Pathways to Increasing Adolescent Physical Activity and Wellbeing: A Mediation Analysis of Intervention Components Designed Using a Participatory Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Measures

2.5. Outcomes

2.5.1. Physical Activity (Accelerometry)

2.5.2. Wellbeing

2.6. Exposures: Engagement with Intervention Components

2.7. Potential Mediators

2.8. Potential Confounders

2.9. Statistical Analysis

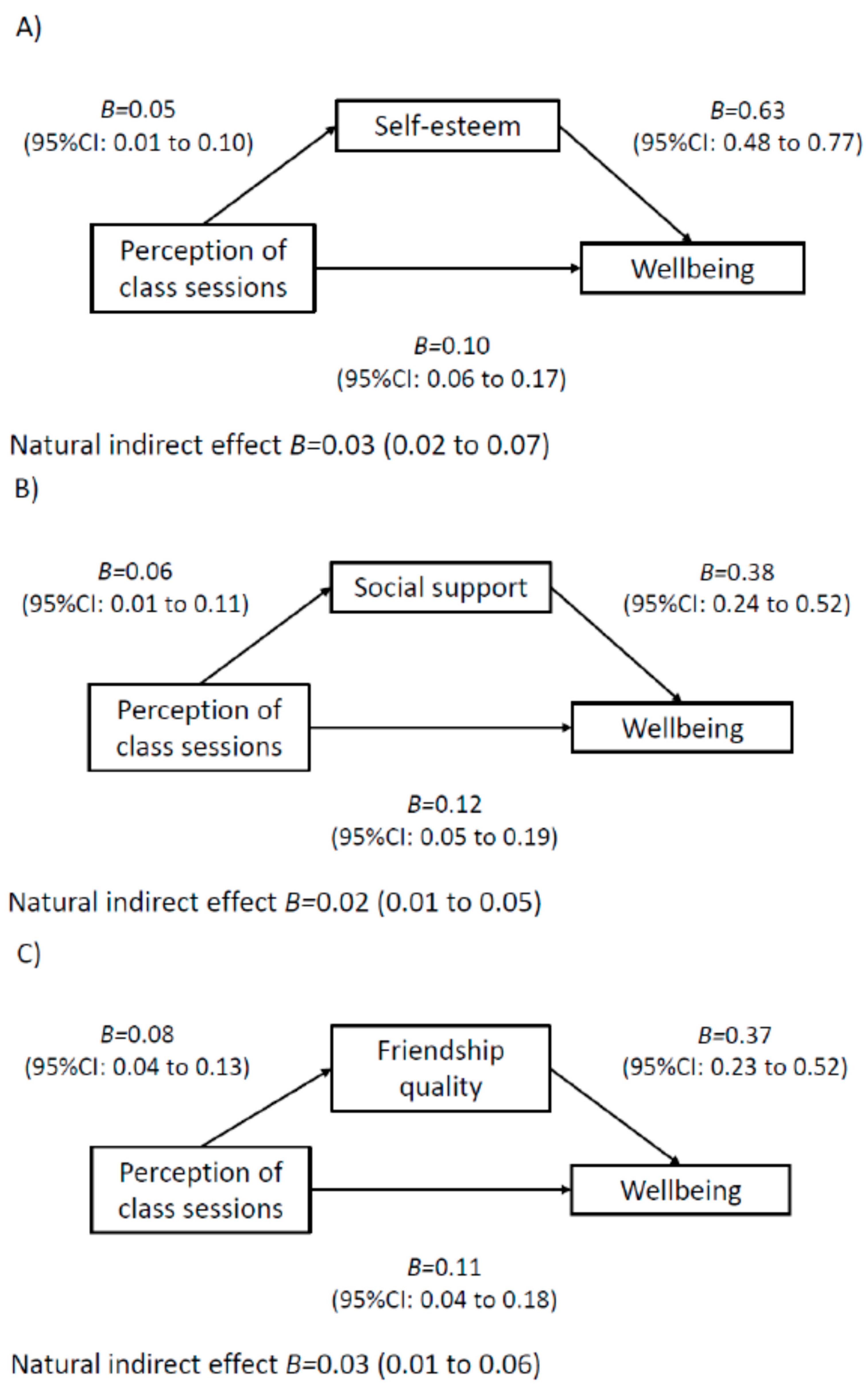

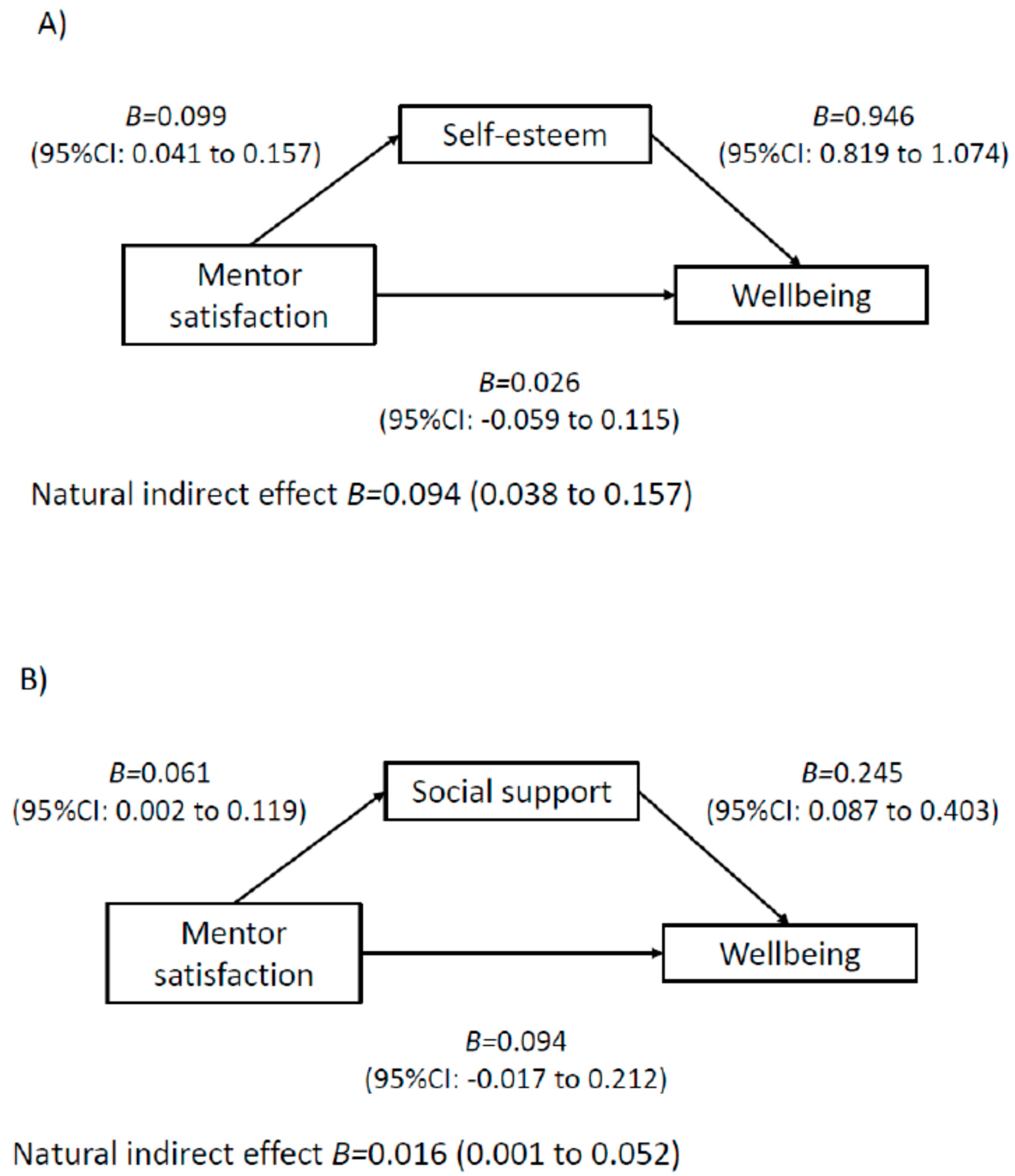

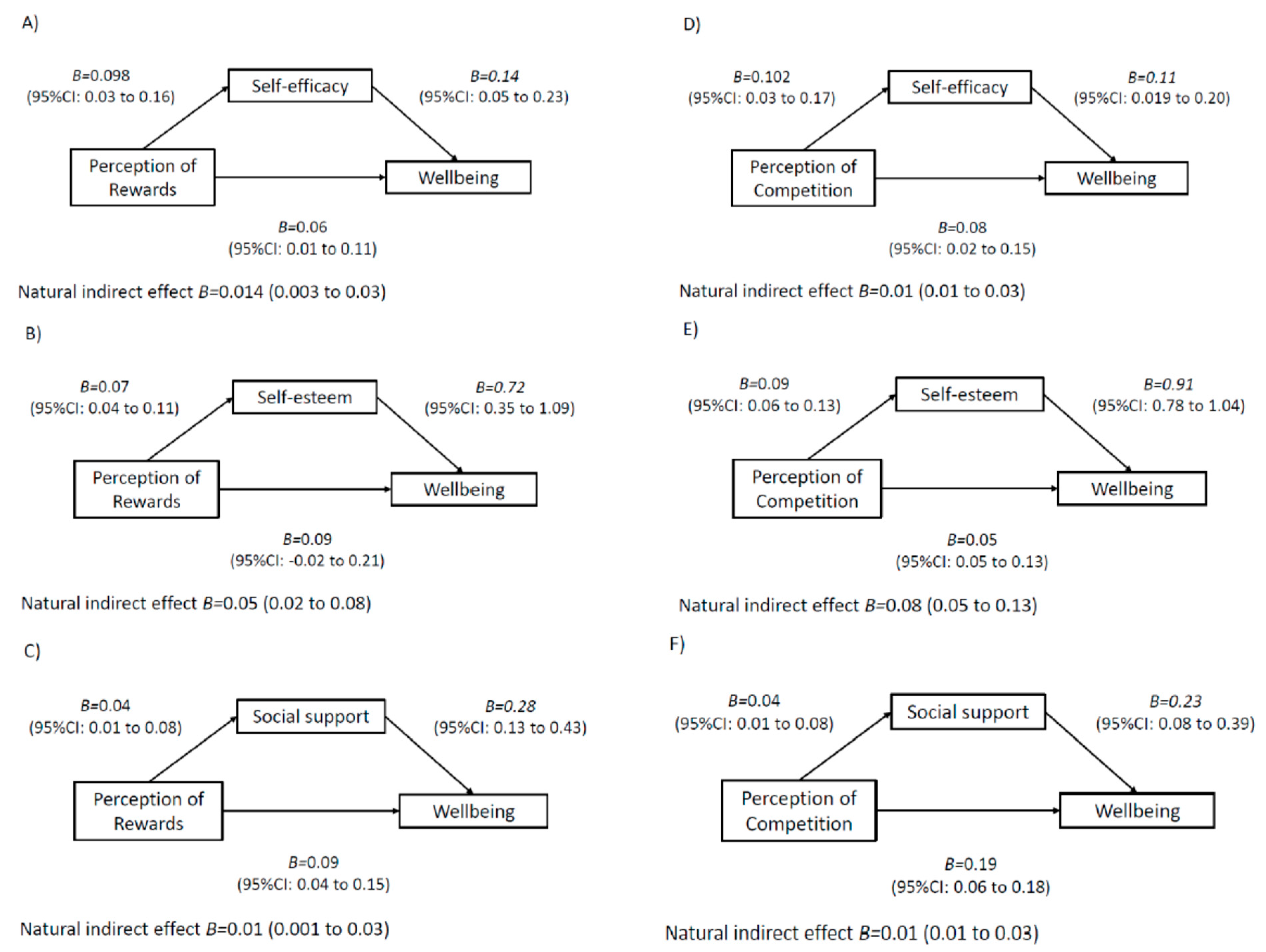

3. Results

4. Discussion

Summary in Relation to Participatory Co-Design Approach

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gunnell, K.E.; Flament, M.F.; Buchholz, A.; Henderson, K.A.; Obeid, N.; Schubert, N.; Goldfield, G.S. Examining the bidirectional relationship between physical activity, screen time, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over time during adolescence. Prev. Med. 2016, 88, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Lawson, K.D.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Finkelstein, E.A.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; van Mechelen, W.; Pratt, M.; Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive. The economic burden of physical inactivity: A global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2016, 388, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.; Riley, L.; Bull, F. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Department of Health and Social Care. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Report: Physical Activity Guidelines. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/physical-activity-guidelines (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- World Health Organization. