Organizational Wellbeing and Quality of Life in Healthcare Settings: Unexpected Similarities Across Different Roles?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

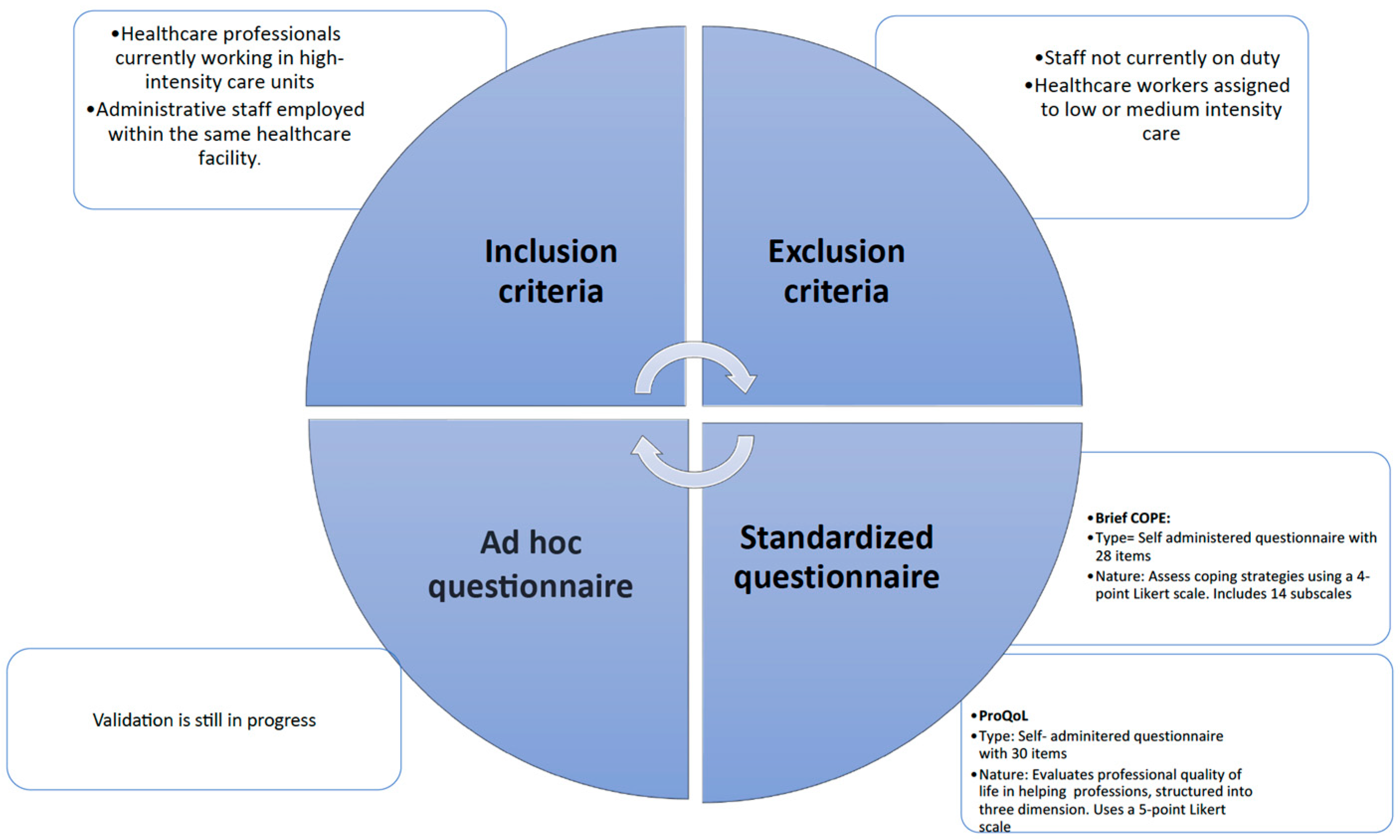

2.1. Stage 1: Enrollment

2.2. Stage 2: Administration

