Oral Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Recognition, Management, and Interdisciplinary Care

Abstract

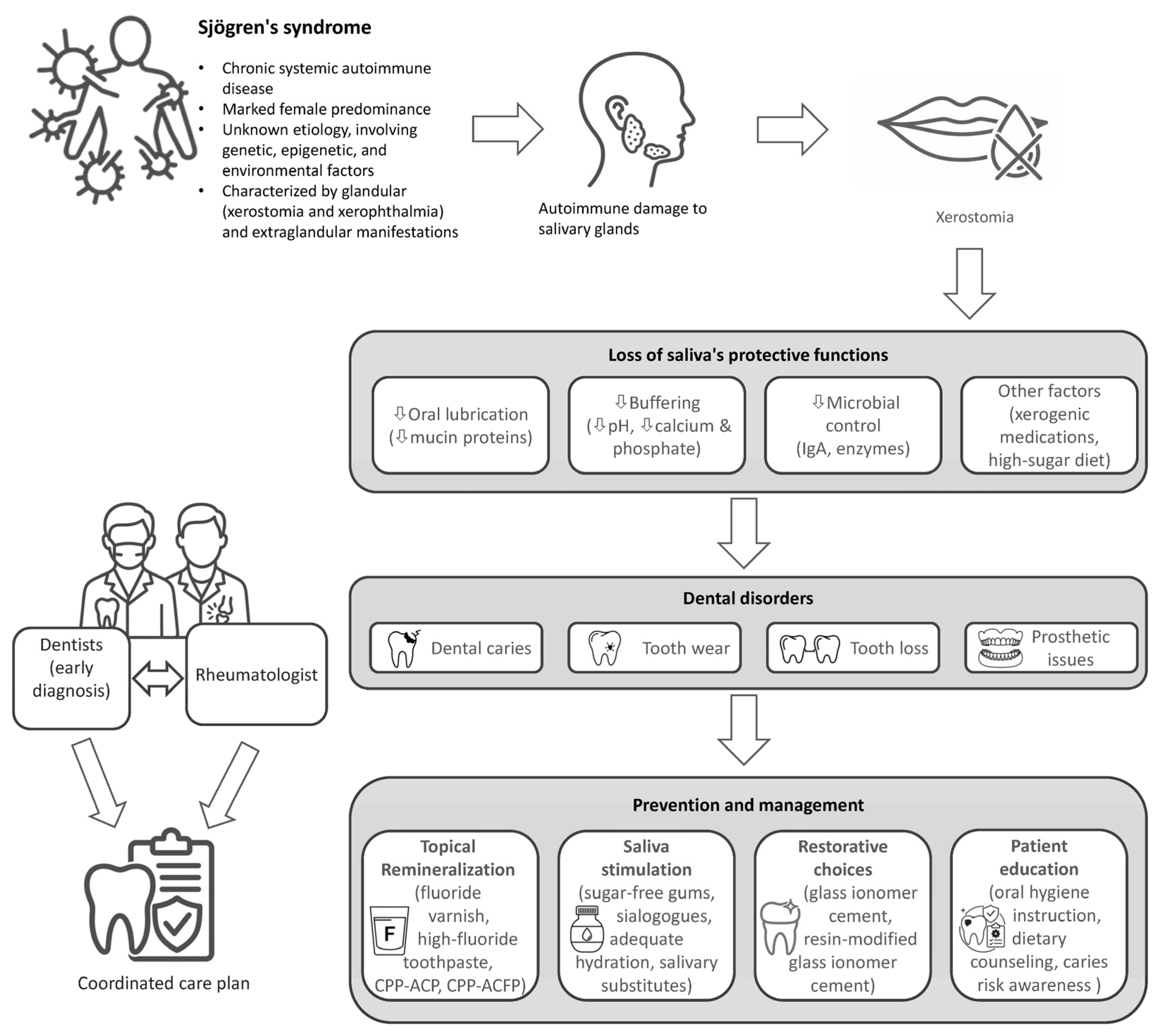

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Dental Disorders in Sjögren’s Syndrome

