Interdependent Effect of Intrinsic Risk Factors on Non-Contact Lower Limb Injuries in Male Football Players: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

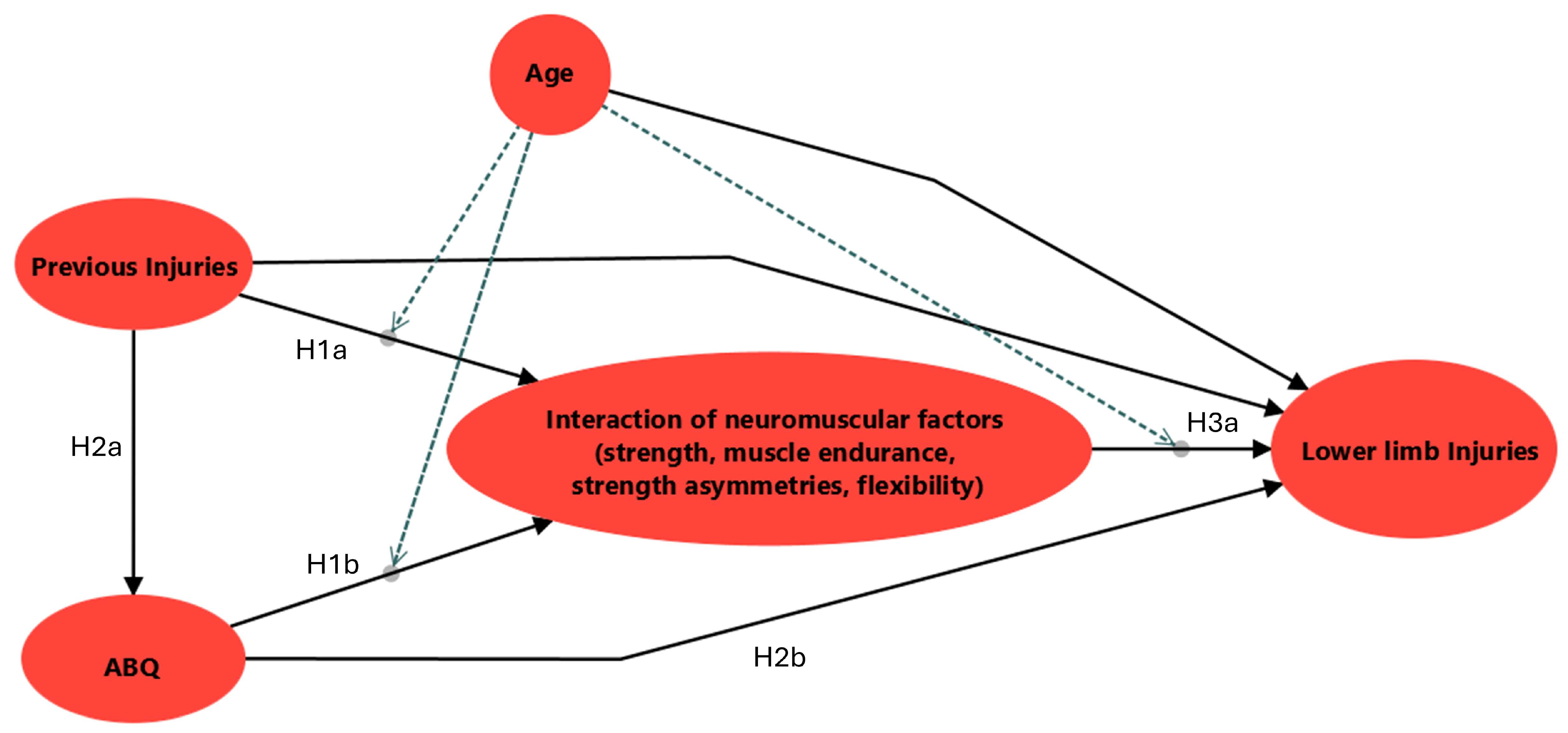

Structural Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

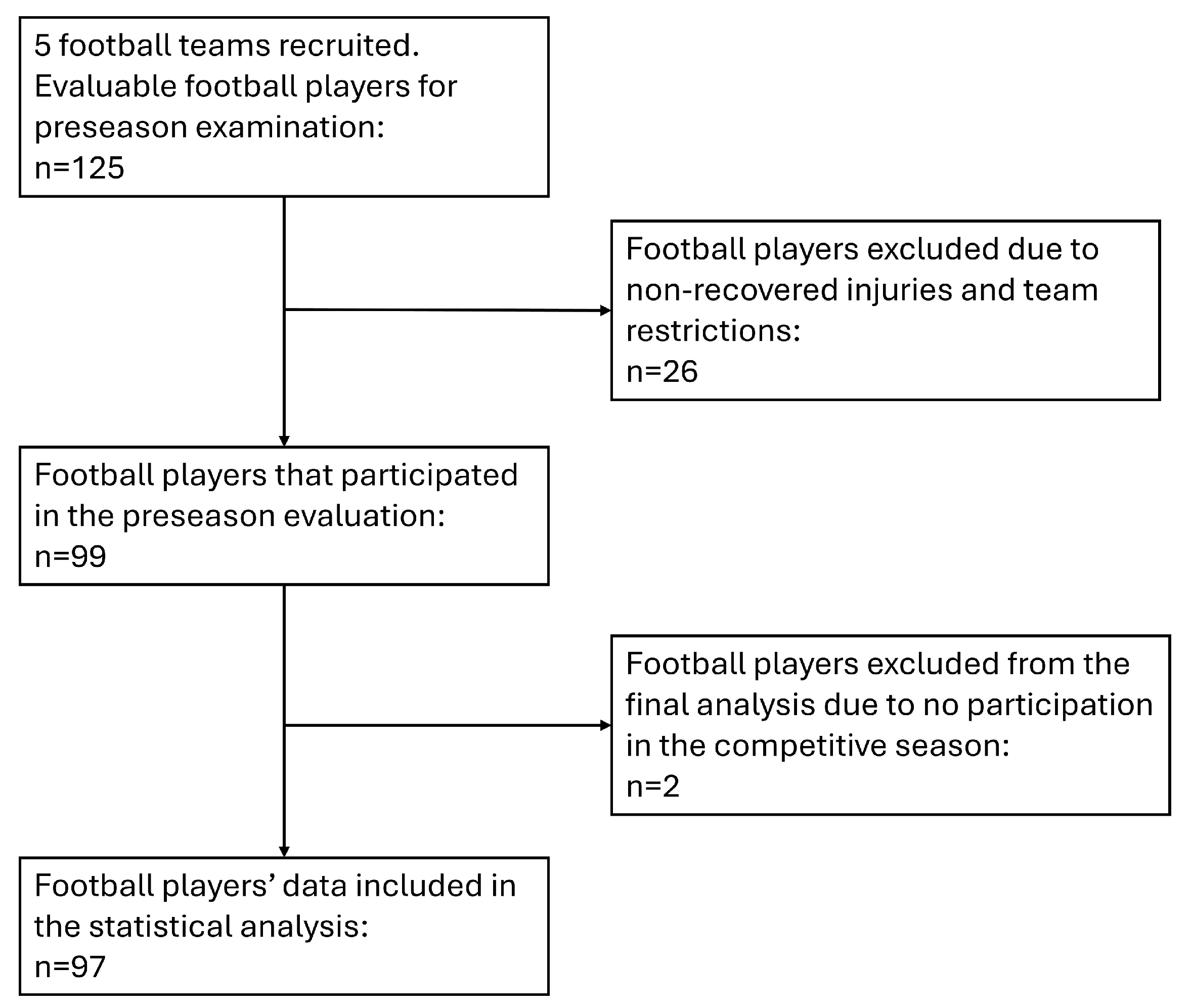

2.2. Participants

2.3. Preseason Data Collection