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.A.; Parkinson, K.N.; Adamson, A.J.; Pearce, M.S.; Reilly, J.K.; Hughes, A.R.; Janssen, X.; Basterfield, L.; Reilly, J.J. Timing of the decline in physical activity in childhood and adolescence: Gateshead Millennium Cohort Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, K.; Winpenny, E.; Love, R.; Brown, H.E.; White, M.; Sluijs, E.V. Change in physical activity from adolescence to early adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, D.; Kidger, J.; Elvidge, H. Adolescent mental health in crisis. BMJ Publ. Group 2018, 361, k2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Angermeyer, M.; Anthony, J.C.; De Graaf, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Gasquet, I.; De Girolamo, G.; Gluzman, S.; Gureje, O.; Haro, J.M. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007, 6, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Patalay, P.; Gage, S.H. Changes in millennial adolescent mental health and health-related behaviours over 10 years: A population cohort comparison study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1650–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Adolescents: Health Risks and Solutions; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen, H.-C.; Metzke, C.W. Risk, compensatory, vulnerability, and protective factors influencing mental health in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2001, 30, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, C.; Díaz-Caneja, C.M.; McGorry, P.D.; Rapoport, J.; Sommer, I.E.; Vorstman, J.A.; McDaid, D.; Marin, O.; Serrano-Drozdowskyj, E.; Freedman, R. Preventive strategies for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.R.; Puterman, E.; Lubans, D.R. Physical inactivity and mental health in late adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 543–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoare, E.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Skouteris, H.; Millar, L.; Nichols, M.; Allender, S. Systematic review of mental health and well-being outcomes following community-based obesity prevention interventions among adolescents. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubans, D.; Richards, J.; Hillman, C.; Faulkner, G.; Beauchamp, M.; Nilsson, M.; Kelly, P.; Smith, J.; Raine, L.; Biddle, S. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, K.; Schiff, A.; Kesten, J.M.; van Sluijs, E.M. Development of a universal approach to increase physical activity among adolescents: The GoActive intervention. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.E.; Whittle, F.; Jong, S.T.; Croxson, C.; Sharp, S.J.; Wilkinson, P.; Wilson, E.C.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Vignoles, A.; Corder, K. A cluster randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the GoActive intervention to increase physical activity among adolescents aged 13–14 years. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, K.; Sharp, S.; Foubister, C.; Brown, H.; Jong, S.; Wells, E.; Armitage, S.; Croxson, C.; Wilkinson, P.; Wilson, E.; et al. Effectiveness of the GoActive intervention to increase physical activity among adolescents: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, H.; Dai, J. Peer Support and Adolescents’ Physical Activity: The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Enjoyment. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, G.; Junior, J.C. Physical activity and social support in adolescents: Analysis of different types and sources of social support. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 1942–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, S.; Croxson, C.; Guell, C.; Lawlor, E.; Foubister, C.; Brown, H.; Wells, E.; Wilkinson, P.; Vignoles, A.; van Sluijs, E.; et al. Adolescents’ perspectives on a school-based physical activity intervention: A mixed method study. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education and Education and Skills Agency Pupil Premium: Funding and Accountability for Schools. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/pupil-premium-information-for-schools-and-alternative-provision-settings (accessed on 5 September 2019).

