Paradoxical Effect of Obesity on Survival Outcomes in Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Enzalutamide and Abiraterone

Abstract

1. Introduction

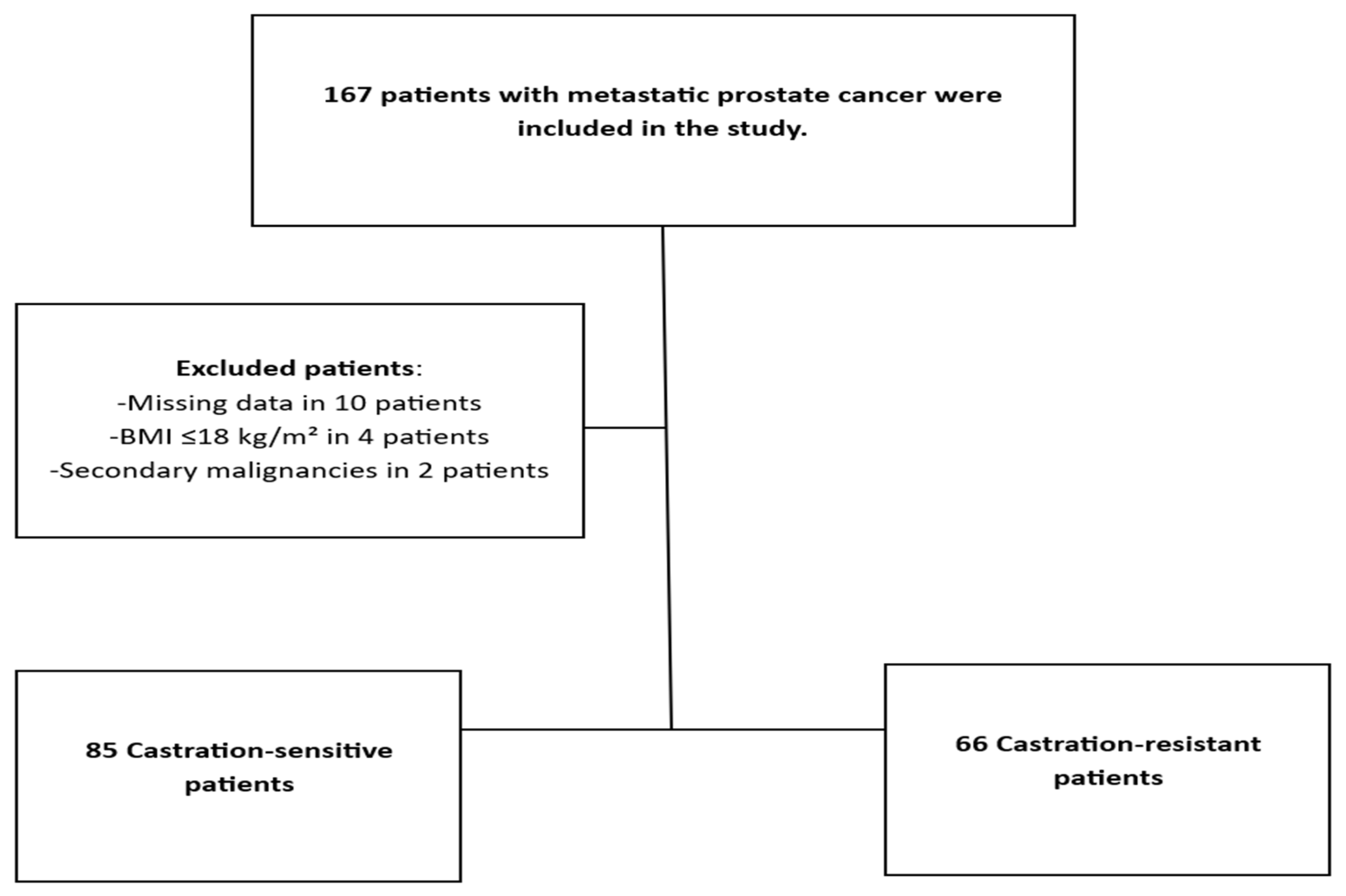

