Moral Disengagement as a Moderating Factor in the Relationship between the Perception of Dating Violence and Victimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Dating Violence: Perception of Aggressive Behavior from the Victims’ Point of View

1.2. Influence of Moral Disengagement on Violent Behavior in Teenage Dating

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

- Dating Violence Questionnaire (Cuestionario de Violencia de Novios, CUVINO) [32]. This questionnaire consists of a total of 61 items grouped into three thematic blocks. The first of these blocks is subdivided into two: one is designed to measure the frequency of the violence, and the other, the degree of tolerance that this behavior provokes or might provoke in adolescents. In both cases, a 5-point Likert scale is used, but with different anchors—in the first case (frequency) from “Never” to “Almost always”, and in the second (tolerance) from “None” to “A lot”. The pairs of scores obtained in this first block can be grouped into a total of 8 sub-scales: detachment (“Is a good student, but is always late at meetings, does not fulfill his/her promises, and is irresponsible”), humiliation (“Ridicules your way of expressing yourself”), sexual (“You feel forced to perform certain sexual acts”), sexual (“You feel forced to perform certain sexual acts”), coercion (“Threatens to commit suicide or hurt himself/herself if you leave him/her”), physical (“Has thrown blunt instruments at you”), gender (“Has ridiculed or insulted women or men as a group”), emotional punishment (“Refuses to give you support or affection as punishment”), and instrumental punishment (“Has stolen from you”). The second block focuses on the adolescents’ perception of the profile of the victim, obtaining three scores: fearful, trapped, and mistreated. Finally, the third block delves into the victimization relationship, addressing such aspects as the duration of the relationship, number of attempts to break up, etc. The match of this questionnaire to the study’s samples is evidenced by the reliability indices (Cronbach’s alpha) that were obtained, which ranged between 0.66 and 0.83 for the different violence sub-scales.

- Mechanisms of Moral Disengagement Scale (MMDS) [33]. This questionnaire has 32 items that allow one to obtain 8 partial scores which correspond to the 8 factors of moral disengagement: moral justification, euphemistic language, advantageous comparison, displacement of responsibility, diffusion of responsibility, distortion of consequences, attribution of blame, and dehumanization. The scale used is a Likert scale with 5 anchor points ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. The overall internal consistency of the test (Cronbach’s alpha) is 0.74, and, the reliability of the 8 mechanisms range between 0.72 and 0.81. Finally, these 8 mechanisms can be grouped into 4 dimensions or factors: behavioral locus (0.75), outcome locus (0.78), agency locus (0.79), and recipients locus (0.81).

