Sulphated Polysaccharides from Ulva clathrata and Cladosiphon okamuranus Seaweeds both Inhibit Viral Attachment/Entry and Cell-Cell Fusion, in NDV Infection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

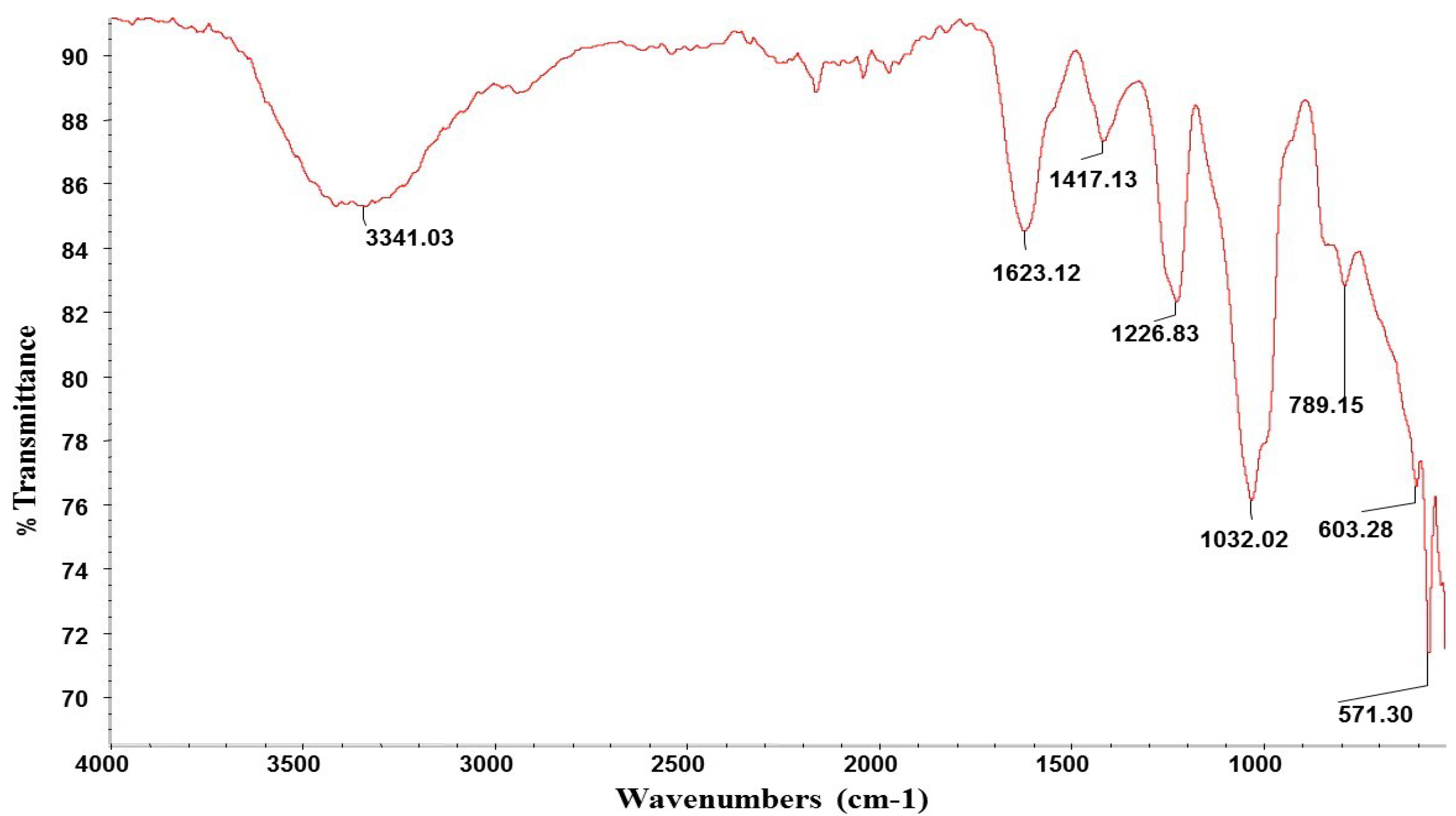

