected to it”.(Focus group—Paramedic)

3.2.2. Subtheme 2: Organizational, Not Personal, Resilience

If the person experiencing the problem goes to leadership and they say “okay definitely take the rest of the day off, go for a walk, go for a jog, eat something good because XYZ”… That is going to go a long way to translating to people actually doing the things.(Interview—Public Safety Communicator)

Fixing the culture and mindset and the system of EMS would fix so much more of the retention issues and everything than just a little education at the beginning because you can introduce all of these courses and you’ll be a fresh-faced young paramedic and you’ll work with a 20 year paramedic that looks at you and is like, “Oh look at you and your nice thoughts about people actually being people. Let me show you how it really is.” These guys are animals. Okay… you need help.(Interview—Paramedic)

3.2.3. Subtheme 3: Psychologically Unsafe Workplaces

Moral injury…shows up in my workplace far more from the work culture environment than the calls themselves. And it shows up personally for me from everyday sexism at work from watching my peers experience that(Focus group—Paramedic)

I’ve been told this to my face. “Look, if these people are too weak to work here, I don’t want them here.” So that attitude is still there. … [A]nd it happens here in XXX, where paramedics … or fire fighters are getting pushed out because the employer doesn’t want them back because they feel they’re too weak(Focus group—Paramedic)

Leadership here in XXX right now is probably the best we’ve ever seen and right now would be the perfect time to, I don’t know… implement something because these guys understand. They’ve been on the floor; they understand how things work and how things are running. … those guys get it.(Focus group—Firefighter)

3.3. Theme 3: Holistic Mental Health Training

3.3.1. Subtheme 1: Mental Health as a Footnote

And there’s like domestic violence. Where the woman goes back to… I go to the same people all the fucking time and it’s like he beats the shit out of her and he’s like, “but we love each other.” And you just want to take him and beat the shit out of him. She’s got two black eyes now and you’re just like, “why the fuck don’t you leave this situation?”(Focus group—Paramedic)

How do I stay respectful to this intoxicated, clearly homeless, hasn’t washed in a very long time and smells terrible. How do I treat that person with the same care and respect as the 65-year-old grandmother I go to later who fell and broke her hip… And then we get the moral injury afterwards and I feel like a lot of it is self-inflicted because if we don’t learn it in school, we learn it from our preceptors, we learn it from our coworkers(Interview—Paramedic)

“Well, I’m very happy that we do have such an accepting process or an accepting stance on critical incidents but then um, the difference being having eight kind of rough ones, that’s basically the job. You know, you don’t sign up for pediatric cardiac arrest, but you do sign up for taking eight overdose calls”.(Interview—Public Safety Communicator)

3.3.2. Subtheme 2: Mental Health Matters

So, then I talk to the frontline guys and they say, “Yeah well, they say that they’re priority is mental health, but it seems like they just want to appear that way then actually doing stuff about it.” And I find that’s very common. So, I think, you know, it’s important for the idea or the concept to appear that their service has mental health as a priority that in some cases is more important to them than actually making the priority or prioritizing mental health.(Interview—Paramedic)

I don’t even think they’re doing okay with PTSD. I think we’ve just rounded a curve of attention on it. I will maybe give credit for attention on it, beyond that, the jury is out.(Focus group—Paramedic)

So if you actually… it’s one of two ways, either A) Just kind of practice what you preach or just tell us the truth that, “Hey, we believe in mental health, but we sure as shit aren’t going to fund it.” That’s fine. Just be honest with us because the disconnect, it’s the problem.(Focus group—Paramedic)

But the phone never stops. That workload doesn’t stop. So the answer some people will say is, “[W]ell just tell them to just take them out and have a talk with them for half an hour.” Haha.(Interview—Public Safety Communicator)

And it can’t be really fixed with a course. … [E]veryone has different morals and experiences; it needs to be more specific. I mean, courses will help, but it’s not going to fix us. I guess it’s education versus fixing. I don’t think it’s going to fix anyone in these situations. It might help educate myself, help my peers, or educate what’s going on inside but that’s all….(Focus group—Firefighter)

3.3.3. Subtheme 3: I Need More Than Just Breathing Exercises

We had to take R2MR, which is fine. It’s good information, however, it was nothing new. Nothing we don’t know. All it did was give us a name. So now when we’re angry instead of just being angry we start yelling, “I’m in the red! I’m in the red!” So it kind of became a running joke because yes, we know your partner is in the orange, we know you’re in the red, but it never gave anything for us to do.(Focus group—Paramedic)