2.3. Procedure

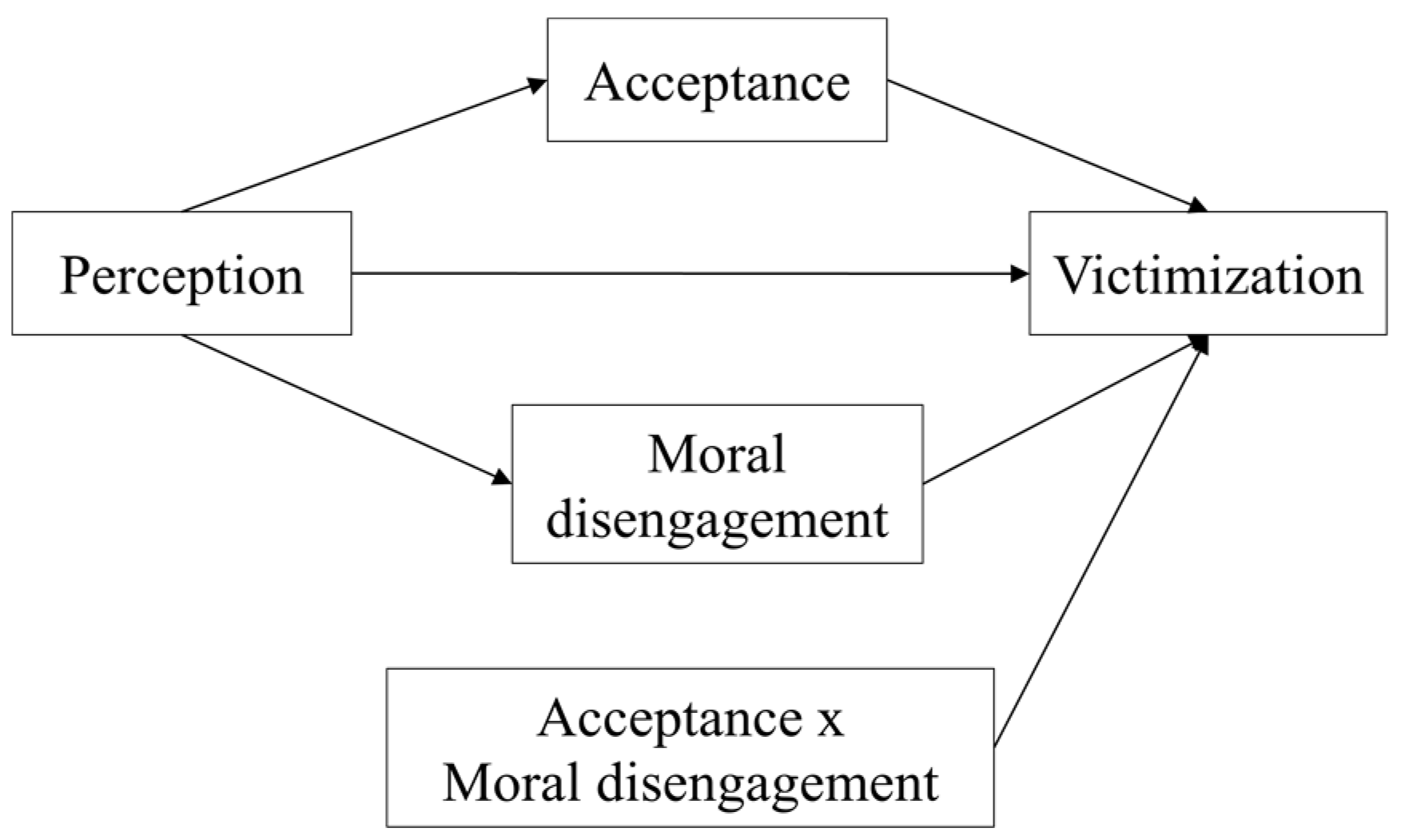

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, E. Prevention of and interventions for dating and sexual violence in adolescence. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 64, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Garay, F.; Carrasco Ortiz, M.A.; García-Rodríguez, B. Desconexión moral y violencia en las relaciones de noviazgo de adolescentes y jóvenes: Un estudio exploratorio. Rev. Argent. De Clínica Psicol. 2019, 28, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dalfo-Pibernat, A.; Feijoo-Cid, M. Dating violence is an important issue in nursing education. Int. Nursrev. 2017, 64, 329–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, J.A.; Lehrer, E.L.; Koss, M.P. Sexual and dating violence among adolescents and young adults in Chile: A review of findings from a survey of university students. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Sakalli-Ugurlu, N.; Ferreira, M.C.; Souza, M.A.D. Ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward wife abuse in Turkey and Brazil. Psychol. Women Q. 2002, 26, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.C.; Expósito, F.; Moya, M. Negative reactions of men to the loss of power in gender relations: Lilith vs. Eve. Eur. J. Psych. Appl. Leg. Context 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Obeid, N.; Chang, D.F.; Ginges, J. Beliefs about wife beating: An exploratory study with Lebanese students. Violence Ag. Women 2010, 16, 691–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, F. La Educación Sexual; Biblioteca Nueva: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fuertes, A.A.; Fuertes, A.; Fernández-Rouco, N.; Orgaz, B. Past aggressive behavior, costs and benefits of aggression, romantic attachment, and teen dating violence perpetration in Spain. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 100, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, D.; Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M.; Crago, R.V. Risk factors for dating violence versus cohabiting violence: Results from the third generation of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2016, 26, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.S.; Connolly, J.; Pepler, D.; Craig, W.; Laporte, L. Risk models of dating aggression across different adolescent relationships: A developmental psychopathology approach. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigvert, L.; Gelsthorpe, L.; Soler-Gallart, M.; Flecha, R. Girls’ perceptions of boys with violent attitudes and behaviours, and of sexual attraction. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J. Radical Love: A Revolution for the 21st Century; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Soler-Gallart, M. Achieving Social Impact: Sociology in the Public Sphere; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- González, R.; Santana, J.D. La violencia en parejas jóvenes. Psicothema 2001, 13, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, H.L.M.; Foshee, V.A.; Niolon, P.H.; Reidy, D.E.; Hall, J.E. Gender role attitudes and male adolescent dating violence perpetration: Normative beliefs as moderators. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Selective activation and disengagement of moral control. J. Soc. Issues 1990, 46, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lei, L.; Yang, J.; Gao, L.; Zhao, F. Moral disengagement as mediator and moderator of the relation between empathy and aggression among Chinese male juvenile delinquents. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Pers. Soc. Psychol Rev. 1999, 3, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of thought and Action; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Feiring, C.; Deblinger, E.; Hoch-Espada, A.; Haworth, T. Romantic relationship aggression and attitudes in high school students: The role of gender, grade, and attachment and emotional styles. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tata, J. She said, he said. The influence of remedial accounts on third-party judgments of coworker sexual harassment. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, B.A. Sexual harassment and masculinity: The power and meaning of “girl watching”. Gend. Soc. 2002, 16, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinet, M.T.; Li, F.; Berg, T. Early childhood maltreatment and trajectories of behavioral problems: Exploring gender and racial differences. Child. Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Gao, L.; Yang, J.; Lei, L.; Wang, C. Childhood maltreatment and Chinese adolescents’ bullying and defending: The mediating role of moral disengagement. Child. Abus. Negl. 2017, 69, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontaine, R.G.; Fida, R.; Paciello, M.; Tisak, M.S.; Caprara, G.V. The mediating role of moral disengagement in the developmental course from peer rejection in adolescence to crime in early adulthood. Psychol. Crime Law 2014, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, S.; Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E.; Malti, T.; Hymel, S. Moral reasoning and emotion attributions of adolescent bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 30, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, K.R.; Bussey, K. Individual and collective moral influences on intervention in cyberbullying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 74, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.; Bussey, K. The selectivity of moral disengagement in defenders of cyberbullying: Contextual moral disengagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Gordillo, I.; Fernández-Antelo, I. Analysis of moral disengagement as a modulating factor in adolescents’ perception of cyberbullying. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Lei, L. Perceived school climate and adolescents’ bullying perpetration: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and peers’ defending. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Franco, L.; López-Cepero, J.; Rodríguez, F.J.; Bringas, C.; Estrada, C.; Antuña, M.A.; Quevedo, R. Labeling dating abuse: Undetected abuse among Spanish adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2012, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fermani, A.; Bongelli, R.; Canestrari, C.; Muzi, M.; Riccioni, I.; Burro, R. “Old wine in a new bottle”. Depression and romantic relationship in Italian emerging adulthood: The moderating effect of gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, W.; Simon, V.A. Actor and partner effects of adolescents’ romantic working models and styles on interactions with romantic partners. Child. Dev. 2006, 77, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, D.A.; Valdez, C.E.; Engle, J.L.; Menghrajani, E. Attachment anxiety as a risk factor for subsequent intimate partner violence victimization: A 6-month prospective study among college women. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 1410–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza, J.A.D. Violencia en las relaciones de noviazgo: Una revisión de estudios cualitativos. Apunt. Psicol. 2018, 35, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Viki, G.T.; Abrams, D.; Hutchison, P. The “true” romantic: Benevolent sexism and paternalistic chivalry. Sex. Roles 2003, 49, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molidor, C.; Tolman, R.M. Gender and contextual factors in adolescent dating violence. Violence Ag. Women 1998, 4, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.E.; Temple, J.R.; Weston, R.; Le, V.D. Witnessing interparental violence and acceptance of dating violence as predictors for teen dating violence victimization. Violence Ag. Women 2016, 22, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Aliri, J.; Martínez-Valderrey, V. Justificación de la violencia durante la adolescencia: Diferencias en función de variables sociodemográficas. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 6, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, M.; García, A.; Cuetos, G.; Sirvent, C. Violencia en el noviazgo, dependencia emocional y autoestima en adolescentes y jóvenes españoles. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud. 2017, 8, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Moral, M.V.; Sirvent, C. Dependencia afectiva y género: Perfil sintomático diferencial en dependientes afectivos españoles. Interam. J. Psychol. 2009, 43, 230–240. [Google Scholar]