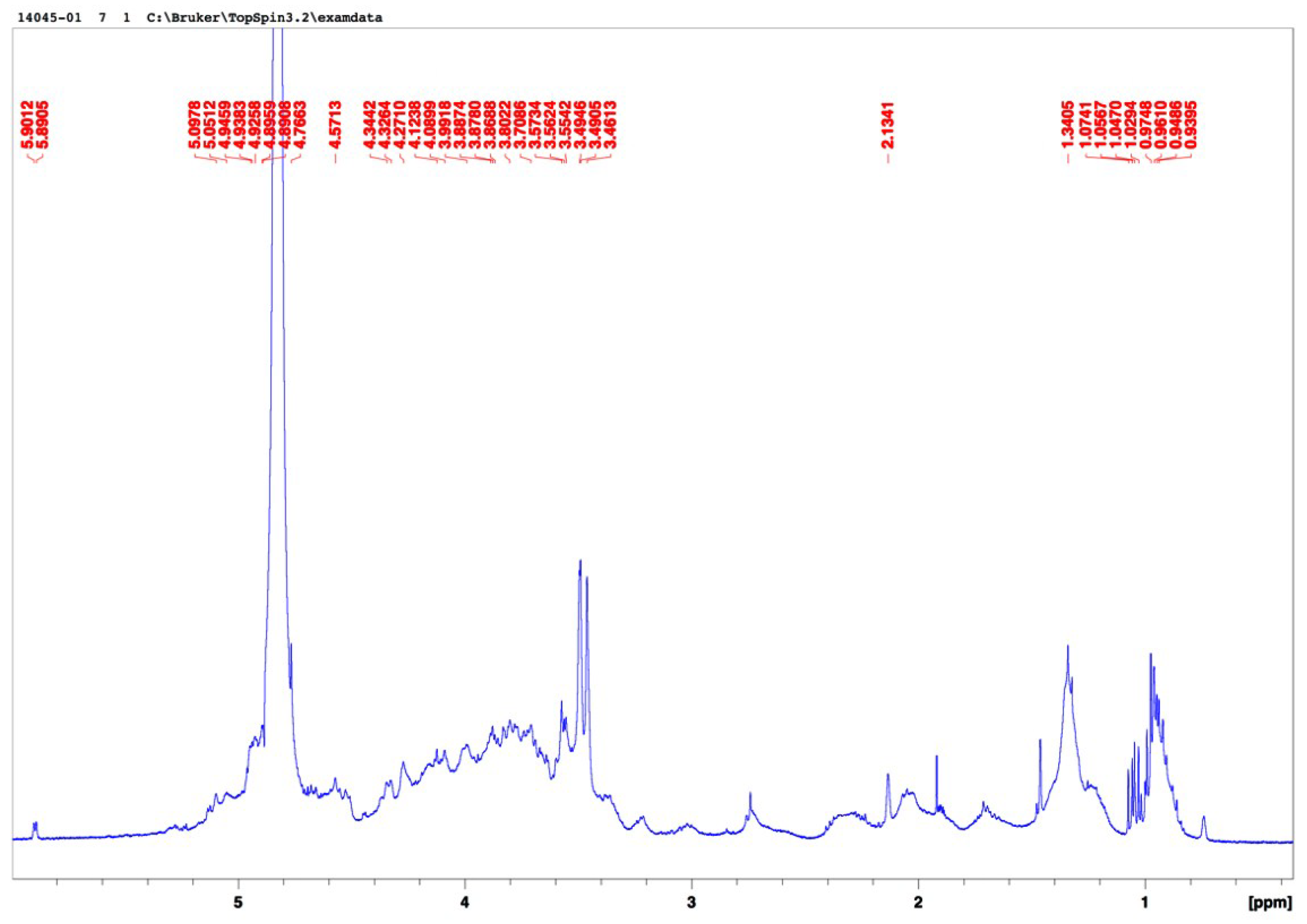

2.1. Composition of Ulva Clathrata Powder and Ulvan Extract

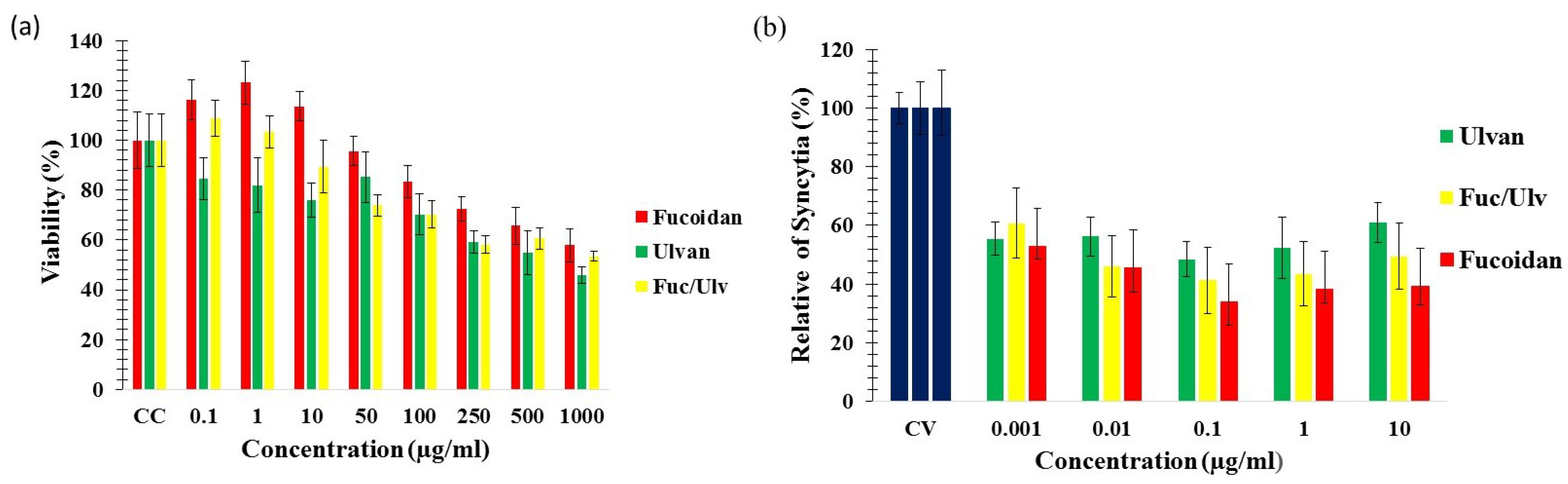

2.2. Cytotoxicity of the SP

| Polysaccharide | Vero Cell Line | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CC50 (μg/mL) a | IC50 (μg/mL) b | SI c | |

| Fucoidan | 1136 | 0.01 | 113,633 |

| Ulvan | 810 | 0.1 | 8102.5 |

| Fuc/Ulv | 823 | 0.01 | 82,325 |

2.4. Virucidal Activity of Ulvan

| Time | Viral Titer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 × 104 TCID50 | 1 × 105 TCID50 | |||

