Bioprospecting Sponge-Associated Microbes for Antimicrobial Compounds

Abstract

:1. Introduction

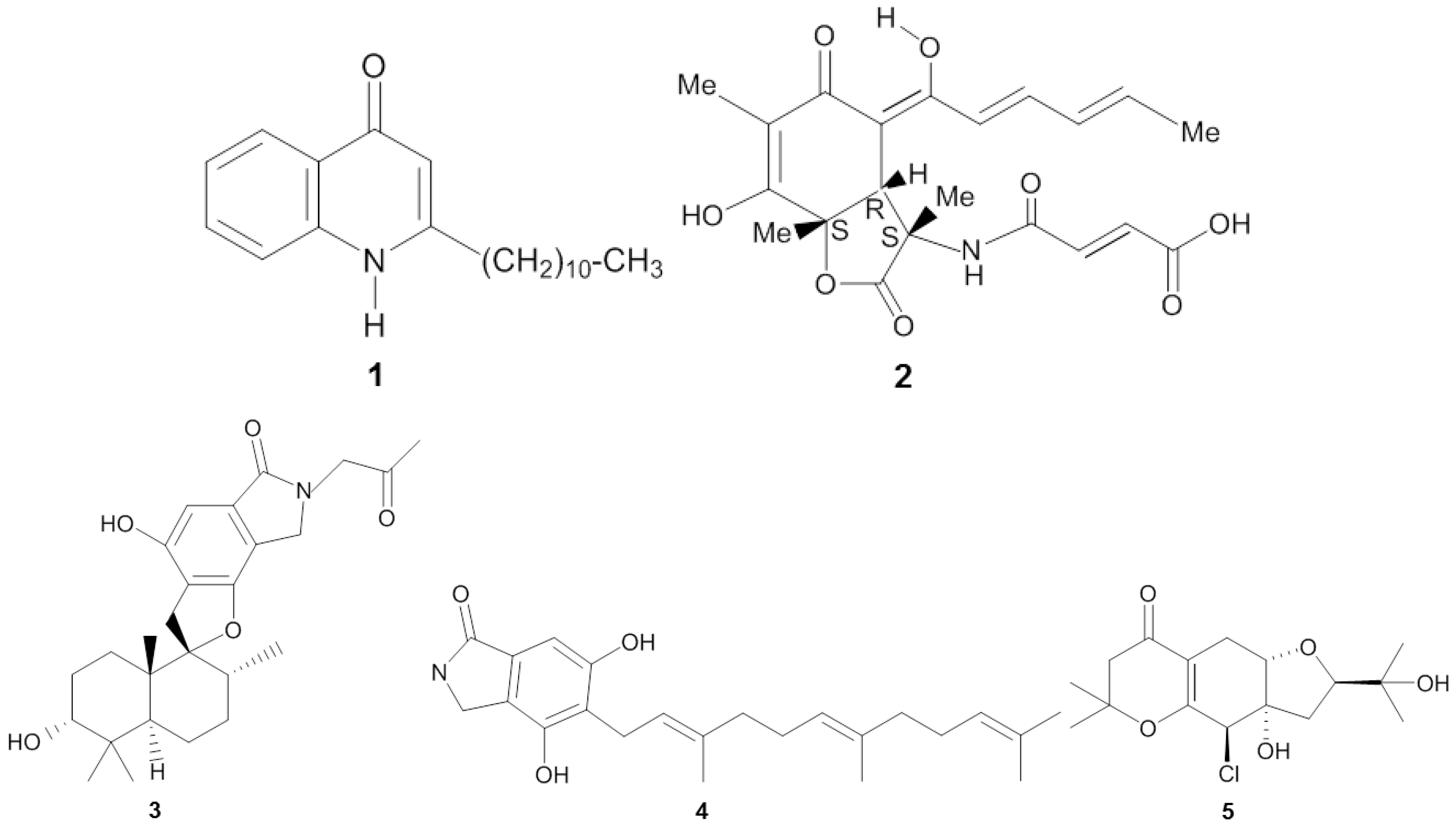

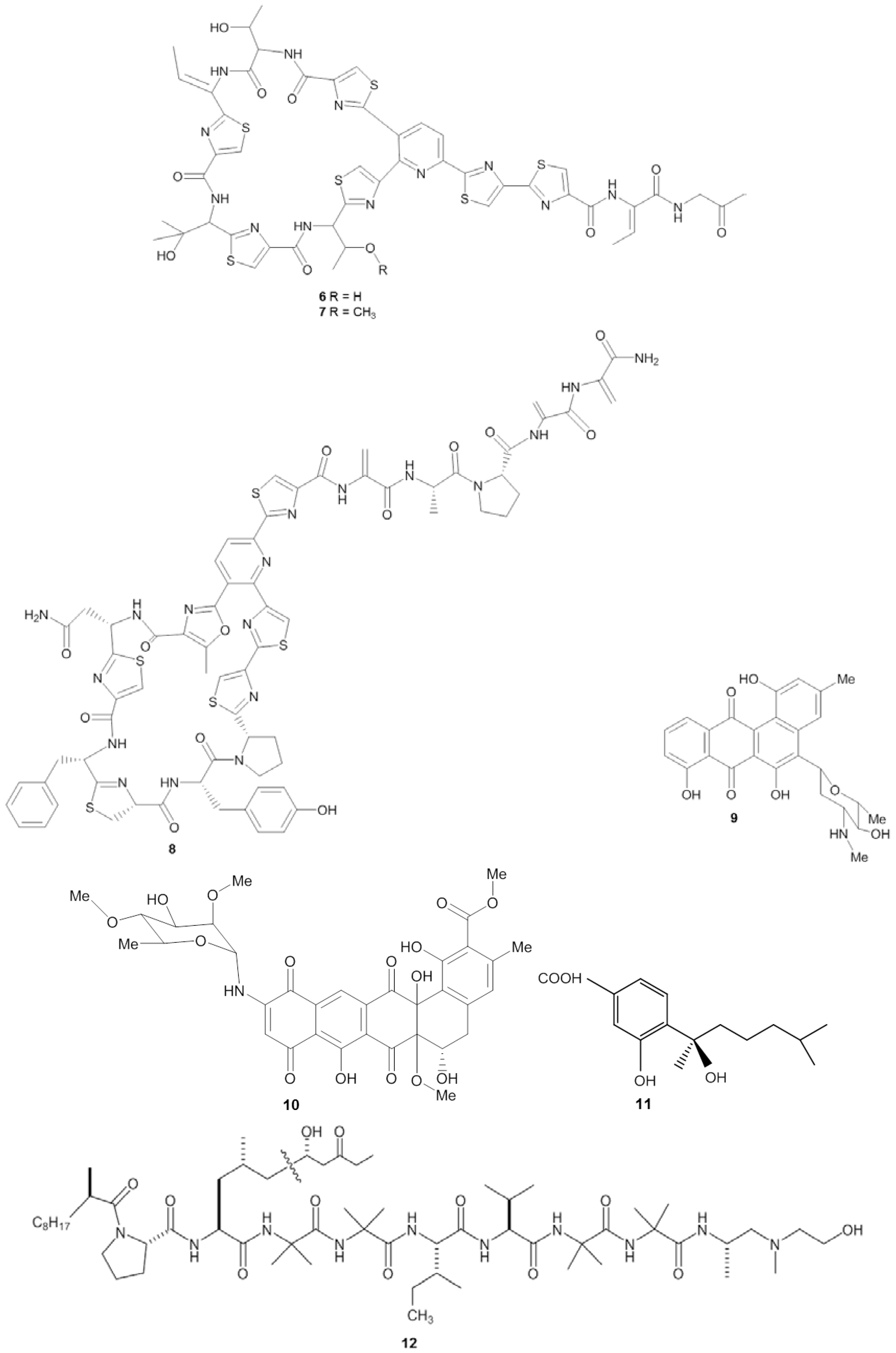

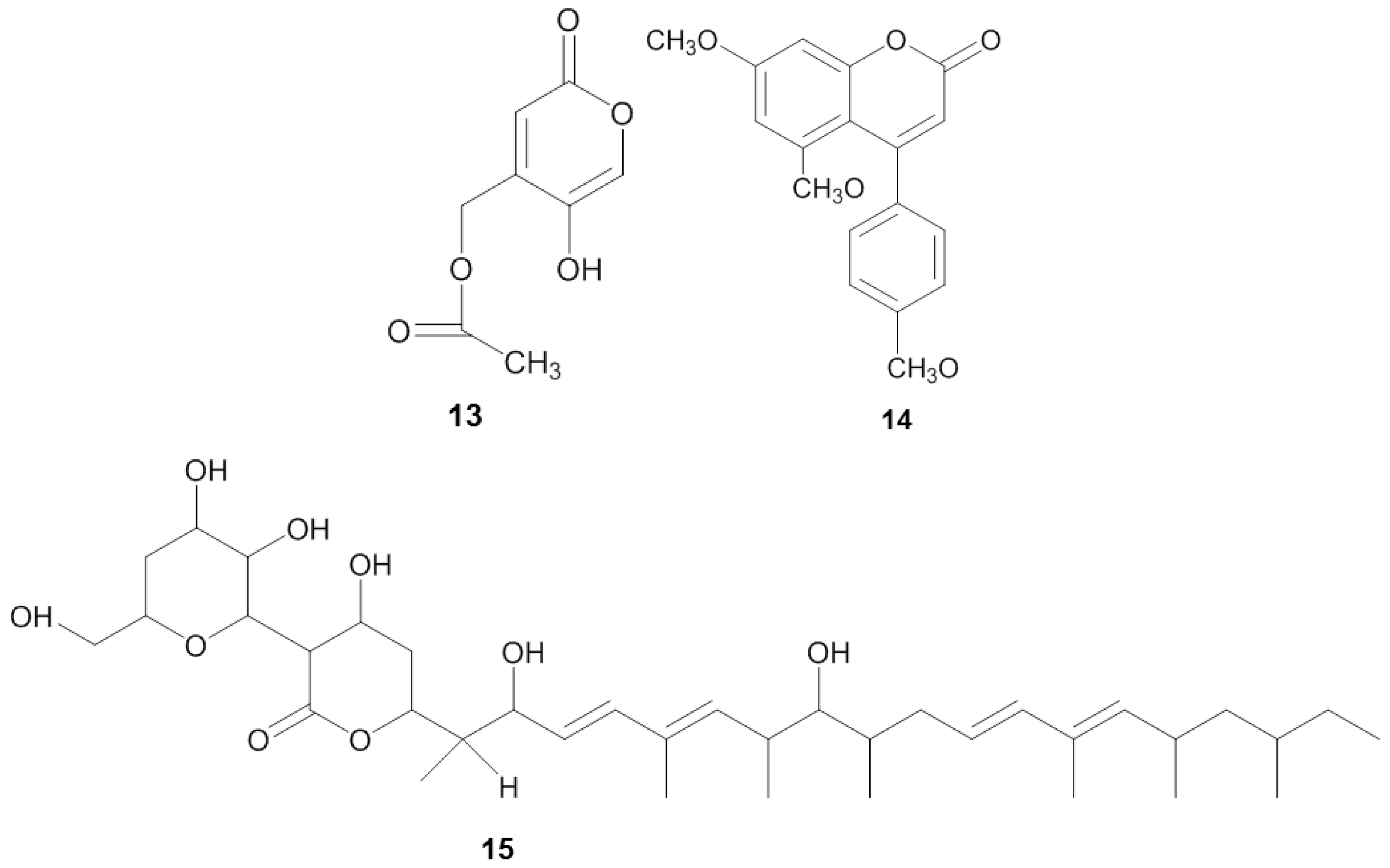

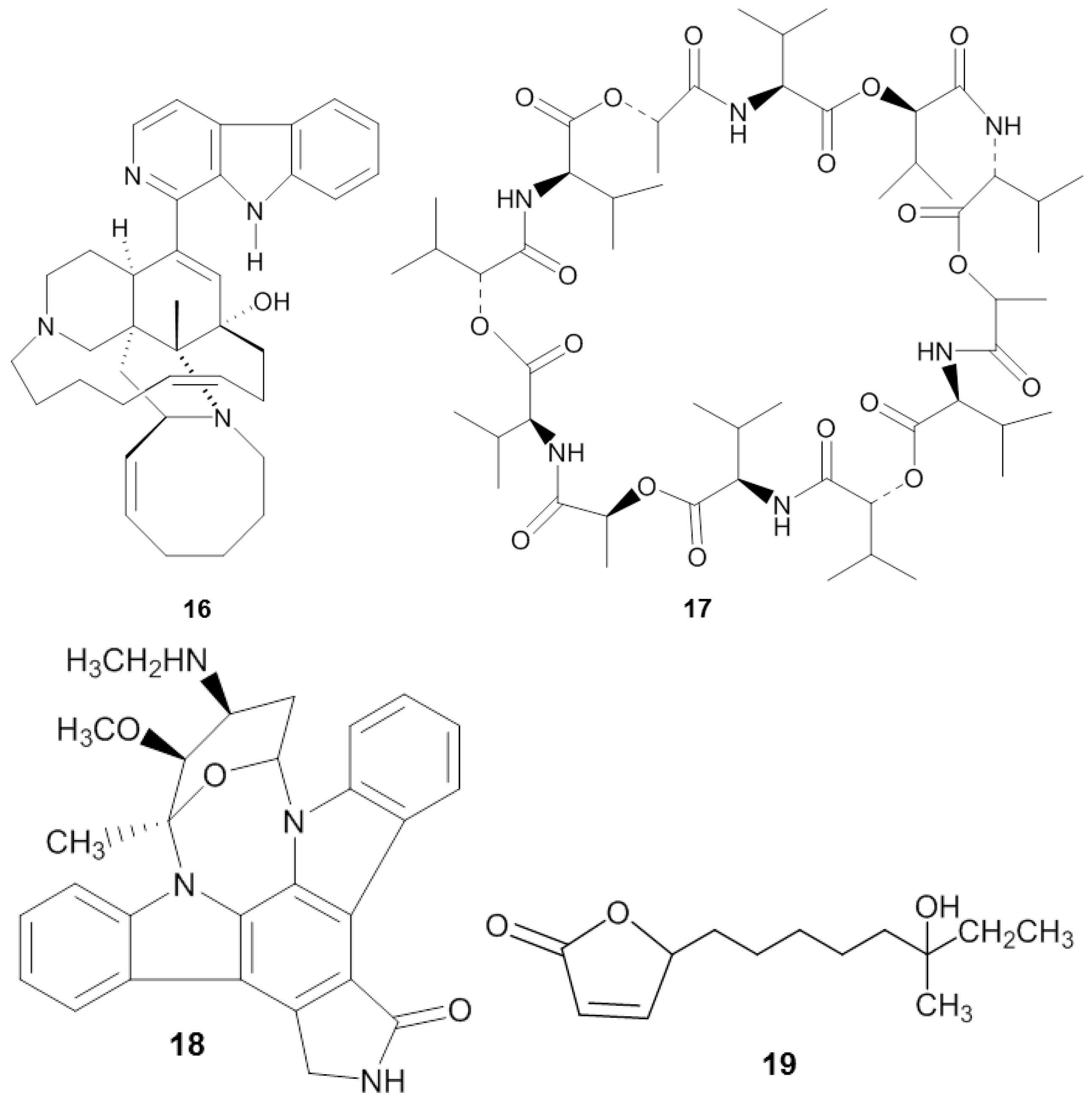

2. Antiviral Compounds

3. Antibacterial Compounds

4. Antifungal Activity

5. Antiprotozoal Activity

6. Dicussion

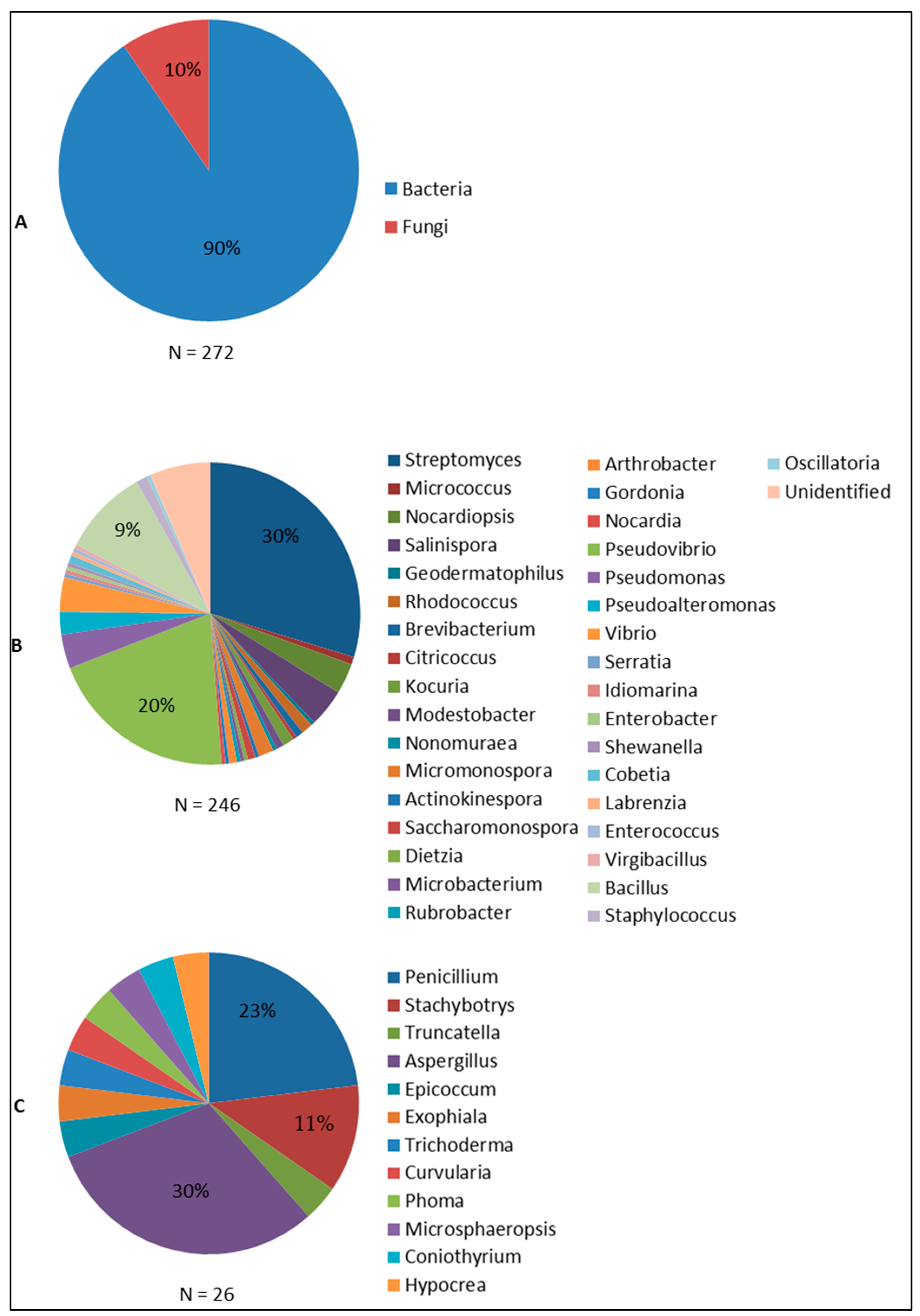