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

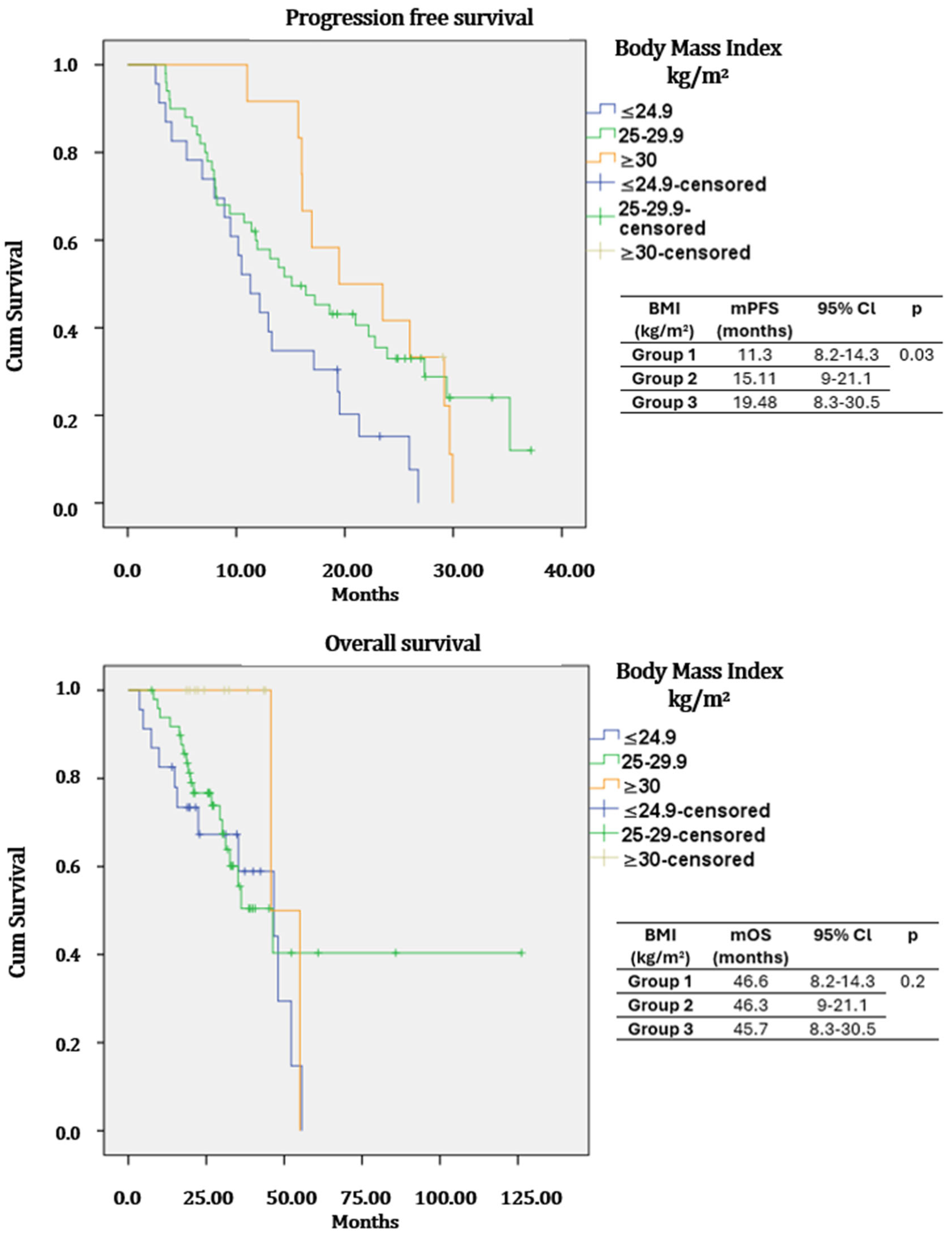

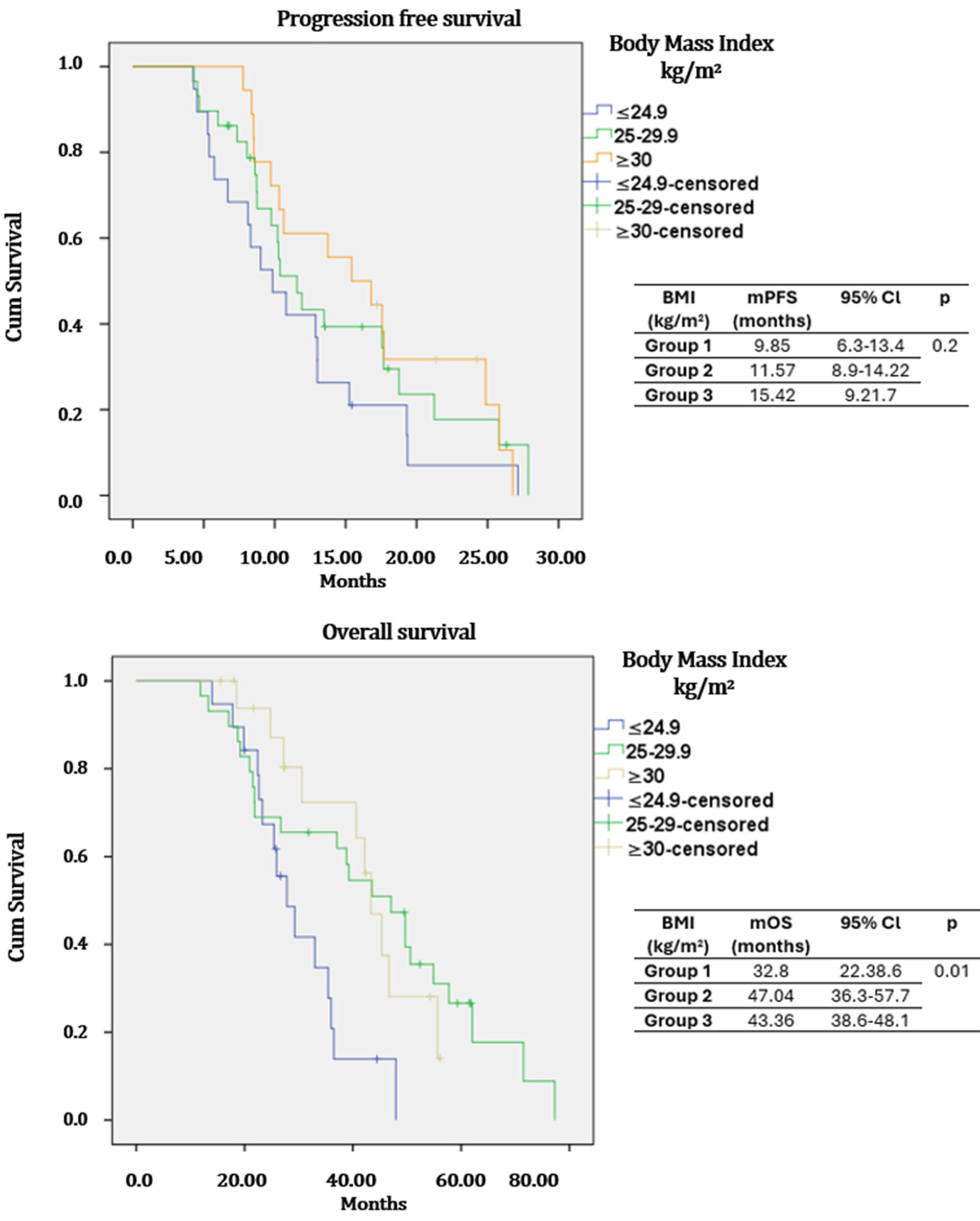

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSPC | Castration-sensitive prostate cancer |

| CRPC | Castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| BMI | Body Mass İndex |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| OS | overall survival |

