Therapeutic Outcomes of Fingolimod and Interferon Beta-1a in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Real-World Study from Jordan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Disability Assessment

3.3. Relapse Rate Comparison

3.4. Symptom Burden

3.5. Adverse Effects and Treatment Switching

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders, Stroke. Multiple Sclerosis; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023.

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, H. Global, regional, and national trends and burden of multiple sclerosis in adolescents and young adults. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1523456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; Van Der Mei, I.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarpour, P.; Khoshkish, S.; Abtahi, S.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Sahraian, M.A. Multiple sclerosis epidemiology in the Middle East and North Africa. Neuroepidemiology 2015, 44, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouhari, A.; Taheri, G.; Salari, M.; Moosazadeh, M.; Etemadifar, M. Multiple sclerosis epidemiology in Asia and Oceania. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 54, 103119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddadin, Y.B.; Ghanim, B.Y.; Mansour, R.A.; Shalabi, R.J.; Ennab, W.M.; Jaber, W.S.; Alnabaly, S.Y.; Al-Drabbea, N.M. The prevalence, epidemiology, patient well-being, adherence to therapy, and disease burden of multiple sclerosis in Jordan. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 11, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kofahi, R.M.; Kofahi, H.M.; Sabaheen, S.; Al Qawasmeh, M.; Momani, A.; Yassin, A.; Alhayk, K.; El-Salem, K. Prevalence of seropositivity of selected herpesviruses in patients with multiple sclerosis in northern Jordan. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klineova, S.; Lublin, F.D. Clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a028928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.L.; Cree, B.A.C. Treatment of multiple sclerosis. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 1380–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz Sand, I. Classification, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2015, 28, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omerhoca, S.; Yazici Akkas, S.; Kale Icen, N. Multiple sclerosis: Diagnosis and Differrential Diagnosis. Arch. Neuropsychiatry 2018, 55, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, A.; Chataway, J. Multiple sclerosis, a treatable disease. Clin. Med. 2017, 17, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auricchio, F.; Scavone, C.; Cimmaruta, D.; Di Mauro, G.; Capuano, A.; Sportiello, L.; Rafaniello, C. Drugs approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: Review of their safety profile. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2017, 16, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Mantia, L.; Tramacere, I.; Firwana, B.; Pacchetti, I.; Palumbo, R.; Filippini, G. Fingolimod for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, CD009371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, E.; Zhu, C.; Wei, R.; Ma, L.; Dong, X.; Li, R.; Sun, F.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, Y.; et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of disease-modifying therapies in relapsing multiple sclerosis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2023, 63, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laroni, A.; Brogi, D.; Morra, V.B.; Guidi, L.; Pozzilli, C.; Comi, G.; Lugaresi, A.; Turrini, R.; Raimondi, D.; Uccelli, A.; et al. Safety of the first dose of fingolimod for multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, M.; Sharmin, S.; Andersen, J.B.; Vukusic, S.; Casey, R.; Debouverie, M.; Edan, G.; Ciron, J.; Ruet, A.; De Sèze, J.; et al. Impact of methodological choices in comparative effectiveness studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2022, 22, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of South Florida. New MS Patient Questionnaire; University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Okwuokenye, M.; Zhang, A.; Pace, A.; Peace, K.E. Number needed to treat in multiple sclerosis clinical trials. Neurol. Ther. 2017, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamout, B.I.; Assaad, W.; Tamim, H.; Mrabet, S.; Goueider, R. Epidemiology and phenotypes of multiple sclerosis in the Middle East North Africa region. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2020, 6, 2055217319841881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanu, A.; Aschmann, H.E.; Kesselring, J.; Puhan, M.A. Fingolimod versus interferon beta-1a: Benefit–harm assessment based on TRANSFORMS data. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2022, 8, 20552173221117784. [Google Scholar]