6.1. Antimicrobial Compounds from Sponge-Associated Microbes: What We Learned So Far

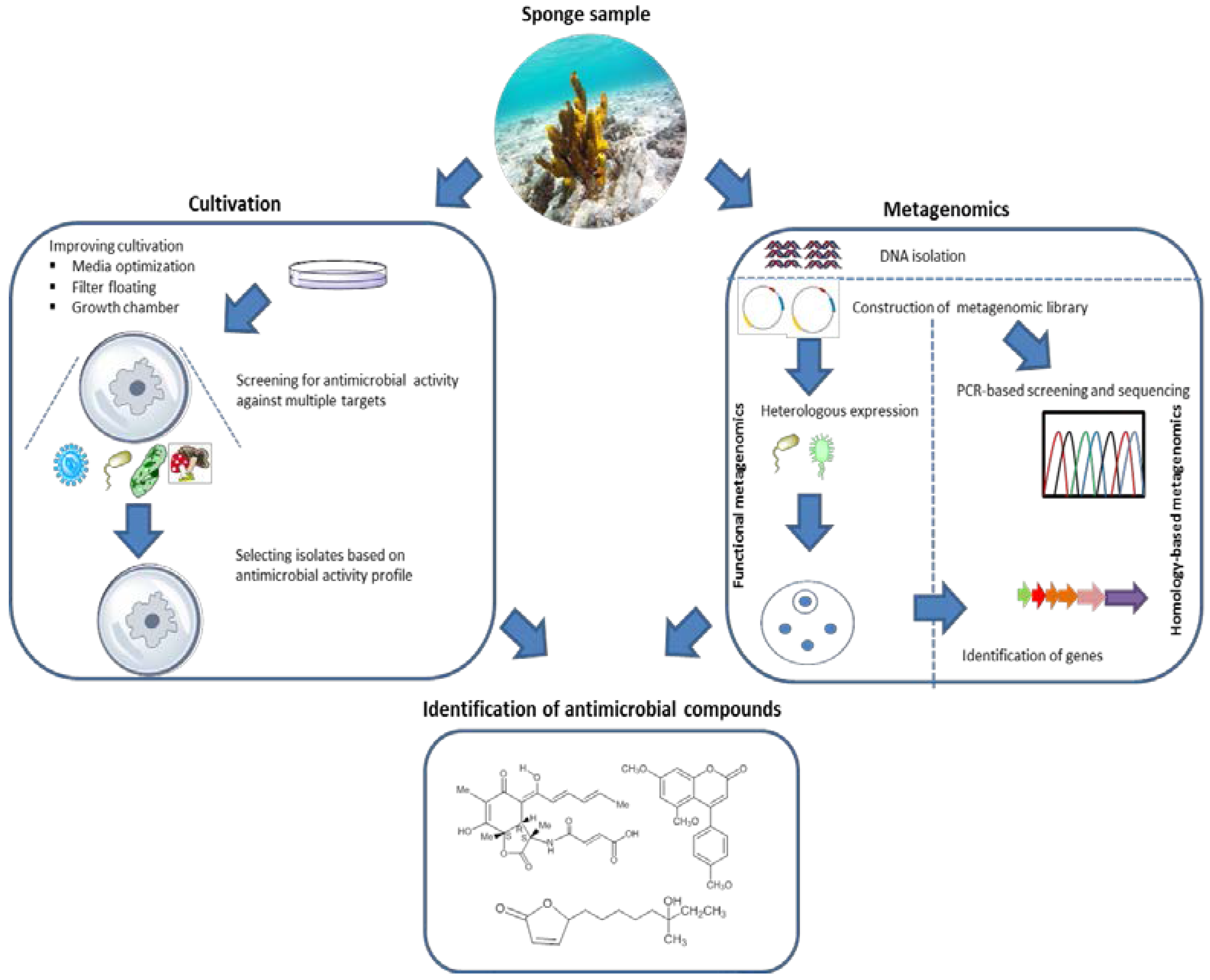

6.2. Discovering Antimicrobial Compounds from Sponge-Associated Microbes: From Culture-Dependent to Culture-Independent Methods

7. Conclusions and Outlook

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: Chaired by Jim O’Neill. 2014. Available online: http://amr-review.org/Publications (accessed on 1 September 2015).