- Menesini, E.; Nocentini, A. Comportamenti aggressivi nelle prime esperienze sentimentali in adolescenza. G. Ital. Psicol. 2008, 35, 407–434. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, H.H.; Herrera, V.M.; Stuewig, J. Abusive males and abused females in adolescent relationships: Risk factor similarity and dissimilarity and the role of relationship seriousness. J. Fam. Violence 2003, 18, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.B. Violencia en el noviazgo: Diferencias de género. Inf. Psicológicos 2016, 16, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga, X.B. Joking violence among highly committed individuals. J. Interpers. Violence 2002, 17, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.L. Nuevos tiempos, viejas preguntas sobre el amor: Un estudio con adolescentes. Posgrado Y Soc. 2007, 7, 50–70. [Google Scholar]

- Castelló, J. Dependencia emocional. Características y tratamiento. abusers. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2005, 1, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey, K.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Raman, A. The role of moral disengagement and self-efficacy in cyberbullying. J. Sch. Violence 2015, 14, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Freeman, D.; Reed, I.I.; Lim, V.K.; Felps, W. Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, P.; Lei, L. Trait anger and cyberbullying among young adults: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and moral identity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y. Effects of perceived descriptive norms on corrupt intention: The mediating role of moral disengagement. Int. J. Psychol. 2019, 54, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Garay, F.; Carrasco, M.A.; García-Rodríguez, B. Moral disengagement and violence in adolescent and young dating relationships: A correlational study. Rev. Argent. Clín. Psicol. 2015, 25, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Moral Educ. 2002, 31, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.C.; Fite, P.J.; Torres, E.D.; Stuart, G.L.; Temple, J.R. Bidirectional associations between acceptability of violence and intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. Psychol. Violence 2019, 9, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Frequently | Usually | |

|---|---|---|

| Victims | 395 (15.33%) | 91 (1.59%) |

| Detachment | 258 (65.31%) | 50 (54.9%) |

| Humiliation | 82 (20.75%) | 10 (10.98%) |

| Sexual | 73 (18.48%) | 20 (21.97%) |

| Coercion | 141 (35.69%) | 40 (43.95%) |

| Physical | 34 (8.60%) | 9 (9.89%) |

| Gender-Based | 90 (22.78%) | 19 (20.87%) |

| Emotional Punishment | 188 (47.59%) | 42 (46.15%) |

| Instrumental | 42 (10.63%) | 6 (6.59%) |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | - | ||||||

| Gender | 0.16 | - | |||||

| Age | 0.15 | 0.04 | - | ||||

| Intensity | 0.22 * | 0.11 | 0.09 | - | |||

| Perception | 0.48 *** | 0.19 * | 0.14 | 0.21 * | - | ||

| Acceptance | −0.44 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.20 * | −0.19 * | −0.21 * | - | |

| Moral disengagement | 0.33 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.26 ** | 0.61 *** | - |