2.3.1. Survey Questionnaires

2.3.2. Screening Tests

2.4. Injury Surveillance

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives of Preseason Screening Data

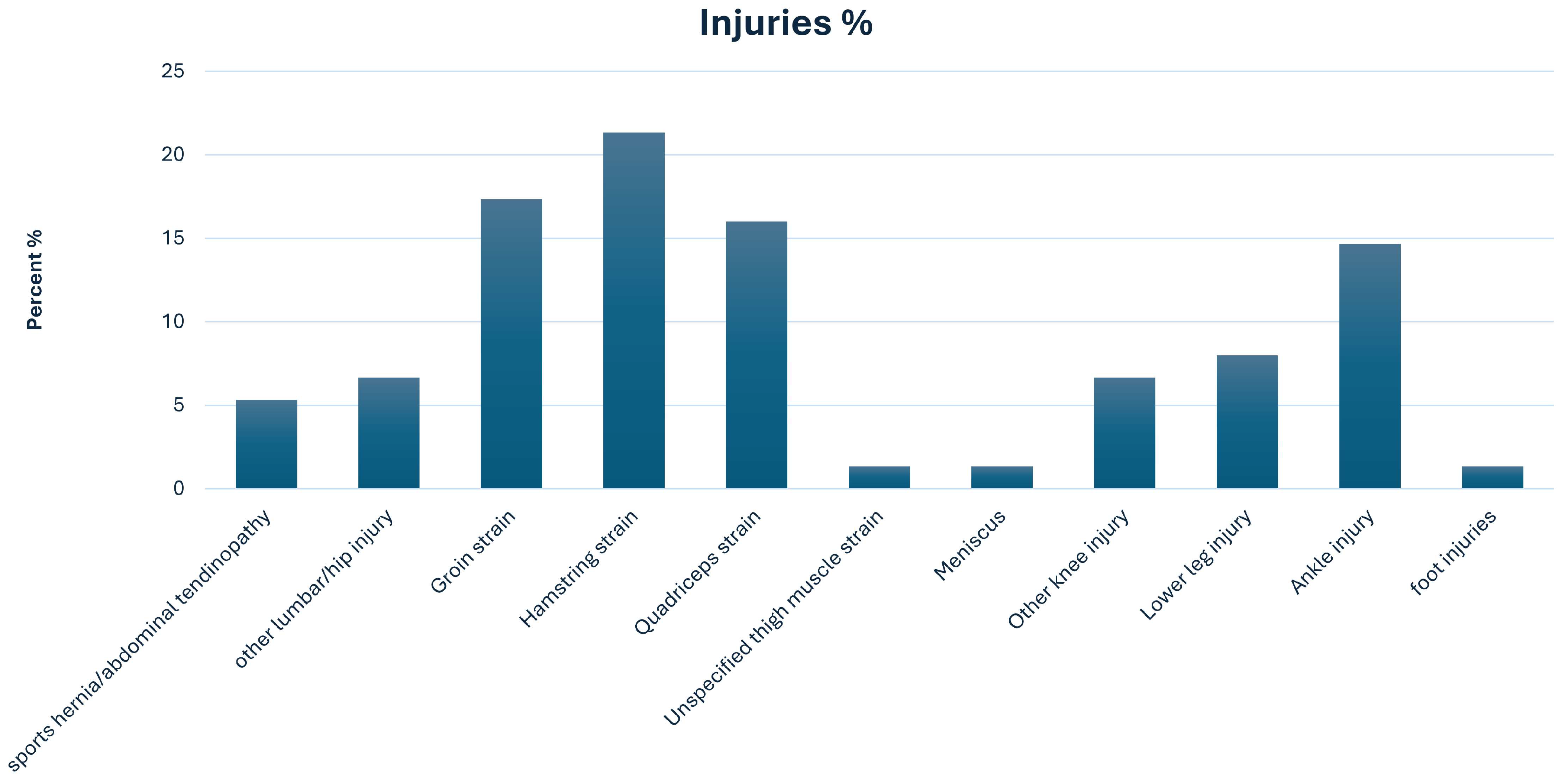

3.2. Prospective Injury Data

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.4. PLS-SEM of Risk Factors Interrelationships That Affect the Frequency of Non-Contact LL Injuries

