Exploring Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use among Queer Adults during the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Qualitative Approach and Research Paradigm

2.2. Reflexivity and Researcher’s Characteristics

2.3. Ethical Issues Pertaining to Human Subjects

2.4. Context and Data Collection Methods

2.5. Data Collection, Instruments, and Technologies

- Screener

- Semi-Structured Interview Guide

- Smoking Questionnaire

- Memoing

- Technologies

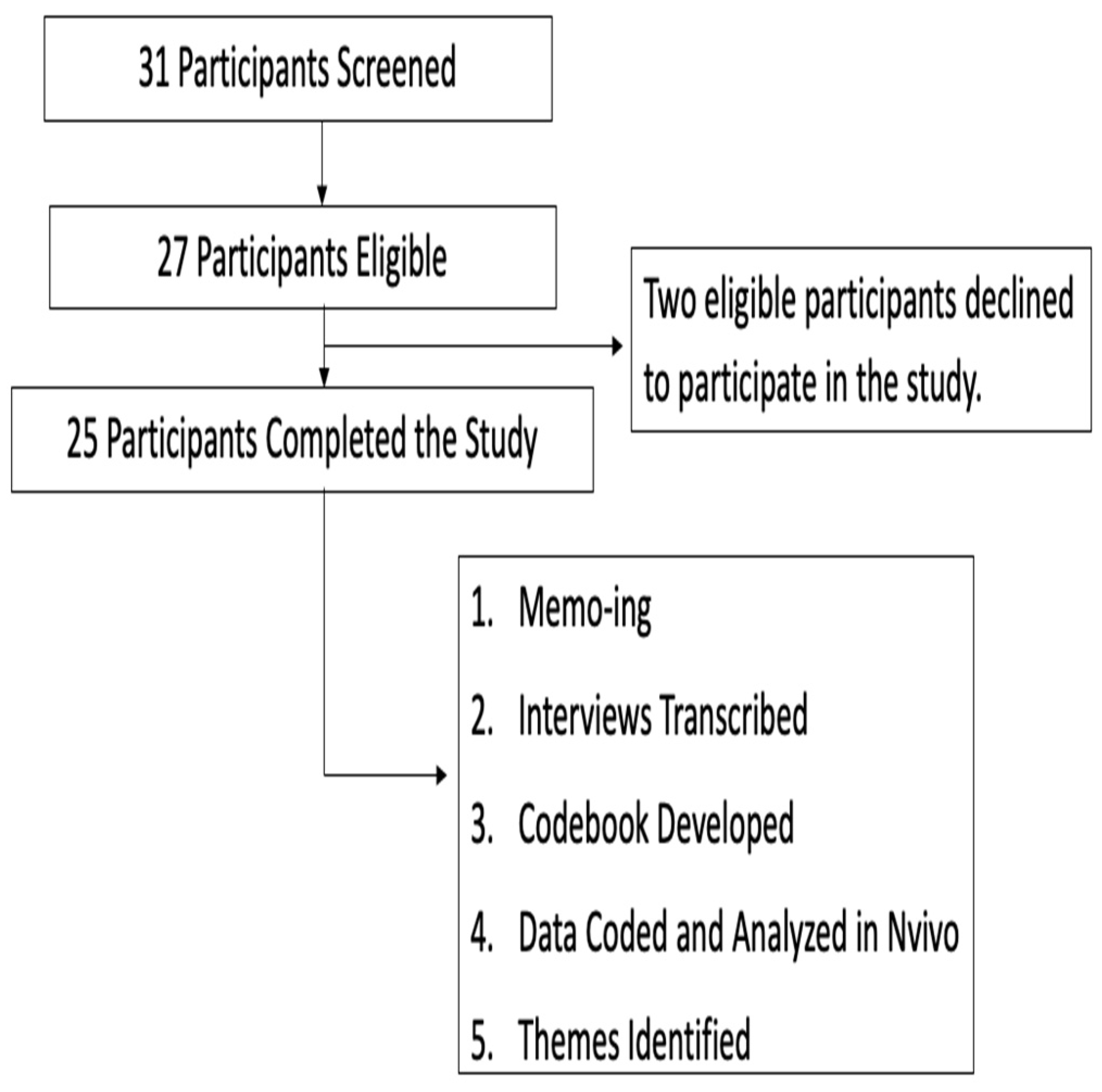

2.6. Qualitative Sampling

2.7. Data Processing

2.8. Data Analysis

Codebook

2.9. Inter-Coder Reliability

2.10. Establishing Rigor and Trustworthiness of Data

2.11. Qualitative Analysis

3. Findings

“Life is a transition right now. Like, I wake up every day and am like, what is going on? Like, I need to, you know, [should I] cancel my car insurance, do I get room furniture? I think my brain has been in this space a lot of the pandemic, it’s been in survival mode. What day is it? It’s Wednesday. Yeah, I’m already on my second pack, so it’s probably going to be like a three-pack week for me.”

