1. Introduction

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in young people is rising globally with consequences for long-term health [

1,

2]. There is strong evidence that marketing, including advertising, for unhealthy food (high in saturated fat, salt or sugar: HFSS) contributes to overweight and obesity [

2,

3,

4], and a consensus is increasingly developing that the persuasive actions marketers engage in, to influence children’s (including adolescents’) behaviour, infringes children’s rights, including rights to health and not to be exploited [

5,

6]. However, much of the existing evidence for young people’s interactions with marketing and its effects has been generated for television and for younger children rather than adolescents [

3]. Yet young people spend increasing amounts of time engaged in online activities [

7,

8,

9].

Advertisers have extensive digital media presence including on social and media-sharing platforms where they promote products and brands as exciting and interactive [

6,

10,

11]. In digital media (as in traditional media), most food and beverage advertising is for unhealthy items: reports indicate 65%–80% of food advertising online is for HFSS products or brands associated with these foods [

12,

13,

14]. Furthermore, as food and beverage companies have extensive followings online, including among teens, their activities reach large audiences [

15]; the food brands with the greatest potential reach amongst teens are almost all brands with many or mostly unhealthy products in their portfolios [

16]. Adolescents are at risk of exposure to unhealthy food advertising because of their very high levels of Internet and social media usage. Diary, screen-recording and avatar studies indicate high levels of exposure [

12,

14,

17]. However, evidence for how young people engage with and respond to food advertising in digital media remains limited [

4,

6].

Although adolescents understand the persuasive intent of advertising, they are hypothesized to lack the motivation and ability to defend against its effects [

6,

18,

19]. Alcohol and tobacco advertising research suggests that moderation of advertising influence is dependent on viewers’ self-control [

20], a quality often still developing in adolescence. Research also points to hypersensitivity to reward in the adolescent years [

21]. Furthermore, specific features of digital media advertising may reduce cognitive defences to effects of marketing [

22]. Brands on social media regularly create interactive content not present in traditional media [

6,

11] which is highly integrated and often difficult to distinguish from non-marketing content [

23]. Online marketing also engages with users’ social networks, inserting themselves into adolescents’ social lives by presenting brands as ‘liked’ by friends and encouraging users to interact with brands as if they were individuals [

24,

25]. Thus, despite being advertising-literate, adolescents are likely to be vulnerable to food advertising.

1.1. Adolescents and Peers Online

Adolescents are particularly susceptible to social effects as they are motivated to interact with their peers [

26] and, in social media, to connect with and view friends’ profiles [

8]. Sharing social media content with friends serves a number of psychological incentives including self-expression and connecting with others [

27]. Adolescents give careful consideration to the image they present online, conveying a socially acceptable self-image to others by sharing content popular with friends [

28]. They place a great importance on peer norms and acceptance [

29], identifying with their friends and generally with those of the same gender [

30]. As social media sites allow users to connect with friends extensively [

31], they are a powerful means for transmitting norms, ideas and behaviours.

The normative model of eating indicates that eating is directed by situational norms, the eating behaviours of those present, and their social approval [

32]. Compared to preadolescents, teen peers exert more influence on food choice [

33,

34]: adolescents describe eating more unhealthy foods at school and with their friends than at home [

35] and exchanges with peers stimulate unhealthy eating behaviours [

36,

37]: teens attempt to manage peers’ impressions of them through altering eating habits in order to meet what they perceive as the social norm [

38,

39]. Presenting or ‘sharing’ pictures of food is a popular activity in social media [

40]. Peers are often thought to be more trustworthy than brands, and effects of online advertising are reported to be amplified when this is endorsed by a peer [

6,

41].

1.2. Celebrities

Social media allows users to interact not only with peers but view content posted by celebrities, who have role model status for young people [

42]. Social media users can gain the illusion of a personal connection with celebrities, following updates in a similar way that they do from friends and family and with whom they may develop ‘parasocial’ relationships: for example, a study of fans’ interaction with the reality television personality Kim Kardashian’s online persona found they felt they were in a reciprocal, parasocial friendship [

43,

44]. Sports stars, music celebrities and online influencers regularly promote unhealthy food; up to one quarter of endorsements by music celebrities and athletes are promotions of HFSS foods and beverages [

45,

46], which can lead to increased consumption [

47], often over healthier options [

48].

1.3. Recall, Recognition and Attention

The food advertising hierarchy of effects framework [

49] indicates that brand recall and recognition influence brand attitudes and eating behaviours, which lead to weight-related outcomes.

After advertising is viewed, it is retained in memory either explicitly (i.e., with conscious awareness) or implicitly [

50,

51]; and greater cognitive processing leads to easier recall [

52].

As media use increases, however, and multiple-device viewing becomes the norm [

7], it is reported that only 10% of all online advertisements are attended to [

53] so it is important, rather than identifying the mere presence of marketing content in social media, to identify what is attended to. Eye-tracking is a widely used index of attentional selection [

54] with longer and greater number of fixations associated with a more favourable opinion of the item [

55]. Attention can lead to altered eating patterns in young people [

56], and unhealthy food items attract greater interest than healthy and non-food items [

57,

58]. Social context is thought to play a significant role in ad recall, awareness and intent to purchase [

41] but evidence is limited, particularly so for social context in the online space.

This study aimed to determine adolescents’ responses to healthy, unhealthy, and non-food advertising. The food advertising hierarchy of effects framework [

49] synthesizes multiple theories and strands of empirical research to conclude that repeated exposure to advertising triggers recall and recognition, positive attitudes and normalization of promoted products, and subsequently, when exposed to relevant cues, intent to purchase or consume. Theories of social norms of eating can be nested within this model and these indicate that social groups establish norms for appropriate foods [

59]. In social media, social norms of food are displayed, disseminated and reinforced, as young people do not just

see food advertising but can also choose to

share it with their ‘imagined audience’ of peers [

27], and in turn can also

assess their peers based on such content. Thus, the identity and self-presentation-based normative goals of the adolescent years [

27] are interwoven in social media with food advertising.

Given the networked and fluid nature of social media, where – in contrast to broadcast media—advertising is presented to users not only from companies themselves but also via multiple other sources, including peers and celebrities who may be considered more trustworthy than brands, the study also examined effects of the source of advertising posts viewed.

The study investigated adolescents’ responses to advertisements for three types of products in social media: unhealthy food, healthier food, and non-food. It also measured effects of the source of these social media advertising posts. It is novel owing to its inclusion of healthy, unhealthy and non-food items, the social contexts of advertising received by adolescents in social media, and in combining objective measures of attention using eye-tracking technology not only with brand memory but also with self-report of social responses: we are unaware of any previous study to do this.

Assessing social responses, memory and attention, we hypothesized that participants will respond more positively to unhealthy food brands, compared to healthy food or non-food brands; and to advertising posts whose source appeared to be a celebrity or a fictional peer, rather than a brand or company.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This mixed methods study involved two experimental studies (with outcome measures in three domains) designed to replicate a social media viewing experience. Both studies involved repeated measures true experiments with a 3 × 3 factorial design using a sequence of profile news feeds designed to mimic Facebook. In these, the content of target advertising posts varied systematically between healthy food, unhealthy food, and non-food; the source varied systematically between peer, celebrity, and company. Each combination of factors appeared four times (i.e., four trials) with a different brand each time (total 36 feeds). Adolescents’ responses to advertisements in social media were measured through three modalities: social responses, memory for brands, and attention to advertising posts. Dependent variables were

Study 1a Social responses

- (i)

likelihood to ‘share’ advertising posts

- (ii)

attitude to peer

Study1b: Memory for brands

- (iii)

free brand recall

- (iv)

prompted brand recognition

Study 2: Attention to advertising

- (v)

mean fixation duration

- (vi)

mean fixation count

2.2. Stimulus Material

Facebook ‘News Feed’. Facebook was the most widely used social media platform amongst adolescents in Ireland in the most comprehensive study available at the time of designing the materials [

8]. Ecologically valid stimuli were created to resemble Facebook News Feeds of fictitious teen users (36 males and 36 females). To match Facebook’s design, each page contained a small profile picture and owner’s name (See

Figure 1). Profile usernames were generated using common first names of the cohort identified in the Irish Central Statistics Office release for 2000 [

60].

Each ‘profile view’ contained one advertising post (the target image), and two distractors. Each advertising post represented one content/source condition (e.g., unhealthy food ad, posted by a peer; or non-food ad, posted by a celebrity). For the two distractor posts, one was a full post with an image e.g., quotations, cartoons, status updates and images of people, animals and places. The other was text-only, shortened to give the impression that the feed continued below the screen.

