Perceived Parenting Styles and Adjustment during Emerging Adulthood: A Cross-National Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

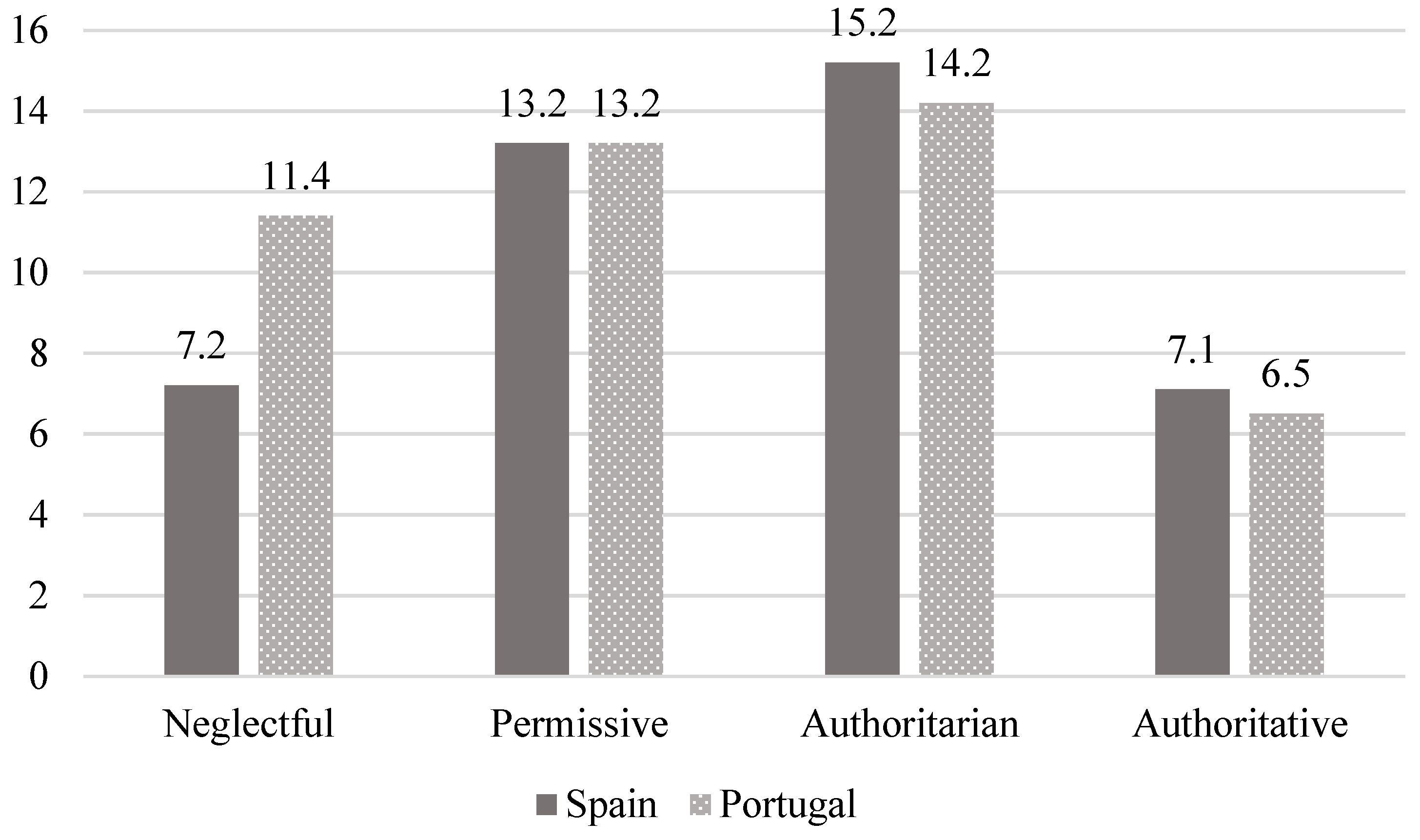

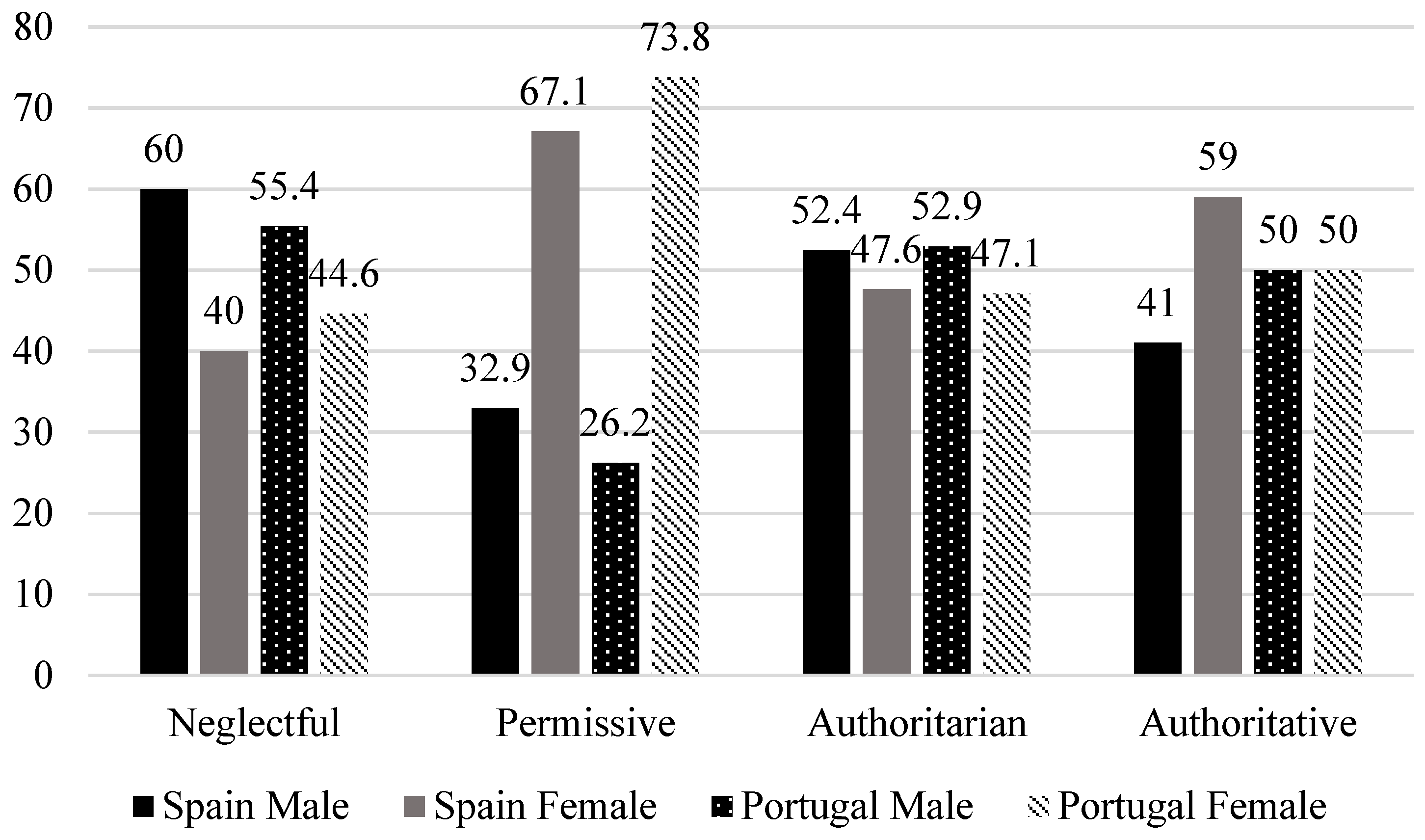

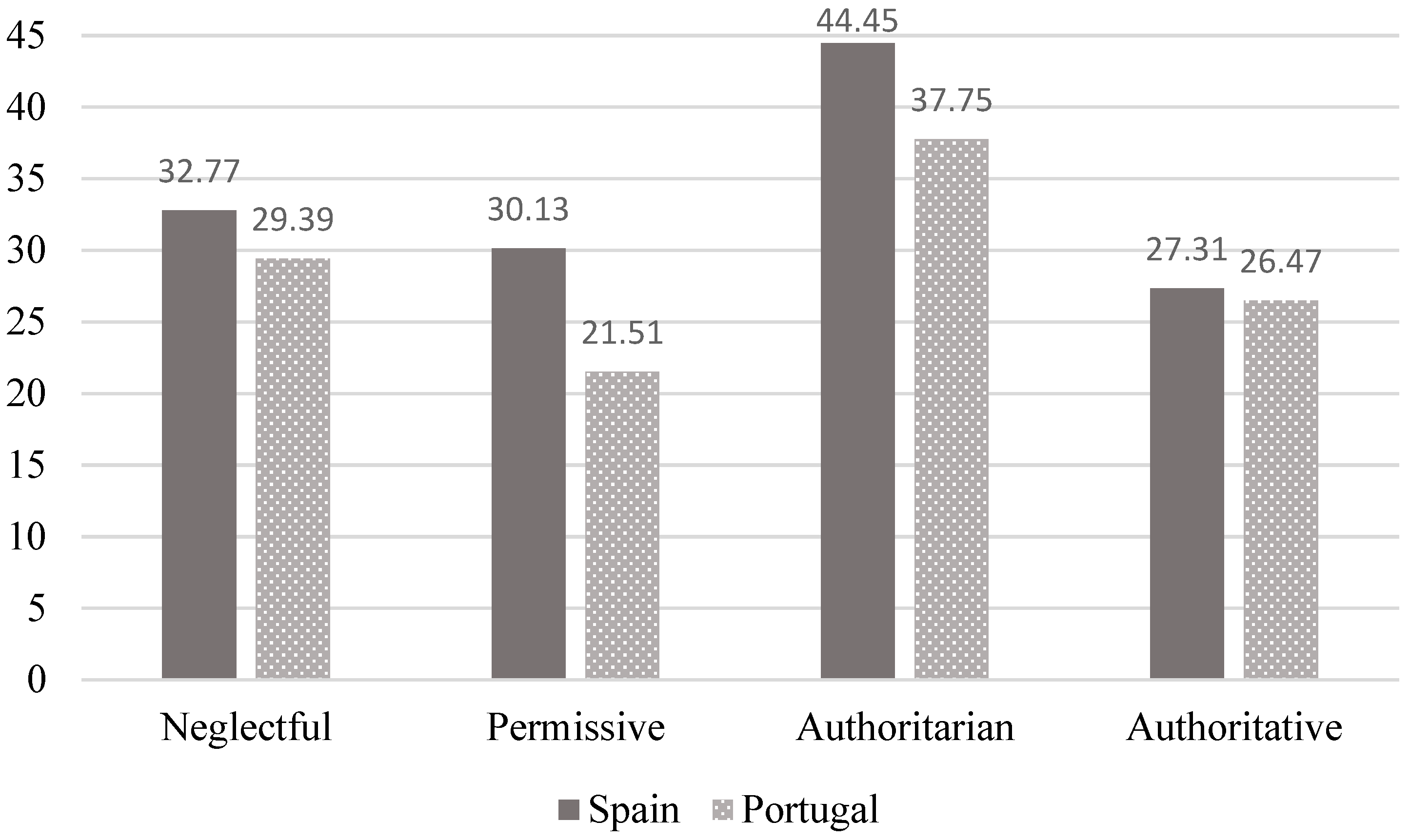

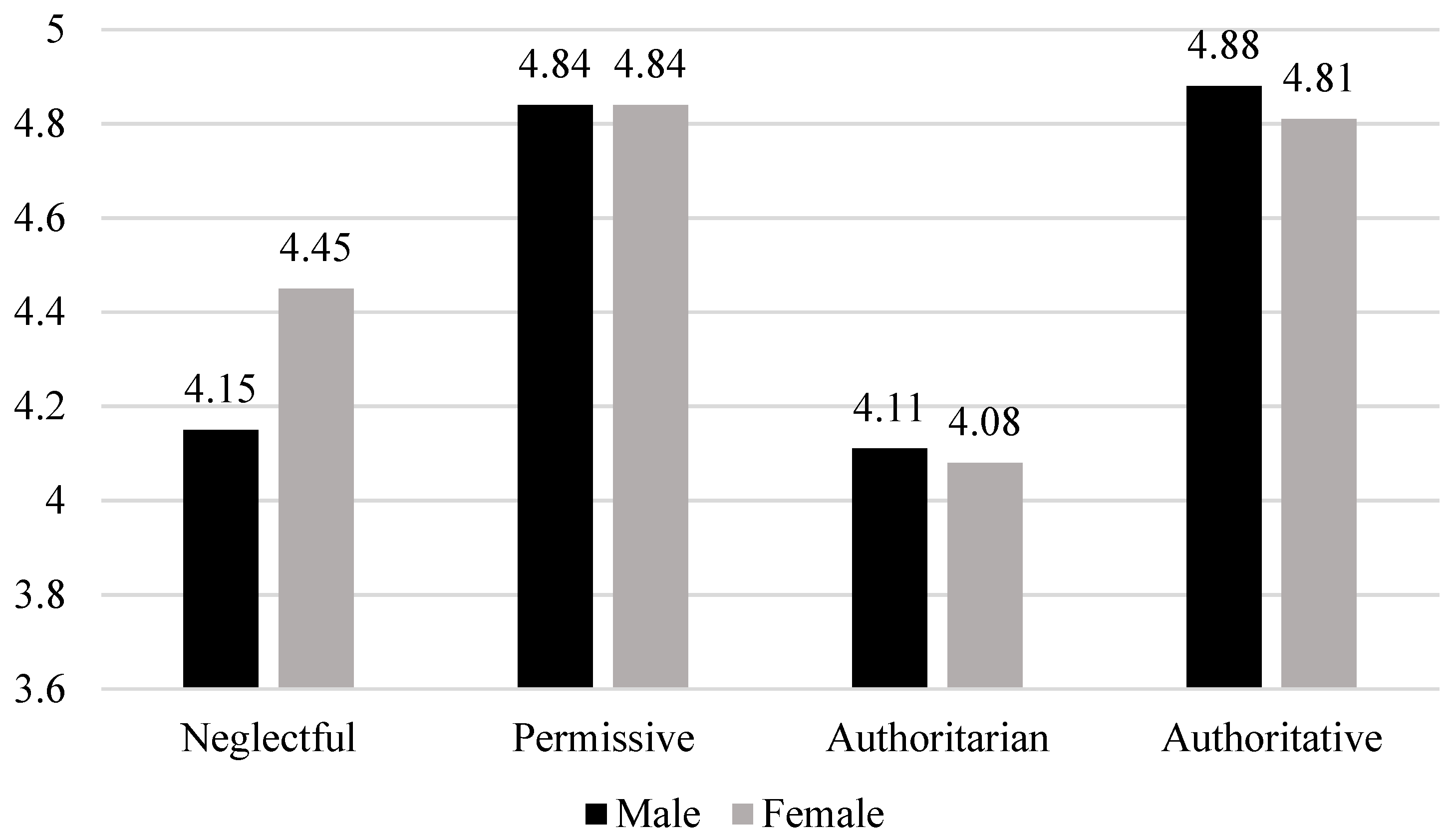

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baumrind, D. Authoritarian vs. authoritative parental control. Adolescence 1968, 3, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development, 4th ed.; Mussen, P.H., Hetherington, E.M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg, G.S.; Bronstein, P. Family factors related to children’s intrinsic/extrinsic motivational orientation and academic performance. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, K.L.; Dornbusch, S.M.; Troyer, L.; Steinberg, L.; Ritter, P.L. Parenting Styles, Adolescents’ Attributions, and Educational Outcomes in Nine Heterogeneous High Schools. Child Dev. 1997, 68, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aunola, K.; Stattin, H.; Nurmi, J.-E. Parenting styles and adolescents’ achievement strategies. J. Adolesc. 2000, 23, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamborn, S.D.; Mounts, N.S.; Steinberg, L.; Dornbusch, S.M. Patterns of Competence and Adjustment among Adolescents from Authoritative, Authoritarian, Indulgent, and Neglectful Families. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L.; Lamborn, S.D.; Dornbusch, S.M.; Darling, N. Impact of Parenting Practices on Adolescent Achievement: Authoritative Parenting, School Involvement, and Encouragement to Succeed. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdek, L.A.; Fine, M.A. Family Acceptance and Family Control as Predictors of Adjustment in Young Adolescents: Linear, Curvilinear, or Interactive Effects? Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L.; Darling, N.E.; Fletcher, A.C.; Brown, B.B.; Dornbusch, S.M. Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment: An ecological journey. In Examining Lives in Context: Perspectives on the Ecology of Human Development; Moen, P., Elder, G.H., Jr., Luscher, K., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 423–466. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M.; Stattin, H.; Ozdemir, M. Perceived parenting style and adolescent adjustment: Revisiting directions of effects and the role of parental knowledge. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1540–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milevsky, A.; Schlechter, M.; Netter, S.; Keehn, D. Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescents: Associations with self-esteem, depression and life-satisfaction. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2007, 16, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziszewska, B.; Richardson, J.L.; Dent, C.W.; Flay, B.R. Parenting style and adolescent depressive symptoms, smoking, and academic achievement: Ethnic, gender, and SES differences. J. Behav. Med. 1996, 19, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, R.K. Extending Research on the Consequences of Parenting Style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calafat, A.; García, F.; Juan, M.; Becoña, E.; Fernández-Hermida, J.R. Which parenting style is more protective against adolescent substance use? Evidence within the European context. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 138, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.; Gracia, E. What is the optimum parental socialisation style in Spain? A study with children and adolescents aged 10–14 years. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2010, 33, 365–384. [Google Scholar]

- Hindin, M.J. Family dynamics, gender differences and educational attainment in Filipino adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2005, 28, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, E.A.; Lefkowitz, E.S. Are mothers’ and fathers’ parenting characteristics associated with emerging adults’ academic engagement? J. Fam. Issues 2017, 38, 1239–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dornbusch, S.M.; Ritter, P.L.; Leiderman, P.H.; Roberts, D.F.; Fraleigh, M.J. The Relation of Parenting Style to Adolescent School Performance. Child Dev. 1987, 58, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L.; Dornbusch, S.M.; Brown, B.B. Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement: An ecological perspective. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Kauser, R. Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2018, 24, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkhabi, N. Applicability of Baumrind’s parent typology to collective cultures: Analysis of cultural explanations of parent socialization effects. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005, 29, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, S.; Super, C.M. Parental Ethnotheories in Action. In Parental Belief Systems: The Psychological Consequences of Children, 2nd ed.; Sigel, I.E., McGillicuddy-DeLisi, A.V., Goodnow, J.J., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992; Volume 2, pp. 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, C.; Brown, K.R. Parenting and Emerging Adult Internalizing Problems: Regional Differences Suggest Southern Parenting Factor. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 3156–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J.; Jensen, A.