- Thompson, C.; Wankel, L. The effect of perceived activity choice upon frequency of exercise behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.; Deci, E. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.K.; Kitzman-Ulrich, H.; Williams, J.E.; Saunders, R.; Griffin, S.; Pate, R.; van Horn, M.L.; Evans, A.; Hutto, B.; Addy, C.L.; et al. An overview of “The Active by Choice Today” (ACT) trial for increasing physical activity. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2008, 29, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, K.; Atkin, A.J.; Ekelund, U.; van Sluijs, E.M. What do adolescents want in order to become more active? BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, S.R.; Rosenfeld, W.D.; Spitalny, K.C.; Zansky, S.M.; Bontempo, A.N. The potential role of an adult mentor in influencing high-risk behaviors in adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yancey, A.K.; Siegel, J.M.; McDaniel, K.L. Role models, ethnic identity, and health-risk behaviors in urban adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey-Rothwell, M.A.; Tobin, K.; Yang, C.; Sun, C.J.; Latkin, C.A. Results of a randomized controlled trial of a peer mentor HIV/STI prevention intervention for women over an 18 month follow-up. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.M.; Hager, E.R.; Le, K.; Anliker, J.; Arteaga, S.S.; Diclemente, C.; Gittelsohn, J.; Magder, L.; Papas, M.; Snitker, S.; et al. Challenge! Health promotion/obesity prevention mentorship model among urban, black adolescents. Pediatrics 2010, 126, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.H. Cross-age peer mentoring approach to impact the health outcomes of children and families. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2011, 16, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginis, K.A.; Nigg, C.R.; Smith, A.L. Peer-delivered physical activity interventions: An overlooked opportunity for physical activity promotion. Transl. Behav. Med. 2013, 3, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tate, D.; Larose, J.; Espeland, M.; Wing, R. Study of Novel Approaches to Prevention (SNAP) of Weight Gain in Young Adults: Rationale, Design and Development of Interventions. In Proceedings of the ISBNPA Annul Meeting; ISBNPA: Austin, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hendy, H.M.; Williams, K.E.; Camise, T.S. Kid’s Choice Program improves weight management behaviors and weight status in school children. Appetite 2011, 56, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beets, M.W.; Okely, A.; Weaver, R.G.; Webster, C.; Lubans, D.; Brusseau, T.; Carson, R.; Cliff, D.P. The theory of expanded, extended, and enhanced opportunities for youth physical activity promotion. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.; Westgate, K.; Wareham, N.J.; Brage, S. Estimation of Physical Activity Energy Expenditure during Free-Living from Wrist Accelerometry in UK Adults. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form; The University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, S.; Linley, P.A.; Harwood, J.; Lewis, C.A.; McCollam, P. Rapid assessment of well-being: The Short Depression-Happiness Scale (SDHS). Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2004, 77, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P.; Olsen, L.R.; Kjoller, M.; Rasmussen, N.K. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO-Five well-being scale. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2003, 12, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, F.; Stewart-Brown, S.; Parkinson, J. Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) User Guide; NHS Health Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2015; Available online: http://www.mentalhealthpromotion.net/resources/user-guide.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Ommundsen, Y.; Page, A.; Po-Wen, K.; Cooper, A.R. Cross-cultural, age and gender validation of a computerised questionnaire measuring personal, social and environmental associations with children’s physical activity: The European Youth Heart Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, R.; Pate, R.; Felton, G.; Dowda, M.; Weinrich, M.; Ward, D.; Parsons, M.; Baranowski, T. Development of questionnaires to measure psychosocial influences on children’s physical activity. Prev. Med. 1997, 26, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, T.W. Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer, I.M.; Herbert, J.; Tamplin, A.; Secher, S.M.; Pearson, J. Short-term outcome of major depression: II. Life events, family dysfunction, and friendship difficulties as predictors of persistent disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Conceiving the Self; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, C.; Molcho, M.; Boyce, W.; Holstein, B.; Torsheim, T.; Richter, M. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: The development of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) family affluence scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, T.J.; Bellizzi, M.C.; Flegal, K.M.; Dietz, W.H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ 2000, 320, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeri, L.; Vanderweele, T.J. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: Theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Ding, P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- StataCorp LLC. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jerstad, S.J.; Boutelle, K.N.; Ness, K.K.; Stice, E. Prospective Reciprocal Relations Between Physical Activity and Depression in Female Adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kekäläinen, T.; Freund, A.; Sipilä, S.; Kokko, K. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations between Leisure Time Physical Activity, Mental Well-Being and Subjective Health in Middle Adulthood. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M.A.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Brunner, E.J.; Kaffashian, S.; Shipley, M.J.; Kivimaki, M.; Nabi, H. Bidirectional association between physical activity and symptoms of anxiety and depression: The Whitehall II study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 27, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neissaar, I.; Raudsepp, L. Changes in Physical Activity, Self-Efficacy and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescent Girls. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2011, 23, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Ciaccioni, S.; Thomas, G.; Vergeer, I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianca, D. Performance of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) as a Screening Tool for Depression in UK and Italy. 2012, pp. 48–52. Available online: www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/research/platform/wemwbs/development/papers/donatella_bianco-thesis (accessed on 20 December 2016).

