Lichtenstein Repair and Intersurgeon Variations: A Textbook Review and Multicenter Surgeon Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Wide subaponeurotic dissection, including distal to the pubic tubercle, to allow for adequate mesh overlap;

- Identification and preservation of all three inguinal nerves (IIN, IHN, GbGFN) to avoid entrapment neuropathy, chronic pain, and unnecessary dysesthesias;

- Assessment of the femoral canal for a potential coexisting femoral hernia in every case;

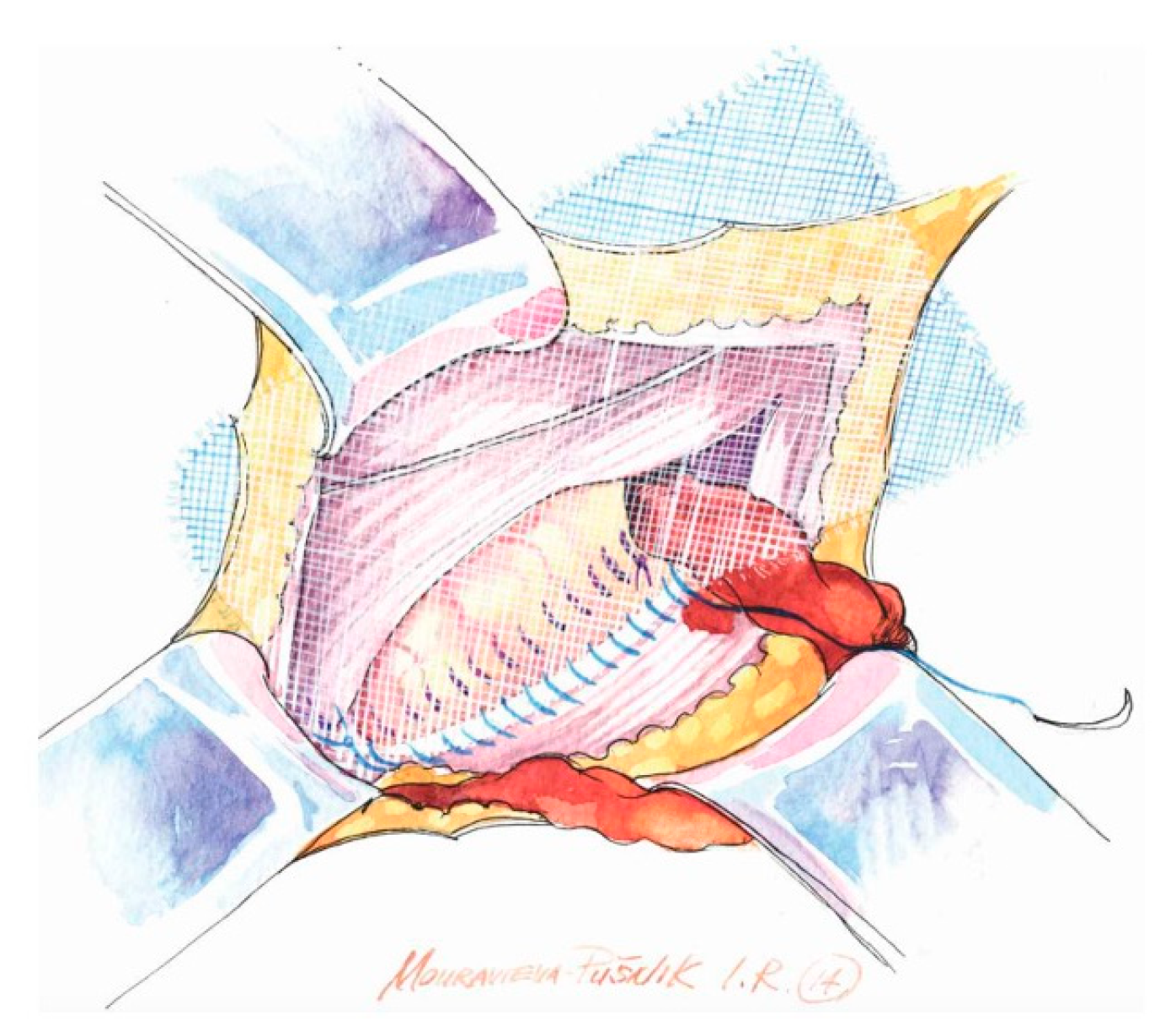

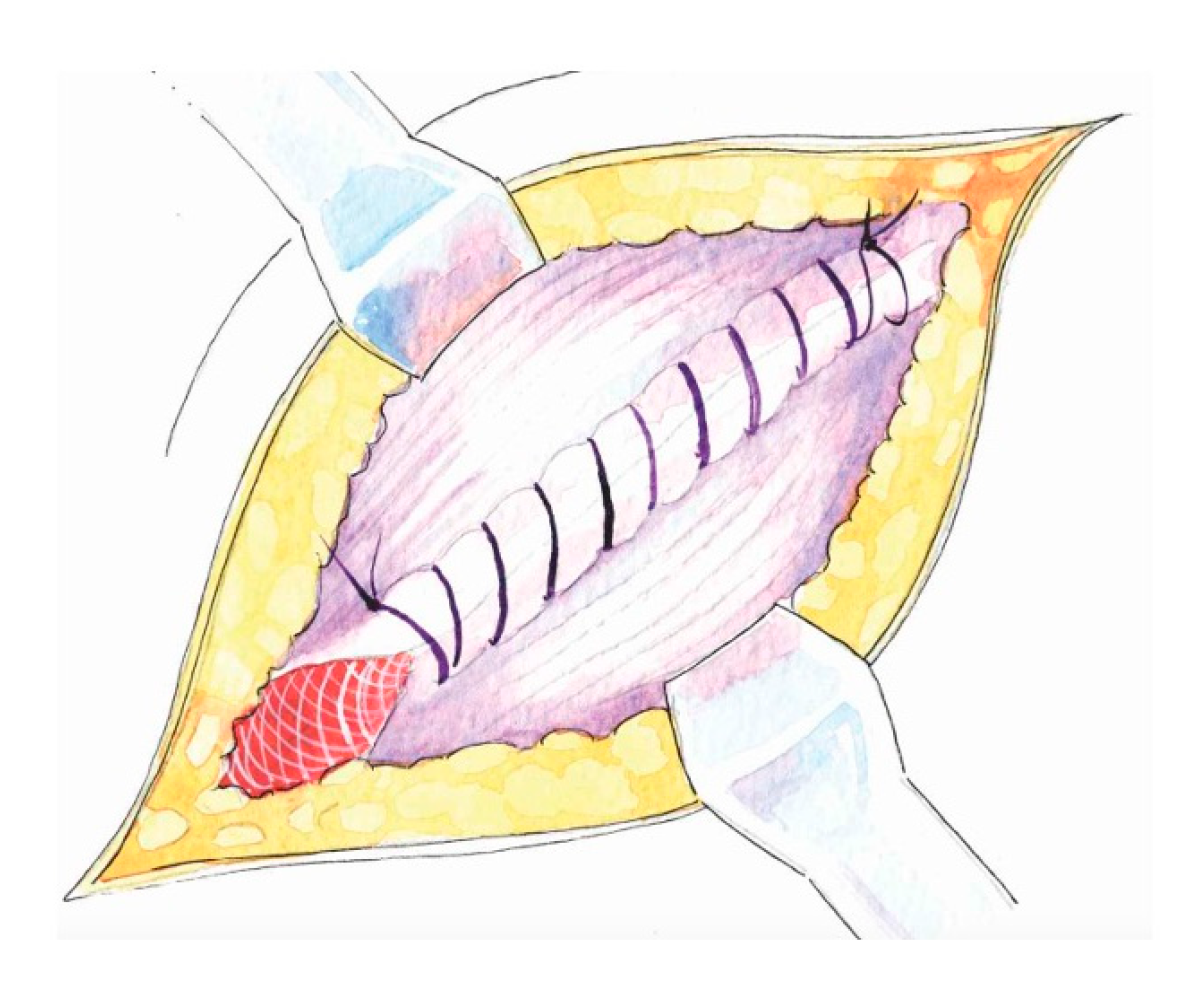

- Preparation of the inguinal floor, with suture imbrication for direct hernias, and, in indirect hernias, Marcy-type suturing to cranially reposition the deep ring;

