Comparison of the Effectiveness and Complications of PAIR, Open Surgery, and Laparoscopic Surgery in the Treatment of Liver Hydatid Cysts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Open Surgery (OS)

2.2. Laparoscopic Surgery (LS)

2.3. PAIR

2.4. Statistical Analysis

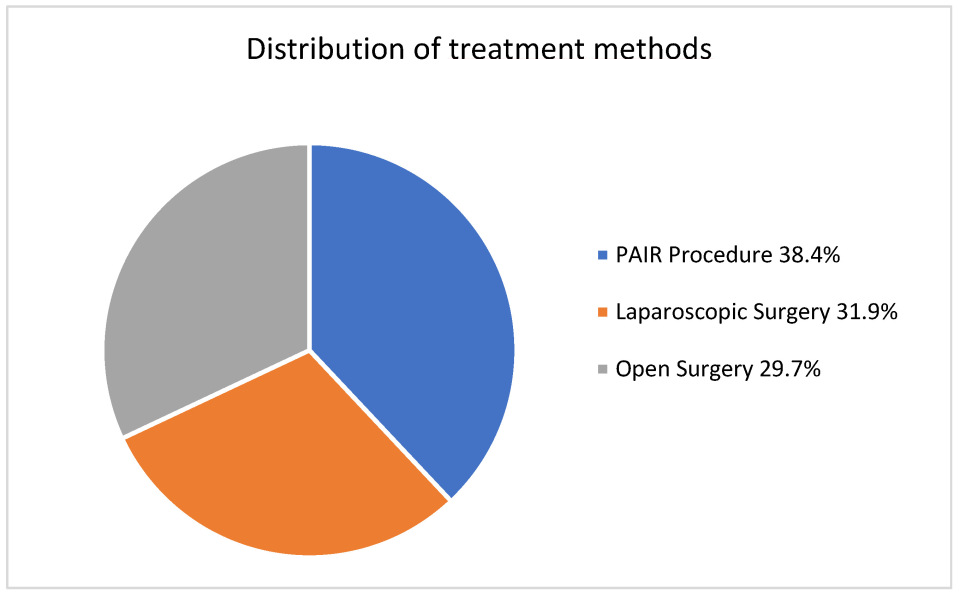

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christians, K.K.; Pitt, H.A. Hepatic abscess and cystic disease of the liver. In Maingot’s Abdominal Operations, 12th ed.; Zinner, M.J., Ashley, S.W., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 914–920. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, R.; Parilla, P. Abscesos y quistes hepáticos. Guías Clínicas A.E.C. Cirugía Hepática 2018, 6, 106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pascal, G.; Azoulay, D.; Belghiti, J. Hydatid disease of the liver. In Blumbgart’s Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1102–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Ramia Ángel, J.M.; Manuel Vázquez, A.; Gijón Román, C.; Latorre Fragua, R.; de la Plaza Llamas, R. Radical surgery in hepatic hydatidosis: Analysis of results in an endemic area. Rev. Esp. Enf. Dig. 2020, 112, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, I.; Tuerdi, M.; Zou, X.; Wu, Y.; Yasen, A.; Abihan, Y.; Xu, Q.; Balati, M.; Zhao, J.; Li, T.; et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for hepatic cystic echinococcosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 10, 16788–16797. [Google Scholar]