3.4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

3.4.2. Structural Model Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fares, M.Y.; Stewart, K.; McBride, M.; Maclean, J. Lower Limb Injuries in an English Professional Football Club: Injury Analysis and Recommendations for Prevention. Phys. Sportsmed. 2023, 51, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Valenciano, A.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Garcia-Gómez, A.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; De Ste Croix, M.; Myer, G.D.; Ayala, F. Epidemiology of Injuries in Professional Football: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liveris, N.I.; Tsarbou, C.; Papageorgiou, G.; Tsepis, E.; Fousekis, K.; Kvist, J.; Xergia, S.A. The Complex Interrelationships of the Risk Factors Leading to Hamstring Injury and Implications for Injury Prevention: A Group Model Building Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarbou, C.; Liveris, N.I.; Xergia, S.A.; Papageorgiou, G.; Kvist, J.; Tsepis, E. ACL Injury Etiology in Its Context: A Systems Thinking, Group Model Building Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hootman, J.M.; Dick, R.; Agel, J. Epidemiology of Collegiate Injuries for 15 Sports: Summary and Recommendations for Injury Prevention Initiatives. J. Athl. Train. 2007, 42, 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett, T.E.; Myer, G.D.; Ford, K.R.; Paterno, M.V.; Quatman, C.E. Mechanisms, Prediction, and Prevention of ACL Injuries: Cut Risk with Three Sharpened and Validated Tools. J. Orthop. Res. 2016, 34, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Tanaka, M.; Shida, M. Intrinsic Risk Factors of Lateral Ankle Sprain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Health 2015, 8, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniar, N.; Carmichael, D.S.; Hickey, J.T.; Timmins, R.G.; Jose, A.J.S.; Dickson, J.; Opar, D. Incidence and Prevalence of Hamstring Injuries in Field-Based Team Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 5952 Injuries from over 7 Million Exposure Hours. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.; Bourne, M.N.; van Dyk, N.; Pizzari, T. Recalibrating the Risk of Hamstring Strain Injury (HSI): A 2020 Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Risk Factors for Index and Recurrent Hamstring Strain Injury in Sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liveris, N.I.; Papageorgiou, G.; Tsepis, E.; Fousekis, K.; Tsarbou, C.; Xergia, S.A. Towards the Development of a System Dynamics Model for the Prediction of Lower Extremity Injuries. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2023, 16, 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittencourt, N.F.N.N.; Meeuwisse, W.H.; Mendonça, L.D.; Nettel-Aguirre, A.; Ocarino, J.M.; Fonseca, S.T. Complex Systems Approach for Sports Injuries: Moving from Risk Factor Identification to Injury Pattern Recognition—Narrative Review and New Concept. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windt, J.; Gabbett, T.J. How Do Training and Competition Workloads Relate to Injury? The Workload—Injury Aetiology Model. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, S.T.; Souza, T.R.; Verhagen, E.; van Emmerik, R.; Bittencourt, N.F.N.; Mendonça, L.D.M.; Andrade, A.G.P.; Resende, R.A.; Ocarino, J.M. Sports Injury Forecasting and Complexity: A Synergetic Approach. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1757–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, J.D.; Cormack, S.J.; Whiteley, R.; Williams, M.D.; Timmins, R.G.; Opar, D.A. Modeling the Risk of Team Sport Injuries: A Narrative Review of Different Statistical Approaches. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Valenciano, A.; Ayala, F.; Puerta, J.M.; De Ste Croix, M.B.A.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; Hernandez-Sanchez, S.; Ruiz-Perez, I.; Myer, G.D. A Preventive Model for Muscle Injuries: A Novel Approach Based on Learning Algorithms. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddy, J.D.; Shield, A.J.; Maniar, N.; Williams, M.D.; Duhig, S.; Timmins, R.G.; Hickey, J.; Bourne, M.N.; Opar, D.A. Predictive Modeling of Hamstring Strain Injuries in Elite Australian Footballers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, F.; López-Valenciano, A.; Gámez Martín, J.A.; De Ste Croix, M.; Vera-Garcia, F.; García-Vaquero, M.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Myer, G. A Preventive Model for Hamstring Injuries in Professional Soccer: Learning Algorithms. Int. J. Sports Med. 2019, 40, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, A.; Thompson, J.; Nielsen, R.O.; Read, G.J.M.; Salmon, P.M. Towards a Complex Systems Approach in Sports Injury Research: Simulating Running-Related Injury Development with Agent-Based Modelling. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Zajkowski, R. An Integrated Structural Equation Modelling and Machine Learning Framework for Measurement Scale Evaluation—Application to Voluntary Turnover Intentions. Appl. Math 2025, 5, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Shirkey, G.; John, R.; Wu, S.R.; Park, H.; Shao, C. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Ecological Studies: An Updated Review. Ecol. Process 2016, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for Building and Testing Behavioral Causal Theory: When to Choose It and How to Use It. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, A.; Johnson, U. Psychological Factors as Predictors of Injuries among Senior Soccer Players. A Prospective Study. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2010, 9, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fulton, J.; Wright, K.; Kelly, M.; Zebrosky, B.; Zanis, M.; Drvol, C.; Butler, R. Injury Risk Is Altered by Previous Injury: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Presentation of Causative Neuromuscular Factors. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 9, 583–595. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, R.; Clarsen, B.; Derman, W.; Dvorak, J.; Emery, C.A.; Finch, C.F.; Hägglund, M.; Junge, A.; Kemp, S.; Khan, K.M.; et al. International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement: Methods for Recording and Reporting of Epidemiological Data on Injury and Illness in Sport 2020 (Including STROBE Extension for Sport Injury and Illness Surveillance (STROBE-SIIS)). Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-5443-9640-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liveris, N.I.; Tsarbou, C.; Papageorgiou, G.; Tsepis, E.; Fousekis, K.; Xergia, S.A. A Field-Based Screening Protocol for Hamstring Injury Risk in Football Players: Evaluating Its Functionality Using Exploratory Factor Analysis. Sports 2025, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarbou, C.; Liveris, N.I.; Xergia, S.A.; Papageorgiou, G.; Sideris, V.; Giakas, G.; Tsepis, E. Evaluating the Functionality of a Field-Based Test Battery for the Identification of Risk for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: An Exploratory Factor Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.W.; Ekstrand, J.; Junge, A.; Andersen, T.E.; Bahr, R.; Dvorak, J.; Hägglund, M.; McCrory, P.; Meeuwisse, W.H. Consensus Statement on Injury Definitions and Data Collection Procedures in Studies of Football (Soccer) Injuries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, K.; Rossi, M.T.; Parkkari, J.; Heinonen, A.; Steffen, K.; Myklebust, G.; Krosshaug, T.; Vasankari, T.; Kannus, P.; Avela, J.; et al. Predictors of Lower Extremity Injuries in Team Sports (PROFITS-Study): A Study Protocol. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2015, 1, e000076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markati, A.; Psychountaki, M.; Karteroliotis, K. Athlete Burnout Questionnaire: Validity and Reliability in a Greek Population. In Proceedings of the ΙV European Congress of Methodology; European Association of Methodology: Berlin, Germany, 2010; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Markati, A.; Psychountaki, M.; Kingston, K.; Karteroliotis, K.; Apostolidis, N. Psychological and Situational Determinants of Burnout in Adolescent Athletes. Int. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 17, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, A.; de Baranda, P.S.; Ayala, F.; Croix, M.D.S.; Santonja-Medina, F. Assessment of the Range of Movement of the Lower Limb in Sport: Advantages of the ROM-SPORT I Battery. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 7606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.S.; Quinn, R.O.; Whiteman, C.T.; Williams, J.D.; Young, C.R. Concurrent Validity of Four Clinical Tests Used to Measure Hamstring Flexibility. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, V.; Ayala, F.; Fernandez-Fernandez, J.; Vera-Garcia, F.J. Descriptive Profile of Hip Range of Motion in Elite Tennis Players. Phys. Ther. Sport 2016, 19, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeler, J.; Anderson, J.E. Reliability of the Thomas Test for Assessing Range of Motion about the Hip. Phys. Ther. Sport 2007, 8, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeler, J.; Anderson, J.E. Reliability of the Ely’s Test for Assessing Rectus Femoris Muscle Flexibility and Joint Range of Motion. J. Orthop. Res. 2008, 26, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, K.; Talbot, R.; Wajswelner, H.; Techovanich, W.; Kelly, D. Intra-Rater and Inter-Rater Reliability of a Weight-Bearing Lunge Measure of Ankle Dorsiflexion. Aust. J. Physiother. 1998, 44, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powden, C.J.; Hoch, J.M.; Hoch, M.C. Reliability and Minimal Detectable Change of the Weight-Bearing Lunge Test: A Systematic Review. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, L.; Witvrouw, E.; Vanden Bossche, L.; De Clercq, D. Lower Eccentric Hamstring Strength and Single Leg Hop for Distance Predict Hamstring Injury in PETE Students. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2015, 15, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteley, R.; van Dyk, N.; Wangensteen, A.; Hansen, C. Clinical Implications from Daily Physiotherapy Examination of 131 Acute Hamstring Injuries and Their Association with Running Speed and Rehabilitation Progression. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorborg, K.; Petersen, J.; Magnusson, S.P.; Hölmich, P. Clinical Assessment of Hip Strength Using a Hand-Held Dynamometer Is Reliable. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.M.; McCartney, C.N.; Sweeney, R.S.; Palimenio, M.R.; Grindstaff, T.L. Hand-Held Dynamometer Positioning Impacts Discomfort During Quadriceps Strength Testing: A Validity and Reliability Study. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 10, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stark, T.; Walker, B.; Phillips, J.K.; Fejer, R.; Beck, R. Hand-Held Dynamometry Correlation With the Gold Standard Isokinetic Dynamometry: A Systematic Review. PM&R 2011, 3, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazett-Jones, D.M.; Cobb, S.C.; Joshi, M.N.; Cashin, S.E.; Earl, J.E. Normalizing Hip Muscle Strength: Establishing Body-Size-Independent Measurements. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorborg, K.; Couppé, C.; Petersen, J.; Magnusson, S.P.; Hölmich, P. Eccentric Hip Adduction and Abduction Strength in Elite Soccer Players and Matched Controls: A Cross-Sectional Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokeler, A.; Welling, W.; Zaffagnini, S.; Seil, R.; Padua, D. Development of a Test Battery to Enhance Safe Return to Sports after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, M.; Duchesne, E.; Bernier, J.; Blanchette, P.; Langlois, D.; Hébert, L.J. What Is Known About Muscle Strength Reference Values for Adults Measured by Hand-Held Dynamometry: A Scoping Review. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2022, 4, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarbou, C.; Liveris, N.I.; Xergia, S.A.; Tsekoura, M.; Fousekis, K.; Tsepis, E. Pre-Season ACL Risk Classification of Professional and Semi-Professional Football Players, via a Proof-of-Concept Test Battery. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.T.; Shultz, S.J.; Schmitz, R.J.; Perrin, D.H. Triple-Hop Distance as a Valid Predictor of Lower Limb Strength and Power. J. Athl. Train. 2008, 43, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.; Squillante, A.; Dawes, J. The Single Leg Triple Hop for Distance Test. Strength. Cond. J. 2017, 39, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterno, M.V.; Huang, B.; Thomas, S.; Hewett, T.E.; Schmitt, L.C. Clinical Factors That Predict a Second ACL Injury After ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport: Preliminary Development of a Clinical Decision Algorithm. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleksy, Ł.; Królikowska, A.; Mika, A.; Kuchciak, M.; Szymczyk, D.; Rzepko, M.; Bril, G.; Prill, R.; Stolarczyk, A.; Reichert, P. A Compound Hop Index for Assessing Soccer Players’ Performance. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freckleton, G.; Cook, J.; Pizzari, T. The Predictive Validity of a Single Leg Bridge Test for Hamstring Injuries in Australian Rules Football Players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Blaiser, C.; De Ridder, R.; Willems, T.; Danneels, L.; Vanden Bossche, L.; Palmans, T.; Roosen, P. Evaluating Abdominal Core Muscle Fatigue: Assessment of the Validity and Reliability of the Prone Bridging Test. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill, S.M.; Childs, A.; Liebenson, C. Endurance Times for Low Back Stabilization Exercises: Clinical Targets for Testing and Training from a Normal Database. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999, 80, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coorevits, P.; Danneels, L.; Cambier, D.; Ramon, H.; Vanderstraeten, G. Assessment of the Validity of the Biering-Sørensen Test for Measuring Back Muscle Fatigue Based on EMG Median Frequency Characteristics of Back and Hip Muscles. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2008, 18, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fousekis, K.; Tsepis, E.; Vagenas, G. Multivariate Isokinetic Strength Asymmetries of the Knee and Ankle in Professional Soccer Players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2010, 50, 465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, M.W. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. J. Black Psychol. 2018, 44, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Global Edition; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780135153093. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin, C.J.; Happell, B. On Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Review of Recent Evidence, an Assessment of Current Practice, and Recommendations for Future Use. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Winship, C.; Zhuo, X. Interpreting T-Statistics Under Publication Bias: Rough Rules of Thumb. J. Quant. Criminol. 2020, 36, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfirrmann, D.; Herbst, M.; Ingelfinger, P.; Simon, P.; Tug, S. Analysis of Injury Incidences in Male Professional Adult and Elite Youth Soccer Players: A Systematic Review. J. Athl. Train. 2016, 51, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassis, K.; Misiris, I.; Plakias, S.; Siouras, A.; Spanos, S.; Giamouridis, E.; Dimitriadis, Z.; Tsaopoulos, D.; Poulis, I.A. Injury Pattern According to Player Position in Male Amateur Football Players in Greece: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helme, M.; Tee, J.; Emmonds, S.; Low, C. Does Lower-Limb Asymmetry Increase Injury Risk in Sport? A Systematic Review. Phys. Ther. Sport 2021, 49, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.; Bourne, M.N.; Pizzari, T. Isokinetic Strength Assessment Offers Limited Predictive Validity for Detecting Risk of Future Hamstring Strain in Sport: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Taunton, J.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, N.; Warburton, D.E.R. Association between Inter-Limb Asymmetries in Lower-Limb Functional Performance and Sport Injury: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madruga-Parera, M.; Dos’Santos, T.; Bishop, C.; Turner, A.; Blanco, D.; Beltran-Garrido, V.; Moreno-Pérez, V.; Romero-Rodríguez, D. Assessing Inter-Limb Asymmetries in Soccer Players: Magnitude, Direction and Association with Performance. J. Hum. Kinet. 2021, 79, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.; Welde, B.; Sagelv, E.H.; Heitmann, K.A.; Randers, M.B.; Johansen, D.; Pettersen, S.A. Associations between Maximal Strength, Sprint, and Jump Height and Match Physical Performance in High-Level Female Football Players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, A.A.; Mohamed, N.A.; Hegazy, M.A. A Comparative Study of Core Musculature Endurance and Strength Between Soccer Players with and Without Lower Extremity Sprain and Strain Injury. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 14, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areia, C.; Barreira, P.; Montanha, T.; Oliveira, J.; Ribeiro, F. Neuromuscular Changes in Football Players with Previous Hamstring Injury. Clin. Biomech. 2019, 69, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivarsson, A.; Johnson, U.; Andersen, M.B.; Tranaeus, U.; Stenling, A.; Lindwall, M. Psychosocial Factors and Sport Injuries: Meta-Analyses for Prediction and Prevention. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbett, T.J. The Training-Injury Prevention Paradox: Should Athletes Be Training Smarter and Harder? Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factors | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 22.16 ± 5.03 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.44 ± 7.71 |