“It has made me feel more urgency around smoking or at least more anxiety. I still haven’t been able to overcome the actual psychological addiction.”

“and at the beginning, I was freaking out. I needed a friend. I didn’t have my friends, [they] were like, busy as hell. And they were hiding from it too. And I was just; it was dark.”

3.1. Theme Two: Queer People Are Unfamiliar with Smoking Cessation

- Interviewer: So, what does cessation mean when I say smoking cessation?

- CH1005: Cessation…No, I don’t know cessation.

- Interviewer: So, the first thing I want to ask is, do you know what smoking cessation is?

- CH1011: Is that the feeling you get when you are smoking?

- Interviewer: So, cessation, not sensation. Smoking cessation.

- CH1011: Cessation. Oh. OK. So, I have to say. So, no, I don’t know what that is.

There’s not a lot of resources out there to help people stop smoking in the LGBT community. The only time you really hear the LGBT sector to tell people to stop smoking is when you are dealing with HIV. So, like that’s the only time I ever really see doctors, or anybody really, talk about smoking with the LGBT community.

3.2. Theme Three: Vaping and Smoking Are Used to Lessen Heightened Stress and Anxiety

Cigarettes is really a stress reliever for me personally. That’s mostly why I’m really smoking. You’ll see me smoking cigarettes, if I’m at work stressed, you’ll see me in the back vaping cause when I am angry upset.

Smoking is very bad. We know that. We see the commercials. We see the surgeon general warnings in the bottom of the cigarette packs. But do we consider them? No, because in that moment we are stressed, or we are going through something.

Especially when it comes down to like sex work in the LGBT community. It’s definitely, always something that helps keep that anxiety down while you on the. It’s…there’s a certain amount of anxiety with being LGBT and in space. Will, I be assaulted because I’m out here on the street? And I’m not passing. You know.

4. Discussion

- Strengths and Limitations

- Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Barker, M.; Scheele, J. Queer: A Graphic History; Icon Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bakersville, N.; Dash, D.; Shuh, A.; Wong, K.; Abramowicz, A.; Yessis, J.; Kennedy, R.D. Tobacco use cessation interventions for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth and young adults: A scoping review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 6, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Kim, Y.; Vera, L.; Emery, S. Electronic Cigarettes among Priority Populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wheldon, C.; Kaufman, A.; Kasza, K.; Moser, R. Tobacco Use among Adults by Sexual Orientation: Findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. LGBT Health 2018, 51, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gerend, M.; Newcomb, M.; Mustanski, B. Prevalence and correlates of smoking and e-cigarette use among young men who have sex with men and transgender women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 179, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, P.; Salazar, L.; Kota, K.; Pechacek, T. Prevalence of use and perceptions of risk of novel and other alternative tobacco products among sexual minority adults: Results from an online national survey, 2014–2015. Prev. Med. 2017, 104, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.; Safer, J. Increased Rates of Smoking Cessation Observed Among Transgender Women Receiving Hormone Treatment. Endocr. Pract. 2017, 23, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, S.; Matthews, A.; Lee, J.; Veliz, P.; Hughes, T.; Boyd, C. Tobacco Use and Sexual Orientation in a National Cross-sectional Study: Age, Race/Ethnicity, and Sexual Identity–Attraction Differences. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stall, R.; Greenwood, G.; Acree, M.; Paul, J.; Coates, T. Cigarette smoking among gay and bisexual men. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1875–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- LoSchiavo, C.; Acuna, N.; Halkitis, P. Evidence for the Confluence of Cigarette Smoking, Other Substance Use, and Psychosocial and Mental Health in a Sample of Urban Sexual Minority Young Adults: The P18 Cohort Study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2020, 55, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health. Path (Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health) Study—Home, 2021. National Institutes of Health. Available online: https://pathstudyinfo.nih.gov/ (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Jamal, A.; Agaku, I.T.; O’Connor, E.; King, B.A.; Kenemer, J.B.; Neff, L. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Transgender Equality. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey; National Center for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, K.; Zein, J.; Hatipoglu, U.; Attaway, A. Association of Smoking and Cumulative Pack-Year Exposure with COVID-19 Outcomes in the Cleveland Clinic COVID-19 Registry. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B. Theoretical Sensitivity; The Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich, A.; Tuval-Mashiach, R.; Zilber, T. Narrative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.; Poth, C. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elbardan, H.; Kholeif, A.O. An Interpretive Approach for Data Collection and Analysis. In Enterprise Resource Planning, Corporate Governance and Internal Auditing; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler-Kisber, L. Qualitative Inquiry: Thematic, Narrative and Arts-Informed Perspectives; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Dunya, A.A.; Lewando, H.G.; Blackburn, C. Issues of gender, reflexivity and positionality in the field of disability: Researching visual impairment in an Arab society. Qual. Soc. Work 2011, 10, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Skoldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty; NVivo 12 Software; Computer Program; NVivo: Melbourne, Australia, 2019.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Rance, N. How to use thematic analysis with interview data. In The Counselling & Psychotherapy Research Handbook; Vossler, A., Moller, N., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2014; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.; Norris, J.; White, D.; Moules, N. Thematic Analysis. Int J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 160940691773384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarel, K.E.; Mereish, E.H.; Manning, D.; Iwamoto, M.; Operario, D.; Nemoto, T. Minority stress, smoking patterns, and cessation attempts: Findings from a community-sample of transgender women in the San Francisco Bay Area. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia, J.; Vargas, N.; Clark, J.; Magaña Álvarez, M.; Nelons, D.; Parker, R. Social isolation and connectedness as determinants of well-being: Global evidence mapping focused on LGBTQ youth. Glob. Public Health 2019, 15, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruberg, S. An Effective Response to the Coronavirus Requires Targeted Assistance for LGBTQ People, 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2021. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbtq-rights/news/2020/04/09/482895 (accessed on 12 August 2021).

