A Literature Review on Pain Management in Women During Medical Procedures: Gaps, Challenges, and Recommendations

Abstract

1. Background

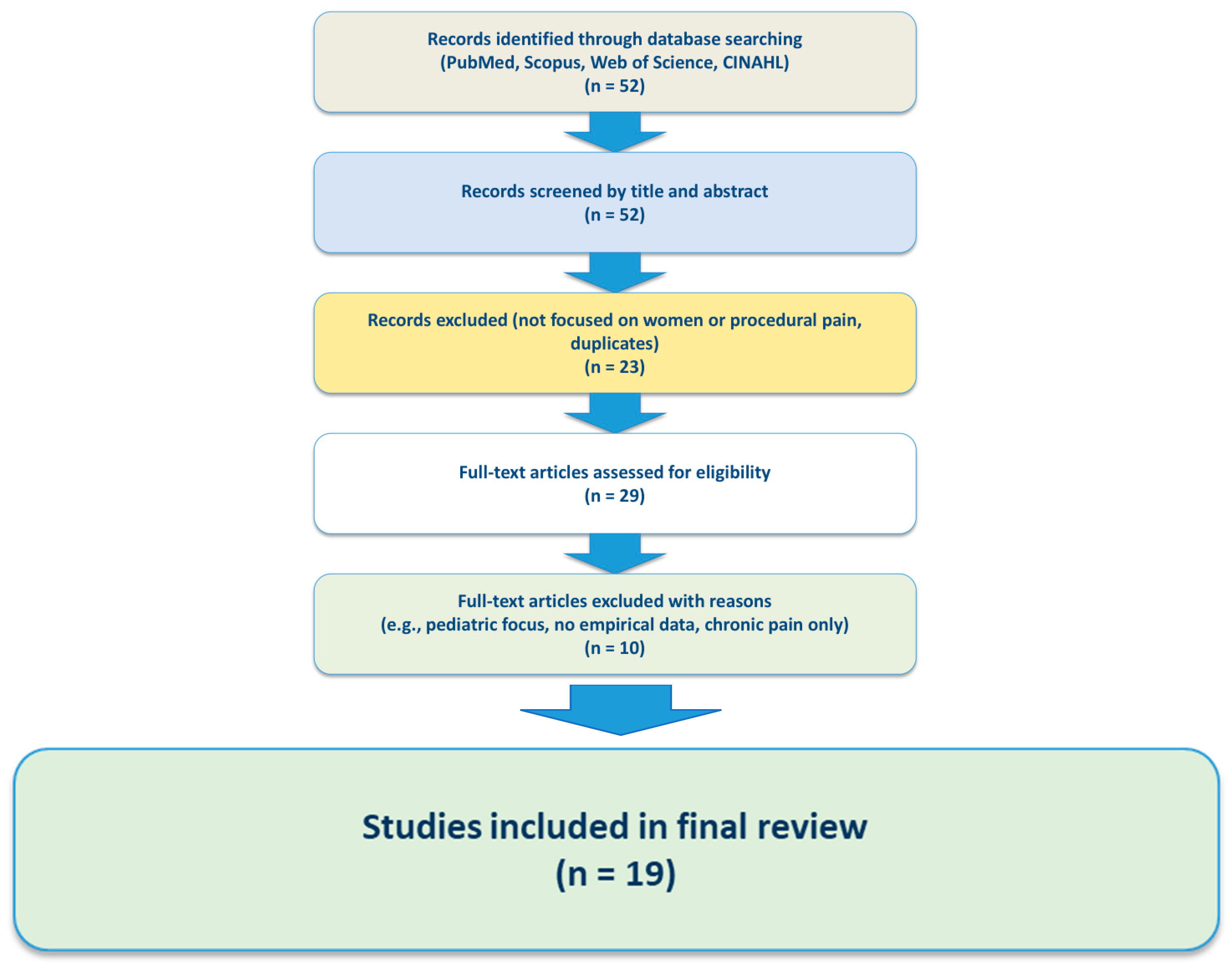

2. Methods

3. Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dahlhamer, J.; Lucas, J.; Zelaya, C.; Nahin, R.; Mackey, S.; DeBar, L.; Kerns, R.; Von Korff, M.; Porter, L.; Helmick, C. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, C.; De Luca, E.; D’Apice, C.; Artioli, G.; Sarli, L.; Bonacaro, A. Gender and sex bias in prevention and clinical treatment of women’s chronic pain: Hypotheses of a curriculum development. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1189126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, D.A.; Hobelmann, J.G.; Compton, P. Providing chronic pain management in the "Fifth Vital Sign" Era: Historical and treatment perspectives on a modern-day medical dilemma. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 173, S11–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieretti, S.; Di Giannuario, A.; Di Giovannandrea, R.; Marzoli, F.; Piccaro, G.; Minosi, P.; Aloisi, A.M. Gender differences in pain and its relief. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2016, 52, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillingim, R.B.; King, C.D.; Ribeiro-Dasilva, M.C.; Rahim-Williams, B.; Riley, J.L., III. Sex, gender, and pain: A review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J. Pain 2009, 10, 447–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.H.; Shofer, F.S.; Dean, A.J.; Hollander, J.E.; Baxt, W.G.; Robey, J.L.; Sease, K.L.; Mills, A.M. Gender disparity in analgesic treatment of emergency department patients with acute abdominal pain. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2008, 15, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, B.; Cui, J.; Kelly, A.M. The impact of patient sex on paramedic pain management in the prehospital setting. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2009, 27, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, K.; Taliaferro, L.A.; Brock, C.W.; Bazargan, S. Sex differences in the adequacy of pain management among patients referred to a multidisciplinary cancer pain clinic. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 36, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Losin, E.A.; Ashar, Y.K.; Koban, L.; Wager, T.D. Gender biases in estimation of others’ pain. J. Pain 2021, 22, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzikevits, M.; Choshen-Hillel, S.; Gileles-Hillel, A.; Shalvi, S. Sex bias in pain management decisions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401331121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, K.L. The influence of gender on the frequency of pain and sedative medication administered to postoperative patients. Sex Roles 1990, 23, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Lombana, W.; Gutiérrez Vidál, S.E. Pain and gender differences. A clinical approach. Colomb. J. Anestesiol. 2012, 40, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samulowitz, A.; Gremyr, I.; Eriksson, E.; Hensing, G. “Brave men” and “emotional women”: A theory-guided literature review on gender bias in health care and pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2018, 6358624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, S.; Coon, J.T.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Abbott, R.; Shaw, L.; Nunns, M.; Garside, R. Primary care clinicians’ perspectives on interacting with patients with gynaecological conditions: A systematic review. BJGP Open 2024, 8, BJGPO.2023.0133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samulowitz, A.; Hensing, G.; Haukenes, I.; Bergman, S.; Grimby-Ekman, A. General self-efficacy and social support in men and women with pain—Irregular sex patterns of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations in a general population sample. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, B.; Acevedo, M.; Appelman, Y.; Merz, C.N.B.; Chieffo, A.; Figtree, G.A.; Guerrero, M.; Kunadian, V.; Lam, C.S.; Maas, A.H. The Lancet Women and Cardiovascular Disease Commission: Reducing the global burden by 2030. Lancet 2021, 397, 2385–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzaccarini, G.; Alonso Pacheco, L.; Vitagliano, A.; Haimovich, S.; Chiantera, V.; Török, P.; Vitale, S.G.; Laganà, A.S.; Carugno, J. Pain management during office hysteroscopy: An evidence-based approach. Medicina 2022, 58, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, V.; Gil, G.F.; Arrieta, A.; Cagney, J.; DeGraw, E.; Herbert, M.E.; Khalil, M.; Mullany, E.C.; O’Connell, E.M.; Spencer, C.N.; et al. Differences across the lifespan between females and males in the top 20 causes of disease burden globally: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e282–e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellbeing of Women; Nurofen. The Gender Pain Gap Index Report 2022; United Kingdom. 2022. Available online: https://www.nurofen.co.uk/static/nurofen-gender-pain-gap-index-report-2024-8eede5529e884b5e496a1c02beea4210.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Ireland, L.D.; Allen, R.H. Pain management for gynecologic procedures in the office. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2016, 71, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Cruz, J.; Kather, A.; Nicolaus, K.; Rengsberger, M.; Mothes, A.R.; Schleussner, E.; Meissner, W.; Runnebaum, I.B. Acute postoperative pain in 23 procedures of gynecological surgery analyzed in a prospective open registry study on risk factors and consequences for the patient. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, E.; Hem-Lee-Forsyth, S.; Viechweg, N.D.; John, S.; Menor, S.P. Advancing pain management protocols for intrauterine device insertion: Integrating evidence-based strategies into clinical practice. Cureus 2024, 16, e63125. Available online: https://assets.cureus.com/uploads/review_article/pdf/265469/20240725-649483-xxq9jt.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Asgari, Z.; Razavi, M.; Hosseini, R.; Nataj, M.; Rezaeinejad, M.; Sepidarkish, M. Evaluation of paracervical block and IV sedation for pain management during hysteroscopic polypectomy: A randomized clinical trial. Pain Res. Manag. 2017, 2017, 5309408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, P.M.; Carnegy, A.; Smith, P.P.; Clark, T.J. Local anaesthesia for office hysteroscopy: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 252, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougher, E.; Zoorob, D.; Thomas, D.; Hagan, J.; Peacock, L. The effect of lidocaine gel on pain perception during diagnostic flexible cystoscopy in women: A randomized control trial. Urogynecology 2019, 25, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdarevic, M.; Striley, C.W.; Cottler, L.B. Sex differences in prescription opioid use. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimbish, L.A.; Simpson, J.R.; Gilbert, L.R.; Blackwood, A.; Grant, E.A. Examining Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Disparities in the Treatment of Pain and Injury Emergencies. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2022, 3, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Procedure/Treatment | Key Findings | Recommendations/ Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