In half the feeds, the advertising post appeared first. While the usernames and distractor images differed by gender, advertising images remained the same. To reduce potential confounds, the ‘like’, ‘share’ and ‘comment’ buttons contained no additional information, as ‘likes’ have been found to influence adolescents’ attitudes toward content.

2.3. Selection of Brands and Products for Advertising Posts

Food products were selected from local and international products widely available in local retail outlets and likely to be familiar to teenagers. World Health Organization 2015 Nutrient Profile Model guidelines for advertising to children [

61] were applied to identify foods considered suitable to market to children such as snacks, breakfast cereals and fruit, and unsuitable items such as crisps (potato chips), chocolate and fast food. Non-food items were selected from those of interest to many young adolescents, such as technology, games, sports and cosmetics.

2.4. Selection of Sources for Advertising Posts

‘Peer’-originating advertising posts were created as if originating from other fictitious profile owners; ‘celebrity’ posts from celebrities representing music, sporting and movies likely to be popular with that age group; and ‘company’ posts from the brand or product of interest.

Two sets of social media feed images were developed so that male and female participants viewed gender-matched profile views. Celebrity posts were gender-matched to participants as research demonstrates favourability for celebrities of the same sex in adolescents [

62,

63]; however, the food brands viewed were identical. For example, Taylor Swift, a female singer, has promoted Subway sandwiches; Christiano Ronaldo, a male soccer player, has promoted the same product. In the non-food category advertising posts were for gender-normative items (e.g., clothing for females and computer games for males).

Table 1 lists celebrities featured in the study and

Table 2 lists all products shown in the advertising posts created for the study.

Finally, two young people aged 18 years (both female, accessed through personal contacts) reviewed all the profile views to consider authenticity for teens. Following their suggestions, some images were changed for more youth-oriented pictures; more hashtags, emojis, and exclamation marks were included in the text.

2.5. Ethics and Participant Recruitment

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of University College Dublin (Attitude: TGREC-PSY 2015-27; Memory: TGREC-PSY 2015-33; Eye-tracking: TGREC-PSY 2016-7).

All participants and their parents gave informed written consent before participation. The study information stated its aim to explore social media and advertising but did not indicate a focus on food advertising. Participants were debriefed after taking part.

Participants were recruited through secondary schools in Ireland (fee-paying and non-feeing paying, single-sex and co-educational schools), youth clubs and Facebook advertising. The youngest participants recruited were 13 years, the age at which social networks’ terms and conditions permit their use. Power analysis (G*Power) [

64] demonstrated that to be sufficiently powered (1 −

β = 0.8) to detect small effect sizes (f = 0.15), the current design required a total sample size of 39. Participants for Study 1 (

n = 72) were aged 13–14 years; participants for Study 2 (

n = 81) were aged 13–17 years.

