PGC-1α-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches to Enhance Muscle Recovery in Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

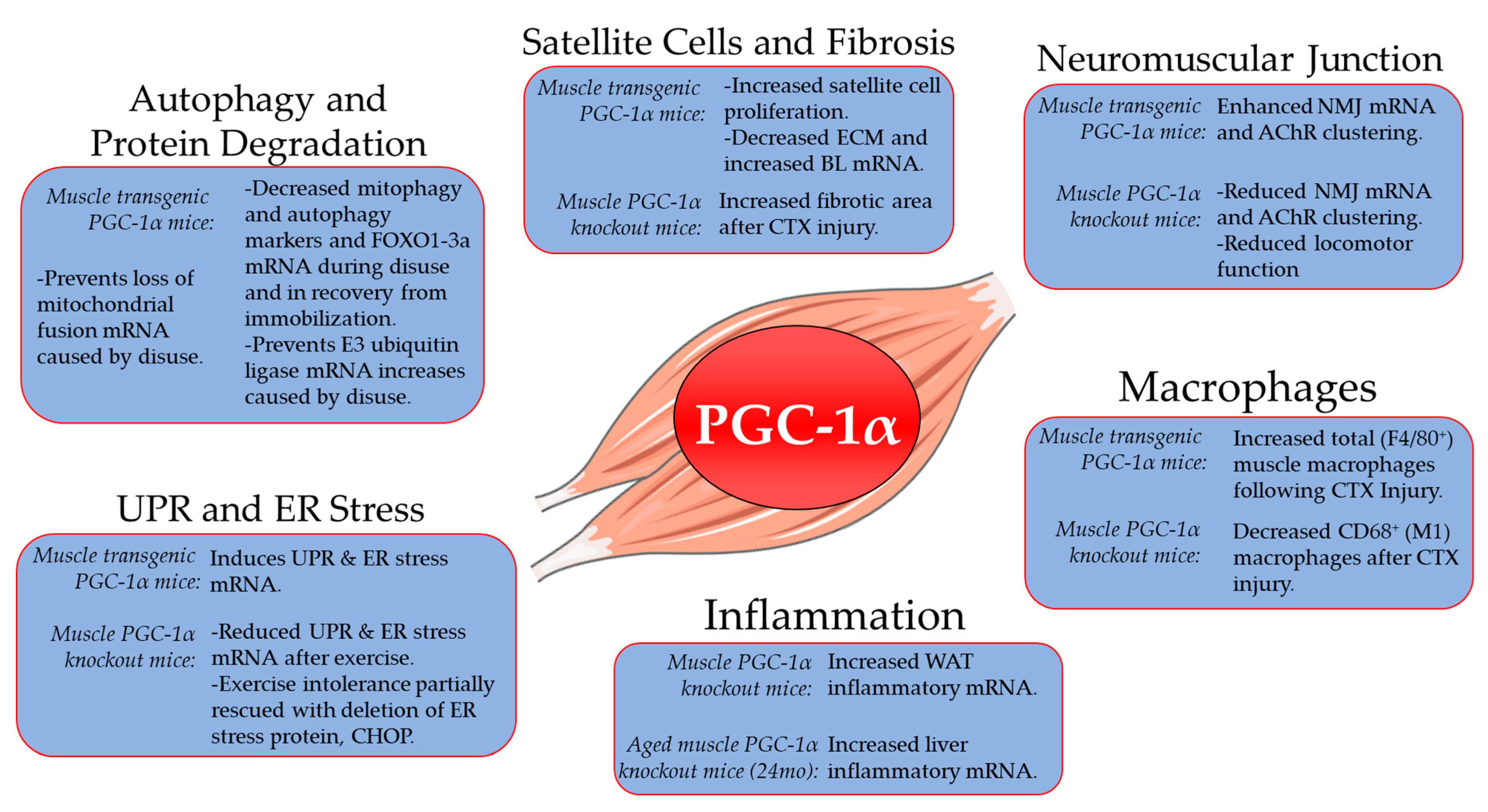

2. Role of PGC-1α in Skeletal Muscle Aging, Atrophy and Recovery from Disuse

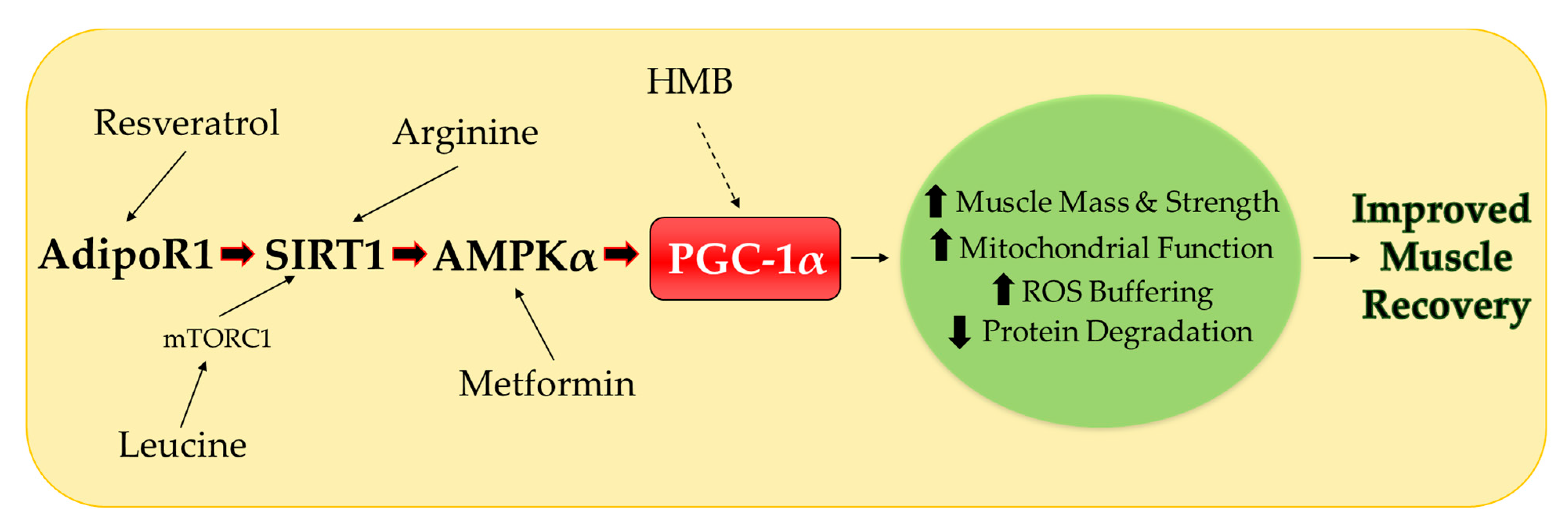

3. Potential Nutritional Therapies

3.1. Leucine

3.2. β-hydroxy-β-methylbuyrate (HMB)