- Khatri, B.; Barkhof, F.; Comi, G.; Hartung, H.P.; Kappos, L.; Montalban, X.; Pelletier, J.; Stites, T.; Wu, S.; Holdbrook, F.; et al. Comparison of fingolimod with interferon beta-1a in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, T.; Arnold, D.L.; Banwell, B.; Brück, W.; Ghezzi, A.; Giovannoni, G.; Greenberg, B.; Krupp, L.; Rostásy, K.; Tardieu, M.; et al. Trial of fingolimod versus interferon beta-1a in pediatric multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alroughani, R.; AlKawi, Z.; Hassan, A.; Al Otaibi, H.; Mujtaba, A.; Al Atat, R.; Riachi, N.; Akkawi, N.; Koussa, S.; Inshasi, J.; et al. Real-world retrospective study of effectiveness and safety of fingolimod in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis in the Middle East and North Africa (FINOMENA). Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2021, 203, 106576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamout, B.I.; Zeineddine, M.M.; Tamim, H.; Khoury, S.J. Safety and efficacy of fingolimod in clinical practice. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015, 289, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khdair, S.I.; Waleed, M.; Hammad, A.M.; Al-Khareisha, L.; Jaber, T.; Ayash, M.; Hall, F.S. Cytokine gene expression and treatment impact on MRI outcomes in Jordanian patients with multiple sclerosis. Life 2025, 15, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Dayem, M.A.; Shaker, M.E.; Gameil, N.M. Impact of interferon β-1b, interferon β-1a and fingolimod therapies on serum interleukins-22, 32α and 34 concentrations in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 337, 577062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Keilani, M.S.; Almomani, B.A. Medication adherence to disease-modifying therapies among Jordanian patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 31, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabbadi, I.; Al-Ajlouny, S.; Alsoud, Y.; BaniHani, A.; Arar, B.A.; Massad, E.M.; Muflih, S.; Shawawrah, M. The cost-of-illness of multiple sclerosis in Jordan. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2025, 25, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Baxter, D.C.; Limone, B.; Roberts, M.S.; Coleman, C.I. Cost-effectiveness of fingolimod versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. J. Med. Econ. 2012, 15, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.H.; Hersh, C.M.; Morten, P.; Kusel, J.; Lin, F.; Cave, J.; Varga, S.; Herrera, V.; Ko, J.J. The Impact of Price Reductions After Loss of Exclusivity in a Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Fingolimod Versus Interferon Beta-1a for the Treatment of Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2019, 25, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 122 (100) |

| Age | |

| <20 | 4 (3.3) |

| 21–30 | 32 (26.2) |

| 31–40 | 49 (40.2) |

| 41–50 | 26 (21.3) |

| >50 | 11 (9) |

| Age at onset | |

| Median (Range) | 27 (14–54) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 32 (26.2) |

| Female | 90 (73.8) |

| Smoking | |

| Current or former smoker | 40 (32.7%) |

| Never smoker | 82 (67.2%) |

| Level of education | |

| College or higher | 65 (53.3) |

| High school | 44 (36.1) |

| Less than high school | 13 (10.6) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 51 (41.8) |

| Unemployed | 71 (58.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 56(45.9) |