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. The Oxford Handbook of Emerging Adulthood; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K.L.; Yahirun, J.J. Emerging adulthood in the context of family. In The Oxford Handbook of Emerging Adulthood; Arnett, J.J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.Y.S.; Goldstein, S.E. Loneliness, stress, and social support in young adulthood: Does the source of support matter? J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alt, D. Using structural equation modeling and multidimensional scaling to assess female college students’ academic adjustment as a function of perceived parenting styles. Curr. Psychol. 2016, 35, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.J.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Yu, J. Asian American and European American emerging adults’ perceived parenting styles and self-regulation ability. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2018, 9, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, K.M.; Thomas, D.M. Parenting Styles and Adjustment Outcomes among College Students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2014, 55, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, R.S.; Mendelson, T.; Surkan, P.J.; Bass, J.K.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Hindin, M.J. Parenting styles and emerging adult depressive symptoms in Cebu, the Philippines. Transcult. Psychiatry 2018, 55, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, J.; Blinn-Pike, L.; Worthy, S.L. How is gambling related to perceived parenting style and/or family environment for college students? J. Behav. Addict. 2012, 2, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, C.; Brown, K.; Malkin, M.L. Parenting style, discipline, and parental psychopathology: Gender dyadic interactions in emerging adults. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patock-Peckham, J.A.; Morgan-Lopez, A.A. The gender specific mediational pathways between parenting styles, neuroticism, pathological reasons for drinking, and alcohol-related problems in emerging adulthood. Addict. Behav. 2009, 34, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrade, G.; Ho, R. Differential parenting styles for fathers and mothers. Aust. J. Psychol. 2001, 53, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, C.; Renk, K. Differential parenting between mothers and fathers: Implications for late adolescents. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 806–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Someya, T.; Uehara, T.; Kadowaki, M.; Tang, S.W.; Takahashi, S. Effects of gender difference and birth order on perceived parenting styles, measured by the EMBU scale, in Japanese two-sibling subjects. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000, 54, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, J.; Hendry, L.; Glendinning, A. Models of parenting: Implications for adolescent well-being within different types of family contexts. J. Adolesc. 1995, 18, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. The Evidence for Generation We and Against Generation Me. Emerg. Adulthood 2013, 1, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo de la Juventud de España. Observatorio de Emancipación. Nota Introductoria. Primer Trimestre de 2016. 2017. Available online: http://www.cje.org/es/publicaciones/novedades/observatorio-emancipacion-primer-semestre-2017/ (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Eurostat. Estimated Average Age of Young People Leaving the Parental Household by Sex. Products Datasets. 2018. Available online: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 14 April 2019).