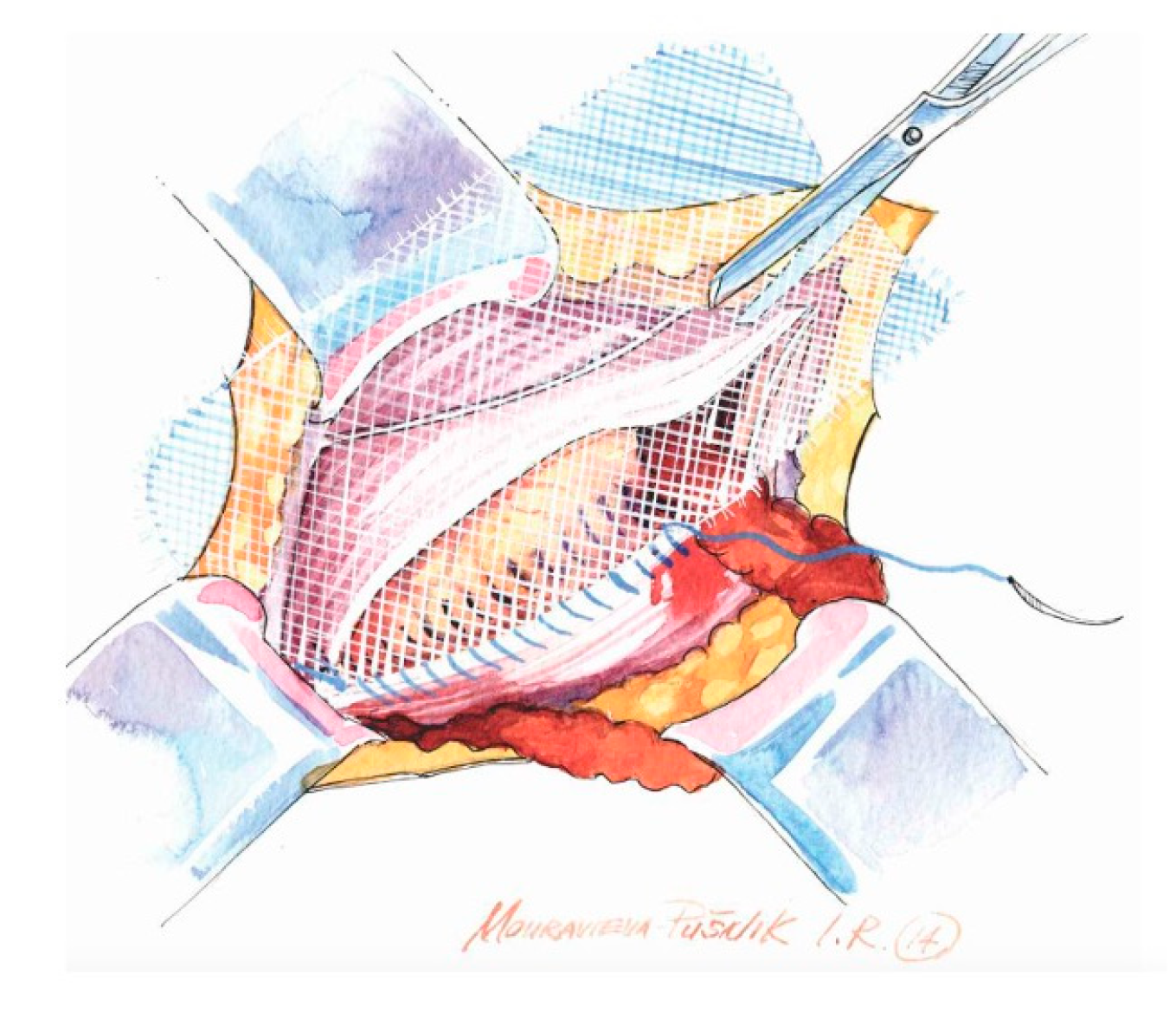

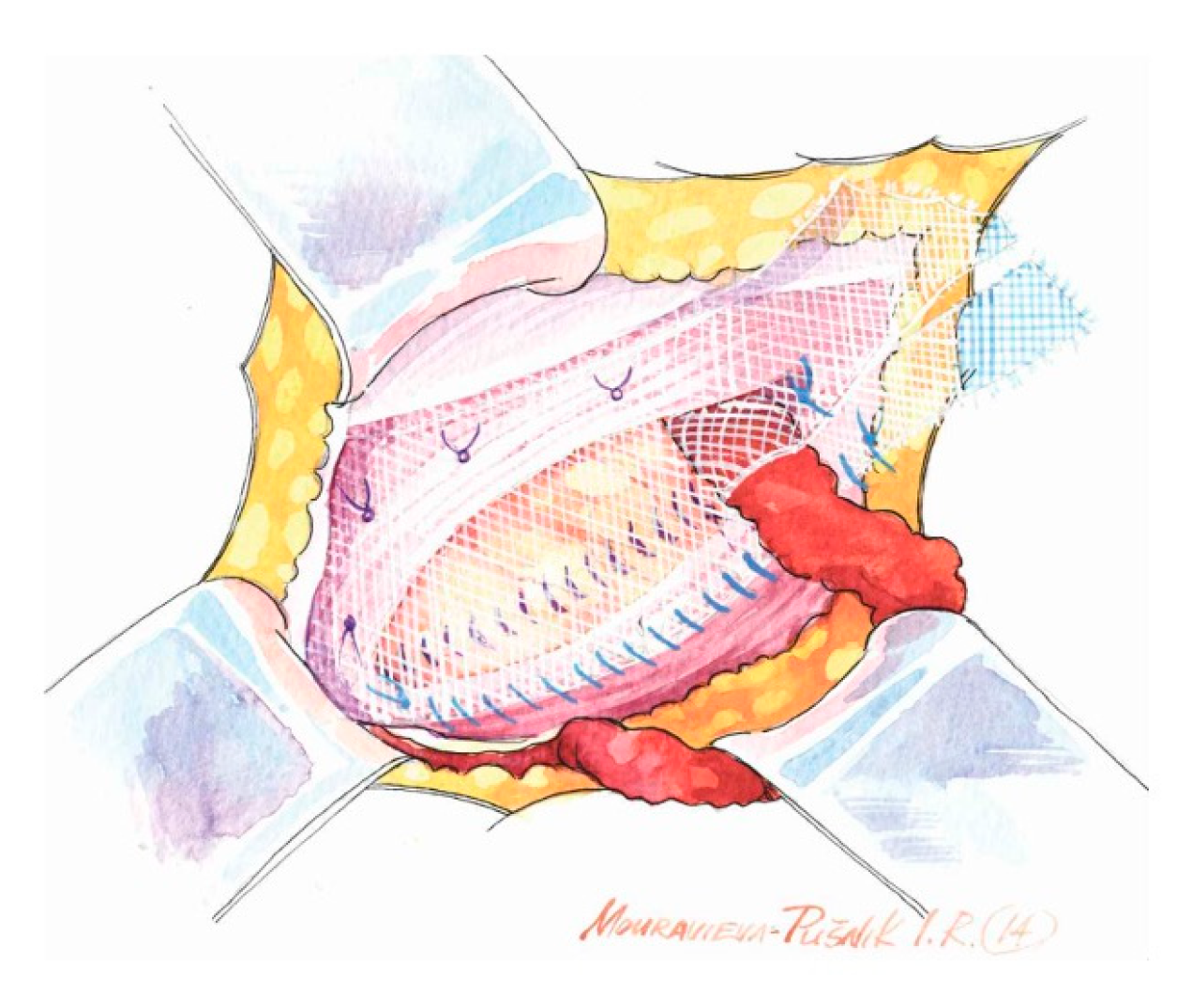

- Use of a sufficiently large mesh (≥12 × 8 cm) with ≥2 cm overlap beyond the pubic tubercle to avoid direct space recurrence;

- Preservation of mesh tails with 4–5 cm of cephalad extension to account for coexisting interstitial or low-lying Spigelian hernias; overlapping the medial tail over the lateral with secure fixation of both tails to the inguinal ligament to create the mesh internal ring; consider fixation to Cooper’s ligament when femoral hernia is present.

