Heart Failure in Poland: A 20-Year Epidemiological Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

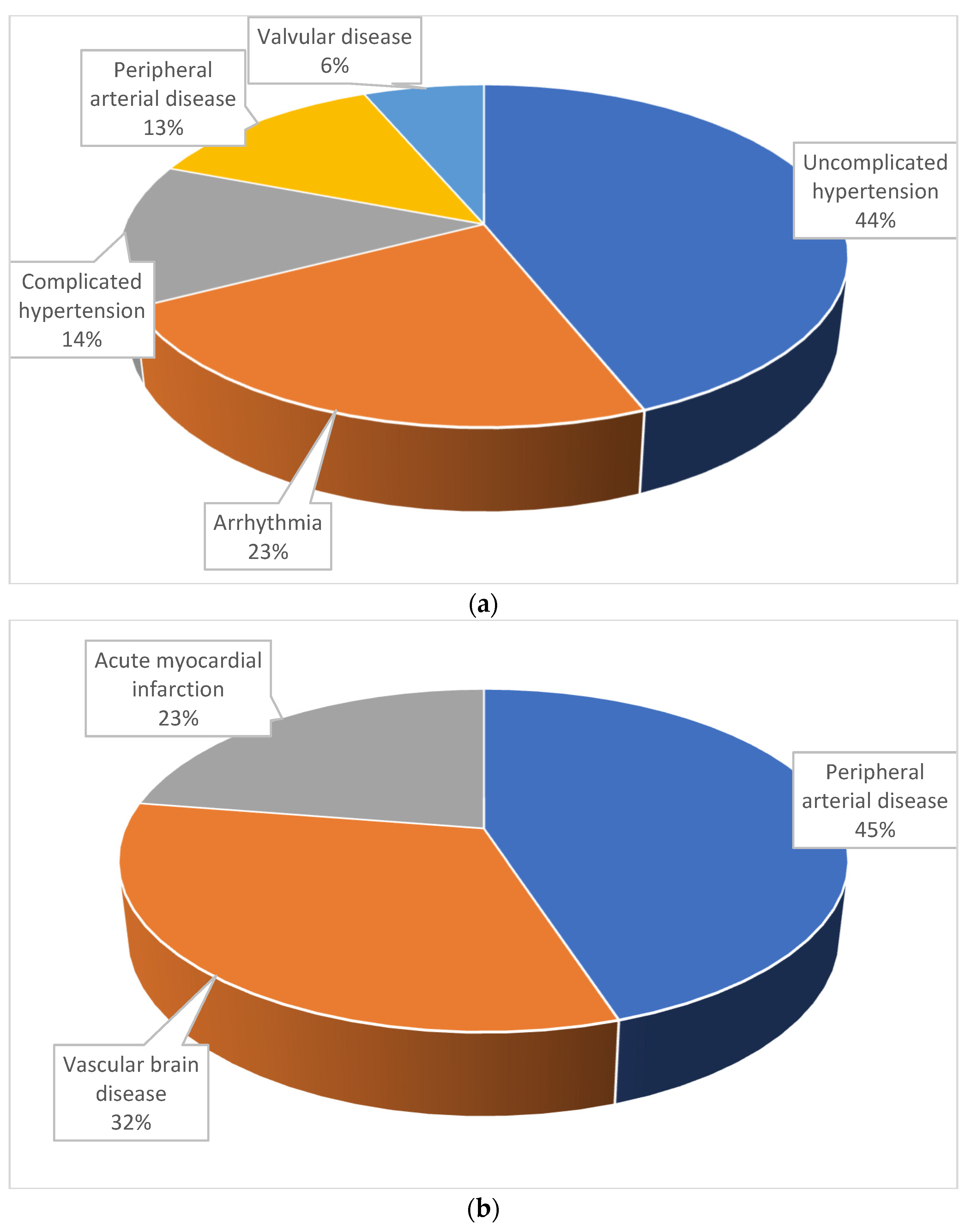

3.1. General Data

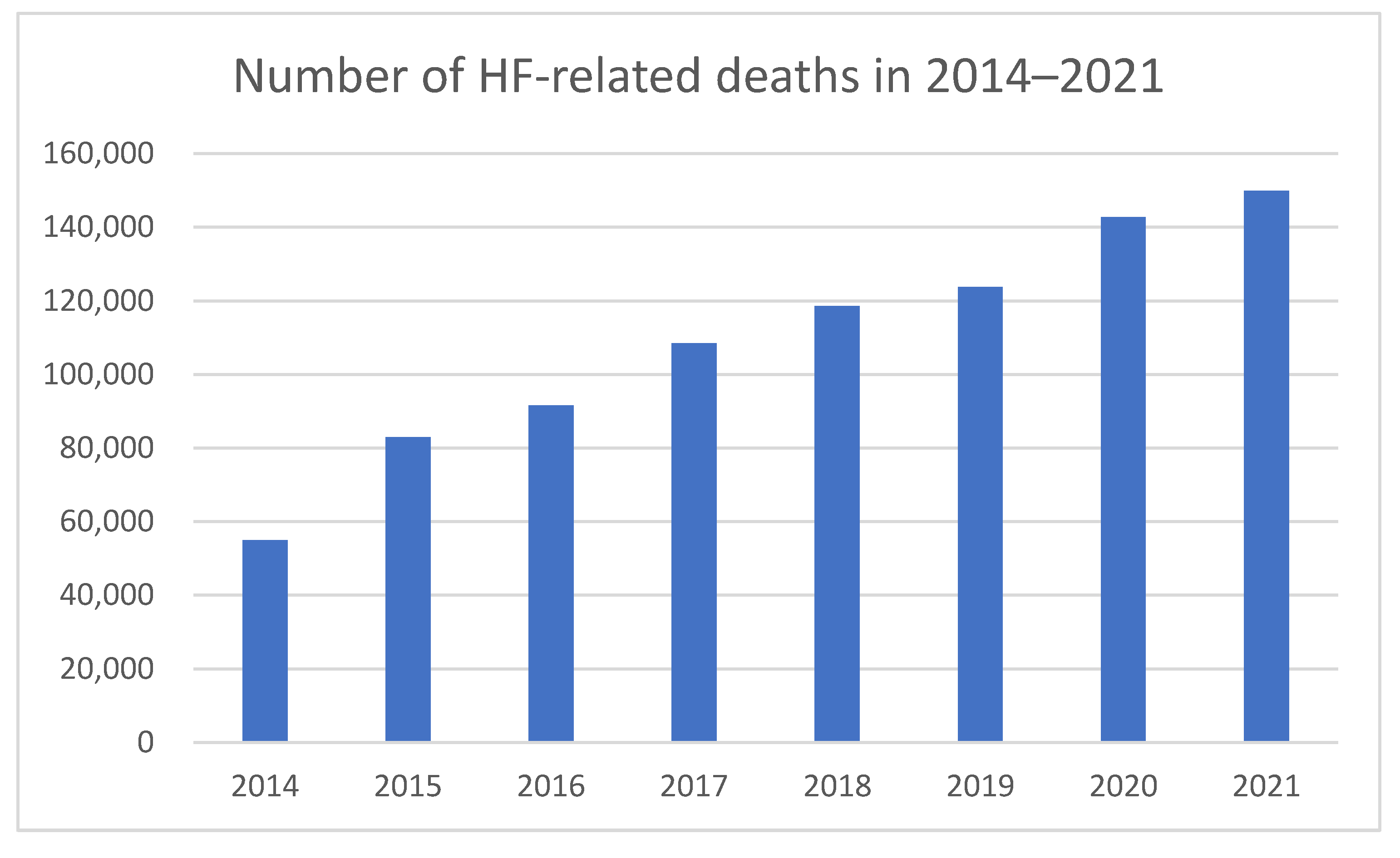

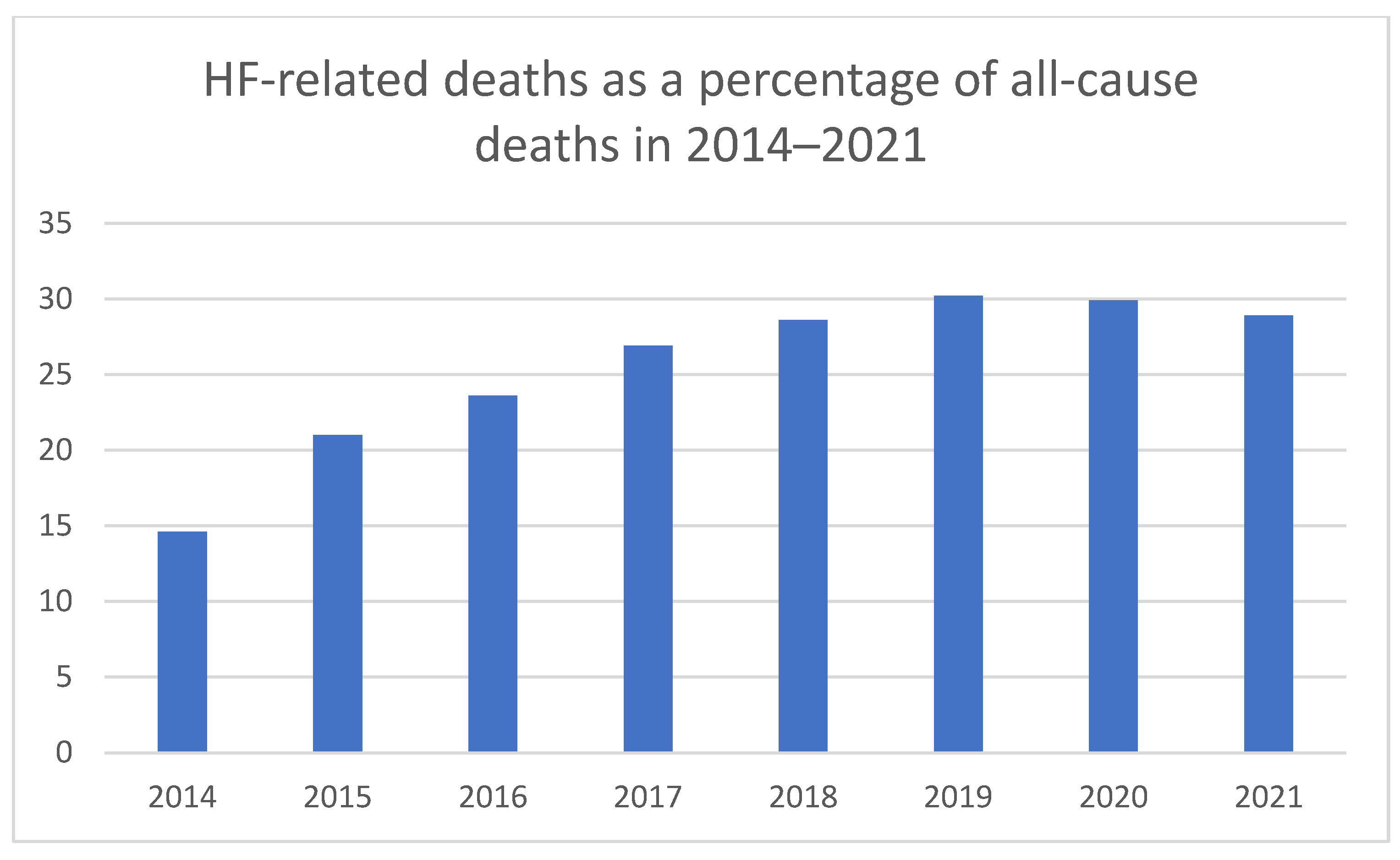

3.2. Mortality

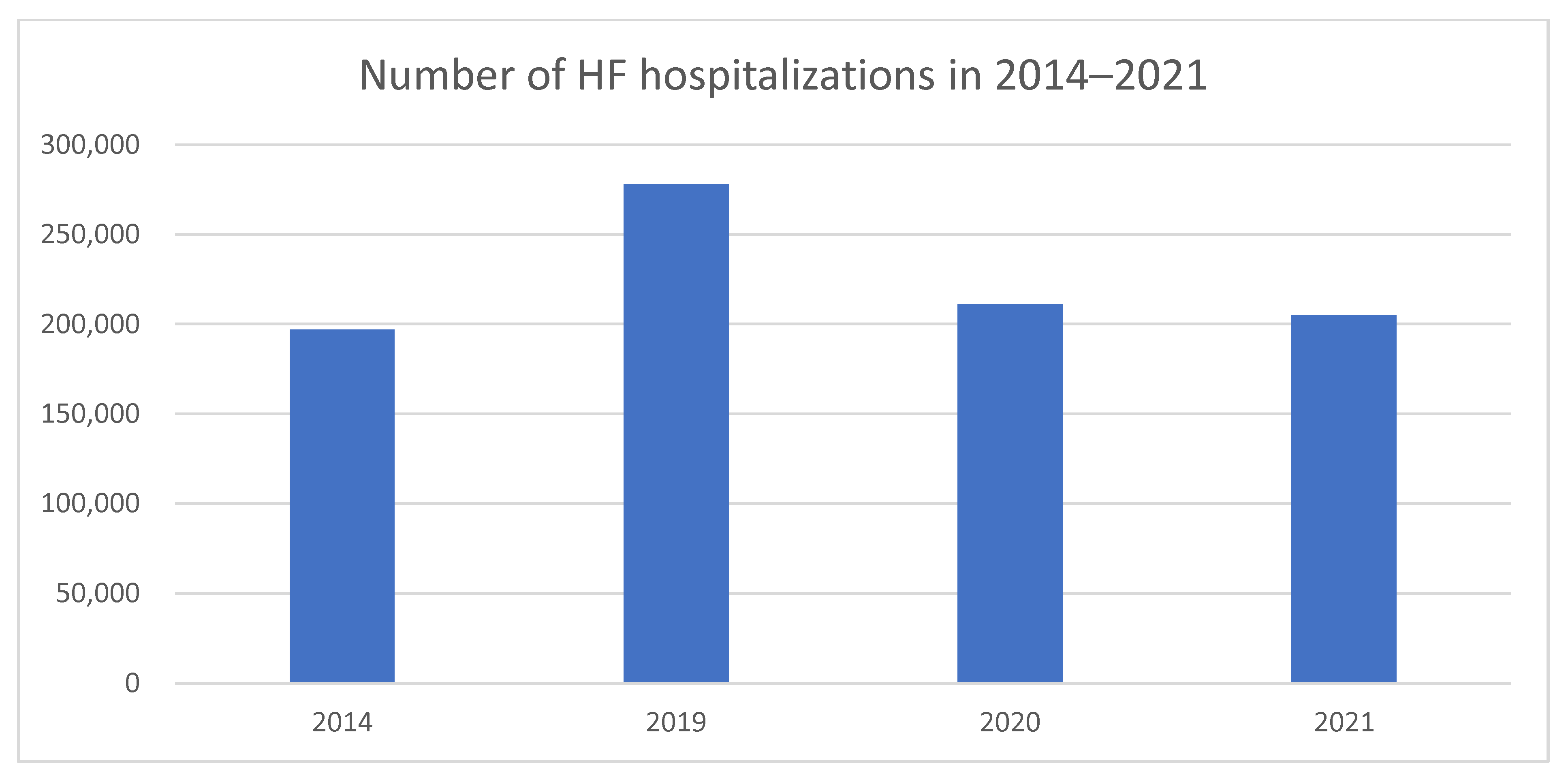

3.3. Hospitalizations

3.4. Rehabilitation and Palliative Care

3.5. HF Financial Burden

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Recommendations

4.2. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CR | cardiac rehabilitation |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| HF | Heart failure |

References

- CSO. Rocznik Demograficzny. 2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/areas-tematyczne/rocznik-statystyczne/rocznik-statystyczne/rocznik-demograficzny-2022,3,16.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- GUS. Sytuacja Demograficzna Polski do 2020 Roku. Deaths and mortality. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/sytuacja-demograficzna-polski-do-2020-roku-zgony-iumieralnosc,46,1.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Kałużna-Oleksy, M. (Ed.) Heart Failure in Poland. In Reality, Costs, Suggestions for Improving the Situation [Article in Polish]; Marfan Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://marfan.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Failure%CC%81c%CC%81RAPORT-A4-2021-NET.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.; Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, C.M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; Anker, S.D.; Atherton, J.; Böhm, M.; Butler, J.; et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2021, 23, 352–380. [Google Scholar]