- Stevens, M.; Rees, T.; Coffee, P.; Steffens, N.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Polman, R. A Social Identity Approach to Understanding and Promoting Physical Activity. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorely, T.; Harrington, D.M.; Bodicoat, D.H.; Dayies, M.J.; Khunti, K.; Sherar, L.B.; Tudor-Edwards, R.; Yates, T.; Edwardson, C.L. Process evaluation of the school-based Girls Active programme. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, R.A.; Rehman, L.; Kirk, S.F.L. Understanding gender norms, nutrition, and physical activity in adolescent girls: A scoping review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J. Girls’ active identities: Navigating othering discourses of femininity, bodies and physical education. Gend. Educ. 2015, 27, 666–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, L.; Pender, N.; Kazanis, M. Barriers to Physical Activity Perceived by Adolescent Girls. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2003, 48, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantanista, A.; Osinski, W.; Borowiec, J.; Tomczak, M.; Krol-Zielinska, M. Body image, BMI, and physical activity in girls and boys aged 14–16 years. Body Image 2015, 15, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyremyhr, A.; Diaz, E.; Meland, E. How Adolescent Subjective Health and Satisfaction with Weight and Body Shape Are Related to Participation in Sports. J. Environ. Public Health 2014, 2014, 851932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shochet, I.M.; Dadds, M.R.; Holland, D.; Whitefield, K.; Harnett, P.H.; Osgarby, S.M. The efficacy of a universal school-based program to prevent adolescent depression. J. Clin. Child. Psychol. 2001, 30, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, G.; Lee, J.; Williams, O. Understanding the reproduction of health inequalities: Physical activity, social class and Bourdieu’s habitus. Sport Educ. Soc. 2019, 24, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, R.; Davis, L.; McNeill, J.; Sebire, S.J.; Haase, A.; Powell, J.; Cooper, A.R. Adolescent girls’ and parents’ views on recruiting and retaining girls into an after-school dance intervention: Implications for extra-curricular physical activity provision. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, G.V.; Nettle, D. The behavioural constellation of deprivation: Causes and consequences. Behav. Brain Sci. 2017, 40, e314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, D.M. Individual differences in the neurophysiology of reward and the obesity epidemic. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, S44–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockburn, C.; Clarke, G. “Everybody’s looking at you!”: Girls negotiating the “femininity deficit” they incur in physical education. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2002, 25, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D.M.; Davies, M.J.; Bodicoat, D.H.; Charles, J.M.; Chudasama, Y.V.; Gorely, T.; Khunti, K.; Plekhanova, T.; Rowlands, A.V.; Sherar, L.B.; et al. Effectiveness of the ‘Girls Active’ school-based physical activity programme: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebire, S.; Edwards, M.; Campbell, R.; Jago, R.; Kipping, R.; Banfield, K.; Kadir, B.; Garfield, K.; Lyons, R.; Blair, P.; et al. Update to a protocol for a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of a peer-led school-based intervention to increase the physical activity of adolescent girls (PLAN-A). Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, K.; Brown, H.E.; Schiff, A.; van Sluijs, E.M. Feasibility study and pilot cluster-randomised controlled trial of the GoActive intervention aiming to promote physical activity among adolescents: Outcomes and lessons learnt. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, A.; Jacka, F.N.; Quirk, S.E.; Cocker, F.; Taylor, C.B.; Oldenburg, B.; Berk, M. A shared framework for the common mental disorders and Non-Communicable Disease: Key considerations for disease prevention and control. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education and Education and Skills Agency. Pupil Premium: Allocations and Conditions of Grant 2018 to 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pupil-premium-conditions-of-grant-2018-to-2019 (accessed on 23 July 2019).