- Antimicrobial Resistance Global Report on Surveillance. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/ (accessed on 1 September 2015).

- Davies, J.; Davies, D. Origins and Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminov, R.I. A brief history of the antibiotic era: Lessons learned and challenges for the future. Front. Microbiol. 2010, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moellering, R.C., Jr. Discovering new antimicrobial agents. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 37, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Projan, S.J. Why is big Pharma getting out of antibacterial drug discovery? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003, 6, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, A. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a Penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzæ. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1929, 10, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.J. The Early History of Antibiotic Discovery: Empiricism Ruled. In Antibiotic Discovery and Development; Dougherty, T.J., Pucci, M.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, D.E.; Brady, S.F.; Bettermann, A.D.; Cianciotto, N.P.; Liles, M.R.; Rondon, M.R.; Clardy, J.; Goodman, R.M.; Handelsman, J. Isolation of Antibiotics Turbomycin A and B from a Metagenomic Library of Soil Microbial DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 4301–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, L.L.; Schneider, T.; Peoples, A.J.; Spoering, A.L.; Engels, I.; Conlon, B.P.; Mueller, A.; Schaberle, T.F.; Hughes, D.E.; Epstein, S.; et al. A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance. Br. Dent. J. 2015, 517, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.L.; Wright, G.D. Novel approaches to discovery of antibacterial agents. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2008, 9, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C.C.; Fenical, W. Antibacterials from the Sea. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 12512–12525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoms, C.; Schupp, P. Biotechnological potential of marine sponges and their associated bacteria as producers of new pharmaceuticals (part II). J. Int. Biotechnol. Law 2005, 2, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, J.A. Diversity and biotechnological potential of microorganisms associated with marine sponges. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2014, 98, 7331–7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.W.; Radax, R.; Steger, D.; Wagner, M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: Evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. R. 2007, 71, 295–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laport, M.S.; Santos, O.C.S.; Muricy, G. Marine Sponges: Potential Sources of New Antimicrobial Drugs. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2009, 10, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, T.R.A.; Kavlekar, D.P.; LokaBharathi, P.A. Marine drugs from sponge-microbe association—A review. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1417–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Gandelman, J.F.; Giambiagi-deMarval, M.; Oelemann, W.M.R.; Laport, M.S. Biotechnological Potential of Sponge-Associated Bacteria. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2014, 15, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graça, A.P.; Viana, F.; Bondoso, J.; Correia, M.I.; Gomes, L.A.G.R.; Humanes, M.; Reis, A.; Xavier, J.; Gaspar, H.; Lage, O. The antimicrobial activity of heterotrophic bacteria isolated from the marine sponge Erylus deficiens (Astrophorida, Geodiidae). Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppers, A.; Stoudenmire, J.; Wu, S.; Lopanik, N.B. Antibiotic activity and microbial community of the temperate sponge, Haliclona sp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 118, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, S.; Kaur, M.; Minneman, K.P. Antiviral Lead Compounds from Marine Sponges. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2619–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, W.; Feeney, R.J. The isolation of a new thymine pentoside from sponges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 2809–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, W.; Feeney, R.J. Contributions to the Study of Marine Products. XXXII. The nucleosides of sponges. I. J. Organ. Chem. 1951, 16, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhara-Bell, J.; Lu, Y. Marine compounds and their antiviral activities. Antiviral Res. 2010, 86, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultel-Poncé, V.; Berge, J.-P.; Debitus, C.; Nicolas, J.-L.; Guyot, M. Metabolites from the sponge-associated bacterium Pseudomonas species. Mar. Biotechnol. 1999, 1, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringmann, G.; Lang, G.; Muhlbacher, J.; Schaumann, K.; Steffens, S.; Rytik, P.G.; Hentschel, U.; Morschhauser, J.; Müller, W.E.G. Sorbicillactone A: A structurally unprecedented bioactive novel-type alkaloid from a sponge-derived fungus. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 2003, 37, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.H.; Lo, L.T.; Zhu, T.J.; Ba, M.Y.; Li, G.Q.; Gu, Q.Q.; Guo, Y.; Li, D.H. Phenylspirodrimanes with Anti-HIV activity from the sponge-derived fungus Stachybotrys chartarum MXH-X73. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 2298–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Cen, S.; Proksch, P.; Lin, W. Isoindolinone-type alkaloids from the sponge-derived fungus Stachybotrys chartarum. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 7010–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Si, L.; Liu, D.; Proksch, P.; Zhou, D.; Lin, W. Truncateols A-N, new isoprenylated cyclohexanols from the sponge-associated fungus Truncatella angustata with anti-H1N1 virus activities. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 2708–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, E.; Rychowska, M.; Szewczyk, B. Antivirals—Current trends in fighting influenza. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2014, 61, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pauletti, P.M.; Cintra, L.S.; Braguine, C.G.; da Silva Filho, A.A.; Silva, M.L.A.E.; Cunha, W.R.; Januário, A.H. Halogenated Indole Alkaloids from Marine Invertebrates. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1526–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, C.S.; Fujimori, D.G.; Walsh, C.T. Halogenation Strategies In Natural Product Biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.X.; Jiao, J.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Gu, Q.Q.; Zhu, T.J.; Li, D.H. Pyronepolyene C-glucosides with NF-kappa B inhibitory and anti-influenza A viral (H1N1) activities from the sponge-associated fungus Epicoccum sp. JJY40. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 3188–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.H.; Zhu, T.J.; Gu, Q.Q.; Xi, R.; Wang, W.; Li, D.H. Structures and antiviral activities of butyrolactone derivatives isolated from Aspergillus terreus MXH-23. J. Ocean Univ. China 2014, 13, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Lin, X.P.; Qin, C.; Liao, S.R.; Wan, J.T.; Zhang, T.Y.; Liu, J.; Fredimoses, M.; Chen, H.; Yang, B.; et al. Antimicrobial and antiviral sesquiterpenoids from sponge-associated fungus, Aspergillus sydowii ZSDS1-F6. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Lin, X.P.; Lu, X.; Wan, J.T.; Zhou, X.F.; Liao, S.R.; Tu, Z.C.; Xu, S.H.; Liu, Y.H. Sesquiterpenoids and xanthones derivatives produced by sponge-derived fungus Stachybotry sp. HH1 ZSDS1F1–2. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, J.C.S.; Kohn, L.K.; Fantinatti-Garboggini, F.; Padilla, M.A.; Flores, E.F.; da Silva, B.P.; de Menezes, C.B.A.; Arns, C.W. Antiviral Activity of Bacillus sp. Isolated from the Marine Sponge Petromica citrina against Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus, a Surrogate Model of the Hepatitis C Virus. Viruses 2013, 5, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inweregbu, K.; Dave, J.; Pittard, A. Nosocomial infections. Cont. Educ. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain 2005, 5, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, R.A.; Gaynes, R.; Edwards, J.R.; System, N.N.I.S. Overview of Nosocomial Infections Caused by Gram-Negative Bacilli. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, K.; Kamigiri, K.; Arao, N.; Suzumura, K.; Kawano, Y.; Yamaoka, M.; Zhang, H.P.; Watanabe, M.; Suzuki, K. YM-266183 and YM-266184, novel thiopeptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus cereus isolated from a marine sponge—I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological properties. J. Antibiot. 2003, 56, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzumura, K.; Yokoi, T.; Funatsu, M.; Nagai, K.; Tanaka, K.; Zhang, H.P.; Suzuki, K. YM-266183 and YM-266184, novel thiopeptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus cereus isolated from a marine sponge—II. Structure elucidation. J. Antibiot. 2003, 56, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomo, S.; Gonzalez, I.; de la Cruz, M.; Martin, J.; Tormo, J.R.; Anderson, M.; Hill, R.T.; Vicente, F.; Reyes, F.; Genilloud, O. Sponge-derived Kocuria and Micrococcus spp. as sources of the new thiazolyl peptide antibiotic kocurin. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, J.; da S. Sousa, T.; Crespo, G.; Palomo, S.; González, I.; Tormo, J.R.; de la Cruz, M.; Anderson, M.; Hill, R.T.; Vicente, F.; et al. Kocurin, the true structure of PM181104, an Anti-Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) thiazolyl peptide from the marine-derived bacterium Kocuria palustris. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneemann, I.; Nagel, K.; Kajahn, I.; Labes, A.; Wiese, J.; Imhoff, J.F. Comprehensive investigation of marine Actinobacteria associated with the sponge Halichondria panicea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 3702–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneemann, I.; Kajahn, I.; Ohlendorf, B.; Zinecker, H.; Erhard, A.; Nagel, K.; Wiese, J.; Imhoff, J.F. Mayamycin, a cytotoxic polyketide from a Streptomyces strain isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria panicea. J. Natl. Prod. 2010, 73, 1309–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimer, A.; Blohm, A.; Quack, T.; Grevelding, C.G.; Kozjak-Pavlovic, V.; Rudel, T.; Hentschel, U.; Abdelmohsen, U.R. Inhibitory activities of the marine streptomycete-derived compound SF2446A2 against Chlamydia trachomatis and Schistosoma mansoni. J. Antibiot. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilevsky, S.; Greub, G.; Nardelli-Haefliger, D.; Baud, D. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: Understanding the Roles of Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Vaccine Research. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 346–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Xu, Y.; Shao, C.-L.; Yang, R.-Y.; Zheng, C.-J.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Fu, X.-M.; Qian, P.-Y.; She, Z.-G.; de Voogd, N.J.; et al. Antibacterial Bisabolane-Type Sesquiterpenoids from the Sponge-Derived Fungus Aspergillus sp. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruksakorn, P.; Arai, M.; Kotoku, N.; Vilchèze, C.; Baughn, A.D.; Moodley, P.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr.; Kobayashi, M. Trichoderins, novel aminolipopeptides from a marine sponge-derived Trichoderma sp., are active against dormant mycobacteria. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 3658–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruksakorn, P.; Arai, M.; Liu, L.; Moodley, P.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr.; Kobayashi, M. Action-Mechanism of Trichoderin A, an Anti-dormant Mycobacterial Aminolipopeptide from Marine Sponge-Derived Trichoderma sp. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.D. Recent findings on the viable but nonculturable state in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, A.R.M.; Hu, Y. Novel approaches to developing new antibiotics for bacterial infections. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 152, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, A.R.M.; Hu, Y. Targeting non-multiplying organisms as a way to develop novel antimicrobials. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008, 29, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltamany, E.E.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Ibrahim, A.K.; Hassanean, H.A.; Hentschel, U.; Ahmed, S.A. New antibacterial xanthone from the marine sponge-derived Micrococcus sp. EG45. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 4939–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayatilake, G.S.; Thornton, M.P.; Leonard, A.C.; Grimwade, J.E.; Baker, B.J. Metabolites from an Antarctic sponge-associated bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Natl. Prod. 1996, 59, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.H.; Ren, B.; Chen, C.X.; Yu, K.; Liu, X.R.; Zhang, Y.H.; Yang, N.; He, H.T.; Liu, X.T.; Dai, H.Q.; et al. Three new sterigmatocystin analogues from marine-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor MF359. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2014, 98, 3753–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramani, R.; Kumar, R.; Prasad, P.; Aalbersberg, W. Cytotoxic and antibacterial substances against multi-drug resistant pathogens from marine sponge symbiont: Citrinin, a secondary metabolite of Penicillium sp. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Li, H.; Hong, J.; Cho, H.; Bae, K.; Kim, M.; Kim, D.-K.; Jung, J. Bioactive metabolites from the sponge-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2010, 33, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Chen, H.; Han, X.; Lin, W.; Yan, X. Antimicrobial screening and active compound isolation from marine bacterium NJ6-3-1 associated with the sponge Hymeniacidon perleve. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, X.; Kang, J.S.; Choi, H.D.; Son, B.W. Chlorohydroaspyrones A and B, Antibacterial Aspyrone Derivatives from the Marine-Derived Fungus Exophiala sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Ouyang, Y.; Zou, K.; Wang, G.; Chen, M.; Sun, H.; Dai, S.; Li, X. Isolation and Difference in Anti-Staphylococcus aureus Bioactivity of Curvularin Derivates from Fungus Eupenicillium sp. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2009, 159, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, O.C.S.; Soares, A.R.; Machado, F.L.S.; Romanos, M.T.V.; Muricy, G.; Giambiagi-deMarval, M.; Laport, M.S. Investigation of biotechnological potential of sponge-associated bacteria collected in Brazilian coast. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 60, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiyanarayanan, G.; Gandhimathi, R.; Sabarathnam, B.; Seghal Kiran, G.; Selvin, J. Optimization and production of pyrrolidone antimicrobial agent from marine sponge-associated Streptomyces sp. MAPS15. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 37, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unson, M.D.; Holland, N.D.; Faulkner, D.J. A brominated secondary metabolite synthesized by the cyanobacterial symbiont of a marine sponge and accumulation of the crystalline metabolite in the sponge tissue. Mar. Biol. 1994, 119, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Aoki, S.; Gato, K.; Matsunami, K.; Kurosu, M.; Kitagawa, I. Marine Natural-Products. XXXIV. Trisindoline, a New Antibiotic Indole Trimer, Produced by a Bacterium of Vibrio sp. Separated from the Marine Sponge Hyrtios-Altum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994, 42, 2449–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, D.; Nazari, T.F.; Kassim, J.; Lim, S.-H. Prodigiosin—An antibacterial red pigment produced by Serratia marcescens IBRL USM 84 associated with a marine sponge Xestospongia testudinaria. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Karuppiah, V.