| First Code | Second Code | Third Code | Inclusion | Exclusion | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | Changing Behavior Coping with COVID-19 Threat Impact of COVID-19 on Smoking and Vaping Information About COVID-19 Knowledge of COVID-19 People at Risk for COVID-19 Sentiments About COVID-19 | Others in Community Self Social Distancing News and Social Media Social Networks Origin of COVID-19 | Any discussion of COVID-19. | No mention of changing behavior, coping, impact on smoking and vaping, COVID-19 information or knowledge, people at risk, and sentiments about COVID-19, | “I have cut down my smoking since the pandemic because of the droplets that could be coming out [when smoking] … I don’t want to be the ignorant person to infect someone.” |

| Preference over e-cigarettes vs. cigarettes | Culture of LGBT Community Desire to Appear More Masculine Social Norms | Any discussion about the differences between English COVID-19 search results compared to Spanish COVID-19 search results. Any discussion about why a participant prefers one type of product over another. | No mention about why a participant prefers one type of product over another. | “The thing about electronic cigarettes is that the electricity is just something different about it flowing through my body. One time I picked up an electronic cigarette and it really shocked me in my mouth … I’ll just stick to what I know.” | |

| Routine | Smoking Vaping | Any mention of routines related to smoking or vaping. | No mention of routines related to smoking or vaping. | “I only smoke more when I’m stressed, or if I’m drinking … The most cigarettes I have smoked in a day now is about five to six.” | |

| Smoking Cessation Treatment | Barriers to Smoking Cessation Treatment FDA Approved Medication Experience with Smoking Cessation Programs Knowledge of Smoking Cessation LGBT Smoking Cessation Treatment Steps to Quitting | NJ Quit Line Quit Center | Any mention of smoking cessation, barriers to quitting, experience with smoking cessation programs. | No mention of smoking cessation, barriers to quitting, experience with smoking cessation programs. | “I had a roommate that had a heavy smoking problem. He actually got a podcast of self-help to kind of talk him through not smoking. He said those are really helpful, too. So, if I was trying to do something long term, I might incorporate something like that as well. I think that gum would be something I would use.” |

| Smoking History | Benefits of Smoking Provider Discussion Reasons for Smoking | Any mention about benefits of smoking, provider discussing smoking behavior with study participant, motivations for smoking | No mention of benefits of smoking, provider discussing smoking behavior with study participant, motivations for smoking | “I remember vaguely my first time I actually smoked a cigarette. I was in high school. I think I was about 15 or 16. The young lady who lived next door to me, she was a smoker. So I would see her smoke and I thought it was cool.” | |

| Smoking or Vaping Identity | Any mention of tobacco smoking and vaping as part of their self-identity, culture, motivations, etc. | No mention of cigarette smoking and vaping as part their self-identity, culture, motivations, etc. | “I think that I am a social smoker. Although, even when I’m not in the social environment, if I do get by myself every now and then, I’ll have one by myself.” | ||

| Social Determinants of Health | Health Problems Minority Stress Stigma and Discrimination | Any discussion about health problems, minority stress, and stigma and discrimination. | No mention of health problems, minority stress, and stigma and discrimination. | “…most of the issues come from people dealing with housing, or dealing with their own personal issues that they have … they’re looking for a way out. Drugs, cigarettes, all of these things are their way out.” | |