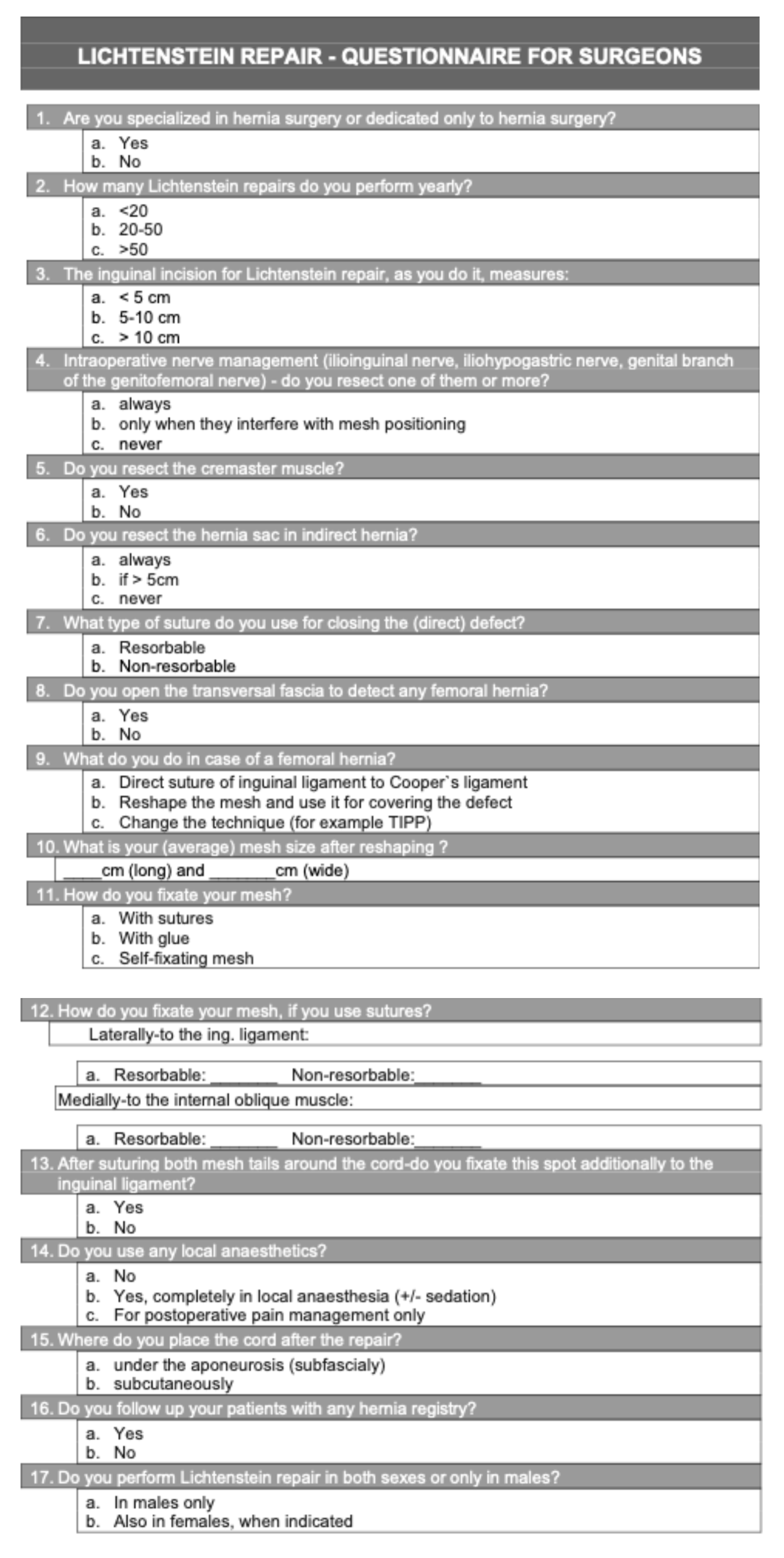

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kingsnorth, A.; LeBlanc, K. Hernias: Inguinal and incisional. Lancet 2003, 362, 1561–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbons, R.J.; Ramanan, B.; Arya, S.; Turner, S.A.; Li, X.; Gibbs, J.O.; Reda, D.J. Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial of a nonoperative strategy (watchful waiting) for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M.P.; Aufenacker, T.; Bay-Nielsen, M.; Bouillot, J.L.; Campanelli, G.; Conze, J.; de Lange, D.; Fortelny, R.; Heikkinen, T.; Kingsnorth, A.; et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 2009, 343–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuijs, S.W.; Rosman, C. Long-term outcome after randomizing prolene hernia system, mesh plug repair and Lichtenstein for inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 2015, 19, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, I.L.; Shulman, A.G.; Amid, P.K.; Montllor, M.M. The tension-free hernioplasty. Am. J. Surg. 1989, 157, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, P.K. Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty: Its inception, evolution, and principles. Hernia 2004, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsnorth, A.; Gingell-Littlejohn, M.; Nienhuijs, S.; Schüle, S.; Appel, P.; Ziprin, P.; Eklund, A.; Miserez, M.; Smeds, S. Randomized controlled multicenter international clinical trial of self-gripping Parietex ProGrip polyester mesh versus lightweight polypropylene mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: Interim results at 3 months. Hernia 2012, 16, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay-Nielsen, M.; Kehlet, H. Anaesthesia and post-operative morbidity after elective groin hernia repair: A nation-wide study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2008, 52, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsnorth, A.N.; Britton, B.J.; Morris, P.J. Recurrent inguinal hernia after local anaesthetic repair. Br. J. Surg. 1981, 68, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrett, P.E.M. Day care surgery. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2001, 18, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillcutt, S.D.; Clarke, M.G.; Kingsnorth, A.N. Cost-effectiveness of groin hernia surgery in the Western Region of Ghana. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsnorth, A.N.; Clarke, M.G.; Shillcutt, S.D. Public health and policy issues of hernia surgery in Africa. World J. Surg. 2009, 33, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, M.; Encke, A. Repair procedures in surgery of inguinal hernia in their historical evolution. Zentralbl. Chir. 1993, 118, 780–787. [Google Scholar]