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Feng, G.; Li, Z. Functional gene-based discovery of phenazines from the actinobacteria associated with marine sponges in the South China Sea. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabel, C.T.; Vater, J.; Wilde, C.; Franke, P.; Hofemeister, J.; Adler, B.; Bringmann, G.; Hacker, J.; Hentschel, U. Antimicrobial activities and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of Bacillus isolates from the marine sponge Aplysina aerophoba. Mar. Biotechnol. 2003, 5, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, P.; Wahidullah, S.; Rodrigues, C.; Souza, L.D. The Sponge-associated Bacterium Bacillus licheniformis SAB1: A Source of Antimicrobial Compounds. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadulco, R.; Brauers, G.; Edrada, R.A.; Ebel, R.; Wray, V.; Proksch, P. New Metabolites from Sponge-Derived Fungi Curvularia lunata and Cladosporium herbarum II. J. Natl. Prod. 2002, 65, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, R.W.; Barret, M.; Cotter, P.D.; O’Connor, P.M.; Chen, R.; Morrissey, J.P.; Dobson, A.D.W.; O’Gara, F.; Barbosa, T.M. Subtilomycin: A New Lantibiotic from Bacillus subtilis Strain MMA7 Isolated from the Marine Sponge Haliclona simulans. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1878–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, C.; Reen, F.; Mooij, M.; Stewart, F.; Chabot, J.-B.; Guerra, A.; Glöckner, F.; Nielsen, K.; Gram, L.; Dobson, A.; et al. Characterisation of Non-Autoinducing Tropodithietic Acid (TDA) Production from Marine Sponge Pseudovibrio Species. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5960–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvin, J. Exploring the Antagonistic Producer Streptomyces MSI051: Implications of Polyketide Synthase Gene Type II and a Ubiquitous Defense Enzyme Phospholipase A2 in the Host Sponge Dendrilla nigra. Curr. Microbiol. 2009, 58, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Yan, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Lin, W. Hymeniacidon perleve associated bioactive bacterium Pseudomonas sp. NJ6–3-1. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2005, 41, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenupriya, J.; Thangaraj, M. Isolation and molecular characterization of bioactive secondary metabolites from Callyspongia spp. associated fungi. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2010, 3, 738–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Santos-Gandelman, J.; Hardoim, C.P.; George, I.; Cornelis, P.; Laport, M. Antibacterial activity and mutagenesis of sponge-associated Pseudomonas fluorescens H41. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2015, 108, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, O.C.S.; Pontes, P.V.M.L.; Santos, J.F.M.; Muricy, G.; Giambiagi-deMarval, M.; Laport, M.S. Isolation, characterization and phylogeny of sponge-associated bacteria with antimicrobial activities from Brazil. Res. Microbiol. 2010, 161, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’ Halloran, J.A.; Barbosa, T.M.; Morrissey, J.P.; Kennedy, J.; O’ Gara, F.; Dobson, A.D.W. Diversity and antimicrobial activity of Pseudovibrio spp. from Irish marine sponges. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 1495–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.K.; Garson, M.J.; Fuerst, J.A. Marine actinomycetes related to the “Salinospora“ group from the Great Barrier Reef sponge Pseudoceratina clavata. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvin, J.; Joseph, S.; Asha, K.R.T.; Manjusha, W.A.; Sangeetha, V.S.; Jayaseema, D.M.; Antony, M.C.; Vinitha, A.J.D. Antibacterial potential of antagonistic Streptomyces sp. isolated from marine sponge Dendrilla nigra. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 50, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, P.; Wang, D.-X.; Ding, S.-X.; Zhao, J. Isolation and diversity of natural product biosynthetic genes of cultivable bacteria associated with marine sponge Mycale sp. from the coast of Fujian, China. Can. J. Microbiol. 2014, 60, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Pimentel-Elardo, S.M.; Hanora, A.; Radwan, M.; Abou-El-Ela, S.H.; Ahmed, S.; Hentschel, U. Isolation, Phylogenetic Analysis and Anti-infective Activity Screening of Marine Sponge-Associated Actinomycetes. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemer, B.; Kennedy, J.; Margassery, L.M.; Morrissey, J.P.; O’Gara, F.; Dobson, A.D.W. Diversity and antimicrobial activities of microbes from two Irish marine sponges, Suberites carnosus and Leucosolenia sp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 112, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentschel, U.; Schmid, M.; Wagner, M.; Fieseler, L.; Gernert, C.; Hacker, J. Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of bacteria with antimicrobial activities from the Mediterranean sponges Aplysina aerophoba and Aplysina cavernicola. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2001, 35, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopi, M.; Kumaran, S.; Kumar, T.T.A.; Deivasigamani, B.; Alagappan, K.; Prasad, S.G. Antibacterial potential of sponge endosymbiont marine Enterobacter sp. at Kavaratti Island, Lakshadweep archipelago. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2012, 5, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelossi, E.; Milanese, M.; Milano, A.; Pronzato, R.; Riccardi, G. Characterisation and antimicrobial activity of epibiotic bacteria from Petrosia ficiformis (Porifera, Demospongiae). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2004, 309, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skariyachan, S.; Rao, A.G.; Patil, M.R.; Saikia, B.; Bharadwaj Kn, V.; Rao Gs, J. Antimicrobial potential of metabolites extracted from bacterial symbionts associated with marine sponges in coastal area of Gulf of Mannar Biosphere, India. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 58, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.; Baker, P.; Piper, C.; Cotter, P.; Walsh, M.; Mooij, M.; Bourke, M.; Rea, M.; O’Connor, P.; Ross, R.P.; et al. Isolation and Analysis of Bacteria with Antimicrobial Activities from the Marine Sponge Haliclona simulans Collected from Irish Waters. Mar. Biotechnol. 2009, 11, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, A.L.; Labes, A.; Wiese, J.; Bruhn, T.; Bringmann, G.; Imhoff, J.F. Nature’s Lab for Derivatization: New and Revised Structures of a Variety of Streptophenazines Produced by a Sponge-Derived Streptomyces Strain. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1699–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scopel, M.; Abraham, W.-R.; Henriques, A.T.; Macedo, A.J. Dipeptide cis-cyclo(Leucyl-Tyrosyl) produced by sponge associated Penicillium sp. F37 inhibits biofilm formation of the pathogenic Staphylococcus epidermidis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manilal, A.; Sabarathnam, B.; Kiran, G.S.; Sujith, S.; Shakir, C.; Selvin, J. Antagonistic Potentials of Marine Sponge Associated Fungi Aspergillus clavatus MFD15. Asian J. Med. Sci. 2010, 2, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhimathi, R.; Arunkumar, M.; Selvin, J.; Thangavelu, T.; Sivaramakrishnan, S.; Kiran, G.S.; Shanmughapriya, S.; Natarajaseenivasan, K. Antimicrobial potential of sponge associated marine actinomycetes. J. Med. Mycol. 2008, 18, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvin, J.; Shanmughapriya, S.; Gandhimathi, R.; Seghal Kiran, G.; Rajeetha Ravji, T.; Natarajaseenivasan, K.; Hema, T.A. Optimization and production of novel antimicrobial agents from sponge associated marine actinomycetes Nocardiopsis dassonvillei MAD08. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 83, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.J.; Kwon, H.C.; Ham, J.; Yang, H.O. 6-Hydroxymethyl-1-phenazine-carboxamide and 1,6-phenazinedimethanol from a marine bacterium, Brevibacterium sp. KMD 003, associated with marine purple vase sponge. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viegelmann, C.; Margassery, L.M.; Kennedy, J.; Zhang, T.; O’Brien, C.; O’Gara, F.; Morrissey, J.P.; Dobson, A.D.W.; Edrada-Ebel, R. Metabolomic Profiling and Genomic Study of a Marine Sponge-Associated Streptomyces sp. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 3323–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, T.P.; Bhat, A.W.; Shouche, Y.S.; Roy, U.; Siddharth, J.; Sarma, S.P. Antimicrobial activity of marine bacteria associated with sponges from the waters off the coast of South East India. Microbiol. Res. 2006, 161, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margassery, L.M.; Kennedy, J.; O’Gara, F.; Dobson, A.D.; Morrissey, J.P. Diversity and antibacterial activity of bacteria isolated from the coastal marine sponges Amphilectus fucorum and Eurypon major. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 55, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashti, Y.; Grkovic, T.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Hentschel, U.; Quinn, R.J. Production of Induced Secondary Metabolites by a Co-Culture of Sponge-Associated Actinomycetes, Actinokineospora sp. EG49 and Nocardiopsis sp. RV163. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 3046–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachanamol, R.S.; Lipton, A.P.; Thankamani, V.; Sarika, A.R.; Selvin, J. Molecular characterization and bioactivity profile of the tropical sponge-associated bacterium Shewanella algae VCDB. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2014, 68, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, S.; Carre-Mlouka, A.; Domart-Coulon, I.; Vacelet, J.; Bourguet-Kondracki, M.-L. Exploring cultivable Bacteria from the prokaryotic community associated with the carnivorous sponge Asbestopluma hypogea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 88, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, S.; Carré-Mlouka, A.; Descarrega, F.; Ereskovsky, A.; Longeon, A.; Mouray, E.; Florent, I.; Bourguet-Kondracki, M.L. Diversity and biological activities of the bacterial community associated with the marine sponge Phorbas tenacior (Porifera, Demospongiae). Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 58, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkowska-Kuleta, J.; Rapala-Kozik, M.; Kozik, A. Fungi pathogenic to humans: Molecular bases of virulence of Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2009, 56, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Thiel, D.H.; George, M.; Moore, C.M. Fungal Infections: Their Diagnosis and Treatment in Transplant Recipients. Int. J. Hepatol. 2012, 2012, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, M.D. Changing patterns and trends in systemic fungal infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemoth. 2005, 56, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidel, P.L.; Vazquez, J.A.; Sobel, J.D. Candida glabrata: Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Disease with Comparison to C. albicans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galimberti, R.; Torre, A.C.; Baztán, M.C.; Rodriguez-Chiappetta, F. Emerging systemic fungal infections. Clin. Dermatol. 2012, 30, 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gendy, M.A.; El-Bondkly, A.A. Production and genetic improvement of a novel antimycotic agent, Saadamycin, against Dermatophytes and other clinical fungi from Endophytic Streptomyces sp. Hedaya48. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 37, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, K.; Kamigiri, K.; Matsumoto, H.; Kawano, Y.; Yamaoka, M.; Shimoi, H.; Watanabe, M.; Suzuki, K. YM-202204, a new antifungal antibiotic produced by marine fungus Phoma sp. J. Antibiot. 2002, 55, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLellan, C.A.; Whitesell, L.; King, O.D.; Lancaster, A.K.; Mazitschek, R.; Lindquist, S. Inhibiting GPI Anchor Biosynthesis in Fungi Stresses the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Enhances Immunogenicity. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butts, A.; Krysan, D.J. Antifungal Drug Discovery: Something Old and Something New. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edrada, R.A.; Heubes, M.; Brauers, G.; Wray, V.; Berg, A.; Grafe, U.; Wohlfarth, M.; Muhlbacher, J.; Schaumann, K.; Sudarsono, S.; et al. Online analysis of xestodecalactones A–C, novel bioactive metabolites from the fungus Penicillium cf. montanense and their subsequent isolation from the sponge Xestospongia exigua. J. Natl. Prod. 2002, 65, 1598–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, N.; Nishijima, M.; Adachi, K.; Sano, H. Novel Antimycin Antibiotics, Urauchimycin-a and Urauchimycin-B, Produced by Marine Actinomycete. J. Antibiot. 1993, 46, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.T.; Takagi, M.; Shin-ya, K. Diversity, Salt Requirement, and Antibiotic Production of Actinobacteria Isolated from Marine Sponges. Actinomycetologica 2010, 24, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Koch, L.; Thu, K.M.; Rahamim, Y.; Aluma, Y.; Ilan, M.; Yarden, O.; Carmeli, S. Novel terpenoids of the fungus Aspergillus insuetus isolated from the Mediterranean sponge Psammocinia sp. collected along the coast of Israel. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 6587–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holler, U.; Konig, G.M.; Wright, A.D. Three new metabolites from marine-derived fungi of the genera Coniothyrium and Microsphaeropsis. J. Natl. Prod. 1999, 62, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, K.K.H.; Holmes, M.J.; Higa, T.; Hamann, M.T.; Kara, U.A.K. In vivo antimalarial activity of the beta-carboline alkaloid manzamine A. Antimicrob. Agents Chim. 2000, 44, 1645–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipkema, D.; Franssen, M.C.R.; Osinga, R.; Tramper, J.; Wijffels, R.H. Marine sponges as pharmacy. Mar. Biotechnol. 2005, 7, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattorusso, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Marine Antimalarials. Mar. Drugs 2009, 7, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, R.; Higa, T.; Jefford, C.W.; Bernardinelli, G. Manzamine A, a novel antitumor alkaloid from a sponge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 6404–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, M.; Hanora, A.; Khalifa, S.; Abou-El-Ela, S.H. Manzamines. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 1765–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyase, F.L.; Akala, H.M.; Johnson, J.D.; Walsh, D.S. Inhibitory Activity of Ferroquine, versus Chloroquine, against Western Kenya Plasmodium falciparum Field Isolates Determined by a SYBR Green I in Vitro Assay. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 85, 984–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, K.V.; Santarsiero, B.D.; Mesecar, A.D.; Schinazi, R.F.; Tekwani, B.L.; Hamann, M.T. New manzamine alkaloids with activity against infectious and tropical parasitic diseases from an Indonesian sponge. J. Natl. Prod. 2003, 66, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Chen, Y.-J.; Aoki, S.; In, Y.; Ishida, T.; Kitagawa, I. Four new β-carboline alkaloids isolated from two Okinawan marine sponges of Xestospongia sp. and Haliclona sp. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 3727–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.V.; Kasanah, N.; Wahyuono, S.U.; Tekwani, B.L.; Schinazi, R.F.; Hamann, M.T. Three new manzamine alkaloids from a common Indonesian sponge and their activity against infectious and tropical parasitic diseases. J. Natl. Prod. 2004, 67, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, R.T.; Hamann, M.; Peraud, O.T.; Kasanah, N. Manzamine Producing Actinomycetes. U.S. Patent 20050244938 A1, 3 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Peraud, O. Isolation and Characterization of a Sponge-Associated Actinomycete that Produces Manzamines. University of Maryland, 2006. Available online: http://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/4114 (accessed on 1 September 2015).