- Mihmanli, M.; Idiz, U.O.; Kaya, C.; Demir, U.; Bostanci, O.; Omeroglu, S.; Bozkurt, E. Current status of diagnosis and treatment of hepatic echinococcosis. World J. Hepatol. 2016, 8, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojkovic, M.; Rosenberger, K.; Kauczor, H.U.; Junghanss, T.; Hosch, W. Diagnosing and staging of cystic echinococcosis: How do CT and MRI perform in comparison to ultrasound? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharbi, H.A.; Hassine, W.; Brauner, M.W.; Dupuch, K. Ultrasound examination of the hydatic liver. Radiology 1981, 139, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Informal Working Group. International classification of ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis for application in clinical and field epidemiological settings. Acta Trop. 2003, 85, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Tirado, V.; Alonso-Sardón, M.; Lopez-Bernus, A.; Romero-Alegría, Á.; Burguillo, F.J.; Muro, A.; Carpio-Perez, A.; Bellido, J.L.M.; Pardo-Lleidas, J.; Cordero, M.; et al. Medical treatment of cystic echinococcosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkovic, M.; Zwahlen, M.; Teggi, A.; Vutova, K.; Cretu, C.M.; Virdone, R.; Nicolaidou, P.; Cobanoglu, N.; Junghanss, T. Treatment response of cystic echinococcosis to benzimidazoles: A systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvela-Suárez, L.; Velasco-Tirado, V.; Belhassen-Garcia, M.; Novo-Veleiro, I.; Pardo-Lledías, J.; Romero-Alegría, A.; del Villar, L.P.; Valverde-Merino, M.P.; Cordero-Sanchez, M. Safety of the combined use of praziquantel and albendazole in the treatment of human hydatid disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, R.; Khalid, R.; Abdelouahed, L.; Bennasser, F. Abdominal effusion revealing an exophytic hydatid cyst of the liver has developed under mesocolic. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 34, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, M.; Altıntas, Y. Current approaches in the surgical treatment of liver hydatid disease: Single center experience. BMC Surg. 2019, 19, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I.E.; Molina, R.F.X.; Segura, S.J.J.; González, A.X.; Morón, C.J.M. A review of the diagnosis and management of liver hydatid cyst. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2022, 114, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gavara, C.G.I.; López-Andújar, R.; Belda, I.T.; Ramia Ángel, J.M.; Moya, H.Á.; Orbis, C.F.; Pareja, I.E.; San Juan Rodriguez, F. Review of the treatment of liver hydatid cysts. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Javed, A.; Puri, S.; Jain, S.; Singh, S.; Agarwal, A.K. Hepatic hydatid: PAIR, drain or resect? J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2011, 15, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooghabi, A.J.; Bahar, M.M.; Asadi, M.; Nooghabi, M.J.; Jangjoo, A. Evaluation and comparison of the early outcomes of open and laparoscopic surgery of liver hydatid cyst. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2015, 25, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksungur, N.; Korkut, E.; Salih, K. Open and laparoscopic surgical treatment of cavity infection after percutaneous treatment for liver hydatid disease. Laparosc. Endosc. Surg. Sci. 2023, 30, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shera, T.A.; Choh, N.A.; Gojwari, T.A.; Shera, F.A.; Shaheen, F.A.; Wani, G.M.; Robbani, I.; Chowdri, N.A.; Shah, A.H. A comparison of imaging-guided double percutaneous aspiration injection and surgery in the treatment of cystic echinococcosis of liver. Br. J. Radiol. 2017, 90, 20160640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharie, F.; Valean, D.; Zaharie, R.; Popa, C.; Mois, E.; Schlanger, D.; Fetti, A.; Zdrehus, C.; Ciocan, A.; Al-Hajjar, N. Surgical management of hydatid cyst disease of the liver: An improvement from our previous experience? World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokouti, M.; Sadeghi, R.; Pashazadeh, S.; Abadi, S.E.H.; Sokouti, M.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Sokouti, B. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the treatment of liver hydatid cyst using meta-MUMS tool: Comparing PAIR and laparoscopic procedures. Arch. Med. Sci. 2019, 15, 284–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.; Osman, T.; El Barbary, M. Laparoscopic versus open surgical management of liver hydatid cyst: A retrospective study. Egypt. J. Surg. 2022, 41, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Efanov, M.; Kurbonov, K.; Alikhanov, R.; Azzizoda, Z.; Tsvirkun, V.; Elizarova, N.; Kazakov, I.; Vankovich, A.; Koroleva, A. Comparison of Immediate and Long-term Outcomes after Laparoscopic and Open Radical Surgery for Hydatid Liver Cysts. HPB 2021, 23, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, P.F.; Mufti, G.N.; Wani, S.; Sheikh, K.; Baba, A.A.; Bhat, N.A.; Hamid, R. Comparison of laparoscopic and open surgery in hepatic hydatid disease in children: Feasibility, efficacy and safety. J. Minim. Access Surg. 2022, 18, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektasoglu, H.K.; Hasbahceci, M.; Tasci, Y.; Aydogdu, I.; Malya, F.U.; Kunduz, E.; Dolay, K. Comparison of Laparoscopic and Conventional Cystotomy/Partial Cystectomy in Treatment of Liver Hydatidosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1212404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, V.; Thakur, S.U.; Mehta, S.; Dekhaiya, F.A. Comparative study of laparoscopic and open surgery in management of 50 cases of liver hydatid cyst. Int. Surg. J. 2020, 7, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijbas, S.A.R.; Al-Hakkak, S.; Alnajim, A. Laparoscopic or open treatment for liver hydatid cyst? A single-institution experience: A prospective randomized control trial. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 11, 4570–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Characteristics Findings | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| CE1 | Unilocular, anechoic cyst with double-line sign | Active |