| Height (cm) | 178.82 ± 6.27 |

| BMI | 23.25 ± 1.76 |

| Age started playing football | 7.75 ± 2.94 |

| Years playing in professional level | 3.79 ± 4.06 |

| Participation in matches the previous year | 19.26 ± 9.48 |

| Hours of training per day the previous year | 2.33 ± 0.64 |

| Days training per week the previous year | 5.53 ± 0.60 |

| Measurements | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Tests Description | Equipment/Variable | ||

| 1 | Anthropometric | Weight | Force platform (kg) | |

| Height | Measuring tape (cm) | |||

| Leg length | Measuring tape (cm) | |||

| Plantar length | Measuring tape (cm) | |||

| 2 | Flexibility | Hamstrings | Passive strain leg raise (supine position) | Inclinometer (°) |

| Iliopsoas | Thomas test (supine position) | Qualitative assessment pass/no pass | ||

| Rectus Femoris | Ely’s test (prone position) | Inclinometer (°) | ||

| Hip internal/external rotation | Hip internal/external ROM (prone position) | Inclinometer (°) | ||

| Ankle dorsiflexion | Weight-bearing lunge test (standing position) | Inclinometer (°) | ||

| 3 | Strength | Abductor | Side-lying position. Isometric test for approximately 5 s. | HHD (Nm/kg) |

| Hamstrings (Brake) | Prone position. Break test after approximately 3 s isometric contraction; 30° knee flexion. | HHD (Nm/kg) | ||

| Hamstring (Make) | Prone position 30° knee flexion. Isometric contraction for approximately 5 s. | HHD (Nm/kg) | ||

| Quadriceps | Isometric contraction. Sitting position with the use of a stabilization belt. | HHD (Nm/kg) | ||

| 4 | Functional and ballistic performance | Hop distance | Single-leg triple hop for distance (THD) Test | Hop distance (cm), max distance divided by athlete’s height (normative value) |

| 5 | Endurance | Abdominal | Prone Bridging Test | Stopwatch (maximum time in second) |

| Lateral abdominal | Side Bridging Test | Stopwatch (maximum time in second) | ||

| Back muscle | Biering–Sorensen test | Stopwatch (maximum time in second) | ||

| Hamstring | Single-leg hamstring bridge (SLHB). | Maximum repetitions | ||

| Measured Variables | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABQ | Emotional Physical Exhaustion | 1.00 | 3.20 | 1.65 | 0.48 | 0.89 | 0.48 |

| Reduced Sense of Accomplishment | 1.00 | 3.80 | 2.45 | 0.56 | −0.37 | 0.39 | |

| Devaluation | 1.00 | 4.33 | 1.34 | 0.63 | 2.67 | 7.84 | |

| Dominant lower limb | Leg Length D | 82.00 | 103.50 | 92.41 | 4.42 | 0.10 | −0.06 |

| Flexibility WBLT D | 24.00 | 51.50 | 37.04 | 5.43 | 0.22 | −0.12 | |

| Flexibility LSR D | 53.00 | 96.50 | 77.18 | 8.66 | −0.03 | −0.14 | |

| Flexibility Knee Flexion D | 120.00 | 165.00 | 143.60 | 7.73 | −0.08 | 0.85 | |

| Flexibility Hip Internal D | 11.00 | 53.00 | 29.32 | 7.86 | 0.33 | 0.24 | |

| Flexibility Hip External D | 27.50 | 75.50 | 47.46 | 8.94 | 0.33 | 0.65 | |

| Flexibility Thomas Test D (1 = negative, 2 = positive) | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.67 | 0.47 | −0.73 | −1.49 | |

| Strength Abductor D | 1.68 | 3.02 | 2.28 | 0.28 | 0.00 | −0.44 | |

| Strength HS Isometric (brake test) D | 1.12 | 2.37 | 1.61 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.34 | |

| Strength HS Isometric (make test) D | 1.00 | 2.21 | 1.49 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.98 | |

| Strength Quadriceps D | 1.85 | 4.30 | 3.04 | 0.46 | 0.01 | −0.18 | |

| THD D | 2.43 | 4.29 | 3.23 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.97 | |

| SLHB D | 10.00 | 60.00 | 32.77 | 9.99 | 0.13 | −0.10 | |

| Non-dominant lower limb | Leg Length ND | 82.00 | 104.50 | 92.51 | 4.43 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Flexibility WBLT ND | 23.00 | 55.00 | 37.47 | 5.62 | 0.03 | 0.23 | |

| Flexibility LSR ND | 51.50 | 97.00 | 78.71 | 8.74 | −0.18 | 0.00 | |

| Flexibility Knee Flexion ND | 121.00 | 160.00 | 143.98 | 8.20 | −0.40 | 0.40 | |

| Flexibility Hip Internal ND | 10.00 | 51.50 | 28.62 | 8.30 | 0.31 | 0.11 | |

| Flexibility Hip External ND | 26.00 | 67.50 | 48.73 | 8.89 | −0.04 | −0.52 | |

| Flexibility Thomas Test ND (1 = negative, 2 = positive) | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.69 | 0.46 | −0.84 | −1.33 | |

| Strength Abductor ND | 1.34 | 2.99 | 2.19 | 0.28 | −0.15 | 0.84 | |

| Strength HS Isometric (brake test) ND | 1.07 | 2.23 | 1.57 | 0.25 | 0.41 | −0.17 | |

| Strength HS Isometric (make test) ND | 1.07 | 1.98 | 1.46 | 0.19 | 0.18 | −0.40 | |

| Strength Quadriceps ND | 1.64 | 3.99 | 3.08 | 0.47 | −0.25 | −0.08 | |

| THD ND | 2.57 | 4.23 | 3.25 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.61 | |