5. Discussion

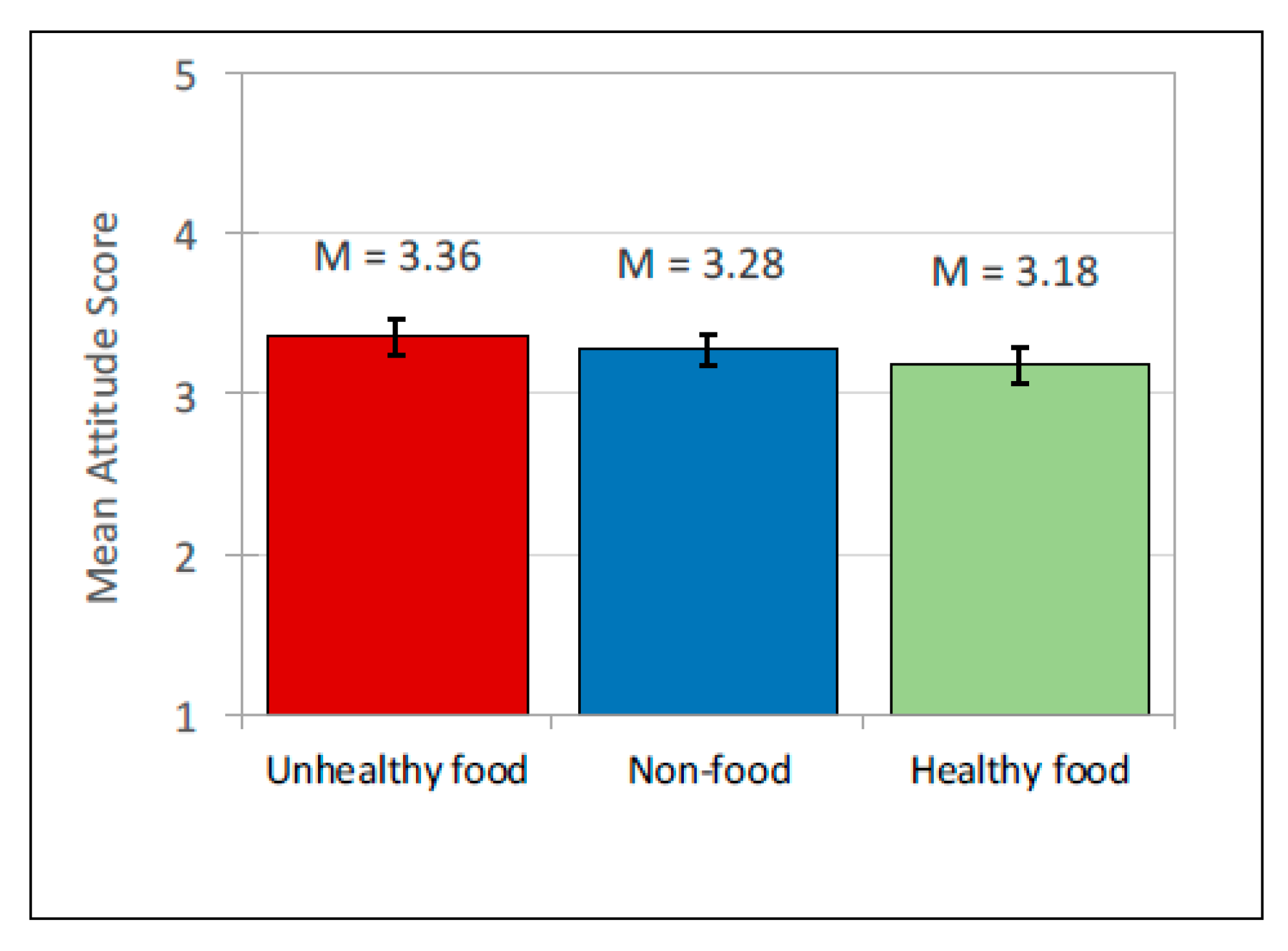

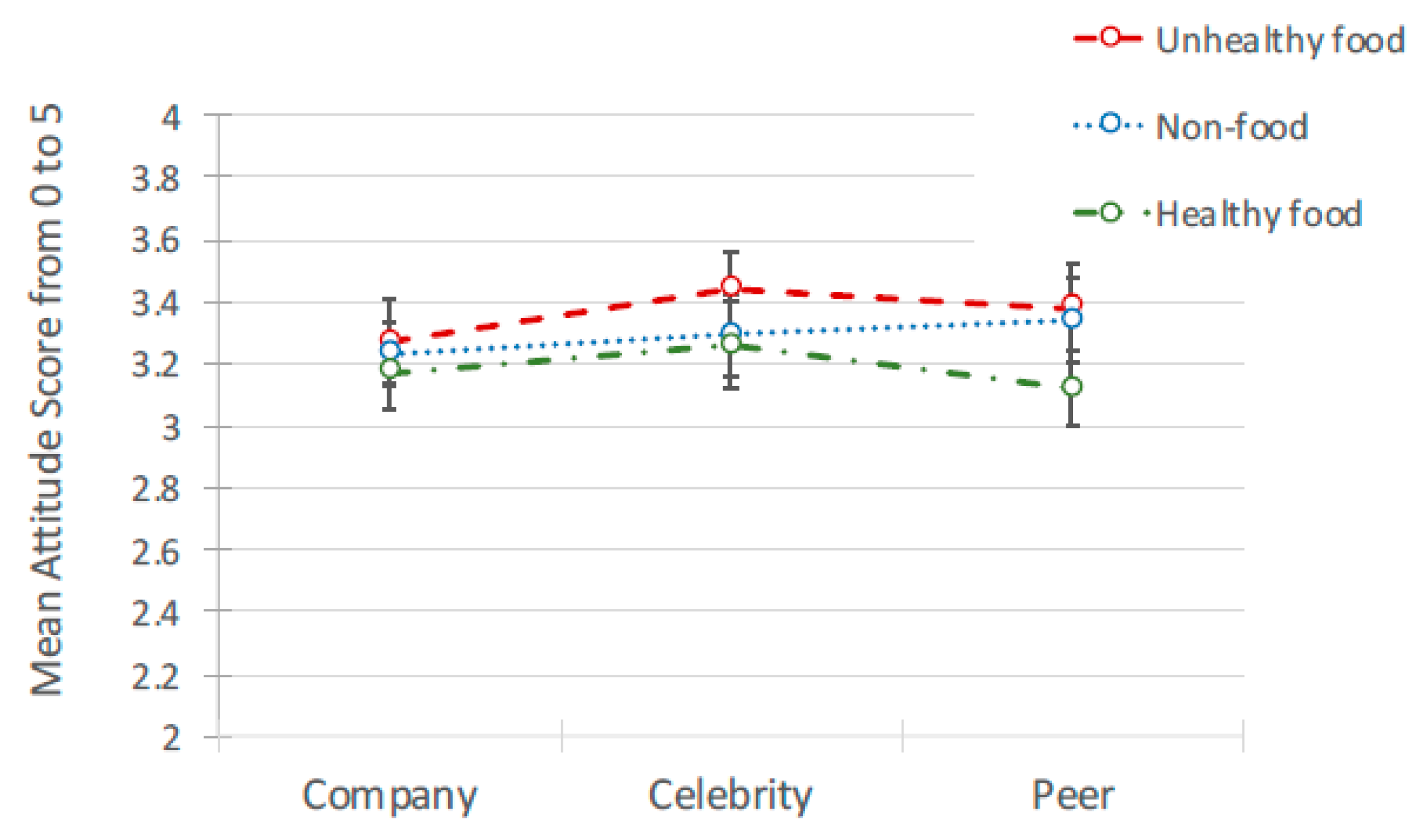

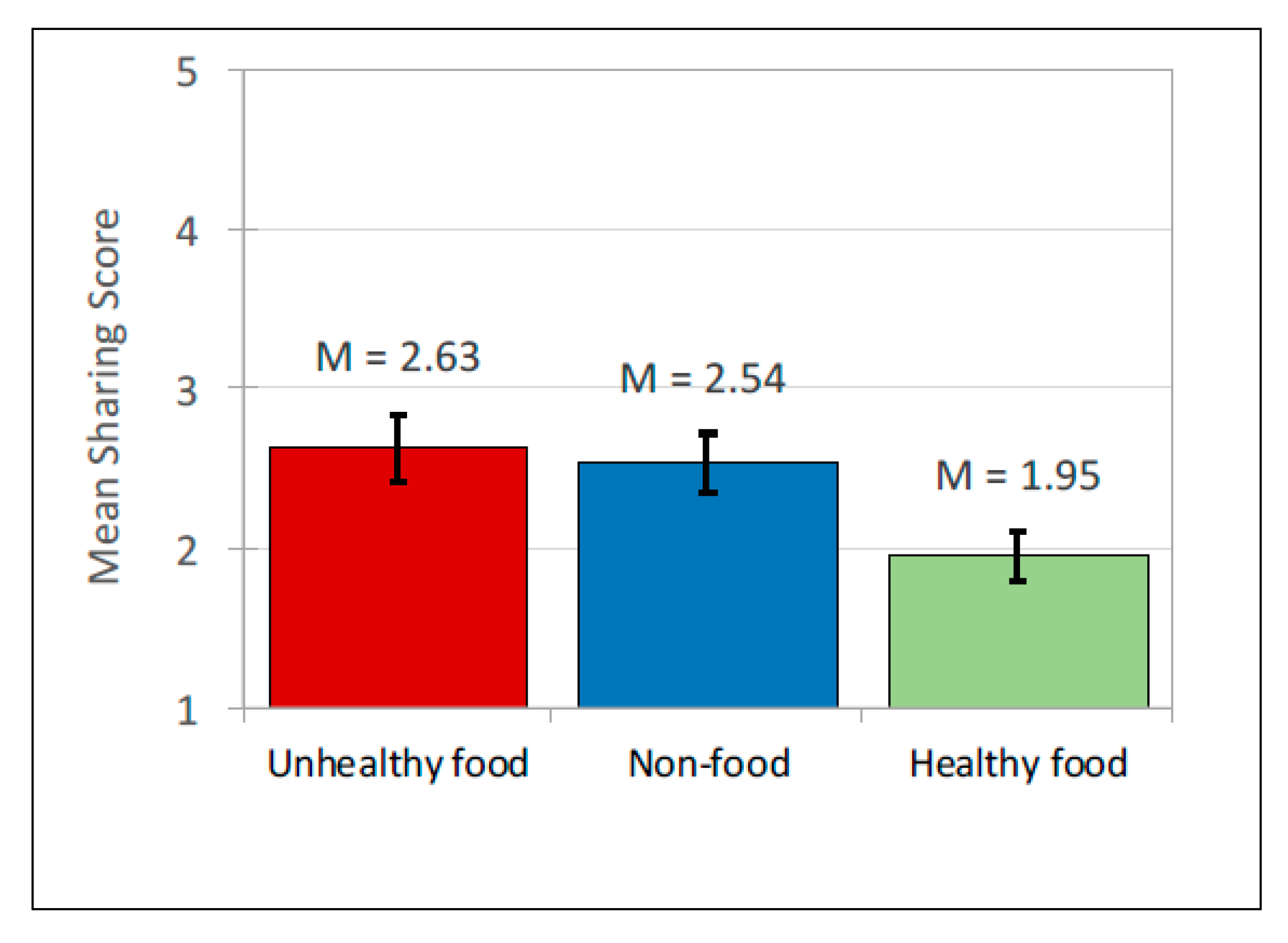

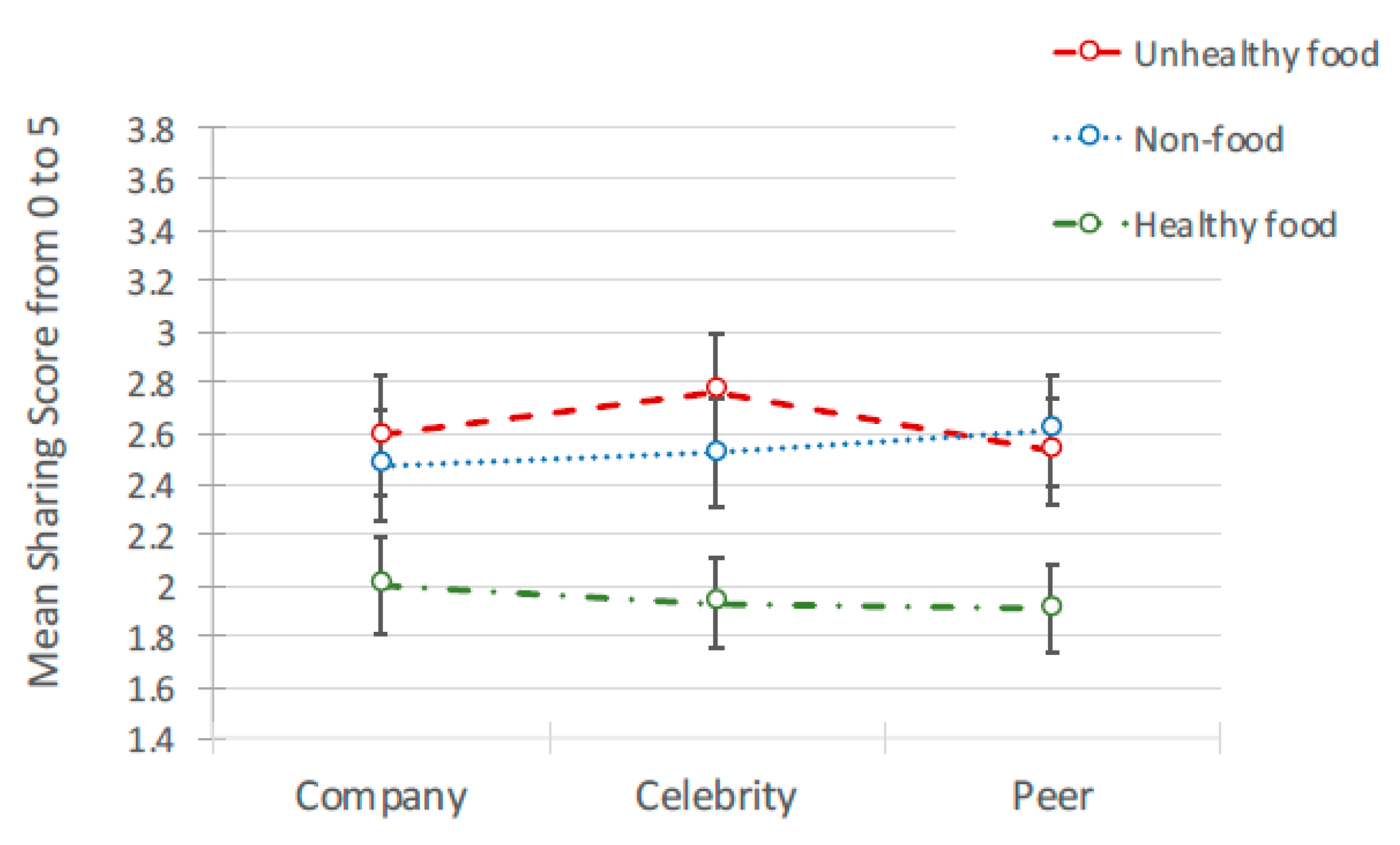

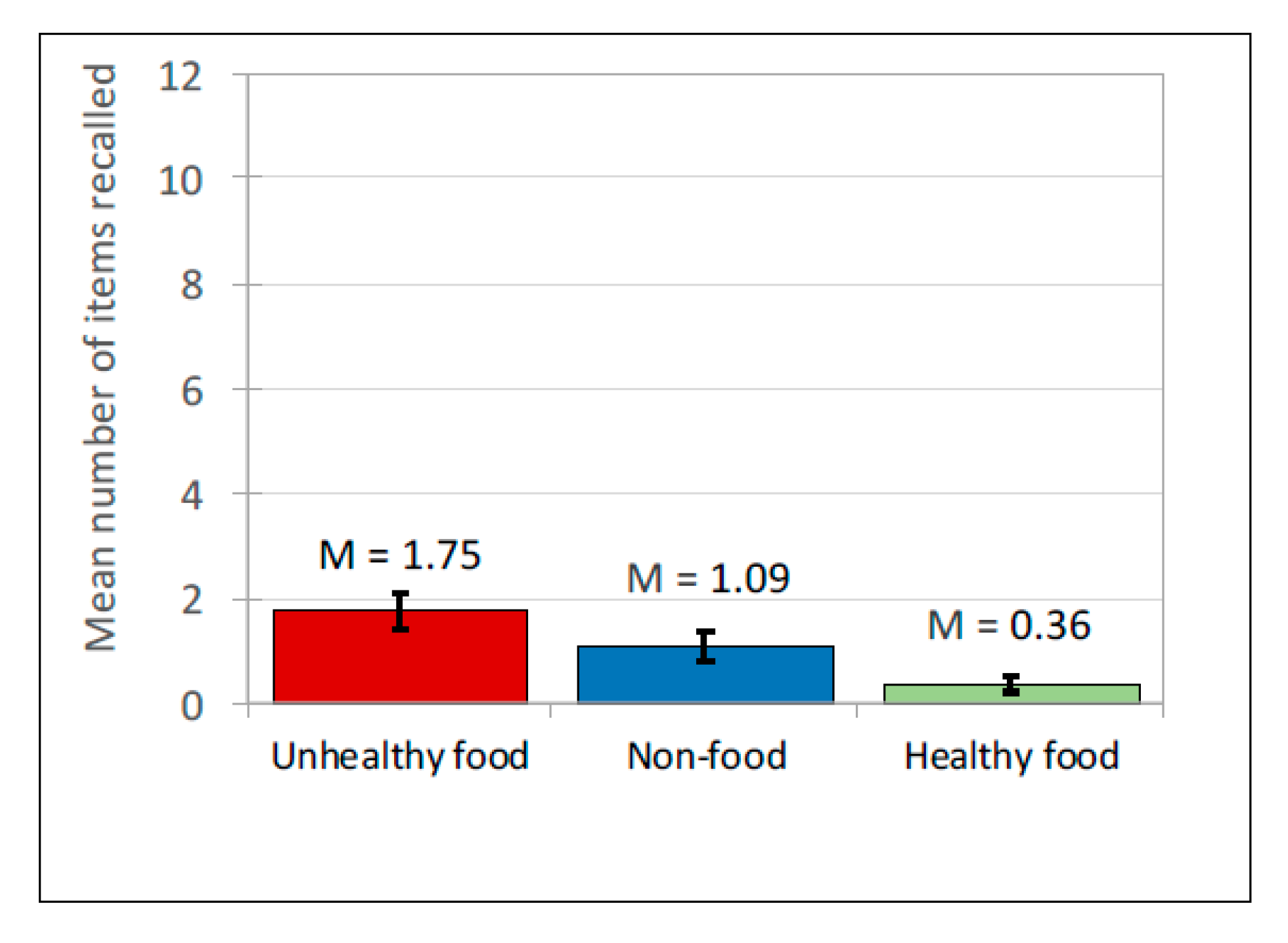

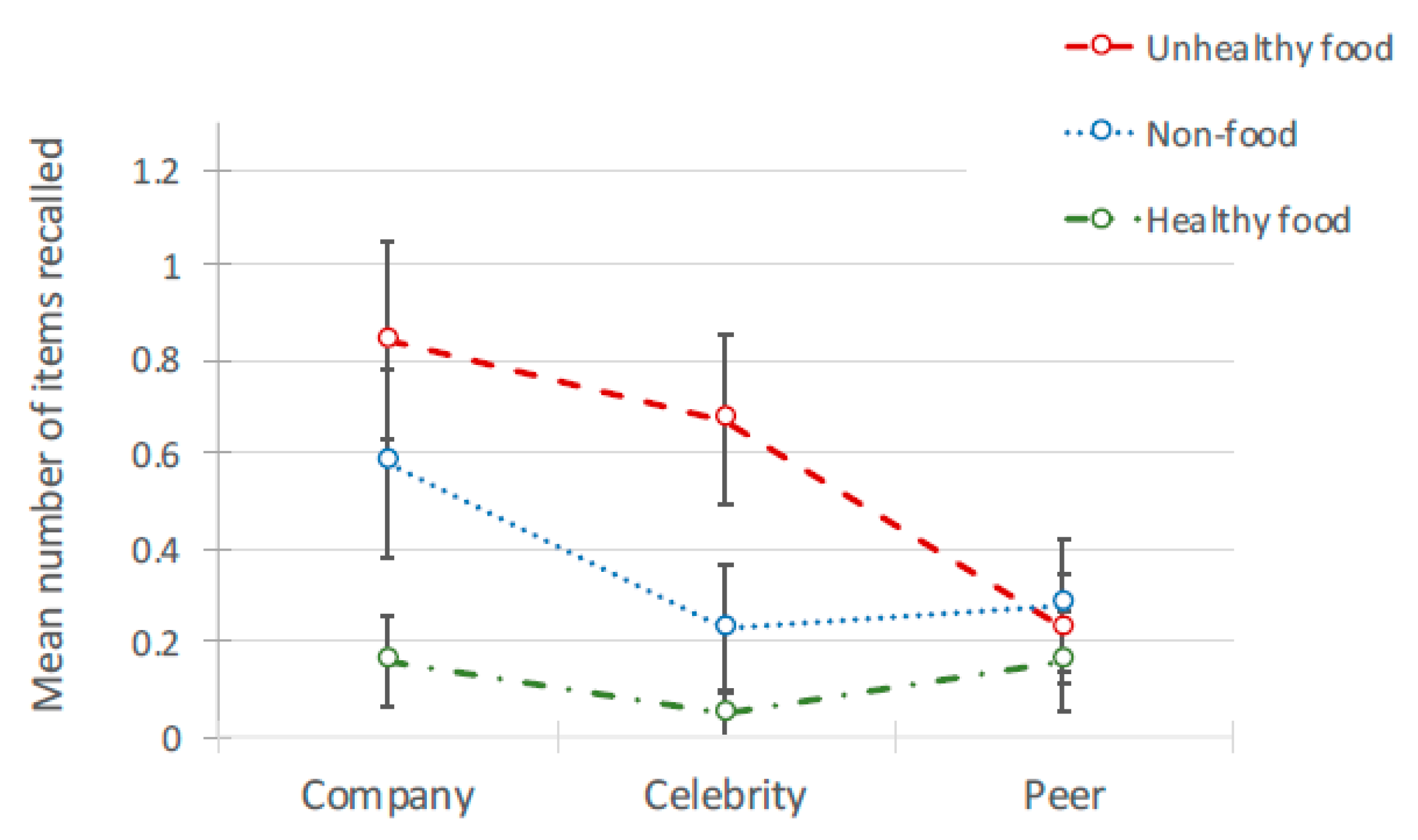

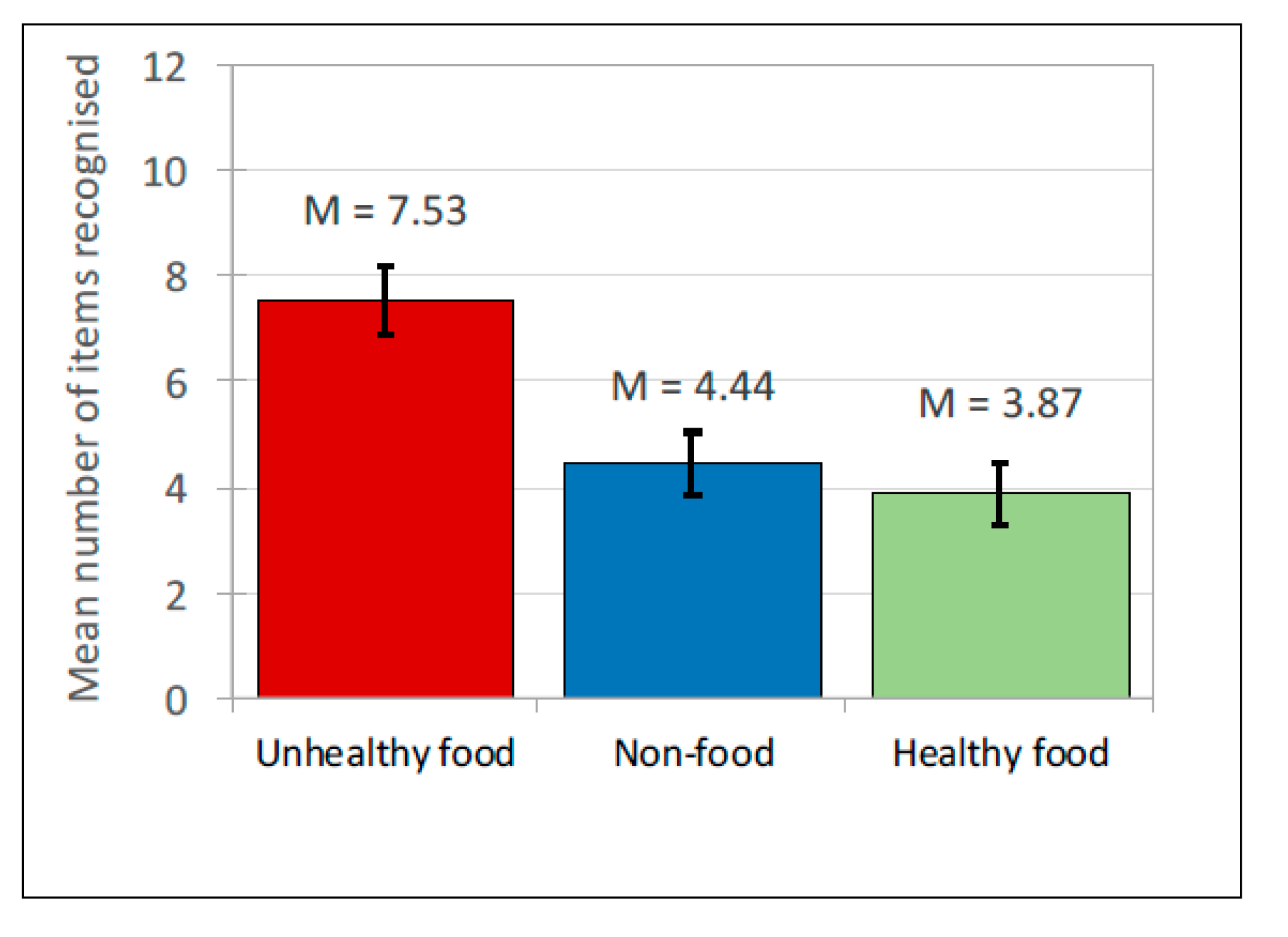

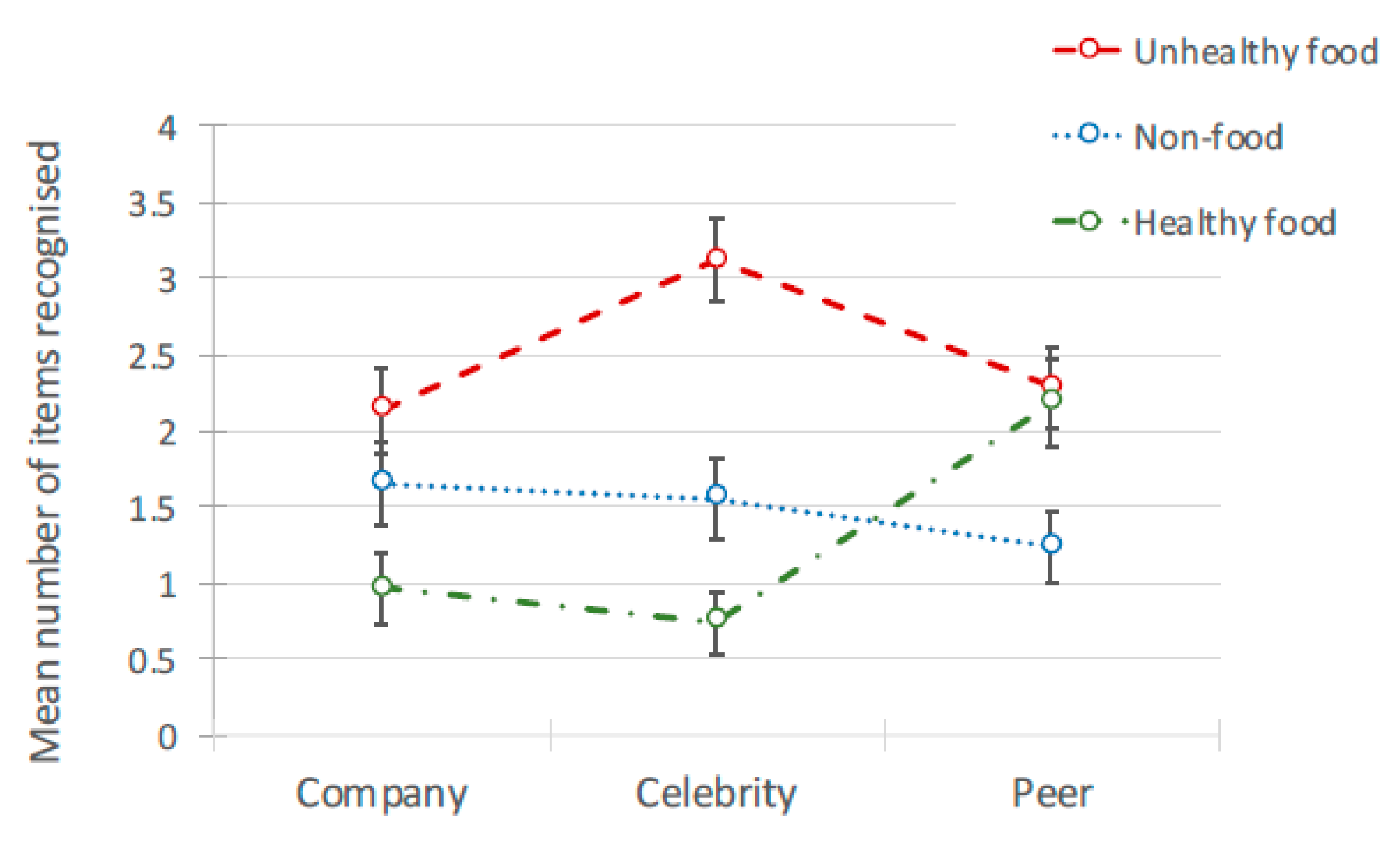

