Co-Creating Recommendations to Redesign and Promote Strength and Balance Service Provision

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Co-Creation Workshops

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Profile

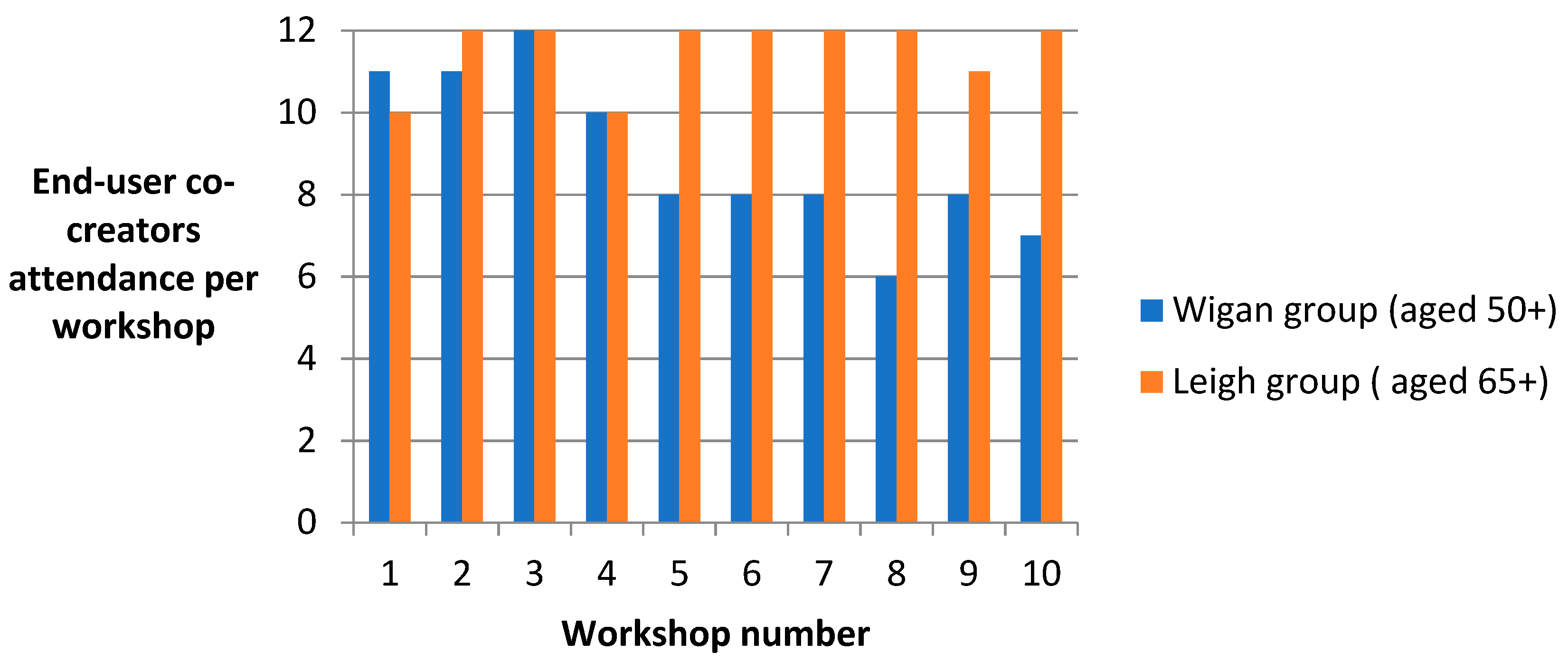

3.2. Attendance and Retention

3.3. Recommendations for Change and Improvement

3.3.1. Localised Strategies for Awareness Raising Recommendations

Promote the UK Physical Activity Guidelines and Locally Available Physical Activity Opportunities

Encourage Health and Social Care Services to Play an Active Role in Promoting the UK Physical Activity Guidelines

Working Collaboratively to Implement Recommendations over Time

3.3.2. Recruitment Recommendations

Recruit, Train and Support Volunteer Champions to Provide a Physical Activity Outreach Programme

Employ Staff and Volunteers as Older ‘Ambassadors’ in Leisure Centres to Promote Age-Friendly Developments

3.3.3. Accessibility Recommendations

Produce Accessible Physical Activity Information Including the Benefits of Strength and Balance

Explore Different Pricing Options and Incentives for Older Adults’ Physical Activity Participation

Provide Simple Exercises That People Can Do at Home or in Community Settings

Improve the Accessibility of Strength and Balance Programmes

3.3.4. Evaluation Recommendations

Monitor and Evaluate Strength and Balance Programmes and Their Impact on Wider Community Awareness

