Some Bioactive Natural Products from Diatoms: Structures, Biosyntheses, Biological Roles, and Properties: 2015–2025

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Endometabolites from Diatoms

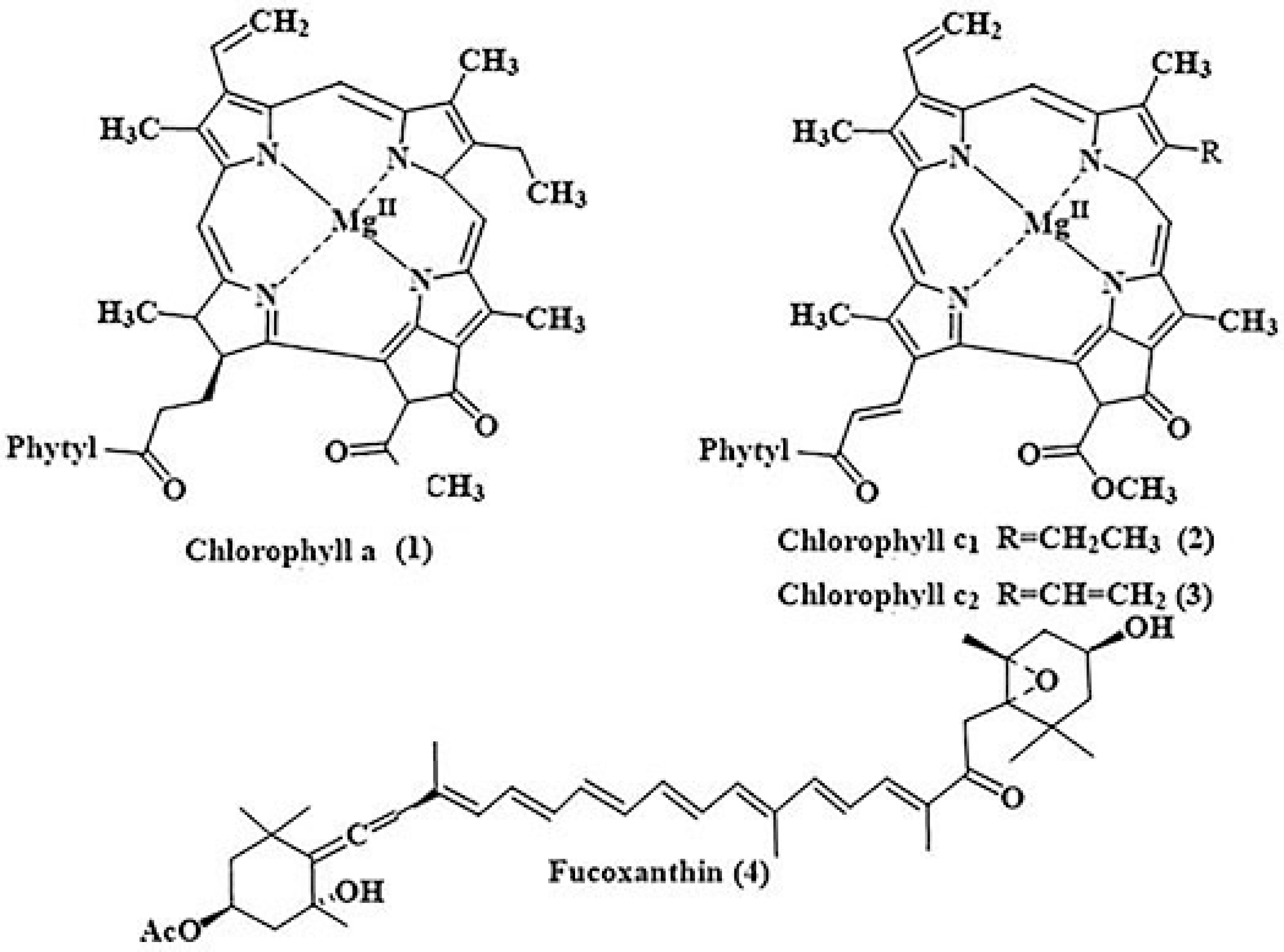

2.1. Pigments

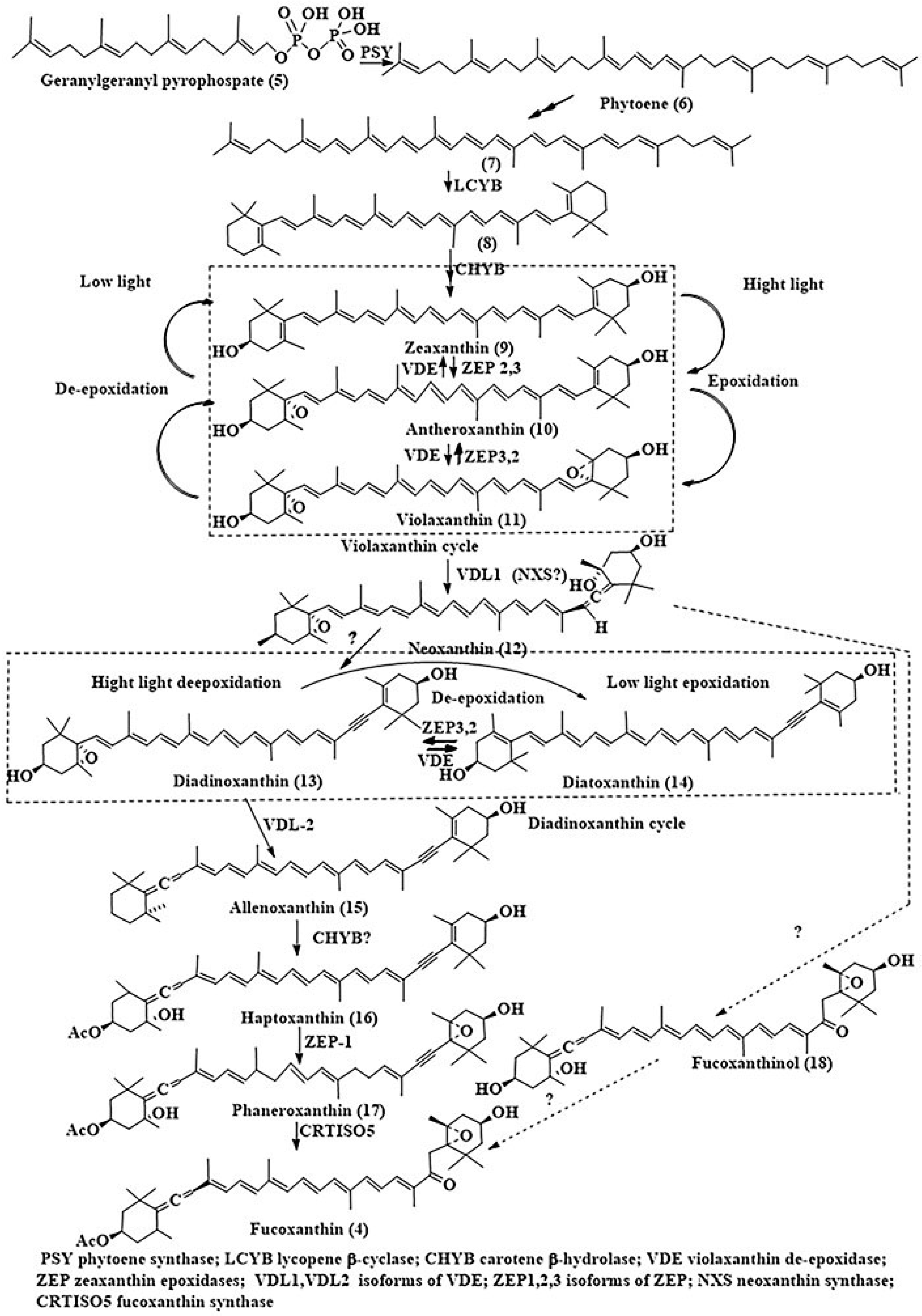

2.1.1. Fucoxanthin (Fcx)

2.1.2. Marennine (Mar)

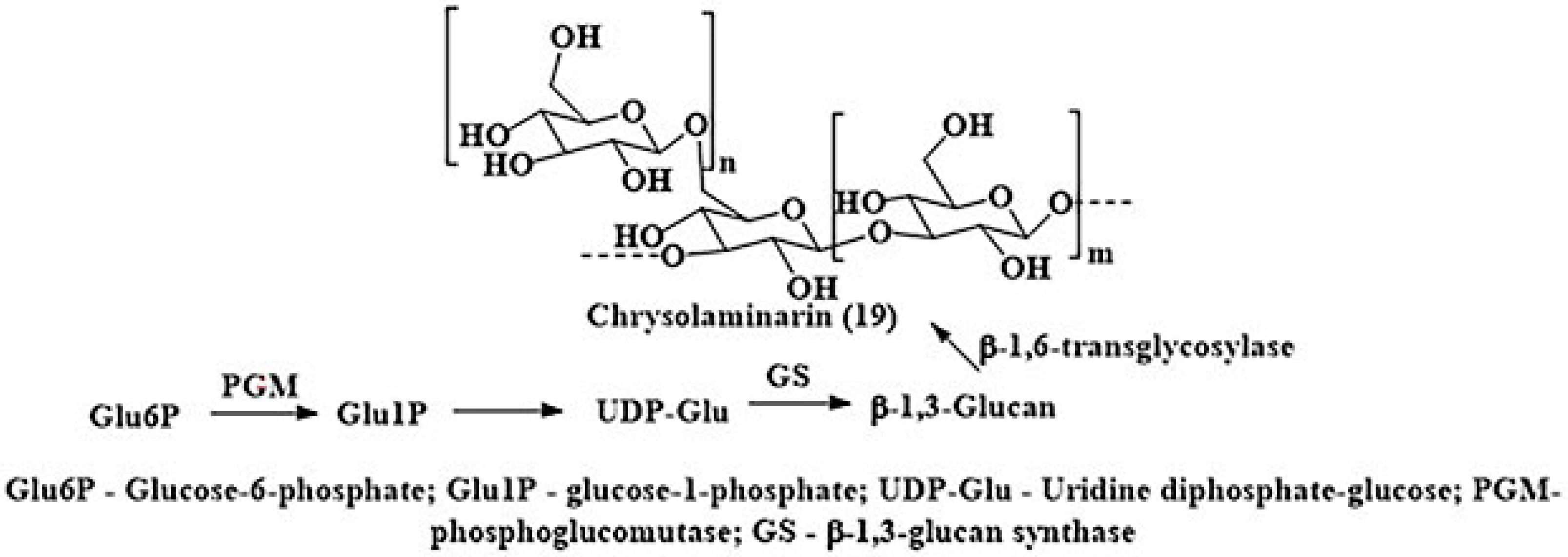

2.2. Chrysolaminarins (Chrls)

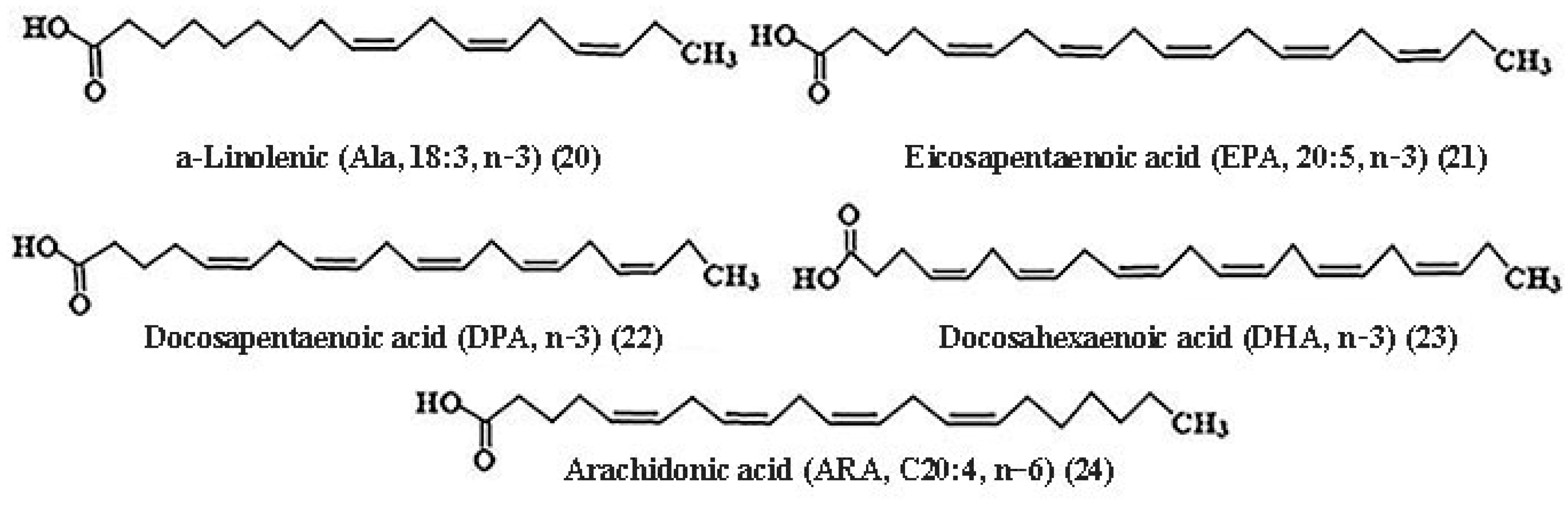

2.3. Lipids

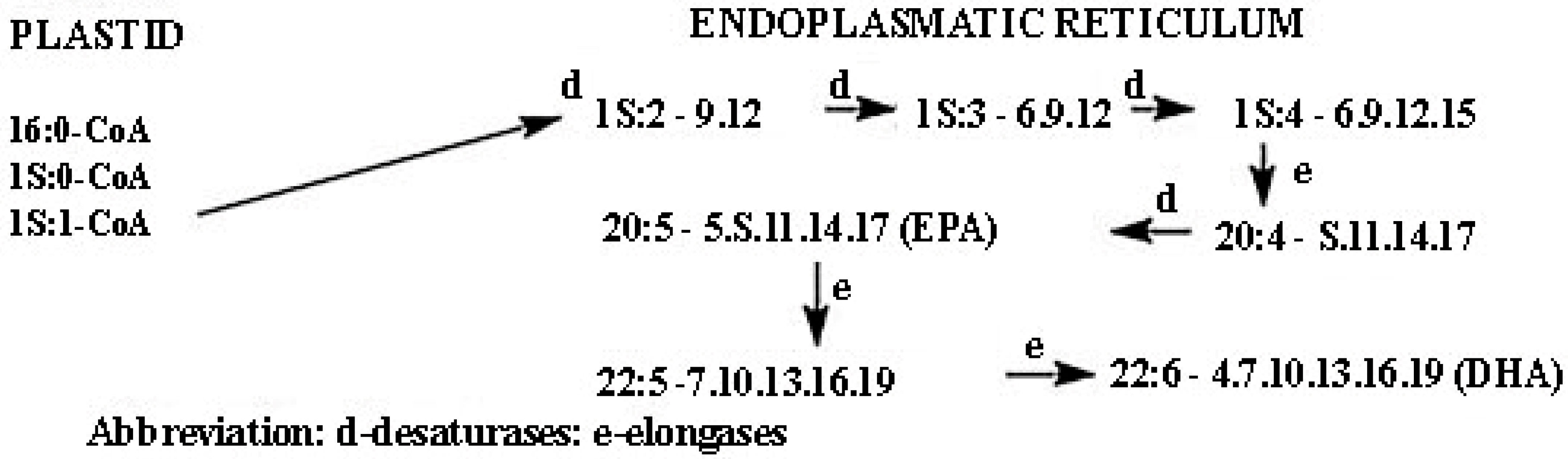

2.3.1. Fatty Acids (FAs)

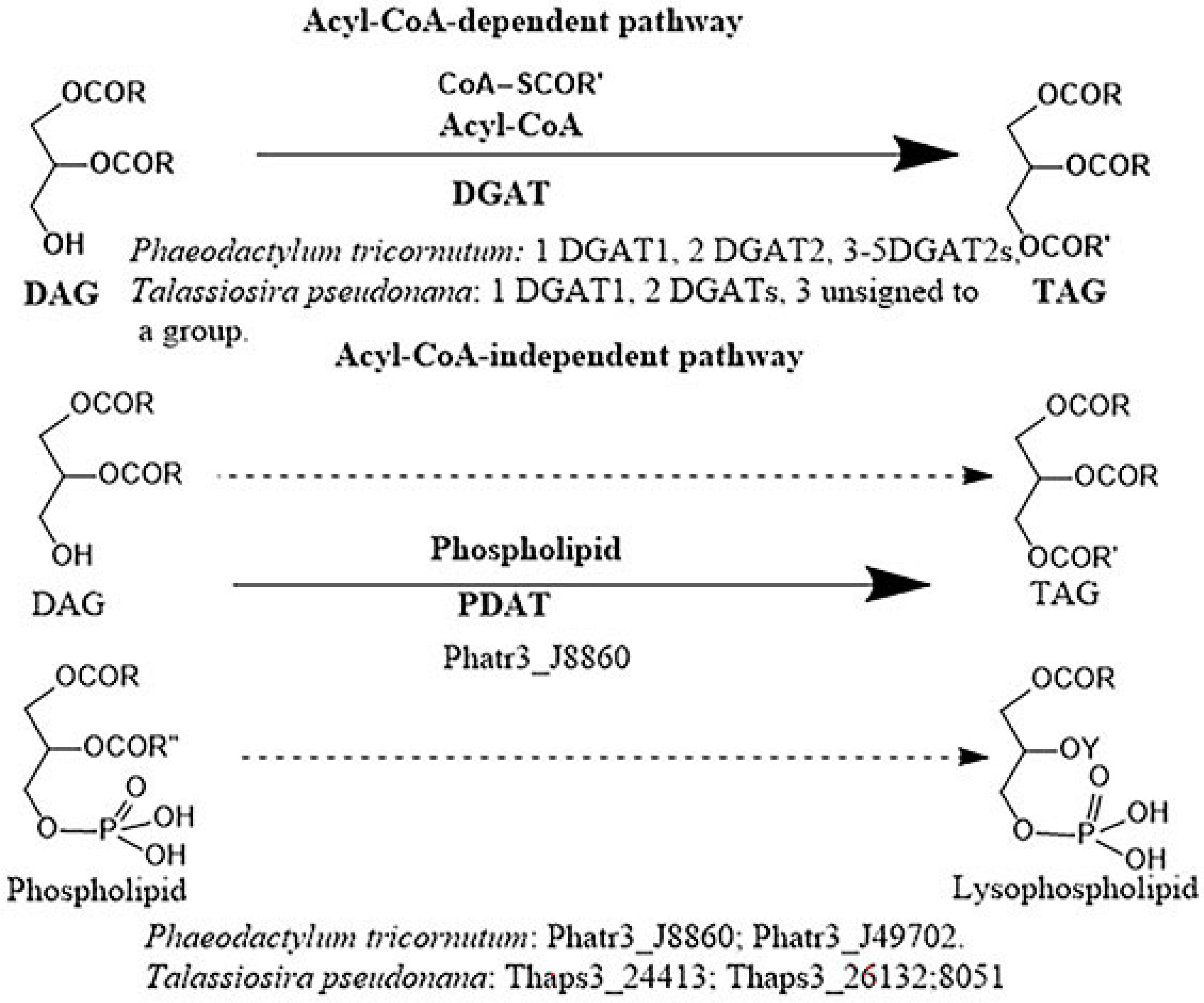

2.3.2. Triacylglycerols (TAGs)

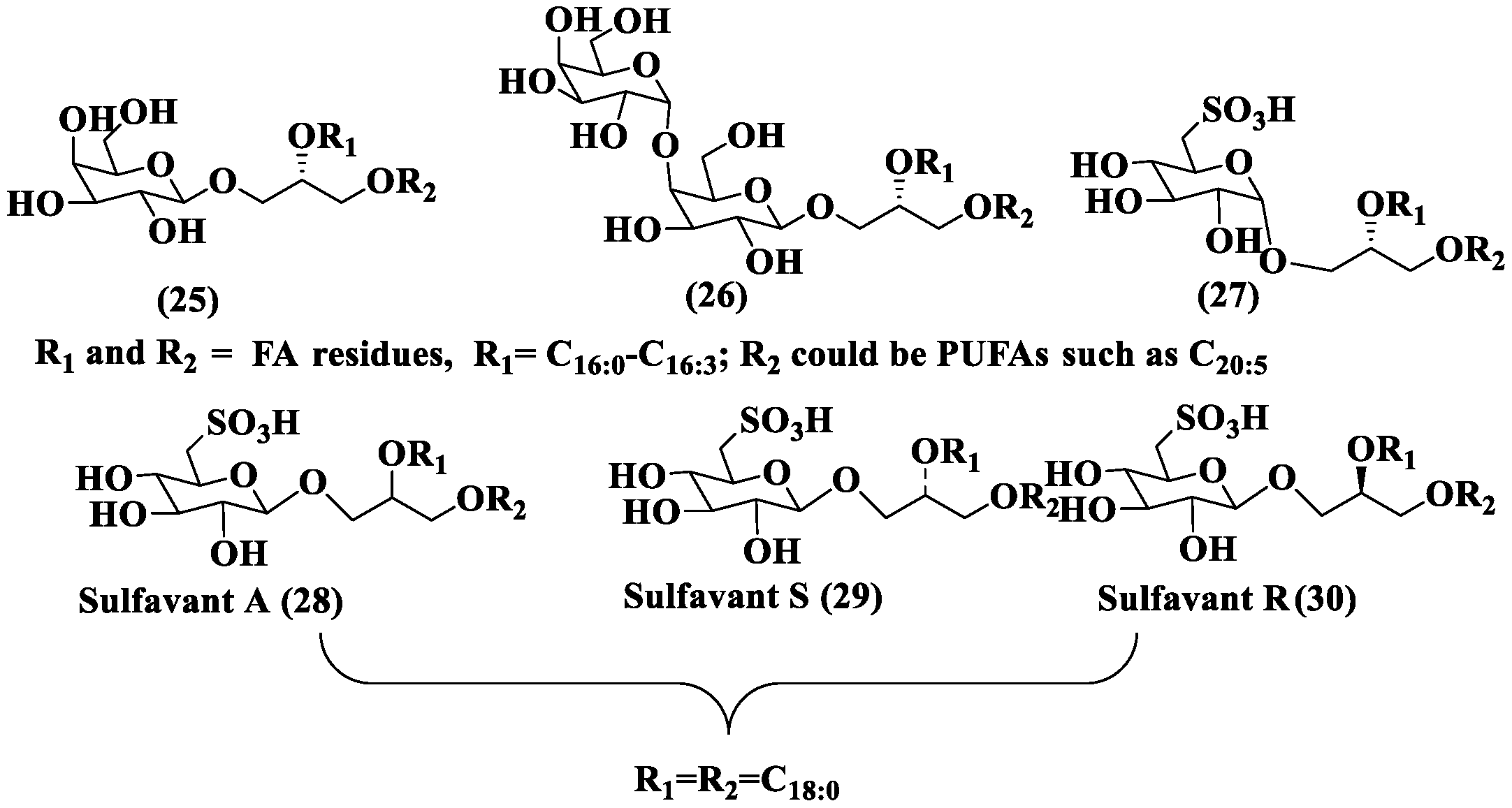

2.3.3. Glycolipids (GLs)

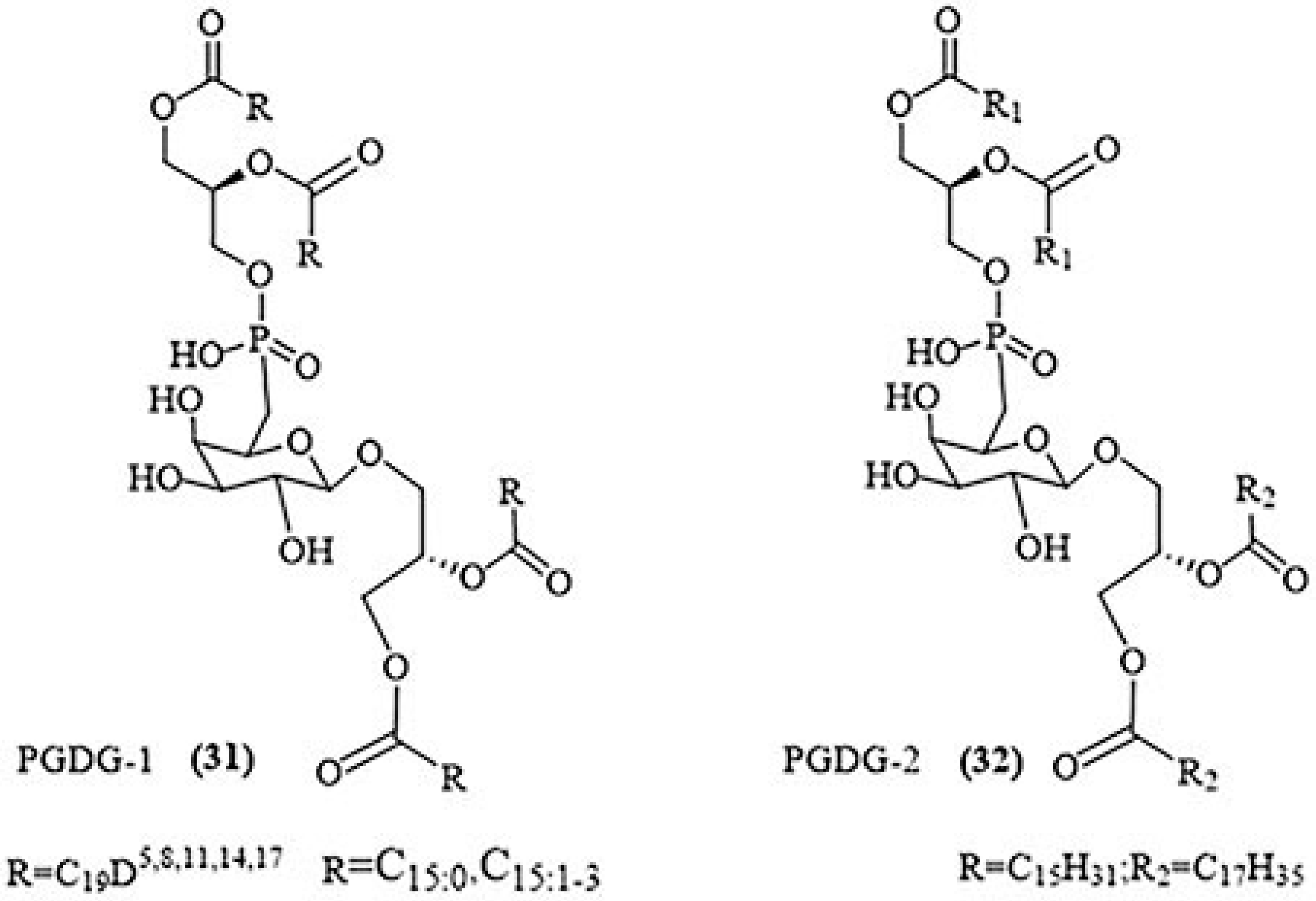

2.3.4. Phosphoglycolipids

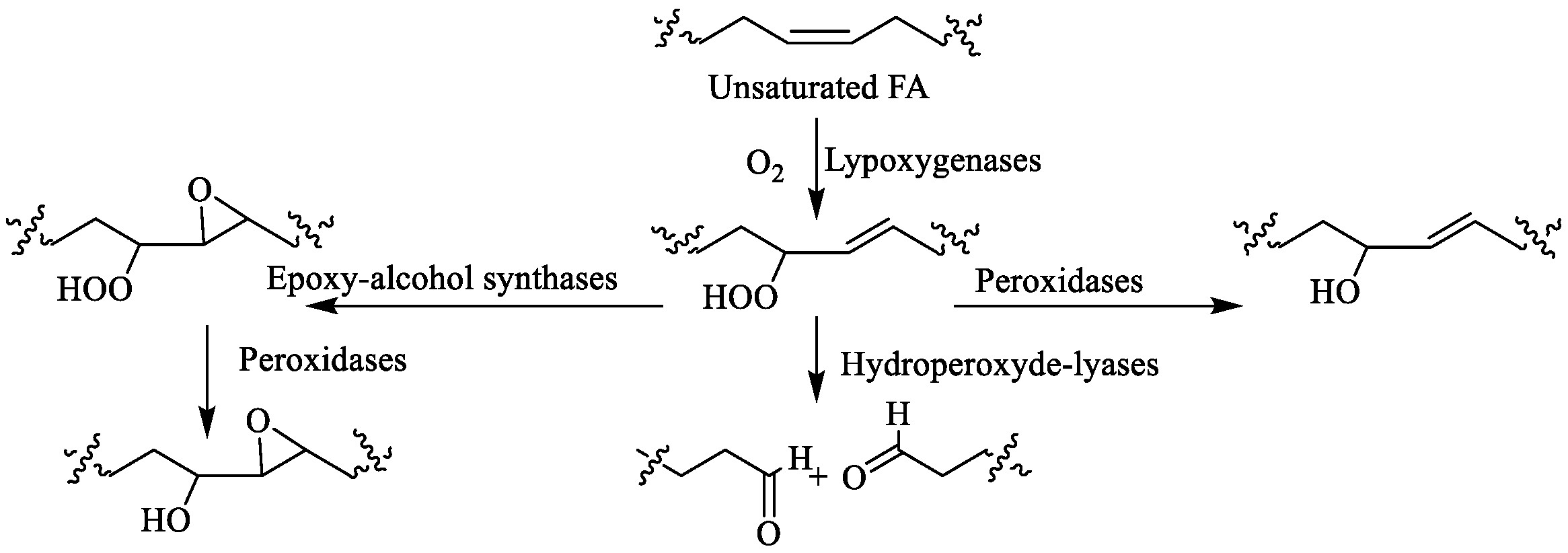

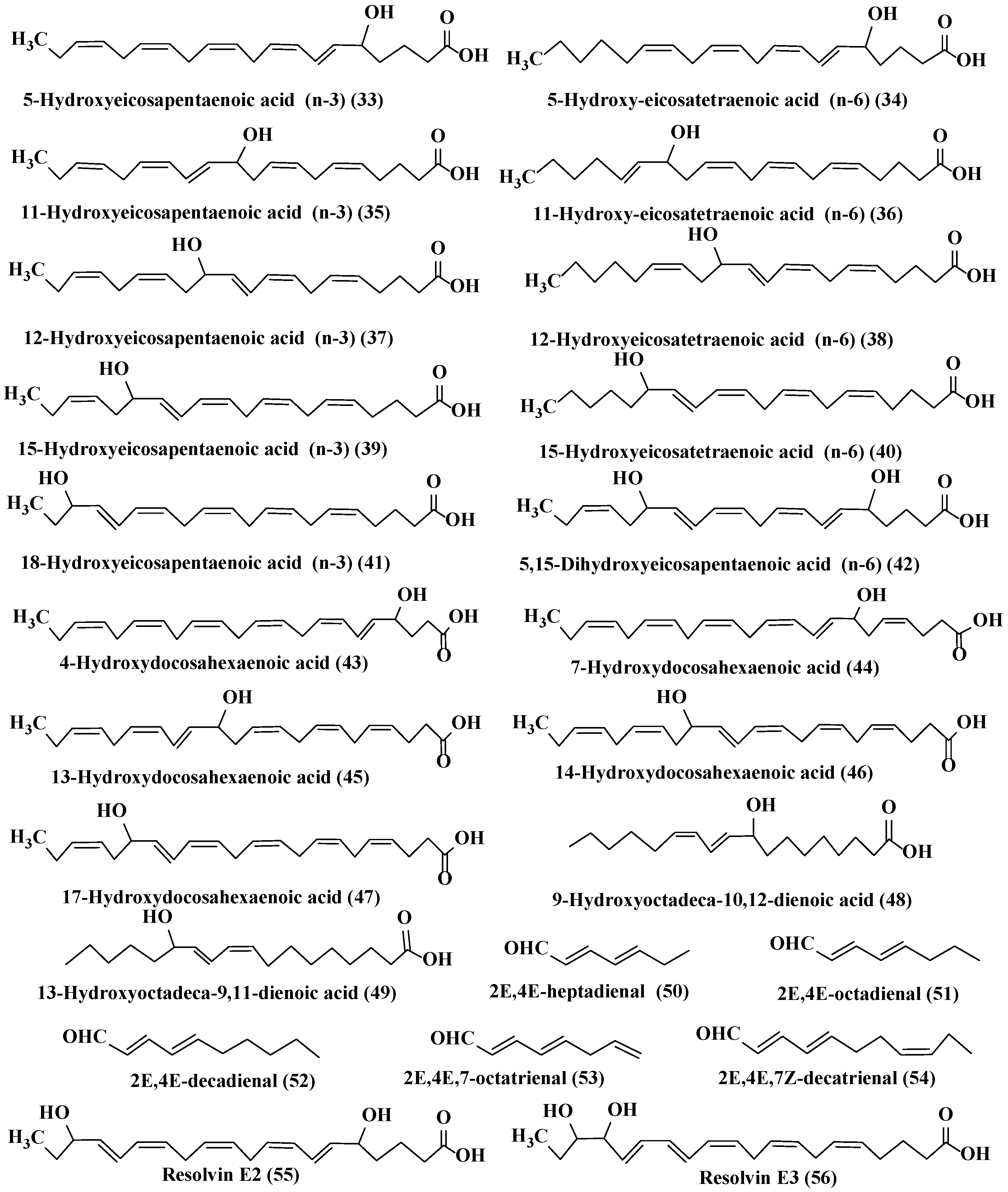

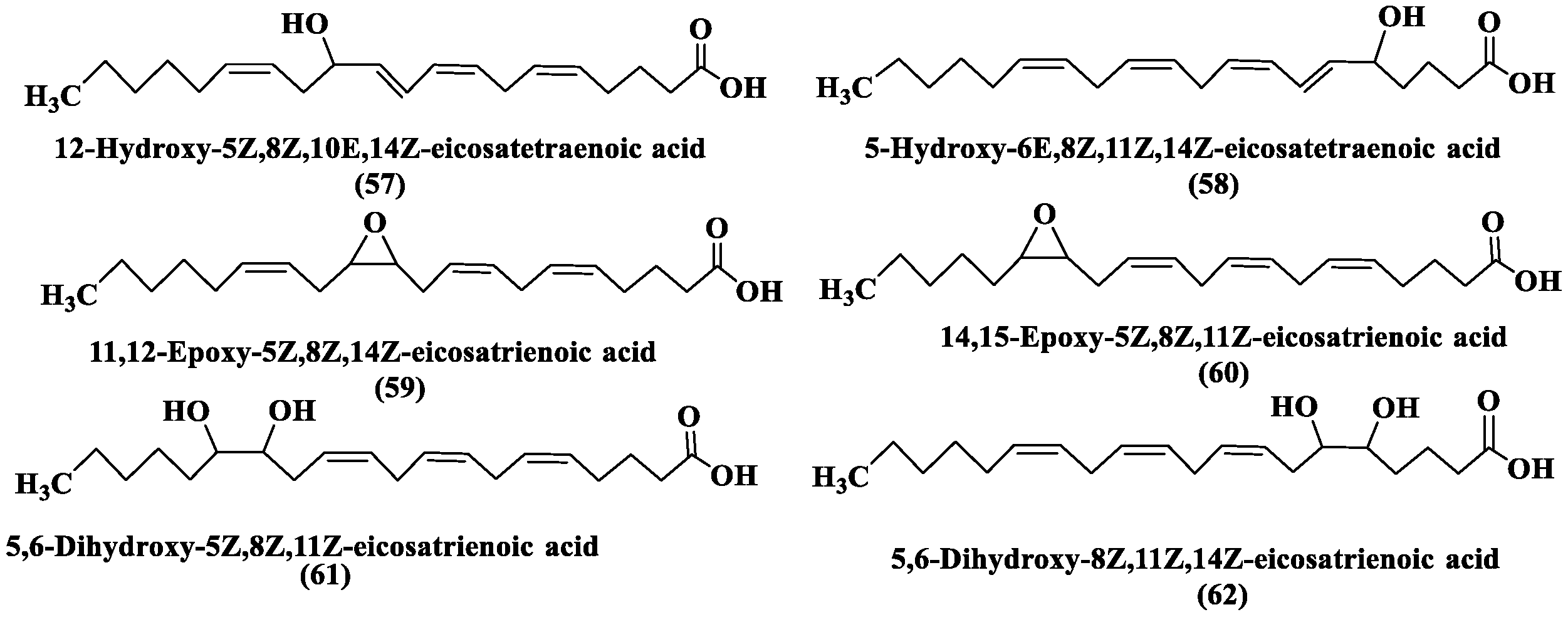

2.3.5. Oxylipins (OLs)

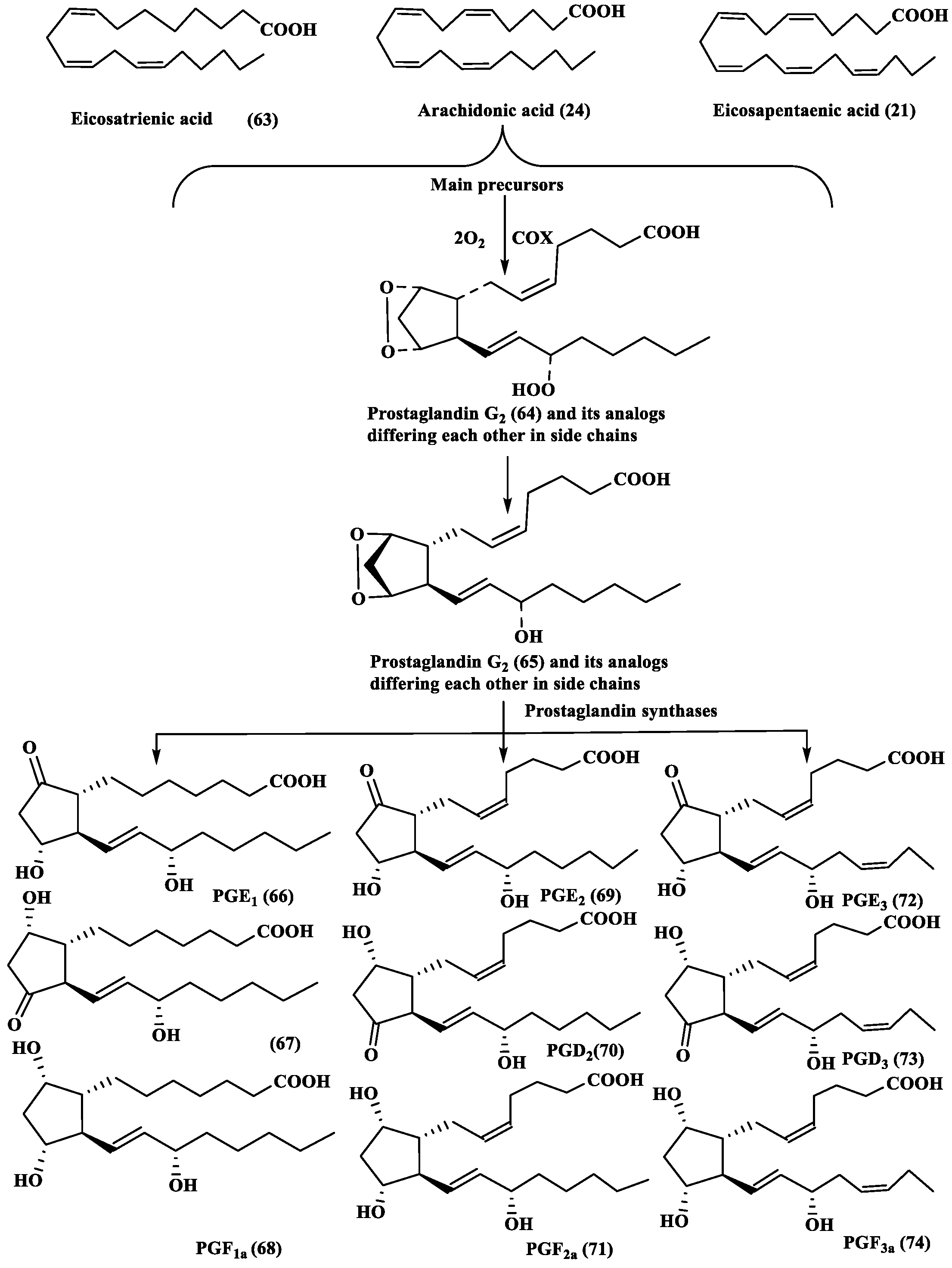

2.4. Prostaglandins (PGs)

3. Exometabolites

3.1. Sex Pheromones of Diatoms

3.2. Toxins

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stonik, V.A.; Stonik, I.V. Low-molecular-weight metabolites from diatoms: Structures, biological roles and biosynthesis. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3672–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoiston, A.S.; Ibarbalz, F.M.; Bittner, L.; Guidi, L.; Jahn, O.; Dutkiewicz, S.; Bowler, C. The evolution of diatoms and their biogeochemical functions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermeño, P.; Falkowski, P.G.; Romero, O.E.; Schaller, M.F.; Vallina, S.M. Continental erosion and the Cenozoic rise of marine diatoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4239–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Phillips, R.; Milo, R. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6506–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermeño, P. The geological story of marine diatoms and the last generation of fossil fuels. Perspect. Phycol. 2016, 3, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, D.; Butler, T.O.; Shuhaili, F.; Vaidyanathan, S. Diatoms for carbon sequestration and bio-based manufacturing. Biology 2020, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malviya, S.; Scalco, E.; Audic, S.; Vincent, F.; Veluchamy, A.; Poulain, J.; Wincker, P.; Iudicone, D.; de Vargas, C.; Bittner, L.; et al. Insights into global diatom distribution and diversity in the world’s ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1516–E1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlutdinova, A.; Gabidullin, Y.; Allaguvatova, R.; Gaysina, L. Diatoms in Kamchatka’s hot spring soils. Diversity 2020, 12, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, U.; Wietkamp, S.; Kretschmann, J.; Chacón, J.; Gottschling, M. Spatial fragmentation in the distribution of diatom endosymbionts from the taxonomically clarified dinophyte Kryptoperidinium triquetrum (=Kryptoperidinium foliaceum, Peridiniales). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonik, I.V.; Skriptsova, A.V. Pseudogomphonema lukinicum sp. nov. (Bacillariophyceae), a new endophytic diatom found inside multicellular red algae from the Northwest Pacific. Bot. Mar. 2024, 67, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Camillo, C.G.; Cerrano, C.; Romagnoli, T.; Calcinai, B. Living inside a sponge skeleton: The association of a sponge, a macroalga and a diatom. Symbiosis 2017, 71, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojko, M.; Listwan, S.; Goss, R.; Latowski, D. Structure and dynamics of the diatom chloroplast. In Diatom Photosynthesis: From Primary Production to Hgh-Value Molecules; Goessling, J.W., Serodio, J., Lavaud, J., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.G.; Vanormelingen, P. An inordinate fondness? The number, distributions, and origins of diatom species. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2013, 60, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medlin, L.K.; Kaczmarska, I. Evolution of the diatoms: V. Morphological and cytological support for the major clades and a taxonomic revision. Phycologia 2004, 43, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlin, L.K. Evolution of the diatoms: Major steps in their evolution and a review of the supporting molecular and morphological evidence. Phycologia 2016, 55, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirichine, L.; Rastogi, A.; Bowler, C. Recent progress in diatom genomics and epigenomics. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 36, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritano, C.; Ferrante, M.I.; Rogato, A. Marine natural products from microalgae: An-omics overview. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Wichuk, K.; Brynjólfsson, S. Developing diatoms for value-added products: Challenges and opportunities. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieri, P.; Carpi, S.; Esposito, R.; Costantini, M.; Zupo, V. Bioactive molecules from marine diatoms and their value for the nutraceutical industry. Nutrients 2023, 15, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Daboussi, F. Genetic and metabolic engineering in diatoms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczynska, P.; Jemiola-Rzeminska, M.; Strzalka, K. Photosynthetic pigments in diatoms. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5847–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yu, L.J.; Xu, C.; Tomizaki, T.; Zhao, S.; Umena, Y.; Chen, X.; Qin, X.; Xin, Y.; Suga, M.; et al. Structural basis for blue-green light harvesting and energy dissipation in diatoms. Science 2019, 363, eaav0365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wei, D.; Xie, J. Diatoms as cell factories for high-value products: Chrysolaminarin, eicosapentaenoic acid, and fucoxanthin. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wu, S.; Yang, G.; Pan, K.; Wang, L.; Hu, Z. A review on the progress, challenges and prospects in commercializing microalgal fucoxanthin. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Di Chen, D.; Tu, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z. Synthetic biology in microalgae towards fucoxanthin production for pharmacy and nutraceuticals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 220, 115958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichoński, J.; Chrzanowski, G. Microalgae as a source of valuable phenolic compounds and carotenoids. Molecules 2022, 27, 8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautermann, O.; Lyska, D.; Andersen-Ranberg, J.; Becker, M.; Frӧhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Gartmann, H.; Kramer, L.C.; Mayr, K.; Pieper, D.; Rij, L.M.; et al. An algal enzyme required for biosynthesis of the most abundant marine carotenoids. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaw9183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.K.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Han, J.C.; Yang, G.P.; Liu, T.Z.; Wang, H. Isolation and characterization of a neoxanthin synthase gene functioning in fucoxanthin biosynthesis of Phaeodactyum tricornutum. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Pan, Y.; Yin, W.; Liu, J.; Hu, H. A key gene, violaxanthin de-epoxidase-like 1, enhances fucoxanthin accumulation in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Cao, T.; Dautermann, O.; Buschbeck, P.; Cantrell, M.B.; Chen, Y.; Lein, C.D.; Shi, X.; Ware, M.A.; Yang, F.; et al. Green diatom mutants reveal an intricate biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, E2203708119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Bai, Y.; Buschbeck, P.; Tan, Q.; Cantrell, M.B.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, R.-Z.; Ries, N.K.; Shi, X.; et al. An unexpected hydratase synthesizes the green light-absorbing pigment fucoxanthin. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 3053–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. Brown is the new green: Discovery of an algal enzyme for the final step of fucoxanthin biosynthesis. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 2716–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giossi, C.E.; Kroth, P.G.; Lepetit, B. Xanthophyll cycling and fucoxanthin biosynthesis in the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum: Recent advances and new gene functions. Front. Photobiol. 2025, 3, 1680034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaichi, S. Distribution, biosynthesis, and function of carotenoids in oxygenic phototrophic algae. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Lan, J.C.W.; Kondo, A.; Hasunuma, T. Metabolic engineering and cultivation strategies for efficient production of fucoxanthin and related carotenoids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Græsholt, C.; Brembu, T.; Volpe, C.; Bartosova, Z.; Serif, M.; Winge, P.; Nymark, M. Zeaxanthin epoxidase 3 knockout mutants of the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum enable commercial production of the bioactive carotenoid diatoxanthin. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, C.; Pistelli, L.; Del Mondo, A.; Calabrone, L.; Fontana, A.; Noonan, D.M.; Albini, A.; Brunet, C. The Microalgal diatoxanthin inflects the cytokine storm in SARS-CoV-2 stimulated ACE2 overexpressing lung cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, Y.S.; Yusoff, F.M.; Tan, H.T.; Mazli, N.A.I.N.; Nazarudin, M.F.; Shaharuddin, N.A.; Omar, A.R.; Takahashi, K. Fucoxanthin production of microalgae under different culture factors: A systematic review. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, M.F.J.; Morais, A.M.M.B.; Morais, R.M.S.C. Carotenoids from marine microalgae: A valuable natural source for the prevention of chronic diseases. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5128–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.; Kim, M.B.; Park, Y.-K.; Lee, J.