- Department for Education and Education and Skills Agency. Ethnicity Facts and Figures. Population of England and Wales. 2019. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest (accessed on 23 July 2019).

- Borde, R.; Smith, J.J.; Sutherland, R.; Nathan, N.; Lubans, D.R. Methodological considerations and impact of school-based interventions on objectively measured physical activity in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, E.K.; Straker, L.M. Rates of attrition, non-compliance and missingness in randomized controlled trials of child physical activity interventions using accelerometers: A brief methodological review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Participatory Perspective Summary [20] | Component | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Adolescents identified that providing choice was important for Year 9 to be interested physical activity with the limited choice of school sports available considered to be a barrier to participation. | Each tutor group chooses two different activities weekly. | Adolescents given an activity choice have better programme attendance [27]. Choice may improve intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy and self-esteem, important for long-term activity maintenance [28,29]. |

| Novelty | The small number of school sports available was a barrier to interest in physical activity and adolescents suggested introducing new types of activities. New activities were stated as important for reducing barriers regarding confidence and lack of skill in common sports as students would begin a new sport with equal ability. | There are 20 activities available, designed to utilise little or no equipment. Intervention materials are available on the study website, which include “quick-cards” (overviews of chosen activities). | Introducing adolescents to new activities is important; those given the opportunity to try new activities are more likely to want to do more [30]. |

| Mentorship | Using older mentors or role models was suggested as more appealing than an intervention delivered by researchers or teachers. Participants suggested that these mentors should be slightly older but not too far from the participants’ age. | Older adolescents in the school (mentors) are paired with each Year 9 class and are responsible for encouraging their class to participate in new activities. Mentors are helped by Year 9 in-class leaders who change weekly. | Peers are crucial for adolescents to attain the best health behaviours in the transition to adulthood [31]. Cross-age mentorship can successfully improve adolescent health behaviours e.g., substance use [32,33], sexual health [34] and nutrition [35] but is understudied in physical activity research [36], particularly in young people [37]. |

| Competition | Competition between tutor groups was suggested to promote participation among a whole school year group and to appeal to those students who would not normally get involved in physical activity. To encourage confidence, participants suggested private individual competition as well as class level competition. They suggested that the former should be kept private so as not to demotivate participants with lower scores. Teachers suggested that competition between tutor groups was an additional way to motivate teachers. | Students gain points every time they do an activity; there is no time limit, students just have to try an activity to get points. Individual points are kept private with class level totals announced to encourage inter-class competition. Students can enter their points on the GoActive website with individual passwords and login details. | Competitions improve engagement and retention in health promotion [38]. |

| Rewards | Receiving rewards for certain levels of participation rather than performance were also suggested as motivating. This was thought to appeal to the competitive nature of students without emphasis on physical activity ability which may not appeal to less active participants. | Students gain small individual prizes for reaching certain points levels with everyone gaining a certain amount of points being entered into a prize draw for a bike. | Reward-based interventions appear effective in improving weight management behaviours in children [39]. |

| Flexibility | There was no clear consensus about when was the best time for physical activity promotion with a range of times suggested, perhaps highlighting the need for flexibility within physical activity promotion. There was a lack of agreement regarding timing and location of activity, however, being able to participate with friends was considered important. Preferences for locations of activity also varied and highlighted the need for flexibility and choices that are sensitive to self-conscious adolescents. | During the feasibility and pilot work, one tutor time weekly has been used to do an activity and participants are also encouraged to do activities at other times, especially out of school. | A range of co-participants, timing and locations for activity are preferred by Year 9 adolescents with preferences differing on an individual level [30]. |