3.1. Epidemiology of Dental Disorders in Sjögren’s Syndrome

3.2. Immunopathogenesis of Salivary Dysfunction

4. Oral Manifestations in Sjögren’s Syndrome

4.1. Oral Clues for the Diagnosis of Sjögren’s Syndrome

4.2. Histopathologic Considerations: Differentiating Sjögren’s Syndrome from Granulomatous Diseases

4.3. Assessing the Impact of Oral Morbidity on Patient-Reported Outcomes and Systemic Health

4.4. Oral Health as a Factor in Systemic Disease Management

5. Management of Oral Disease in Sjögren’s Syndrome: The Rheumatologist’s Role

5.1. First-Line Patient Counseling and Preventive Education

5.2. Remineralization and Caries Control

5.3. Pharmacologic Management of Salivary Hypofunction

5.4. Facilitating Effective Interdisciplinary Care: The Dental Referral

6. Critical Appraisal of Evidence and Limitations

6.1. Synthesis of Evidence

6.2. Study Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| AECG | American–European Consensus Group |

| aIRR | Adjusted incidence rate ratio |

| anti-SSA/Ro | Anti-Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen A autoantibodies |

| anti-SSB/La | Anti-Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen B autoantibodies |

| BMS | Burning mouth syndrome |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CPP-ACP | Casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate |

| EULAR | European League Against Rheumatism |

| HAP | Hydroxyapatite |

| MSGB | Minor salivary gland biopsy |

| QID | Four times daily |

| RMGICs | Resin-modified glass ionomer cement |

| SS | Sjögren’s syndrome |

| TID | Three times daily |

| UWS | Unstimulated whole saliva |

References

- Maleki-Fischbach, M.; Kastsianok, L.; Koslow, M.; Chan, E.D. Manifestations and management of Sjögren’s disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariette, X.; Criswell, L.A. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, S.S.; Bartels, C.M.; Saldanha, I.J.; Bunya, V.Y.; Akpek, E.K.; Makara, M.A.; Baer, A.N. National Sjögren’s Foundation survey: Burden of oral and systemic involvement on quality of life. J. Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartee, D.L.; Maker, S.; Dalonges, D.; Manski, M.C. Sjögren’s syndrome: Oral manifestations and treatment, a dental perspective. J. Dent. Hyg. 2015, 89, 365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Margaix-Muñoz, M.; Bagán, J.V.; Poveda, R.; Jiménez, Y.; Sarrión, G. Sjögren’s syndrome of the oral cavity: Review and update. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2009, 14, e325–e330. [Google Scholar]

- Šijan Gobeljić, M.; Milić, V.; Pejnović, N.; Damjanov, N. Chemosensory dysfunction, oral disorders and oral health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, C.J.; Hsu, C.W.; Lu, M.C.; Koo, M. Increased risk of developing dental diseases in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A secondary cohort analysis of population-based claims data. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, E.; D’Albenzio, A.; Rapone, B.; Balice, G.; Murmura, G. Cross-population analysis of Sjögren’s syndrome polygenic risk scores and disease prevalence: A pilot study. Genes 2025, 16, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Yang, M.; Ma, N.; Huang, F.; Zhong, R. Epidemiology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 1983–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, G.; Crowson, C.S.; Matteson, E.L.; Cornec, D. Prevalence of primary Sjögren’s syndrome in a US population-based cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 69, 1612–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarse, F.; Jager, D.H.; Forouzanfar, T.; Wolff, J.; Brand, H.S. Tooth loss in Sjögren’s syndrome patients compared to age- and gender-matched controls. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2018, 23, e545–e551. [Google Scholar]