-Y. Health benefits of fucoxanthin in the prevention of chronic diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2020, 1865, 158618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasinghe, H.S.; Gunathilaka, M.D.T.L. A systematic review of fucoxanthin as a promising bioactive compound in drug development. Phytochem. Lett. 2024, 61, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastineau, R.; Turcotte, F.; Pouvreau, J.-B.; Morançais, M.; Fleurence, J.; Windarto, E.; Prasetiya, F.S.; Arsad, S.; Jaouen, P.; Babin, M.; et al. Marennine, promising blue pigments from a widespread Haslea diatom species complex. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 3161–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastineau, R.; Davidovich, N.A.; Hansen, G.; Rines, J.; Wulff, A.; Kaczmarska, I.; Ehrman, J.; Hermann, D.; Maumus, F.; Hardiviller, Y.; et al. Haslea ostrearia-like diatoms: Biodiversity out of the blue. Adv. Bot. Res. 2014, 71, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaise, C.; James, A.; Travers, M.A.; Zanella, M.; Badawi, M.; Mouget, J.L. Complex relationships between the blue pigment marennine and marine bacteria of the genus Vibrio. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaise, C.; Cormier, P.; Tremblay, R.; Audet, C.; Deschênes, J.S.; Turcotte, F.; François, C.; Seger, A.; Hallegraeff, G.; Lindquist, N.; et al. Harmful or harmless: Biological effects of marennine on marine organisms. Aquat. Toxicol. 2019, 209, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabed, N.; Verret, F.; Peticca, A.; Kryvoruchko, I.; Gastineau, R.; Bosson, O.; Séveno, J.; Davidovich, O.; Davidovich, N.; Witkowski, A.; et al. What was old is new again: The pennate diatom Haslea ostrearia (Gaillon) Simonsen in the multi-omic age. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M.; Baroroh, U.; Nuwarda, R.F.; Prasetiya, F.S.; Ishmayana, S.; Novianti, M.T.; Tohari, T.R.; Hardianto, A.; Subroto, T.; Mouget, J.-L.; et al. Theoretical and experimental studies on the evidence of 1,3-β-Glucan in marennine of Haslea ostrearia. Molecules 2023, 28, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebiri, I.; Jacquette, B.; Francezon, N.; Herbaut, M.; Latigui, A.; Bricaud, S.; Tremblay, R.; Pasetto, P.; Mouget, J.-L.; Dittmer, J. The polysaccharidic nature of the skeleton of marennine as determined by NMR spectroscopy. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latigui, A.; Jacquette, B.; Dittmer, J.; Bardeau, J.F.; Boivin, E.; Beaulieu, L.; Pasetto, P.; Mouget, J.L. Spectral properties of marennine-like pigments reveal minor differences between blue Haslea species and strains. Molecules 2024, 29, 5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehouri, M.; Pedron, E.; Genard, B.; Doiron, K.; Fortin, S.; Bélanger, W.; Deschênes, J.-S.; Tremblay, R. “Bleu VS Yellow”: Marennine and extracellular polysaccharides for potential application in cosmetic and pharmaceutical applications. Microbe 2025, 8, 100448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, W.; Saint-Louis, R.; Genard, B.; Deschênes, J.S.; Tremblay, R. Scalable purification of marennine and other exopolymers from diatom Haslea ostrearia’s “blue water”. Algal Res. 2025, 86, 103879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gügi, B.; Le Costaouec, T.; Burel, C.; Lerouge, P.; Helbert, W.; Bardor, M. Diatom-specific oligosaccharide and polysaccharide structures help to unravel biosynthetic capabilities in diatoms. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5993–6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.F.; Li, D.W.; Balamurugan, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.D.; Li, H.Y. Chrysolaminarin biosynthesis in the diatom is enhanced by overexpression of 1, 6-β-transglycosylase. Algal. Res. 2022, 66, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-F.; Li, D.-W.; Chen, T.-T.; Hao, T.-B.; Balamurugan, S.; Yang, W.-D.; Liu, J.-S.; Li, H.-Y. Overproduction of bioactive algal chrysolaminarin by the critical carbon flux regulator phosphoglucomutase. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 14, 1800220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrand, M.; Manandhar-Shrestha, K.; Abbriano, R. Effects of chrysolaminarin synthase knockdown in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: Implications of reduced carbohydrate storage relative to green algae. Algal Res. 2017, 23, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Río Bártulos, C.; Kroth, P.G. Diatom vacuolar 1, 6-β-transglycosylases can functionally complement the respective yeast mutants. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2016, 63, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Du, H.; Liu, Z.; Du, H.; Rashid, A.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Wang, S. Resolving the dynamics of chrysolaminarin regulation in a marine diatom: A physiological and transcriptomic study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 252, 126361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Gao, B.; Li, A.; Xiong, J.; Ao, Z.; Zhang, C. Preliminary characterization, antioxidant properties and production of chrysolaminarin from marine diatom Odontella aurita. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 4883–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yao, R.; He, X.S.; Liao, Z.H.; Liu, Y.T.; Gao, B.Y.; Zhang, C.-W.; Niu, J. Beneficial contribution of the microalga Odontella aurita to the growth, immune response, antioxidant capacity, and hepatic health of juvenile golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Aquaculture 2022, 555, 738206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, J.; Moro, T.R.; Winnischofer, S.M.B.; Colusse, G.A.; Tamiello, C.S.; Trombetta-Lima, M.; Noleto, G.R.; Dolga, A.M.; Duarte, M.E.R.; Noseda, M.D. Chemical structure and biological activity of the (1→3)-linked β-D-glucan isolated from marine diatom Conticribra weissflogii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Du, H.; Aslam, M.; Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Li, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Laminarin, a major polysaccharide in Stramenopiles. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasiborski, A.; Saxena, A.; Marella, T.K.; Loiseau, C.; Tiwari, A.; Ulmann, L. Chrysolaminarin metabolism in diatoms: Pathways, regulation, and biotechnological perspectives. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 3993–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, C.C.; Caramujo, M.J. The various roles of fatty acids. Molecules 2018, 23, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwagbo, U.; Bernstein, P.S. Understanding the roles of very-long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (VLC-PUFAs) in eye health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Han, Q.; Gao, X.; Gao, G. Conditions optimizing on the yield of biomass, total lipid, and valuable fatty acids in two strains of Skeletonema menzelii. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, N.N.; Zienkiewicz, K.; Vollheyde, K.; Feussner, I. Current trends to comprehend lipid metabolism in diatoms. Prog. Lipid Res. 2018, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Xu, M.; Di, X.; Brynjolfsson, S.; Fu, W. Exploring valuable lipids in diatoms. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprynskyy, M.; Monedeiro, F.; Monedeiro-Milanowski, M.; Nowak, Z.; Krakowska-Sieprawska, A.; Pomastowski, P.; Gadzala-Kopciuch, R.M.; Buszewski, B. Isolation of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid-EPA and docosahexaenoic acid-DHA) from diatom biomass using different extraction methods. Algal Res. 2022, 62, 102615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. The differential effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, G.; Rioux, V.; Legrand, P. The n-3 docosapentaenoic acid (DPA): A new player in the n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid family. Biochimie 2019, 159, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byelashov, O.A.; Sinclair, A.J.; Kaur, G. Dietary sources, current intakes, and nutritional role of omega-3 docosapentaenoic acid. Lipid technol. 2015, 27, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Han, W.; Jin, W.; Gao, S.; Zhou, X. Docosahexaenoic acid production by Schizochytrium sp.: Review and prospect. Food Biotechnol. 2021, 35, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, M.; Gupta, A.; Sahni, S. Schizochytrium sp. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 872–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laino, C.H.; Garcia, P.; Podestá, M.F.; Höcht, C.; Slobodianik, N.; Reinés, A. Fluoxetine potentiation of omega-3 fatty acid antidepressant effect: Evaluating pharmacokinetic and brain fatty acid-related aspects in rodents. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 103, 3316–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M.L.; Powers, S.; Napier, J.A.; Sayanova, O. Heterotrophic production of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids by trophically converted marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Luo, L.; Jouhet, J.; Rébeillé, F.; Maréchal, E.; Hu, H.; Pan, Y.; Tan, X.; Chen, Z.; You, L.; et al. Enhanced triacylglycerol production in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum by inactivation of a Hotdog-fold thioesterase gene using TALEN-based targeted mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remize, M.; Planchon, F.; Loh, A.N.; Le Grand, F.; Bideau, A.; Le Goic, N.; Fleury, E.; Miner, P.; Corvaisier, R.; Volety, A.; et al. Study of synthesis pathways of the essential polyunsaturated fatty acid 20: 5n-3 in the diatom Chaetoceros muelleri using 13C-isotope labeling. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayanova, O.; Mimouni, V.; Ulmann, L.; Morant-Manceau, A.; Pasquet, V.; Schoefs, B.; Napier, J.A. Modulation of lipid biosynthesis by stress in diatoms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, A.; Vieira, F.R.J.; Deton-Cabanillas, A.