| CC | ― | ― | ||

| CV | +++ | +++ | ||

| Ulvan concentrations | 10 μg/mL | 0 h | +++ | +++ |

| 10 μg/mL | 3 h | +++ | +++ | |

| 10 μg/mL | 6 h | +++ | +++ | |

| 100 μg/mL | 0 h | +++ | +++ | |

| 100 μg/mL | 3 h | +++ | +++ | |

| 100 μg/mL | 6 h | +++ | +++ | |

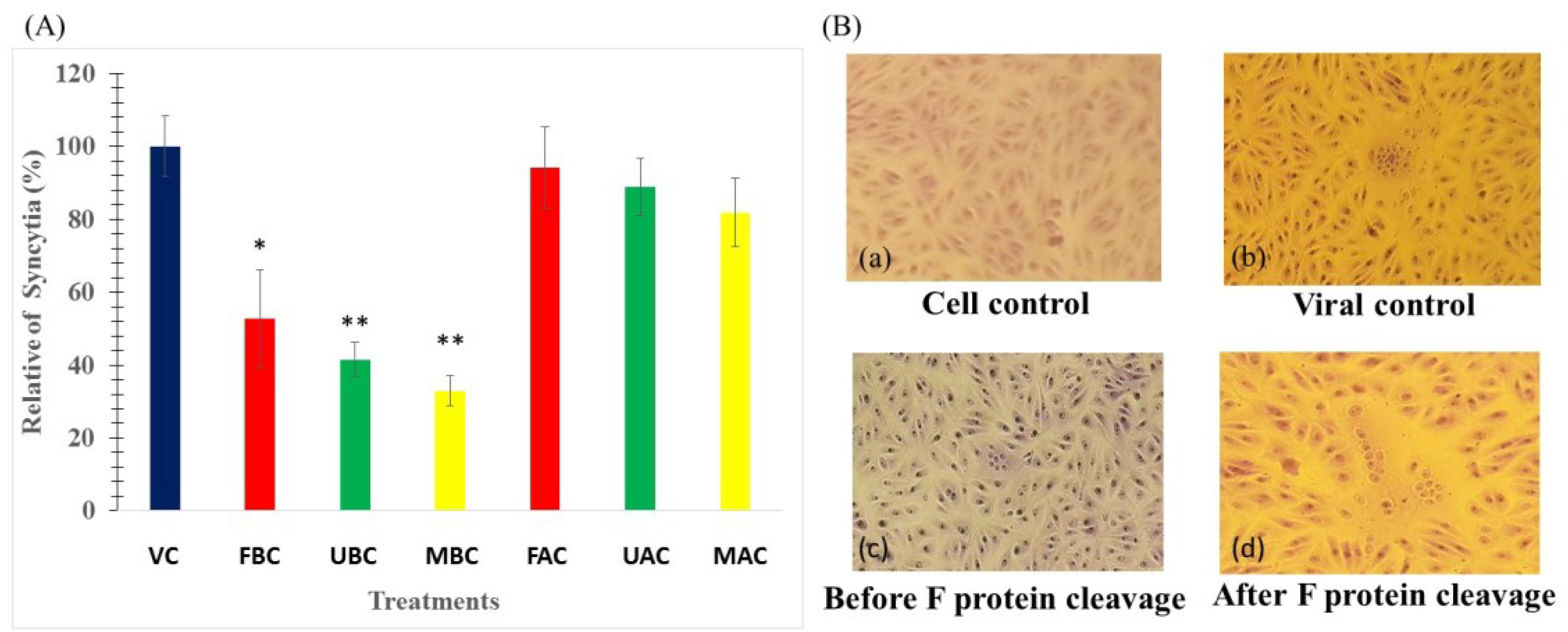

2.5. Ability of the SP to Block NDV-Induced Cell-Cell Fusion

3. Experimental Section

3.2. Cell Line and VIRUS

3.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

3.4. Virucidal Assay

3.6. Fusion Inhibition Assay

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gerber, P.; Dutcher, J.D.; Adams, E.V.; Sherman, J.H. Protective effect of seaweed extracts for chicken embryos infected with influenza B or mumps virus. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1958, 99, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damonte, E.B.; Matulewicz, M.C.; Cerezo, A.S. Sulfated seaweed polysaccharides as antiviral agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 2399–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizondo-Gonzalez, R.; Cruz-Suarez, L.E.; Ricque-Marie, D.; Mendoza-Gamboa, E.; Rodriguez-padilla, C.; Trejo-Avila, L.M. In vitro characterization of the antiviral activity of fucoidan from Cladosiphon okamuranus against Newcastle Disease Virus. Virol. J. 2012, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trejo-Avila, L.M.; Morales-Martínez, M.L.; Ricque-Marie, D.; Cruz-Suarez, L.E.; Zapata-Benavides, P.; Morán-Santibañez, K.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C. In vitro anti-canine distemper virus activity of fucoidan extracted from the brown alga Cladosiphon okamuranus. Virus Dis. 2014, 25, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patarra, R.F.; Paiva, L.; Neto, A.I.; Lima, E.; Baptista, J. Nutritional value of selected macroalgae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, M.; Kaeffer, B. Seaweed dietary fibres: Structure, physico-chemical and biological properties relevant to intestinal physiology. Sci. Aliments 1997, 17, 563–584. [Google Scholar]