- Waters, A.L.; Peraud, O.; Kasanah, N.; Sims, J.; Kothalawala, N.; Anderson, M.A.; Abbas, S.H.; Rao, K.V.; Jupally, V.R.; Kelly, M.; et al. An analysis of the sponge Acanthostrongylophora igens’ microbiome yields an actinomycete that produces the natural product manzamine A. Front. Mar. Sci. 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel-Elardo, S.M.; Kozytska, S.; Bugni, T.S.; Ireland, C.M.; Moll, H.; Hentschel, U. Anti-Parasitic Compounds from Streptomyces sp. Strains Isolated from Mediterranean Sponges. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scopel, M.; dos Santos, O.; Frasson, A.P.; Abraham, W.-R.; Tasca, T.; Henriques, A.T.; Macedo, A.J. Anti-Trichomonas vaginalis activity of marine-associated fungi from the South Brazilian Coast. Exp. Parasitol. 2013, 133, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrin, D.; Delgaty, K.; Bhatt, R.; Garber, G. Clinical and microbiological aspects of Trichomonas vaginalis. Clin. Microbiol Rev. 1998, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inbaneson, S.J.; Ravikumar, S. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of marine sponge Hyattella intestinalis associated bacteria against Plasmodium falciparum. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2011, 1, S100–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbaneson, S.J.; Ravikumar, S. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of marine sponge Stylissa carteri associated bacteria against Plasmodium falciparum. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2012, 2, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbaneson, S.J.; Ravikumar, S. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of marine sponge Clathria indica associated bacteria against Plasmodium falciparum. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S1090–S1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbaneson, S.J.; Ravikumar, S. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of Clathria vulpina sponge associated bacteria against Plasmodium falciparum. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2012, 2, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbaneson, S.J.; Ravikumar, S. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of bacterium RJAUTHB 14 associated with marine sponge Haliclona Grant against Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 110, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Szesny, M.; Othman, E.M.; Schirmeister, T.; Grond, S.; Stopper, H.; Hentschel, U. Antioxidant and Anti-Protease Activities of Diazepinomicin from the Sponge-Associated Micromonospora Strain RV115. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 2208–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Cheng, C.; Viegelmann, C.; Zhang, T.; Grkovic, T.; Ahmed, S.; Quinn, R.J.; Hentschel, U.; Edrada-Ebel, R. Dereplication Strategies for Targeted Isolation of New Antitrypanosomal Actinosporins A and B from a Marine Sponge Associated-Actinokineospora sp. EG49. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1220–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; MacIntyre, L.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Horn, H.; Polymenakou, P.N.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Hentschel, U. Biodiversity, Anti-Trypanosomal Activity Screening, and Metabolomic Profiling of Actinomycetes Isolated from Mediterranean Sponges. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel-Elardo, S.M.; Buback, V.; Gulder, T.A.M.; Bugni, T.S.; Reppart, J.; Bringmann, G.; Ireland, C.M.; Schirmeister, T.; Hentschel, U. New Tetromycin Derivatives with Anti-Trypanosomal and Protease Inhibitory Activities. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 1682–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashforth, E.J.; Fu, C.Z.; Liu, X.Y.; Dai, H.Q.; Song, F.H.; Guo, H.; Zhang, L.X. Bioprospecting for antituberculosis leads from microbial metabolites. Natl. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seipke, R.F.; Kaltenpoth, M.; Hutchings, M.I. Streptomyces as symbionts: An emerging and widespread theme? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 862–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traxler, M.F.; Kolter, R. Natural products in soil microbe interactions and evolution. Natl. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, N.P.; Turner, G.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal secondary metabolism—From biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microb. 2005, 3, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, J.B.; Nielsen, J. Phenazine Natural Products: Biosynthesis, Synthetic Analogues, and Biological Activity. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1663–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Préville, P.; Morin, N.; Mounir, S.; Cai, W.; Siddiqui, M.A. Hepatitis C viral IRES inhibition by phenazine and phenazine-like molecules. Bioorg. Med.Chem. Lett. 2000, 10, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrodi, D.V.; Mavrodi, O.V.; Parejko, J.A.; Bonsall, R.F.; Kwak, Y.S.; Paulitz, T.C.; Thomashow, L.S.; Weller, D.M. Accumulation of the Antibiotic Phenazine-1-Carboxylic Acid in the Rhizosphere of Dryland Cereals. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2012, 78, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makgatho, M.E.; Anderson, R.; O’Sullivan, J.F.; Egan, T.J.; Freese, J.A.; Cornelius, N.; van Rensburg, C.E.J. Tetramethylpiperidine-substituted phenazines as novel anti-plasmodial agents. Drug Dev. Res. 2000, 50, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lu, J.; Bao, W.; Wang, Y.; Xi, T. A novel anticancer and antifungus phenazine derivative from a marine actinomycete BM-17. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 167, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentschel, U.; Piel, J.; Degnan, S.M.; Taylor, M.W. Genomic insights into the marine sponge microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 641–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schippers, K.J.; Sipkema, D.; Osinga, R.; Smidt, H.; Pomponi, S.A.; Martens, D.E.; Wijffels, R.H. Cultivation of sponges, sponge cells and symbionts: Achievements and future prospects. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2012, 62, 273–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, B.; de Jaeger, L.; Smidt, H.; Sipkema, D. Culture-dependent and independent approaches for identifying novel halogenases encoded by Crambe crambe (marine sponge) microbiota. Sci. Rep. UK 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipkema, D.; Schippers, K.; Maalcke, W.J.; Yang, Y.; Salim, S.; Blanch, H.W. Multiple Approaches To Enhance the Cultivability of Bacteria Associated with the Marine Sponge Haliclona (gellius) sp. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2011, 77, 2130–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, W.E.G.; Zahn, R.K.; Kurelec, B.; Lucu, C.; Muller, I.; Uhlenbruck, G. Lectin, a Possible Basis for Symbiosis between Bacteria and Sponges. J. Bacteriol. 1981, 145, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steinert, G.; Whitfield, S.; Taylor, M.; Thoms, C.; Schupp, P. Application of Diffusion Growth Chambers for the Cultivation of Marine Sponge-Associated Bacteria. Mar. Biotechnol. 2014, 16, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Blasiak, L.C.; Karolin, J.O.; Powell, R.J.; Geddes, C.D.; Hill, R.T. Phosphorus sequestration in the form of polyphosphate by microbial symbionts in marine sponges. Proc. Natl. Acad.Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4381–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unson, M.D.; Faulkner, D.J. Cyanobacterial Symbiont Biosynthesis of Chlorinated Metabolites from Dysidea-Herbacea (Porifera). Experientia 1993, 49, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milshteyn, A.; Schneider, J.S.; Brady, S.F. Mining the Metabiome: Identifying Novel Natural Products from Microbial Communities. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmann, A.; Aly, A.; Lin, W.; Wang, B.; Proksch, P. Co-Cultivation—A Powerful Emerging Tool for Enhancing the Chemical Diversity of Microorganisms. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, S.; Bohni, N.; Schnee, S.; Schumpp, O.; Gindro, K.; Wolfender, J.-L. Metabolite induction via microorganism co-culture: A potential way to enhance chemical diversity for drug discovery. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1180–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.-Y.-S.; Graziani, E.; Waters, B.; Pan, W.; Li, X.; McDermott, J.; Meurer, G.; Saxena, G.; Andersen, R.J.; Davies, J. Novel Natural Products from Soil DNA Libraries in a Streptomycete Host. Organ. Lett. 2000, 2, 2401–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.F.; Chao, C.J.; Handelsman, J.; Clardy, J. Cloning and heterologous expression of a natural product biosynthetic gene cluster from eDNA. Organ. Lett. 2001, 3, 1981–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.J.; Lim, H.K.; Kim, J.C.; Choi, G.J.; Park, E.J.; Lee, M.H.; Chung, Y.R.; Lee, S.W. Forest soil metagenome gene cluster involved in antifungal activity expression in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2008, 74, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, C.; Daniel, R. Metagenomic Analyses: Past and Future Trends. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2011, 77, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.C.; Piel, J. Metagenomic Approaches for Exploiting Uncultivated Bacteria as a Resource for Novel Biosynthetic Enzymology. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, J. Approaches to Capturing and Designing Biologically Active Small Molecules Produced by Uncultured Microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 65, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeil, I.A.; Tiong, C.L.; Minor, C.; August, P.R.; Grossman, T.H.; Loiacono, K.A.; Lynch, B.A.; Phillips, T.; Narula, S.; Sundaramoorthi, R.; et al. Expression and isolation of antimicrobial small molecules from soil DNA libraries. J. Mol. Microb. Biotech. 2001, 3, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, P.Y.; Burke, C.; Lewis, M.; Kjelleberg, S.; Thomas, T. Novel Antibacterial Proteins from the Microbial Communities Associated with the Sponge Cymbastela concentrica and the Green Alga Ulva australis. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2011, 77, 1512–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Wakimoto, T.; Egami, Y.; Kenmoku, H.; Ito, T.; Asakawa, Y.; Abe, I. Heterologously expressed β-hydroxyl fatty acids from a metagenomic library of a marine sponge. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 7322–7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Wang, B.C.; Wakimoto, T.; Wang, M.Y.; Zhu, L.C.; Abe, I. Cyclodipeptides from Metagenomic Library of a Japanese Marine Sponge. J. Brazil. Chem. Soc. 2013, 24, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongley, S.E.; Bian, X.Y.; Neilan, B.A.; Muller, R. Recent advances in the heterologous expression of microbial natural product biosynthetic pathways. Natl. Prod. Rep. 2013, 30, 1121–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltz, R.H. Molecular engineering approaches to peptide, polyketide and other antibiotics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, A.W.; Jackson, S.; Kennedy, J.; Margassery, L.; Flemer, B.; O’Leary, N.; Morrissey, J.; O’Gara, F. Marine Sponges—Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. In Springer Handbook of Marine Biotechnology; Kim, S.-K., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 219–254. [Google Scholar]