| Married | 66(54.1) |

| Initial presentation | |

| Visual | 43 (35.2) |

| Motor | 6 (4.9) |

| Sensory/pain | 59 (48.4) |

| Dizziness/imbalance | 10 (8.2) |

| Others | 4 (3.3) |

| Disability (EDSS) * | |

| 0–3.5 | 107 (92.2) |

| 4–5.5 | 8 (6.9) |

| 6–10 | 1 (0.9) |

| Current medication | |

| Fingolimod | 87 (71.3) |

| Interferon | 33 (27) |

| Others | 2 (1.6) |

| ARR | |

| Mean (CI) | 0.44 (0.33–0.55) |

| Family history of MS | |

| Yes | 19 (15.5) |

| No | 103 (84.5) |

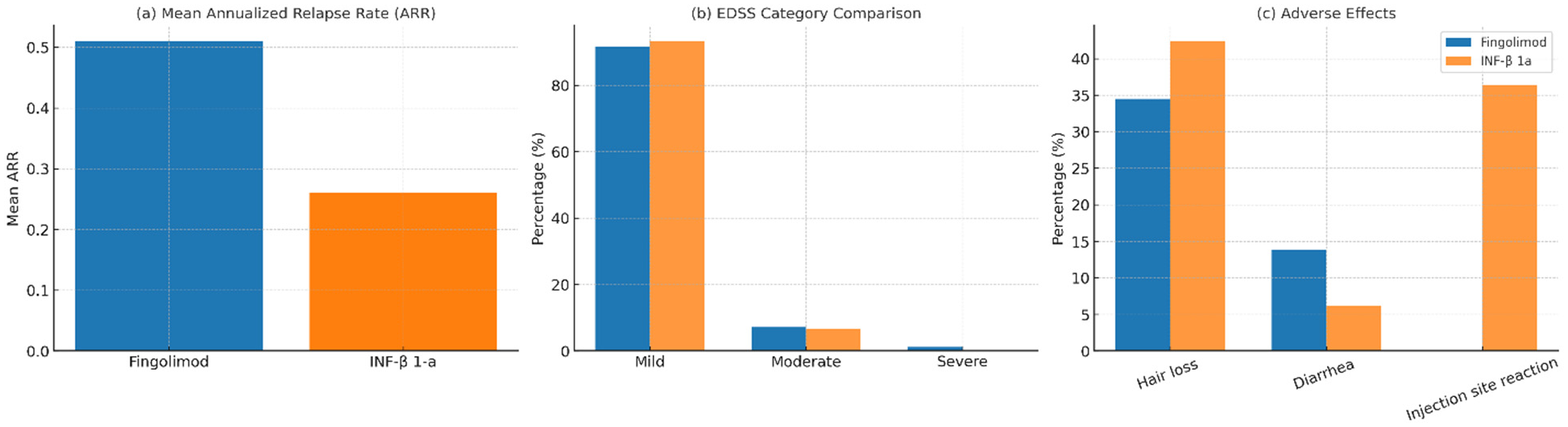

| Variable | Number (%) | Fingolimod | INF-β 1-a | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 120 (100) | 87 (72.5) | 33 (27.5) | |

| EDDS * | 114 (100) | 1 | ||

| Mild | 105 (92.1) | 77 (91.7) | 28 (93.3) | |

| Moderate | 8 (7) | 6 (7.1) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Severe | 1(0.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| ARR | 0.016 | |||

| Mean | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.26 | |

| Visual symptoms | 0.150 | |||

| 0 | 46 (38.3) | 33 (37.9) | 13 (39.4) | |

| 1–2 | 38 (31.7) | 24 (27.6) | 14 (42.4) | |

| >2 | 36 (30.0) | 30(34.5) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Bowel/bladder symptoms | 0.322 | |||

| 0 | 68 (56.7) | 52 (59.8) | 16 (48.5) | |

| 1–2 | 38 (31.7) | 24 (27.6) | 14 (42.4) | |

| >2 | 14 (11.7) | 11 (12.6) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Pyramidal symptoms | 0.592 | |||

| 0 | 39 (32.5) | 29 (33.3) | 10 (30.3) | |

| 1–2 | 32 (26.7) | 21 (24.1) | 11 (33.3) | |

| >2 | 49 (40.8) | 37 (42.5) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Sensory symptoms | 0.742 | |||

| 0 | 28 (23.3) | 19 (21.8) | 9 (27.3) | |

| 1–2 | 50 (41.7) | 36 (41.4) | 14 (42.4) | |

| >2 | 42 (35.0) | 32 (36.8) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Sexual symptoms | 0.281 | |||

| Yes | 10 (8.3) | 9 (10.3) | 1 (3.0) | |

| No | 110 (91.7) | 78 (89.7) | 32 (97.0) | |

| Number of side effects (0–2) ** | 0.024 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 0.58 ± 0.60 | 0.49 ± 0.58 | 0.82 ± 0.63 | |

| Hair loss | 0.420 | |||

| Yes | 44 (36.7) | 30 (34.5) | 14 (42.4) | |

| No | 76 (63.7) | 57 (65.5) | 19 (57.6) | |

| Diarrhea | 0.345 | |||

| Yes | 14 (11.7) | 12 (13.8) | 2 (6.1) | |

| No | 106 (88.3) | 75 (86.2) | 31 (93.9) | |

| Injection site reaction | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 12 (10) | 0 (0) | 12 (36.4) | |

| No | 108 (90) | 87 (100) | 21 (63.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al Anber, A.; Abu Al Karsaneh, O.; Abuquteish, D.; Abdallah, O.; Issa, M.A.; Sa’adeh, M.; Kilani, D. Therapeutic Outcomes of Fingolimod and Interferon Beta-1a in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Real-World Study from Jordan. Medicina 2026, 62, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010203

Al Anber A, Abu Al Karsaneh O, Abuquteish D, Abdallah O, Issa MA, Sa’adeh M, Kilani D. Therapeutic Outcomes of Fingolimod and Interferon Beta-1a in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Real-World Study from Jordan. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010203

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Anber, Arwa, Ola Abu Al Karsaneh, Dua Abuquteish, Osama Abdallah, Mohammad A. Issa, Mohammad Sa’adeh, and Dena Kilani. 2026. "Therapeutic Outcomes of Fingolimod and Interferon Beta-1a in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Real-World Study from Jordan" Medicina 62, no. 1: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010203

APA StyleAl Anber, A., Abu Al Karsaneh, O., Abuquteish, D., Abdallah, O., Issa, M. A., Sa’adeh, M., & Kilani, D. (2026). Therapeutic Outcomes of Fingolimod and Interferon Beta-1a in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Real-World Study from Jordan. Medicina, 62(1), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010203