| Activity Sessions | Teachers stated that time was an important barrier to teacher enthusiasm in physical activity interventions. Using tutor time (registration/roll call) physical activity promotion was suggested by teachers. Tutor time usually occurs first thing in the morning and after lunch at British schools when students attend a short class; their form tutor marks attendance and gives out school notices and reminders. Teachers could choose which tutor time(s) were used for running GoActive activities. | Each class was encouraged to use at least one tutor time weekly to participate in activities as a class together. In addition to during tutor time in the classroom, students were also encouraged to do activities at other times in and out of school. Some of the activities were group activities and some were individual. The full list of available activities is available as Supplementary Material. | Providing a new occasion to be active by replacing sedentary time for physical activity has been suggested to lead to successful physical activity promotion [40]. |

| Boys (n = 360) | Girls (n = 311) | P Value for Sex Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Characteristics | |||

| Baseline age (years) | 13.23 (0.42) | 13.24 (0.43) | 0.966 |

| Body mass index z-score | 0.19 (1.25) | 0.38 (1.15) | 0.077 |

| Language (only English), % | 91.64 | 93.06 | 0.490 |

| Ethnicity (white), % | 84.89 | 87.50 | 0.327 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Moderate-to vigorous physical activity change (min/day) | −1.98 (23.40) | −1.55 (17.04) | 0.901 |

| Wellbeing change (score) | −0.03 (0.79) | −0.11 (0.72) | 0.146 |

| Exposures | |||

| Perceived teacher support (score) | 2.47 (0.93) | 2.58 (0.91) | 0.113 |

| Perceived mentor support (score) | 2.61 (0.83) | 2.80 (0.77) | 0.002 |

| Web-based points entered (% versus not entered) | 52.73 | 48.89 | 0.321 |

| Perceived peer-leaders support (score) | 0.47 (0.50) | 0.36 (0.48) | 0.006 |

| Rewards | 3.53 (1.17) | 3.76 (1.35) | 0.024 |

| Competition | 3.40 (1.07) | 3.42 (1.25) | 0.745 |

| Class sessions | 3.42 (1.16) | 3.42 (1.24) | 0.462 |

| Potential Mediators | |||

| Self-efficacy change (score) | −0.09 (0.91) | −0.10 (0.87) | 0.955 |

| Self-esteem change (score) | −0.02 (0.50) | −0.06 (0.45) | 0.108 |

| Social support change (score) | −0.11 (0.55) | −0.12 (0.46) | 0.629 |

| Group cohesion in-degree | −0.16 (1.37) | −0.28 (1.30) | 0.159 |

| Group cohesion out-degree | −0.05 (1.44) | −0.03 (1.24) | 0.883 |

| Friendship quality change (score) | −0.23 (0.55) | −0.21 (0.55) | 0.990 |

| Boys | Girls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity | Wellbeing | Physical Activity | Wellbeing | |

| Perception of Intervention Component | ||||

| Teacher support | 2.93 (0.31 to 5.54) | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.16) | −0.50 (−2.41 to 1.43) | 0.06 (−0.02 to 0.14) |

| Mentor support | 1.47 (−1.51 to 4.45) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.23) | 0.31 (−1.87 to 2.50) | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.20) |

| Class sessions | 1.83 (−0.31, 3.96) | 0.10 (0.03, 0.18) | 0.20 (−1.18, 1.57) | 0.04 (−0.02, 0.05) |

| Peer-leadership | −4.42 (−9.25 to 0.41) | 0.11 (−0.04 to 0.25) | −0.91 (−4.56 to 2.74) | −0.09 (−0.23 to 0.06) |

| Rewards | 2.53 (0.35 to 4.71) | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.14) | 0.35 (−0.97 to 1.67) | 0.10 (0.05 to 0.15) |

| Competition | 1.26 (−1.16 to 3.67) | 0.06 (−0.02 to 0.14) | 0.53 (−0.87 to 1.92) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.18) |

| Online Intervention Component | ||||

| Web-based points | −0.04 (−4.79 to 4.71) | 0.06 (−0.09 to 0.20) | −1.74 (−5.15 to 1.67) | 0.06 (−0.07 to 0.19) |

| Potential Mediators | ||||

| Self-efficacy | −1.10 (−3.94 to 1.75) | 0.08 (−0.01 to 0.16) | 1.75 (−0.32 to 3.82) | 0.20 (0.12 to 0.28) |

| Self-esteem | 4.19 (−1.25 to 9.63) | 0.66 (0.51 to 0.80 | 1.22 (−2.71 to 5.15) | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.08) |

| Social support | −2.90 (−7.51 to 1.71) | 0.43 (0.29 to 0.56) | 1.25 (−2.47 to 4.98) | 0.28 (0.14 to 0.42) |

| Friendship quality | 4.86 (−0.05 to 9.76) | 0.42 (0.28 to 0.57) | 2.29 (−1.19 to 5.78) | 0.66 (0.53 to 0.78) |

| Group cohesion in-degree | 0.65 (−1.42 to 2.71) | −0.01 (−0.08 to 0.07) | 0.08 (−1.44 to 1.60) | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.06) |