- CSO. Mortality in 2021. Deaths by Cause—Preliminary Data. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/statystyka-przyczyn-zgonow/umieralnosc-w-2021-roku-zgonywedlug-przyczyn-dane-wstepne,10,3.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierczynski, J.; Gryglewicz, J.; Karczewicz, E.; Zalewska, H. Heart Failure—Analysis of Economic and Social Costs. Available online: https://izwoz.lazarski.pl/projekty-badawcze/raport-nt-niewydolnosci-serca (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Lelonek, M.; Pawlak, A.; Nessler, J.; Hryniewiecki, T.; Władysiuk, M. Heart Failure in Poland 2014–2021. Report. Available online: https://niewydolnosc-serca.pl/doc/ANS_raport_01.09_.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Aydın, S.Ş.; Aydemir, S.; Özmen, M.; Aksakal, E.; Saraç, I.; Aydınyılmaz, F.; Altınkaya, O.; Birdal, O.; Tanboğa, İ.H. The importance of Naples prognostic score in predicting long-term mortality in heart failure patients. Ann. Med. 2024, 57, 2442536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.F.; Lu, Y.; Katsouras, C.S.; Peng, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, M.; Liu, C.; Yao, H.; Lian, L.; Feng, X.; et al. Characteristics, outcomes and the necessity of continued guideline-directed medical therapy in patients with heart failure with improved ejection fraction. Ann. Med. 2024, 57, 2442535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heart Failure Health Problem Analysis (2014–2021). Web Application [Provided by the Ministry of Health]. Available online: https://analizy.mz.gov.pl:9443/WAS/app_NS/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Zhong, W.; Shu, J.; Abu Much, A.; Lotan, D.; Grupper, A.; Younis, A.; Dai, H. Burden of heart failure and underlying causes in 195 countries and territories from 1990 to 2017. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heart Failure in Poland. Realities, Costs, Suggestions for Improvement. Available online: https://marfan.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Non-heartfailure%CC%81c%CC%81--RAPORT-A4-2021-NET.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Ugarph-Morawski, A.; Wändell, P.; Benson, L.; Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H.; Dahlström, U.; Eriksson, B.; Edner, M. The association between anaemia, hospitalisation, and all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure managed in primary care: An analysis of the Swedish heart failure registry. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2025, 129, 105645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenzi, G.; Cosentino, N.; Imparato, L.; Trombara, F.; Leoni, O.; Bortolan, F.; Franchi, M.; Rurali, E.; Poggio, P.; Campodonico, J.; et al. Temporal trends (2003–2018) of in-hospital and 30-day mortality in patients hospitalised with acute heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 419, 132693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, C.J.; Gupta, A.; Hendren, N.S.; Farr, M.A.; Drazner, M.H.; Tang, W.W.; Grodin, J.L. Influence of Age on the Impact of a Natriuretic Peptide-Guided Treatment Strategy in Patients With Heart Failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2025, 234, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Ahmad, T.; Alexander, K.; Baker, W.L.; Bosak, K.; Breathett, K.; Carter, S.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. HF STATS 2024: Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics An Updated 2024 Report from the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card. Fail. 2025, 31, 66–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Allen, N.B.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Bansal, N.; Beaton, A.Z.; et al. 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 151, e41–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Załęska-Kocięcka, M.; Podwojcic, K.; Wojdyńska, Z.; Zakrzewski, M.; Celińska-Spodar, M.; Hryniewiecki, T.; Leszek, P. Heart failure epidemiology and outcomes in Poland from 2010 to 2021: A marked decline in HF hospitalization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kardiol. Pol. 2025, 83, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittipibul, V.; Vaduganathan, M.; Ikeaba, U.; Chiswell, K.; Butler, J.; DeVore, A.D.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Huang, J.C.; Kittleson, M.M.; Maddox, K.E.J.; et al. Cause-specific healthcare costs following hospitalization for heart failure and cost offset with SGLT2 inhibitor therapy. JACC Heart Fail. 2024, 12, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.S.; Xu, H.; Matsouaka, R.A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Devore, A.D.; Yancy, C.W.; Fonarow, G.C. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 2476–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rywik, T.M.; Wiśniewska, A.; Cegłowska, U.; Drohomirecka, A.; Topór-Mądry, R.; Łazarczyk, H.; Połaska, P.; Zieliński, T.; Doryńska, A. Heart failure with reduced, mildly reduced, and preserved ejection fraction: Outcomes and predictors of prognosis. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2023, 133, 16522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investigators G-CHF; Joseph, P.; Roy, A.; Lonn, E.; Störk, S.; Floras, J.; Mielniczuk, L.; Rouleau, J.-L.; Zhu, J.; Dzudie, A.; et al. Global variations in heart failure etiology, management, and outcomes. JAMA 2023, 329, 1650–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nessler, J.; Krawczyk, K.; Leszek, P.; Rubiś, P.; Rozentryt, P.; Gackowski, A.; Pawlak, A.; Straburzyńska-Migaj, E.; Jankowska, E.A.; Brzęk, A.; et al. Expert opinion of the Heart Failure Association of the Polish Society of Cardiology, the College of Family Physicians in Poland and the Polish Society of Family Medicine on the perioperative management of patients with heart failure. Kardiol. Pol. 2023, 81, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łyszczarz, B. Indirect costs and public finance consequences of heart failure in Poland, 2012-2015. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvish, M.; Shakoor, A.; Feyz, L.; Schaap, J.; van Mieghem, N.M.; A de Boer, R.; Brugts, J.J.; A van der Boon, R.M. Heart failure: Assessment of the global economic burden. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 3069–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostrom, J.; Searcy, R.; Walia, A.; Rzucidlo, J.; Banco, D.; Quien, M.; Sweeney, G.; Pierre, A.; Tang, Y.M.; Mola, A.P.; et al. Early termination of cardiac rehabilitation is more common with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction than with ischemic heart disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2020, 40, E26–E30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colella, T.J.; Gravely, S.; Marzolini, S.; Grace, S.L.; A Francis, J.; Oh, P.; Scott, L.B. Sex bias in referral of women to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation? A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, H.E.; Savage, P.D.; Ades, P.A. Cardiac rehabilitation participation in underserved populations. Minorities, low socioeconomic, and rural residents. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2011, 31, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | 2021 | 2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Number of Hospitalizations | Share (%) | Age (Years) | Number of Hospitalizations per 100,000 Inhabitants |