- Chastan, P. Tension-free inguinal hernia repair: A retrospective study of 3000 cases in one center. Int. Surg. 2005, 90, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.C.; Morrison, J. State of the art: Open mesh-based inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 2019, 23, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendavid, R.; Abrahamson, J.; Arregui, M.E.; Flament, J.B.; Phillips, E.H. (Eds.) Abdominal Wall Hernias: Principles and Management; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, E.C.; Zollinger, R.M., Jr. Zollinger’s Atlas of Surgical Operations, 10th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2016; Chapter 107; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, C.M., Jr.; Beauchamp, R.D.; Evers, B.M.; Mattox, K.L. (Eds.) Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice, 20th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1100–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, W.W.; Cobb, W.S.; Adrales, G.L. (Eds.) Textbook of Hernia, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Brunicardi, F.C.; Andersen, D.K.; Billiar, T.R.; Dunn, D.L.; Hunter, J.G.; Kao, L.S.; Matthews, J.B.; Pollock, R.E. (Eds.) Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery, 11th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1626–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Campanelli, G. (Ed.) The Art of Hernia Surgery: A Step-by-Step Guide, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, R.; Stechemesser, B.; Reinpold, W. (Eds.) Hernienschule: Kompakt-Konkret-Komplex, 1st ed.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 111–119. ISBN 978-3-11-051937-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R.; Renaud, M.C.; Huguet, F.; André, T.; Duguet, A.; Steichen, O. Discrepancies in medical textbooks and their impact on medical school students. Bull. Cancer 2021, 108, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.; Morris, A.; Marais, B. Medical student use of digital learning resources. Clin. Teach. 2018, 15, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köckerling, F.; Maneck, M.; Günster, C.; Adolf, D.; Hukauf, M. Comparing routine administrative data with registry data for assessing quality of hospital care in patients with inguinal hernia. Hernia 2020, 24, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köckerling, F.; Sheen, A.J.; Berrevoet, F.; Campanelli, G.; Cuccurullo, D.; Fortelny, R.; Friis-Andersen, H.; Gillion, J.F.; Gorjanc, J.; Kopelman, D.; et al. The reality of general surgery training and increased complexity of abdominal wall hernia surgery. Hernia 2019, 23, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallouris, A.; Kakagia, D.; Yiacoumettis, A.; Vasilakaki, T.; Drougou, A.; Lambropoulou, M.; Simopoulos, C.; Tsaroucha, A.K. Histological Comparison of the Human Trunk Skin Creases: The Role of the Elastic Fiber Component. Eplasty 2016, 16, e15. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, M.U.; Mjöbo, H.N.; Nielsen, P.R.; Rudin, A. Prediction of postoperative pain: A systematic review of predictive experimental pain studies. Anesthesiology 2010, 112, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinpold, W.; Schroeder, A.D.; Schroeder, M.; Berger, C.; Rohr, M.; Wehrenberg, U. Retroperitoneal anatomy of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve: Consequences for prevention and treatment of chronic inguinodynia. Hernia 2015, 19, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, P.K. Causes, prevention, and surgical treatment of postherniorrhaphy neuropathic inguinodynia: Triple neurectomy with proximal end implantation. Hernia 2004, 8, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, P.K.; Hiatt, J.R. New understanding of the causes and surgical treatment of postherniorrhaphy inguinodynia and orchalgia. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2007, 205, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeds, S.; Löfström, L.; Eriksson, O. Influence of nerve identification and the resection of nerves “at risk” on postoperative pain in open inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 2010, 14, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, S.; Rotondi, F.; Di Giorgio, A.; Fumagalli, U.; Salzano, A.; Di Miceli, D.; Ridolfini, M.P.; Sgagari, A.; Doglietto, G. Groin Pain Trial Group. Influence of preservation versus division of ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genital nerves during open mesh herniorrhaphy: Prospective multicentric study of chronic pain. Ann. Surg. 2006, 243, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.; Chen, C.-S.; Lee, H.-C.; Liang, H.; Kuo, L.; Wei, P.; Tam, K. Preservation versus division of ilioinguinal nerve on open mesh repair of inguinal hernia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J. Surg. 2012, 36, 2311–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedberg, S.G.; Broome, A.E.; Gullmo, A. Ligation of the hernial sac? Surg. Clin. N. Am. 1984, 64, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Matsugami, T.; Chiba, T. The origin of sensory innervation of the peritoneum in the rat. Anat. Embryol. 2002, 205, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stylianidis, G.; Haapamäki, M.M.; Sund, M.; Nilsson, E.; Nordin, P. Management of the hernial sac in inguinal hernia repair. Br. J. Surg. 2010, 97, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson, N.; Gunnarsson, U.; Nordin, P.; Smedberg, S.; Hedberg, M.; Sandblom, G. Reoperation for persistent pain after groin hernia surgery: A population-based study. Hernia 2015, 19, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouldice, E.B. The Shouldice repair for groin hernias. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 83, 1163–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gols, J.; Berkmans, E.; Timmers, M.; Vanluyten, C.; Ceulemans, L.J.; Deferm, N.P. Extended Lichtenstein Repair for an Additional Femoral Canal Hernia. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, S.; DeLozier, K.R.; Erdemir, A.; Derwin, K.A. Clinically relevant mechanical testing of hernia graft constructs. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 41, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyhe, D.; Cobb, W.; Lecuivre, J.; Alves, A.; Ladet, S.; Lomanto, D.; Bayon, Y. Large pore size and controlled mesh elongation are relevant predictors for mesh integration quality and low shrinkage—Systematic analysis of key parameters of meshes in a novel minipig hernia model. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 22, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seker, D.; Oztuna, D.; Kulacoglu, H.; Genc, Y.; Akcil, M. Mesh size in Lichtenstein repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the importance of mesh size. Hernia 2013, 17, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calomino, N.; Poto, G.E.; Carbone, L.; Micheletti, G.; Gjoka, M.; Giovine, G.; Sepe, B.; Bagnacci, G.; Piccioni, S.A.; Cuomo, R.; et al. Weighing the benefits: Exploring the differential effects of light-weight and heavy-weight polypropylene meshes in inguinal hernia repair in a retrospective cohort study. Am. J. Surg. 2024, 238, 115950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.L.; Waydia, S. A systematic review of randomised control trials assessing mesh fixation in open inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 2014, 18, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Fuchs, C.; Angst, E.; Vorburger, S.; Helbling, C.; Candinas, D.; Schlumpf, R. Prospective randomized trial comparing sutured with sutureless mesh fixation for Lichtenstein hernia repair: Long-term results. Hernia 2012, 16, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaans, W.A.R.; Verhagen, T.; Wouters, L.; Loos, M.J.A.; Roumen, R.M.H.; Scheltinga, M.R.M. Groin Pain Characteristics and Recurrence Rates: Three-year Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Self-gripping Progrip Mesh and Sutured Polypropylene Mesh for Open Inguinal Hernia Repair. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanelli, G.; Pascual, M.H.; Hoeferlin, A.; Rosenberg, J.; Champault, G.; Kingsnorth, A.; Miserez, M. Randomized, controlled, blinded trial of Tisseel/Tissucol for mesh fixation in patients undergoing Lichtenstein technique for primary inguinal hernia repair: Results of the TIMELI trial. Ann. Surg. 2012, 255, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorjanc, J. The Shouldice repair–experience with first 50 patients. Zdr. Vestn. (Slov. Med. J.) 2011, 80, 668–675. [Google Scholar]

