Exploration of Psychological Resilience during a 25-Day Endurance Challenge in an Extreme Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Research Design and Philosophical Underpinnings

2.2. Challenge Context

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection Methods

2.4.1. Video Diaries

2.4.2. Focus Groups

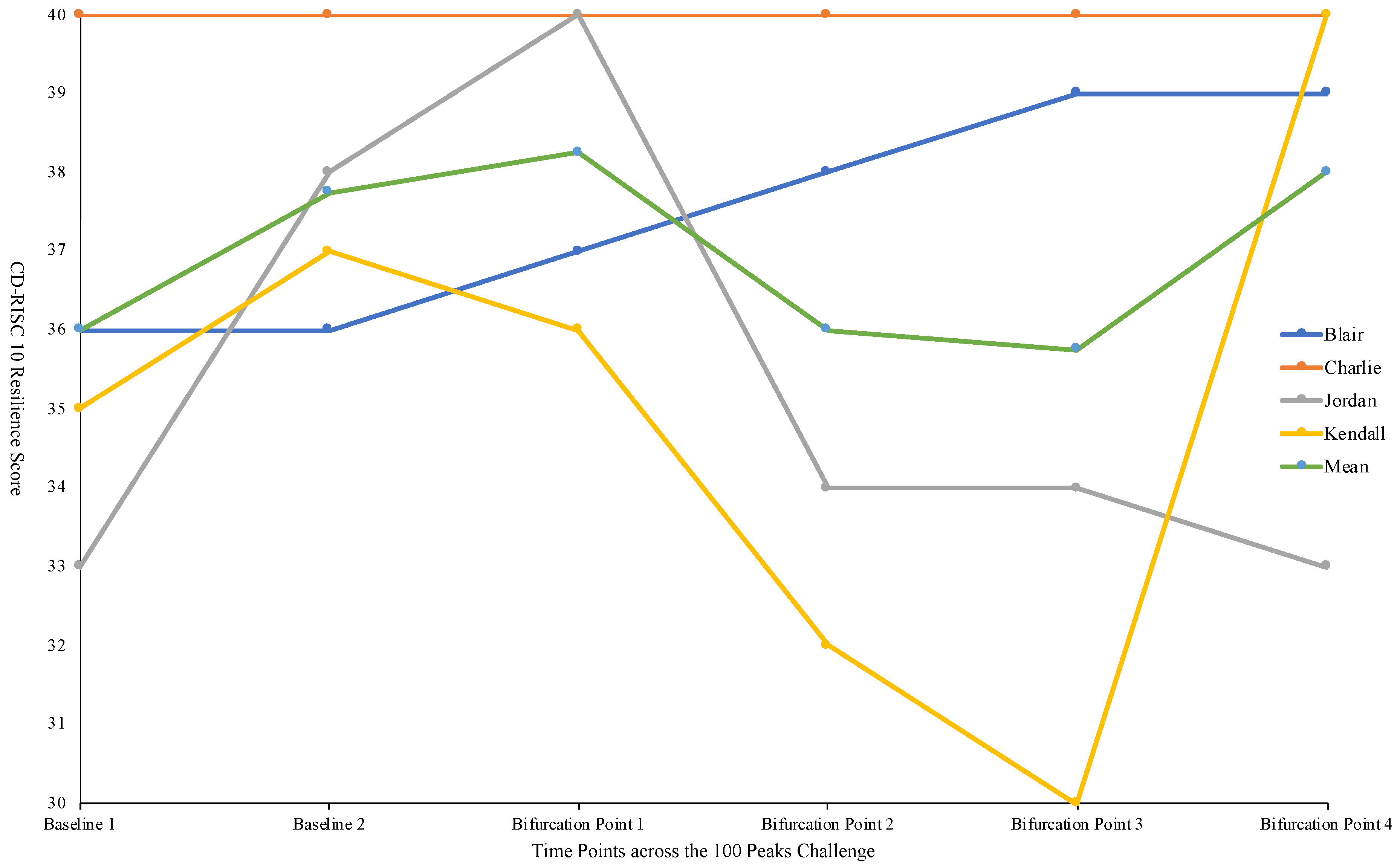

2.4.3. The 10-Item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC10)

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Methodological Rigour

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of Stressors during the Challenge

“Some serious terrain challenges, makes you question the choices, choices you are making. Obviously, the heat today, apparently it was the hottest place in the UK today and we certainly felt it. So, obviously, that adds some real complexity to being out on the hills.”

