Prognostic Value of Treatment-Related Body Composition Changes in Metastatic NSCLC Receiving Nivolumab

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

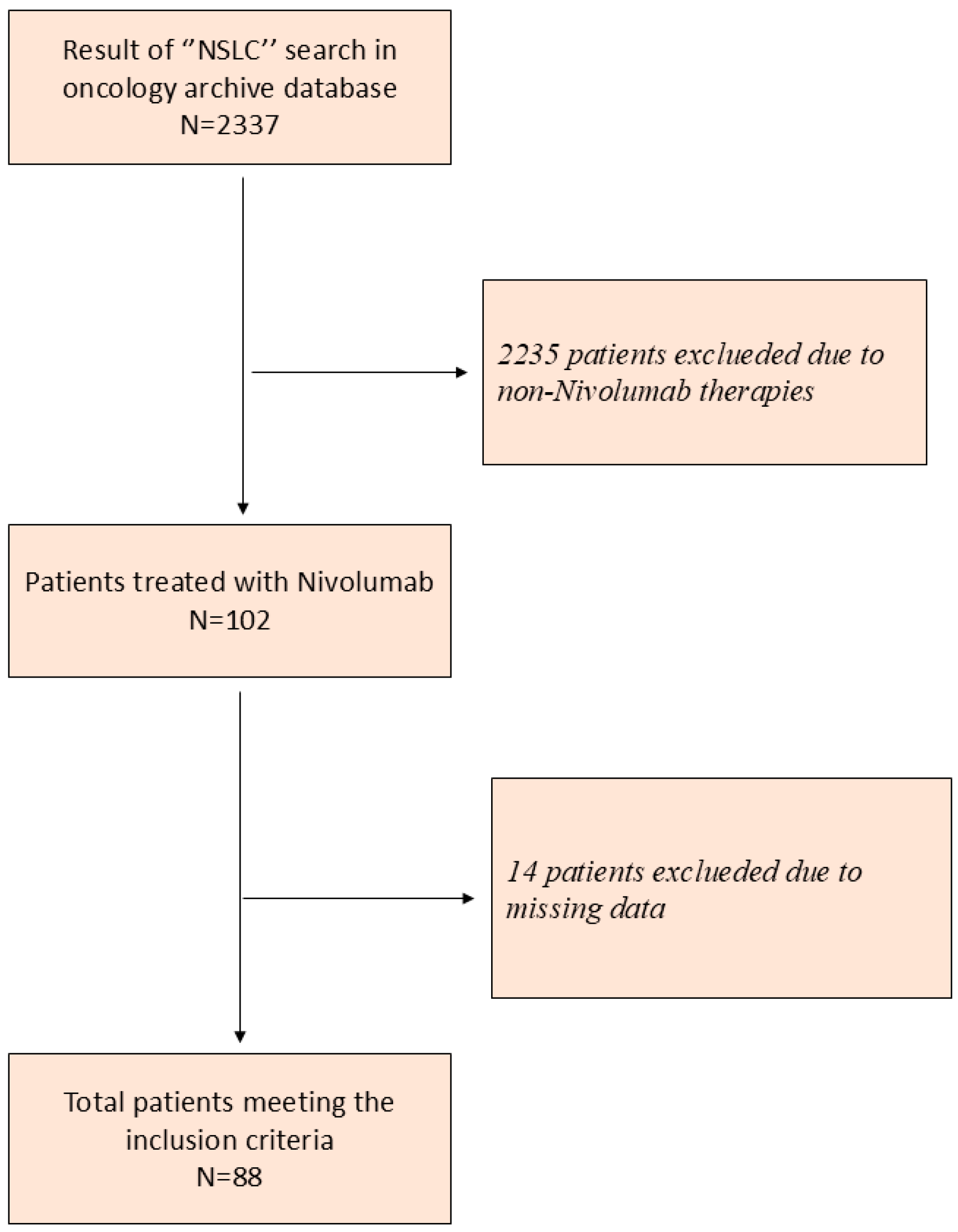

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. PET/CT Imaging Protocol

2.3. Body Composition and Laboratory Measurements

2.4. Endpoints

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Treatment Response and Survival Outcomes

