Kinesiology Taping in Grade I–II Meniscus Injuries: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

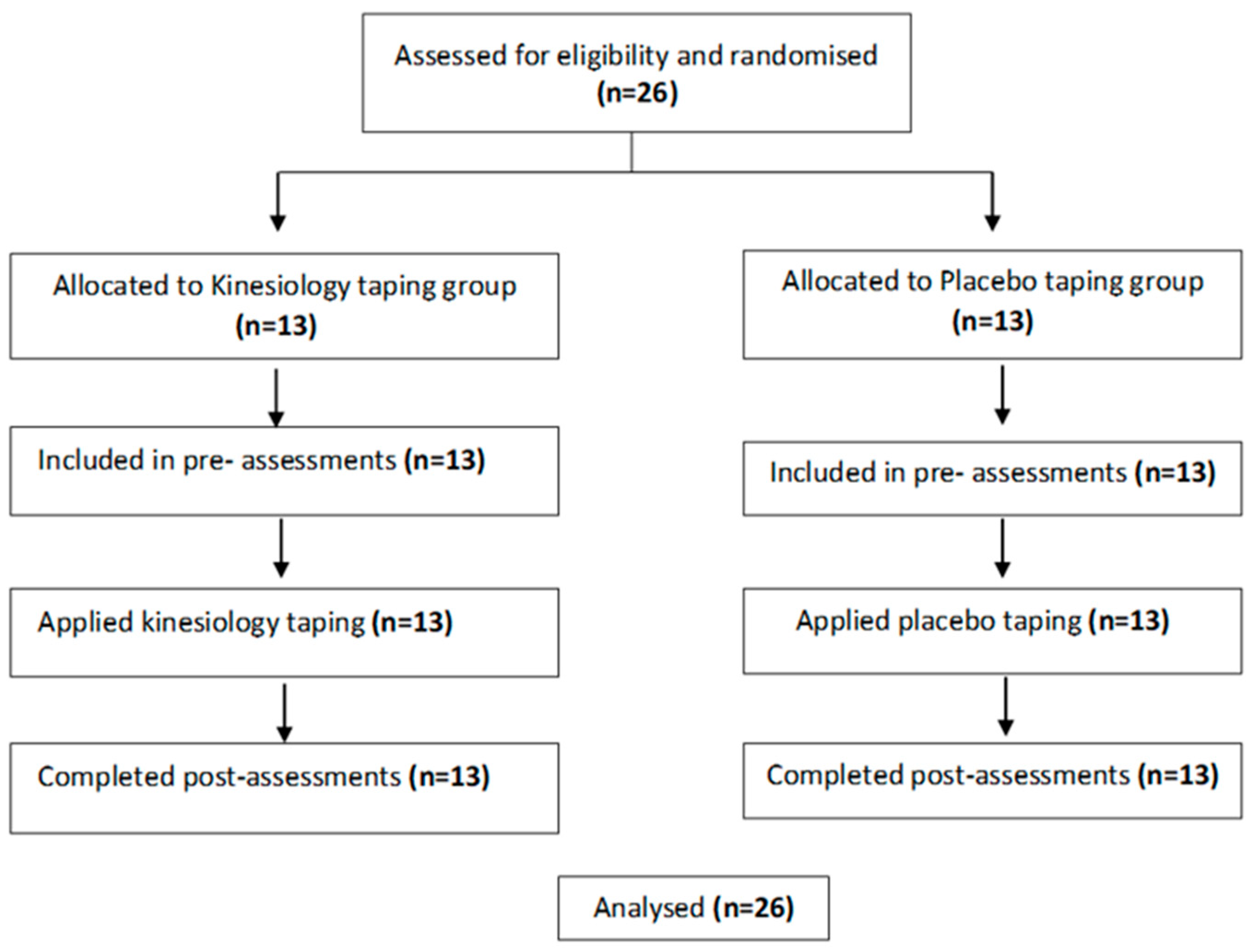

2.1. Study Design and Participants

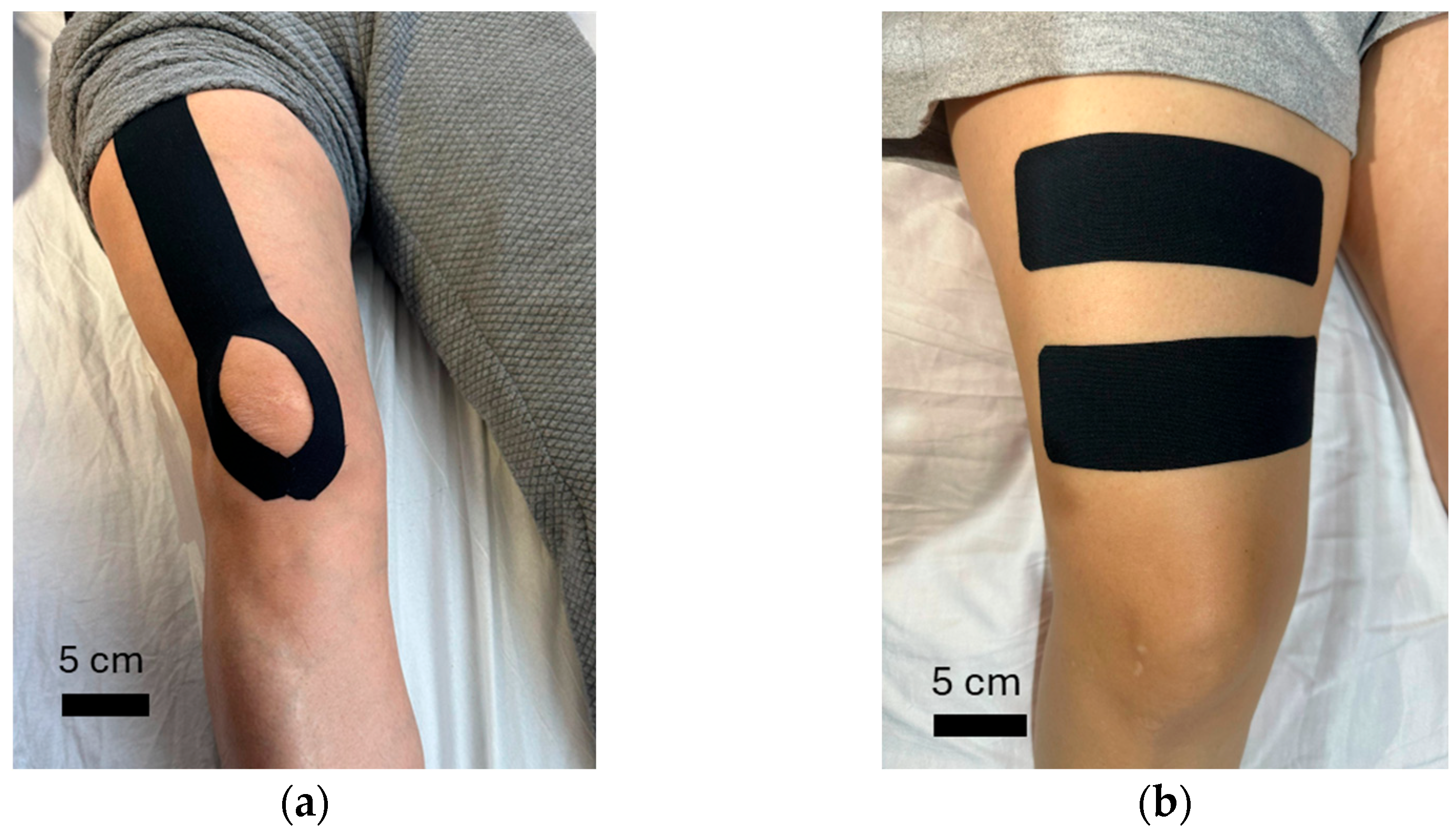

2.2. Intervention Procedures

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measurements

4. Discussion

Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KT | Kinesiology Taping |

| PT | Placebo Taping |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| TSK | Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia |

| ROM | Range of Motion |

| SF-36 | Short Form of 36 Health Survey |

References

- Kuczyński, N.; Boś, J.; Białoskórska, K.; Aleksandrowicz, Z.; Turoń, B.; Zabrzyńska, M.; Bonowicz, K.; Gagat, M. The Meniscus: Basic Science and Therapeutic Approaches. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Park, Y.B.; Kim, B.S.; Lee, D.H.; Pujol, N. Incidence of associated lesions of multiligament knee injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211010410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuffrida, A.; Di Bari, A.; Falzone, E.; Iacono, F.; Kon, E.; Marcacci, M.; Gatti, R.; Di Matteo, B. Conservative vs. surgical approach for degenerative meniscal injuries: A systematic review of clinical evidence. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 2874–2885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, X.; Shen, X.; Chen, L.; Gong, H. Effectiveness of Kinesio tape in the treatment of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2024, 103, e38438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melese, H.; Alamer, A.; Hailu Temesgen, M.; Nigussie, F. Effectiveness of kinesio taping on the management of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Pain Res. 2020, 13, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X. Influence of Kinesio Taping on the Level of Inflammatory Factors in the Joint Fluid of Athletes with Early Meniscus Injury. Front. Sport Res. 2019, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, S.H.P.; Alatawi, S.F. Effectiveness of Kinesio taping and conventional physical therapy in the management of knee osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 192, 2223–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobiech, M.; Czępińska, A.; Zieliński, G.; Zawadka, M.; Gawda, P. Does application of lymphatic drainage with kinesiology taping have any effect on the extent of edema and range of motion in early postoperative recovery following primary endoprosthetics of the knee joint? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Elshiwi, F.; Mudawi, R. Short term effect of kinesio taping on functional disability and quality of life ın treatment of patients with planter fasciitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 5969. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchino, G.; Grassa, D.; Bove, A.; Salvini, M.; Kaplan, R.; Di Gialleonardo, E.; Forconi, F.; Maccauro, G.; Vitiello, R. The Effects of Kinesio Tape on Acute Ankle Sprain: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.; Makram, A.M.; Makram, O.M.; Elfaituri, M.K.; Morsy, S.; Ghozy, S.; Zayan, A.H.; Nam, N.H.; Zaki, M.M.M.; Allison, E.L.; et al. Efficacy of kinesio taping compared to other treatment modalities in musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Sports Med. 2023, 31, 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joveini, G.; Boozari, S.; Mohamadi, S.; Jafari, H. Does lower limb kinesio taping affect pain, muscle strength, and balance following fatigue in healthy subjects? A systematic review and meta analysis of parallel randomized controlled trials. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vithoulka, I.A.; Beneka, A.B.; Malliou, P.B.; Aggelousis, N.B.; Karatsolis, K.; Diamantopoulos, K. The effects of Kinesio-Taping® on quadriceps strength during isokinetic exercise in healthy non athlete women. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2010, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, J.F.; de Almeida Novello, A.; Nakaoka, G.B.; Dos Reis, A.C.; Fukuda, T.Y.; Bryk, F.F. Kinesio taping effect on quadriceps strength and lower limb function of healthy individuals: A blinded, controlled, randomized, clinical trial. Phys. Ther. Sport 2016, 18, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revill, S.I.; Robinson, J.O.; Rosen, M.; Hogg, M.I. The reliability of a linear analogue for evaluating pain. Anaesthesia 1976, 31, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, O.; Yakut, Y.; Uygur, F.; Ulug, N. Turkish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia and its test-retest reliability. Turk. J. Physiother. Rehabil. Rehabil. 2011, 22, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Treleaven, J. The effect of neck torsion on joint position error in subjects with chronic neck pain. Man. Ther. 2013, 18, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, C.; Harput, G.; Kinikli, G.I.; Kose, N.; Deniz, H.G. Correlation of force sense error test measured by a pressure biofeedback unit and EMG activity of quadriceps femoris in healthy individuals. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2019, 49, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otman, S.A.; Köse, N. Antropometrik Ölçümler: Tedavi Hareketlerinde Temel Değerlendirme Prensipleri; Yücel Ofset Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dover, G.; Powers, M.E. Reliability of joint position sense and force-reproduction measures during internal and external rotation of the shoulder. J. Athl. Train. 2003, 38, 304. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, R.; Trindade, R.; Gonçalves, R.S. The effect of kinesiology tape on knee proprioception in healthy subjects. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2016, 20, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocyigit, H. Kisa Form-36 (KF-36) nin Turkce versiyonunun guvenirligi vegecerliligi. [Validity and reliability of Turkish version of SF-36]. J. Drug. Ther. 1999, 12, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Zieliński, G. Effect Size Guidelines for Individual and Group Differences in Physiotherapy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 106, 1844–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral 698 sciences. Stat. Power Anal. Behav. Sci. 1988, 2, 495. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, X.X.; Wang, L. Effect of short-term kinesiology taping on knee proprioception and quadriceps performance in healthy individuals. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 603193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.Y.; Kim, E.H.; Kim, J.; Yoon, Y.W. Kinesio taping improves pain, range of motion, and proprioception in older patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 94, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataş, A.; Abit Kocaman, A.; Karaca, Ş.B.; Kasikci Çavdar, M. Acute Effect of Kinesiology Taping on Muscle Activation, Functionality and Proprioception in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2024, 131, 446–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.Y.; Hu, M.T.; Yen, Y.Y.; Lan, S.J.; Lee, S.D. Kinesio Taping relieves pain and improves isokinetic not isometric muscle strength in patients with knee osteoarthritis—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshiwi, A.M.F.; Asiri, R.M.Y.; Alasmry, S.A.G. Short Term Effect of Kinesio Taping on Functional Disability and Quality of Life in Treatment of Patients with Planter Fasciitis: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 5969–5979. [Google Scholar]