“It was a very hot day and a very tough day…the first few hills going, I could feel my quads and my calves but I expected that so I went through and we just managed through the day.”

3.1.1. Cluster Effect

“Today, it’s just knowing what’s required in these sorts of conditions to ensure you are safe, the group, the people you are with, the team are safe, are they doing the right things…with the cumulative effect of what we’re doing.”

“But I think obviously we’ve had it difficult, the support team have had it difficult because it’s been there are challenges within the challenge no one anticipated that we would have to deal with the midge infestation that we had or well just the biblical efforts of the weather. And of course that puts a strain on things. It’s natural you’re isolated because you can’t actually sit and be a complete community cause the only shelter is a piece of polythene. We’re in each other’s pockets 24 h a day, 7 days a week with people that you’ve not lived with spent time with and we’ve all got our own idiosyncrasies. We’ve all got our own ways of doing things and at time yeah you do lose it. You don’t lose your temper or you get moody or whatever and take yourself away from it but then in the end you’ve just gotta come back and carry on.”

3.1.2. Different Stages and Bifurcation Points

“It is an unusual environment to be in and you all get tired you all have good days and bad days and you get through that. There’s not a lot of choice you just focus on the next day but there’s always something coming next or you have to get ready or there’s like people asking questions or prepare for the next day it’s all go, go, go. And I think it’s for everyone it’s for the support team it’s also for us the same…Yeah so we didn’t really have a lot of time to actually chill and relax and let things sink in because we had long days and we had to get ready for the next one and think about the next day so we didn’t have a lot of like downtime just to chill and just sit as a team. And also because of the midges and the weather we kinda stuck in our tents sometimes so yeah.”

3.1.3. Start of the Cluster Effect

“Sure like it’s if you go to find the cycling and the climbing the peaks like Jordan has said as well and the weather and the midges and just everything else even like transition day packing up and things like that those are challenges on their own apart from the cycling and you’ve got challenges also getting along with the team and making sure everything work well the support team those are separate challenges on top of what we do already so and yeah.”

“The day went pretty well. Coming back to base camp, talking to the [support team] they have had a nightmare setting up the base camp. The midges here at the moment are absolute hell. That is, one of the hardest challenges is dealing with the midges.”

“I’ve found some situations difficult to deal with purely because I don’t understand the mentality of certain individuals that they make, and, because of the nature of this challenge. Because of the nature of the physicality of it and everyone is getting tired the demands are great and conditions aren’t ideal. Small things become big things.”

“And because we had the transition before. It was a late start which wasn’t ideal but it is what it is so we cracked on with the TAB and immediately found that the ground was quite tough.”

3.2. Exploration of Resilience

Challenge Mindset

“It was a big challenge for me yesterday. I haven’t covered anywhere near that distance…another challenging day, but the hills are why I am here. The cycling isn’t my thing. It’s something I’m just doing [to get back in the hills].”

“The main challenge was the terrain for us from that point of view, absolutely horrendous again. It is so hard to explain what you have to go through to get to the top of the mountains.”

“In comparison to what this time of year means to me, this challenge isn’t anywhere near as tough as what this period of time means. So again, being away from home, maybe that’s more of a challenge than this is.”

“The terrain, its actually very very difficult to make people understand unless you’re doing these routes how demanding actually those trails are. So, that’s a challenge and the only way you can deal with that challenge is putting one foot in front of the other…I don’t stop. I keep going. I keep focused on what we are trying to achieved.”

“Mentally its draining purely because every single step we’re taking, especially on the ridges, every single step you’re taking you’re having to constantly watch your footing and that is taxing.”

“We decided to take a vote on it and initially 3 people wanted to go forward and along the ridge and 2 decided it was, probably too risky and I was one who said that is wasn’t as bad as it looked, there was a safe way off…So, I think we made the right call.”