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passaro, A.; Brahmer, J.; Antonia, S.; Mok, T.; Peters, S. Managing resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer: Treatment and novel strategies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baracos, V.E.; Martin, L.; Korc, M.; Guttridge, D.C.; Fearon, K.C. Cancer-associated cachexia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shachar, S.S.; Williams, G.R.; Muss, H.B.; Nishijima, T.F. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in adults with solid tumours: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 57, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Sayer, A.A. Sarcopenia. Lancet 2019, 393, 2636–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Birdsell, L.; MacDonald, N.; Reiman, T.; Clandinin, M.T.; McCargar, L.J.; Murphy, R.; Ghosh, S.; Sawyer, M.B.; Baracos, V.E. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, S.; Ihara, S.; Tanaka, T.; Komuta, K. Sarcopenia and visceral adiposity did not affect efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy for pretreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. World J. Oncol. 2020, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, M.; Martin, L.; Ghosh, S.; Field, C.J.; Lehner, R.; Baracos, V.E.; Mazurak, V.C. Subcutaneous adiposity is an independent predictor of mortality in cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, S.; Matsumoto, Y.; Toyozumi, T.; Otsuka, R.; Shiraishi, T.; Morishita, H.; Makiyama, T.; Nishioka, Y.; Yamada, M.; Hirata, A. High Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Radiodensity Predicts Poor Prognosis in Patients With Gastric Cancer. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 2024, 4, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, L.E.; Ní Bhuachalla, É.B.; Power, D.G.; Cushen, S.J.; James, K.; Ryan, A.M. Loss of skeletal muscle during systemic chemotherapy is prognostic of poor survival in patients with foregut cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Cui, J.; Li, W. CT-based muscle and adipose measurements predict prognosis in patients with digestive system malignancy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortellini, A.; Bozzetti, F.; Palumbo, P.; Brocco, D.; Di Marino, P.; Tinari, N.; De Tursi, M.; Agostinelli, V.; Patruno, L.; Valdesi, C. Weighing the role of skeletal muscle mass and muscle density in cancer patients receiving PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors: A multicenter real-life study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuno, H.; Nishioka, N.; Yamada, T.; Kunimatsu, Y.; Yoshimura, A.; Hirai, S.; Futamura, S.; Masui, T.; Egami, M.; Chihara, Y. The Significance of Longitudinal Psoas Muscle Loss in Predicting the Maintenance Efficacy of Durvalumab Treatment Following Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Ren, Y.; Liu, J.; Lv, S.; He, P.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chang, J.; Luo, D. Sarcopenia was a poor prognostic predictor for patients with advanced lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 900823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, F.; Zhu, F.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L. Predictive impact of sarcopenia in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A retrospective study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, S.; Ihara, S.; Komuta, K. Sarcopenia and visceral adiposity are not independent prognostic markers for extensive disease of small-cell lung cancer: A single-centered retrospective cohort study. World J. Oncol. 2020, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, M.; Wagner, E.F. Mechanisms of metabolic dysfunction in cancer-associated cachexia. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argilés, J.M.; Busquets, S.; Stemmler, B.; López-Soriano, F.J. Cancer cachexia: Understanding the molecular basis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Sun, Y.; van Dijk, D.P.; Deng, M.; Brecheisen, R.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Q.; Olde Damink, S.M.; Rensen, S.S. Loss of Skeletal Muscle Mass Is Associated with Reduced Cytotoxic T Cell Abundance and Poor Survival in Advanced Lung Cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2025, 16, e70063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkus, J.A.; Celi, F.S. The role of adipose tissue in cancer-associated cachexia. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lv, K.; Ge, R.; Xie, X. Prognostic value of body adipose tissue parameters in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1557726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenuta, M.; Gelibter, A.; Pandozzi, C.; Sirgiovanni, G.; Campolo, F.; Venneri, M.A.; Caponnetto, S.; Cortesi, E.; Marchetti, P.; Isidori, A.M. Impact of sarcopenia and inflammation on patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NCSCL) treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs): A prospective study. Cancers 2021, 13, 6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, M., Jr.; Olivan, M.; Alcantara, P.; Sandoval, R.; Peres, S.; Neves, R.; Silverio, R.; Maximiano, L.; Otoch, J.; Seelaender, M. Adipose tissue-derived factors as potential biomarkers in cachectic cancer patients. Cytokine 2013, 61, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Yu, J.; Li, W.; Luo, J.; Deng, Q.; Chen, B.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, C. Prognostic value of inflammatory and nutritional indexes among advanced NSCLC patients receiving PD-1 inhibitor therapy. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2023, 50, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Non-Sarcopenic (n = 58) | Sarcopenic (n = 30) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61 (58–63) | 65 (60–69) | 0.004 |