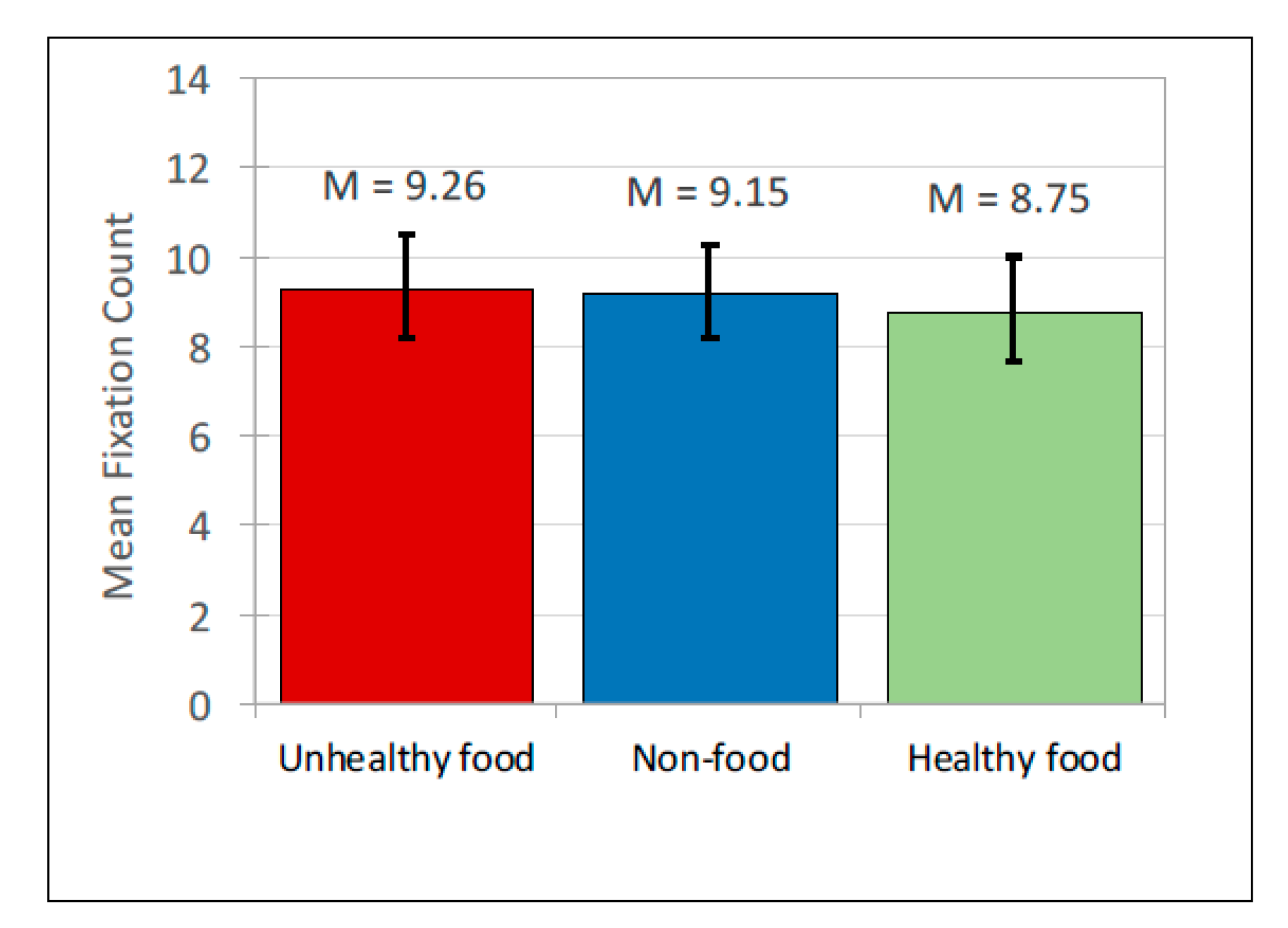

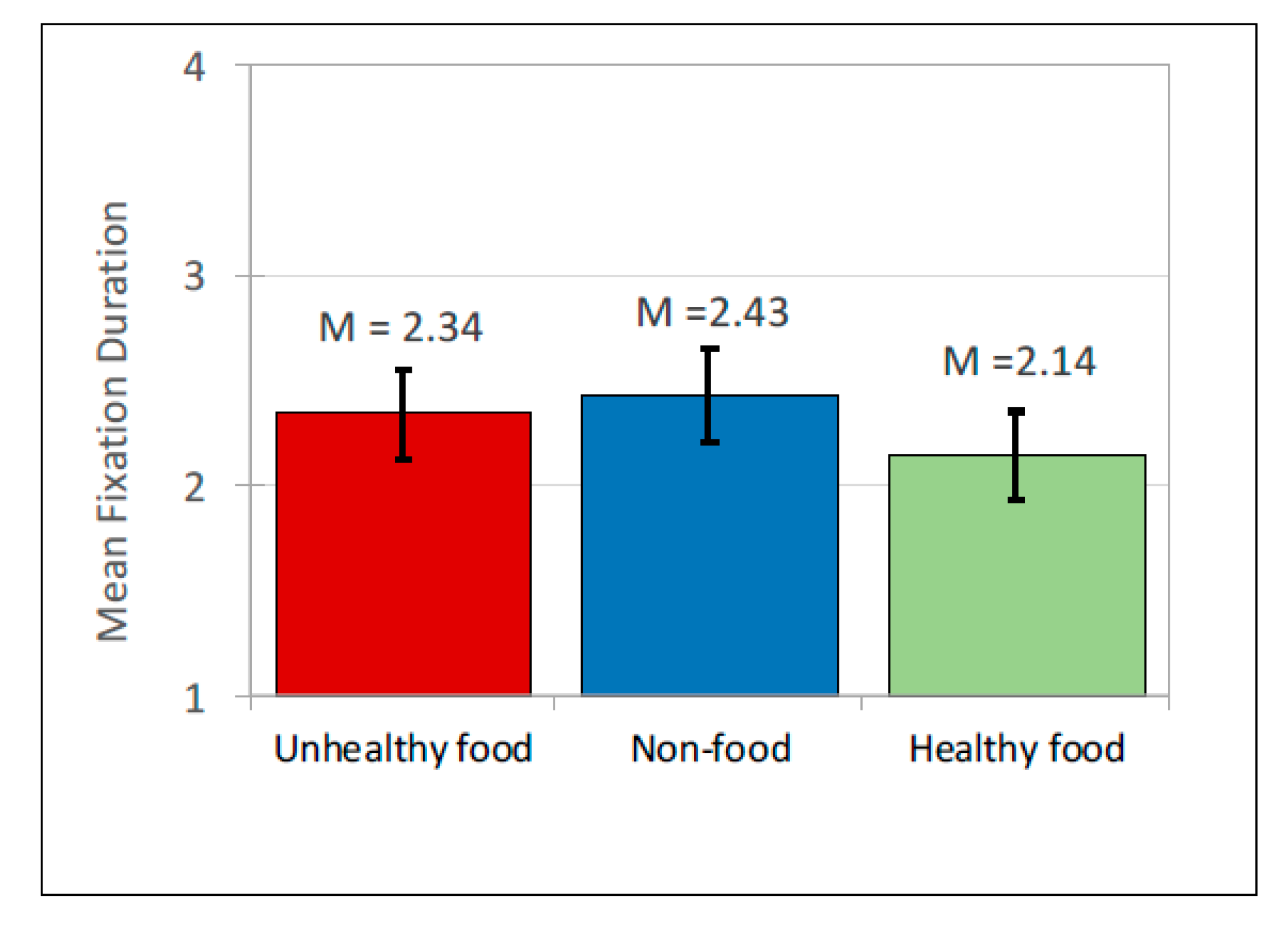

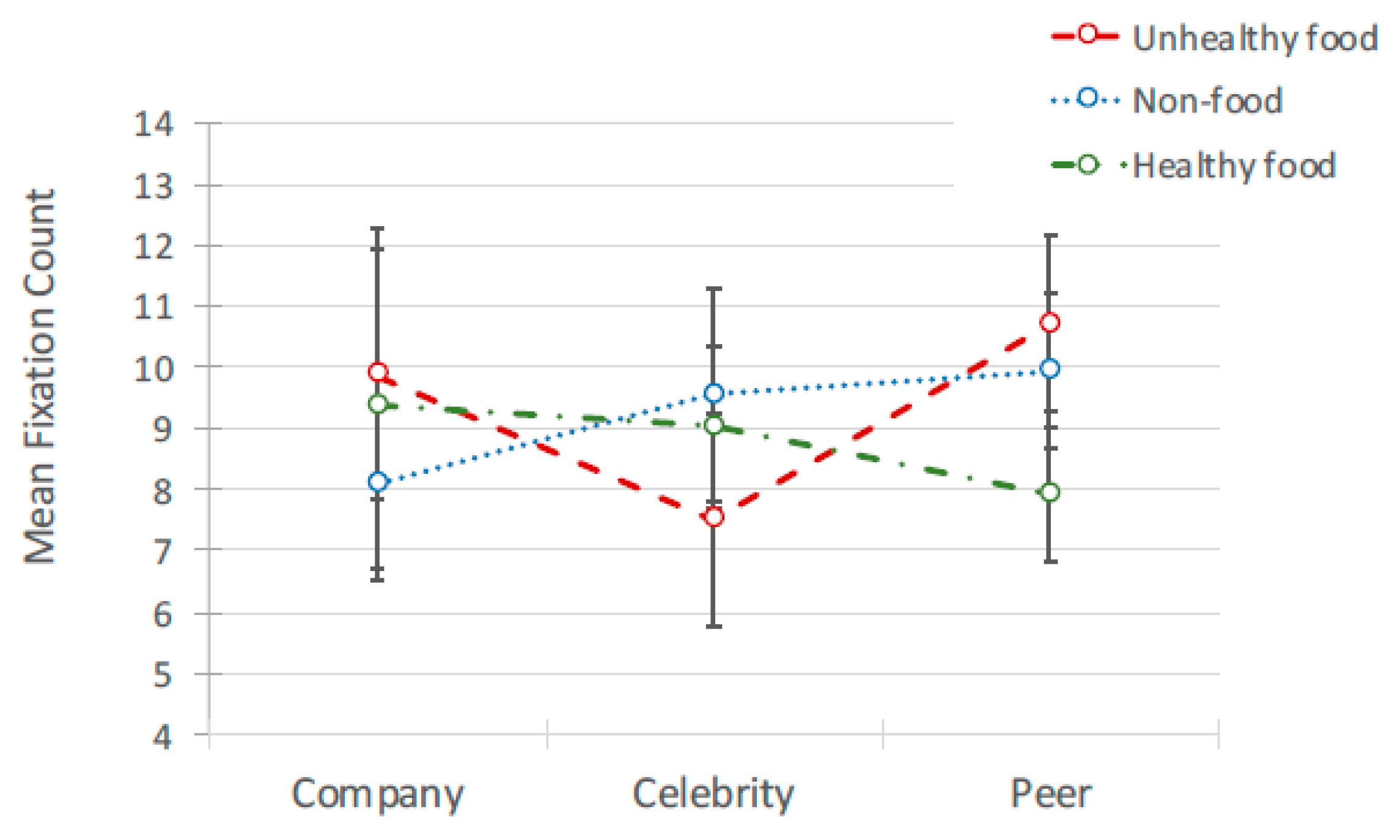

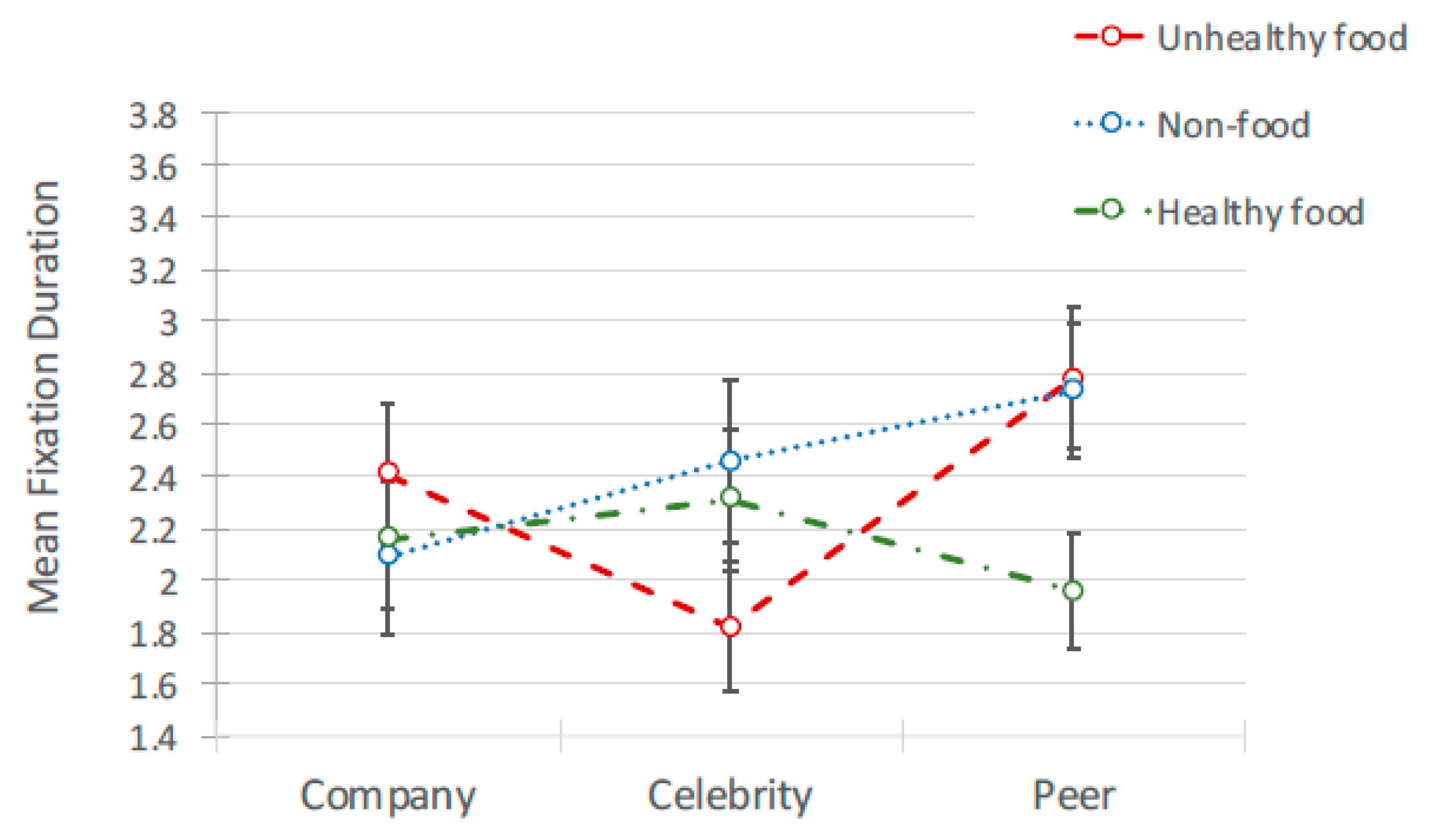

This is the first study, as far as we are aware, to examine adolescent responses in social, memory, and attention domains to the same set of social media advertising for a range of products and sources. We found a consistent pattern. When young people stated which posts they would share in social media; when assessing their attitude to peers, (Study 1a); when attempting to recall brands they had seen; or recognise them from a list (Study 1b), the young people in this study responded significantly more positively to unhealthy food advertising compared to non-food advertising, and to both these product types significantly more positively than to healthy food advertising. Although free recall rates overall were low, recall for unhealthy food brands was nearly five times as great as for healthy food brands and nearly twice as great as for non-food brands. Furthermore, when prompted from a list that included distractors, young people recognised many unhealthy food brands and did so at approximately twice the rate of healthy food and non-food brands. Finally, for measures of attention (Study 2), adolescents did not differ in the types of ads they looked at (fixation count), but they looked at ads for unhealthy foods for significantly longer (fixation duration).