| CE2 | Multiseptated “rosette-like” “honeycomb pattern” cyst | Active |

| CE3a | Cyst with detached membrane (water lily sign) | Transitional |

| CE3b | Daughter cysts in solid matrix | Transitional |

| CE4 | Heterogeneous cyst, no daughter vesicles | Inactive |

| CE5 | Solid matrix with calcified wall | Inactive |

| Overall (n = 383) | Treatment Method | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic (n = 122) | PAIR (n = 147) | Open (n = 114) | |||

| Age | 33.0 [18.0–79.0] | 34.0 [18.0–79.0] | 34.0 [18.0–73.0] | 32.0 [18.0–76.0] | 0.756 ** |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 270 (70.5) | 78 (63.9) | 114 (77.6) b | 78 (68.4) a,b | 0.043 * |

| Male | 113 (29.5) | 44 (36.1) | 33 (22.4) b | 36 (31.6) a, b | |

| Cyst Location | |||||

| Right | 277 (72.3) | 91 (74.6) a,b | 113 (76.9) b | 73 (64.0) | <0.001 * |

| Left | 61 (15.9) | 14 (11.5) a | 34 (23.1) b | 13 (11.4) a | |

| Both lobes | 45 (11.7) | 17 (13.9) a | 0 (0.0) b | 28 (24.6) c | |

| Number of Cysts | |||||

| Single | 268 (70.0) | 88 (72.1) | 104 (70.7) | 76 (66.7) | 0.636 * |

| Multiple | 115 (30.0) | 34 (27.9) | 43 (29.3) | 38 (33.3) | |

| Localization | |||||

| Peripheral | 295 (77.0) | 89 (73.0) | 112 (76.2) | 94 (82.5) | <0.001 * |

| Central | 69 (18.0) | 32 (26.2) a | 18 (12.2) b | 19 (16.7) a,b | |

| Both | 19 (5.0) | 1 (0.8) a | 17 (11.6) b | 1 (0.9) a | |

| Longest Diameter of the Cyst (mm) | 9.0 [3.0–23.0] | 9.0 [4.0–21.0] | 9.0 [3.0–19.0] | 9.5 [5.0–23.0] | 0.553 ** |

| WHO Stage | |||||

| Stage 1 | 242 (63.2) | 90 (73.8) | 110 (74.8) | 42 (36.8) b | <0.001 * |

| Stage 2 | 141 (36.8) | 32 (26.2) a | 37 (25.2) | 72 (63.2) b | |

| Biliary Fistula Detected During the Procedure | 116 (30.3) | 54 (44.3) a | 12 (8.2) b | 50 (43.9) | <0.001 * |

| Biliary Discharge from Drain After the Procedure | 229 (59.8) | 89 (73.0) | 40 (27.2) b | 100 (87.7) c | <0.001 * |