-F.; Veluchamy, A.; Cantrel, C.; Wang, G.; Vanormelingen, P.; Bowler, C.; Piganeau, G.; Hu, H.; et al. A genomics approach reveals the global genetic polymorphism, structure, and functional diversity of ten accessions of the marine model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. ISME J. 2020, 14, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumier, T.; Yang, F.; Manirakiza, E.; Ait-Mohamed, O.; Wu, Y.; Chandola, U.; Jesus, B.; Piganeau, G.; Groisillier, A.; Tirichine, L. Genome-wide assessment of genetic diversity and transcript variations in 17 accessions of the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. ISME Commun. 2024, 4, ycad008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murison, V.; Hérault, J.; Marchand, J.; Ulmann, L. Diatom triacylglycerol metabolism: From carbon fixation to lipid droplet degradation. Biol. Rev. 2025, 100, 1423–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ding, W.; Hu, H.; Lui, J. Lipid production is more than doubled by manipulating a diacylglycerol acyltransferase in algae. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Nojima, D.; Yoshino, T.; Tanaka, T. Structure and properties of oil bodies in diatoms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupette, J.; Jaussaud, A.; Seddiki, K.; Morabito, C.; Brugière, S.; Schaller, H.; Kuntz, M.; Putaux, J.-L.; Jouneau, P.-H.; Rèbeillè, F.; et al. The architecture of lipid droplets in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Algal Res. 2019, 38, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, K.; Oishi, R.; Yoshida, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Suzuki, I. Stramenopile-type lipid droplet protein functions as a lipid droplet scaffold protein in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2023, 64, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zienkiewicz, K.; Zienkiewicz, A. Degradation of lipid droplets in plants and algae—Right time, many paths, one goal. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 579019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, E.; Silva, J.; Mendonça, S.H.; Abreu, M.H.; Domingues, M.R. Lipidomic approaches towards deciphering glycolipids from microalgae as a reservoir of bioactive lipids. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, G.; Lauritano, C. Microalgae with immunomodulatory activities. Mar. Drugs 2019, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, E.; Cutignano, A.; Pagano, D.; Gallo, C.; Barra, G.; Nuzzo, G.; Sansone, C.; Ianora, A.; Urbanek, K.; Fenoglio, D.; et al. A new marine-derived sulfoglycolipid triggers dendritic cell activation and immune adjuvant response. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaco, M.; Fioretto, L.; Nuzzo, G.; Fontana, A.; Manzo, E. Short gram-scale synthesis of Sulfavant A. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 2728–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzo, G.; Manzo, E.; Ziaco, M.; Fioretto, L.; Campos, A.M.; Gallo, C.; d’Ippolito, G.; Fontana, A. UHPLC-MS Method for the Analysis of the Molecular Adjuvant Sulfavant A. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, C.; Manzo, E.; Barra, G.; Fioretto, L.; Ziaco, M.; Nuzzo, G.; d’Ippolito, G.; Ferrera, F.; Contini, P.; Castiglia, D.; et al. Sulfavant A as the first synthetic TREM2 ligand discloses a homeostatic response of dendritic cells after receptor engagement. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barra, G.; Gallo, C.; Carbone, D.; Ziaco, M.; Dell’Isola, M.; Affuso, M.; Manzo, E.; Nuzzo, G.; Fioretto, L.; d’Ippolito, G.; et al. The immunoregulatory effect of the TREM2-agonist Sulfavant A in human allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1050113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioretto, L.; Ziaco, M.; Gallo, C.; Nuzzo, G.; d’Ippolito, G.; Lupetti, P.; Paccagnini, E.; Gentile, M.; Dellagreca, M.; Appavou, M.-S.; et al. Direct evidence of the impact of aqueous self-assembly on biological behavior of amphiphilic molecules: The case study of molecular immunomodulators sulfavants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 611, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, E.; Gallo, C.; Sartorius, R.; Nuzzo, G.; Sardo, A.; De Berardinis, P.; Fontana, A.; Cutignano, A. Immunostimulatory phosphatidylmonogalactosyldiacylglycerols (PGDG) from the marine diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii: Inspiration for a novel synthetic toll-like receptor 4 agonist. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, C.; Barra, G.; Saponaro, M.; Manzo, E.; Fioretto, L.; Ziaco, M.; Nuzzo, G.; d’Ippolito, G.; De Palma, R.; Fontana, A. A new bioassay platform design for the discovery of small molecules with anticancer immunotherapeutic activity. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stonik, V.A.; Stonik, I.V. Carbohydrate-containing low molecular weight metabolites of microalgae. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osawa, T.; Fujikawa, K.; Shimamoto, K. Structures, functions, and syntheses of glycero-glycophospholipids. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1353688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.M.; Mayer, V.A.; Swanson-Mungerson, M.; Pierce, M.L.; Rodríguez, A.D.; Nakamura, F.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Marine pharmacology in 2019–2021: Marine compounds with antibacterial, antidiabetic, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antiprotozoal, antituberculosis and antiviral activities; affecting the immune and nervous systems, and other miscellaneous mechanisms of action. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.; Freitas, M.; Branco, P.S. Phosphate-containing glycolipids: A review on synthesis and bioactivity. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202400315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruocco, N.; Albarano, L.; Esposito, R.; Zupo, V.; Costantini, M.; Ianora, A. Multiple roles of diatom-derived oxylipins within marine environments and their potential biotechnological applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettner, J.; Werner, M.; Meyer, N.; Werz, O.; Pohnert, G. Survey of the C20 and C22 oxylipin family in marine diatoms. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cózar, A.; Morillo-García, S.; Ortega, M.J.; Li, Q.P.; Bartual, A. Macroecological patterns of the phytoplankton production of polyunsaturated aldehydes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Rettner, J.; Werner, M.; Werz, O.; Pohnert, G. Algal oxylipins mediate the resistance of diatoms against algicidal bacteria. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orefice, I.; Di Dato, V.; Sardo, A.; Lauritano, C.; Romano, G. Lipid mediators in marine diatoms. Aquat. Ecol. 2022, 56, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritano, C.; Romano, G.; Roncalli, V.; Amoresano, A.; Fontanarosa, C.; Bastianini, M.; Braga, F.; Carotenuto, Y.; Ianora, A. New oxylipins produced at the end of a diatom bloom and their effects on copepod reproductive success and gene expression levels. Harmful Algae 2016, 55, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E.; d’Ippolito, G.; Fontana, A.; Sarno, D.; D’Alelio, D.; Busseni, G.; Ianora, A.; von Elert, E.; Carotenuto, Y. Density-dependent oxylipin production in natural diatom communities: Possible implications for plankton dynamics. ISME J. 2020, 14, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Costanzo, F.; Di Dato, V.; Ianora, A.; Romano, G. Prostaglandins in marine organisms: A review. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Dato, V.; Orefice, I.; Amato, A.; Fontanarosa, C.; Amoresano, A.; Cutignano, A.; Ianora, A.; Romano, G. Animal-like prostaglandins in marine microalgae. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1722–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbarinaldi, R.; Di Costanzo, F.; Orefice, I.; Romano, G.; Carotenuto, Y.; Di Dato, V. Prostaglandin pathway activation in the diatom Skeletonema marinoi under grazer pressure. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 196, 106395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Dato, V.; Di Costanzo, F.; Barbarinaldi, R.; Perna, A.; Ianora, A.; Romano, G. Unveiling the presence of biosynthetic pathways for bioactive compounds in the Thalassiosira rotula transcriptome. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Dato, V.; Barbarinaldi, R.; Amato, A.; Di Costanzo, F.; Fontanarosa, C.; Perna, A.; Amoresano, A.; Esposito, F.; Cutignano, A.; Ianora, A.; et al. Variation in prostaglandin metabolism during growth of the diatom Thalassiosira rotula. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutolo, E.A.; Campitiello, R.; Di Dato, V.; Orefice, I.; Angstenberger, M.; Cutolo, M. Marine phytoplankton bioactive lipids and their perspectives in clinical inflammation. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, J.; Frenkel, J.; Devos, V.; Sabbe, K.; Paul, C.; Rempt, M.; Inze, D.; Pohnert, G.; Vuylsteke, M.; Vyverman, W. Metabolomics enables the structure elucidation of a diatom sex pheromone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembke, C.; Stettin, D.; Speck, F.; Ueberschaar, N.; De Decker, S.; Vyverman, W.; Pohnert, G. Attraction pheromone of the benthic diatom Seminavis robusta: Studies on structure-activity relationships. J. Chem. Ecol. 2018, 44, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneure, E.; De Baets, A.; De Decker, S.; Van den Berge, K.; Clement, L.; Vyverman, W.; Mangelinckx, S. Altering the sex pheromone cyclo (L-Pro-L-Pro) of the diatom Seminavis robusta towards a chemical probe. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeys, S.; Frenkel, J.; Lembke, C.; Gillard, J.T.; Devos, V.; Van den Berge, K.; Bouillon, B.; Huysman, M.J.J.; De Decker, S.; Scharf, J.; et al. A sex-inducing pheromone triggers cell cycle arrest and mate attraction in the diatom Seminavis robusta. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