| SLHB ND | 10.00 | 60.00 | 32.93 | 10.35 | 0.42 | −0.38 | |

| Asymmetries | Flexibility WBLT LS | 0.00 | 23.08 | 7.03 | 5.77 | 1.06 | 0.43 |

| Flexibility LSR LS | 0.00 | 17.83 | 5.55 | 4.22 | 1.08 | 0.52 | |

| Flexibility Knee Flexion LS | 0.00 | 11.68 | 2.95 | 2.64 | 1.31 | 1.46 | |

| Flexibility Hip Internal LS | 0.00 | 50.00 | 15.28 | 10.47 | 0.83 | 0.84 | |

| Flexibility Hip External LS | 0.98 | 40.59 | 12.32 | 8.08 | 1.06 | 1.70 | |

| Strength Abductors LS | 0.00 | 33.76 | 8.12 | 6.33 | 0.94 | 1.47 | |

| Strength HS Isometric (brake test) LS | 0.00 | 21.01 | 6.90 | 5.16 | 0.68 | −0.30 | |

| Strength HS Isometric (make test) LS | 0.14 | 21.29 | 5.65 | 4.43 | 1.10 | 1.17 | |

| Strength Quadriceps LS | 0.13 | 24.64 | 7.30 | 6.01 | 1.12 | 0.69 | |

| THD LS | 0.00 | 19.69 | 4.90 | 4.04 | 1.07 | 0.90 | |

| SLHB LS | 0.00 | 38.46 | 13.68 | 10.42 | 0.55 | −0.55 | |

| Core endurance | Prone Bridge | 49.00 | 380.00 | 175.40 | 76.12 | 0.84 | 0.11 |

| Side Bridge D | 47.00 | 190.00 | 90.10 | 28.71 | 0.98 | 1.03 | |

| Side Bridge ND | 45.00 | 168.00 | 89.61 | 27.73 | 0.57 | −0.55 | |

| Biering–Sorensen Test | 5.00 | 211.00 | 100.30 | 36.95 | 0.57 | 0.33 |

| Type of Injury | Frequency of Injuries (Injuries and Re-Injuries) | Re-Injuries | Percent (%) | Time Loss (Mean ± SD) | Injuries per 1000 Athlete-Hours Exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sports hernia/abdominal tendinopathy | 4 | 0 | 5.3 | 48.00 ± 30.53 | 0.10 |

| Other lumbar/hip injury | 5 | 0 | 6.7 | 8.00 ± 5.29 | 0.13 |

| Groin strain | 13 | 2 | 17.3 | 6.62 ± 6.25 | 0.34 |

| Hamstring strain | 16 | 2 | 21.3 | 13.31 ± 9.80 | 0.42 |

| Quadriceps strain | 12 | 1 | 16 | 13.00 ± 12.66 | 0.31 |

| Unspecified thigh muscle strain | 1 | 0 | 1.3 | 20.00 ± 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Meniscus | 1 | 0 | 1.3 | 60.00 ± 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Other knee injury | 5 | 0 | 6.7 | 15.00 ± 19.64 | 0.13 |

| Lower leg injury | 6 | 0 | 8 | 6.33 ± 4.85 | 0.16 |

| Ankle injury | 11 | 2 | 14.7 | 16.00 ± 20.99 | 0.29 |

| Foot injuries | 1 | 0 | 1.3 | 22.00 ± 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Total | 75 | 0 | 100 | 1.97 |

| Latent Factors | Measured Indicators | Convergent Validity | Internal Consistency Reliability | Discriminant Validity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha | Reliability pA | Composite Reliability pc | HTMT | ||

| >0.70 | >0.50 | 0.60–0.90 | 0.60–0.90 | 0.60–0.90 | <0.85 | ||

| ABQ | Devaluation | 0.753 | 0.606 | 0.674 | 0.676 | 0.822 | YES |

| Emotional Physical Exhaustion | 0.818 | ||||||

| Reduced Sense of Accomplishment | 0.763 | ||||||

| LL Strength Asymmetries | HS isometric (make test) Strength LS | 0.949 | 0.639 | 0.500 | 0.784 | 0.772 | YES |

| THD LS | 0.614 | ||||||

| Ballistic Function | QD Isometric Strength D | 0.719 | 0.574 | 0.755 | 0.770 | 0.843 | YES |

| QD Isometric Strength ND | 0.707 | ||||||

| THD D | 0.792 | ||||||

| THD ND | 0.807 | ||||||

| HS Strength | HS Isometric (brake test) Strength D | 0.922 | 0.802 | 0.919 | 0.932 | 0.942 | YES |

| HS Isometric (brake test) Strength ND | 0.893 | ||||||

| HS Isometric (make test) Strength D | 0.874 | ||||||

| HS Isometric (make test) Strength ND | 0.894 | ||||||

| HS and Core Endurance | Biering–Sorensen Test | 0.571 | 0.572 | 0.847 | 0.867 | 0.888 | YES |

| Prone Bridge | 0.812 | ||||||

| SLHB D | 0.770 | ||||||

| SLHB ND | 0.734 | ||||||

| Side Bridge D | 0.807 | ||||||

| Side Bridge ND | 0.814 | ||||||

| Previous Injuries | Number of Previous Injuries | 0.918 | 0.849 | 0.823 | 0.824 | 0.919 | YES |

| Time Loss | 0.925 | ||||||

| Number of New Non-Contact LL Injuries | Number of injuries | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | YES |

| Factors Interaction | Path Coefficients | T Values | p Values | 95% Confidence Intervals (with Bias Correction) | f-Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABQ → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | −0.232 | 2.923 | 0.003 * | −0.368, −0.051 | 0.062 |

| Ballistic Function → HS and Core Endurance | 0.156 | 1.295 | 0.195 | −0.102, 0.374 | 0.022 |

| HS Strength → Ballistic Function | 0.455 | 6.499 | 0.000 ** | 0.290, 0.577 | 0.260 |