- Baltz, R.H. Streptomyces and Saccharopolyspora hosts for heterologous expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biot. 2010, 37, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.; Marchesi, J.R.; Dobson, A.D.W. Metagenomic approaches to exploit the biotechnological potential of the microbial consortia of marine sponges. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 75, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, J. A polyketide synthase-peptide synthetase gene cluster from an uncultured bacterial symbiont of Paederus beetles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14002–14007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, J.; Hui, D.; Wen, G.; Butzke, D.; Platzer, M.; Fusetani, N.; Matsunaga, S. Antitumor polyketide biosynthesis by an uncultivated bacterial symbiont of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 16222–16227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, J.; Hui, D.Q.; Fusetani, N.; Matsunaga, S. Targeting modular polyketide synthases with iteratively acting acyltransferases from metagenomes of uncultured bacterial consortia. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, J.; Wen, G.; Platzer, M.; Hui, D. Unprecedented Diversity of Catalytic Domains in the First Four Modules of the Putative Pederin Polyketide Synthase. ChemBioChem. 2004, 5, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, J.; Butzke, D.; Fusetani, N.; Hui, D.; Platzer, M.; Wen, G.; Matsunaga, S. Exploring the Chemistry of Uncultivated Bacterial Symbionts: Antitumor Polyketides of the Pederin Family. J. Natl. Prod. 2005, 68, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisch, K.M.; Gurgui, C.; Heycke, N.; van der Sar, S.A.; Anderson, S.A.; Webb, V.L.; Taudien, S.; Platzer, M.; Rubio, B.K.; Robinson, S.J.; et al. Polyketide assembly lines of uncultivated sponge symbionts from structure-based gene targeting. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirmer, A.; Gadkari, R.; Reeves, C.D.; Ibrahim, F.; DeLong, E.F.; Hutchinson, C.R. Metagenomic analysis reveals diverse polyketide synthase gene clusters in microorganisms associated with the marine sponge Discodermia dissoluta. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2005, 71, 4840–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoads, A.; Au, K.F. PacBio Sequencing and Its Applications. Genomics Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alt, S.; Wilkinson, B. Biosynthesis of the Novel Macrolide Antibiotic Anthracimycin. Acs Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 2468–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podar, M.; Abulencia, C.B.; Walcher, M.; Hutchison, D.; Zengler, K.; Garcia, J.A.; Holland, T.; Cotton, D.; Hauser, L.; Keller, M. Targeted access to the genomes of low-abundance organisms in complex microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2007, 73, 3205–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.C.; Mori, T.; Ruckert, C.; Uria, A.R.; Helf, M.J.; Takada, K.; Gernert, C.; Steffens, U.A.E.; Heycke, N.; Schmitt, S.; et al. An environmental bacterial taxon with a large and distinct metabolic repertoire. Nature 2014, 506, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik, J.J.; Brady, S.F. Recent application of metagenomic approaches toward the discovery of antimicrobials and other bioactive small molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010, 13, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medema, M.H.; Blin, K.; Cimermancic, P.; de Jager, V.; Zakrzewski, P.; Fischbach, M.A.; Weber, T.; Takano, E.; Breitling, R. antiSMASH: Rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W339–W346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, J.; Ryu, S. Screening for novel enzymes from metagenome and SIGEX, as a way to improve it. Microb. Cell Fact. 2005, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sponge | Origin (Depth) | Microorganism | Phylum | Compound | Property | Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homophymia sp. | Touho, New Caledonia (ND) | Pseudomonas sp. 1531-E7 | Proteobacteria | 2-undecyl-4-quinolone | IC50 (10−3 µg/mL) | HIV-1 | [25] |

| Ircinia fasciculata | Bight of Fetovaia, Italy (17.5 m) | Penicillium chrysogenum | Ascomycota | Sorbicillactone A | Reducing protein expression and activity of reverse transcriptase (0.3–1 µg/mL) | HIV-1 | [26] |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys chartarum MXH-X73 | Ascomycota | Stachybotrin D | EC50 (3.71 µg/mL) | HIV-1 | [27] |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys chartarum MXH-X73 | Ascomycota | Stachybotrin D | EC50 (3.09 µg/mL) | Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) resistant HIV-1 strain 1RT-K103N | [27] |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys chartarum MXH-X73 | Ascomycota | Stachybotrin D | EC50 (10.51 µg/mL) | NNRTI resistant HIV-1RT-L100I, K103N | [27] |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys chartarum MXH-X73 | Ascomycota | Stachybotrin D | EC50 (5.87 µg/mL) | NNRTI resistant HIV-1RT-K103N, V108I | [27] |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys chartarum MXH-X73 | Ascomycota | Stachybotrin D | EC50 (6.27 µg/mL) | NNRTI resistant HIV-1RT-K103N, G190A | [27] |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys chartarum MXH-X73 | Ascomycota | Stachybotrin D | EC50 (2.73 µg/mL) | NNRTI resistant HIV-1RT-K103N, P225H | [27] |

| Niphates sp. | Beibuwan Bay, China (10 m) | Stachybotrys chartarum | Ascomycota | Chartarutine B | IC50 (1.81 µg/mL) | HIV-1 | [28] |

| Niphates sp. | Beibuwan Bay, China (10 m) | Stachybotrys chartarum | Ascomycota | Chartarutine G | IC50 (2.05 µg/mL) | HIV-1 | [28] |

| Niphates sp. | Beibuwan Bay, China (10 m) | Stachybotrys chartarum | Ascomycota | Chartarutine H | IC50 (2.05 µg/mL) | HIV-1 | [28] |

| Amphimedon sp. | Yongxin island, China (10 m) | Truncatella angustata | Ascomycota | Truncateol M | IC50 (2.91 µg/mL) | H1N1 | [29] |

| Callyspongia sp. | Sanya, China (ND) | Epicoccum sp. JJY40 | Ascomycota | Pyronepolyene C-glucoside iso-D8646-2-6 | IC50 (56.06 µg/mL) | H1N1 | [33] |

| Callyspongia sp. | Sanya, China (ND) | Epicoccum sp. JJY40 | Ascomycota | Pyronepolyene C-glucoside, 8646-2-6 | IC50 (62.07 µg/mL) | H1N1 | [33] |

| Unidentified | Naozhou Sea, China (ND) | Aspergillus terreus MXH-23 | Ascomycota | Butyrolactone III | Percentage of inhibition (53.9% ± 0.53% at 50 µg/L) | H1N1 | [34] |

| Unidentified | Naozhou Sea, China (ND) | Aspergillus terreus MXH-23 | Ascomycota | 5-[(3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-1-benzopyran-6-yl)-methyl]-3-hydroxy-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2(5H)-furanone | Percentage of inhibition (57.8% ± 1.99% at 50 µg/L) | H1N1 | [34] |

| Unidentified | Paracel Islands (ND) | Aspergillus sydowii ZSDS1-F6 | Ascomycota | (Z)-5-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-(60)-methylhept-20-en-20-yl)-phenol | IC50 (14.30 µg/mL) | H3N2 | [35] |

| Unidentified | Paracel Islands (ND) | Aspergillus sydowii ZSDS1-F6 | Ascomycota | Diorcinol | IC50 (15.31 µg/mL) | H3N2 | [35] |

| Unidentified | Paracel slands (ND) | Aspergillus sydowii ZSDS1-F6 | Ascomycota | Cordyol C | IC50 (19.33 µg/mL) | H3N2 | [35] |

| Unidentified | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys sp. HH1 ZSDS1F1-2 | Ascomycota | Stachybogrisephenone B | IC50 (10.2 µg/mL) | Enterovirus 71 (EV71) | [36] |

| Unidentified | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys sp. HH1 ZSDS1F1-2 | Ascomycota | Grisephenone A | IC50 (16.94 µg/mL | Enterovirus 71 (EV71) | [36] |

| Unidentified | Paracel Islands (ND) | Stachybotrys sp. HH1 ZSDS1F1-2 | Ascomycota | 3,6,8-Trihydroxy-1-methylxanthone | IC50 (10.4 µg/mL) | Enterovirus 71 (EV71) | [36] |