In addition to the multiple domains measured in this study, a further novel feature was that it examined interactions between the content of a social media advertising post and its source. Here the findings were less straightforward. The source of the advertising post did not affect young people’s likelihood to share it, nor did the source affect their attitudes to the fictional peer whose social media account they were viewing (Study 1a). This suggests that, for social responses to advertising content in social media, adolescents are as susceptible to effects when ads originate from a company or brand, as they are when ads are shared by celebrities or their peer group. However, when measuring memory for brands (Study 1b), and fixation duration (Study 2), source did interact with ad content, although the patterns here were contradictory for these two domains. The fixation duration findings suggest that young people attended to unhealthy food posts from their peers for longer than from other sources, and to healthy food advertising posts from celebrities for longer than from other sources. Yet when participants’ free recall for brands was measured, the findings were different. For ads shared by celebrities and companies, participants recalled significantly more unhealthy food brands than non-food or healthy food brands, yet for ads shared by peers, recall did not differ significantly. Similarly, for recognition, when ads were shared by celebrities and companies, participants recognised unhealthy food brands significantly more, followed by non-food, with healthy food recognised least; yet when ads were shared by peers, recognition of unhealthy and healthy food brands did not differ, and non-food brands were recognised significantly less than food brands.

Taken together, therefore, the study findings indicate that adolescents attended to all of the advertising they saw in social media, but they viewed unhealthy food advertising posts for longer. They also recalled unhealthy food brands more, recognised them more, were more likely to share them, and had more positive views of peers in whose social media accounts they saw unhealthy food advertising posts.

The findings regarding source of the post were complex and contradictory and the interactions between product type and the source of the advertising post warrant further investigation. As unhealthy food brands are frequently promoted by celebrities popular with adolescents [

45,

46], it is notable that we found that celebrity-shared posts for unhealthy brands were recalled significantly more frequently than posts from other sources. Interestingly, brand recall and recognition for unhealthy and healthy foods did not vary for peer-shared posts. This suggests the possibility that young adolescents may be most open to healthy food communications from their own peers, and therefore that if seeking to promote healthier practices in social media, peer-led social marketing [

65] might be more likely to succeed than celebrity-led or public service messages.

Advertising recall and recognition is significant for children’s health as it is the first step in the hierarchy of food advertising effects that is hypothesised to lead to changes in eating behaviour and body weight gain [

49]. Meta-analysis of 45 studies has concluded that viewing food images provokes as strong a desire to eat as exposure to food itself [

66], and further analyses indicate that attentional bias towards food images is greater in those who eat more [

57,

67,

68,

69]. Furthermore, neural responses to fast food advertising predict intake [

70].

The findings for attention were least straightforward of the three outcome domains in this study and this mirrors previous findings in this field [

69,

71].As eye-tracking measures eye movement behaviour as an indirect index of processing, it is difficult to separate out the relative contributions of expectation, pre-existing attitudes, and bottom-up perceptual features of the stimulus. Given the conditions included multiple trials with varied products and stimuli, we might infer that the present findings are driven by expectations about types of products and who posts them rather pre-existing knowledge of a product or perceptual features of a specific ad. At the same time, it could be argued that as food is an item children engage with daily from infancy, and as almost all existing advertising is for unhealthy foods, it is likely that in this domain, young people have already developed perceptual fluency for unhealthy food marketing which in turn increases liking [

72] when presented with stimuli. Thus, even brief attention to unhealthy food advertisements may reinforce positive attitudes, and furthermore, less attention is required for recall for unhealthy, compared to healthy and non-food advertising [

73]. The exact role and relationships of visual attention, perceptual fluency, existing implicit attitudes and subsequent behaviours remain to be clarified and offer rich potential for future research.

The findings for peer attitudes echo studies of young people’s views of unhealthy food in other contexts. For example, Swedish 14-year-olds, when creating their own images on Instagram, included significantly more images of unhealthy food on their online profiles than healthier options [

40]; 13 to 15-year-olds at school in the UK believed healthy eating was ‘uncool’ and damaged the self-image they wanted to convey to peers [

74]. As school friends’ Body Mass Indices (BMI) in Australian and American adolescents were related, with those of higher BMIs being most similar [

75], participants’ greatest likelihood to share posts for unhealthy food is a concern as it indicates that unhealthy food marketing is the type young people are most likely to spread among networks.

Age was also pertinent to adolescents’ attention as older participants looked more and for longer at the advertising posts. The development of control systems as adolescents age allows them to retain attention for longer than younger adolescents [

76]. They also spend more time viewing social media later in adolescence [

7]. Although it is often posited that cognitive capacity to recognise advertising and its persuasive intent is fully developed by adolescence (see discussion in WHO, 2016 [

6]), the findings of the present study indicate that attention paid to advertising posts increases with age, suggesting potential greater vulnerability.

Participants’ positive attitudes to peers with unhealthy food advertising content in social media, and their greater willingness to ‘share’ it, indicates that this form of advertising likely contributes to adolescent identity expression online [

77]. Social identity theories describe how people come to develop a sense of self, or ‘who I am’, based on features of the social groups to which they belong; group identities are essential parts of the self-concept that “form a socially constructed sense of who and what ‘we’ are and also who and what ‘we’ are not” [

78]. One of the ways in which adolescents establish an identity as distinct from older generations is through eating and identifying with widely marketed ‘junk’ foods, a form of adolescent identity expression that reflects marketing campaigns and that has been found in multiple cultures over decades [

77]. As social media are sites in which adolescents engage in the central developmental task of identity formation [

79], unhealthy food marketing is likely to become enmeshed in this process.

Adolescents’ attention to unhealthy food advertising, their recall of this advertising and their evaluation of peers and likelihood to share this content through their networks, all constitute important facets of their responses to advertising content in a media-saturated environment. These early findings for social media effects on young adolescents’ recall and recognition of food and other brands have implications for future research and policy action to protect and promote health. Before considering these, we address strengths and limitations of the study.

5.1. Limitations

Researchers examining digital media practices and effects face substantial design challenges. In contrast to broadcast media, users’ experiences in social media (including the advertising they see) are personalized, yet accessing young people’s actual social media accounts for research is particularly ethically challenging [

6,

80]. This study therefore featured fictional peers, and celebrities that are popular with participants’ age group. How this impacts on the ecological validity of the study is uncertain, although it seems reasonable to infer that effects might be greater for actual friends and celebrities they personally follow.

Furthermore, young people’s digital platforms preferences can change rapidly. Facebook was the most-used social media platform among Irish teens when the study was designed [

8]; by the time it was carried out, Snapchat and Instagram had become increasingly popular [

81], and at the time of writing, Snapchat had become less of a focus with the rise of TikTok [

82]. Still, Facebook continues to be a widely used platform [

7]. We are unaware of any studies comparing advertising effects across platforms. However, as the effects found in this study mirror those identified in television, it suggests that they are likely to transfer to other digital platforms as well.

5.2. Strengths

The study is the first we know of that examines young adolescents’ social responses, memory and attention of social media advertising posts for healthy, unhealthy and non-food brands in multiple social contexts. It benefits from integrating theory of social norms of food and social media with food marketing effects. The stimuli were designed with the input of young people, to closely simulate social media accounts. This feature, together with the fact that participants were blind to the aim of the study when viewing the feeds, was a major strength in the experiment, achieving a combination of ecological validity and levels of experimental control that are typically subjected to trade-off in research studies.

5.3. Implications for Research and Policy

This study adds to a nascent body of evidence indicating that food marketing in digital media is likely to contribute to adverse effects on adolescents’ health [

83]. Of interest for research in advertising effects is the contrast between the free and prompted recall rates found. Reflecting findings for much younger children [

84], this indicates that even when memory is more developed in adolescence, free recall remains a poor measure of advertising exposure compared to prompted recognition. Future areas of exploration are links between social responses to food marketing (sharing and peer assessment) and consumption patterns.

For policy, the findings indicate the likely vulnerability of young adolescents to food marketing. Engagement with food and beverage brands in social media is widespread: in the US, millions of adolescents follow these accounts [

15] and 70% of 1564 adolescents surveyed reported engaging with at least one brand and 35% with five or more [

85]. They will therefore receive food and beverage marketing, and the present study shows they are likely to share this with their networks. Furthermore, the impact of shared advertising for unhealthy products can be predicted to be disproportionately powerful, as adolescent social norms of eating and perception of others’ consumption skews towards unhealthy foods, and this in turn disproportionately affects adolescents’ eating [

38].

Adolescents are under-represented in research regarding food marketing and are typically neglected by regulatory measures aimed at protecting children from the negative health effects of unhealthy food marketing [

6]. This study indicates that the present global focus on protecting children up to 12 years old may leave a substantial proportion of young people, at the age when their social media use rises rapidly [

7], unprotected from digital food marketing [

86] and thus in a position where their rights to health, privacy and freedom from exploitation are infringed [

87].