Creating an Improved Diatoxanthin Production Line by Knocking Out CpSRP54 in the zep3 Background in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Generation of zep3cpsrp54 Double KO Mutants by CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing of the CpSRP54 Gene in zep3 Mutants

2.2. Physiological Features of the zep3cpsrp54 Double KO Mutants

2.3. Induction of NPQ in zep3cpsrp54 Compared with Single Mutants and WT Using Different Light Intensities

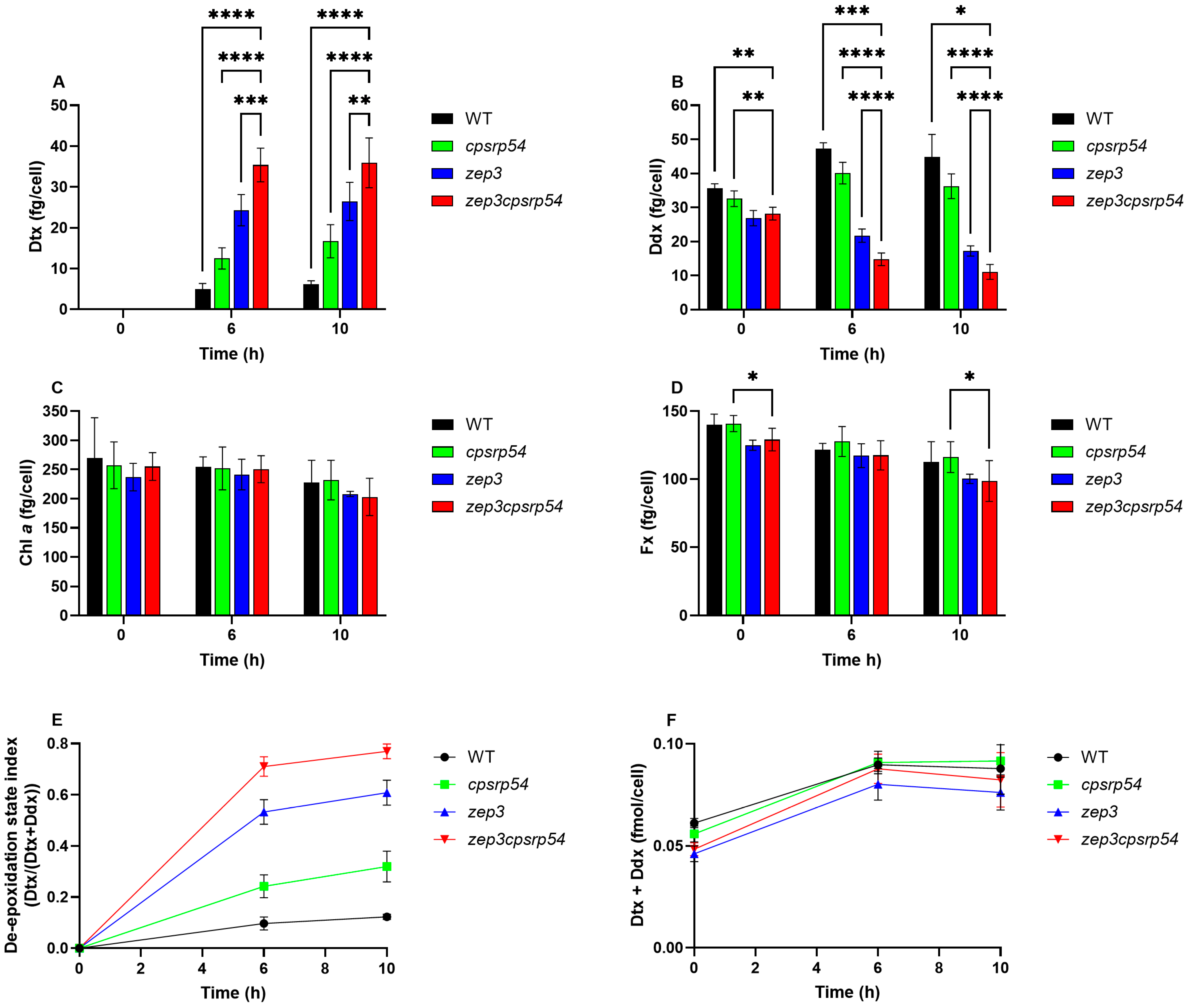

2.4. Dtx Production in zep3cpsrp54 Double KO Compared with Single Mutants and WT as a Result of Prolonged ML Exposure

2.5. Dtx Production in zep3cpsrp54 Double KO Compared with Single Mutants and WT as a Result of Short-Term ML Exposure

2.6. Stability of Dtx in LL Conditions

2.7. Isolation of Non-Transgenic zep3cpsrp54 KO Lines from the Four Independent Mutant Lines

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. P. tricornutum Wild-Type and zep3, cpsrp54 and zep3cpsrp54 Mutant Lines