- Damous, S.H.B.; Damous, L.L.; Miranda, J.S.; Montero, E.F.S.; Birolini, C.; Utiyama, E.M. Could polypropylene mesh impair male reproductive organs? Experimental study with different methods of implantation. Hernia 2020, 24, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andresen, K.; Kroon, L.; Holmberg, H.; Nordin, P.; Rosenberg, J.; Öberg, S.; de la Croix, H. Risk of reoperation after TEP, TAPP, and Lichtenstein repair for primary groin hernia: A register-based cohort study across two nations. Hernia 2025, 29, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, P.; van der Linden, W. Volume of procedures and risk of recurrence after repair of groin hernia: National register study. BMJ 2008, 336, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.; Haapaniemi, S. The Swedish hernia register: An eight year experience. Hernia 2000, 4, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay-Nielsen, M.; Kehlet, H.; Strand, L.; Malmstrøm, J.; Andersen, F.H.; Wara, P.; Juul, P.; Callesen, T.; Danish Hernia Database Collaboration. Quality assessment of 26,304 herniorrhaphies in Denmark: A prospective nationwide study. Lancet 2001, 358, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The HerniaSurge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 2018, 22, 1–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question According to Questionnaire | Answer | No. of Surgeons (Total 70) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caseload of LR per surgeon/year | <30 | n = 19 | 27% |