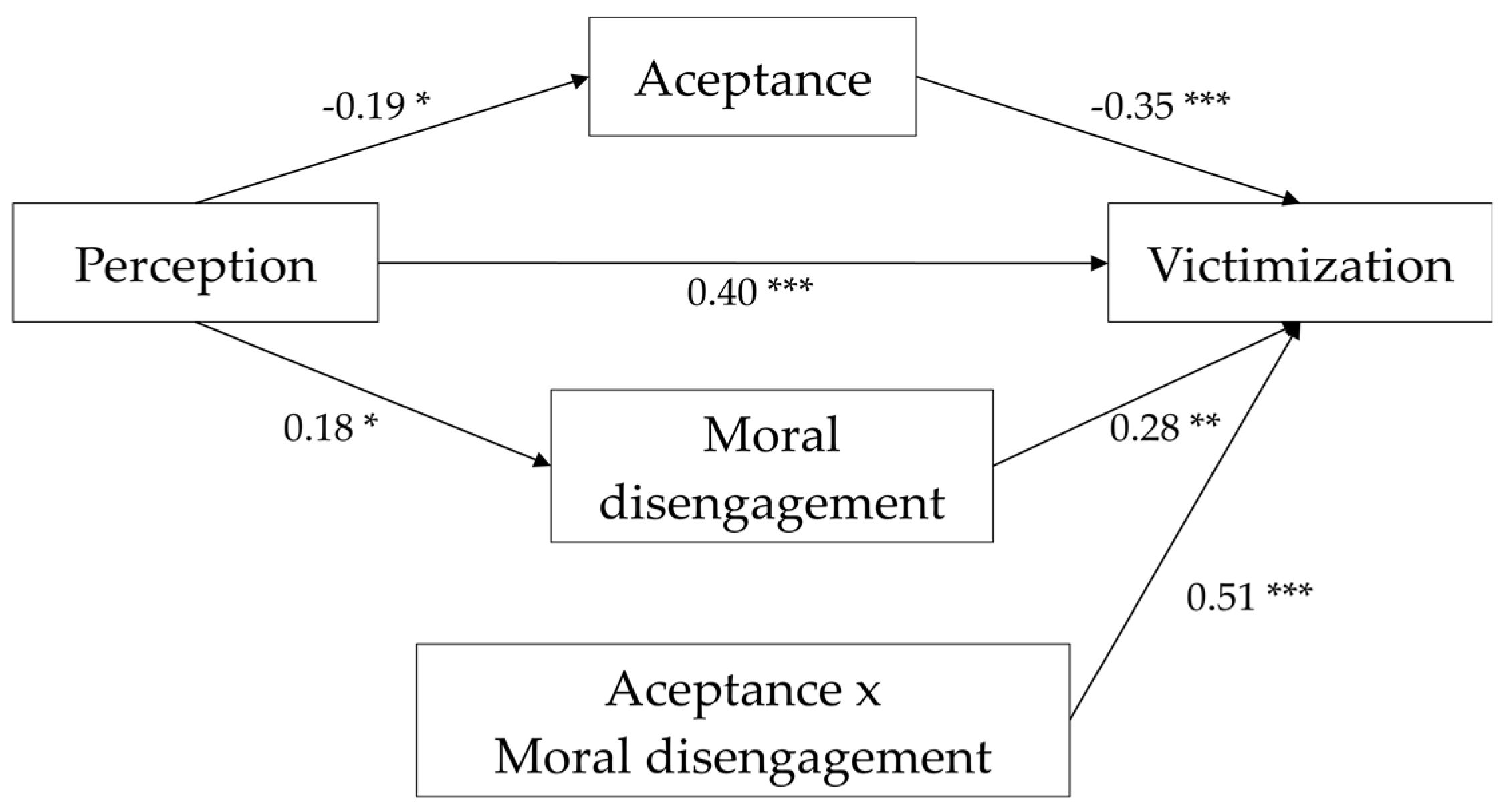

| Variables | Model 1 Mediator: Acceptance | Model 2 Mediator: Moral Disengagement | Model 3 Dependent Variable: Victimization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | SE | β | SE | Β | SE | |

| Gender | 0.24 ** | 0.04 | 0.20 ** | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Age | 0.17 * | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Intensity | −0.16 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.17 * | 0.02 |

| Perception | −0.19 * | 0.04 | 0.18 * | 0.03 | 0.40 *** | 0.04 |

| Acceptance | −0.35 *** | 0.06 | ||||

| Moral disengagement | 0.28 ** | 0.03 | ||||

| Acceptance x Moral disengagement | 0.51 *** | 0.05 | ||||

| R2 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.19 | |||

| Adj. R2 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.16 | |||

| F | 26.14 | 12.35 | 17.83 | |||

| β | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct effects of IV on mediators Perception →Acceptance Perception → Moral disengagement | −0.19 *** 0.17 ** | 0.04 0.02 |

| Direct effects of mediators on DV Acceptance → Victimization Moral disengagement → Victimization | −0.39 *** 0.28 *** | 0.05 0.05 |

| Direct Effects of IV on DV Perception → Victimization | 0.41 *** | 0.04 |

| R2 | 0.14 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.11 | |

| F | 18.36 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuadrado-Gordillo, I.; Fernández-Antelo, I.; Martín-Mora Parra, G. Moral Disengagement as a Moderating Factor in the Relationship between the Perception of Dating Violence and Victimization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145164

Cuadrado-Gordillo I, Fernández-Antelo I, Martín-Mora Parra G. Moral Disengagement as a Moderating Factor in the Relationship between the Perception of Dating Violence and Victimization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):5164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145164

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuadrado-Gordillo, Isabel, Inmaculada Fernández-Antelo, and Guadalupe Martín-Mora Parra. 2020. "Moral Disengagement as a Moderating Factor in the Relationship between the Perception of Dating Violence and Victimization" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 5164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145164

APA StyleCuadrado-Gordillo, I., Fernández-Antelo, I., & Martín-Mora Parra, G. (2020). Moral Disengagement as a Moderating Factor in the Relationship between the Perception of Dating Violence and Victimization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145164