- Atta, A.S.; Atia, N.R.; El-Sadany, H.M.; Ibrahim, R.A. Effect of nursing care by using swedish massage, kinesio tape for knee osteoarthritis patients on pain, functional status and quality of life. Int. Egypt. J. Nurs. Sci. Res. 2022, 2, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wageck, B.; de Noronha, M.; Nunes, G.S.; Bohen, N.; Santos, G.M. Effects of Kinesio-Taping in pain and quality of life in the elderly with knee osteoarthritis—A randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2015, 101, e304–e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donec, V.; Kubilius, R. The effectiveness of Kinesio Taping® for pain management in knee osteoarthritis: A randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2019, 11, 1759720X19869135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocyigit, F.; Turkmen, M.B.; Acar, M.; Guldane, N.; Kose, T.; Kuyucu, E.; Erdil, M. Kinesio taping or sham taping in knee osteoarthritis? A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirih, A.; Kozinc, Ž. Kinesio taping-What have we learned in 50 years?: A review of existing systematic reviews. Hrvat. Rev. Za Rehabil. Istraživanja 2024, 60, 119–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celenay, S.T.; Mete, O.; Akan, S.; Yildirim, N.U.; Erten, S. Comparison of the effects of stabilization exercise plus kinesio taping and stabilization exercise alone on pain and well-being in fibromyalgia. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 38, 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, H.; Eroğlu, S.; Akbayrak, T. The effect of kinesio taping and lifestyle changes on pain, body awareness and quality of life in primary dysmenorrhea. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röijezon, U.; Clark, N.C.; Treleaven, J. Proprioception in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Part 1: Basic science and principles of assessment and clinical interventions. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.D.; Finniss, D.G.; Benedetti, F. A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: Recent advances and current thought. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 565–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedhom, M.G. Efficacy of kinesio-taping versus phonophoresis on knee osteoarthritis: An experimental study. Int. J. Physiother. 2016, 3, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, E.K.; Mustafaoglu, R.; Birinci, T.; Ozdincler, A.R. Does Kinesio taping of the knee improve pain and functionality in patients with knee osteoarthritis?: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 96, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Liang, J.; Feng, J.; Cao, Y.; Luo, J.; Liao, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, Z.; He, J.; Wu, S. Medial meniscus tears are most prevalent in type I ACL tears, while type I ACL tears only account for 8% of all ACL tears. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 2349–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limroongreungrat, W.; Boonkerd, C. Immediate effect of ACL kinesio taping technique on knee joint biomechanics during a drop vertical jump: A randomized crossover controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodzka-Ciechanowicz, K.; Głąb, G.; Ślusarski, J.; Gądek, A.; Nawara, J. Does kinesiotaping can improve static stability of the knee after anterior cruciate ligament rupture? A randomized single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kinesiology Taping Group (n = 13) | Placebo Taping Group (n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 41.07 ± 10.82 | 43.92 ± 10.45 |

| Dominant side | ||

| Right | 12 (92%) | 12 (92%) |

| Left | 1 (8%) | 1 (8%) |

| Injured side | ||

| Right | 6 (46%) | 6 (46%) |

| Left | 7 (54%) | 7 (54%) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 6 (46%) | 6 (46%) |

| Male | 7 (54%) | 7 (54%) |

| Assessments | Kinesiology Taping Group (n = 13) | Placebo Taping Group (n = 13) | p-Value † | Cohen’s d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Change (Post-Pre, Mean ± SD) | Pre | Post | Change (Post-Pre, Mean ± SD) | |||

| Pain | 5.15 ± 1.67 | 3.38 ± 1.32 | −1.76 ± 1.36 | 4.53 ± 1.56 | 2.23 ± 1.42 | −2.3 ± 1.18 | 0.29 | 0.42 |

| Fear of movement | 39.69 ± 5.67 | 33.46 ± 9.04 | −6.23 ± 5.79 | 35.92 ± 5.4 | 33.15 ± 5.09 | −2.76 ± 1.42 | 0.056 | 0.82 |

| Knee extension muscle strength | 13.3 ± 2.22 | 14.86 ± 2.69 | 1.55 ± 1.44 | 12.43 ± 1.38 | 13.3 ± 1.78 | 0.86 ± 1.01 | 0.174 | 0.55 |