| Thoughts on Vaping Crisis | Any mention of vaping crisis. | No mention of vaping crisis. | “I stopped smoking vapes after hearing about everybody with the lung diseases…” | ||

| Tobacco Products | Money Spent | Any discussion about tobacco products currently being used, previously used, and how much is spent acquiring tobacco products. | No mention of tobacco products currently being used, previously used, and how much is spent acquiring tobacco products. | “I tend to order a lot of cigars. I order in bulk…I would say probably a couple of packs a week.” | |

| Vaping History | Benefits of VapingMoney Spent on e-cigs. Reasons for Vaping Risk of Vaping Vaping Devise | Any discussion about previous vaping behavior, perceived benefits from vaping, money used to acquire vaping products, motivations for vaping, perceived risks of vaping, and any conversations about vaping device. | No mention of previous vaping behavior, perceived benefits from vaping, money used to acquire vaping products, motivations for vaping, perceived risks of vaping, and any conversations about vaping device. | “First time I tried to vape was in D.C. It was OK. It really didn’t work for me because of the simple fact that it’s not as strong…” | |

| Drug Use | cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing e-cigarette or other substance | Any discussions about vaping cannabis, THC or other substances in vaping device | No mention of cannabis, THC or other substances in vaping device | “…once they were able to start putting THC into [vapes] that’s why everybody wanted to vape.” |

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 9 (36.0) |

| 25–29 | 7 (28.0) |

| 30–34 | 9 (36.0) |

| Race | |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 1 (4.0) |

| Asian | 2 (8.0) |

| Black or African American | 13 (52.0) |

| White | 8 (32.0) |

| Two or More Races | 1 (4.0) |

| Are you Hispanic or Latino | |

| Yes | 2 (8.0) |

| No | 23 (92.0) |

| Highest Educational Attainment | |

| High School or GED | 4 (16.0) |

| Some College/Technical School | 10 (40.0) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 8 (32.0) |

| Graduate Degree | 3 (12.0) |

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Current Gender | |

| Female | 5 (20.0) |

| Male | 13 (52.0) |

| Transgender | 3 (12.0) |

| Gender non-binary | 4 (16.0) |

| Sexuality | |

| Bisexual | 7 (28.0) |

| Gay | 10 (40.0) |

| Heterosexual | 1 (4.0) |

| Lesbian | 1 (4.0) |

| Pansexual | 2 (8.0) |

| Queer | 4 (16.0) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 13 (52.0) |

| Unemployed | 6 (24.0) |

| Homemaker/caretaker | 1 (4.0) |

| Student | 5 (20.0) |

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Tobacco Products Used a | |

| Cigarettes | 20 (80.0) |

| Little Cigar with filter | 7 (28.0) |

| Little Cigar without filter | 3 (12.0) |

| Large Cigar | 2 (8.0) |

| Cigarillos | 6 (24.0) |

| Electronic devices | 14 (56.0) |

| Hookah | 11 (44.0) |

| Cigarettes Smoked Per Day b | |

| 10 or less | 20 (80.0) |

| 11–20 | 4 (16.0) |

| 21–30 | 0 (0) |

| 31 or more | 0 (0) |

| Time to first Cigarette After Waking Up b | |

| More than 60 min | 8 (32.0) |

| 31–60 min | 1 (4.0) |

| 5–30 min | 8 (32.0) |

| Less than 5 min | 4 (16.0) |

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Have you ever used an e-cigarette? | |

| Yes | 23 (92.0) |

| No | 2 (8.0) |

| Do you use e-cigarettes to quit tobacco? a | |

| Yes | 11 (44.0) |

| No | 12 (48.0) |

| How many pods/cartridges do you use per day? a | |

| Zero | 1 (4.8) |

| Less than one | 2 (9.5) |

| One | 12 (57.1) |

| Between one and two | 1 (4.8) |

| Two | 1 (4.8) |

| More than two | 1 (4.8) |

| Unknown | 3 (14.3) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valera, P.; Owens, M.; Malarkey, S.; Acuna, N. Exploring Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use among Queer Adults during the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412919

Valera P, Owens M, Malarkey S, Acuna N. Exploring Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use among Queer Adults during the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):12919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412919

Chicago/Turabian StyleValera, Pamela, Madelyn Owens, Sarah Malarkey, and Nicholas Acuna. 2021. "Exploring Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use among Queer Adults during the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 12919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412919

APA StyleValera, P., Owens, M., Malarkey, S., & Acuna, N. (2021). Exploring Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use among Queer Adults during the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 12919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412919