| ECOG-PS | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score |

| ADT | Androgen deprivation therapy |

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. In Report of a WHO Consultation; World Health Organization technical report series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; Volume 894, pp. 1–253. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh, E.; Patlak, M.; Nass, S.J. Incorporating Weight Management and Physical Activity Throughout the Cancer Care Continuum: Proceedings of a Workshop; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Kruper, L.; Dieli-Conwright, C.M.; Mortimer, J.E. The impact of obesity on breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Morley, T.S.; Kim, M.; Clegg, D.J.; Scherer, P.E. Obesity and cancer—Mechanisms underlying tumour progression and recurrence. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, V.; Guérard, A.; Mazerolles, C.; Le Gonidec, S.; Toulet, A.; Nieto, L.; Zaidi, F.; Majed, B.; Garandeau, D.; Socrier, Y.; et al. Periprostatic adipocytes act as a driving force for prostate cancer progression in obesity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, B.D.; Goncalves, M.D.; Cantley, L.C. Obesity and cancer mechanisms: Cancer metabolism. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4277–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, K.; Carton, M.; Dieras, V.; Heudel, P.E.; Brain, E.; D’hondt, V.; Mailliez, A.; Patsouris, A.; Mouret-Reynier, M.A.; Goncalves, A.; et al. Impact of body mass index on overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast 2021, 55, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plonski, J.J.S.; Fernández-Pello, S.; Jiménez, L.R.; Rodríguez, I.G.; Calvar, L.A.; Villamil, L.R. Impact of body mass index on survival of metastatic renal cancer. J. Kidney Cancer VHL 2021, 8, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcio, F.; Sasso, G.; Liguori, I.; Ferro, G.; Russo, G.; Cellurale, M.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; et al. The reverse metabolic syndrome in the elderly: Is it a “catabolic” syndrome? Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar, S.S.; Williams, G.R.; Muss, H.B.; Nishijima, T.F. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in adults with solid tumours: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 57, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmach-Mardas, M.; Warchoł, W.; Garczyk, A.; Warchoł, E.; Korczak, J.; Litwiniuk, M.; Brajer-Luftmann, B.; Mardas, M. Influence of androgen deprivation therapy on the development of sarcopenia in patients with prostate cancer: A systematic review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A.C.; Howard, L.E.; Sun, S.X.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Kane, C.J.; Aronson, W.J.; Terris, M.K.; Amling, C.L.; Freedland, S.J. Obesity and prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy: Results from the SEARCH database. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017, 20, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedland, S.J.; Wen, J.; Wuerstle, M.; Shah, A.; Lai, D.; Moalej, B.; Atala, C.; Aronson, W.J. Obesity is a significant risk factor for prostate cancer at the time of biopsy. Urology 2008, 72, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffoni, M.; Volta, A.D.; Valcamonico, F.; Bergamini, M.; Caramella, I.; D’aPollo, D.; Zivi, A.; Procopio, G.; Sepe, P.; Del Conte, G.; et al. Total and regional changes in body composition in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer patients randomized to receive androgen deprivation + enzalutamide ± zoledronic acid: The BONENZA study. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Clements, S.; McWilliam, A.; Green, A.; Descamps, T.; Oing, C.; Gillessen, S. Influence of abiraterone and enzalutamide on body composition in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2020, 25, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, S.; Ye, D.; Zhu, Y. Combination of body mass index and albumin predicts survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with abiraterone: A post hoc analysis of two randomized trials. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 6697–6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morote, J.; Aguilar, A.; Planas, J.; Trilla, E. Definition of castrate resistant prostate cancer: New insights. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Carducci, M.; Liu, G.; Jarrard, D.F.; Eisenberger, M.; Wong, Y.-N.; Hahn, N.; Kohli, M.; Cooney, M.M.; et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fizazi, K.; Tran, N.; Fein, L.; Matsubara, N.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ye, D.; Feyerabend, S.; Protheroe, A.; et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Goodwin, P.J.; Chlebowski, R.T. Obesity and cancer: Insights for clinicians. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4197–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, D.I.; Freedland, S.J. Metabolic risk factors in prostate cancer. Cancer 2011, 117, 2020–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, M.Z. Letter to the editor regarding the article “Are older patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving optimal care? A population-based study”. Acta Oncol. 2022, 61, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman-Esquivel, J.; Mendoza-Hernandez, M.A.; Tiburcio-Jimenez, D.; Avila-Zamora, O.N.; Delgado-Enciso, J.; De-Leon-Zaragoza, L.; Casarez-Price, J.C.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, I.P.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L.; Meza-Robles, C.; et al. Decreased biochemical progression in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer using a novel mefenamic acid anti-inflammatory therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 19, 4151–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Features | Castration-Sensitive Group (n = 85) | Castration-Resistant Group (n = 66) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≤70 | 35 (41.2%) | 33 (50%) |

| >70 | 50 (51.8%) | 33 (50%) | |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | <25 | 23 (27.1%) | 4 (6.1%) |