We already have a program where certain employees have volunteered to be points of first contact and those employees… Yeah, they’re the ones that tell you to breathe, eat some soup, have a run, and then give you a phone number to call.(Interview—Public Safety Communicator)

We did some CISM training with the police and our experiences are pretty much similar…. Um, it was way better than taking CISM Training from someone who had never worked in the First Responder field. Because I think that courses were helpful, and I thought it was just so much better when the police did it because they had personal stories and they had examples of real-life situations… rather than just reading from a book.(Focus group—Firefighter)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; Macphee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Duranceau, S.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; MacPhee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. Psychol. Can. 2018, 59, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Queirós, C.; Passos, F.; Bártolo, A.; Marques, A.J.; Da Silva, C.F.; Pereira, A. Burnout and Stress Measurement in Police Officers: Literature Review and a Study With the Operational Police Stress Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, K.; Chopko, B. The Role of Moral Suffering (Moral Distress and Moral Injury) in Police Compassion Fatigue and PTSD: An Unexplored Topic. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Papazoglou, K.; Koskelainen, M.; Stuewe, N. Examining the Relationship Between Personality Traits, Compassion Satisfaction, and Compassion Fatigue Among Police Officers. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 215824401882519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT). Glossary of Terms: A Shared Understanding of the Common Terms Used to Describe Psychological Trauma (Version 2.0); CIPSRT: Regina, SK, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-MacDonald, L.; Lentz, L.; Malloy, D.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; Carleton, R.N. Meat in a Seat: A Grounded Theory Study Exploring Moral Injury in Canadian Public Safety Communicators, Firefighters, and Paramedics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, K.; Blumberg, D.M.; Chiongbian, V.B.; Tuttle, B.M.; Kamkar, K.; Chopko, B.; Milliard, B.; Aukhojee, P.; Koskelainen, M. The Role of Moral Injury in PTSD Among Law Enforcement Officers: A Brief Report. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; Mason, J.E.; Ricciardelli, R.; McCreary, D.R.; Vaughan, A.D.; Anderson, G.S.; Krakauer, R.L.; et al. Assessing the Relative Impact of Diverse Stressors among Public Safety Personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; Krakauer, R.; Anderson, G.S.; MacPhee, R.S.; Ricciardelli, R.; Cramm, H.A.; Groll, D.; et al. Exposures to potentially traumatic events among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Des. Sci. Comport. 2019, 51, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.J.; Purcell, N.; Burkman, K.; Litz, B.; Bryan, C.J.; Schmitz, M.; Villierme, C.; Walsh, J.; Maguen, S. Moral Injury: An Integrative Review. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, B.T.; Stein, N.; Delaney, E.; Lebowitz, L.; Nash, W.P.; Silva, C.; Maguen, S. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliphant, R.C. Healthy Minds, Safe Communities: Supporting Our Public Safety Officers through a National Strategy for Operational Stress Injuries; Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016.