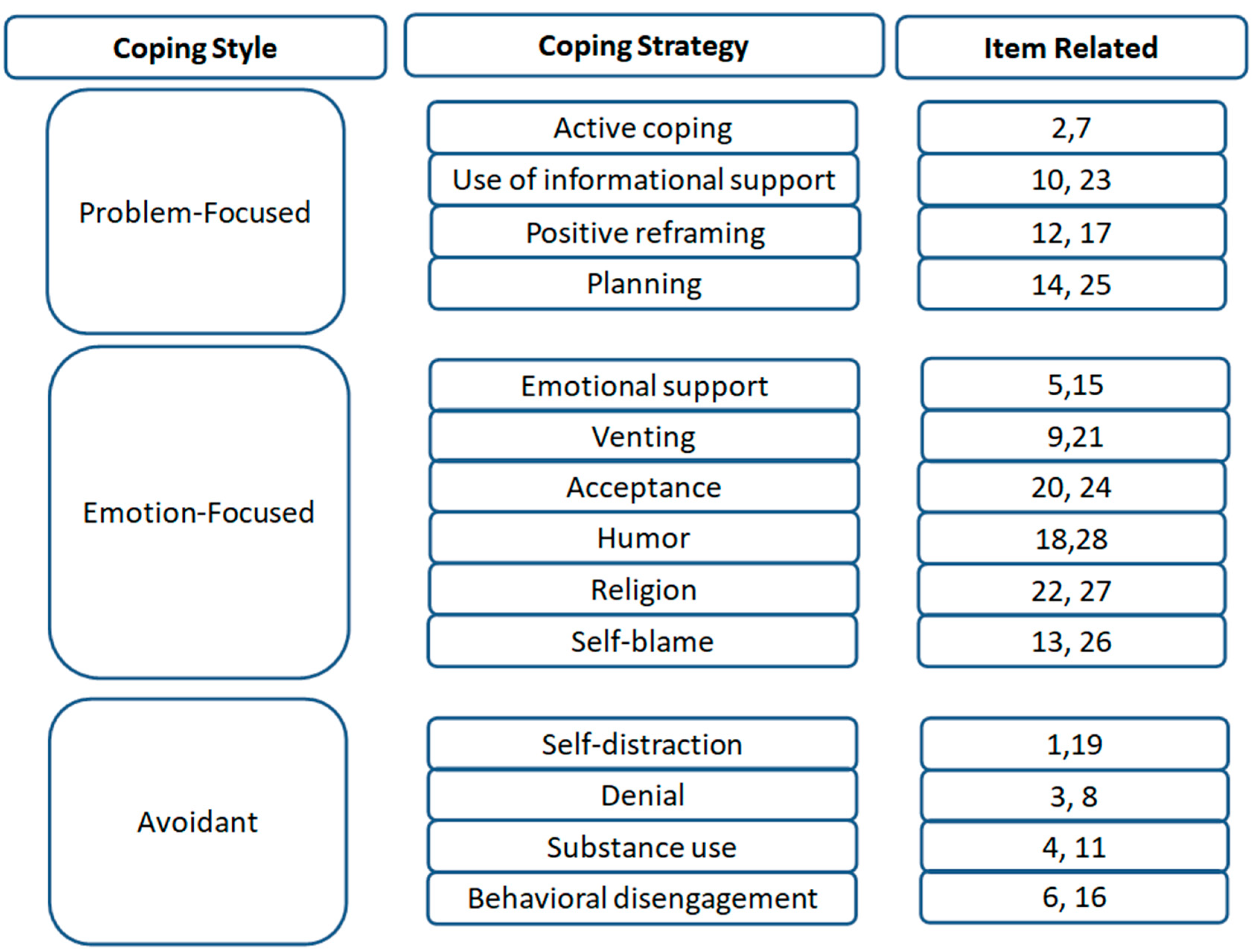

- The Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief COPE): is a self-report instrument developed by Charles S. Carver in 1997 [21], designed to evaluate the coping strategies individuals use in response to stress.