| 25–29.9 | 50 (58.8%) | 36 (54.5%) | |

| ≥30 | 12 (14.1%) | 26 (39.4%) | |

| ECOG-PS | 0 | 14 (16.5%) | 19 (28.8%) |

| 1 | 51 (60%) | 29 (43.9%) | |

| ≥2 | 20 (23.5%) | 18 (27.3%) | |

| Statin use | No | 66 (77.6%) | 49 (74.2%) |

| Yes | 19 (22.4%) | 17 (25.8%) | |

| Comorbidity | No | 39 (45.9%) | 30 (45.5%) |

| Yes | 46 (54.1%) | 36 (54.5%) | |

| Gleason score | ≤8 | 20 (23.5%) | 19 (28.8%) |

| 9–10 | 65 (76.5%) | 47 (71.2%) | |

| Primary surgery | No | 74 (87.1%) | 56 (84.8%) |

| Yes | 11 (12.9%) | 10 (15.2%) | |

| De novo metastatic | No | 26 (30.6%) | 23 (34.8%) |

| Yes | 59 (69.4%) | 43 (65.2%) | |

| Disease volume * | Low | 22 (25.9%) | 9 (13.6%) |

| High | 63 (74.1%) | 57 (86.4%) | |

| Disease risk ** | Low risk | 21 (24.7%) | 9 (13.6%) |

| High risk | 64 (75.3%) | 57 (86.4%) | |

| Medical treatment | Abiraterone acetate | 46 (54.1%) | 33 (50%) |

| Enzalutamide | 39 (45.9%) | 33 (50%) | |

| Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) | Medical | 83 (97.6%) | 63 (95.5%) |

| Surgery | 2 (2.4%) | 3 (4.5%) | |

| Features | Castration-Sensitive Group | Castration-Resistant Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| Group 1 (≤24.9) | Group 2 (25–29.9) | Group 3 (≥30) | p | Group 1 (≤24.9) | Group 2 (25–29.9) | Group 3 (≥30) | p | ||

| Age (years) | ≤70 | 11 (47.8%) | 14 (34%) | 7 (58.3%) | 0.23 | 9 (47.4%) | 14 (48.3%) | 10 (55.6%) | 0.85 |

| >70 | 12 (52.2%) | 33 (66%) | 5 (41.7%) | 10 (52.6%) | 15 (51.7%) | 8 (44.4%) | |||

| ECOG-PS | 0–1 | 19(82.6%) | 35 (70%) | 11(91.7%) | 0.075 | 11(57.9%) | 20(68.9%) | 9 (50%) | 0.62 |

| 2 | 4 (17.4%) | 15 (30%) | 1 (8.3%) | 8 (42.1%) | 9 (31%) | 9 (50%) | |||

| Statin use | No | 18 (78.3%) | 38 (76%) | 10 (83.3%) | 0.85 | 14 (73.7%) | 21 (72.4%) | 14 (77.8%) | 0.91 |

| Yes | 5 (21.7%) | 12 (24%) | 2 (16.7%) | 5 (26.3%) | 8 (27.6%) | 4 (22.2%) | |||

| Comorbidity | No | 13 (56.5%) | 21 (42%) | 5 (41.7%) | 0.48 | 10 (52.6%) | 12 (41.4%) | 8 (44.4%) | 0.74 |

| Yes | 10 (43.5%) | 29 (58%) | 7 (58.3%) | 9 (47.4%) | 17 (58.6%) | 10 (56.6%) | |||

| Gleason score | ≤8 | 5 (21.7%) | 12 (24%) | 3 (25%) | 0.64 | 5 (26.3%) | 10 (34.5%) | 4 (22.2%) | 0.64 |

| 9–10 | 18 (78.3%) | 38 (76%) | 9 (75%) | 14 (73.7%) | 19 (65.5%) | 14 (77.8%) | |||

| Primary surgery | No | 22 (95.7%) | 43 (86%) | 9 (75%) | 0.21 | 17 (89.5%) | 25 (86.2%) | 14 (77.8%) | 0.58 |

| Yes | 1 (4.3%) | 7 (14%) | 3 (25%) | 2 (10.5%) | 4 (13.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | |||

| De novo metastatic | No | 5 (21.7%) | 13 (26%) | 8 (66.7%) | 0.13 | 5 (26.3%) | 11 (37.9%) | 17 (38.9%) | 0.65 |

| Yes | 18 (78.3%) | 37 (74%) | 4 (33.3%) | 14 (73.7%) | 18 (62.1%) | 11 (61.1%) | |||

