TAVI Performance at a Single Center over Several Years: Procedural and Clinical Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Pre-Procedural Evaluation

2.3. TAVI Procedure

2.4. High Implantation Technique

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

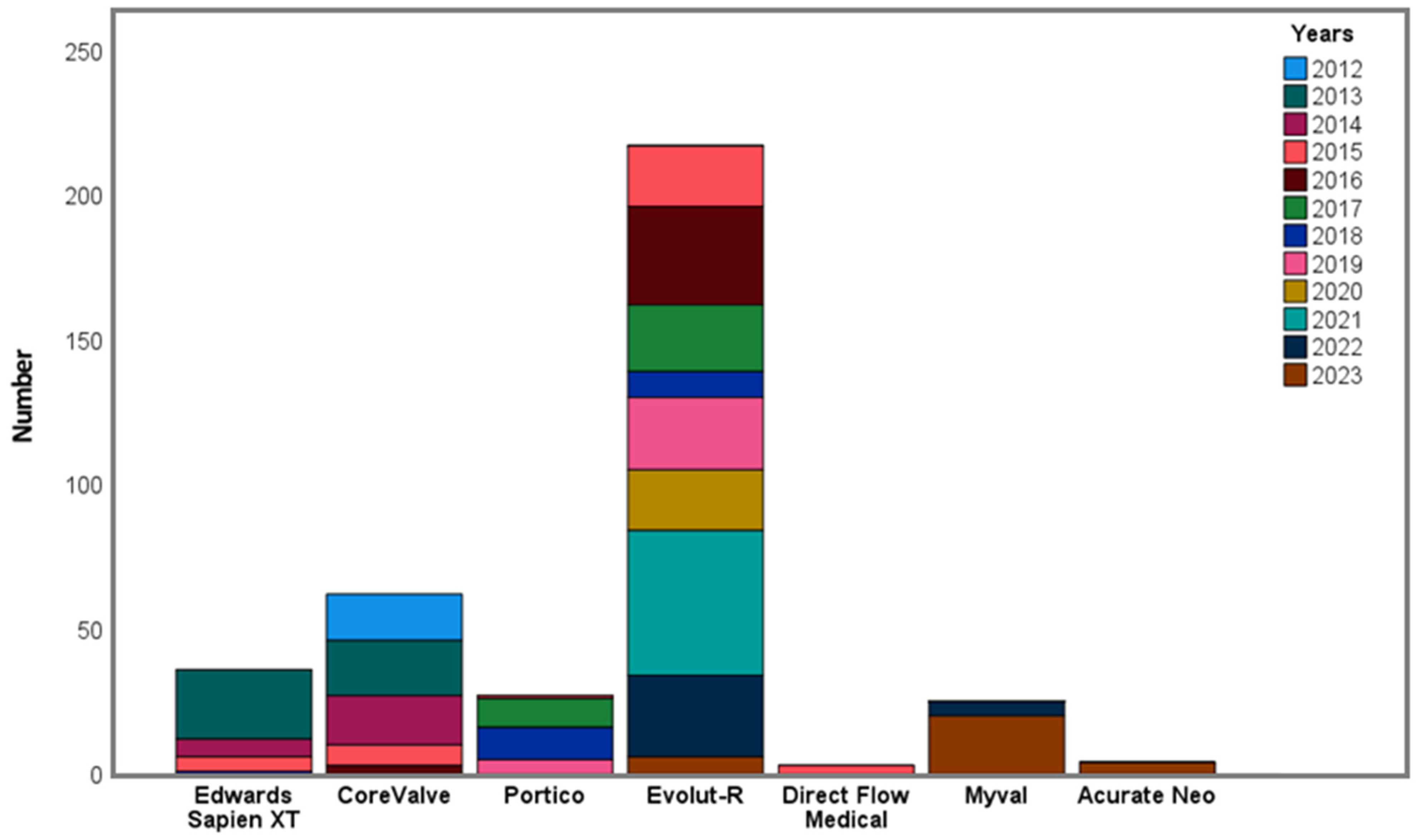

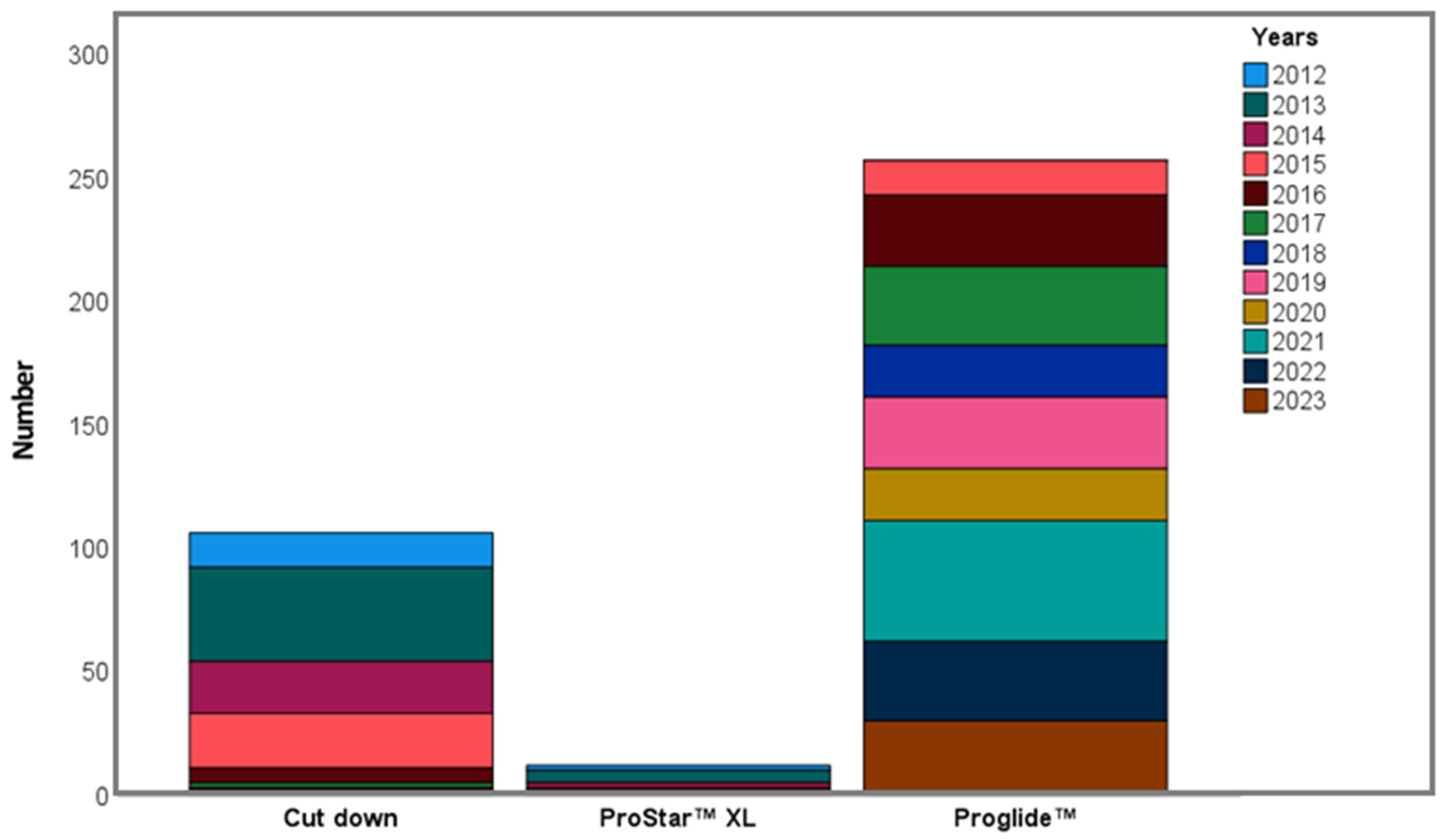

3.2. Procedural Characteristics

3.3. Procedural Outcomes

3.4. Mortality

3.5. Other Complications

3.6. Antiplatelet and/or Anticoagulant Regimen

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TAVI | Transcatheter aortic valve implantation |

| AS | Aortic stenosis |

| VARC-3 | Valve Academic Research Consortium-3 |

| PPM | Permanent pacemaker implantation |

| ESV | Edwards SAPIEN valve |

| MCV | Medtronic CoreValve |

| DFM | Direct Flow Medical |

| STS PROM | Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predictive Risk for Mortality |

| EuroSCORE I, II | Logistic European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Scores |

| PVL | Paravalvular leakage |

| TTE | Transthoracic echocardiography |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| AVA | Aortic valve area |

| TEE | Transesophageal echocardiography |

| MSCT | Multi-slice computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| CAG | Coronary angiography |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| VSD | Ventricular septal defect |