| HS Strength → HS and Core Endurance | 0.248 | 2.428 | 0.015 * | 0.015, 0.424 | 0.056 |

| HS Strength → LL Strength Asymmetries | −0.218 | 1.862 | 0.063 | −0.434, 0.025 | 0.050 |

| HS Strength → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.243 | 2.199 | 0.028 * | 0.012, 0.447 | 0.063 |

| HS and Core Endurance → LL Strength Asymmetries | −0.243 | 2.504 | 0.012 * | −0.408, −0.015 | 0.063 |

| HS and Core Endurance → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.200 | 1.701 | 0.089 | −0.042, 0.417 | 0.041 |

| LL Strength Asymmetries → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.293 | 2.920 | 0.004 * | 0.077, 0.474 | 0.093 |

| Previous Injuries → ABQ | 0.262 | 2.896 | 0.004 * | 0.044, 0.412 | 0.073 |

| Previous Injuries → HS Strength | 0.145 | 1.599 | 0.110 | −0.044, 0.310 | 0.021 |

| Previous Injuries → HS and Core Endurance | −0.207 | 2.182 | 0.029 * | −0.381, −0.008 | 0.049 |

| Previous Injuries → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.233 | 2.442 | 0.015 * | 0.038, 0.418 | 0.059 |

| Factors Interaction | Path Coefficients | T Values | p Values | 95% Confidence Intervals (with Bias Correction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABQ → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | −0.232 | 2.923 | 0.003 * | −0.368, −0.051 |

| Ballistic Function → HS and Core Endurance | 0.156 | 1.295 | 0.195 | −0.102, 0.374 |

| Ballistic Function → LL Strength Asymmetries | −0.038 | 1.032 | 0.302 | −0.126, 0.015 |

| Ballistic Function → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.020 | 0.658 | 0.511 | −0.014, 0.114 |

| HS Strength → Ballistic Function | 0.455 | 6.499 | 0.000 ** | 0.290, 0.577 |

| HS Strength → HS and Core Endurance | 0.319 | 4.069 | 0.000 ** | 0.138, 0.452 |

| HS Strength → LL Strength Asymmetries | −0.295 | 2.645 | 0.008 * | −0.489, −0.049 |

| HS Strength → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.221 | 2.160 | 0.031 * | 0.001, 0.404 |

| HS and Core Endurance → LL Strength Asymmetries | −0.243 | 2.504 | 0.012 * | −0.408, −0.015 |

| HS and Core Endurance → Number of New Non-contact LE Injuries | 0.129 | 1.086 | 0.278 | −0.112, 0.349 |

| LL Strength Asymmetries → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.293 | 2.920 | 0.004 * | 0.077, 0.474 |

| Previous Injuries → ABQ | 0.262 | 2.896 | 0.004 * | 0.044, 0.412 |

| Previous Injuries → Ballistic Function | 0.066 | 1.504 | 0.133 | −0.021, 0.151 |

| Previous Injuries → HS Strength | 0.145 | 1.599 | 0.110 | −0.044, 0.310 |

| Previous Injuries → HS and Core Endurance | −0.161 | 1.527 | 0.127 | −0.355, 0.056 |

| Previous Injuries → LL Strength Asymmetries | 0.007 | 0.154 | 0.877 | −0.089, 0.102 |

| Previous Injuries → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.178 | 2.284 | 0.022 * | 0.018, 0.325 |

| Factor Interaction | Indirect Effect | T Values | p Values | 95% Confidence Intervals (with Bias Correction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballistic Function → LL Strength Asymmetries | −0.038 | 1.032 | 0.302 | −0.126, 0.015 |

| Ballistic Function → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | 0.020 | 0.658 | 0.511 | −0.014, 0.114 |

| HS Strength → HS and Core Endurance | 0.071 | 1.216 | 0.224 | −0.046, 0.185 |

| HS Strength → LL Strength Asymmetries | −0.077 | 2.036 | 0.042 * | −0.157, −0.008 |

| HS Strength → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | −0.023 | 0.407 | 0.684 | −0.139, 0.079 |

| HS and Core Endurance → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | −0.071 | 1.831 | 0.067 | −0.163, −0.008 |

| Previous Injuries → Ballistic Function | 0.066 | 1.504 | 0.133 | −0.021, 0.151 |

| Previous Injuries → HS and Core Endurance | 0.046 | 1.455 | 0.146 | −0.012, 0.114 |

| Previous Injuries → LL Strength Asymmetries | 0.007 | 0.154 | 0.877 | −0.089, 0.102 |

| Previous Injuries → Number of New Non-contact LL Injuries | −0.055 | 1.052 | 0.293 | −0.161, 0.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liveris, N.I.; Tsarbou, C.; Papageorgiou, G.; Tsepis, E.; Xergia, S.A. Interdependent Effect of Intrinsic Risk Factors on Non-Contact Lower Limb Injuries in Male Football Players: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Medicina 2026, 62, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010052

Liveris NI, Tsarbou C, Papageorgiou G, Tsepis E, Xergia SA. Interdependent Effect of Intrinsic Risk Factors on Non-Contact Lower Limb Injuries in Male Football Players: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiveris, Nikolaos I., Charis Tsarbou, George Papageorgiou, Elias Tsepis, and Sofia A. Xergia. 2026. "Interdependent Effect of Intrinsic Risk Factors on Non-Contact Lower Limb Injuries in Male Football Players: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach" Medicina 62, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010052

APA StyleLiveris, N. I., Tsarbou, C., Papageorgiou, G., Tsepis, E., & Xergia, S. A. (2026). Interdependent Effect of Intrinsic Risk Factors on Non-Contact Lower Limb Injuries in Male Football Players: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Medicina, 62(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010052