| Disease volume * | Low | 5 (21.7%) | 10 (20%) | 7 (58.3%) | 0.20 | 3 (15.8%) | 4 (13.8%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0.91 |

| High | 18 (78.3%) | 40 (80%) | 5 (41.7%) | 16 (84.2%) | 25 (86.2%) | 16 (88.9%) | |||

| Disease risk ** | Low risk | 4 (17.4%) | 10 (20%) | 7 (58.3%) | 0.14 | 3 (15.8%) | 4 (13.8%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0.91 |

| High risk | 19 (82.6%) | 40 (80%) | 5 (41.7%) | 16 (84.2%) | 25 (86.2%) | 16 (88.9%) | |||

| Medical treatment | Abiraterone acetate | 13 (56.5%) | 31 (92%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0.18 | 11 (57.9%) | 13 (44.8%) | 9 (50%) | 0.67 |

| Enzalutamide | 10 (43.5%) | 19 (38%) | 10 (83.3%) | 8 (42.1%) | 16 (55.2%) | 9 (50%) | |||

| Androgen deprivation therapy | Medical | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.78 | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0.84 |

| Surgery | 23 (100%) | 48 (96%) | 12 (100%) | 18 (94.7%) | 28 (96.6%) | 17 (94.4%) | |||

| Progression-Free Survival | Castration-Sensitive Group | ||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | ||

| Age | ≤70 vs. >70 | 0.68 | 0.41–1.12 | 0.13 | - | - | - |

| ECOG-PS | 0 | Reference | 0.08 | Reference | 0.029 | ||

| 1 | 1.71 | 0.79–3.66 | 0.16 | 2.73 | 1.22–6.10 | 0.014 | |

| 2 | 2.52 | 1.09–5.83 | 0.03 | 3.06 | 1.28–7.29 | 0.011 | |

| BMI | ≤24.9 | Reference | 0.036 | Reference | 0.09 | ||

| 25–29.9 | 0.50 | 0.29–0.88 | 0.017 | 0.70 | 0.22–1.12 | 0.20 | |

| ≥30 | 0.64 | 0.31–0.97 | 0.043 | 0.67 | 0.20–0.99 | 0.04 | |

| Statin use | No vs. Yes | 0.71 | 0.41–1.24 | 0.24 | - | - | - |

| Comorbidity | No vs. Yes | 0.72 | 0.43–1.16 | 0.17 | - | - | - |

| Gleason score | ≤8 vs. 9–10 | 1.38 | 0.79–2.41 | 0.25 | - | - | - |

| Disease volume * | Low vs. High | 0.41 | 0.23–0.75 | 0.004 | 0.54 | 0.30–0.85 | 0.01 |

| De novo metastatic | No vs. Yes | 1.47 | 0.89–2.44 | 0.13 | - | - | - |

| Overall Survival | Castration-Sensitive Group | ||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | ||

| Age | ≤70 vs. >70 | 0.70 | 0.34–1.43 | 0.33 | - | - | - |

| ECOG-PS | 0 | Reference | 0.08 | Reference | 0.07 | ||

| 1 | 1.88 | 0.43–8.18 | 0.39 | 2.70 | 0.62–4.87 | 0.17 | |

| 2 | 2.85 | 0.86–7.23 | 0.07 | 3.90 | 1.08–5.24 | 0.03 | |

| BMI | ≤24.9 | Reference | 0.24 | Reference | 0.18 | ||

| 25–29.9 | 0.73 | 0.35–1.52 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 0.30–1.38 | 0.26 | |

| ≥30 | 0.68 | 0.35–1.26 | 0.09 | 0.62 | 0.27–1.21 | 0.08 | |

| Statin use | No vs. Yes | 0.78 | 0.37–1.65 | 0.52 | - | - | - |

| Comorbidity | No vs. Yes | 0.78 | 0.38–1.59 | 0.5 | - | - | - |

| Gleason score | ≤8 vs. 9–10 | 1.52 | 1.09–2.24 | 0.02 | 1.50 | 1.01–2.71 | 0.03 |

| Disease volume * | Low vs. High | 0.48 | 0.26–0.89 | 0.028 | 0.75 | 0.41–0.96 | 0.04 |

| De novo metastatic | No vs. Yes | 1.22 | 0.78–1.88 | 0.21 | - | - | - |

| Progression-Free Survival | Castration-Resistance Group | ||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | ||