Satisfaction of Engaging in the Co-Creation Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Health, Physical Activity, Health Improvement and Protection. Start Active, Stay Active: A Report on Physical Activity from the Four Home Countries’ Chief Medical Officers. 2011. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216370/dh_128210.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Public Health England. Muscle and Bone Strengthening and Balance Activities for General Health Benefits in Adults and Older Adults. Summary of a Rapid Evidence Review for the UK’s Chief Medical Officers’ Update of the Physical Activity Guidelines. 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/721874/MBSBA_evidence_review.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Strain, T.; Fitzsimons, C.; Kelly, P.; Mutrie, N. The forgotten guidelines: cross-sectional analysis of participation in muscle strengthening and balance and co-ordination activities by adults and older adults in Scotland. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skelton, D.A.; Mavroeidi, A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are more important? JFSF 2018, 3, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, D.A.; Mavroeidi, A. Which strength and balance activities are safe and efficacious for individuals with specific challenges (osteoporosis, vertebral fractures, frailty, dementia): A Narrative review. JFSF 2018, 3, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillsdon, M.; Foster, C. What are the health benefits of muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities across life stages and specific health outcomes? JFSF 2018, 3, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Armstrong, M.E.G. What type of physical activities are effective in developing muscle and bone strength and balance? JFSF 2018, 3, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethancourt, H.J.; Rosenberg, D.E.; Beatty, T.; Arterburn, D.E. Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity programme use among older adults. Clin. Med. Res. 2014, 12, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.R.; Stathokostas, L.; Young, B.W.; Wister, A.V.; Chau, S.; Clark, P.; Duggan, M.; Mitchell, D.; Nordland, P. Development of a physical literacy model for older adults—A consensus process by the collaborative working group on physical literacy for older Canadians. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, L.D.; Peters, A.; Chalmers, N.; Gawler, S.; Henderson, C.; Hooper, J.; Laventure, R.M.E.; McLean, L.; Skelton, D.A. Views of older adults and allied health professionals on the acceptability of the Functional Fitness MOT: A Mixed-Method Feasibility Study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 1815–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, P.; Robert, G. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, R.; Lisby, M.; Hockey, P.M.; Levtzion-Korach, O.; Salzberg, C.A.; Efrati, N.; Lipsitz, S.; Bates, D.W. The patient satisfaction chasm: the gap between hospital management and frontline clinicians. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 3, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Chastin, S.F.M. On behalf of the GrandStand Research Group. Co-creating a tailored public health intervention to reduce older adults’ sedentary behaviour. Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, V.S.; Slevitch, L.; Larzelere, R.; Morosan, C.; Kwun, D.J. Effects of psychological ownership on students’ commitment and satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 25, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, H. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 2011, 11, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Altenburg, T.M.; Cardon, G.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Verloigne, M.; Chastin, S.F.M. And on behalf of the GrandStand, Safe Step and Teenage Girls on the Move Research Groups. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. RIAE 2019, 5, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, A.F. Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Problem Solving; 721 Third Review; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J.A. Avoiding traps in member checking. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 1102–1113. [Google Scholar]

- Schreirer, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Home Exercise Booklets. Free to Download. Available online: https://www.laterlifetraining.co.uk/llt-home-exercise-booklets/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Strong and Balanced Offer Full Report to Wellcome Trust. Available online: https://edshare.gcu.ac.uk/4781/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Fredriksson, S.V.; Alley, S.J.; Rebar, A.L.; Hayman, M.; Vandelanotte, C.; Schoeppe, S. How are different levels of knowledge about physical activity associated with physical activity behaviour in Australian adults? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, A.; Littlewood, C.; McLean, S.; Kilner, K. Physiotherapy and physical activity: a cross-sectional survey exploring physical activity promotion, knowledge of physical activity guidelines and the physical activity habits of UK physiotherapists. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2017, 3, e000290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, R.; Chapman, T.; Brannan, M.G.; Varney, J. GPs’ knowledge, use, and confidence in national physical activity and health guidelines and tools: a questionnaire-based survey of general practice in England. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, e668–e675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, E.; Farrier, K.; Hill, K.D.; Codde, J.; Airey, P.; Hill, A.M. Effectiveness of peers in delivering programs or motivating older people to increase their participation in physical activity: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Choi, E.; Morrow-Howell, N. Organizational support and volunteering benefits for older adults. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley-Hague, H.; Horne, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Todd, C. Older adults’ uptake and adherence to exercise classes: instructors’ perspectives. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2016, 24, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perracini, M.R.; Franco, M.R.C.; Ricci, N.A.; Blake, C. Physical activity in older people - Case studies of how to make change happen. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 31, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiney, H.; Keall, M.; Machado, L. Physical activity prevalence and correlates among New Zealand older adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2018, 26, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, R.J.; Čukić, I.; Deary, I.J.; Gale, C.R.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Dall, P.M.; Skelton, D.A.; Der, G. On behalf of the Seniors USP Team. Relationships between socioeconomic position and objectively measured sedentary behaviour in older adults. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Fox, A. Menu labels, for better, and worse? Exploring socio-economic and race-ethnic differences in menu label use in a national sample. Appetite 2018, 128, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witman, A.; Acquah, J.; Alva, M.; Hoerger, T.; Romaire, M. Medicaid incentives for preventing chronic disease: effects of financial incentives for smoking cessation. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 53, 5016–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.; Bettencourt, A.F. Financial incentives for promoting participation in a school-based parenting program in low-income communities. Prev. Sci. 2019, 15, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, B.; Wiklund, M.; Janols, R.; Lindgren, H.; Lundin-Olsson, L.; Skelton, D.A.; Sandlund, M. ‘Managing pieces of a personal puzzle’—Older people’s experiences of self-management falls prevention exercise guided by a digital program or a booklet. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, H. Physical Activity—At Our Age. Health Education Authority, London Qualitative Research among People over the Age of 50; Health Education Authority: London, UK, 1997; Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/physical-activity-at-our-age-qualitative-research-among-people-over-the-age-of-50/oclc/37808310 (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee. Older People and Employment; UK Government: London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmwomeq/359/359.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