- Structure: A total of 28 items, grouped into 14 subscales (e.g., active coping, denial, substance use, and use of emotional support).

- Scoring: Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “I haven’t been doing this at all” to 4 = “I’ve been doing this a lot”). This tool does not yield a total score but the use of the individual subscales is interpreted independently.

- Interpretation: Scores for each subscale are calculated by summing the responses to the two items associated with that subscale; higher scores indicate greater use of that specific coping strategy.

- Reliability: Reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the subscales typically range from 0.50 to 0.90, depending on the population and subscale.

- Ad hoc Questionnaire differentiated by sectors to assess operational and structural challenges, aimed at promoting work well-being hindered by underestimated mechanisms.

- ProQoL [Professional Quality of Life]: ProQoL was developed by Beth Stamm in 2005 [17] to assess the professional quality of life among individuals in helping professions.

- Structure: A total of 30 items, divided into three subscales: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress.

- Scoring: Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Never” to 5 = “Very often”), with 10 items per subscale. Scores for each subscale are calculated by summing the responses and classifying them into three ranges, respectively, Low (≤22), Medium (23–41), or High (≥42).

- Interpretation: Each subscale score is calculated by summing relevant items. Higher Compassion Satisfaction scores indicate fulfillment in the caregiving role; higher Burnout or Secondary Traumatic Stress scores indicate emotional strain.

- Reliability: Internal consistency values reported in the literature include Cronbach’s alpha of approximately 0.88 (CS), 0.75 (BO), and 0.81 (STS).

2.3. Stage 3: Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Results

3.2. Analysis

3.3. Descriptive Analysis of ProQoL Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Perspectives

4.3. Policy Recommendations for Organizational Improvement

- Implement structured psychological support programs, particularly for staff in high-stress environments.

- Promote a culture of safety and organizational well-being, encouraging open communication and collaboration between clinical and administrative sectors.

- Provide targeted training on stress management and coping strategies, adapted to the specific roles and responsibilities of different staff categories.