References

- Praz, F.; Borger, M.A.; Lanz, J.; Marin-Cuartas, M.; Abreu, A.; Adamo, M.; Ajmone, M.N.; Barili, F.; Bonaros, N.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4635–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribier, A.; Eltchaninoff, H.; Bash, A.; Borenstein, N.; Tron, C.; Bauer, F.; Derumeaux, G.; Anselme, F.; Laborde, F.; Leon, M.B. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: First human case description. Circulation 2002, 106, 3006–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, G.; Paker, T.; Akçevin, A.; Sezer, A.; Eryilmaz, A.; Ozyiğit, T.; Sezer, A.; Akpek, S.; Türkoğlu, H.; Cribier, A. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: The first applications and early results in Turkey. Turk. Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2010, 38, 258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, M.B.; Smith, C.R.; Mack, M.; Miller, D.C.; Moses, J.W.; Svensson, L.G.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Webb, J.G.; Fontana, G.P.; Makkar, R.R.; et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, M.B.; Smith, C.R.; Mack, M.J.; Makkar, R.R.; Svensson, L.G.; Kodali, S.K.; Thourani, V.H.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Miller, D.C.; Herrmann, H.C.; et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensey, M.; Murdoch, D.J.; Sathananthan, J.; Alenezi, A.; Sathananthan, G.; Moss, R.; Blanke, P.; Leipsic, J.; Wood, D.A.; Cheung, A.; et al. First-in-human experience of a new-generation transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve for the treatment of severe aortic regurgitation: The J-Valve transfemoral system. EuroIntervention 2019, 14, e1553–e1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahhab, Z.; El Faquir, N.; Tchetche, D.; Delgado, V.; Kodali, S.; Mara, V.E.; Bax, J.; Leon, M.B.; Van Mieghem, N.M. Expanding the indications for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantini, G.; Dvir, D.; Tang, G.H.L. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in degenerated surgical aortic valves. EuroIntervention 2021, 17, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltchaninoff, H.; Prat, A.; Gilard, M.; Leguerrier, A.; Blanchard, D.; Fournial, G.; Iung, B.; Donzeau-Gouge, P.; Tribouilloy, C.; Debrux, J.L.; et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: Early results of the FRANCE (FRench Aortic National CoreValve and Edwards) registry. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moat, N.E.; Ludman, P.; de Belder, M.A.; Bridgewater, B.; Cunningham, A.D.; Young, C.P.; Thomas, M.; Kovac, J.; Spyt, T.; MacCarthy, P.A.; et al. Long-term outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: The U.K. TAVI (United Kingdom Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2130–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurvitch, R.; Tay, E.L.; Wijesinghe, N.; Ye, J.; Nietlispach, F.; Wood, D.A.; Lichtenstein, S.; Cheung, A.; Webb, J.G. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: Lessons from the learning curve of the first 270 high-risk patients. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 78, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Généreux, P.; Piazza, N.; Alu, M.C.; Nazif, T.; Hahn, R.T.; Pibarot, P.; Bax, J.J.; Leipsic, J.A.; Blanke, P.; Blackstone, E.H.; et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: Updated Endpoint Definitions for Aortic Valve Clinical Research. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 2717–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahanian, A.; Alfieri, O.; Andreotti, F.; Antunes, M.J.; Barón-Esquivias, G.; Baumgartner, H.; Borger, M.A.; Carrel, T.P.; De Bonis, M.; Evangelista, A.; et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2451–2496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, H.; Falk, V.; Bax, J.J.; De Bonis, M.; Hamm, C.; Holm, P.J.; Iung, B.; Lancellotti, P.; Lansac, E.; Muñoz, D.R.; et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2739–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; De Bonis, M.; De Paulis, R.; et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 75, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, R.A.; Otto, C.M.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P., 3rd; Guyton, R.A.; O’Gara, P.T.; Ruiz, C.E.; Skubas, N.J.; Sorajja, P.; et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, e57–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorano, J.L.; Badano, L.P.; Bruce, C.; Chan, K.L.; Gonçalves, A.; Hahn, R.T.; Keane, M.G.; La Canna, G.; Monaghan, M.J.; Nihoyannopoulos, P.; et al. EAE/ASE recommendations for the use of echocardiography in new transcatheter interventions for valvular heart disease. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2011, 24, 937–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, H.; Hung, J.; Bermejo, J.; Chambers, J.B.; Edvardsen, T.; Goldstein, S.; Lancellotti, P.; LeFevre, M.; Miller, F., Jr.; Otto, C.M. Recommendations on the Echocardiographic Assessment of Aortic Valve Stenosis: A Focused Update from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, S.; Delgado, V.; Hausleiter, J.; Schoenhagen, P.; Min, J.K.; Leipsic, J.A. SCCT expert consensus document on computed tomography imaging before transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)/transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2012, 6, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, T.; Yamanaka, F.; Shishido, K.; Moriyama, N.; Komatsu, I.; Yokoyama, H.; Miyashita, H.; Sato, D.; Sugiyama, Y.; Hayashi, T.; et al. Impact of High Implantation of Transcatheter Aortic Valve on Subsequent Conduction Disturbances and Coronary Access. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 16, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, V.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Bleiziffer, S.; Veulemans, V.; Sedaghat, A.; Adam, M.; Nickenig, G.; Kelm, M.; Thiele, H.; Baldus, S.; et al. Temporal trends of TAVI treatment characteristics in high volume centers in Germany 2013-2020. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2022, 111, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier, R.; Le Breton, H.; Eltchaninoff, H.; Cayla, G.; Commeau, P.; Collet, J.P.; Cuisset, T.; Dumonteil, N.; Verhoye, J.P.; Beurtheret, S.; et al. Evolution of TAVI patients and techniques over the past decade: The French TAVI registries. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 115, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuzcu, E.M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Vemulapalli, S.; Carroll, J.D.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Mack, M.J.; Thourani, V.H.; Grover, F.L.; Brennan, J.M.; Suri, R.M.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement of Failed Surgically Implanted Bioprostheses: The STS/ACC Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizu, K.; Shirai, S.; Isotani, A.; Hayashi, M.; Kawaguchi, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Ando, K.; Yashima, F.; Tada, N.; Yamawaki, M.; et al. Long-Term Prognostic Value of the Society of Thoracic Surgery Risk Score in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (From the OCEAN-TAVI Registry). Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 149, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmann, K.; Sirotina, M.; De Rosa, S.; Ehrlich, J.R.; Fox, H.; Weber, J.; Moritz, A.; Zeiher, A.M.; Hofmann, I.; Schächinger, V.; et al. The STS score is the strongest predictor of long-term survival following transcatheter aortic valve implantation, whereas access route (transapical versus transfemoral) has no predictive value beyond the periprocedural phase. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 17, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourantas, C.V.; Modolo, R.; Baumbach, A.; Søndergaard, L.; Prendergast, B.D.; Ozkor, M.; Kennon, S.; Mathur, A.; Mullen, M.J.; Serruys, P.W. The evolution of device technology in transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention 2019, 14, e1826–e1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarito, M.; Spirito, A.; Nicolas, J.; Selberg, A.; Stefanini, G.; Colombo, A.; Reimers, B.; Kini, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Dangas, G.D.; et al. Evolving Devices and Material in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: What to Use and for Whom. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotti, A.; Baggio, S.; Pagnesi, M.; Barbanti, M.; Adamo, M.; Eitan, A.; Estévez-Loureiro, R.; Veulemans, V.; Toggweiler, S.; Mylotte, D.; et al. Temporal Trends and Contemporary Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement With Evolut PRO/PRO+ Self-Expanding Valves: Insights From the NEOPRO/NEOPRO-2 Registries. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 16, e012538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessen, B.E.; Tang, G.H.L.; Kini, A.S.; Sharma, S.K. Considerations for Optimal Device Selection in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolos, A.; Ktenopoulos, N.; Drakopoulou, M.; Ielasi, A.; Panoulas, V.; Baumbach, A.; Tsioufis, K.; Serruys, P.; Toutouzas, K. Effectiveness and Safety of Myval Versus Other Transcatheter Valves in Patients Undergoing TAVI: A Meta-Analysis. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2025, 106, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, M.W.; Xiang, K.; Matsouaka, R.; Li, Z.; Vemulapalli, S.; Vora, A.N.; Fanaroff, A.; Harrison, J.K.; Thourani, V.H.; Holmes, D.; et al. Incidence, Temporal Trends, and Associated Outcomes of Vascular and Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Insights From the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapies Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, e008227. [Google Scholar]