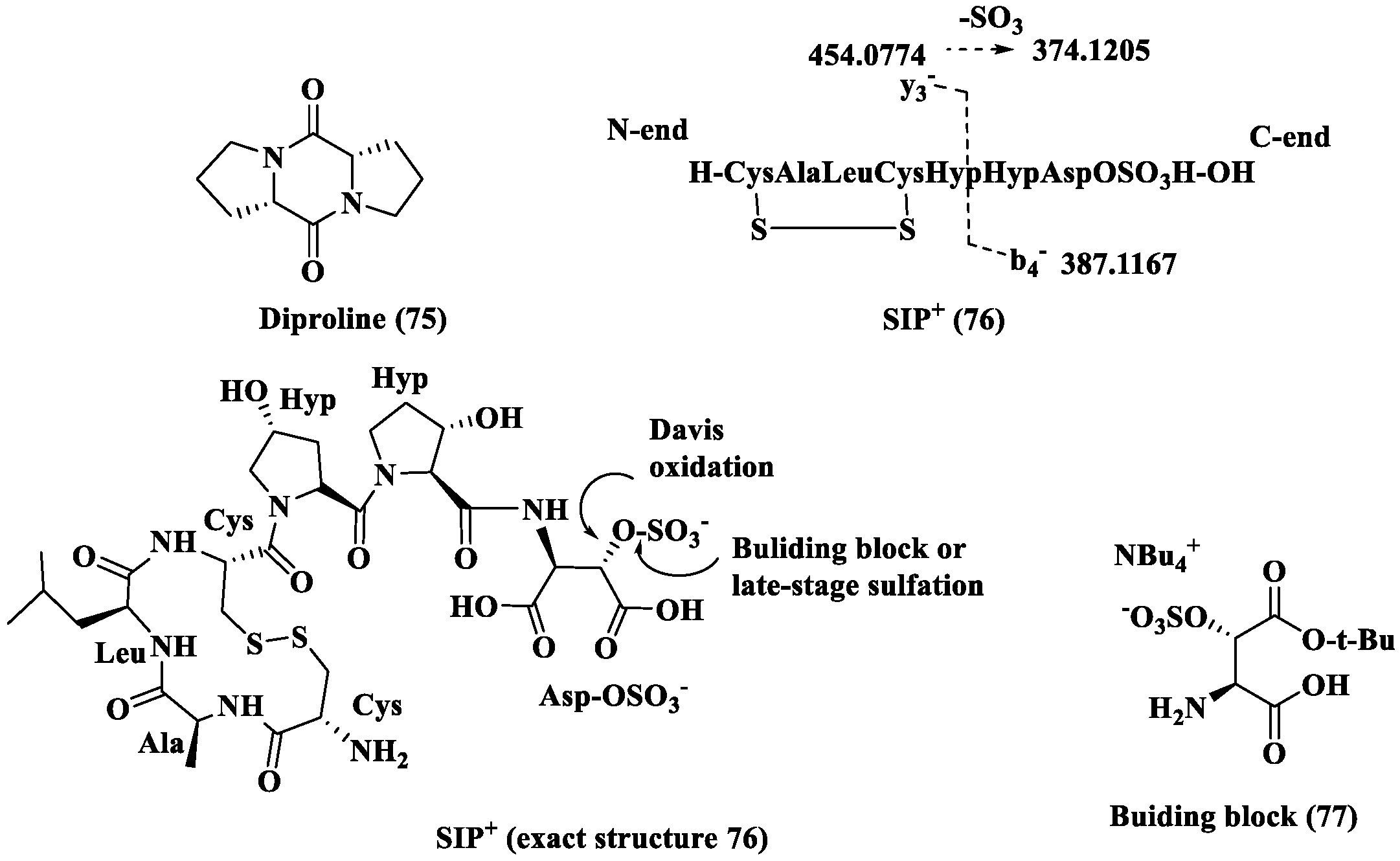

- Klapper, F.A.; Kiel, C.; Bellstedt, P.; Vyverman, W.; Pohnert, G. Structure elucidation of the first sex-inducing pheromone of a diatom. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202307165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.M.; Schwartz, B.D.; Gardiner, M.G.; Malins, L.R. Total synthesis of a peptide diatom sex pheromone bearing a sulfated aspartic acid. Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 6803–6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapper, F.A.; Pohnert, G. Recent advances in understanding the sex pheromone-mediated communication of diatoms. ChemPlusChem 2025, 90, e202500224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapper, F.; Audoor, S.; Vyverman, W.; Pohnert, G. Pheromone mediated sexual reproduction of pennate diatom Cylindrotheca closterium. J. Chem. Ecol. 2021, 47, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.T.; Vitale, L.; Entrambasaguas, L.; Anestis, K.; Fattorini, N.; Romano, F.; Minucci, C.; De Luca, P.; Biffali, E.; Vyverman, W.; et al. MRP3 is a sex determining gene in the diatom Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