“I think we just sort of bounce off each other a bit, don’t we? And, you know, try and have a bit of a laugh, if you see someone down, just try and pick them up a bit, you know, sort of we’re always having a laugh and a joke and, you know, it seems to keep everyone’s morale up… it probably releases…tension is not the right word, but I think it just, a little bit of humour goes a long, long way. I think when you’re faced with the challenges that we’re obviously faced with day in, day out, irrespective of the challenge itself. Obviously in addition to all the personal challenges that people are facing, it just sort of, it’s a smile, a bit of humour can make the day a lot, lot brighter. And obviously it needs to because the days are long and they’re only going to get longer, and the challenges are only going to get more and more arduous as we go on.”

“Just having that focus to get up each one and again it was just…and yeah we have a right laugh when we’re out it’s a bit ridiculous really some of the things that we’ve done. Look at me. And looking across, I mean, we were on… We were going up one mountain it was the worst one we’ve been and I looked across to Blair and I mean it was literally like that [makes hand gesture about the slope] but it was all just loose stone and shingle and slate and everything else so every time you moved the whole mountain just moved and I’ve look across to them and we were just laughing at each other and I think if you haven’t got that sense of humour you’d kind of knock it on the head.”

“We actually had a bit of a laugh, just I didn’t really chip in much, but, you know, we all had a laugh…There was a bit of a challenge yesterday and the way I kind of deal with it is to just laugh about it.”

“All of us really is I would say sorting the base camp out. Within a couple of days they got it running like clockwork for us…So really the support team, at the moment the support team are what’s making this happen for us. I mean we…well, for me, we’ve got the easy job, we’re sort of doing what we love doing…it’s such a hard physical challenge, it is easy for us because we’re not having to come home and cook our tea, wash our clothes, get everything ready, these guys are doing it all for us. So, although the days are long and that, it’s brilliant, it really is.”

“They’ve been around, they’ve been terrible the midges. If it’s not pissing down with rain and freezing cold then the midges are out but it’s like I’ve said for us we’re up in the mountains or on our bikes so we do get away from it for a long period of time these guys they’re never away from it. The weather’s either shit for ‘em or they’re getting bit too… We come back here and they’ve got nets over their faces and they’re still cooking and getting stuff ready, washing, drying it can’t be easy and like I say it’s not a job… I’d much rather be climbing mountains all day than doing all that.”

“And on the top of the mountain we had [Partial] sitting there waiting for us with a carrier bag full of snow, stuffed with Trooper [bottled beer] in it. And the bloke had driven 500 miles just to be there and come and TAB with us, which is massive.”

“[Partial] wasn’t as fit as I was, kind of, left with them, and I encouraged them. I looked after them and I looked after them and the [other challenge team members] went off. So, I that made me pretty pissed off to be honest.”

“I mean a prime example was like yesterday, we was in the mountains for a good while. And the conditions were rubbish, you know, rain, wind, couldn’t really see a lot in front of you. And we was up there like yesterday, what, eight/nine hours. You know, and then we come back down and [Support Team Member] is there with a hot chocolate.

He offered us chocolate bars.

Just that, it’s a real sort of morale lifter.

Just, that it’s simple things like that, it really is simple things. When you’ve had a hard day, the thought of actually coming back and seeing that you’ve got something hot and steaming and sweet.”

“Everybody’s physically tired, mentally tired and I mean we had a lot of days where you’re not so much the stuff that we was doing was possibly physically demanding but it was mentally demanding.”

“You do face challenges like every day actually. When you come onto the hills, you’ve got mud, slime and yeah, like with communication as well. At first you need to, you know, get used to the people. See how they, you know, work and things like that. And the longer the challenge goes on, you know, the better it gets, you get to know each other better. But to pick out a specific challenge, it’s quite hard, because every day, you know, every mile is a challenge, you know, sometimes you’ve got sore legs on the bike. Well, you just have to push through and, you know, work together and help each other.”

“You’ve got to accept at the end of the day individuals have different personality traits and it’s trying to get used to how people operate. You’ve gotta then learn how to try and instil the best behaviour part of everybody to ensure that you get where you need to be. And I think with a challenge like this it’s probably very difficult because although it’s a seemingly long period of time it’s not really in the grand scheme of things. 25 days isn’t long to spend with people that you’ve probably never spent 25 days with before to completely understand them as individuals and obviously that takes a long time to work out the kinks but it’s the getting there slowly but surely.”