- Thieme, M.; Moebius-Winkler, S.; Franz, M.; Baez, L.; Schulze, C.P.; Butter, C.; Edlinger, C.; Kretzschmar, D. Interventional Treatment of Access Site Complications During Transfemoral TAVI: A Single Center Experience. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 725079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postolache, A.; Sperlongano, S.; Lancellotti, P. TAVI after More Than 20 Years. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warraich, N.; Brown, J.A.; Ashwat, E.; Kliner, D.; Serna-Gallegos, D.; Toma, C.; West, D.; Makani, A.; Wang, Y.; Sultan, I. Paravalvular Leak After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Results From 3600 Patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2025, 119, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synetos, A.; Ktenopoulos, N.; Katsaros, O.; Vlasopoulou, K.; Drakopoulou, M.; Koliastasis, L.; Kachrimanidis, I.; Apostolos, A.; Tsalamandris, S.; Latsios, G.; et al. Paravalvular Leak in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: A Review of Current Challenges and Future Directions. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D.; Tanriverdi, Z.; Dursun, H.; Colluoglu, T. Echocardiographic outcomes of self-expandable CoreValve versus balloon-expandable Edwards SAPIEN XT valves: The comparison of two bioprosthesis implanted in a single centre. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 32, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Rmilah, A.A.; Al-Zu’bi, H.; Haq, I.U.; Yagmour, A.H.; Jaber, S.A.; Alkurashi, A.K.; Qaisi, I.; Kowlgi, G.N.; Cha, Y.M.; Mulpuru, S.; et al. Predicting permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: A contemporary meta-analysis of 981,168 patients. Heart Rhythm O2 2022, 3, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasel, A.M.; Cassese, S.; Ischinger, T.; Leber, A.; Antoni, D.; Riess, G.; Vogel, J.; Kastrati, A.; Eichinger, W.; Hoffmann, E. A prospective, non-randomized comparison of SAPIEN XT and CoreValve implantation in two sequential cohorts of patients with severe aortic stenosis. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 4, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Wahab, M.; Mehilli, J.; Frerker, C.; Neumann, F.J.; Kurz, T.; Tölg, R.; Zachow, D.; Guerra, E.; Massberg, S.; Schäfer, U.; et al. Comparison of balloon-expandable vs self-expandable valves in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: The CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.R.; Leon, M.B.; Mack, M.J.; Miller, D.C.; Moses, J.W.; Svensson, L.G.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Webb, J.G.; Fontana, G.P.; Makkar, R.R.; et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2187–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, M.J.; Leon, M.B.; Thourani, V.H.; Makkar, R.; Kodali, S.K.; Russo, M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Malaisrie, S.C.; Cohen, D.J.; Pibarot, P.