| Age | ≤70 vs. >70 | 1.04 | 0.58–1.71 | 0.98 | - | - | - |

| ECOG-PS | 0 | Reference | 0.18 | - | - | - | |

| 1 | 0.37 | 0.18–1.64 | 0.19 | - | - | - | |

| 2 | 1.31 | 0.75–2.30 | 0.33 | - | - | - | |

| BMI | ≤24.9 | Reference | 0.18 | Reference | 0.2 | ||

| 25–29.9 | 0.77 | 0.41–1.47 | 0.44 | 0.90 | 0.55–190 | 0.81 | |

| ≥30 | 0.52 | 0.26–1.04 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.15–1.21 | 0.15 | |

| Statin use | No vs. Yes | 0.75 | 0.55–1.42 | 0.74 | - | - | - |

| Comorbidity | No vs. Yes | 0.48 | 0.30–1.25 | 0.55 | - | - | - |

| Gleason score | ≤8 vs. 9–10 | 0.33 | 0.16–0.66 | 0.002 | 2.60 | 1.27–5.31 | 0.008 |

| Disease volume * | Low vs. High | 0.55 | 0.35–0.89 | 0.01 | 2.25 | 0.73–6.97 | 0.15 |

| De novo metastatic | No vs. Yes | 0.64 | 0.35–1.17 | 0.15 | - | - | - |

| Overall Survival | Castration-Resistant Group | ||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | ||

| Age | ≤70 vs. >70 | 0.56 | 0.30–1.02 | 0.06 | 1.45 | 0.70–2.99 | 0.32 |

| ECOG-PS | 0 | Reference | 0.06 | Reference | 0.54 | ||

| 1 | 3.50 | 0.47–6.05 | 0.22 | 1.11 | 0.70–4.42 | 0.86 | |

| 2 | 6.32 | 0.82–8.27 | 0.07 | 1.21 | 0.81–4.9 | 0.87 | |

| BMI | ≤24.9 | Reference | 0.33 | Reference | 0.71 | ||

| 25–29.9 | 0.67 | 0.34–1.32 | 0.02 | 0.79 | 0.40–1.56 | 0.50 | |

| ≥30 | 0.56 | 0.25–1.27 | 0.16 | 0.71 | 0.25–1.72 | 0.45 | |

| Statin use | No vs. Yes | 0.78 | 0.55–1.20 | 0.48 | - | - | - |

| Comorbidity | No vs. Yes | 0.85 | 0.64–1.48 | 0.69 | - | - | - |

| Gleason score | ≤8 vs. 9–10 | 0.52 | 0.26–1.00 | 0.052 | 1.71 | 1.40–2.98 | 0.06 |

| Disease volume * | Low vs. High | 0.42 | 0.22–0.73 | 0.013 | 2.47 | 1.63–6.70 | 0.019 |

| De novo metastatic | No vs. Yes | 0.45 | 0.15–1.11 | 0.36 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kaya, B.E.; Koçak, M.Z.; Yıldız, O.; Aykut, T.; Gürbüz, A.F.; Genç, Ö.; Karakurt Eryılmaz, M.; Araz, M.; Artaç, M. Paradoxical Effect of Obesity on Survival Outcomes in Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Enzalutamide and Abiraterone. Medicina 2026, 62, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010202

Kaya BE, Koçak MZ, Yıldız O, Aykut T, Gürbüz AF, Genç Ö, Karakurt Eryılmaz M, Araz M, Artaç M. Paradoxical Effect of Obesity on Survival Outcomes in Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Enzalutamide and Abiraterone. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010202

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaya, Bahattin Engin, Mehmet Zahid Koçak, Oğuzhan Yıldız, Talat Aykut, Ali Fuat Gürbüz, Ömer Genç, Melek Karakurt Eryılmaz, Murat Araz, and Mehmet Artaç. 2026. "Paradoxical Effect of Obesity on Survival Outcomes in Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Enzalutamide and Abiraterone" Medicina 62, no. 1: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010202

APA StyleKaya, B. E., Koçak, M. Z., Yıldız, O., Aykut, T., Gürbüz, A. F., Genç, Ö., Karakurt Eryılmaz, M., Araz, M., & Artaç, M. (2026). Paradoxical Effect of Obesity on Survival Outcomes in Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Enzalutamide and Abiraterone. Medicina, 62(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010202