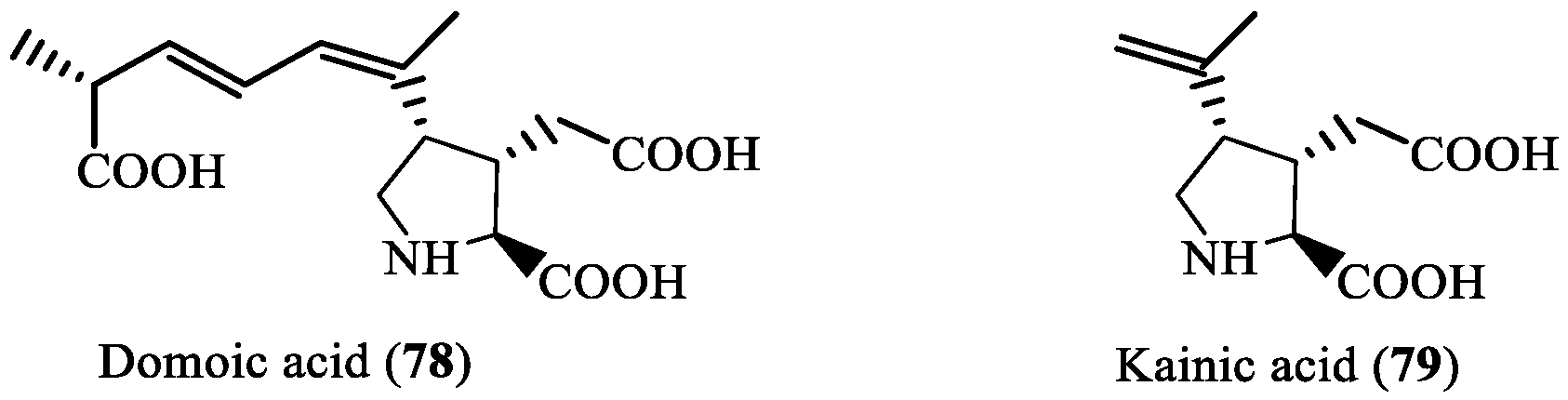

- Stonik, V.A.; Stonik, I.V. Marine excitatory amino acids: Structure, properties, biosynthesis and recent approaches to their syntheses. Molecules 2020, 25, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, O.M. Domoic acid toxicologic pathology: A review. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 180–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.S.; Hubbard, K.A.; Lundholm, N.; Montresor, M.; Leaw, C.P. Pseudo-nitzschia, Nitzschia, and domoic acid: New research since 2011. Harmful Algae 2018, 79, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunson, J.K.; Thukral, M.; Ryan, J.P.; Anderson, C.R.; Kolody, B.C.; James, C.C.; Chavez, F.P.; Leaw, C.P.; Rabines, A.J.; Venepally, P.; et al. Molecular forecasting of domoic acid during a pervasive toxic diatom bloom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319177121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

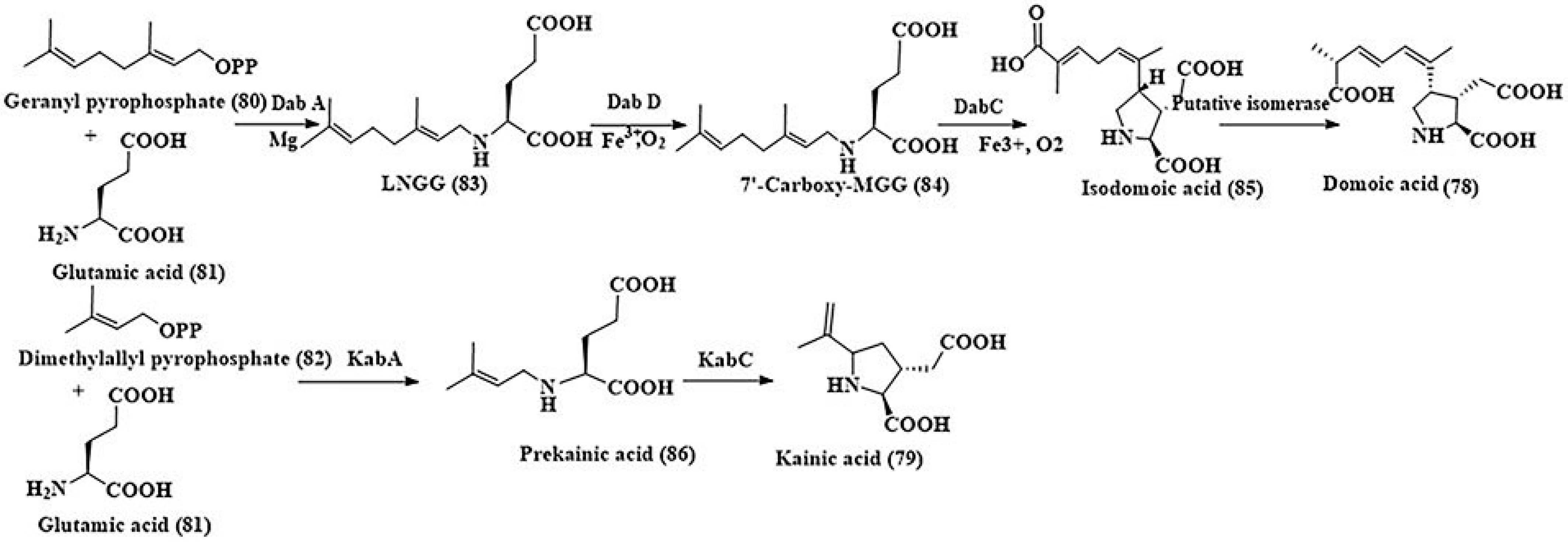

- Brunson, J.K.; McKinnie, S.M.; Chekan, J.R.; McCrow, J.P.; Miles, Z.D.; Bertrand, E.M.; Bielinski, V.A.; Luhavaya, H.; Oborník, M.; Smith, G.J.; et al. Biosynthesis of the neurotoxin domoic acid in a bloom-forming diatom. Science 2018, 361, 1356–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeno, Y.; Kotaki, Y.; Terada, R.; Cho, Y.; Konoki, K.; Yotsu-Yamashita, M. Six domoic acids related compounds from the red alga, Chondria armata, and domoic acid biosynthesis by the diatom, Pseudo-nitzchia multiseries. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, T.S.; Brunson, J.K.; Maeno, Y.; Terada, R.; Allen, A.E.; Yotsu-Yamashita, M.; Chekan, J.R.; Moore, B.S. Domoic acid biosynthesis in the red alga Chondria armata suggests a complex evolutionary history for toxin production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117407119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlisch, C.; Shemi, A.; Barak-Gavish, N.; Schatz, D.; Vardi, A. Algal blooms in the ocean: Hot spots for chemically mediated microbial interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammilehto, A.; Nielsen, T.G.; Krock, B.; Møller, E.F.; Lundholm, N. Induction of domoic acid production in the toxic diatom Pseudo-nitzschia seriata by calanoid copepods. Aquat. Toxicol. 2015, 159, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harðardóttir, S.; Wohlrab, S.; Hjort, D.M.; Krock, B.; Nielsen, T.G.; John, U.; Lundholm, N. Transcriptomic responses to grazing reveal the metabolic pathway leading to the biosynthesis of domoic acid and highlight different defense strategies in diatoms. BMC Mol. Biol. 2019, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | MW (kDa) | Branching | Yeld (%) | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | 10 | β-1,6-branching | >14 | [23] |

| Odontella aurita | 7.75 | β-1,6-branching | 48.1 | [23,58] |

| Skeletonema costatum | 6–13 | β-1,6-branching and β-1,2-branchings | 32 | [52] |

| Staurontis amphioxys | 4 | β-1,6-branching and β-1,2-branchings | nd | [52] |

| Pinnularia viridis | >10 | β-1,6-branching and β-1,2-branchings | nd | [52] |

| Stephanodiscus meueri | 40 | β-1,6-branching | 0.5 | [52] |

| Stephanodiscus meueri | 2–6 | β-1,6-branching | 0.6 | [52] |

| Thalassiosira weissflogii | 5–13 | No branching | nd | [52] |

| Chaetoceros debilis | 4.9 | Highly branching, β-1,6-branching | 10 | [52] |

| Conticribra weissflogii | 11.7 | Low proportion of β-1,6-branchings | 29.9 | [60] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stonik, V.A.; Stonik, I.V. Some Bioactive Natural Products from Diatoms: Structures, Biosyntheses, Biological Roles, and Properties: 2015–2025. Mar. Drugs 2026, 24, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010023

Stonik VA, Stonik IV. Some Bioactive Natural Products from Diatoms: Structures, Biosyntheses, Biological Roles, and Properties: 2015–2025. Marine Drugs. 2026; 24(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleStonik, Valentin A., and Inna V. Stonik. 2026. "Some Bioactive Natural Products from Diatoms: Structures, Biosyntheses, Biological Roles, and Properties: 2015–2025" Marine Drugs 24, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010023

APA StyleStonik, V. A., & Stonik, I. V. (2026). Some Bioactive Natural Products from Diatoms: Structures, Biosyntheses, Biological Roles, and Properties: 2015–2025. Marine Drugs, 24(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010023