| Gender, male | 51 (87.9%) | 27 (90.0%) | 0.772 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.43 (22.15–28.19) | 25.66 (22.77–29.75) | 0.503 |

| Smoking status | 0.809 | ||

| Current smoker | 19 (36.5%) | 11 (39.3%) | |

| Former smoker | 33 (63.5%) | 17 (60.7%) | |

| ECOG ≥ 1 | 28/55 (50.9%) | 17/29 (58.6%) | 0.500 |

| CCI ≥ 4 | 35 (60.3%) | 12 (40.0%) | 0.070 |

| Histology, non-squamous | 35 (60.3%) | 18 (60.0%) | 0.975 |

| PD-L1 negative | 31 (60.8%) | 12 (46.2%) | 0.221 |

| Treatment line (2nd vs. ≥3rd) | 40 (69.0%) vs. 18 (31.0%) | 23 (76.7%) vs. 7 (23.3%) | 0.448 |

| De novo metastasis | 35 (62.5%) | 19 (63.3%) | 0.939 |

| Number of metastases ≥ 4 | 21 (36.8%) | 19 (63.3%) | 0.018 |

| Liver metastasis | 8 (14.0%) | 9 (30.0%) | 0.074 |

| Bone metastasis | 24 (42.1%) | 13 (43.3%) | 0.912 |

| Brain metastasis | 13 (23.2%) | 10 (33.3%) | 0.312 |

| Adrenal metastasis | 12 (21.1%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.624 |

| PMI (baseline), cm2/m2 | 6.08 (5.26–6.99) | 4.48 (4.06–5.83) | <0.001 |

| SMI (baseline), cm2/m2 | 56.99 (52.34–62.73) | 41.73 (37.90–48.20) | <0.001 |

| IMAC (baseline) | −0.251 (−0.296−0.206) | −0.224 (−0.642–0.184) | 0.048 |

| SFD (baseline) HU | −36.7 (−40.0–−33.4) | −31.9 (−38.4–−25.0) | <0.001 |

| ΔPMI | 4.60 (−4.40–13.22) | 17.53 (1.83–24.02) | 0.250 |

| ΔSMI | 2.61 (−2.65–8.53) | 12.22 (−9.72–28.95) | 0.078 |

| ΔIMAC | −3.28 (−36.99–19.69) | −0.29 (−51.95–−19.02) | 0.905 |

| ΔPNI | 7.45 (−8.60–−14.29) | −6.65 (−16.31–6.62) | 0.012 |

| ΔSFD | −36.8 (−40.92–−32.7) | −34.4 (−39.1–−30.1) | 0.278 |

| Variable | Non-Sarcopenic (n = 58) | Sarcopenic (n = 30) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORR, n (%) | 31 (53.4%) | 10 (33.3%) | 0.073 |