| Petromica citrina | Saco do Poço, Brazil (5–15 m) | Bacillus sp. B555 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | IC50 (27.35 μg/mL) EC50 (>500 μg/mL) | Bovine viral diarrhea virus | [37] |

| Petromica citrina | Saco do Poço, Brazil (5–15 m) | Bacillus sp. B584 | Firmcutes | Unidentified | IC50 (10.24 μg/mL) EC50 (277 μg/mL) | Bovine viral diarrhea virus | [37] |

| Petromica citrina | Saco do Poço, Brazil (5–15 m) | Bacillus sp. B616 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | IC50 (47 μg/mL) EC50 (1500 μg/mL) | Bovine viral diarrhea virus | [37] |

| Sponge | Origin (Depth) | Microorganism | Phylum | Compound | Property | Target | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halichondria japonica | Iriomote island, Japan (ND) | Bacillus cereus QNO3323 | Firmicutes | Thiopeptide YM-266183 | MIC (0.025 µg/mL) | Staphylococcus aureus | [40,41] | |

| Halichondria japonica | Iriomote island, Japan (ND) | Bacillus cereus QNO3323 | Firmicutes | Thiopeptide YM-266184 | MIC (0.025 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [40,41] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Kiel Fjord, Baltic Sea, Germany (ND) | Streptomyces sp. HB202 | Actinobacteria | Mayamycin | IC50 (1.16 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [45] | |

| Spheciospongia vagabunda | Red Sea (ND) | Micrococcus sp. EG45 | Actinobacteria | Microluside A | MIC (12.42 µg/mL) | S. aureus NCTC 8325 | [54] | |

| Isodictya setifera | Ross island, Antartica (30–40 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Proteobacteria | Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid | MIC (>4.99 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [55] | |

| Isodictya setifera | Ross island, Antartica (30–40 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Proteobacteria | Phenazine-1-carboxamide | MIC (>4.99 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [55] | |

| Hymeniacidon perleve | Bohai Sea, China (ND) | Aspergillus versicolor MF359 | Ascomycota | 5-Methoxydihydrosterigmatocystin | MIC (12.5 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [56] | |

| Melophus sp. | Lau group, Fiji islands (10 m) | Penicillium sp. FF001 | Ascomycota | Citrinin | MIC (1.95 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [57] | |

| Petrosia sp. | Jeju island, Korea (20 m) | Aspergillus versicolor | Ascomycota | Averantin | MIC (3.13 µg/mL) | S. aureus SG511 | [58] | |

| Petrosia sp. | Jeju island, Korea (20 m) | Aspergillus versicolor | Ascomycota | Nidurufin | MIC (6.25 µg/mL) | S. aureus SG511 | [58] | |

| Petrosia sp. | Jeju island, Korea (20 m) | Aspergillus versicolor | Ascomycota | Averantin and nidurufin | MIC (3.13 µg/mL) | S. aureus 285 | [58] | |

| Petrosia sp. | Jeju island, Korea (20 m) | Aspergillus versicolor | Ascomycota | Averantin | MIC (1.56 µg/mL) | S. aureus 503 | [58] | |

| Petrosia sp. | Jeju island, Korea (20 m) | Aspergillus versicolor | Ascomycota | Nidurufin | MIC (3.13 µg/mL) | S aureus 503 | [58] | |

| Hymeniacidon perleve | Nanji island, China (ND) | Pseudoalteromonas piscicida NJ6-3-1 | Ascomycota | Norharman (beta-carboline alkaloid) | MIC (50 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [59] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Bogil island, Korea (ND) | Exophiala sp. | Ascomycota | Chlorohydroaspyrones A | MIC (62.5 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [60] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Bogil island, Korea (ND) | Exophiala sp. | Ascomycota | Chlorohydroaspyrones B | MIC (62.5 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [60] | |

| Axinella sp. | South China Sea, China (ND) | Eupenicillium sp. | Ascomycota | αβ-Dehydrocurvularin | MIC (375 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [61] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40, H41 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Diketopiperazine | MIC (512 µg/mL) | S. aureus | [62] | |

| Spongia officinalis | Southeast Coast India (10–15 m) | Streptomyces sp. MAPS15 | Actinobacteria | 2-pyrrolidone | MIC (500 µg/mL) | S. aureus PC6 | [63] | |

| Dysidea herbacea | Koror, Republic Palau (1 m) | Oscillatoria spongeliae | Cyanobacteria | 2-(2′,4′-dibromophenyl)-4,6-dibromophenol | ND | S. aureus | [64] | |

| Hyrtios altum | Aragusuku island, Japan (ND) | Vibrio sp. | Proteobacteria | Trisindoline | DOI (10 mm) | S. aureus | [65] | |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Bidong Island, Malaysia (ND) | Serratia marcescens IBRL USM 84 | Proteobacteria | Prodigiosin | DOI (≤9 mm) | S. aureus | [66] | |

| unidentified | South China Sea (10 m) | Nocardiopsis sp. 13-33-15 and 13-12-13 | Actinobacteria | 1,6-Dihydroxyphenazine | DOI (25 ± 0.6 mm) | S. aureus SJ51 | [67] | |

| 1,6-Dimethoxyphenazine | DOI (21 ± 0.1 mm) | S. aureus SJ51 | ||||||

| Aplysina aerophoba | Banyuls-sur-Mer, France (5–15 m) | Bacillus subtilis A184 | Firmicutes | Surfactin Iturin Fengycin | ND | S. aureus | [68] | |

| Aplysina aerophoba | Banyuls-sur-Mer, France (5–15 m) | Bacillus subtilis A190 | Firmicutes | Surfactin | ND | S. aureus | [68] | |

| Halichondria sp. | West Coast of India (10 m) | Bacillus licheniformis SAB1 | Firmicutes | Indole | DOI (7–10 mm) | S. aureus | [69] | |

| 3-Phenylpropionic | DOI (4–6 mm) | S. aureus | ||||||

| Niphates olemda | Bali Bata National Park, Indonesia (ND) | Curvularia lunata | Ascomycota | 1,3,8-Trihydroxy-6-methoxyanthraquinone (lunatin) | DOI (10 mm) | S. aureus | [70] | |

| Bisanthraquinone cytoskyrin A | ||||||||

| Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Bacillus subtilis MMA7 | Firmicutes | Subtilomycin | ND | S. aureus | [71] | |

| Polymastia boletiformis, Axinella dissimilis and Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound, Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Pseudovibrio sp. W64, W69, W89, W74 | Proteobacteria | Tropodithietic acid | DOI (≥2 mm) | S. aureus | [72] | |

| Polymastia boletiformis, Axinella dissimilis and Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound, Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Pseudovibrio sp. JIC17, W10, W71, W74, W78, W96, WM33, WC15, WC30, HMMA3 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (≥1 mm) | S. aureus | [72] | |

| Polymastia boletiformis, Axinella dissimilis and Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound, Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Pseudovibrio sp. JIC5, JIC6, W62, W63, W65, W99, WC43, W85, W94, WM31, WM34, WM40, WC13, WC21, WC22, WC32, WC41, HC6, | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (≥4 mm) | S. aureus | [72] | |

| Dendrilla nigra | Vizhinjam coast, India (10–15 m) | Streptomyces sp. MSI051 | Ascomycota | Unidentified | MIC (68 ± 2.8 µg protein/mL) | S. aureus | [73] | |

| Hymeniacidon perleve | Nanji Island, China (ND) | Pseudomonas sp. NJ6-3-1 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (3–5 mm) | S. aureus | [74] | |

| Callyspongia spp | Kovalam Coast, India (5–10 m) | Aspergillus flavus GU815344 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (27 mm) | S. aureus | [75] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (20 mm) | S. aureus | [76] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (23 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (20 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (30 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Dragmacidon reticulatus | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Dr31 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (19 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (40 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc32 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (40 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Clathrina aurea | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Ca31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (28 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Paraleucilla magna | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Pm31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (27 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Mycale microsigmatosa | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio denitrificans Mm37 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (20 mm) | S. aureus | [77] | |

| Axinella dissimilis | Gurraig Sound, Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Pseudovibrio Ad30 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | ND | S. aureus | [78] | |

| Pseudoceratina clavata | Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef (14 m) | Salinispora sp. M102, M403, M412, M413, M414, SW10, SW15 and SW17 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (>5 mm) | S. aureus | [79] | |

| Pseudoceratina clavata | Heron Island, Australia (14 m) | Salinispora sp. SW02 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (<5 mm) | S. aureus | [79] | |

| Dendrilla nigra | Southeast coast of India (ND) | Streptomyces sp. BTL7 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (16 mm) | S. aureus | [80] | |

| Mycale sp. | Gulei Port, Fujian, China (ND) | Bacillus sp. HNS004, HNS010 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (15–30 mm) | S. aureus | [81] | |

| Mycale sp. | Gulei Port, Fujian, China (ND) | Vibrio sp. HNS022, HNS029 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (15–30 mm) | S. aureus | [81] | |

| Mycale sp. | Gulei Port, Fujian, China (ND) | Streptomyces sp. HNS054 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (15–30 mm) | S. aureus | [81] | |

| Mycale sp. | Gulei Port, Fujian, China (ND) | Bacillus sp. HNS005 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (10–15 mm) | S. aureus | [81] | |

| Mycale sp. | Gulei Port, Fujian, China (ND) | Cobetia sp. HNS027; Streptomyces sp. HNS047, HNS056; Nocardiopsis sp. HNS048, HNS051, HNS055; Nocardia sp. HNS052 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (10–15 mm) | S. aureus | [81] | |

| Mycale sp. | Gulei Port, Fujian, China (ND) | Bacillus sp. HNS015 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (8–10 mm) | S. aureus | [81] | |

| Mycale sp. | Gulei Port, Fujian, China (ND) | Pseudomonas sp. HNS021 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (8–10 mm) | S. aureus | [81] | |

| Mycale sp. | Gulei Port, Fujian, China (ND) | Cobetia sp. HNS023; Vibrio sp. HNS038; Labrenzia sp. HNS063; Streptomyces sp. HNS049; Nocardiopsis sp. HNS058 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (8–10 mm) | S. aureus | [81] | |

| unidentified | Rovinj, Croatia (3–20 m) | Streptomyces sp. RV15 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (17 mm) | S. aureus | [82] | |

| unidentified | Rovinj, Croatia (3–20 m) | Dietzia sp. EG67 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (13 mm) | S. aureus | [82] | |

| unidentified | Rovinj, Croatia (3–20 m) | Microbacterium sp. EG69 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (13 mm) | S. aureus | [82] | |

| unidentified | Rovinj, Croatia (3–20 m) | Micromonospora sp. RV115 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (12 mm) | S. aureus | [82] | |

| unidentified | Rovinj, Croatia (3–20 m) | Rhodococcus sp. EG33 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (12 mm) | S. aureus | [82] | |

| unidentified | Rovinj, Croatia (3–20 m) | Rubrobacter sp. RV113 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (9 mm) | S. aureus | [82] | |

| Suberites carnosus | Lough Hyne, Co. Cork, Ireland (15 m) | Arthrobacter sp. W13C11 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | ND | S. aureus | [83] | |

| Suberites carnosus | Lough Hyne, Co. Cork, Ireland (15 m) | Pseudovibrio sp. W13S4, W13S21, W13S23, W13S26, W13S31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | ND | S. aureus | [83] | |

| Aplysina aerophoba and Aplysina cavernicola | Marseille and Banyuls sur Mer, France (ND) | Bacillus SB8, SB17, Enterococcus SB91 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (12–16 mm) | S. aureus | [84] | |