3.3. Arginine

3.4. Resveratrol

4. Nutritional Therapies Combined with Metformin

4.1. Metformin

4.2. Metformin Combination Therapies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kehler, D.S.; Theou, O.; Rockwood, K. Bed rest and accelerated aging in relation to the musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems and frailty biomarkers: A review. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 124, 110643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkin, O.; McGuigan, P.; Thompson, D.; Stokes, K.A. A reduced activity model: A relevant tool for the study of ageing muscle. Biogerontology 2015, 17, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvid, L.G.; Suetta, C.; Nielsen, J.; Jensen, M.; Frandsen, U.; Ørtenblad, N.; Kjaer, M.; Aagaard, P. Aging impairs the recovery in mechanical muscle function following 4days of disuse. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, P.; Suetta, C.; Caserotti, P.; Magnusson, S.P.; Kjaer, M. Role of the nervous system in sarcopenia and muscle atrophy with aging: Strength training as a countermeasure. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetta, C.; Hvid, L.G.; Justesen, L.; Christensen, U.; Neergaard, K.; Simonsen, L.; Ørtenblad, N.; Magnusson, S.P.; Kjaer, M.; Aagaard, P. Effects of aging on human skeletal muscle after immobilization and retraining. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 107, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetta, C.A.; Frandsen, U.; Mackey, A.L.; Jensen, L.; Hvid, L.G.; Bayer, M.L.; Petersson, S.J.; Schrøder, H.D.; Andersen, J.L.; Aagaard, P.; et al. Ageing is associated with diminished muscle re-growth and myogenic precursor cell expansion early after immobility-induced atrophy in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 3789–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvid, L.G.; Aagaard, P.; Justesen, L.; Bayer, M.L.; Andersen, J.L.; Ørtenblad, N.; Kjaer, M.; Suetta, C. Effects of aging on muscle mechanical function and muscle fiber morphology during short-term immobilization and subsequent retraining. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pišot, R.; Marusic, U.; Biolo, G.; Mazzucco, S.; Lazzer, S.; Grassi, B.; Reggiani, C.; Toniolo, L.; Di Prampero, P.E.; Passaro, A.; et al. Greater loss in muscle mass and function but smaller metabolic alterations in older compared with younger men following 2 wk of bed rest and recovery. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 120, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.R.; Confides, A.L.; Moore-Reed, S.; Hoch, J.M.; Dupont-Versteegden, E.E. Regrowth after skeletal muscle atrophy is impaired in aged rats, despite similar responses in signaling pathways. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 64, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baehr, L.M.; West, D.W.; Marcotte, G.; Marshall, A.G.; De Sousa, L.G.; Baar, K.; Bodine, S.C. Age-related deficits in skeletal muscle recovery following disuse are associated with neuromuscular junction instability and ER stress, not impaired protein synthesis. Aging 2016, 8, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaud, D.; Jacot, E.; A DeFronzo, R.; Maeder, E.; Jequier, E.; Felber, J.-P. The Effect of Graded Doses of Insulin on Total Glucose Uptake, Glucose Oxidation, and Glucose Storage in Man. Diabetes 1982, 31, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Garg, A.; Xu, D.; Bruner, M.; Fazel-Rezai, R.; Blaber, A.P.; Tavakolian, K. Skeletal Muscle Pump Drives Control of Cardiovascular and Postural Systems. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-J.; Latham, N.K. Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, CD002759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, T.P.; Bolster, D.R. Insights into muscle atrophy and recovery pathway based on genetic models. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2006, 9, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, H.C.; Strycker, L.A.; Senesac, H.A.; Hocker, A.D.; Smolkowski, K.; Shah, S.N.; Jewett, B.A. Essential amino acid supplementation in patients following total knee arthroplasty. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 4654–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Peel, C.; Bamman, M.M.; Allman, R.M. Exercise program implementation proves not feasible during acute care hospitalization. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2007, 43, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.L.; Yeo, D. Mitochondrial dysregulation and muscle disuse atrophy. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handschin, C.; Kobayashi, Y.M.; Chin, S.; Seale, P.; Campbell, K.P.; Spiegelman, B.M. PGC-1 regulates the neuromuscular junction program and ameliorates Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ruas, J.L.; Estall, J.L.; Rasbach, K.A.; Choi, J.H.; Ye, L.; Bostroem, P.; Tyra, H.M.; Crawford, R.W.; Campbell, K.P.; et al. The Unfolded Protein Response Mediates Adaptation to Exercise in Skeletal Muscle through a PGC-1α/ATF6α Complex. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinulovic, I.; Furrer, R.; Di Fulvio, S.; Ferry, A.; Beer, M.; Handschin, C. PGC-1α modulates necrosis, inflammatory response, and fibrotic tissue formation in injured skeletal muscle. Skelet. Muscle 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenz, T. Mitochondria and PGC-1α in Aging and Age-Associated Diseases. J. Aging Res. 2011, 2011, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäger, S.; Handschin, C.; St-Pierre, J.; Spiegelman, B.M. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12017–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amat, R.; Planavila, A.; Chen, S.L.; Iglesias, R.; Giralt, M.; Villarroya, F. SIRT1 Controls the Transcription of the Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor-γ Co-activator-1α (PGC-1α) Gene in Skeletal Muscle through the PGC-1α Autoregulatory Loop and Interaction with MyoD. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 21872–21880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, M.; Lin, J.; Handschin, C.; Yang, W.; Arany, Z.P.; Lecker, S.H.; Goldberg, A.L.; Spiegelman, B.M. PGC-1 protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 action and atrophy-specific gene transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 16260–16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.; Ji, L.L. PGC-1α overexpression via local transfection attenuates mitophagy pathway in muscle disuse atrophy. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 93, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavino, J.; Brocca, L.; Sandri, M.; Bottinelli, R.; Pellegrino, M.A. PGC1-α over-expression prevents metabolic alterations and soleus muscle atrophy in hindlimb unloaded mice. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 4575–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavino, J.; Brocca, L.; Sandri, M.; Grassi, B.; Bottinelli, R.; Pellegrino, M.A. The role of alterations in mitochondrial dynamics and PGC-1α over-expression in fast muscle atrophy following hindlimb unloading. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 1981–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.F.; Santos, G.; Schnyder, S.; Handschin, C. PGC-1α affects aging-related changes in muscle and motor function by modulating specific exercise-mediated changes in old mice. Aging Cell 2017, 17, e12697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinulovic, I.; Furrer, R.; Beer, M.; Ferry, A.; Cardel, B.; Handschin, C. Muscle PGC-1α modulates satellite cell number and proliferation by remodeling the stem cell niche. Skelet. Muscle 2016, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sczelecki, S.; Besse-Patin, A.; Abboud, A.; Kleiner, S.; Laznik-Bogoslavski, D.; Wrann, C.D.; Ruas, J.L.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Estall, J.L. Loss of Pgc-1α expression in aging mouse muscle potentiates glucose intolerance and systemic inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2014, 306, E157–E167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arentson-Lantz, E.J.; English, K.L.; Paddon-Jones, D.; Fry, C.S. Fourteen days of bed rest induces a decline in satellite cell content and robust atrophy of skeletal muscle fibers in middle-aged adults. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 120, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brack, A.S.; Conboy, M.J.; Roy, S.; Lee, M.; Kuo, C.J.; Keller, C.; Rando, T.A. Increased Wnt Signaling During Aging Alters Muscle Stem Cell Fate and Increases Fibrosis. Science 2007, 317, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baehr, L.M.; West, D.W.D.; Marshall, A.G.; Marcotte, G.R.; Baar, K.; Bodine, S.C. Muscle-specific and age-related changes in protein synthesis and protein degradation in response to hindlimb unloading in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122, 1336–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demangel, R.; Treffel, L.; Py, G.; Brioche, T.; Pagano, A.F.; Bareille, M.-P.; Beck, A.; Pessemesse, L.; Candau, R.; Gharib, C.; et al. Early structural and functional signature of 3-day human skeletal muscle disuse using the dry immersion model. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 4301–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, A.R.; Suer, M.K.; Wolff, C.A.; Harber, M.P. Markers of Human Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Quality Control: Effects of Age and Aerobic Exercise Training. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 69, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Poulsen, P.; Carlsson, E.; Ridderstråle, M.; Almgren, P.; Wojtaszewski, J.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Groop, L.; Vaag, A. Multiple environmental and genetic factors influence skeletal muscle PGC-1α and PGC-1β gene expression in twins. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabi, B.; Ljubicic, V.; Menzies, K.J.; Huang, J.H.; Saleem, A.; Hood, D.A. Mitochondrial function and apoptotic susceptibility in aging skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 2008, 7, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Lertwattanarak, R.; Lefort, N.; Molina-Carrion, M.; Joya-Galeana, J.; Bowen, B.P.; Garduno-Garcia, J.D.J.; Abdul-Ghani, M.; Richardson, A.; DeFronzo, R.A.; et al. Reduction in Reactive Oxygen Species Production by Mitochondria From Elderly Subjects With Normal and Impaired Glucose Tolerance. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2051–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Chung, E.; Diffee, G.; Ji, L.L. Exercise training attenuates aging-associated mitochondrial dysfunction in rat skeletal muscle: Role of PGC-1α. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, S.M.; Dyle, M.C.; Kunkel, S.D.; Bullard, S.A.; Bongers, K.S.; Fox, D.K.; Dierdorff, J.M.; Foster, E.D.; Adams, C.M. Stress-induced Skeletal Muscle Gadd45a Expression Reprograms Myonuclei and Causes Muscle Atrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 27290–27301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gonzalo, R.; Tesch, P.A.; Lundberg, T.R.; Alkner, B.A.; Rullman, E.; Gustafsson, T. Three months of bed rest induce a residual transcriptomic signature resilient to resistance exercise countermeasures. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 7958–7969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suetta, C.A.; Frandsen, U.; Jensen, L.; Jensen, M.M.; Jespersen, J.G.; Hvid, L.G.; Bayer, M.L.; Petersson, S.J.; Schrøder, H.D.; Andersen, T.J.; et al. Aging Affects the Transcriptional Regulation of Human Skeletal Muscle Disuse Atrophy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standley, R.A.; Distefano, G.; Trevino, M.B.; Chen, E.; Narain, N.R.; Greenwood, B.; Kondakci, G.; Tolstikov, V.V.; A Kiebish, M.; Yu, G.; et al. Skeletal Muscle Energetics and Mitochondrial Function Are Impaired Following 10 Days of Bed Rest in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 75, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibegovic, A.C.; Sonne, M.P.; Højbjerre, L.; Bork-Jensen, J.; Jacobsen, S.; Nilsson, E.; Faerch, K.; Hiscock, N.J.; Mortensen, B.; Friedrichsen, M.; et al. Insulin resistance induced by physical inactivity is associated with multiple transcriptional changes in skeletal muscle in young men. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2010, 299, E752–E763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remels, A.H.V.; Pansters, N.A.; Gosker, H.; Schols, A.M.W.J.; Langen, R.C.J. Activation of alternative NF-κB signaling during recovery of disuse-induced loss of muscle oxidative phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2014, 306, E615–E626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, P.; Liu, H.; He, J.; Zhang, C.; Fan, M.; Chen, X.-P. PGC-1α over-expression suppresses the skeletal muscle atrophy and myofiber-type composition during hindlimb unloading. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 81, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault, J.J.; Jespersen, J.G.; Goldberg, A.L. Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor γ Coactivator 1α or 1β Overexpression Inhibits Muscle Protein Degradation, Induction of Ubiquitin Ligases, and Disuse Atrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 19460–19471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, M.B.; Zhang, X.; Standley, R.A.; Wang, M.; Han, X.; Reis, F.C.G.; Periasamy, M.; Yu, G.; Kelly, D.P.; Goodpaster, B.H.; et al. Loss of mitochondrial energetics is associated with poor recovery of muscle function but not mass following disuse atrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2019, 317, E899–E910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.J.; Rasmussen, B.B. Leucine-enriched nutrients and the regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signalling and human skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2008, 11, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, E.; Arentson-Lantz, E.J.; Lamon, S.; Paddon-Jones, D. Protecting Skeletal Muscle with Protein and Amino Acid during Periods of Disuse. Nutrients 2016, 8, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.E.; Lyon, E.S.; Johnson, M.A.; Vaughan, R.A. Leucine increases mitochondrial metabolism and lipid content without altering insulin signaling in myotubes. Biochimie 2019, 168, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.A.; Gannon, N.P.; Schnuck, J.K.; Lyon, E.S.; Sunderland, K.L.; Vaughan, R.A. Leucine, Palmitate, or Leucine/Palmitate Cotreatment Enhances Myotube Lipid Content and Oxidative Preference. Lipids 2018, 53, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Sato, Y.; Obeng, K.A.; Yoshizawa, F. Acute oral administration of L-leucine upregulates slow-fiber– and mitochondria-related genes in skeletal muscle of rats. Nutr. Res. 2018, 57, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnuck, J.K.; Sunderland, K.L.; Gannon, N.P.; Kuennen, M.R.; Vaughan, R.A. Leucine stimulates PPARβ/δ-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism with enhanced GLUT4 content and glucose uptake in myotubes. Biochimie 2016, 129, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Curry, B.J.; Brown, P.L.; Zemel, M.B. Leucine Modulates Mitochondrial Biogenesis and SIRT1-AMPK Signaling in C2C12 Myotubes. J. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backx, E.M.; Horstman, A.M.; Marzuca-Nassr, G.N.; Van Kranenburg, J.; Smeets, J.S.J.; Fuchs, C.J.; Janssen, A.A.; De Groot, L.C.P.G.M.; Snijders, T.; Verdijk, L.B.; et al. Leucine Supplementation Does Not Attenuate Skeletal Muscle Loss during Leg Immobilization in Healthy, Young Men. Nutrients 2018, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magne, H.; Savary-Auzeloux, I.; Migné, C.; Peyron, M.-A.; Combaret, L.; Rémond, D.; Dardevet, D. Unilateral Hindlimb Casting Induced a Delayed Generalized Muscle Atrophy during Rehabilitation that Is Prevented by a Whey or a High Protein Diet but Not a Free Leucine-Enriched Diet. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, K.L.; A Mettler, J.; Ellison, J.B.; Mamerow, M.M.; Arentson-Lantz, E.; Pattarini, J.M.; Ploutz-Snyder, R.; Sheffield-Moore, M.; Paddon-Jones, D. Leucine partially protects muscle mass and function during bed rest in middle-aged adults1,2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary-Auzeloux, I.; Magne, H.; Migné, C.; Oberli, M.; Breuillé, D.; Faure, M.; Vidal, K.; Perrot, M.; Rémond, D.; Combaret, L.; et al. A Dietary Supplementation with Leucine and Antioxidants Is Capable to Accelerate Muscle Mass Recovery after Immobilization in Adult Rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, R.; Minami, K.; Matsuda, J.; Sawada, N.; Miura, S.; Kamei, Y. Phosphorylation of 4EBP by oral leucine administration was suppressed in the skeletal muscle of PGC-1α knockout mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015, 80, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xiang, L.; Jia, G.; Liu, G.; Zhao, H.; Huang, Z. Leucine regulates slow-twitch muscle fibers expression and mitochondrial function by Sirt1/AMPK signaling in porcine skeletal muscle satellite cells. Anim. Sci. J. 2018, 90, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, R.A.; Garcia-Smith, R.; Gannon, N.P.; Bisoffi, M.; Trujillo, K.A.; Conn, C.A. Leucine treatment enhances oxidative capacity through complete carbohydrate oxidation and increased mitochondrial density in skeletal muscle cells. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.H.; Zeng, L.M.; Li, F.N.; Kong, X.F.; Xu, K.; Guo, Q.P.; Wang, W.L.; Zhang, L.Y. β-hydroxy-β-methyl butyrate promotes leucine metabolism and improves muscle fibre composition in growing pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Q.; Long, B.; Yan, G.; Wang, Z.; Shi, M.; Bao, X.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Dietary leucine supplementation alters energy metabolism and induces slow-to-fast transitions in longissimus dorsi muscle of weanling piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 1222–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Baker, E.; Lee, K.M.; Persinger, A.M.; Hawkins, W.; Puppa, M. Effects of low-dose leucine supplementation on gastrocnemius muscle mitochondrial content and protein turnover in tumor-bearing mice. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.J.; Hossain, T.; Limb, M.C.; Phillips, B.E.; Lund, J.; Williams, J.P.; Brook, M.S.; Cegielski, J.; Philp, A.; Ashcroft, S.; et al. Impact of the calcium form of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate upon human skeletal muscle protein metabolism. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 2068–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.J.; Hossain, T.; Hill, D.S.; Phillips, B.E.; Crossland, H.; Williams, J.; Loughna, P.; Churchward-Venne, T.A.; Breen, L.; Phillips, S.M.; et al. Effects of leucine and its metabolite β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate on human skeletal muscle protein metabolism. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 2911–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standley, R.A.; Distéfano, G.; Pereira, S.L.; Tian, M.; Kelly, O.J.; Coen, P.M.; Deutz, N.E.P.; Wolfe, R.R.; Goodpaster, B.H. Effects of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate on skeletal muscle mitochondrial content and dynamics, and lipids after 10 days of bed rest in older adults. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 123, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alway, S.E.; Pereira, S.L.; Edens, N.K.; Hao, Y.; Bennett, B.T. β-Hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB) enhances the proliferation of satellite cells in fast muscles of aged rats during recovery from disuse atrophy. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Jackson, J.R.; Wang, Y.; Edens, N.; Pereira, S.L.; Alway, S.E. β-Hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate reduces myonuclear apoptosis during recovery from hind limb suspension-induced muscle fiber atrophy in aged rats. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 301, R701–R715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Jia, G.; Liu, G.; Zhao, H.; Huang, Z. Arginine promotes skeletal muscle fiber type transformation from fast-twitch to slow-twitch via Sirt1/AMPK pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 61, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, C.P.V.; Delbin, M.A.; La Guardia, P.G.; Moura, C.S.; Davel, A.P.; Priviero, F.B.M.; Zanesco, A. Improvement of the physical performance is associated with activation of NO/PGC-1α/mtTFA signaling pathway and increased protein expressions of electron transport chain in gastrocnemius muscle from rats supplemented with l-arginine. Life Sci. 2015, 125, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomonosova, Y.N.; Kalamkarov, G.R.; Bugrova, A.E.; Shevchenko, T.F.; Kartashkina, N.L.; Lysenko, E.A.; Shvets, V.I.; Nemirovskaya, T.L. Protective effect of L-arginine administration on proteins of unloaded m. soleus. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2011, 76, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrikanta, A.; Kumar, A.; Govindaswamy, V. Resveratrol content and antioxidant properties of underutilized fruits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Bae, H. An Overview of Stress-Induced Resveratrol Synthesis in Grapes: Perspectives for Resveratrol-Enriched Grape Products. Molecules 2017, 22, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiniak, S.; Aebisher, D.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. Health benefits of resveratrol administration. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2019, 66, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.T.; Mohamed, J.S.; Alway, S.E. Effects of Resveratrol on the Recovery of Muscle Mass Following Disuse in the Plantaris Muscle of Aged Rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas-García, L.; Guitart, M.; Durán, X.; Barreiro, E. Satellite Cells and Markers of Muscle Regeneration during Unloading and Reloading: Effects of Treatment with Resveratrol and Curcumin. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momken, I.; Stevens, L.; Bergouignan, A.; Desplanches, D.; Rudwill, F.; Chery, I.; Zahariev, A.; Zahn, S.; Stein, T.P.; Sebedio, J.L.; et al. Resveratrol prevents the wasting disorders of mechanical unloading by acting as a physical exercise mimetic in the rat. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 3646–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.R.; Ryan, M.J.; Hao, Y.; Alway, S.E. Mediation of endogenous antioxidant enzymes and apoptotic signaling by resveratrol following muscle disuse in the gastrocnemius muscles of young and old rats. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 299, R1572–R1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-J.; Ho, C.-S.; Lee, M.-C.; Ho, C.-S.; Huang, C.-C.; Kan, N.-W. Protective Effects of Resveratrol Supplementation on Contusion Induced Muscle Injury. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; He, Z.; Mao, C.; Shui, X.; Cai, L. Therapeutic Effects of Resveratrol Liposome on Muscle Injury in Rats. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 2377–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alway, S.E.; Myers, M.J.; Mohamed, J.S. Regulation of Satellite Cell Function in Sarcopenia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashida, K.; Kim, S.H.; Jung, S.R.; Asaka, M.; Holloszy, J.O.; Han, D.-H. Effects of Resveratrol and SIRT1 on PGC-1α Activity and Mitochondrial Biogenesis: A Reevaluation. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Cheng, X.; Cui, Y.; Xia, Q.; Yan, X.; Zhang, M.; Lan, G.; Liu, J.; Shan, T.; Huang, Y. Resveratrol regulates skeletal muscle fibers switching through the AdipoR1-AMPK-PGC-1α pathway. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3334–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamdari, N.; Aversa, Z.; Castillero, E.; Gurav, A.; Petkova, V.; Tizio, S.; Hasselgren, P.-O. Resveratrol prevents dexamethasone-induced expression of the muscle atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in cultured myotubes through a SIRT1-dependent mechanism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 417, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.-T.; Yin, Y.; Yang, Y.-J.; Lv, P.-J.; Shi, Y.; Lu, L.; Wei, L. Resveratrol prevents TNF-α-induced muscle atrophy via regulation of Akt/mTOR/FoxO1 signaling in C2C12 myotubes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 19, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.S.; Gubbi, S.; Barzilai, N. Benefits of Metformin in Attenuating the Hallmarks of Aging. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musi, N.; Hirshman, M.F.; Nygren, J.; Svanfeldt, M.; Bavenholm, P.; Rooyackers, O.; Zhou, G.; Williamson, J.M.; Ljunqvist, O.; Efendic, S.; et al. Metformin Increases AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Activity in Skeletal Muscle of Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 2074–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.M.; Treebak, J.T.; Schjerling, P.; Goodyear, L.; Wojtaszewski, J.F.P. Two weeks of metformin treatment induces AMPK-dependent enhancement of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in mouse soleus muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2014, 306, E1099–E1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwa, M.; Egashira, T.; Nakano, H.; Sasaki, H.; Kumagai, S. Metformin increases the PGC-1α protein and oxidative enzyme activities possibly via AMPK phosphorylation in skeletal muscle in vivo. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 101, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; An, H.; Liu, T.; Qin, C.; Sesaki, H.; Guo, S.; Radovick, S.; Hussain, M.; Maheshwari, A.; Wondisford, F.E.; et al. Metformin Improves Mitochondrial Respiratory Activity through Activation of AMPK. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 1511–1523.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Meng, S.; Chang, E.; Beckwith-Fickas, K.; Xiong, L.; Cole, R.N.; Radovick, S.; Wondisford, F.E.; He, L. Low Concentrations of Metformin Suppress Glucose Production in Hepatocytes through AMP-activated Protein Kinase (AMPK). J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 20435–20446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, M.E.; Lyon, E.S.; Vaughan, R.A. Effect of metformin on myotube BCAA catabolism. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 121, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, Y.; Datu, A.; Barnes, B.; Amini-Nik, S.; Jeschke, M.G. Metformin alleviates muscle wasting post-thermal injury by increasing Pax7-positive muscle progenitor cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Wondisford, F.E. Metformin Action: Concentrations Matter. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, P.L.; Delfino, G.B.; Durigan, J.L.Q.; Cancelliero, K.M.; Polacow, M.L.O.; Da Silva, C.A. Metformina minimiza as alterações morfométricas no músculo sóleo de ratos submetidos à imobilização articular. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2008, 14, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Shalaby, S.M.; El-Gendy, J.; Abdelghany, E.M.A. Beneficial effects of metformin on muscle atrophy induced by obesity in rats. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 5677–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langone, F.; Cannata, S.; Fuoco, C.; Barbato, D.L.; Testa, S.; Nardozza, A.P.; Ciriolo, M.R.; Castagnoli, L.; Gargioli, C.; Cesareni, G. Metformin Protects Skeletal Muscle from Cardiotoxin Induced Degeneration. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senesi, P.; Montesano, A.; Luzi, L.; Codella, R.; Benedini, S.; Terruzzi, I. Metformin Treatment Prevents Sedentariness Related Damages in Mice. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, T.; Marinkovic, M.; Rosina, M.; Fuoco, C.; Vumbaca, S.; Gargioli, C.; Castagnoli, L.; Cesareni, G. Metformin Delays Satellite Cell Activation and Maintains Quiescence. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, D.A.; Anderson, E.J.; Iii, J.W.P.; Woodlief, T.L.; Lin, C.-T.; Bikman, B.T.; Cortright, R.N.; Neufer, P.D. Metformin selectively attenuates mitochondrial H2O2 emission without affecting respiratory capacity in skeletal muscle of obese rats. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharath, L.P.; Agrawal, M.; McCambridge, G.; Nicholas, D.A.; Hasturk, H.; Liu, J.; Jiang, K.; Liu, R.; Guo, Z.; Deeney, J.; et al. Metformin Enhances Autophagy and Normalizes Mitochondrial Function to Alleviate Aging-Associated Inflammation. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 44–55.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, H.; Suzuki, N.; Kanno, S.-I.; Kawahara, G.; Izumi, R.; Takahashi, T.; Kitajima, Y.; Osana, S.; Nakamura, N.; Akiyama, T.; et al. AMPK Complex Activation Promotes Sarcolemmal Repair in Dysferlinopathy. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretz, M.; Hébrard, S.; Leclerc, J.; Zarrinpashneh, E.; Soty, M.; Mithieux, G.; Sakamoto, K.; Andreelli, F.; Viollet, B. Metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis in mice independently of the LKB1/AMPK pathway via a decrease in hepatic energy state. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 2355–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatsinki, S.-M.; Buler, M.; Salomäki, H.; Koulu, M.; Pavek, P.; Hakkola, J. Metformin induces PGC-1α expression and selectively affects hepatic PGC-1α functions. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 2351–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.R.; Doran, E.; Halestrap, A.P. Evidence that metformin exerts its anti-diabetic effects through inhibition of complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem. J. 2000, 348, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, A.R.; Laurin, J.L.; Schoenberg, H.M.; Reid, J.J.; Castor, W.M.; Wolff, C.A.; Musci, R.V.; Safairad, O.D.; Linden, M.A.; Biela, L.M.; et al. Metformin inhibits mitochondrial adaptations to aerobic exercise training in older adults. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, R.G.; Dungan, C.M.; Long, D.E.; Tuggle, S.C.; Kosmac, K.; Peck, B.D.; Bush, H.M.; Tezanos, A.G.V.; McGwin, G.; Windham, S.T.; et al. Metformin blunts muscle hypertrophy in response to progressive resistance exercise training in older adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial: The MASTERS trial. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.N.; Hussein, U.K.; Yassa, H.D.; Hassan, S.S.; Rashed, L.A. Synergistic actions of vitamin D and metformin on skeletal muscles and insulin resistance of type 2 diabetic rats. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 5768–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Bruckbauer, A.; Zemel, M.B. Activation of the AMPK/Sirt1 pathway by a leucine–metformin combination increases insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle and stimulates glucose and lipid metabolism and increases life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Metabolism 2016, 65, 1679–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Bruckbauer, A.; Li, F.; Cao, Q.; Cui, X.; Wu, R.; Shi, H.; Zemel, M.B.; Xue, B. Leucine amplifies the effects of metformin on insulin sensitivity and glycemic control in diet-induced obese mice. Metabolism 2015, 64, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frendo-Cumbo, S.; MacPherson, R.E.K.; Wright, D.C. Beneficial effects of combined resveratrol and metformin therapy in treating diet-induced insulin resistance. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemel, M.B.; Bruckbauer, A. Synergistic effects of metformin, resveratrol, and hydroxymethylbutyrate on insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2013, 6, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bruckbauer, A.; Banerjee, J.; Fu, L.; Li, F.; Cao, Q.; Cui, X.; Wu, R.; Shi, H.; Xue, B.; Zemel, M.B. A Combination of Leucine, Metformin, and Sildenafil Treats Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Steatohepatitis in Mice. Int. J. Hepatol. 2016, 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalasani, N.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Rinella, M.; Middleton, M.S.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Barritt, A.S.; Kolterman, O.; Flores, O.; Alonso, C.; Iruarrizaga-Lejarreta, M.; et al. Randomised clinical trial: A leucine-metformin-sildenafil combination (NS-0200) vs. placebo in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemel, M.B.; Kolterman, O.; Rinella, M.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Flores, O.; Barritt, A.S.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Chalasani, N. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Leucine-Metformin-Sildenafil Combination (NS-0200) on Weight and Metabolic Parameters. Obesity 2018, 27, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Age | Cell Type/Tissue | Additional Intervention | Dosage and Route of Administration | Length of Treatment | Influence on PGC-1α | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leucine | Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 2 mM in medium | 1 d | ↑ mRNA | 51 |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 1 and 2 mM in medium | 1 d | ↑ mRNA | 52 | |