| 30–50 | n = 37 | 53% | |

| >50 | n = 14 | 20% | |

| Hernia sub-specialization | Yes | n = 10 | 14% |

| No | n = 60 | 86% | |

| Skin incision size | <5 cm | n = 15 | 21% |

| 5–10 cm | n = 47 | 68% | |

| >10 cm | n = 8 | 11% | |

| Surgical management of sensory nerves | Never resect | n = 18 | 25% |

| Resect when needed | n = 50 | 72% | |

| Always resect | n = 2 | 3% | |

| Cremaster muscle resection | Yes, always | n = 1 | 1% |

| Yes, if necessary | n = 4 | 5% | |

| No | n = 65 | 94% | |

| Hernia sac resection (indirect) | Always resect | n = 8 | 11% |

| Resect when >5 cm | n = 53 | 77% | |

| Never resect | n = 9 | 12% | |

| Sutures of the inguinal floor | Yes | n = 59 | 84% |

| No | n = 11 | 16% | |

| Checking for femoral hernia | Yes | n = 22 | 32% |

| No | n = 48 | 68% | |

| Synchronous femoral repair | Suture to Cooper’s ligament | n = 51 | 73% |

| Reshape mesh and cover defect | n = 13 | 19% | |

| Switch to TIPP technique | n = 6 | 8% | |

| Final mesh size after shaping | 15 × 10 cm | n = 30 | 43% |

| 12 × 7 cm | n = 22 | 32% | |

| 10 × 6 cm | n = 18 | 25% | |

| How to fixate the mesh | Sutures | n = 53 | 76% |

| Glue | n = 9 | 13% | |

| Self-gripping mesh | n = 8 | 11% | |

| Suture fixation | Laterally absorbable | n = 4 | 5% |

| Laterally non-absorbable | n = 66 | 95% | |

| Medially absorbable | n = 64 | 92% | |

| Medially non-absorbable | n = 6 | 8% | |

| Suture of the mesh tails | Yes | n = 54 | 77% |

| No | n = 16 | 23% | |

| The role of local anesthesia (LA) | None | n = 40 | 57% |

| Op. in LA only | n = 5 | 7% | |

| For postop. pain control | n = 25 | 36% | |

| Spermatic cord position | Subaponeurotically | n = 59 | 84% |

| Subcutaneously | n = 11 | 16% | |

| Cooperation with hernia registry | Yes | n = 8 | 11% |

| No | n = 62 | 89% | |

| Use of Lichtenstein Repair in females | In males only | n = 66 | 94% |

| Also in females (when indicated) | n = 4 | 6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gorjanc, J.; Chen, D.C.; Kingsnorth, A.; Mittermair, R. Lichtenstein Repair and Intersurgeon Variations: A Textbook Review and Multicenter Surgeon Survey. Medicina 2026, 62, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010079

Gorjanc J, Chen DC, Kingsnorth A, Mittermair R. Lichtenstein Repair and Intersurgeon Variations: A Textbook Review and Multicenter Surgeon Survey. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010079

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorjanc, Jurij, David C. Chen, Andrew Kingsnorth, and Reinhard Mittermair. 2026. "Lichtenstein Repair and Intersurgeon Variations: A Textbook Review and Multicenter Surgeon Survey" Medicina 62, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010079

APA StyleGorjanc, J., Chen, D. C., Kingsnorth, A., & Mittermair, R. (2026). Lichtenstein Repair and Intersurgeon Variations: A Textbook Review and Multicenter Surgeon Survey. Medicina, 62(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010079