| Aplysina aerophoba and Aplysina cavernicola | Marseille and Banyuls sur Mer, France (ND) | Arthrobacter SB95 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (12–16 mm) | S. aureus | [84] | |

| Aplysina aerophoba and Aplysina cavernicola | Marseille and Banyuls sur Mer, France (ND) | unidentified low G + C Gram positive SB122 and SB144 | Unidentified | Unidentified | DOI (12–16 mm) | S. aureus | [84] | |

| Aplysina aerophoba and Aplysina cavernicola | Marseille and Banyuls sur Mer, France (ND) | α-Proteobacteria SB6, SB55, SB63, SB89, SB156, SB197, SB202, SB207, SB214 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (12–16 mm) | S. aureus | [84] | |

| Dysidea granulosa | Kavaratti Island, India (ND) | Enterobacter sp. TTAG | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (22 mm) | S. aureus | [85] | |

| Petrosia ficiformis | Paraggi, Ligurian Sea, Italy (8 m) | Rhodococcus sp. E1 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | ND | S. aureus | [86] | |

| Unidentified | Atlantic coast, USA (ND) | Kocuria palustris F-276,310; Kocuria marina F-276,345 Micrococcus yunnanensis F-256,446 | Actinobacteria | Kocurin | MIC (0.25 µg/mL) | methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | [42,43] | |

| Halichondria japonica | Iriomote island, Japan (ND) | Bacillus cereus QNO3323 | Firmicutes | Thiopeptide YM-266183 | MIC (0.78 µg/mL) | MRSA | [40,41] | |

| Halichondria japonica | Iriomote island, Japan (ND) | Bacillus cereus QNO3323 | Firmicutes | Thiopeptide YM-266184 | MIC (0.39 µg/mL) | MRSA | [40,41] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Kiel Fjord, Baltic Sea, Germany (ND) | Streptomyces sp. HB202 | Actinobacteria | Mayamycin | IC50 (0.58 µg/mL) | MRSA | [45] | |

| Melophus sp. | Lau group, Fiji islands (10 m) | Penicillium sp. FF001 | Ascomycota | Citrinin | MIC (3.90 µg/mL) | MRSA | [57] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Bogil island, Korea (ND) | Exophiala sp. | Ascomycota | Chlorohydroaspyrones A | MIC (125 µg/mL) | MRSA | [60] | |

| Chlorohydroaspyrones B | MIC (62.5 µg/mL) | MRSA | ||||||

| Callyspongia spp. | Gulf of Mannar, India (ND) | Pseudomonas spp. RHLB 12 | Proteobacteria | Chromophore compound | DOI (4 mm) at 50 µM | MRSA | [87] | |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Bidong Island, Malaysia (ND) | Serratia marcescens IBRL USM 84 | Proteobacteria | Prodigiosin | DOI (22.5 mm) | MRSA | [66] | |

| Halichondria sp. | West Coast of India (10 m) | Bacillus licheniformis SAB1 | Firmicutes | Indole 3-phenylpropionic | DOI (4–6 mm) | MRSA | [69] | |

| Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Bacillus subtilis MMA7 | Firmicutes | Subtilomycin | ND | MRSA | [71] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (23 mm) | MRSA | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (27 mm) | MRSA | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (17 mm) | MRSA | [77] | |

| Axinella dissimilis | Gurraig Sound, Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Pseudovibrio Ad30 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | ND | MRSA | [78] | |

| Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound, Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Streptomyces sp. SM2 and SM4 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | ND | MRSA | [88] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (20 mm) | community-associated MRSA | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (22 mm) | community-associated MRSA | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (43 mm) | community-associated MRSA | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (40 mm) | community-associated MRSA | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc32 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (40 mm) | community-associated MRSA | [77] | |

| Clathrina aurea | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Ca31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (17 mm) | community-associated MRSA | [77] | |

| Paraleucilla magna | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Pm31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (25 mm) | community-associated MRSA | [77] | |

| Mycale microsigmatosa | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio denitrificans Mm37 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (20 mm) | community-associated MRSA | [77] | |

| Aplysina aerophoba | Banyuls-sur-Mer, France (15 m) | Bacillus subtilis A202 | Firmicutes | Iturin | ND | multi drug-resistant S. aureus | [68] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Bogil island, Korea (ND) | Exophiala sp. | Ascomycota | Chlorohydroaspyrones A | MIC (125 µg/mL) | multi drug-resistant S. aureus | [60] | |

| Chlorohydroaspyrones B | MIC (125 µg/mL) | multi drug-resistant S. aureus | [60] | |||||

| Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Bacillus subtilis MMA7 | Firmicutes | Subtilomycin | ND | heterogeneous vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) | [71] | |

| Axinella dissimilis | Gurraig Sound, Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Pseudovibrio Ad30 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | ND | hVISA | [78] | |

| Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Streptomyces sp. SM2 and SM4 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | ND | hVISA | [88] | |

| Haliclona simulans | Gurraig Sound Kilkieran Bay, Ireland (15 m) | Streptomyces sp. SM2 and SM4 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | ND | vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) | [88] | |

| Melophus sp. | Lau group, Fiji islands (10 m) | Penicillium sp. FF001 | Ascomycota | Citrinin | MIC (0.97 µg/mL) | rifampicin-resistant S.aureus | [57] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Baltic Sea (ND) | Streptomyces sp. HB202 | Actinobacteria | Mayamycin | IC50 (0.14 µg/mL) | Staphylococcus epidermidis | [45] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Kiel Fjord, Baltic Sea, Germany (ND) | Streptomyces sp. HB202 | Actinobacteria | Streptophenazines G | IC50 (3.57 ± 0.21 µg/mL) | S. epidermidis | [89] | |

| Halichondria panicea | Kiel Fjord, Baltic Sea, Germany (ND) | Streptomyces sp. HB202 | Actinobacteria | Streptophenazines K | IC50 (6.16 ± 0.85 µg/mL) | S. epidermidis | [89] | |

| Axinella corrugata | Arvoredo Biological Marine Reserve, Brazil (ND) | Penicillium sp. | Ascomycota | Dipeptide cis-cyclo(leucyl-tyrosyl) | reducing 85% of biofilm formation at 1000 µg/mL | S. epidermidis | [90] | |

| unidentified sponge | Vizhijam coast (10–12 m) | Aspergillus clavatus MFD15 | Ascomycota | 1H-1,2,4-Triazole-3-carboxaldehyde 5-methyl | MIC (800 ± 10 µg/mL) | S. epidermidis | [91] | |

| Spongia officinalis | Southeast Coast India (10–15 m) | Streptomyces sp. MAPS15 | Actinobacteria | 2-Pyrrolidone | MIC (500 µg/mL) | S. epidermidis PC5 | [63] | |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Bidong Island, Malaysia (ND) | Serratia marcescens IBRL USM 84 | Proteobacteria | Prodigiosin | DOI (<9 mm) | S. epidermidis | [66] | |

| Aplysina aerophoba | Banyuls-sur-Mer, France (5–15 m) | Bacillus subtilis A184 | Firmicutes | Surfactin Iturin Fengycin | ND | S. epidermidis | [68] | |

| Aplysina aerophoba | Banyuls-sur-Mer, France (5–15 m) | Bacillus subtilis A190 | Firmicutes | Surfactin | ND | S. epidermidis | [68] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (35 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (30 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (28 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Dragmacidonreticulatus | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Dr31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (20 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (45 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc32 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (38 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Clathrina aurea | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Ca31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (25 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Paraleucilla magna | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Pm31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (35 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Mycale microsigmatosa | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio denitrificans Mm37 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (30 mm) | S. epidermidis | [77] | |

| Pseudoceratina clavata | Heron Island, Australia (14 m) | Salinispora sp. M102, M403, M412, M413, M414, SW10, SW15, SW17 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (<5 mm) | S. epidermidis | [79] | |

| Pseudoceratina clavata | Heron Island, Australia (14 m) | Salinispora sp. SW02 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (>5 mm) | S. epidermidis | [79] | |

| Callyspongia diffusa | Bay of Bengal, India (10–15 m) | Streptomyces sp. CPI 13 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (6.6 mm) | S. epidermidis | [92] | |

| Micromonospora sp. CPI 12 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (6.6 mm) | S. epidermidis | [92] | |||

| Saccharomonospora sp. CPI 3 | Actinobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (6.3 mm) | S. epidermidis | [92] | |||

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (25 mm) | S. epidermidis 57s (susceptibile to amp, cip, pen, tet) | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (25 mm) | S. epidermidis 57s | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (33 mm) | S. epidermidis 57s | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (30 mm) | S. epidermidis 57s | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc32 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (30 mm) | S. epidermidis 57s | [77] | |

| Clathrina aurea | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Ca31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (15 mm) | S. epidermidis 57s | [77] | |

| Paraleucilla magna | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Pm31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (17 mm) | S. epidermidis 57s | [77] | |

| Mycale microsigmatosa | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio denitrificans Mm37 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (16 mm) | S. epidermidis 57s | [77] | |

| Xestospongia testudinaria | Weizhou coral reef, China (ND) | Aspergillus sp. | Ascomycota | (Z)-5-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-(6′-methylhept-2′-en-2′-yl)phenol | MIC (4.66 µg/mL) | Staphylococcus albus | [48] | |

| Aspergiterpenoid A | MIC (1.24 µg/mL) | |||||||

| (−)-5-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-(2′,6′,6′-trimethyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)phenol | MIC (1.26 µg/mL) | |||||||

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (27 mm) | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (27 mm) | S. haemolyticus | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (35 mm) | S. haemolyticus | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (40 mm) | S. haemolyticus | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc32 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (40 mm) | S. haemolyticus | [77] | |

| Clathrina aurea | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Ca31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (38 mm) | S. haemolyticus | [77] | |

| Paraleucilla magna | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Pm31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (40 mm) | S. haemolyticus | [77] | |

| Mycale microsigmatosa | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio denitrificans Mm37 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (43 mm) | S. haemolyticus | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (19 mm) | S. haemolyticus 109s (susceptible to amp, gen, oxa, pen) | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (15 mm) | S. haemolyticus 109s | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (35 mm) | S. haemolyticus 109s | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (31 mm) | S. haemolyticus 109s | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc32 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (36 mm) | S. haemolyticus 109s | [77] | |

| Clathrina aurea | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Ca31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (23 mm) | S. haemolyticus 109s | [77] | |

| Paraleucilla magna | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Pm31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (30 mm) | S. haemolyticus 109s | [77] | |

| Mycale microsigmatosa | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio denitrificans Mm37 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (20 mm) | S. haemolyticus 109s | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (31mm) | Staphylococcus hominis | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (28 mm) | S. hominis | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (37 mm) | S. hominis | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (41 mm) | S. hominis | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc32 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (43 mm) | S. hominis | [77] | |

| Clathrina aurea | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Ca31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (23 mm) | S. hominis | [77] | |

| Paraleucilla magna | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio ascidiaceicola Pm31 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (25 mm) | S. hominis | [77] | |

| Mycale microsigmatosa | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudovibrio denitrificans Mm37 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (24 mm) | S. hominis | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H40 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (25 mm) | Staphylococcus hominis 79s (susceptible to amp, pen) | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas fluorescens H41 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (27 mm) | S. hominis 79s | [77] | |

| Haliclona sp. | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa H51 | Proteobacteria | Unidentified | DOI (20 mm) | S. hominis 79s | [77] | |

| Petromica citrina | Cagarras Archipelago, Brazil (4–20 m) | Bacillus pumilus Pc31 | Firmicutes | Unidentified | DOI (35 mm) | S. hominis 79s | [77] | |