- OECD. Public Spending on Family Benefits; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, A.M.; Andrade, C.; Matias, M.; Gato, J.; Mendonça, M. Valeurs de jeunes couples à double revenu. Rev. Int. Educ. Fam. 2006, 19, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.E.; Mendonça, M.; Coimbra, S.; Fontaine, A.M. Family support in the transition to adulthood in Portugal—Its effects on identity capital development, uncertainty management and psychological well-being. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacouvou, M. Leaving home: Independence, togetherness and income in Europe. Adv. Life Course Res. 2010, 15, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; López, A.; Segado, S. La Transición de los Jóvenes a la Vida Adulta: Crisis Económica Y Emancipación Tardía; Obra Social La Caixa: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, J. European Welfare regimes and the transition to adulthood: A comparative and longitudinal perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 59, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, M.; Fontaine, A.M. Filial maturity in young adult children: The validity of the Filial Maturity Measure and the role of adult transitions. Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 20, 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Hofstede Insights. Country Comparison. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/portugal.spain/ (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- Grolnick, W.S.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Inner resources for school achievement: Motivational mediators of children’s perceptions of their parents. J. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 83, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, R.J. An Assessment of Perceptions of Parental Autonomy Support and Control: Child and Parent Correlates. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Psychology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M.; Stattin, H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bados, A.; Solanas, A.; Andrés, R. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of depression, anxiety and stress scales (DASS). Psicothema 2005, 17, 679–683. [Google Scholar]

- Apóstolo, J.L.A.; Mendes, A.M.O.C.; Azeredo, Z.A. Adaptation to Portuguese of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS). Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2006, 14, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.; Lovibond, S. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, D.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Blanco, A.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Gallardo, I.; Valle, C.; Van Dierendonck, D. Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBS). Psicothema 2006, 18, 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Novo, R.F.; Duarte-Silva, E.; Peralta, E. O bem-estar psicológico em adultos: Estudo das características psicométricas da versão portuguesa das escalas de C. Ryff. In Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos; Gonçalves, M., Ribeiro, I., Araújo, S., Machado, C., Almeida, L.S., Simões, M., Eds.; APPORT/SHOOECD: Braga, Portugal, 1997; Volume 5, pp. 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D.; Lee, Y.H.; Essex, M.J.; Schmutte, P.S. My children and me: Midlife evaluations of grown children and of self. Psychol. Aging 1994, 9, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Musitu, G.; García, J.F. Consecuencias de la socialización familiar en la cultura española. Psicothema 2004, 16, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- García, F.; Gracia, E. Is always authoritative the optimum parenting style? Evidence from Spanish families. Adolescence 2009, 44, 101–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mendoza, M.C.; Sánchez-Queija, I.; Jiménez, A. The Role of Parents in Emerging Adults’ Psychological Well-Being: A Person-Oriented Approach. Fam. Process 2018, 64, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeus, W.; Iedema, J.; Maassen, G.; Engels, R. Separation-individuation revisited: On the interplay of parent-adolescent relations, identity and emotional adjustment in adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2005, 28, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubman, J.G.; Lerner, R.M. Continuity and discontinuity in the affective experiences of parents and children: Evidence from the New York Longitudinal Study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1994, 64, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, G.M.; Caruthers, A.S.; Dishion, T.J. A Six-Year Predictive Test of Adolescent Family Relationship Quality and Effortful Control Pathways to Emerging Adult Social and Emotional Health. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, E.S. “Things Have Gotten Better” Developmental Changes among Emerging Adults after the Transition to University. J. Adolesc. Res. 2005, 20, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, A.; Oliva, A.; Reina, M.C. Family Relationships from Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood a Longitudinal Study. J. Fam. Issues 2013, 36, 2002–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Nelson, L.J.; Knapp, D.J. “Because I’m still the parent, that’s why!” Parental legitimate authority during emerging adulthood. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2014, 31, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Sierens, E. How Are Parental Psychological Control and Autonomy-Support Related? A Cluster-Analytic Approach. J. Marriage Fam. 2009, 71, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E.; Meeus, W. “Family Comes First!” Relationships with family and friends in Italian emerging adults. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milevsky, A.; Thudium, K.; Guldin, J. The Transitory Nature of Parent, Sibling and Romantic Partner Relationships in Emerging Adulthood; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R.; McLaren, S. The association of avoidance coping style, and perceived mother and father support with anxiety/depression among late adolescents: Applicability of resiliency models. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S.; Ratelle, C.F.; LaRose, S.; Guay, F. Adjustment trajectories in college science programs: Perceptions of qualities of parents’ and college teachers’ relationships. J. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 54, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.; Marí-Klose, P. Youth, family change and welfare arrangements: Is the South still so different? Eur. Soc. 2013, 15, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Geta, P.M. Parenting style in Spanish parents with children aged 6 to 14. Psicothema 2012, 24, 371–376. [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Aliri, J. Parental socialization styles, parents’ educational level, and sexist attitudes in adolescence. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.; García, J.F. Internalization of values and self-esteem among Brazilian teenagers from authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful homes. Adolescence 2008, 43, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, C.; Fisk, J.E.; Craig, L. The effects of perceived parenting style on the propensity for illicit drug use: The importance of parental warmth and control. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008, 27, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaureguizar, J.; Bernaras, E.; Bully, P.; Garaigordobil, M. Perceived parenting and adolescents’ adjustment. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, Á.; Oliva, A. Un análisis longitudinal sobre las dimensiones relevantes del estilo parental durante la adolescencia. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2006, 29, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.; Gracia, E. The indulgent parenting style and developmental outcomes in South European and Latin American countries. In Parenting across Cultures. Childrearing, Motherhood and Fatherhood in Non-Western Cutures: The History of Non-Western Science; Selin, H., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2014; Volume 7, pp. 419–433. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, J. La transición residencial de la juventud europea y el Estado de bienestar: Un estudio comparado desde las políticas de vivienda y empleo. Rev. Serv. Soc. 2015, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, J.C. Depression and the response of others. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1976, 85, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Nelson, L.J. Black hawk down?: Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Son, D.; Nelson, L.J. Profiles of Helicopter Parenting, Parental Warmth, and Psychological Control During Emerging Adulthood. Emerg. Adulthood 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parra, Á.; Sánchez-Queija, I.; García-Mendoza, M.d.C.; Coimbra, S.; Egídio Oliveira, J.; Díez, M. Perceived Parenting Styles and Adjustment during Emerging Adulthood: A Cross-National Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152757

Parra Á, Sánchez-Queija I, García-Mendoza MdC, Coimbra S, Egídio Oliveira J, Díez M. Perceived Parenting Styles and Adjustment during Emerging Adulthood: A Cross-National Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(15):2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152757

Chicago/Turabian StyleParra, Águeda, Inmaculada Sánchez-Queija, María del Carmen García-Mendoza, Susana Coimbra, José Egídio Oliveira, and Marta Díez. 2019. "Perceived Parenting Styles and Adjustment during Emerging Adulthood: A Cross-National Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 15: 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152757

APA StyleParra, Á., Sánchez-Queija, I., García-Mendoza, M. d. C., Coimbra, S., Egídio Oliveira, J., & Díez, M. (2019). Perceived Parenting Styles and Adjustment during Emerging Adulthood: A Cross-National Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152757