MRI Diffusion Imaging as an Additional Biomarker for Monitoring Chemotherapy Efficacy in Tumors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Patient Population

2.3. MRI Acquisition

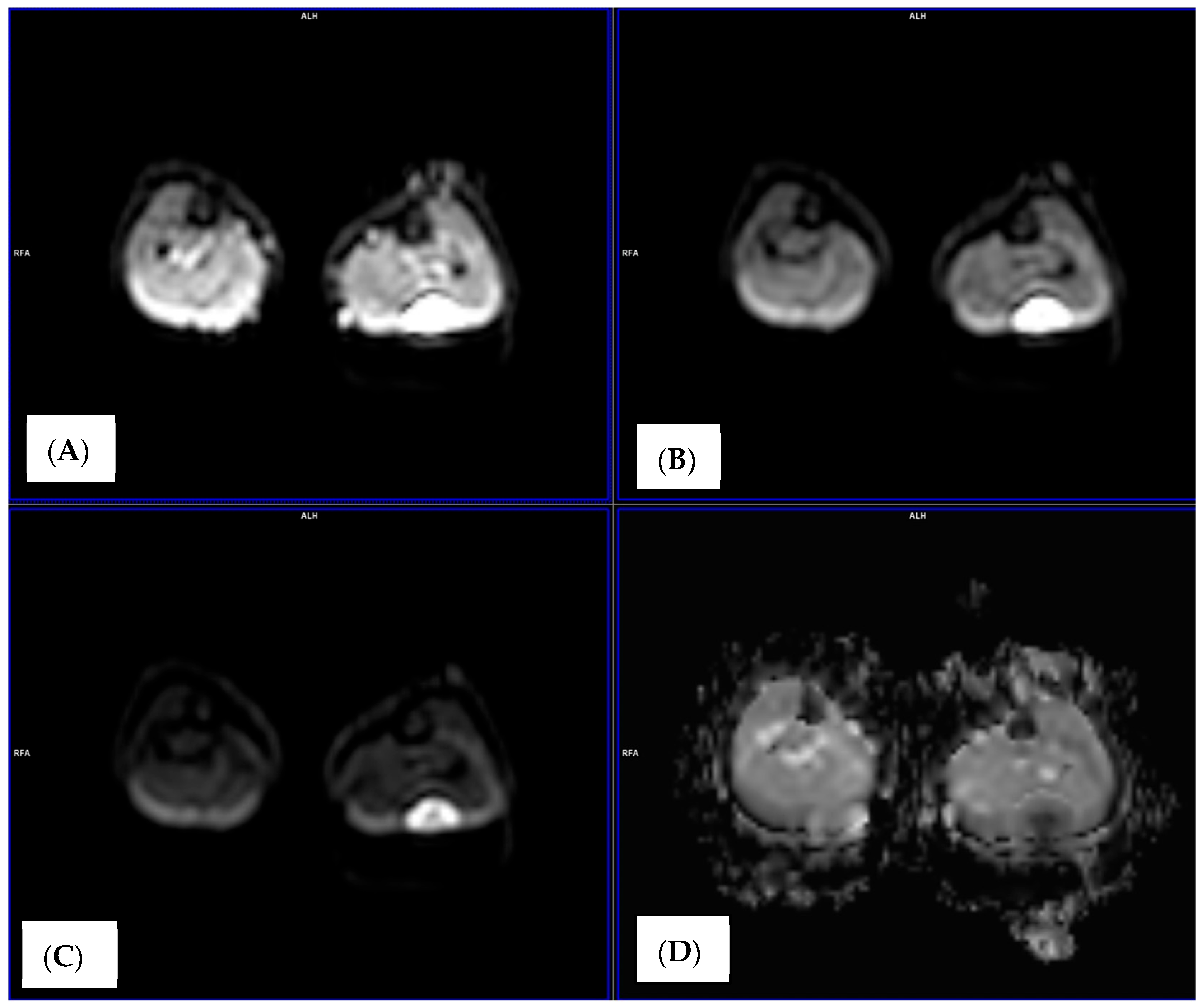

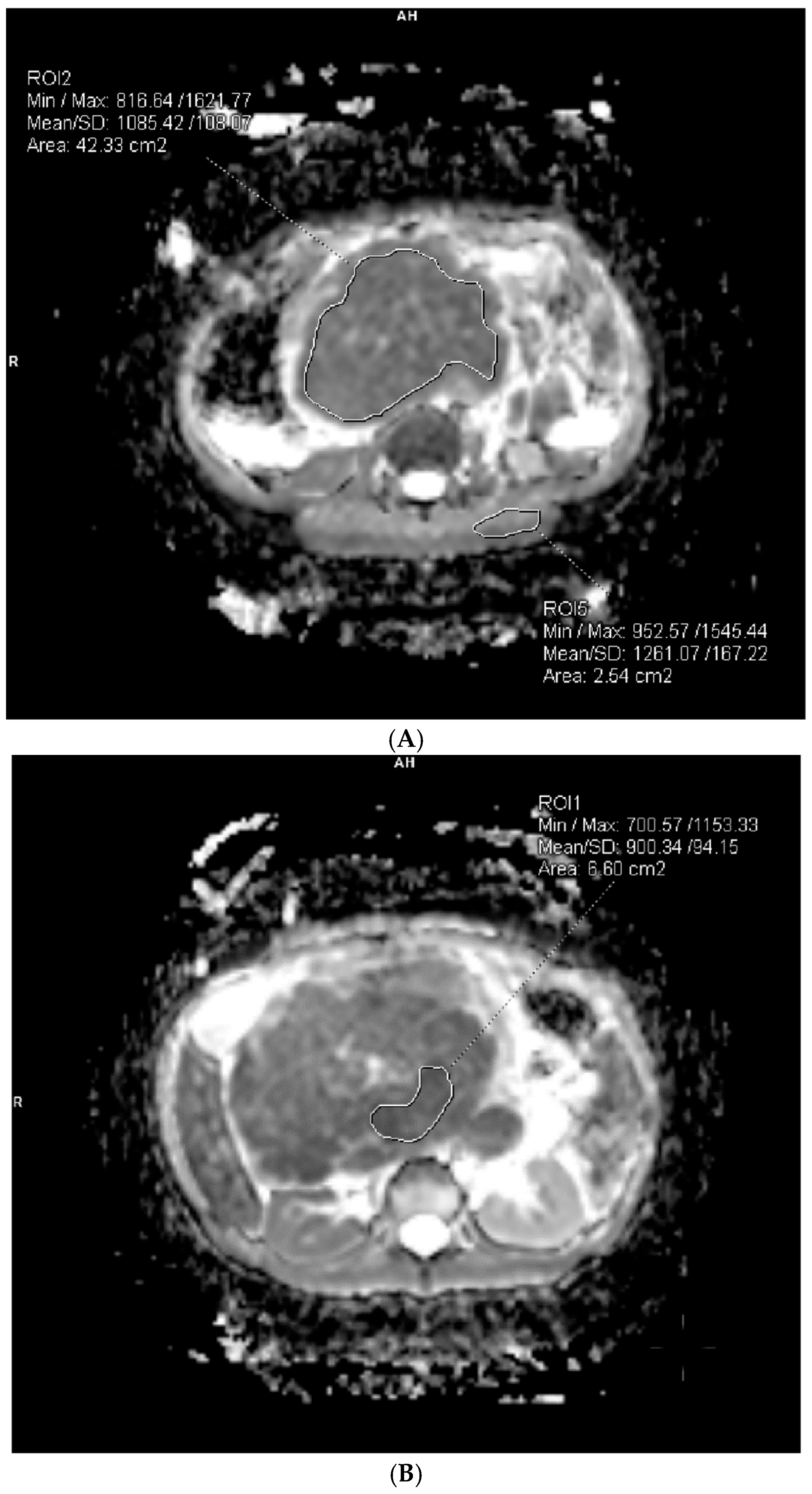

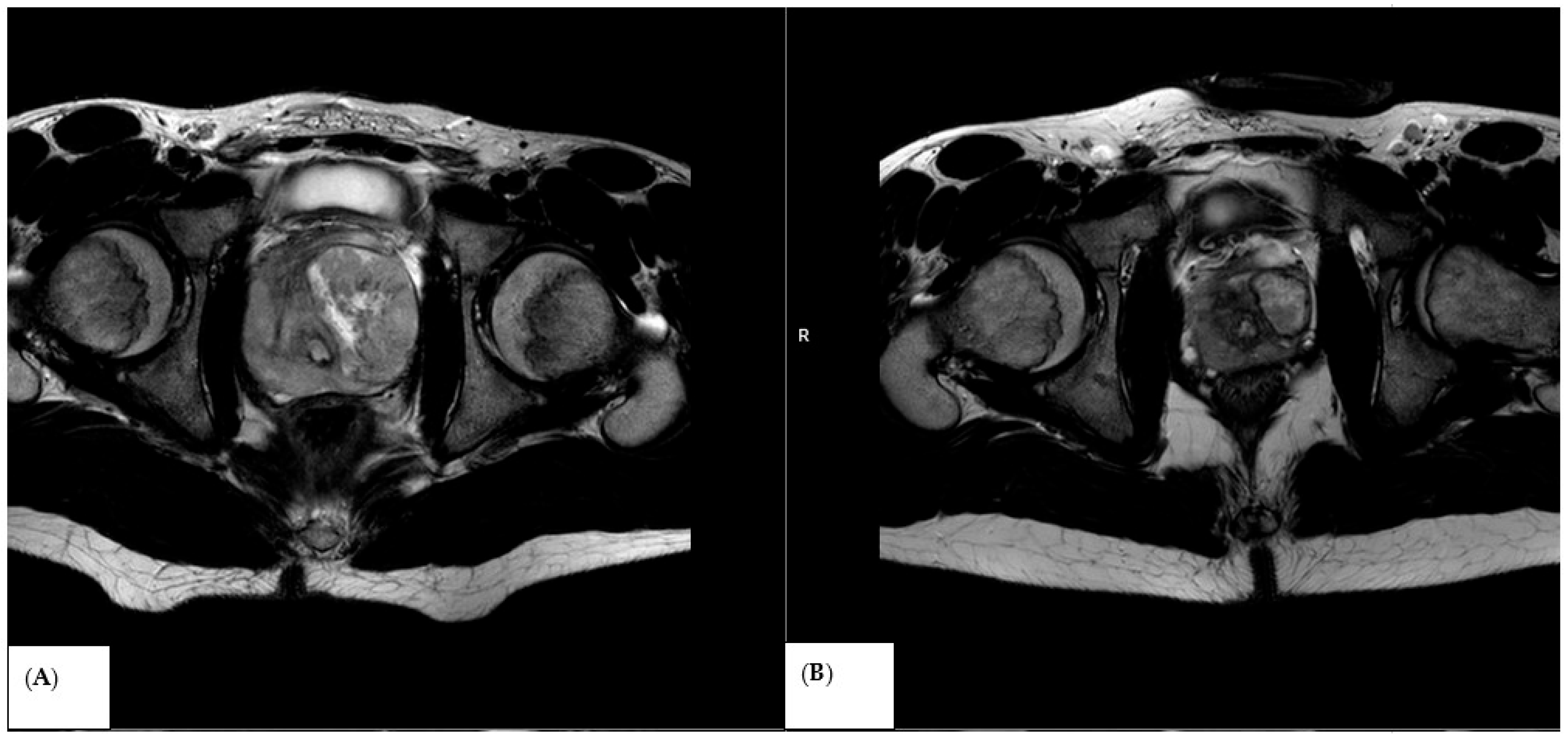

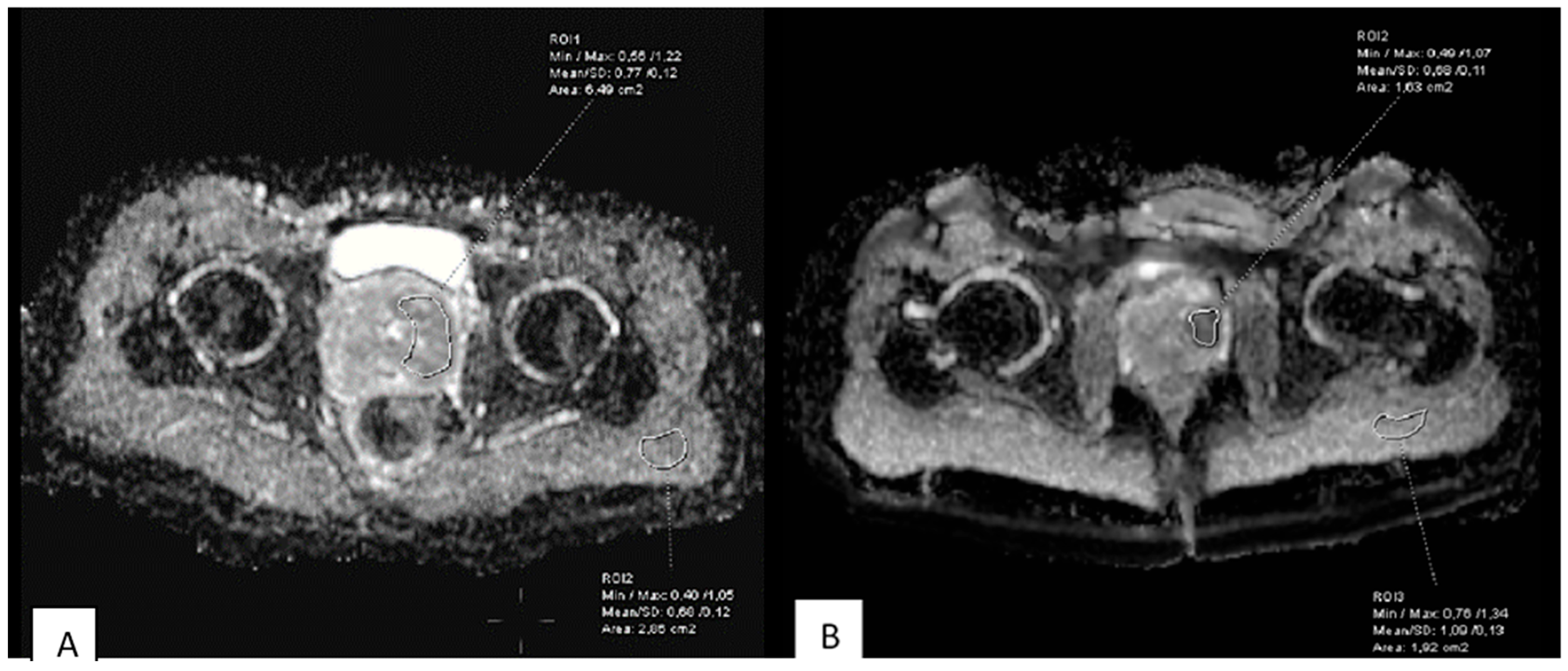

2.4. Image Analysis and ADC Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Diffusion Characteristics

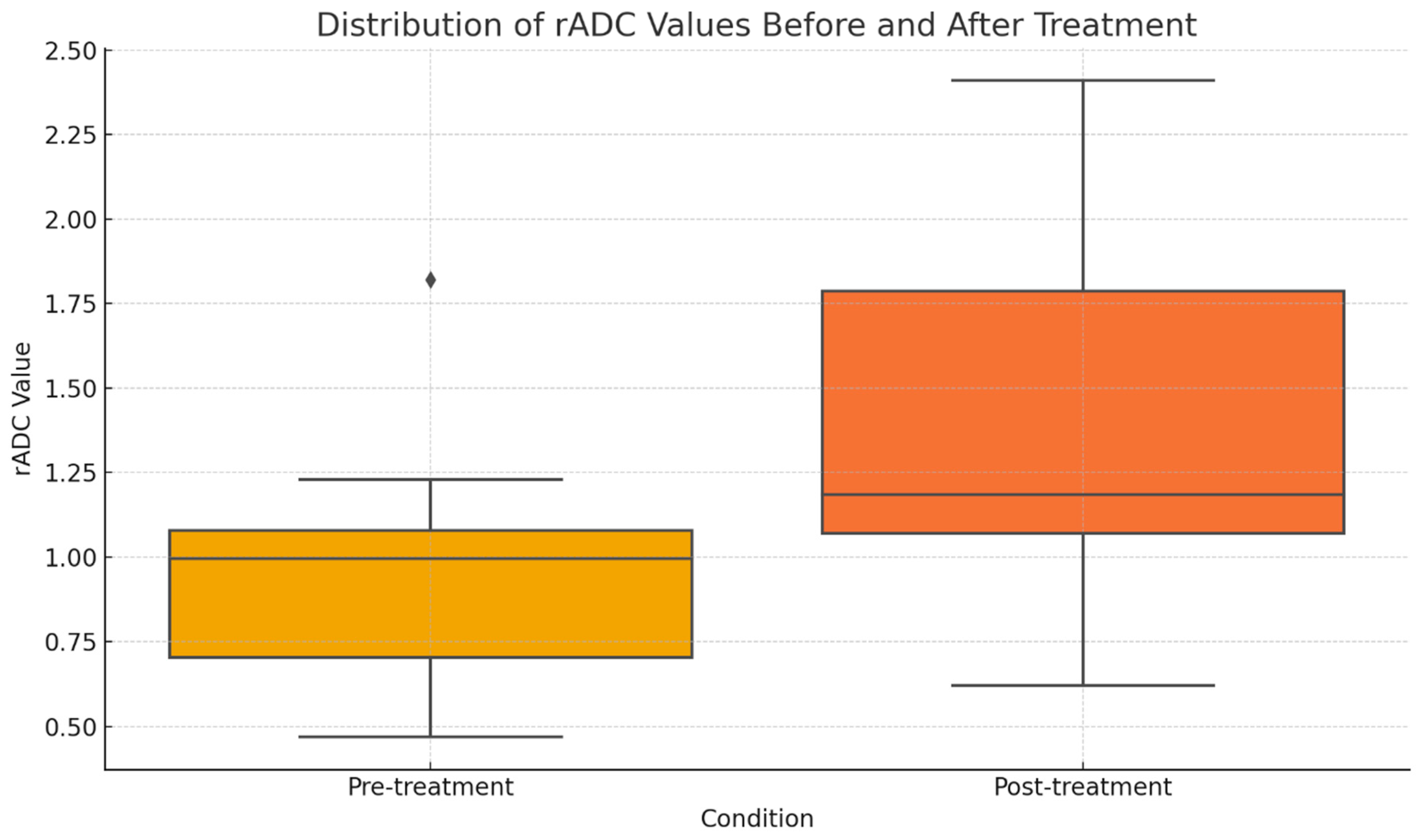

3.2. ADC Changes After Chemotherapy

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, H.Y.; Chung, H.W.; Yoon, M.A.; Chee, C.G.; Kim, W.; Lee, J.S. Enhancing local recurrence detection in patients with high-grade soft tissue sarcoma: Value of short-term Ultrasonography added to post-operative MRI surveillance. Cancer Imaging 2024, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, D.S.; Spunt, S.L.; Skapek, S.X. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: Soft tissue sarcomas. Pediatr. Blood. Cancer 2013, 60, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koscielniak, E.; Morgan, M.; Treuner, J. Soft Tissue Sarcoma in Children Prognosis and Management. Pediatr. Drugs 2002, 4, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingley, K.M.; Cohen-Gogo, S.; Gupta, A.A. Systemic therapy in pediatric-type soft-tissue sarcoma. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spunt, S.L.; Million, L.; Chi, Y.Y.; Anderson, J.; Tian, J.; Hibbitts, E.; Coffin, C.; McCarville, M.B.; Randall, R.L.; Parham, D.M.; et al. A risk-based treatment strategy for non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcomas in patients younger than 30 years (ARST0332): A Children’s Oncology Group prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedaghat, S.; Sedaghat, M.; Meschede, J.; Jansen, O.; Both, M. Diagnostic value of MRI for detecting recurrent soft-tissue sarcoma in a long-term analysis at a multidisciplinary sarcoma center. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitto, S.; Cuocolo, R.; Albano, D.; Morelli, F.; Pescatori, L.C.; Messina, C.; Imbriaco, M.; Sconfienza, L.M. CT and MRI radiomics of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas: A systematic review of reproducibility and validation strategies. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runkel, A.; Braig, D.; Bogner, B.; Schmid, A.; Lausch, U.; Boneberg, A.; Brugger, Z.; Eisenhardt, A.; Kiefer, J.; Pauli, T.; et al. Non-invasive monitoring of neoadjuvant radiation therapy response in soft tissue sarcomas by multiparametric MRI and quantification of circulating tumor DNA—A study protocol. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winfield, J.M.; Miah, A.B.; Strauss, D.; Thway, K.; Collins, D.J.; DeSouza, N.M.; Leach, M.O.; Morgan, V.A.; Giles, S.L.; Moskovic, E.; et al. Utility of multi-parametric quantitative magnetic resonance imaging for characterization and radiotherapy response assessment in soft-tissue sarcomas and correlation with histopathology. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrussell, I.; Winfield, J.M.; Orton, M.R.; Miah, A.B.; Zaidi, S.H.; Arthur, A.; Thway, K.; Strauss, D.C.; Collins, D.J.; Koh, D.-M.; et al. Radiomic Features From Diffusion-Weighted MRI of Retroperitoneal Soft-Tissue Sarcomas Are Repeatable and Exhibit Change After Radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 899180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunisada, T.; Nakata, E.; Fujiwara, T.; Hosono, A.; Takihira, S.; Kondo, H.; Ozaki, T. Soft-tissue sarcoma in adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappo, A.S.; Parham, D.M.; Rao, B.N.; Lobe, T.E. Soft Tissue Sarcomas in Children. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 1999, 16, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, G.; Das, K. Soft tissue sarcomas in children. Indian J. Pediatr. 2012, 79, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatziantoniou, C.; Schoot, R.A.; van Ewijk, R.; van Rijn, R.R.; ter Horst, S.A.J.; Merks, J.H.M.; Leemans, A.; De Luca, A. Methodological considerations on segmenting rhabdomyosarcoma with diffusion-weighted imaging—What can we do better? Insights Imaging 2023, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktas, E.; Arikan, S.M.; Ardıç, F.; Savran, B.; Arslan, A.; Toğral, G.; Karakaya, J.; Aribas, B.K. The importance of diffusion apparent diffusion coefficient values in the evaluation of soft tissue sarcomas after treatment. Pol. J. Radiol. 2021, 86, e291–e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ewijk, R.; Chatziantoniou, C.; Adams, M.; Bertolini, P.; Bisogno, G.; Bouhamama, A.; Caro-Dominguez, P.; Charon, V.; Coma, A.; Dandis, R.; et al. Quantitative diffusion-weighted MRI response assessment in rhabdomyosarcoma: An international retrospective study on behalf of the European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group Imaging Committee. Pediatr. Radiol. 2023, 53, 2539–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, G.; Fayter, D.; Lewis-Light, K.; McHugh, K.; Levine, D.; Phillips, B. Mind the gap: Extent of use of diffusion-weighted MRI in children with rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr. Radiol. 2015, 45, 778–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodyla, M.; Demircioglu, A.; Schaarschmidt, B.M.; Bertram, S.; Bruckmann, N.M.; Haferkamp, J.; Li, Y.; Bauer, S.; Podleska, L.; Rischpler, C.; et al. Evaluation of 18F-FDG PET and DWI Datasets for Predicting Therapy Response of Soft-Tissue Sarcomas Under Neoadjuvant Isolated Limb Perfusion. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Whole Area ADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) | Whole Area rADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) | Area with Lowest ADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) | Area with Lowest rADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.09 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.71 |