- Lahaye, M.; Robic, A. Structure and functional properties of ulvan, a polysaccharide from green seaweeds. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, A.; Sousa, R.A.; Reis, R.L. In vitro cytotoxicity assessment of ulvan, a polysaccharide extracted from green algae. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. Synthesis and antihyperlipidemic activity of acetylated derivative of ulvan from Ulva pertusa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 50, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, G.S.; Soares, A.R.; Martins, F.O.; Albuquerque, M.C.; Costa, S.S.; Yoneshigue-Valentin, Y.; Gestinari, L.M.; Santos, N.; Romanos, M.T. Antiviral activity of green marine alga Ulva fasciata on the replication of human metapneumovirus. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2010, 52, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaulneau, V.; Laffite, C.; Jacquet, C.; Fournier, S.; Salamagne, S.; Briand, X.; Esquerré- Tugayé, M.T.; Dumas, B. Ulvan, a sulfated polysaccharide from green algae, activates plant immunity through the jasmonic acid signaling pathway. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarsa, M.; Han, J.H.; Kim, C.Y.; You, S.G. Molecular characteristics and immunomodulatory activities of water soluble sulfated polysaccharides from Ulva pertusa. J. Med. Food 2012, 15, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiro, J.M.; Castro, C.; Arranz, J.A.; Lamas, J. Immunomodulating activities of acidic sulphated polysaccharides obtained from the seaweed Ulva rigida C. Agardh. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007, 7, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, W.; Zang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Sulfated polysaccharides from marine green algae Ulva conglobata and their anticoagulant activity. J. Appl. Phycol. 2006, 18, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rodríguez, A.; Mawhinney, T.P.; Ricque-Marie, D.; Cruz-Suárez, L.E. Chemical composition of cultivated seaweed Ulva clathrata (Roth) C. Agardh. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robic, A.; Sassi, J-F.; Lahaye, M. Impact of stabilization treatments of the green seaweed Ulva rotundata (Chlorophyta) on the extraction yield, the physico-chemical and rheological properties of ulvan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 74, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A. Determination of sulfate in water samples. Sulphur. Inst. 1974, 10, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Quemener, B.; Marot, C.; Mouillet, L.; da Riz, V.; Diris, J. Quantitative analysis of hydrocolloids in food systems by methanolysis coupled to reverse HPLC. Part 1. Gelling carrageenans. Food Hydrocoll. 2000, 14, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robic, A.; Rondeau-Mouro, C.; Sassi, J.-F.; Lerat, Y.; Lahaye, M. Structure and interactions of ulvan in the cell wall of the marine green algae Ulva rotundata (Ulvales, Chlorophyceae). Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.J.; Decanini, E.L.; Afonso, C.L. Newcastle disease: Evolution of genotypes and the related diagnostic challenges. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2010, 10, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, M.A. Virus taxonomy-Houston 2002. Arch. Virol. 2002, 147, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, R.A.; Parks, G.D. Paramyxoviridae: The viruses and their replication. In Fields Virology, 5th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Lippincott WIlliams & Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 1449–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Taboada, C.; Millán, R.; Miguez, I. Composition, nutritional aspects and effect on serum parameters of marine algae Ulva rigida. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaich, H.; Garna, H.; Besbes, S.; Paquot, M.; Blecker, C.; Attia, H. Effect of extraction conditions on the yield and purity of ulvan extracted from Ulva lactuca. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 31, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quemener, B.; Lahaye, M. Sugar determination in ulvans by a chemical-enzymatic method coupled to high performance anion exchange chromatography. J. Appl. Phycol. 1997, 9, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeReviers, B.; Leproux, A. Characterization of polysaccharides from Enteromorpha intestinalis (L.) Link. Chlorophyta. Carbohydr. Polym. 1993, 22, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, E.; McDowell, R.H. Chemistry and Enzymology of Marine Algal Polysaccharides; Academic Press: London, UK, 1967; p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, B.; Lahaye, M. Cell-wall polysaccharides from the marine green alga Ulva “rigida” (Ulvales Chlorophyta)-Chemical structure of ulvan. Carbohydr. Res. 1995, 274, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robic, A.; Bertrand, D.; Sassi, J.F.; Lerat, Y.; Lahaye, M. Determination of the chemical composition of ulvan, a cell wall polysaccharide from Ulva spp. (Ulvales, Chlorophyta) by FT-IR and chemometrics. J. Appl. Phycol. 2009, 21, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Garibay, E.; Zertuche-González, J.A.; Pacheco-Ruíz, I. Isolation and chemical characterization of algal polysaccharides from the green seaweed Ulva clathrata (Roth) C. Agardh. J. Appl. Phycol. 2010, 23, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengzhan, Y.; Quanbin, Z.; Ning, L.; Zuhong, X.; Yanmei, W.; Zhi’en, L. Polysaccharides from Ulva pertusa (Chlorophyta) and preliminary studies on their antihyperlipidemia activity. J. Appl. Phycol. 2003, 15, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiellini, F.; Morelli, A. Ulvan: A Versatile Platform of Biomaterials from Renewable Resources. In Biomaterials—Physics and Chemistry; Pignatello, R., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Yin, Z.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, A.; Jia, R.; Yuan, G.; Xu, J.; Fan, Q.; Dai, S.; Lu, H.; et al. Antiviral activity of sulfated Chuanmingshen violaceum polysacchare against Newcastle disease virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 2164–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, V.; Rouseva, R.; Kolarova, M.; Serkedjieva, J.; Rachev, R.; Manolova, N. Isolation of a polysaccharide with antiviral effect from Ulva lactuca. Prep. Biochem. 1994, 24, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiu, Y.H.; Chan, Y.L.; Li, T.L.; Wu, C.J. Inhibition of Japanese encephalitis virus infection by the sulfated polysaccharide extracts from Ulva lactuca. Mar. Biotechnol. (N.Y.) 2012, 14, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Pavy, M.; Young, N.; Freeman, C.; Lobigs, M. Antiviral effect of the heparan sulfate mimetic, PI-88, against dengue and encephalitic flaviviruses. Antivir. Res. 2006, 69, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, T.; Hayashi, K.; Kanekiyo, K.; Ohta, Y.; Lee, J.B. Promising antiviral Glyco-molecules from an edible alga. In Combating the Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Drug Discovery Approaches; Torrence, P.F., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 166–182. [Google Scholar]