| 19–40 | 223 | 0.15 | 18–39 | 19 |

| 41–60 | 7100 | 4.89 | 40–49 | 92 |

| 61–80 | 74,431 | 51.27 | 50–59 | 342 |

| ≥81 | 63,428 | 43.69 | 60–69 | 1056 |

| 70–79 | 2873 | |||

| ≥81 | 7448 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bohdan, M.; Kowalczys, A.; Nessler, J.; Straburzyńska-Migaj, E.; Gruchała, M.; Lelonek, M. Heart Failure in Poland: A 20-Year Epidemiological Perspective. Medicina 2025, 61, 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081472

Bohdan M, Kowalczys A, Nessler J, Straburzyńska-Migaj E, Gruchała M, Lelonek M. Heart Failure in Poland: A 20-Year Epidemiological Perspective. Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081472

Chicago/Turabian StyleBohdan, Michał, Anna Kowalczys, Jadwiga Nessler, Ewa Straburzyńska-Migaj, Marcin Gruchała, and Małgorzata Lelonek. 2025. "Heart Failure in Poland: A 20-Year Epidemiological Perspective" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081472

APA StyleBohdan, M., Kowalczys, A., Nessler, J., Straburzyńska-Migaj, E., Gruchała, M., & Lelonek, M. (2025). Heart Failure in Poland: A 20-Year Epidemiological Perspective. Medicina, 61(8), 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081472