“Probably not spent that amount of time in close proximity with these people before and there’s always gonna be the odd tension that’s gonna spring up from time to time it’s just a case of if that arises putting the team first and thinking “I’ve gotta work with all these people” and getting on with it for the sake of the main goal.”

4. General Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Research

4.3. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheerin, C.M.; Stratton, K.J.; Amstadter, A.B.; The Va Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness The VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, Clinical Center (MIRECC) Workgroup; McDonald, S.D. Exploring resilience models in a sample of combat-exposed military service members and veterans: A comparison and commentary. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 9, 1486121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, N.; Pagano, K. Furthering the discussion on the use of dynamical systems theory for investigating resilience in sport. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2018, 7, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, E.; Martin, P. Extreme: Why Some People Thrive at the Limits; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological Resilience: A Review and Critique of Definitions, Concepts, and Theory. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.; O’Shea, D.; MacIntyre, T. Stressing the relevance of resilience: A systematic review of resilience across the domains of sport and work. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 12, 70–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Fletcher, D. Ordinary magic, extraordinary performance: Psychological resilience and thriving in high achievers. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2014, 3, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Fletcher, D. Psychological resilience in sport performers: A review of stressors and protective factors. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1419–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, M.A. Resilience in ecosystemic context: Evolution of the concept. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 2001, 71, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.T.; Beckham, J.C.; Youssef, N.; Elbogen, E.B. Alcohol misuse and psychological resilience among U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan era veterans. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Implications of Resilience Concepts for Scientific Understanding. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Motti-Stefanidi, F. Multisystem Resilience for Children and Youth in Disaster: Reflections in the Context of COVID-19. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2020, 1, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Burton, C.L. Regulatory Flexibility. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Mental fortitude training: An evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. J. Sport Psychol. Action 2016, 7, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, F. Resilience: How We Find New Strength at Times of Stress; Hatherleigh Press: Hobart, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, C.; Sommerfield, A.; Von Ungern-Sternberg, B.S. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Landi, G.; Boccolini, G.; Furlani, A.; Grandi, S.; Tossani, E. The moderating roles of psychological flexibility and inflexibility on the mental health impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Italy. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 17, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick, E.; DiCorcia, J.A. The Everyday Stress Resilience Hypothesis: A Reparatory Sensitivity and the Development of Coping and Resilience. Child. Aust. 2015, 40, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 857–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, N.; Vealey, R.S. “Bouncing Back” from Adversity: Athletes’ Experiences of Resilience. Sport Psychol. 2008, 22, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandal, G.M.; Leon, G.R.; Palinkas, L. Human challenges in polar and space environments. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio Technol. 2006, 5, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, G.R.; List, N.; Magor, G. Personal Experiences and Team Effectiveness During a Commemorative Trek in the High Arctic. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjærgaard, A.; Leon, G.R.; Fink, B.A. Personal Challenges, Communication Processes, and Team Effectiveness in Military Special Patrol Teams Operating in a Polar Environment. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 644–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Kinnafick, F.; Cooley, S.J.; Sandal, G.M. Reported Growth Following Mountaineering Expeditions: The Role of Personality and Perceived Stress. Environ. Behav. 2016, 49, 933–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaergaard, A.; Leon, G.R.; Venables, N.C. The “Right Stuff” for a Solo Sailboat Circumnavigation of the Globe. Environ. Behav. 2014, 47, 1147–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, A.; Yoshino, A. The influence of short-term adventure-based experiences on levels of resilience. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2011, 11, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, T. A 20-year retrospective study of the impact of expeditions on Japanese participants. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2010, 10, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, J. Psychological factors in exceptional, extreme and torturous environments. Extrem. Physiol. Med. 2016, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.; Barrett, E.C. Psychology, extreme environments, and counter-terrorism operations. Behav. Sci. Terror. Politi. Aggress. 2018, 11, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.; Palmer, S. A review of stress, coping and positive adjustment to the challenges of working in Antarctica. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2003, 41, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.; Ewert, A.; Chang, Y. Multiple Methods for Identifying Outcomes of a High Challenge Adventure Activity. J. Exp. Educ. 2016, 39, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Relations Between Self-Reported and Linguistic Monitoring Assessments of Affective Experience in an Extreme Environment. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2018, 29, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, N.; Gonzalez, S.P. Psychological resilience in sport: A review of the literature and implications for research and practice. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 13, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Butt, J.; Sarkar, M. Overcoming Performance Slumps: Psychological Resilience in Expert Cricket Batsmen. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2020, 32, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.; Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Understanding team resilience in the world’s best athletes: A case study of a rugby union World Cup winning team. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Hilton, N.K. Psychological Resilience in Olympic Medal–Winning Coaches: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study. Int. Sport Coach. J. 2020, 7, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health from Process to Product; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Poucher, Z.A.; Tamminen, K.A.; Caron, J.G.; Sweet, S.N. Thinking through and designing qualitative research studies: A focused mapping review of 30 years of qualitative research in sport psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 13, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezalla, A.E.; Pettigrew, J.; Miller-Day, M. Researching the researcher-as-instrument: An exercise in interviewer self-reflexivity. Qual. Res. 2012, 12, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M. Critical Analysis of Strategies for Determining Rigor in Qualitative Inquiry. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, V.; Smith, J. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A. Evaluating the contribution of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 5, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, L.K. Longitudinal qualitative research and interpretative phenomenological analysis: Philosophical connections and practical considerations. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2017, 14, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelgrove, S.R. Conducting qualitative longitudinal research using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Nurse Res. 2014, 22, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snelgrove, S.; Edwards, S.; Liossi, C. A longitudinal study of patients’ experiences of chronic low back pain using interpretative phenomenological analysis: Changes and consistencies. Psychol. Health 2013, 28, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, P.; Kampman, H. Exploring the psychology of extended-period expeditionary adventurers: Going knowingly into the unknown. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 46, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; Smith, J.A., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2003; pp. 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dentry-Travis, S.J. Conducting Interviews in Extreme Environments: Perceptions of Mental and Physical Durability During a High-Altitude Antarctic Expedition. In Conducting Interviews in Extreme Environments: Perceptions of Mental and Physical Durability During a High-Altitude Antarctic Expedition; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. Qualitative Contributions to Resilience Research. Qual. Soc. Work. Res. Pract. 2003, 2, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, P.C.; Clay, G.; Coussens, A.H.; Bird, M.D.; Henderson, H. ‘We are fighting a tide that keeps coming against us’: A mixed method exploration of stressors in an English county police force. Police Pract. Res. 2021, 22, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.C. Developing mixed methods research in sport and exercise psychology: Critical reflections on five points of controversy. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 100 Peaks. Available online: https://the100peaks.com/the-100-peaks (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Treweek, A.J.; Tipton, M.J.; Milligan, G. Development of a physical employment standard for a branch of the UK military. Ergon. 2019, 62, 1572–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenan, M.S.; Lafiandra, M.E.; Ortega, S.V. The Effect of Soldier Marching, Rucksack Load, and Heart Rate on Marksmanship. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2016, 59, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Brown, J.M.; Bray, R.M.; Goodell, E.M.A.; Olmsted, K.R.; Adler, A.B. Unit Cohesion, Resilience, and Mental Health of Soldiers in Basic Combat Training. Mil. Psychol. 2016, 28, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, S.J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Cumming, J.; Novakovic, E.G.; Burns, V.E. Introducing the use of a semi-structured video diary room to investigate students’ learning experiences during an outdoor adventure education groupwork skills course. High. Educ. 2014, 67, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cherrington, J.; Watson, B. Shooting a diary, not just a hoop: Using video diaries to explore the embodied everyday contexts of a university basketball team. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. 2010, 2, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P. Focus Group Methodology: Principles and Practice; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P.; Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Defining and characterizing team resilience in elite sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.P.; Detling, N.; Galli, N.A. Case studies of developing resilience in elite sport: Applying theory to guide interventions. J. Sport Psychol. Action 2016, 7, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucciardi, D.; Jackson, B.; Coulter, T.; Mallett, C.J. The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Dimensionality and age-related measurement invariance with Australian cricketers. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangallo, A.; Zibarras, L.; Lewis, R.; Flaxman, P. Resilience through the lens of interactionism: A systematic review. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Fonseca, J.; Silva, L.D.M.; Davies, G.; Morgan, K.; Mesquita, I. The promise and problems of video diaries: Building on current research. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2014, 7, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C. Embodied Transcription: A Creative Method for Using Voice-Recognition Software. Qual. Rep. 2014, 15, 1227–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, M.-J.; Kirkby, J. Taming the ‘Dragon’: Using voice recognition software for transcription in disability research within sport and exercise psychology. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2013, 5, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, L. Doing interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Analysing Qualitative Data in Psychology; Lyons, E., Coyle, A., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2007; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.; McGannon, K. Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 11, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizza, I.E.; Farr, J.; Smith, J.A. Achieving excellence in interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): Four markers of high quality. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, J.; Nizza, I.E. Longitudinal Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (LIPA): A review of studies and methodological considerations. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2018, 16, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. Generalizability in qualitative research: Misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2018, 10, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemignani, M. Toward a critical reflexivity in qualitative inquiry: Relational and posthumanist reflections on realism, researcher’s centrality, and representationalism in reflexivity. Qual. Psychol. 2017, 4, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, L. Engaging Phenomenological Analysis. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2014, 11, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallerio, F.; Wadey, R.; Wagstaff, C.R.D. Member reflections with elite coaches and gymnasts: Looking back to look forward. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2020, 12, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bonanno, G.A. Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S51–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzey, D. Cognitive and Psychomotor Performance. In Breakthroughs in Space Life Science Research; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sandal, G.M. Psychological Resilience. In Space Safety and Human Performance; Sgobba, T., Kankl, B.G., Clervoy, F., Sandal, G.M., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 183–237. [Google Scholar]