| 2 | 1.19 | 1.23 | 1.19 | 1.23 |

| 3 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.65 |

| 4 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.57 |

| 5 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| 6 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.54 | 0.58 |

| 7 | 1.58 | 1.08 | 1.58 | 1.08 |

| 8 | 0.77 | 1.13 | 0.77 | 0.94 |

| 9 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.47 |

| 10 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.43 |

| 11 | 1.23 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.74 |

| 12 | 1.34 | 1.07 | 1.34 | 1.07 |

| 13 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.87 |

| 14 | 2.53 | 1.82 | 2.10 | 1.51 |

| No. | Whole Area ADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) | ADC Change After Treatment (%) | Area with Lowest ADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) | ADC Change After Treatment (%) | Whole Area rADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) | rADC Change After Treatment (%) | Area with Lowest rADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) | rADC Change After Treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.38 | 127 | 1.38 | 153 | 1.1 | 128 | 0.91 | 128 |

| 2 | 1.94 | 163 | 1.94 | 163 | 1.58 | 128 | 1.29 | 105 |

| 3 | 1.96 | 255 | 1.96 | 255 | 2.41 | 371 | 3.74 | 575 |

| 4 | 2.06 | 286 | 2.06 | 290 | 1.83 | 316 | 3.15 | 553 |

| 5 | 1.16 | 105 | 1.16 | 130 | 1.1 | 106 | 1.05 | 124 |

| 6 | 1.09 | 116 | 1.09 | 202 | 1.06 | 105 | 1.05 | 181 |

| 7 | 1.54 | 97 | 1.54 | 97 | 1.66 | 154 | 1.53 | 142 |

| 8 | 0.68 | 88 | 0.68 | 88 | 0.62 | 55 | 0.55 | 59 |

| 9 | 1.27 | 208 | 1.27 | 208 | 0.91 | 194 | 1.93 | 411 |

| 10 | 1.37 | 232 | 1.37 | 254 | 1.19 | 253 | 1.79 | 416 |

| 11 | 1.17 | 95 | 1.17 | 126 | 1.02 | 104 | 1.04 | 141 |

| 12 | 2.57 | 192 | 2.57 | 192 | 1.92 | 179 | 1.79 | 167 |

| 13 | 1.33 | 122 | 1.33 | 134 | 1.18 | 123 | 1.24 | 143 |

| 14 | 3.34 | 132 | 3.34 | 159 | 2.27 | 125 | 1.25 | 83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Grzywińska, M.; Sobolewska, A.; Krawczyk, M.; Wierzchosławska, E.; Świętoń, D. MRI Diffusion Imaging as an Additional Biomarker for Monitoring Chemotherapy Efficacy in Tumors. Medicina 2026, 62, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010173

Grzywińska M, Sobolewska A, Krawczyk M, Wierzchosławska E, Świętoń D. MRI Diffusion Imaging as an Additional Biomarker for Monitoring Chemotherapy Efficacy in Tumors. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010173

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrzywińska, Małgorzata, Anna Sobolewska, Małgorzata Krawczyk, Ewa Wierzchosławska, and Dominik Świętoń. 2026. "MRI Diffusion Imaging as an Additional Biomarker for Monitoring Chemotherapy Efficacy in Tumors" Medicina 62, no. 1: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010173

APA StyleGrzywińska, M., Sobolewska, A., Krawczyk, M., Wierzchosławska, E., & Świętoń, D. (2026). MRI Diffusion Imaging as an Additional Biomarker for Monitoring Chemotherapy Efficacy in Tumors. Medicina, 62(1), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010173