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilard, M.; Eltchaninoff, H.; Iung, B.; Donzeau-Gouge, P.; Chevreul, K.; Fajadet, J.; Leprince, P.; Leguerrier, A.; Lievre, M.; Prat, A.; et al. Registry of transcatheter aortic-valve implantation in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoum, I.; Eitan, A.; Sliman, H.; Shiran, A.; Adawi, S.; Asmer, I.; Zissman, K.; Jaffe, R. Cardiac Tamponade Complicating Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Insights From a Single-Center Registry. CJC Open 2025, 7, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelo, A.; Grazina, A.; Teixeira, B.; Mendonça, T.; Rodrigues, I.; Garcia Brás, P.; Vaz, F.V.; Ramos, R.; Fiarresga, A.; Cacela, D.; et al. Outcomes and predictors of periprocedural stroke after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 32, 107054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond-Haley, M.; Almohtadi, A.; Gonnah, A.R.; Raha, O.; Khokhar, A.; Hartley, A.; Khawaja, S.; Hadjiloizou, N.; Ruparelia, N.; Mikhail, G.; et al. Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: A Systematic Review and Multidisciplinary Treatment Recommendations. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.; Merdler, I.; Ben-Dor, I.; Satler, L.F.; Rogers, T.; Waksman, R. Cerebrovascular events after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention 2024, 20, e793–e805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butala, A.D.; Nanayakkara, S.; Navani, R.V.; Palmer, S.; Noaman, S.; Haji, K.; Htun, N.M.; Walton, A.S.; Stub, D. Acute Kidney Injury Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation-A Contemporary Perspective of Incidence, Predictors, and Outcomes. Heart Lung Circ. 2024, 33, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes Filho, A.C.B.; Katz, M.; Campos, C.M.; Carvalho, L.A.; Siqueira, D.A.; Tumelero, R.T.; Portella, A.L.F.; Esteves, V.; Perin, M.A.; Sarmento-Leite, R.; et al. Impact of Acute Kidney Injury on Short- and Long-term Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 72, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, J.K.; Østergaard, L.; Carlson, N.; Bager, L.G.V.; Strange, J.E.; Schou, M.; Køber, L.; Fosbøl, E.L. Impact of Acute Kidney Injury After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Nationwide Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e031019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiritano, F.; Serraino, G.F.; Sorrentino, S.; Napolitano, D.; Costa, D.; Ielapi, N.; Bracale, U.M.; Mastroroberto, P.; Andreucci, M.; Serra, R. Risk of Bleeding in Elderly Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation or Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P., 3rd; Gentile, F.; Jneid, H.; Krieger, E.V.; Mack, M.; McLeod, C.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021, 143, e35–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeniou, V.; Chen, S.; Gilon, D.; Segev, A.; Finkelstein, A.; Planer, D.; Barbash, I.; Halkin, A.; Beeri, R.; Lotan, C.; et al. Ventricular Septal Defect as a Complication of TAVI: Mechanism and Incidence. Struct. Heart 2018, 2, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, H.; Erdal, C.; Ergene, O.; Unal, B.; Tanriverdi, Z.; Kaya, D. Treatment of an unusual complication of transfemoral TAVI with a new technique: Successful occlusion of ventricular septal defect by opening the closure device in the ascending aorta. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2015, 26, e8–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | All Patients Who Underwent TAVI (n = 375) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 78.4 ± 7.3 |