- Vlieghe, P.; Clerc, T.; Pannecouque, C.; Witvrouw, M.; de Clercq, E.; Salles, J.P.; Kraus, J.L. Synthesis of new covalently bound kappa-carrageenan-AZT conjugates with improved anti-HIV activities. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takebe, Y.; Saucedo, C.J.; Lund, G.; Uenishi, R.; Hase, S.; Tsuchiura, T.; Kneteman, N.; Ramessar, K.; Tyrrell, D.L.; Shirakura, M.; et al. Antiviral lectins from red and blue-green algae show potent in vitro and in vivo activity against hepatitis C virus. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 621–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.C.; Talalay, P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: The combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1984, 22, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.Y.; Ly, J.K.; Myrick, F.; Goodman, D.; White, K.L.; Svarovskaia, E.S.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Miller, M.D. The triple combination of tenofovir, emtricitabine and efavirenz shows synergistic anti-HIV-1 activity in vitro: A mechanism of action study. Retrovirology 2009, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, M.B.; Campeol, N.; Lalonde, R.G.; Brenner, B.; Wainberg, M.A. Didanosine, interferon-alfa and ribavirin: A highly synergistic combination with potential activity against HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus. AIDS 2003, 17, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.H.; Crouch, J.Y.; Chou, T.C.; Hsiung, G.D. Combined antiviral effects of paired nucleosides against guinea pig cytomegalovirus replication in vitro. J. Antivir. Res. 1990, 14, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damonte, E.B.; Matulewicz, M.C.; Cerezo, A.S.; Coto, C. Herpes simplex virus inhibitory sulfated xylogalactans from the red seaweed Nothogenia fastigiata. Chemotherapy 1996, 42, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, P.; Pujol, C.A.; Carlucci, M.J.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Damonte, E.B.; Ray, B. Anti-herpetic activity of a sulfated xylomannan from Scinaia hatei. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 2193–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouhlal, R.; Haslin, C.; Chermann, J.-C.; Colliec-Jouault, S.; Sinquin, C.; Simon, G.; Cerantola, S.; Riadi, H.; Bourgougnon, N. Antiviral activities of sulfated polysaccharides isolated from Sphaerococcus coronopifolius (Rhodophytha, Gigartinales) and Boergeseniella thuyoides (Rhodophyta, Ceramiales). Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 1187–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paskaleva, E.E.; Lin, X.; Li, W.; Cotter, R.; Klein, M.T.; Roberge, E.; Yu, E.K.; Clark, B.; Veille, J.C.; Liu, Y.; et al. Inhibition of highly productive HIV-1 infection in T cells, primary human macrophages, microglia, and astrocytes by Sargassum fusiforme. AIDS Res. Ther. 2006, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyberg, K.; Ekblad, M.; Bergström, T.; Freeman, C.; Parish, C.R.; Ferro, V.; Trybala, E. The low molecular weight heparan sulfate-mimetic, PI-88, inhibits cell-to-cell spread of herpes simplex virus. Antivir. Res. 2004, 63, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagno, V.; Donalisio, M.; Civra, A.; Volante, M.; Veccelli, E.; Oreste, P.; Rusnati, M.; Lembo, D. Highly sulfated K5 Escherichia coli polysaccharide derivatives inhibit respiratory syncytial virus infectivity in cell lines and human tracheal-bronchial histocultures. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4782–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tako, M.; Yoza, E.; Thoma, S. Chemical characterization of acetyl fucoidan and alginate from commercially cultured Cladosiphon okamuranus. Bot. Mar. 2000, 43, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, B. Aquatic Surface Barriers and Methods for Culturing Seaweed; World Intelectual Property Organization: Davis, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Method 984.13. In Official Methods of Analysis, 16th ed., 3rd revision; Cunniff, P., Ed.; AOAC International (formerly The Association of Official Analytical Chemists): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1997; p. 1033. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tien, P.; Gao, G.F. Design and characterization of viral polypeptide inhibitors targeting Newcastle disease virus fusion. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 354, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguilar-Briseño, J.A.; Cruz-Suarez, L.E.; Sassi, J.-F.; Ricque-Marie, D.; Zapata-Benavides, P.; Mendoza-Gamboa, E.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; Trejo-Avila, L.M. Sulphated Polysaccharides from Ulva clathrata and Cladosiphon okamuranus Seaweeds both Inhibit Viral Attachment/Entry and Cell-Cell Fusion, in NDV Infection. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 697-712. https://doi.org/10.3390/md13020697