| Group cohesion out-degree | −0.87 (−3.00 to 1.26) | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.12) | −0.38 (−2.08 to 1.33) | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.11) |

| Self-Efficacy | Self-Esteem | Social Support | Friendship Quality | GC In-Degree | GC Out-Degree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||||

| Teacher support | 0.12 (0.01 to 0.22) | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.07) | 0.09 (0.03 to 0.15) | 0.00 (−0.05 to 0.06) | −0.14 (−0.29 to 0.01) | 0.01 (−0.14 to 0.15) |

| Mentor support | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.27) | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.13) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.21) | 0.06 (−0.01 to 0.13) | −0.09 (−0.26 to 0.09) | 0.12 (−0.05 to 0.28) |

| Class sessions | 0.02 (−0.07 to 0.11) | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.10) | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.10) | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.13) | 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.13) | 0.20 (0.08 to 0.31) |

| Peer-leadership | 0.15 (−0.05 to 0.34) | −0.08 (−0.18 to 0.02) | 0.06 (−0.05 to 0.17) | −0.04 (−0.15 to 0.08) | −0.22 (−0.50 to 0.53) | 0.14 (−0.14 to 0.41) |

| Rewards | 0.06 (−0.03 to 0.14) | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.06) | 0.04 (−0.01 to 0.09) | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.09) | −0.07 (−0.21, 0.08) | 0.01 (−0.15, 0.16) |

| Competition | 0.02 (−0.07 to 0.12) | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.10) | 0.04 (−0.01 to 0.08) | −0.14 (−0.29, 0.02) | −0.02 (−0.19, 0.14) |

| Web-based points | 0.11 (−0.09 to 0.31) | −0.03 (−0.13 to 0.07) | 0.06 (−0.05 to 0.17) | −0.04 (−0.15 to 0.07) | 0.25 (−0.02 to 0.52) | 0.32 (0.06 to 0.58) |

| Girls | ||||||

| Teacher support | 0.06 (−0.03 to 0.16) | 0.04 (−0.01 to 0.09) | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.08) | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.11) | −0.16 (−0.02 to −0.29) | −0.05 (−0.17 to 0.06) |

| Mentor support | 0.10 (−0.01 to 0.20) | 0.11 (0.05 to 0.17) | 0.06 (0.01 to 0.12) | −0.01 (−0.08 to 0.06) | −0.21 (−0.04 to −0.37) | −0.01 (−0.16 to 0.14) |

| Class sessions | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.12) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.10) | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.10) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09) | 0.03 (−0.07, 0.13) | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.13) |

| Peer-leadership | 0.04 (−0.14 to 0.22) | −0.01 (−0.10 to 0.09) | 0.00 (−0.10 to 0.10) | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.09) | −0.16 (−0.43 to 0.11) | −0.07 (−0.31 to 0.17) |

| Rewards | 0.10 (0.03 to 0.16) | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.11) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.07) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.08) | −0.07 (−0.17, 0.04) | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.16) |

| Competition | 0.10 (0.03 to 0.17) | 0.10 (0.06 to 0.13) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.08) | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.09) | −0.04 (−0.15, 0.08) | 0.12 (0.01, 0.23) |

| Web-based points | 0.12 (−0.04 to 0.28) | 0.00 (−0.09 to 0.09) | 0.01 (−0.11 to 0.08) | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.12) | −0.06 (−0.30 to 0.19) | 0.01 (−0.21 to 0.23) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corder, K.; Werneck, A.O.; Jong, S.T.; Hoare, E.; Brown, H.E.; Foubister, C.; Wilkinson, P.O.; van Sluijs, E.M. Pathways to Increasing Adolescent Physical Activity and Wellbeing: A Mediation Analysis of Intervention Components Designed Using a Participatory Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020390

Corder K, Werneck AO, Jong ST, Hoare E, Brown HE, Foubister C, Wilkinson PO, van Sluijs EM. Pathways to Increasing Adolescent Physical Activity and Wellbeing: A Mediation Analysis of Intervention Components Designed Using a Participatory Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(2):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020390

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorder, Kirsten, André O. Werneck, Stephanie T. Jong, Erin Hoare, Helen Elizabeth Brown, Campbell Foubister, Paul O. Wilkinson, and Esther MF van Sluijs. 2020. "Pathways to Increasing Adolescent Physical Activity and Wellbeing: A Mediation Analysis of Intervention Components Designed Using a Participatory Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020390

APA StyleCorder, K., Werneck, A. O., Jong, S. T., Hoare, E., Brown, H. E., Foubister, C., Wilkinson, P. O., & van Sluijs, E. M. (2020). Pathways to Increasing Adolescent Physical Activity and Wellbeing: A Mediation Analysis of Intervention Components Designed Using a Participatory Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020390