| Workshop | Key Discussion Areas | Additional Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1: Induction/overview | Introductions from facilitators and participants | Programme paperwork and questionnaires |

| Week 2: Research and evidence | Physical activity guidelines | Expectations of the programme |

| Week 3: Research and evidence | Strength and balance and ageing | Functional Fitness MOT tests [10] |

| Week 4: Research and evidence | Barriers and enablers for being more active | Practical ideas for incorporating strength and balance |

| Week 5: Research and evidence | Assessing the value of activity choices for strength, balance or other outcomes | Supplemented by an overview of the leisure offer (with emphasis on strength and balance activities) |

| Week 6: Practical experience of programmes on offer | Opportunity to try out activities and find out more | |

| Week 7: Identifying areas for improvement | Exploring ideas and recommendations for local service provision | Exploring ideas and recommendations for promoting services and guidelines |

| Week 8: Exploring how groups can influence change | Exploring opportunities to influence positive change through the programme | Planning for stakeholder session and prioritising key recommendations/learning |

| Week 9: Presentation to external stakeholders | Sharing recommendations and ‘light bulb’ moments | Personal journeys and contributions |

| Week 10: Reflections on programme and next steps | Feedback on stakeholder event and final matters to raise | Feedback on programme overall and plans moving forward (personal/as a group) |

| Characteristics | Number (N) |

|---|---|

| Gender, N (%) | |

| Female | 14 (58) |

| Male | 10 (42) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |

| White British | 22 (92) |

| Black British | 1 (4) |

| Asian British | 1 (4) |

| Living with chronic health condition, N (%) | 14 (58) |

| Living with a disability | 12 (50) |

| Physical activity levels, N (%) | |

| Inactive (less than 30 min of physical activity per week) | 5 (21) |

| Fairly active (30–149 min of physical activity per week) | 14 (58) |

| Active (150 min of physical activity per week or more) | 5 (21) |

| Socio-economic status N (%) | |

| Quintile 1 (Least affluent) | 0 (0) |

| Quintile 2 | 2 (8) |

| Quintile 3 | 7 (29) |

| Quintile 4 | 6 (25) |

| Quintile 5 (Most affluent) | 7 (29) |

| Not reported | 2 (8) |

| Theme | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Localised strategies for awareness raising | Promote the UK Physical Activity Guidelines and locally available physical activity opportunities Encourage health and social care services to play an active role in promoting the UK Physical Activity Guidelines Working collaboratively to implement recommendations over time |

| Recruitment | Recruit, train and support volunteer champions to provide a physical activity outreach programme Employ staff and volunteers as older ‘Ambassadors’ in leisure centres to promote age-friendly developments |

| Accessibility | Produce accessible physical activity information, including the benefits of strength and balance Explore different pricing options and incentives for older adults’ physical activity participation Provide simple exercises that people can do at home or in community settings |

| Evaluation | Improve the accessibility of strength and balance programmes Monitor and evaluate strength and balance programmes and their impact on wider community awareness |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leask, C.F.; Colledge, N.; Laventure, R.M.E.; McCann, D.A.; Skelton, D.A. Co-Creating Recommendations to Redesign and Promote Strength and Balance Service Provision. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173169

Leask CF, Colledge N, Laventure RME, McCann DA, Skelton DA. Co-Creating Recommendations to Redesign and Promote Strength and Balance Service Provision. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(17):3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173169

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeask, Calum F, Nick Colledge, Robert M E Laventure, Deborah A McCann, and Dawn A Skelton. 2019. "Co-Creating Recommendations to Redesign and Promote Strength and Balance Service Provision" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 17: 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173169

APA StyleLeask, C. F., Colledge, N., Laventure, R. M. E., McCann, D. A., & Skelton, D. A. (2019). Co-Creating Recommendations to Redesign and Promote Strength and Balance Service Provision. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173169