| DCR, n (%) | 35 (60.3%) | 14 (46.7%) | 0.221 |

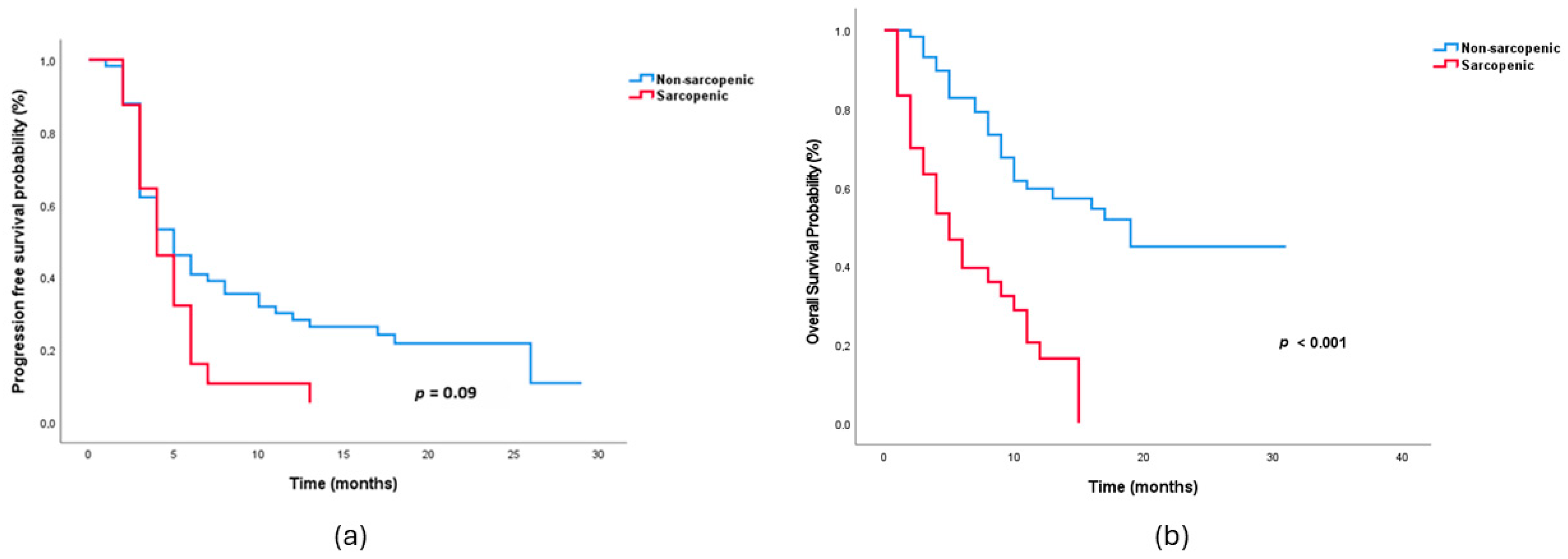

| Median PFS, months (95% CI) | 5.0 (3.2–6.8) | 4.0 (2.7–5.3) | 0.09 |

| Median OS, months (95% CI) | 19.0 (11.6–26.4) | 5.0 (2.8–7.3) | <0.001 |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age, >65 | 2.04 | 1.15–3.60 | 0.01 | 1.52 | 0.59–3.89 | 0.38 |