- Antony, J.; Brar, R.; Khan, P.A.; Ghassemi, M.; Nincic, V.; Sharpe, J.P.; Straus, S.E.; Tricco, A.C. Interventions for the prevention and management of occupational stress injury in first responders: A rapid overview of reviews. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, J.; El-Salahi, S.; Degli Esposti, M.; Thew, G.R. Evaluating the effectiveness of a group-based resilience intervention versus psychoeducation for emergency responders in England: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, J.; El-Salahi, S.; Esposti, M.D. The Effectiveness of Interventions Aimed at Improving Well-Being and Resilience to Stress in First Responders: A Systematic Review. Eur. Psychol. 2020, 25, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada, Public Safety Canada. Supporting Canada’s Public Safety Personnel: An Action Plan on Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries. 2019. Available online: https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/weekly_acquisitions_list-ef/2020/20-34/publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/sp-ps/PS9-13-2019-eng.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Di Nota, P.M.; Bahji, A.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N.; Anderson, G.S. Proactive psychological programs designed to mitigate posttraumatic stress injuries among at-risk workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.S.; Di Nota, P.M.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N. Peer Support and Crisis-Focused Psychological Interventions Designed to Mitigate Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries among Public Safety and Frontline Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-S.; Ahn, Y.-S.; Jeong, K.S.; Chae, J.-H.; Choi, K.-S. Resilience buffers the impact of traumatic events on the development of PTSD symptoms in firefighters. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 162, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantoni, L.; Prati, G. Resilience among first responders. Afr. Health Sci. 2008, 8, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kunicki, Z.J.; Harlow, L.L. Towards a Higher-Order Model of Resilience. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Bonanno, G.A.; Masten, A.S.; Panter-Brick, C.; Yehuda, R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 25338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, W.P. Commentary on the Special Issue on Moral Injury: Unpacking Two Models for Understanding Moral Injury. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, I.T.; Cooper, C.L.; Sarkar, M.; Curran, T. Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: A systematic review. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological Resilience. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ungar, M. Social Ecologies and Their Contribution to Resilience. In The Social Ecology of Resilience; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, J.; Greenberg, N.; Moulds, M.L.; Sharp, M.-L.; Fear, N.; Harvey, S.; Wessely, S.; Bryant, R.A. Pre-incident Training to Build Resilience in First Responders: Recommendations on What to and What Not to Do. Psychiatry 2020, 83, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamontagne, A.D.; Keegel, T.; Louie, A.M.; Ostry, A.; Landsbergis, P.A. A Systematic Review of the Job-stress Intervention Evaluation Literature, 1990–2005. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2007, 13, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, K.M.; Rothstein, H.R. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: A meta-analysis. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, E.; Lampit, A.; Choi, I.; Calvo, R.A.; Harvey, S.B.; Glozier, N. Effectiveness of eHealth interventions for reducing mental health conditions in employees: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wessely, S.; Bryant, R.A.; Greenberg, N.; Earnshaw, M.; Sharpley, J.; Hughes, J.H. Does Psychoeducation Help Prevent Post Traumatic Psychological Distress? Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2008, 71, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaughan, A.D.; Stoliker, B.E.; Anderson, G.S. Building personal resilience in primary care paramedic students, and subsequent skill decay. Australas. J. Paramed. 2020, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, A.; Dobson, K.; Knaak, S. The Road to Mental Readiness for First Responders: A Meta-Analysis of Program Outcomes. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64 (Suppl. S1), 18S–29S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeto, A.; Dobson, K.S.; Luong, D.; Krupa, T.; Kirsh, B. Workplace Antistigma Programs at the Mental Health Commission of Canada: Part 2. Lessons Learned. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64 (Suppl. S1), 13S–17S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, R.N.; Korol, S.; Mason, J.E.; Hozempa, K.; Anderson, G.S.; Jones, N.A.; Bailey, S. A longitudinal assessment of the road to mental readiness training among municipal police. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018, 47, 508–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. xix. 391p. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, J.D. The building blocks of treatment in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2009, 46, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Padesky, C.A.; Mooney, K.A. Strengths-Based Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: A Four-Step Model to Build Resilience. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, S.; Shand, F.; Tighe, J.; Laurent, S.J.; Bryant, R.A.; Harvey, S.B. Road to resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e017858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGonagle, A.; Beatty, J.E.; Joffe, R. Coaching for workers with chronic illness: Evaluating an intervention. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, M.A.; Mamerow, M.M.; Brown, S.A.; Jolly, C.A. A Resilience Intervention in African-American Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2015, 39, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songprakun, W.; McCann, T.V. Effectiveness of a self-help manual on the promotion of resilience in individuals with depression in Thailand: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Catamaran, T.; Savoy, C.; Layton, H.; Lipman, E.; Boylan, K.; Van Lieshout, R.J. Feasibility of Delivering a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy-Based Resilience Curriculum to Young Mothers by Public Health Nurses. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 10, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.X.; Stewart, S.M.; Chui, J.P.; Ho, J.L.; Li, A.C.; Lam, T.H. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial to Decrease Adaptation Difficulties in Chinese New Immigrants to Hong Kong. Behav. Ther. 2014, 45, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stallard, P.; Simpson, N.; Anderson, S.; Carter, T.; Osborn, C.; Bush, S. An evaluation of the FRIENDS programme: A cognitive behaviour therapy intervention to promote emotional resilience. Arch. Dis. Child. 2005, 90, 1016–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallard, P.; Buck, R. Preventing depression and promoting resilience: Feasibility study of a school-based cognitive-behavioural intervention. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, s18–s23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steinhardt, M.; Dolbier, C. Evaluation of a Resilience Intervention to Enhance Coping Strategies and Protective Factors and Decrease Symptomatology. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 56, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, L.O.; Martindale-Adams, J.; Zuber, J.; Graney, M.; Burns, R.; Clark, C. Support for Spouses of Postdeployment Service Members. Mil. Behav. Health 2015, 3, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, F.; Irfan, M.; Javed, A. Coping with COVID-19: Urgent need for building resilience through cognitive behaviour therapy. Khyber Med. Univ. J. 2020, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamou, K.; Piedra, A. CBT-Informed Interventions for Essential Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2020, 50, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nota, P.M.; Kasurak, E.; Bahji, A.; Groll, D.; Anderson, G.S. Coping among public safety personnel: A systematic review and meta–analysis. Stress Health 2021, 37, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krick, A.; Felfe, J. Who benefits from mindfulness? The moderating role of personality and social norms for the effectiveness on psychological and physiological outcomes among police officers. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.B.; Bergman, A.L.; Christopher, M.; Bowen, S.; Hunsinger, M. Role of Resilience in Mindfulness Training for First Responders. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallie, M.S.; Blum, C.M.; Hood, C.J. Progressive Muscle Relaxation. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2006, 13, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, L.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Roettger, C.; Dixon, K.; Offenbächer, M.; Kohls, N.; Hirsch, J.; Sirois, F. Effectiveness of Progressive Muscle Relaxation, Deep Breathing, and Guided Imagery in Promoting Psychological and Physiological States of Relaxation. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5924040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taren, A.A.; Gianaros, P.J.; Greco, C.M.; Lindsay, E.; Fairgrieve, A.; Brown, K.W.; Rosen, R.K.; Ferris, J.L.; Julson, E.; Marsland, A.L.; et al. Mindfulness meditation training alters stress-related amygdala resting state functional connectivity: A randomized controlled trial. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2015, 10, 1758–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norelli, S.K.; Long, A.; Krepps, J.M. Relaxation Techniques. In StatPerls; Stat Perls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Klainin-Yobas, P.; Oo, W.N.; Yew, P.Y.S.; Lau, Y. Effects of relaxation interventions on depression and anxiety among older adults: A systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkova, E.; Zanesco, A.P.; Rogers, S.L.; Jha, A.P. Is resilience trainable? An initial study comparing mindfulness and relaxation training in firefighters. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 285, 112794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, R.S.; Sud, A. Management of Stress and Burnout of Police Personnel. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 34, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve, M.; Bruin, E.I.; de Rooij, F.; van Bögels, S.M. Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Police Officers. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1672–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S.B.; Tucker, R.P.; Greene, P.A.; Davidson, R.J.; Wampold, B.E.; Kearney, D.J.; Simpson, T.L. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 59, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spijkerman, M.; Pots, W.; Bohlmeijer, E. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: A review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grabovac, A.D.; Lau, M.A.; Willett, B.R. Mechanisms of Mindfulness: A Buddhist Psychological Model. Mindfulness 2011, 2, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Shapiro, S.L.; Swanick, S.; Roesch, S.C.; Mills, P.J.; Bell, I.; Schwartz, G.E.R. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 33, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Jazaieri, H.; Goldin, P.R. Mindfulness-based stress reduction effects on moral reasoning and decision making. J. Posit. Psychol. 2012, 7, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farb, N.; Segal, Z.V.; Mayberg, H.; Bean, J.; McKeon, D.; Fatima, Z.; Anderson, A.K. Attending to the present: Mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2007, 2, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsen, J.L.; Kvernenes, K.V.; Wiker, A.S.; Dundas, I. Mechanisms of mindfulness: Rumination and self-compassion. Nord. Psychol. 