- Regularly assess organizational climate and perceived workload, using validated tools to identify emerging risks and intervene proactively.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shdaifat, E.; Al-Shdayfat, N.; Al-Ansari, N. Professional Quality of Life, Work-Related Stress, and Job Satisfaction among Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. J. Environ. Public Health 2023, 2023, 2063212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. (WPA) 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; Andrade, S.M. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory; Scarecrow Education: Nagoro, Japan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Albendín-García, L.; Vargas-Pecino, C.; Ortega-Campos, E.M.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in Emergency Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdur, B.; Ergin, A.; Yüksel, A.; Türkçüer, İ.; Ayrık, C.; Boz, B. Assessment of the relation of violence and burnout among physicians working in the emergency departments in Turkey. Ulus. Travma Ve Acil Cerrahi Derg. = Turk. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. TJTES 2015, 21, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Cosentino, C.; Bettinaglio, G.C.; Giovanelli, F.; Prandi, C.; Pedrotti, P.; Preda, D.; D’Ercole, A.; Sarli, L.; Artioli, G. Nurse’s identity role during Covid-19. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2021, 92, e2021036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Palamenghi, L.; Graffigna, G. Stressors and Resources for Healthcare Professionals During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Lesson Learned From Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragioti, E.; Tsartsalis, D.; Mentis, M.; Mantzoukas, S.; Gouva, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of hospital staff: An umbrella review of 44 meta-analyses. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 131, 104272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søvold, L.E.; Naslund, J.A.; Kousoulis, A.A.; Saxena, S.; Qoronfleh, M.W.; Grobler, C.; Münter, L. Prioritizing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Healthcare Workers: An Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 679397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, O.; Sheehan, M.; Rau, R.I.; Sullivan, I.O.; McMahon, G.; Payne, A. Burnout on the frontline: The impact of COVID-19 on emergency department staff wellbeing. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 191, 2325–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F.; Neser, D.Y. Worker health is good for the economy: Union density and psychosocial safety climate as determinants of country differences in worker health and productivity in 31 European countries. Soc. Sci. Med. (1982) 2013, 92, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, M.R.; Searle, B.J.; Boyd, C.M.; Winefield, A.H.; Winefield, H.R. Hindrances are not threats: Advancing the multidimensionality of work stress. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.F.; Chang, Y.J. The Effects of Work Satisfaction and Work Flexibility on Burnout in Nurses. J. Nurs. Res. JNR 2022, 30, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhrabori, A.; Peyrovi, H.; Khankeh, H. The Main Features of Resilience in Healthcare Providers: A Scoping Review. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2022, 36, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guraya, S.Y.; Dias, J.M.; Eladl, M.A.; Rustom, A.M.R.; Alalawi, F.A.S.; Alhammadi, M.H.S.; Ahmed, Y.A.M.; Al Shamsi, A.A.O.T.; Bilalaga, S.J.; Nicholson, A.; et al. Unfolding insights about resilience and its coping strategies by medical academics and healthcare professionals at their workplaces: A thematic qualitative analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, B.H. The proQOL manual. Retrieved July 2005, 16, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Wen, S. Multidimensional perspectives on nurse burnout in China: A cross-sectional study of subgroups and predictors. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Barmawi, M.A.; Subih, M.; Salameh, O.; Sayyah Yousef Sayyah, N.; Shoqirat, N.; Abu Jebbeh, R.A.E. Coping strategies as moderating factors to compassion fatigue among critical care nurses. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, M.A.; DiazGranados, D.; Dietz, A.S.; Benishek, L.E.; Thompson, D.; Pronovost, P.J.; Weaver, S.J. Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listyowardojo, T.A.; Nap, R.E.; Johnson, A. Demographic differences between health care workers who did or did not respond to a safety and organizational culture survey. BMC Res Notes 2011, 4, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, L.C.; Oyesanya, T.O.; Adair, K.C.; Humphreys, J.C.; Silva, S.G.; Sexton, J.B. Stressors Among Healthcare Workers: A Summative Content Analysis. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2023, 10, 23333936231161127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet. Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bian, L.; Bai, X.; Kong, D.; Liu, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, N. The influence of job satisfaction, resilience and work engagement on turnover intention among village doctors in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hert, S. Burnout in Healthcare Workers: Prevalence, Impact and Preventative Strategies. Local Reg. Anesth. 2020, 13, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Fu, M.; Sun, K.; Liu, L.; Chen, P.; Li, L.; Niu, Y.; Wu, J. The mediating role of perceived social support on the relationship between lack of occupational coping self-efficacy and implicit absenteeism among intensive care unit nurses: A multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiroumpa, A.; Moisoglou, I.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Malliarou, M.; Sarafis, P.; Gallos, P.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Rizos, F.; Galanis, P. Resilience and Social Support Protect Nurses from Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2025, 13, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Gui, L. Compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction among emergency nurses: A path analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, I.; Santoro, P.E.; Benevene, P.; Borrelli, I.; Angelini, G.; Fiorilli, C.; Gualano, M.R.; Moscato, U. Buffering the Effects of Burnout on Healthcare Professionals’ Health-The Mediating Role of Compassionate Relationships at Work in the COVID Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaque, I.; Raza, A.Z.; Khan, A.A.; Jafri, Q.A. Medical Staff Work Burnout and Willingness to Work during COVID-19 Pandemic Situation in Pakistan. Hosp. Top. 2022, 100, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsandila-Kalakou, F.; Wiig, S.; Aase, K. Factors contributing to healthcare professionals’ adaptive capacity with hospital standardization: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamforth, K.; Rae, P.; Maben, J.; Lloyd, H.; Pearce, S. Perceptions of healthcare professionals’ psychological wellbeing at work and the link to patients’ experiences of care: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2023, 5, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, R.; Dollard, M.F.; Tuckey, M.R.; Dormann, C. Psychosocial safety climate as a lead indicator of workplace bullying and harassment, job resources, psychological health and employee engagement. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xiang, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Pan, J. Impact of clinical pathway implementation satisfaction, work engagement, and hospital-patient relationship on quality of care in Chinese nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2025, 72, e12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Healthcare Workers n (%) | Administrative Staff n (%) | Chi Square | p-Value (Cramer’s V) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 15 (42%) | 14 (52%) | 0.30 | 0.58 (V = 0.07) |