| Gender, male | 1.07 | 0.45–2.51 | 0.87 | |||

| Current smoker | 1.00 | 0.55–1.82 | 0.98 | |||

| BMI ≥ 25 | 1.28 | 0.73–2.23 | 0.37 | |||

| CCI ≥ 4 | 2.23 | 1.27–3.90 | 0.005 | 2.11 | 0.96–4.59 | 0.06 |

| ECOG ≥ 1 | 1.02 | 0.58–1.79 | 0.93 | |||

| Prior thoracic RT | 1.22 | 0.70–2.12 | 0.47 | |||

| PD-L1 status < 1 | 1.54 | 0.86–2.76 | 0.14 | |||

| De novo metastasis | 1.08 | 0.61–1.92 | 0.69 | |||

| Number of metastasis ≥ 4 | 1.20 | 0.69–2.07 | 0.50 | |||

| Liver metastasis | 2.14 | 1.14–3.99 | 0.01 | 1.86 | 0.80–4.30 | 0.14 |

| Bone metastasis | 0.87 | 0.50–1.51 | 0.62 | |||

| Brain metastasis | 1.48 | 0.82–2.65 | 0.18 | |||

| Adrenal metastasis | 1.02 | 0.52–2.00 | 0.93 | |||

| PNI, low | 1.68 | 0.97–2.92 | 0.06 | 1.71 | 0.81–3.59 | 0.15 |

| PMI, low | 2.11 | 1.21–3.67 | 0.008 | 1.02 | 0.38–2.70 | 0.96 |

| SMI, low | 1.35 | 0.78–2.33 | 0.28 | |||

| SFD, low | 1.63 | 0.94–2.82 | 0.07 | 1.05 | 0.42–2.61 | 0.90 |

| Sarcopenia, present | 3.60 | 2.02–6.4 | <0.001 | 1.09 | 0.41–2.88 | 0.85 |

| IMAC, low | 1.19 | 0.69–2.06 | 0.51 | |||

| ΔPMI, low | 2.48 | 1.27–4.83 | 0.007 | 1.28 | 0.55–2.97 | 0.55 |

| ΔIMAC, low | 1.09 | 0.56–2.10 | 0.79 | |||

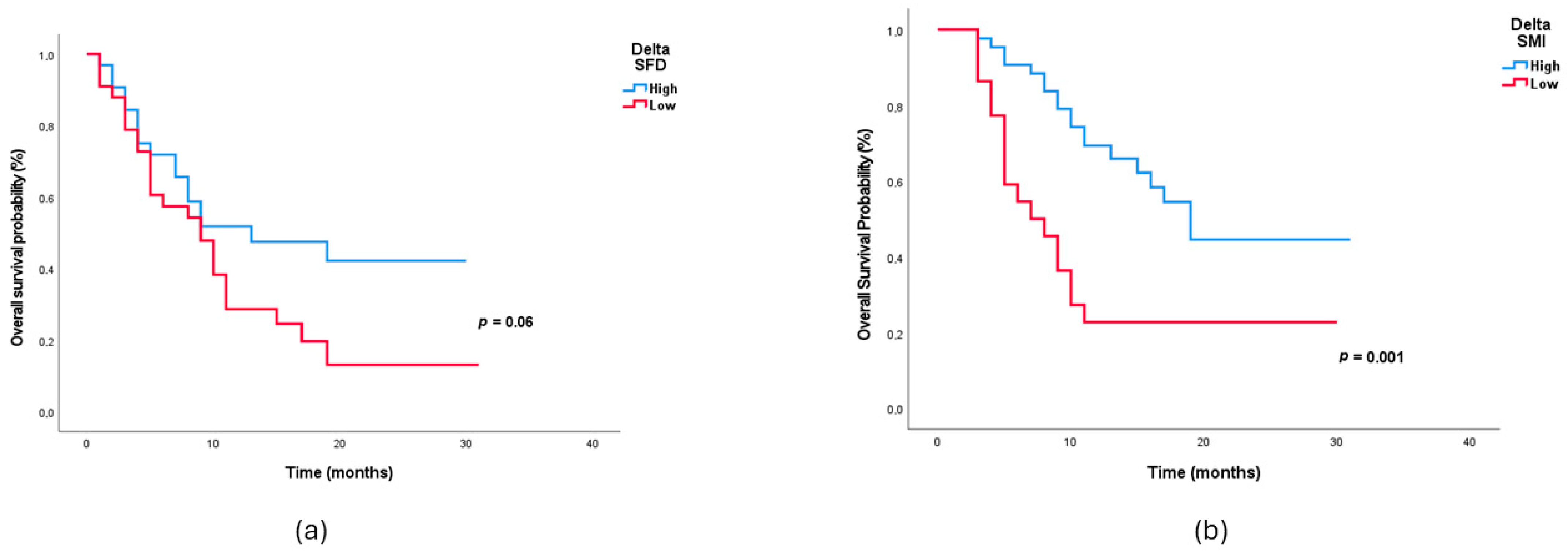

| ΔSMI, low | 2.78 | 1.43–5.38 | 0.002 | 3.39 | 1.52–7.56 | 0.003 |

| ΔPNI, low | 2.52 | 1.39–4.58 | 0.002 | 1.94 | 0.83–4.50 | 0.12 |

| ΔSFD, low | 2.35 | 0.90–6.11 | 0.07 | 2.45 | 1.14–5.28 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kocaaslan, E.; Güren, A.K.; Akagündüz, F.; Demirel, A.; Tunç, M.A.; Paçacı, B.; Ağyol, Y.; Erel, P.; Çelebi, A.; Işık, S.; et al. Prognostic Value of Treatment-Related Body Composition Changes in Metastatic NSCLC Receiving Nivolumab. Medicina 2026, 62, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010098

Kocaaslan E, Güren AK, Akagündüz F, Demirel A, Tunç MA, Paçacı B, Ağyol Y, Erel P, Çelebi A, Işık S, et al. Prognostic Value of Treatment-Related Body Composition Changes in Metastatic NSCLC Receiving Nivolumab. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleKocaaslan, Erkam, Ali Kaan Güren, Fırat Akagündüz, Ahmet Demirel, Mustafa Alperen Tunç, Burak Paçacı, Yeşim Ağyol, Pınar Erel, Abdüssamed Çelebi, Selver Işık, and et al. 2026. "Prognostic Value of Treatment-Related Body Composition Changes in Metastatic NSCLC Receiving Nivolumab" Medicina 62, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010098

APA StyleKocaaslan, E., Güren, A. K., Akagündüz, F., Demirel, A., Tunç, M. A., Paçacı, B., Ağyol, Y., Erel, P., Çelebi, A., Işık, S., Çoban, E., Demircan, N. C., Özgüven, S., Balaban Genç, Z. C., Majidova, N., Sever, N., Sarı, M., Köstek, O., & Bayoğlu, İ. V. (2026). Prognostic Value of Treatment-Related Body Composition Changes in Metastatic NSCLC Receiving Nivolumab. Medicina, 62(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010098