Aguilar-Briseño JA, Cruz-Suarez LE, Sassi J-F, Ricque-Marie D, Zapata-Benavides P, Mendoza-Gamboa E, Rodríguez-Padilla C, Trejo-Avila LM. Sulphated Polysaccharides from Ulva clathrata and Cladosiphon okamuranus Seaweeds both Inhibit Viral Attachment/Entry and Cell-Cell Fusion, in NDV Infection. Marine Drugs. 2015; 13(2):697-712. https://doi.org/10.3390/md13020697

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguilar-Briseño, José Alberto, Lucia Elizabeth Cruz-Suarez, Jean-François Sassi, Denis Ricque-Marie, Pablo Zapata-Benavides, Edgar Mendoza-Gamboa, Cristina Rodríguez-Padilla, and Laura María Trejo-Avila. 2015. "Sulphated Polysaccharides from Ulva clathrata and Cladosiphon okamuranus Seaweeds both Inhibit Viral Attachment/Entry and Cell-Cell Fusion, in NDV Infection" Marine Drugs 13, no. 2: 697-712. https://doi.org/10.3390/md13020697

APA StyleAguilar-Briseño, J. A., Cruz-Suarez, L. E., Sassi, J.-F., Ricque-Marie, D., Zapata-Benavides, P., Mendoza-Gamboa, E., Rodríguez-Padilla, C., & Trejo-Avila, L. M. (2015). Sulphated Polysaccharides from Ulva clathrata and Cladosiphon okamuranus Seaweeds both Inhibit Viral Attachment/Entry and Cell-Cell Fusion, in NDV Infection. Marine Drugs, 13(2), 697-712. https://doi.org/10.3390/md13020697