| Proprioceptive force sense | 6.07 ± 2.28 | 3.38 ± 2.02 | −2.69 ± 1.18 | 4.23 ± 1.48 | 2.00 ± 1.41 | −2.23 ± 1.09 | 0.31 | 0.40 |

| Joint range of motion | 91.38 ± 5.40 | 98.46 ± 6.78 | 7.07 ± 4.68 | 90.53 ± 5.5 | 96.3 ± 7.56 | 5.76 ± 4.32 | 0.46 | 0.29 |

| Joint position sense | ||||||||

| 30° flexion_Eyes open | 5.31 ± 2.56 | 2.61 ± 1.85 | −2.69 ± 1.93 | 5.54 ± 1.5 | 2.84 ± 1.72 | −2.69 ± 1.6 | 1 | 0 |

| 30° flexion_ Eyes closed | 5.15 ± 1.51 | 3 ± 1.29 | −2.15 ± 1.21 | 4.76 ± 1.96 | 2.46 ± 1.89 | −2.3 ± 1.31 | 0.75 | 0.12 |

| 60° flexion_Eyes open | 4.38 ± 2.21 | 2.46 ± 1.5 | −1.92 ± 1.32 | 4.53 ± 2.1 | 2.46 ± 1.33 | −2.07 ± 1.18 | 0.75 | 0.12 |

| 60° flexion_Eyes closed | 5.38 ± 1.55 | 2 ± 1 | −3.38 ± 1.44 | 4.38 ± 1.75 | 2.69 ± 1.49 | −1.69 ± 1.03 | 0.002 * | 1.35 |

| Quality of life | ||||||||

| Physical functioning | 89.23 ± 10.45 | 95.69 ± 11.62 | 6.46 ± 3.57 | 89.61 ± 6.81 | 92.53 ± 7.77 | 2.92 ± 2.13 | 0.006 * | 1.20 |

| Bodily pain | 77.53 ± 5.34 | 83 ± 4.35 | 5.46 ± 4.53 | 79.84 ± 3.26 | 84.84 ± 2.91 | 5 ± 3.65 | 0.778 | 0.11 |

| Physical role limitations | 76 ± 7.77 | 84 ± 8.61 | 8.07 ± 7.27 | 81.07 ± 3.45 | 87.07 ± 4.29 | 6 ± 3.89 | 0.373 | 0.36 |

| Emotional role limitations | 85.3 ± 5.34 | 91.46 ± 7.41 | 6.15 ± 4.96 | 84.38 ± 3.92 | 88.92 ± 4.31 | 4.53 ± 2.72 | 0.314 | 0.41 |

| Mental health | 70.84 ± 5.33 | 77.23 ± 4.18 | 6.38 ± 3.9 | 67.76 ± 3.65 | 72.3 ± 3.83 | 4.53 ± 3.04 | 0.191 | 0.53 |

| Social functioning | 84.23 ± 4.02 | 89.76 ± 4.83 | 5.53 ± 2.69 | 89.53 ± 4.4 | 94 ± 5.61 | 4.46 ± 1.94 | 0.254 | 0.46 |

| Energy/vitality | 61.23 ± 4.22 | 65.76 ± 4 | 4.53 ± 2.14 | 66.61 ± 4.21 | 69.23 ± 4.24 | 2.61 ± 1.44 | 0.013 * | 1.05 |

| General health perceptions | 71.46 ± 6.05 | 76.46 ± 4.17 | 5 ± 3.71 | 70.3 ± 3.52 | 74.07 ± 3.42 | 3.76 ± 2.74 | 0.347 | 0.38 |

| SF-36 Total | 615.84 ± 28.41 | 663.46 ± 29.37 | 47.61 ± 13.41 | 629.15 ± 13.42 | 663 ± 13.87 | 33.84 ± 10.49 | 0.456 | 1.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arabacı, E.; Okuyucu, K.; Erbahçeci, F. Kinesiology Taping in Grade I–II Meniscus Injuries: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. Medicina 2026, 62, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010097

Arabacı E, Okuyucu K, Erbahçeci F. Kinesiology Taping in Grade I–II Meniscus Injuries: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleArabacı, Eren, Kübra Okuyucu, and Fatih Erbahçeci. 2026. "Kinesiology Taping in Grade I–II Meniscus Injuries: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial" Medicina 62, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010097

APA StyleArabacı, E., Okuyucu, K., & Erbahçeci, F. (2026). Kinesiology Taping in Grade I–II Meniscus Injuries: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. Medicina, 62(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010097