2016, 69, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, B.K.; Lazar, S.W.; Gard, T.; Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Vago, D.R.; Ott, U. How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lücke, C.; Braumandl, S.; Becker, B.; Moeller, S.; Custal, C.; Philipsen, A.; Müller, H.H. Effects of nature-based mindfulness training on resilience/symptom load in professionals with high work-related stress-levels: Findings from the WIN-Study. Ment. Illn. 2019, 11, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grossman, P.; Niemann, L.; Schmidt, S.; Walach, H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Focus Altern. Complement. Ther. 2010, 8, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Hunsinger, M.; Goerling, L.R.J.; Bowen, S.; Rogers, B.S.; Gross, C.R.; Dapolonia, E.; Pruessner, J.C. Mindfulness-based resilience training to reduce health risk, stress reactivity, and aggression among law enforcement officers: A feasibility and preliminary efficacy trial. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 264, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, L.B.; Hodgson, T.J.; Krikheli, L.; Soh, R.Y.; Armour, A.-R.; Singh, T.K.; Impiombato, C.G. Moral Injury, Spiritual Care and the Role of Chaplains: An Exploratory Scoping Review of Literature and Resources. J. Relig. Health 2016, 55, 1218–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, A.; Bergman, A.L.; Kaplan, J.; Goerling, R.J.; Christopher, M.S. A Qualitative Investigation of the Experience of Mindfulness Training Among Police Officers. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2019, 36, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, S.; Shand, F.; Lal, T.J.; Mott, B.; Bryant, R.A.; Harvey, S.B. Resilience@Work Mindfulness Program: Results From a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial With First Responders. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducar, D.M.; Penberthy, J.K.; Schorling, J.B.; Leavell, V.A.; Calland, J.F. Mindfulness for healthcare providers fosters professional quality of life and mindful attention among emergency medical technicians. EXPLORE 2020, 16, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J.; Omasta, M. Qualitative Research: Analyzing Life; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli, R.; Andres, E.; Mitchell, M.M.; Quirion, B.; Groll, D.; Adorjan, M.; Cassiano, M.S.; Shewmake, J.; Herzog-Evans, M.; Moran, D.; et al. CCWORK protocol: A longitudinal study of Canadian Correctional Workers’ Well-being, Organizations, Roles and Knowledge. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Willig, C.; Stainton Rogers, W. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli, R. “Risk It Out, Risk It Out”: Occupational and Organizational Stresses in Rural Policing. Police Q. 2018, 21, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, S.; Harris, P.R.; Cavanagh, K. Improving Employee Well-Being and Effectiveness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Web-Based Psychological Interventions Delivered in the Workplace. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Krätzig, G.P.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Neary, J.P.; Lix, L.M.; Fletcher, A.J.; Afifi, T.O.; Brunet, A.; Martin, R.; Hamelin, K.S.; et al. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Study: Protocol for a Prospective Investigation of Mental Health Risk and Resiliency Factors. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R.N.; Krätzig, G.P.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Neary, J.P.; Lix, L.M.; Fletcher, A.J.; Afifi, T.O.; Brunet, A.; Martin, R.; Hamelin, K.S.; et al. Assessing the impact of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Protocol and Emotional Resilience Skills Training (ERST) among Diverse Public Safety Personnel. 2022; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Yardley, S. Understanding Authentic Early Experience in Undergraduate Medical Education; Keele University: Newcastle, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Konyk, K.; Ricciardelli, R.; Taillieu, T.; Afifi, T.O.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N. Assessing Relative Stressors and Mental Disorders among Canadian Provincial Correctional Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grailey, K.E.; Murray, E.; Reader, T.; Brett, S.J. The presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: An evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Klink, J.J.; Blonk, R.W.; Schene, A.H.; Van Dijk, F.J. The benefits of interventions for work-related stress. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooper, C.L.; Cartwright, S. An intervention strategy for workplace stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 1997, 43, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, R.D., II. Leadership in the COVID-19 environment: Coping with uncertainty to support PSP mental health. JCSWB 2020, 5, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Donohue, R.; Eva, N. Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, S.; Luong, D.; McLean, R.; Szeto, A.; Dobson, K. Implementation, Uptake, and Culture Change: Results of a Key Informant Study of a Workplace Mental Health Training Program in Police Organizations in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64 (Suppl. S1), 30S–38S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lentz, L.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Malloy, D.C.; Anderson, G.S.; Beshai, S.; Ricciardelli, R.; Bremault-Phillips, S.; Carleton, R.N. A Qualitative Analysis of the Mental Health Training and Educational Needs of Firefighters, Paramedics, and Public Safety Communicators in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126972

Lentz L, Smith-MacDonald L, Malloy DC, Anderson GS, Beshai S, Ricciardelli R, Bremault-Phillips S, Carleton RN. A Qualitative Analysis of the Mental Health Training and Educational Needs of Firefighters, Paramedics, and Public Safety Communicators in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126972

Chicago/Turabian StyleLentz, Liana, Lorraine Smith-MacDonald, David C. Malloy, Gregory S. Anderson, Shadi Beshai, Rosemary Ricciardelli, Suzette Bremault-Phillips, and R. Nicholas Carleton. 2022. "A Qualitative Analysis of the Mental Health Training and Educational Needs of Firefighters, Paramedics, and Public Safety Communicators in Canada" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126972

APA StyleLentz, L., Smith-MacDonald, L., Malloy, D. C., Anderson, G. S., Beshai, S., Ricciardelli, R., Bremault-Phillips, S., & Carleton, R. N. (2022). A Qualitative Analysis of the Mental Health Training and Educational Needs of Firefighters, Paramedics, and Public Safety Communicators in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126972