- Orliaguet, M.; Vallaeys, K.; Leger, S.; Decup, F.; Grosgogeat, B.; Gosset, M. Dental needs in patients with Sjögren’s disease compared to the general population: A cross-sectional study. J. Dent. 2025, 159, 105816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckelkamm, S.L.; Alayash, Z.; Holtfreter, B.; Nolde, M.; Baumeister, S.E. Sjögren’s disease and oral health: A genetic instrumental variable analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Ma, J.; Cui, J.; Gu, Y.; Shan, Y. Subpopulation dynamics of T and B lymphocytes in Sjögren’s syndrome: Implications for disease activity and treatment. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1468469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, H.; Ovitt, C.E. Novel impacts of saliva with regard to oral health. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Nie, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Y. Effects of Sjögren’s syndrome and high sugar diet on oral microbiome in patients with rampant caries: A clinical study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, M.; Epstein, J.; Villines, D. Managing the care of patients with Sjögren syndrome and dry mouth: Comorbidities, medication use and dental care considerations. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2014, 145, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, N.; Vivino, F.; Baker, J.; Dunham, J.; Pinto, A. Risk factors for caries development in primary Sjögren syndrome. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 128, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lacombe, V.; Lacout, C.; Lozac’h, P.; Ghali, A.; Gury, A.; Lavigne, C.; Urbanski, G. Unstimulated whole saliva flow for diagnosis of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Time to revisit the threshold? Arthritis Res. Ther. 2022, 22, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.B.; Vissink, A. Salivary gland dysfunction and xerostomia in Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 26, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ergun, S.; Cekici, A.; Topcuoglu, N.; Migliari, D.A.; Külekçi, G.; Tanyeri, H.; Isik, G. Oral status and Candida colonization in patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2010, 15, e310–e315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.C.; Tseng, C.F.; Wang, Y.H.; Yu, H.C.; Chang, Y.C. Patients with chronic periodontitis present increased risk for primary Sjögren syndrome: A nationwide population-based cohort study. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanobi, H.; Sabharwal, A.; Krishnakumar, B.; Kramer, J.M. Is it Sjögren’s syndrome or burning mouth syndrome? Distinct pathoses with similar oral symptoms. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2017, 123, 482–495. [Google Scholar]