| Rat | 5 wks | Soleus EDL | — | 135 mg/100 g BW via oral gavage | 1 h and 3 h | ↑ mRNA | 53 | |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 20 mM in medium | 1 h | ↑ mRNA | 53 | |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 2 mM in medium | 1 d | ↑ mRNA ↑ protein | 54 | |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 0.5 mM in medium | 2 d | ↑ mRNA | 55 | |

| Pig | — | Primary myotubes | — | 2 mM in medium | 3 d | ↑ protein | 61 | |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 0.5 mM in medium | 1 d | ↑ protein | 62 | |

| Pig | 11.4 wks (80 d) | Longissimus Dorsi Soleus | — | 1.25% of diet | 45 d | ↔ mRNA | 63 | |

| Pig | 7 wks | Longissimus Dorsi | — | 1.66% and 2.1% of diet | 14 d | ↔ protein | 64 | |

| Mouse | 9–10 wks | Gastrocnemius | Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) injection | 5% w/w supplemented in diet | 28 d | ↔ protein (control) ↑ protein (LLC group) | 65 | |

| HMB | Pig | 11.4 wks (80 d) | Longissimus Dorsi Soleus | — | 0.62% of diet | 45 d | ↔ mRNA | 63 |

| Human | 66–67 yrs | Vastus Lateralis | 10 d bed rest | 3 g/d oral supplementation | 15 d | ↑ protein | 43 | |

| Arginine | Mouse | 3 wks | Tibialis Anterior | — | 0.25, 0.5 and 1% supplemented in diet | 42 d | ↑ mRNA ↑ protein | 71 |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 0.5 mM in medium | 3 d | ↑ mRNA | 71 | |

| Rat | 9–10 wks | Gastrocnemius | 8 wk progressive treadmill running | 62.5 mg/mL/d via oral gavage | 56 d | ↔ protein (control) ↑ protein (exercise group) | 72 | |

| Resveratrol | Rat | 32 mo | Plantaris | 14 d hindlimb unloading and 14 d reloading | 125 mg/kg/d via oral gavage and 0.05% supplemented in diet | 35 d | ↑ protein during unloading and reloading | 77 |

| Rat | 8 wks | Soleus | 14 d hindlimb unloading | 400 mg/kg/d via oral gavage | 42 d | ↔ mRNA ↑ protein (unloaded group) | 79 | |

| Rat | 4–5 wks | Soleus Gastrocnemius | — | 4 g/kg of diet | 56 d | ↔ protein | 84 | |

| Mouse | — | Triceps | HFD with resveratrol | 4 g/kg of diet | 56 d | ↔ protein | 84 | |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 20 μM in medium | 6 h/d for 3 d | ↑ protein | 84 | |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 1, 5, and 10 μM in medium | 1 d | ↔ protein | 84 | |

| Mouse | 15 wks | Extensor Digitorum Longus Soleus | — | 400 mg/kg/d via oral gavage | 84 d | ↑ mRNA ↑ protein | 85 | |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 20 μM in medium | — | ↑ mRNA ↑ protein | 85 | |

| Metformin | Rat | 10 wks | Soleus Red gastrocnemius White gastrocnemius | — | 1% of diet | 14 d | ↑ protein | 91 |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 2 mM in medium | 4, 8, 12 and 24 h | ↑ mRNA (only at 24 h) ↑ protein (all timepoints) | 94 | |

| Mouse | — | C2C12 myotubes | — | 30 μM in medium | 4, 8, 12 and 24 h | ↔ mRNA or protein (all timepoints) | 94 | |

| Metformin+Vitamin D | Rat | 6 wks | Gastrocnemius | Two weeks HFD with 1 IP injection of STZ to induce T2D | Metformin: 100 mg/kg BW via oral gavage Vitamin D: 0.5 μg/kg BW via IP injection | 56 d | ↑ mRNA (T2D group) | 110 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrocelli, J.J.; Drummond, M.J. PGC-1α-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches to Enhance Muscle Recovery in Aging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228650

Petrocelli JJ, Drummond MJ. PGC-1α-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches to Enhance Muscle Recovery in Aging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228650

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrocelli, Jonathan J., and Micah J. Drummond. 2020. "PGC-1α-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches to Enhance Muscle Recovery in Aging" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228650

APA StylePetrocelli, J. J., & Drummond, M. J. (2020). PGC-1α-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches to Enhance Muscle Recovery in Aging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228650