3.2. Nanopore Sequencing of zep3 Lines

3.3. Light Conditions

3.4. Growth Rates

3.5. Measurements of Photosynthetic Parameters

3.6. Pigment Analysis

3.7. Statistics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ZEP | Zeaxanthin epoxidase |

| CpSRP54 | Chloroplast signal recognition particle 54 |

| Chl | Chlorophyll |

| Fx | Fucoxanthin |

| Dtx | Diatoxanthin |

| Ddx | Diadinoxanthin |

| VDE | Violaxanthin de-epoxidase |

| LHC | Light-harvesting complex |

| KO | Knock out |

| NPQ | Non-photochemical quenching |

| PAM | Protospacer adjacent motifs |

| LL | Low light |

| ML | Medium light |

| HL | High light |

| WT | Wild-type |

| rETRmax | Maximum relative electron transport rate |

| Ek | Light saturation index |

| Alpha | Maximum light utilisation coefficient |

| DES | De-epoxidation state |

| PSII | Photosystem II |

| FCP | Fx Chl a/c-binding protein |

| IVF | In vivo Chl a fluorescence |

| RLC | Rapid light curve |

References

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as Natural Functional Pigments. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmann, G. Diversity and Origin of Carotenoid Biosynthesis: Its History of Coevolution towards Plant Photosynthesis. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Bassi, A. Carotenoids from Microalgae: A Review of Recent Developments. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1396–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domonkos, I.; Kis, M.; Gombos, Z.; Ughy, B. Carotenoids, Versatile Components of Oxygenic Photosynthesis. Prog. Lipid. Res. 2013, 52, 539–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour-Varnami, K.; Mohamadnia, S.; Tavakoli, O.; Faramarzi, M.A. A Review on the Biological Activities of Key Carotenoids: Structures, Sources, Market, Economical Features, and Stability. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Mandić, A.I.; Bantis, F.; Böhm, V.; Borge, G.I.A.; Brnčić, M.; Bysted, A.; Cano, M.P.; Dias, M.G.; Elgersma, A.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on Carotenoids in Foods and Feeds: Status Quo, Applications, Patents, and Research Needs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, A.; Basirnejad, M.; Shahbazi, S.; Bolhassani, A. Carotenoids: Biochemistry, Pharmacology and Treatment. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1290–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathasivam, R.; Ki, J.-S. A Review of the Biological Activities of Microalgal Carotenoids and Their Potential Use in Healthcare and Cosmetic Industries. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowles, J.L.; Erdman, J.W. Carotenoids and Their Role in Cancer Prevention. BBA-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2020, 1865, 158613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, I.; Cadier, E.; Beulens, J.W.J.; van der A, D.L.; Spijkerman, A.M.W.; van der Schouw, Y.T. Dietary Intake of Carotenoids and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis 2015, 25, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.T.; Rahman, M.H.; Shah, M.; Jamiruddin, M.R.; Basak, D.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Bhatia, S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Najda, A.; El-kott, A.F.; et al. Therapeutic Promise of Carotenoids as Antioxidants and Anti-Inflammatory Agents in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tang, R.; Zhou, R.; Qian, Y.; Di, D. The Protective Effect of Serum Carotenoids on Cardiovascular Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study from the General US Adult Population. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1154239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Flora, G.; Sevanan, M.; Sripriya, R.; Chen, W.H.; Park, J.-H.; Rajesh Banu, J.; Kumar, G. Technological Advances in the Production of Carotenoids and Their Applications—A Critical Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 367, 128215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Román, J.; García-Gil, S.; Rodríguez-Luna, A.; Motilva, V.; Talero, E. Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Effects of Microalgal Carotenoids. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, C.; Barredo, J.-L. Carotenoids Production: A Healthy and Profitable Industry. In Microbial Carotenoids; Barreiro, C., Barredo, J.-L., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1852, pp. 45–55. ISBN 978-1-4939-8741-2. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, R.; Vaz, B.; Gronemeyer, H.; de Lera, Á.R. Functions, Therapeutic Applications, and Synthesis of Retinoids and Carotenoids. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.S.; Caetano, P.A.; Jacob-Lopes, E.; Zepka, L.Q.; de Rosso, V.V. Alternative Green Solvents Associated with Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction: A Green Chemistry Approach for the Extraction of Carotenoids and Chlorophylls from Microalgae. Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kultys, E.; Kurek, M.A. Green Extraction of Carotenoids from Fruit and Vegetable Byproducts: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, E.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Optimisation of Fucoxanthin Extraction from Irish Seaweeds by Response Surface Methodology. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneesh, P.A.; Ajeeshkumar, K.K.; Lekshmi, R.G.K.; Anandan, R.; Ravishankar, C.N.; Mathew, S. Bioactivities of Astaxanthin from Natural Sources, Augmenting Its Biomedical Potential: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 125, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amotz, A.; Levy, Y. Bioavailability of a Natural Isomer Mixture Compared with Synthetic All-Trans Beta-Carotene in Human Serum. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 63, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanaida, M.; Mykhailenko, O.; Lysiuk, R.; Hudz, N.; Balwierz, R.; Shulhai, A.; Shapovalova, N.; Shanaida, V.; Bjørklund, G. Carotenoids for Antiaging: Nutraceutical, Pharmaceutical, and Cosmeceutical Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, T.G. Bioactivity and Bioavailability of Carotenoids Applied in Human Health: Technological Advances and Innovation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, R.; Lepetit, B. Biodiversity of NPQ. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 172, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konishi, I.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Maoka, T.; Miyashita, K. Suppressive Effects of Alloxanthin and Diatoxanthin from Halocynthia Roretzi on LPS-Induced Expression of pro-Inflammatory Genes in RAW264.7 Cells. J. Oleo Sci. 2008, 57, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistelli, L.; Sansone, C.; Smerilli, A.; Festa, M.; Noonan, D.M.; Albini, A.; Brunet, C. MMP-9 and IL-1β as Targets for Diatoxanthin and Related Microalgal Pigments: Potential Chemopreventive and Photoprotective Agents. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C.; Pistelli, L.; Brunet, C. The Marine Xanthophyll Diatoxanthin as Ferroptosis Inducer in MDAMB231 Breast Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C.; Pistelli, L.; Calabrone, L.; Del Mondo, A.; Fontana, A.; Festa, M.; Noonan, D.M.; Albini, A.; Brunet, C. The Carotenoid Diatoxanthin Modulates Inflammatory and Angiogenesis Pathways In Vitro in Prostate Cancer Cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C.; Pistelli, L.; Del Mondo, A.; Calabrone, L.; Fontana, A.; Noonan, D.M.; Albini, A.; Brunet, C. The Microalgal Diatoxanthin Inflects the Cytokine Storm in SARS-CoV-2 Stimulated ACE2 Overexpressing Lung Cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Græsholt, C.; Brembu, T.; Volpe, C.; Bartosova, Z.; Serif, M.; Winge, P.; Nymark, M. Zeaxanthin Epoxidase 3 Knockout Mutants of the Model Diatom Phaeodactylum Tricornutum Enable Commercial Production of the Bioactive Carotenoid Diatoxanthin. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Chew, K.W.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, J.W.; Ho, S.-H.; Show, P.L. A Review on Microalgae Cultivation and Harvesting, and Their Biomass Extraction Processing Using Ionic Liquids. Bioengineered 2020, 11, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, M.A.; Paton, A.J.; Bai, Y.; Kassaw, T.; Lohr, M.; Peers, G. Identifying the Gene Responsible for Non-photochemical Quenching Reversal in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant J. 2024, 120, 2113–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nymark, M.; Valle, K.C.; Brembu, T.; Hancke, K.; Winge, P.; Andresen, K.; Johnsen, G.; Bones, A.M. An Integrated Analysis of Molecular Acclimation to High Light in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilertsen, H.C.; Eriksen, G.K.; Bergum, J.-S.; Strømholt, J.; Elvevoll, E.; Eilertsen, K.-E.; Heimstad, E.S.; Giæver, I.H.; Israelsen, L.; Svenning, J.B.; et al. Mass Cultivation of Microalgae: I. Experiences with Vertical Column Airlift Photobioreactors, Diatoms and CO2 Sequestration. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, A. Solar Energy Conversion Efficiencies in Photosynthesis: Minimizing the Chlorophyll Antennae to Maximize Efficiency. Plant Sci. 2009, 177, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.; Vázquez Calderón, F.; Sánchez López, J.; Azevedo, I.C.; Bruhn, A.; Fluch, S.; Garcia Tasende, M.; Ghaderiardakani, F.; Ilmjärv, T.; Laurans, M.; et al. Current Status of the Algae Production Industry in Europe: An Emerging Sector of the Blue Bioeconomy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7, 626389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Jung, Y.-J.; Kwon, O.-N.; Cha, K.H.; Um, B.-H.; Chung, D.; Pan, C.-H. A Potential Commercial Source of Fucoxanthin Extracted from the Microalga Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 166, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.K.; Chen, C.-Y.; Varjani, S.; Chang, J.-S. Producing Fucoxanthin from AlgaeRecent Advances in Cultivation Strategies and Downstream Processing. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrede, A.; Mydland, L.T.; Ahlstrom, O.; Reitan, K.I.; Gislerod, H.R.; Overland, M. Evaluation of Microalgae as Sources of Digestible Nutrients for Monogastric Animals. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2011, 20, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.; Berge, G.M.; Reitan, K.I.; Ruyter, B. Microalga Phaeodactylum Tricornutum in Feed for Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar)—Effect on Nutrient Digestibility, Growth and Utilization of Feed. Aquaculture 2016, 460, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, C.; Allen, A.E.; Badger, J.H.; Grimwood, J.; Jabbari, K.; Kuo, A.; Maheswari, U.; Martens, C.; Maumus, F.; Otillar, R.P.; et al. The Phaeodactylum Genome Reveals the Evolutionary History of Diatom Genomes. Nature 2008, 456, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karas, B.J.; Diner, R.E.; Lefebvre, S.C.; McQuaid, J.; Phillips, A.P.R.; Noddings, C.M.; Brunson, J.K.; Valas, R.E.; Deerinck, T.J.; Jablanovic, J.; et al. Designer Diatom Episomes Delivered by Bacterial Conjugation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nymark, M.; Sharma, A.K.; Sparstad, T.; Bones, A.M.; Winge, P. A CRISPR/Cas9 System Adapted for Gene Editing in Marine Algae. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Nymark, M.; Sparstad, T.; Bones, A.M.; Winge, P. Transgene-Free Genome Editing in Marine Algae by Bacterial Conjugation—Comparison with Biolistic CRISPR/Cas9 Transformation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siaut, M.; Heijde, M.; Mangogna, M.; Montsant, A.; Coesel, S.; Allen, A.; Manfredonia, A.; Falciatore, A.; Bowler, C. Molecular Toolbox for Studying Diatom Biology in Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Gene 2007, 406, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nymark, M.; Hafskjold, M.C.G.; Volpe, C.; Fonseca, D.D.; Sharma, A.; Tsirvouli, E.; Serif, M.; Winge, P.; Finazzi, G.; Bones, A.M. Functional Studies of CpSRP54 in Diatoms Show That the Mechanism of Thylakoid Protein Insertion Differs from That in Plants and Green Algae. Plant J. 2021, 106, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Baek, K.; Kirst, H.; Melis, A.; Jin, E. Loss of CpSRP54 Function Leads to a Truncated Light-Harvesting Antenna Size in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2017, 1858, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziehe, D.; Dunschede, B.; Schunemann, D. Molecular Mechanism of SRP-Dependent Light-Harvesting Protein Transport to the Thylakoid Membrane in Plants. Photosynth. Res. 2018, 138, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giossi, C.E.; Bitnel, D.B.; Wünsch, M.A.; Kroth, P.G.; Lepetit, B. Synergistic Effects of Temperature and Light on Photoprotection in the Model Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blommaert, L.; Chafai, L.; Bailleul, B. The Fine-Tuning of NPQ in Diatoms Relies on the Regulation of Both Xanthophyll Cycle Enzymes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavaud, J.; Rousseau, B.; van Gorkom, H.J.; Etienne, A.L. Influence of the Diadinoxanthin Pool Size on Photoprotection in the Marine Planktonic Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavaud, J.; Rousseau, B.; Etienne, A.L. General Features of Photoprotection by Energy Dissipation in Planktonic Diatoms (Bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol. 2004, 40, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawley, M.W. Effects of Llight Intensity and Temperature Interactions on Growth Characteristics of Phaeodactylum Tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol 1984, 20, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaud, G.M.; Mairet, F.; Sciandra, A.; Bernard, O. Modeling the Temperature Effect on the Specific Growth Rate of Phytoplankton: A Review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol 2017, 16, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, J.; Bao, F. Effects of Chilling on the Structure, Function and Development of Chloroplasts. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, N.; Takahashi, S.; Nishiyama, Y.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Photoinhibition of Photosystem II Under Environmental Stress. BBA Bioenerg. 2007, 1767, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, A.; Goss, R.; Jakob, T.; Wilhelm, C. Investigation of the Quenching Efficiency of Diatoxanthin in Cells of Phaeodactylum Tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae) with Different Pool Sizes of Xanthophyll Cycle Pigments. Phycologia 2007, 46, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepetit, B.; Sturm, S.; Rogato, A.; Gruber, A.; Sachse, M.; Falciatore, A.; Kroth, P.G.; Lavaud, J. High Light Acclimation in the Secondary Plastids Containing Diatom Phaeodactylum Tricornutum Is Triggered by the Redox State of the Plastoquinone Pool. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepetit, B.; Volke, D.; Gilbert, M.; Wilhelm, C.; Goss, R. Evidence for the Existence of One Antenna-Associated, Lipid-Dissolved and Two Protein-Bound Pools of Diadinoxanthin Cycle Pigments in Diatoms. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1905–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, K.C.; Nymark, M.; Aamot, I.; Hancke, K.; Winge, P.; Andresen, K.; Johnsen, G.; Brembu, T.; Bones, A.M. System Responses to Equal Doses of Photosynthetically Usable Radiation of Blue, Green, and Red Light in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, U.; Dietzel, L.; Breitenbach, J.; Büchel, C.; Sandmann, G. Identification of Genes Coding for Functional Zeaxanthin Epoxidases in the Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 192, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, M.K.; Mishra, S.; Bhat, A.; Chib, S.; Kaul, S. Plant Carotenoid Cleavage Oxygenases: Structure–Function Relationships and Role in Development and Metabolism. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2020, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, B. EU Regulation of Gene-Edited Plants—A Reform Proposal. Front. Genome Ed. 2023, 5, 1119442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, E. With a Free Pass, CRISPR-Edited Plants Reach Market in Record Time. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, E. Gene-Edited CRISPR Mushroom Escapes US Regulation. Nature 2016, 532, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götz, L.; Svanidze, M.; Tissier, A.; Brand Duran, A. Consumers’ Willingness to Buy CRISPR Gene-Edited Tomatoes: Evidence from a Choice Experiment Case Study in Germany. Sustainability 2022, 14, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; House, L.A.; Gao, Z. How Do Consumers Respond to Labels for Crispr (Gene-Editing)? Food Policy 2022, 112, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, T.; Araki, M. Consumer Acceptance of Food Crops Developed by Genome Editing. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadich, T.; Escobar-Aguirre, S. Citizens’ Attitudes and Perceptions towards Genetically Modified Food in Chile: Special Emphasis in CRISPR Technology. Austral. J. Vet. Sci. 2022, 54, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, S.S.; Diamond, A.; Wang, H.; Therrien, J.A.; Lant, J.T.; Jazey, T.; Lee, K.; Klassen, Z.; Desgagne-Penix, I.; Karas, B.J.; et al. An Expanded Plasmid-Based Genetic Toolbox Enables Cas9 Genome Editing and Stable Maintenance of Synthetic Pathways in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nymark, M.; Sharma, A.K.; Hafskjold, M.C.; Sparstad, T.; Bones, A.M.; Winge, P. CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Bio-Protoc. 2017, 7, e2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nymark, M.; Finazzi, G.; Volpe, C.; Serif, M.; Fonseca, D.d.M.; Sharma, A.; Sanchez, N.; Sharma, A.K.; Ashcroft, F.; Kissen, R.; et al. Loss of CpFTSY Reduces Photosynthetic Performance and Affects Insertion of PsaC of PSI in Diatoms. Plant Cell Physiol. 2023, 64, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, S.; Walenz, B.P.; Berlin, K.; Miller, J.R.; Bergman, N.H.; Phillippy, A.M. Canu: Scalable and Accurate Long-Read Assembly via Adaptive k-Mer Weighting and Repeat Separation. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, R.R.L. Culture of Phytoplankton for Feeding Marine Invertebrates. In Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals: Proceedings—1st Conference on Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals, Greenport, NY, USA, October 1972; Smith, W.L., Chanley, M.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 29–60. ISBN 978-1-4615-8714-9. [Google Scholar]