| Female | 21 (58%) | 13 (48%) | ||

| Age | ||||

| <30 years | 1 (3%) | 0 | 3.75 | 0.15 (V = 0.24) |

| 30–50 years | 17 (47%) | 19 (70%) | ||

| >50 years | 18 (50%) | 8 (30%) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/Cohabiting | 25 (69%) | 19 (70%) | 0 | 1 (V = 0) |

| Single/Widowed | 11 (31%) | 8 (30%) | ||

| Education level | ||||

| Junior college degree | 6 (17%) | 11 (41%) | 7.74 | 0.02 * (0.35) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 9 (25%) | 1 (4%) | ||

| Master’s degree and other specializations | 21 (58%) | 15 (56%) | ||

| Contract Position | ||||

| Fixed-term | 1 (2%) | 3 (11%) | 1.87 | 0.39 (0.17) |

| Permanent | 33 (92%) | 23 (85%) | ||

| Other | 2 (6%) | 1 (4%) |

| Item | Healthcare Workers (N = 36) | Administrative Staff (N = 27) | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Yes | % No | % Yes | % No | ||

| Have you had any work-related injuries? | 42 | 58 | 4 | 96 | p-value = 0.002 |

| Have you been sick frequently in the past year (greater than three episodes) for work-related physical or psychological reasons? | 11 | 89 | 7 | 93 | non-significant comparison |

| Do you have any unused vacation days left over from the previous year? | 89 | 11 | 78 | 22 | non-significant comparison |

| Has your request for vacation days resulted in organizational discomfort for the hospital company? | 64 | 36 | 26 | 74 | p-value = 0.006 |

| Have you ever thought about the possibility of changing jobs? | 50 | 50 | 56 | 44 | non-significant comparison |

| Have you ever been in situations where you were verbally and/or physically assaulted by users? | 53 | 47 | 30 | 70 | non-significant comparison |

| Do you feel that your skills have been valued by the hospital company? | 39 | 61 | 26 | 74 | non-significant comparison |

| Have you ever expressed any difficulties in the work environment to your superiors? | 78 | 22 | 74 | 26 | non-significant comparison |

| Have you made any improvement or solution proposals? | 93 | 7 | 75 | 25 | non-significant comparison |

| Have you received comprehensive information regarding any of your requests? | 33 | 67 | 33 | 67 | non-significant comparison |

| Item | Healthcare Workers Median (I–III Quartile) | Administrative Staff Median (I–III Quartile) | p-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I’ve been turning to work or other activities to take my mind off things | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.5) | 0.10 | r = 0.21 |

| 2. I’ve been concentrating my efforts on doing something about the situation I’m in | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 0.33 | r = 0.12 |

| 3. I’ve been saying to myself “this isn’t real.” | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.5) | 0.56 | r = 0.08 |

| 4. I’ve been using addictive behaviors or substances to make myself feel better | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.75 | r = 0.04 |

| 5. I’ve been getting emotional support from others | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.5–2.0) | 0.97 | r = 0.01 |