- AlMannai, A.I.; Alaradi, K.; Almahari, S.A.I. Accuracy of labial salivary gland biopsy in suspected cases of Sjogren’s syndrome. Cureus 2024, 16, e74746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossides, M.; Darlington, P.; Kullberg, S.; Arkema, E.V. Sarcoidosis: Epidemiology and clinical insights. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 293, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Dioguardi, M.; Giannatempo, G.; Laino, L.; Testa, N.F.; Cocchi, R.; De Lillo, A.; Lo Muzio, L. Orofacial granulomatosis: Clinical signs of different pathologies. Med. Princ. Pract. 2015, 24, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Amarnath, S.; Deeb, L.; Philipose, J.; Zheng, X.; Gumaste, V. A comprehensive review of infectious granulomatous diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 8167149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawi, F.; Shields, B.E.; Omolehinwa, T.; Rosenbach, M. Oral granulomatous disease. Dermatol. Clin. 2020, 38, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusthen, S.; Young, A.; Herlofson, B.B.; Aqrawi, L.A.; Rykke, M.; Hove, L.H.; Palm, Ø.; Jensen, J.L.; Singh, P.B. Oral disorders, saliva secretion, and oral health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2017, 125, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, F.; Patano, A.; Guglielmo, M.; Palumbo, I.; Campanelli, M.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Malcangi, G.; Palermo, A.; Tartaglia, F.C.; et al. Dental erosion and the role of saliva: A systematic review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 10651–10660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen, A.E.; Allen, P.F.; Witter, D.J.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Creugers, N.H. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, K.; Callhoff, J.; Westhoff, G.; Dietrich, T.; Dörner, T.; Zink, A. The prevalence of dental implants and related factors in patients with Sjögren syndrome: Results from a cohort study. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.S.; Drumond, V.Z.; de Arruda, J.A.A.; de Sousa, R.A.; Araújo, T.L.; de Sousa, S.F.; Silva, T.A.; Mesquita, R.A.; Abreu, L.G. Burden of tooth loss in individuals with Sjögren disease: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. J. Dent. 2025, 160, 105845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshparvar, H.; Esfahanizadeh, N.; Vafadoost, R. Dental implants in Sjögren syndrome. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2020, 30, 8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Pang, X.; Guan, J.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, B. The association of periodontal diseases and Sjögren’s syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2023, 9, 904638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, S.; Kirschstein, L.; Knopf, A.; Mansour, N.; Jeleff-Wölfler, O.; Buchberger, A.M.S.; Hofauer, B. Systematic evaluation of laryngeal impairment in Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 278, 2421–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, G.G.F.; Wang, M.; Siddiqui, Z.A.; Gonzalez, T.; Capin, O.R.; Willis, L.; Boyd, L.; Eckert, G.J.; Zero, D.T.; Thyvalikakath, T.P. Longevity of dental restorations in Sjögren’s disease patients using electronic dental and health record data. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyldahl, E.; Gotfredsen, K.; Pedersen, A.M.; Storgård Jensen, S. Survival and success of dental implants in patients with autoimmune diseases: A systematic review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 2024, 15, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.J.; Benjamin, S.; Bombardieri, M.; Bowman, S.; Carty, S.; Ciurtin, C.; Crampton, B.; Dawson, A.; Fisher, B.A.; Giles, I.; et al. British Society for Rheumatology guideline on management of adult and juvenile onset Sjögren disease. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 409–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Bombardieri, S.; Bootsma, H.; De Vita, S.; Dörner, T.; Fisher, B.A.; Gottenberg, J.E.; Hernandez-Molina, G.; Kocher, A.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of Sjögren’s syndrome with topical and systemic therapies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavandgar, Z.; Warner, B.M.; Baer, A.N. Evaluation and management of dry mouth and its complications in rheumatology practice. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2024, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathi, D.; Sailo, J.L.; Ausare, S.S.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Buvariya, S.; Dolker, T.; Maini, A.P. Management strategies for xerostomia in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: A comprehensive review. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2025, 17, S74–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyant, R.J.; Tracy, S.L.; Anselmo, T.T.; Beltrán-Aguilar, E.D.; Donly, K.J.; Frese, W.A.; Hujoel, P.P.; Iafolla, T.; Kohn, W.; Kumar, J.; et al. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Topical Fluoride Caries Preventive Agents. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: Executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2013, 144, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, W.; Leung, K.C.; Lo, E.C.; Mok, M.Y.; Leung, M.H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of fluoride varnish in preventing dental caries of Sjögren’s syndrome patients. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limeback, H.; Enax, J.; Meyer, F. Biomimetic hydroxyapatite and caries prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2021, 55, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Paszynska, E.; Pawinska, M.; Enax, J.; Meyer, F.; Schulze Zur Wiesche, E.; May, T.W.; Amaechi, B.T.; Limeback, H.; Hernik, A.; Otulakowska-Skrzynska, J.; et al. Caries-preventing effect of a hydroxyapatite-toothpaste in adults: A 18-month double-blinded randomized clinical trial. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1199728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmath Meeral, P.; Doraikannan, S.; Indiran, M.A. Efficiency of casein phosphopeptide amorphous calcium phosphate versus topical fluorides on remineralizing early enamel carious lesions—A systematic review and meta analysis. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Golzio Navarro Cavalcante, B.; Schulze Wenning, A.; Szabó, B.; László Márk, C.; Hegyi, P.; Borbély, J.; Németh, O.; Bartha, K.; Gerber, G.; Varga, G. Combined casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate and fluoride is not superior to fluoride alone in early carious lesions: A meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2024, 58, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zero, D.T.; Brennan, M.T.; Daniels, T.E.; Papas, A.; Stewart, C.; Pinto, A.; Al-Hashimi, I.; Navazesh, M.; Rhodus, N.; Sciubba, J.; et al. Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee. Clinical practice guidelines for oral management of Sjögren disease: Dental caries prevention. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2016, 147, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Hajikolaei, F.A.; Hoseinpour, F.; Hashemi, S.A.; Fatehi, A.; Pakmehr, S.A.; Deravi, N.; Naziri, M.; Belbasi, M.; Khoshravesh, S.; et al. Efficacy of cevimeline on xerostomia in Sjögren’s syndrome patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2024, 102, 100770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Villa, A.; Connell, C.L.; Abati, S. Diagnosis and management of xerostomia and hyposalivation. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2014, 11, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, M.; Del Barrio-Díaz, P.; Vera-Kellet, C. Pilocarpine and artificial saliva for the treatment of xerostomia and xerophthalmia in Sjögren syndrome: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, S.; Worthington, H.V.; Bryan, G.; Birchenough, S.; McMillan, R. Interventions for the management of dry mouth: Topical therapies. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 12, CD008934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, S.; Bryan, G.; McMillan, R.; Worthington, H.V. Interventions for the management of dry mouth: Non-pharmacological interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, CD009603. [Google Scholar]