- Volpe, C.; Vadstein, O.; Andersen, G.; Andersen, T. Nanocosm: A Well Plate Photobioreactor for Environmental and Biotechnological Studies. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 2027–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, F.; Chauton, M.; Johnsen, G.; Andresen, K.; Olsen, L.M.; Zapata, M. Photoacclimation in Phytoplankton: Implications for Biomass Estimates, Pigment Functionality and Chemotaxonomy. Mar. Biol. 2006, 148, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Nymark, M.; Flo, S.; Sparstad, T.; Bones, A.M.; Winge, P. Simultaneous Knockout of Multiple LHCF Genes Using Single SgRNAs and Engineering of a High-Fidelity Cas9 for Precise Genome Editing in Marine Algae. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1658–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwoba, E.G.; Parlevliet, D.A.; Laird, D.W.; Alameh, K.; Moheimani, N.R. Light Management Technologies for Increasing Algal Photobioreactor Efficiency. Algal Res. 2019, 39, 101433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béchet, Q.; Shilton, A.; Fringer, O.B.; Muñoz, R.; Guieysse, B. Mechanistic Modeling of Broth Temperature in Outdoor Photobioreactors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2197–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Saiki, H. Evaluation of Photobioreactor Heat Balance for Predicting Changes in Culture Medium Temperature Due to Light Irradiation. Biotech. Bioeng. 2001, 74, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georlette, D.; Blaise, V.; Collins, T.; D’Amico, S.; Gratia, E.; Hoyoux, A.; Marx, J.-C.; Sonan, G.; Feller, G.; Gerday, C. Some like It Cold: Biocatalysis at Low Temperatures. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 28, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Volpe, C.; Bartosova, Z.; Kissen, R.; Winge, P.; Nymark, M. Creating an Improved Diatoxanthin Production Line by Knocking Out CpSRP54 in the zep3 Background in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110419

Volpe C, Bartosova Z, Kissen R, Winge P, Nymark M. Creating an Improved Diatoxanthin Production Line by Knocking Out CpSRP54 in the zep3 Background in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(11):419. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110419

Chicago/Turabian StyleVolpe, Charlotte, Zdenka Bartosova, Ralph Kissen, Per Winge, and Marianne Nymark. 2025. "Creating an Improved Diatoxanthin Production Line by Knocking Out CpSRP54 in the zep3 Background in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum" Marine Drugs 23, no. 11: 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110419

APA StyleVolpe, C., Bartosova, Z., Kissen, R., Winge, P., & Nymark, M. (2025). Creating an Improved Diatoxanthin Production Line by Knocking Out CpSRP54 in the zep3 Background in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Marine Drugs, 23(11), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110419