- Nindl, B.C.; Billing, D.C.; Drain, J.R.; Beckner, M.E.; Greeves, J.; Groeller, H.; Teien, H.K.; Marcora, S.; Moffitt, A.; Reilly, T.; et al. Perspectives on resilience for military readiness and preparedness: Report of an international military physiology roundtable. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankl, V. Man’s Search for Meaning; Rider: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, M.H. Humor, stress, and coping strategies. Humor-Int. J. Humor Res. 2002, 15, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Kale, A.; Yuan, Z. Is humor the best medicine? The buffering effect of coping humor on traumatic stressors in firefighters. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brcic, J.; Suedfeld, P.; Johnson, P.; Huynh, T.; Gushin, V. Humor as a coping strategy in spaceflight. Acta Astronaut. 2018, 152, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beames, S. Critical elements of an expedition experience. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2004, 4, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCorcia, J.A.; Tronick, E. Quotidian resilience: Exploring mechanisms that drive resilience from a perspective of everyday stress and coping. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Identification of Stressors | |

|---|---|

| Significant Stressors | Personal Administration Errors |

| Unpredictable Disruptive Incidents | |

| Everyday Stressors | |

| Cluster Effect | |

| The Start of the Cluster Effect | |

| Different Stages and Bifurcation Points | |

| Exploration of Resilience | |

|---|---|

| Challenge Mindset | Acceptance |

| Putting One Foot in From of the Other | |

| Humour | |

| The Complexity of Social Support | |

| Interpersonal Differences | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harrison, D.; Sarkar, M.; Saward, C.; Sunderland, C. Exploration of Psychological Resilience during a 25-Day Endurance Challenge in an Extreme Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312707

Harrison D, Sarkar M, Saward C, Sunderland C. Exploration of Psychological Resilience during a 25-Day Endurance Challenge in an Extreme Environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312707

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarrison, David, Mustafa Sarkar, Chris Saward, and Caroline Sunderland. 2021. "Exploration of Psychological Resilience during a 25-Day Endurance Challenge in an Extreme Environment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312707

APA StyleHarrison, D., Sarkar, M., Saward, C., & Sunderland, C. (2021). Exploration of Psychological Resilience during a 25-Day Endurance Challenge in an Extreme Environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312707