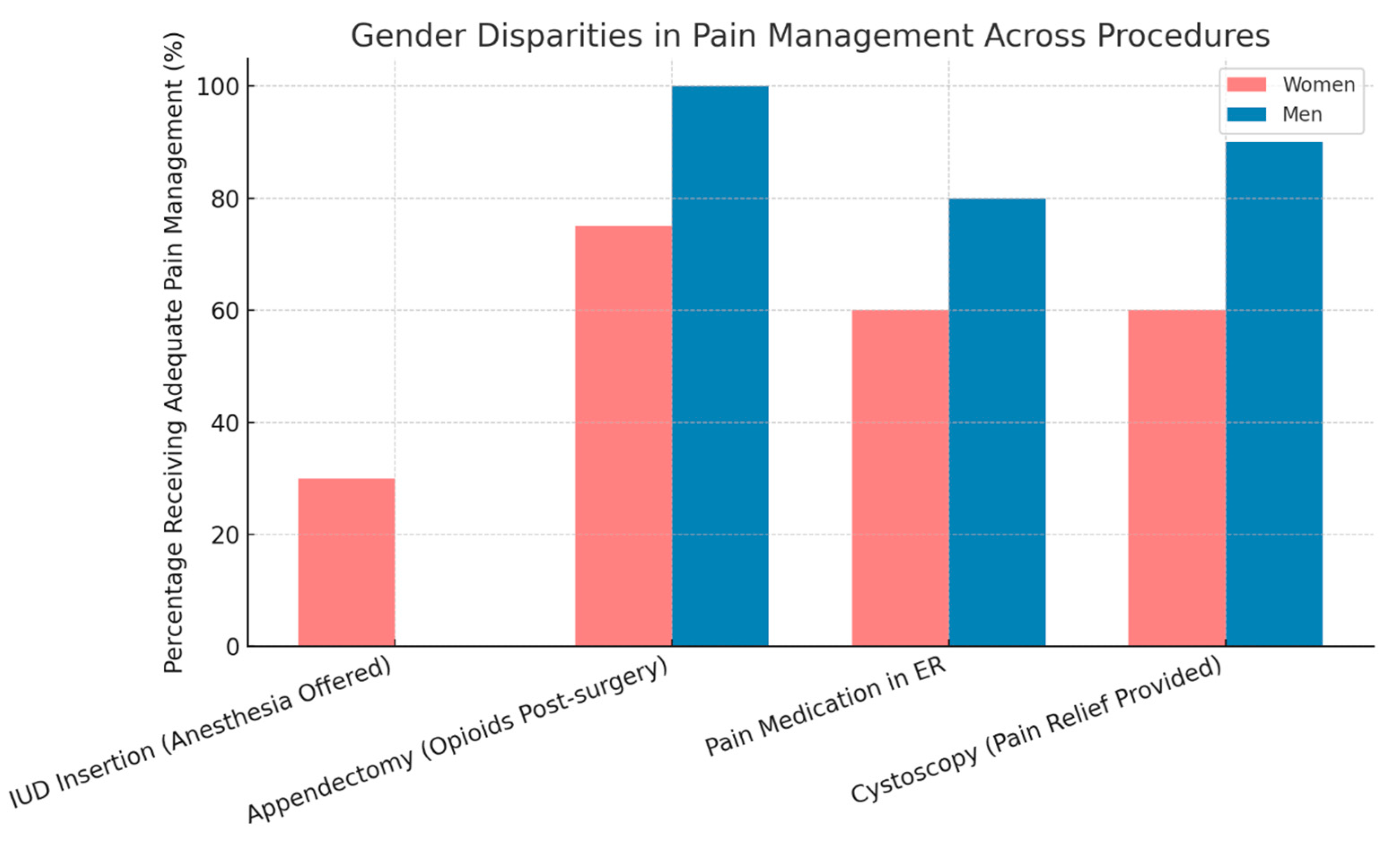

| Samulowitz et al. (2018) [13] | Pain management in ER and clinics | Women receive fewer pain medications than men despite similar pain levels. | Staff training, awareness of gender biases |

| Guzikevits et al. (2024) [10] | Emergency department (ED) pain management | Analysis of 21,851 ED patient records from two countries revealed a consistent sex bias: women were less likely to receive pain medications than men, even after adjusting for pain severity and other variables. Nurses were 10% less likely to record women’s pain scores, and women spent 30 min longer in the ED. Clinical vignettes confirmed bias in pain intensity judgments by nurses. | Raise awareness of implicit gender bias in clinical decision-making; implement policy changes to ensure equal pain treatment; provide training for healthcare providers |

| Estevez et al. (2024) [23] | IUD insertion | Only 30% of physicians offer anesthesia; 70% of women report moderate to severe pain. | Use of cervical anesthesia |

| Asgari et al. (2017) [24] | Cervical anesthesia | Anesthesia significantly reduces pain perception. | Systematic adoption of anesthesia protocols |

| De Silva PM et al. (2020) [25] | Diagnostic hysteroscopy without anesthesia | Pain levels 7–9 out of 10, especially among women with anxiety. | Holistic treatment, including anxiety management |

| Dougher et al. (2019) [26] | Cystoscopy | About 40% of clinics provide no pain relief beyond relaxation advice. | Improve pain management in procedures |

| Serdarevic et al. (2017) [27] | Prescription opioid use | Women are more likely than men to be prescribed opioids, use them chronically, and receive higher doses; women are also at increased risk of misuse. | Implement sex-specific guidelines for opioid prescribing; enhance monitoring and education to reduce misuse and improve pain outcomes |

| Wimblish et al. (2022) [28] | Prehospital pain management by EM | EMS providers administered opioids significantly less often to women and to Hispanic and American Indian/Alaska Native patients compared with White and male patients. | Address racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in EMS opioid administration through training and protocol standardization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grinberg, K.; Sela, Y. A Literature Review on Pain Management in Women During Medical Procedures: Gaps, Challenges, and Recommendations. Medicina 2025, 61, 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081352

Grinberg K, Sela Y. A Literature Review on Pain Management in Women During Medical Procedures: Gaps, Challenges, and Recommendations. Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081352

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrinberg, Keren, and Yael Sela. 2025. "A Literature Review on Pain Management in Women During Medical Procedures: Gaps, Challenges, and Recommendations" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081352

APA StyleGrinberg, K., & Sela, Y. (2025). A Literature Review on Pain Management in Women During Medical Procedures: Gaps, Challenges, and Recommendations. Medicina, 61(8), 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081352