- Marinho, V.C.; Worthington, H.V.; Walsh, T.; Clarkson, J.E. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 7, CD002279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, D.A.; Frostad-Thomas, A.; Gold, J.; Wong, A. Secondary Sjögren syndrome: A case report using silver diamine fluoride and glass ionomer cement. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2018, 149, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, B.B.F.; Cabral-Oliveira, G.G.; Monnerat, A.F.; Brito, F. Use of high viscosity glass-ionomer cement as a restorative material in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: A case report. Br. J. Dent. 2021, 78, e1968. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, N.S.; Jorge, G.R.; Vasconcelos, J.; Probst, L.F.; De-Carli, A.D.; Freire, A. Clinical efficacy of bioactive restorative materials in controlling secondary caries: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, R.J.; Stassen, I.G.; van’t Veldt, Y.; Torbeyns, D.; Hommez, G.M. Two-year clinical performance of glass ionomer and resin composite restorations in xerostomic head- and neck-irradiated cancer patients. Clin. Oral Investig. 2011, 15, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tonprasong, W.; Inokoshi, M.; Shimizubata, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Hatano, K.; Minakuchi, S. Impact of direct restorative dental materials on surface root caries treatment: Evidence based and current materials development: A systematic review. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2022, 58, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panetta, A.; Lopes, P.; Novaes, T.F.; Rio, R.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Mello-Moura, A.C.V. Evaluating glass ionomer cement longevity in the primary and permanent teeth: An umbrella review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leinonen, J.; Vähänikkilä, H.; Raninen, E.; Järvelin, L.; Näpänkangas, R.; Anttonen, V. The survival time of restorations is shortened in patients with dry mouth. J. Dent. 2021, 113, 103794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Jensen, S.S.; Gotfredsen, K.; Hyldahl, E.; Pedersen, A.M.L. Prognosis of single implant-supported prosthesis in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A five-year prospective clinical study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2025, 36, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.I. Advances in soft denture liners: An update. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2015, 16, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Clinical Observations & Considerations | First-Line Action | Criteria for Dental Referral |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Intervention | Recommended Frequency | Clinical Role & Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|

| Caries Prevention | ||

| High-fluoride toothpaste (5000 ppm) | Twice daily | Anchor Measure. Supported by professional guidelines for high-risk adults; considered the standard of care. |

| Fluoride varnish (5% NaF) | Every 3 months (Professional) | Adjunct Option. Evidence in SS-specific trials is mixed; recommended based on individual caries activity rather than universal application. |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAP) dentifrice | Twice daily | Alternative/Adjunct. Recent trials suggest non-inferiority to fluoride; suitable for patients preferring fluoride-free options. |

| CPP-ACP formulations | Daily/As needed | Adjunct. Evidence is inconsistent regarding added benefit over fluoride alone; may aid remineralization of early lesions. |

| Salivary Stimulation & Hydration | ||

| Mechanical stimulation (sugar-free gum/lozenges) | As needed | First-Line Symptomatic. Xylitol-containing products preferred to reduce caries risk; effective for transient relief. |

| Systemic sialogogues (Pilocarpine, Cevimeline) | Prescribed regimen (e.g., TID/QID) | Second-Line Therapeutic. Effective for increasing flow; requires screening for contraindications. |

| Restorative Approach | ||

| Glass Ionomer/RMGIC | As required for lesions | Preferred Material. Releases fluoride and chemically bonds to tooth structure; lower failure rate than composite resin in dry mouths. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, S.-C.; Lu, M.-C.; Koo, M. Oral Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Recognition, Management, and Interdisciplinary Care. Medicina 2026, 62, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010005

Liu S-C, Lu M-C, Koo M. Oral Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Recognition, Management, and Interdisciplinary Care. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shu-Cheng, Ming-Chi Lu, and Malcolm Koo. 2026. "Oral Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Recognition, Management, and Interdisciplinary Care" Medicina 62, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010005

APA StyleLiu, S.-C., Lu, M.-C., & Koo, M. (2026). Oral Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Recognition, Management, and Interdisciplinary Care. Medicina, 62(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010005