| Gender, male (%) | 161 (42.9) |

| HT (%) | 314 (83.7) |

| DM (%) | 154 (41.1) |

| CAD (%) | 161 (42.9) |

| COPD (%) | 88 (23.5) |

| CABG (%) | 72 (19.2) |

| Valve surgery (%) | 21 (5.6) |

| Peripheral artery disease (%) | 27 (7.2) |

| PPM history (%) | 19 (5.1) |

| Malignancy (%) | 29 (7.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.0 ± 4.5 |

| STS score (%) | 4.2 (2.9–5.9) |

| Euroscore II (%) | 4.2 (2.7–6.2) |

| Pre-op mean gradient, mmHg | 45 (38–55) |

| Pre-op AVA, cm2 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| Pre-op EF (%) | 52.0 ± 13.7 |

| Variables | All Patients Who Underwent TAVI |

|---|---|

| (n = 375) | |

| Pre-TAVI PCI (%) | 56 (14.9) |

| Valve type (%) | |

| ESV | 36 (9.6) |

| CoreValve | 61 (16.3) |

| Evolut R | 218 (58.1) |

| Portico | 27 (7.2) |

| Myval | 25 (6.7) |

| DFM | 3 (0.8) |

| Acurate Neo | 4 (1.1) |

| Aortic valve pre-dilatation (%) | 205 (54.7) |

| Aortic valve post-dilatation (%) | 55 (14.7) |

| Valve-in-TAVI (%) | 5 (1.3) |

| Valve-in-valve (%) | 5 (1.3) |

| Access type | |

| Surgical cutdown | 106 (28.3) |

| Percutaneous | 269 (71.7) |

| Prostar | 12 (4.5) |

| Proglide | 257 (95.5) |

| Duration of ICU stay, days | 3 (3–5) |

| Anesthesia type (%) | |

| Endotracheal intubation | 109 (29.1) |

| Local anesthesia | 266 (70.9) |

| Post-operative ES transfusion requirement (%) | 103 (27.4) |

| Number of ES transfusions | 1 (0–2) |

| Variables | All Patients Who Underwent TAVI (n = 375) |

|---|---|

| Successful valve implantation (%) | 365 (97.8) |

| Device success (%) | 320 (85.3) |

| Technical success (%) | 339 (90.4) |

| Device embolization (%) | 4 (1.1) |

| Second valve implantation (%) | 7 (1.9) |

| Cardiac complication (%) | 12 (3.2) |

| Vascular complication (%) | 42 (11.2) |

| Major vascular complication (%) | 18 (4.8) |

| PPM requirement (%) | 42 (11.2) |

| Moderate or worse PVL (%) | 11 (2.9) |

| Stroke (%) | 6 (1.6) |

| Acute kidney injury (%) | 27 (7.2) |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 15 (4.0) |

| Vascular Complication Type (No. of Cases) | Treatment Modality (No. of Cases) |

|---|---|

| Significant or total occlusion of common femoral artery (15) | Balloon angioplasty (7) |

| Stent implantation (5) | |

| Surgery (3) | |

| Rupture of common femoral artery (9) | Surgery (8) |

| Graft stent implantation (1) | |

| Pseudoaneurysm (7) | Surgery (3) |

| Follow-up (4) | |

| AV fistula (3) | Follow-up (1) |

| Surgery (2) | |

| Femoral hematoma (3) | Follow-up (1) |

| Surgery (2) | |

| Aortic dissection (1) | Follow-up (1) |

| Deep venous thrombosis (2) | ECHOS—slow thrombolytic injection (1) |

| Anticoagulant (1) | |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma (1) | Follow-up (1) |

| Lower-extremity emboli (1) | Surgery (1) |

| Variables | All Patients Who Underwent TAVI (n = 375) |

|---|---|

| Aspirin or clopidogrel alone (%) | 41 (10.9) |

| Aspirin + clopidogrel (%) | 223 (59.5) |

| Warfarin alone (%) | 25 (6.7) |

| Warfarin + aspirin (%) | 2 (0.5) |

| Warfarin + clopidogrel (%) | 13 (3.5) |

| Warfarin + aspirin + clopidogrel (%) | 6 (1.6) |

| NOACs alone (%) | 43 (11.5) |

| NOACs + clopidogrel (%) | 22 (5.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dursun, H.; Senturk, B.; Colluoglu, T.; Oktay, C.; Uysal, H.; Simsek, H.T.; Karaoglan, S.; Tanriverdi, Z.; Kaya, D. TAVI Performance at a Single Center over Several Years: Procedural and Clinical Outcomes. Medicina 2026, 62, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010204

Dursun H, Senturk B, Colluoglu T, Oktay C, Uysal H, Simsek HT, Karaoglan S, Tanriverdi Z, Kaya D. TAVI Performance at a Single Center over Several Years: Procedural and Clinical Outcomes. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010204

Chicago/Turabian StyleDursun, Huseyin, Bihter Senturk, Tugce Colluoglu, Cisem Oktay, Hacer Uysal, Husna Tuğçe Simsek, Sercan Karaoglan, Zulkif Tanriverdi, and Dayimi Kaya. 2026. "TAVI Performance at a Single Center over Several Years: Procedural and Clinical Outcomes" Medicina 62, no. 1: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010204

APA StyleDursun, H., Senturk, B., Colluoglu, T., Oktay, C., Uysal, H., Simsek, H. T., Karaoglan, S., Tanriverdi, Z., & Kaya, D. (2026). TAVI Performance at a Single Center over Several Years: Procedural and Clinical Outcomes. Medicina, 62(1), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010204