| 6. I’ve been giving up trying to deal with it | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.92 | r = 0.01 |

| 7. I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better | 3.0 (3.0–3.0) | 3.0 (2.0–3.0) | 0.47 | r = 0.09 |

| 8. I’ve been refusing to believe that it has happened | 1.0 (1.5–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.94 | r = 0.01 |

| 9. I’ve been saying things to let my unpleasant feelings escape | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.5) | 1.0 | r = 0.00 |

| 10. I’ve been getting help and advice from other people | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 0.96 | r = 0.01 |

| 11. I’ve been using alcohol or other drugs to help me get through it | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.85 | r = 0.03 |

| 12. I’ve been trying to see it in a different light, to make it seem more positive | 2.0(2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 0.90 | r = 0.02 |

| 13. I’ve been criticizing myself | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.97 | r = 0.01 |

| 14. I’ve been trying to come up with a strategy about what to do | 3.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 0.25 | r = 0.15 |

| 15. I’ve been getting comfort and understanding from someone. | 2.0 (1.75–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.66 | r = 0.06 |

| 16. I’ve been giving up the attempt to cope | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.50 | r = 0.09 |

| 17. I’ve been looking for something good in what is happening | 3.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 0.86 | r = 0.02 |

| 18. I’ve been making jokes about it. | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.32 | r = 0.13 |

| 19. I’ve been doing something to think about it less, such as going to movies, watching TV, reading, daydreaming, sleeping, or shopping | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.5–3.0) | 0.49 | r = 0.09 |

| 20. I’ve been accepting the reality of the fact that it has happened | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 0.85 | r = 0.03 |

| 21. I’ve been expressing my negative feelings | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.70 | r = 0.05 |

| 22. I’ve been trying to find comfort in my religion or spiritual beliefs | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.22 | r = 0.16 |

| 23. I’ve been trying to get advice or help from other people about what to do | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 0.89 | r = 0.02 |

| 24. I’ve been learning to live with it. | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 0.51 | r = 0.08 |

| 25. I’ve been thinking hard about what steps to take. | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 3.0 (2.0–3.0) | 1.0 | r = 0.001 |

| 26. I’ve been blaming myself for things that happened | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.86 | r = 0.02 |

| 27. I’ve been praying or meditating | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.14 | r = 0.19 |

| 28. I’ve been making fun of the situation | 2.0 (1.75–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.72 | r = 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corallo, F.; Pagano, M.; Anselmo, A.; Cappadona, I.; Cardile, D.; Bonanno, L.; D’Aleo, G.; Migliara, M.; Libro, S.; Anchesi, S.D.; et al. Organizational Wellbeing and Quality of Life in Healthcare Settings: Unexpected Similarities Across Different Roles? Medicina 2025, 61, 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081437

Corallo F, Pagano M, Anselmo A, Cappadona I, Cardile D, Bonanno L, D’Aleo G, Migliara M, Libro S, Anchesi SD, et al. Organizational Wellbeing and Quality of Life in Healthcare Settings: Unexpected Similarities Across Different Roles? Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081437

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorallo, Francesco, Maria Pagano, Anna Anselmo, Irene Cappadona, Davide Cardile, Lilla Bonanno, Giangaetano D’Aleo, Mersia Migliara, Stellario Libro, Smeralda Diandra Anchesi, and et al. 2025. "Organizational Wellbeing and Quality of Life in Healthcare Settings: Unexpected Similarities Across Different Roles?" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081437

APA StyleCorallo, F., Pagano, M., Anselmo, A., Cappadona, I., Cardile, D., Bonanno, L., D’Aleo, G., Migliara, M., Libro, S., Anchesi, S. D., De Luca, R., Libro, F., Longo Minnolo, A., & Crupi, M. F. (2025). Organizational Wellbeing and Quality of Life in Healthcare Settings: Unexpected Similarities Across Different Roles? Medicina, 61(8), 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081437