| Spontaneous Closure of Biliary Fistula | 182 (79.5) | 79 (88.8) a | 19 (47.5) b | 84 (84.0) a | <0.001 * |

| ERCP for Biliary Fistula | 47 (12.3) | 10 (8.2) | 21 (14.3) | 16 (14.0) | 0.251 * |

| Major Complication | 69 (18.0) | 26 (21.3) | 22 (15.0) | 21 (18.4) | 0.399 * |

| Periop Anaphylaxis | 16 (4.2) | 10 (8.2) a | 3 (2.0) b | 3 (2.6) a,b | 0.043 * |

| Cavity Infection | 26 (6.8) | 6 (4.9) | 12 (8.2) | 8 (7.0) | 0.570 * |

| Recollection | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0.295 * |

| Sign of Intraop Cyst Rupture | 8 (2.1) | 5 (4.1) a | 0 (0.0) b | 3 (2.6) a | 0.038 * |

| Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | 6.0 [1.0–57.0] | 5.0 [2.0–57.0] | 6.0 [1.0–50.0] | 6.0 [2.0–25.0] | 0.065 ** |

| Catheter Removal Duration (Days) | 6.0 [1.0–270.0] | 5.0 [1.0–48.0] | 7.0 [1.0–270.0] | 6.0 [2.0–35.0] | 0.093 ** |

| Recurrence | 22 (5.7) | 4 (3.3) a | 14 (9.5) b | 4 (3.5) a,b | 0.043 * |

| The first imaging modality used in patient follow-up | |||||

| CT | 236 (61.6) | 122 (100.0) a | 0 (0.0) b | 114 (100.0) a | <0.001 * |

| USG | 147 (38.4) | 0 (0.0) a | 147 (100.0) b | 0 (0.0) a | |

| Cyst Dimension During Follow-Up (Longest Diameter—mm) | 5.0 [2.0–17.0] | 6.0 [2.0–17.0] | 5.0 [2.0–12.0] | 5.0 [2.0–17.0] | 0.066 ** |

| Follow-Up Period (Month) | 12.0 [1.0–60.0] | 6.0 [1.0–48.0] | 12.0 [6.0–60.0] | 12.0 [1.0–60.0] | <0.001 ** |

| Mortality | |||||

| Surviving | 379 (99.0) | 121 (99.2) | 146 (99.3) | 112 (98.2) | 0.693 * |

| Ex | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Second Catheter Insertion Due to Bilioma | 17 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) a | 9 (6.1) b | 8 (7.0) b | 0.015 * |

| Outcome | Independent Variable | OR or B (95% CI) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biliary Fistula Formation | Treatment Modality (Open vs. PAIR) | OR: 19.5 (7.8–49.1) | <0.001 | Significantly higher risk in open surgery |

| Treatment Modality (Laparoscopic vs. PAIR) | OR: 1.08 (0.60–1.94) | 0.80 | Not significant | |

| Intraoperative Biliary Fistula | OR: 7.47 (3.26–17.15) | <0.001 | Strong independent risk factor | |

| Cyst Localization (Peripheral vs. Central) | OR: 0.14 (0.06–0.31) | <0.001 | Protective | |

| WHO Stage II vs. I | OR: 0.49 (0.23–1.04) | 0.06 | Trend, not significant | |

| Recurrence | Cyst Localization (Peripheral vs. Central) | OR: 0.15 (0.04–0.55) | 0.004 | Significantly lower recurrence in this localization |

| Treatment Modality | — | NS | No independent effect | |

| Other variables | — | NS | — | |

| Hospitalization Length | Cyst Localization (Peripheral vs. Central) | B: +1.84 (±0.60) | 0.002 | Increases length of stay |

| Intraoperative Biliary Fistula | B: −4.13 (±0.73) | <0.001 | Decreases length of stay | |

| Treatment Modality | — | NS | No independent effect |

| Recurrence Status | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 22) | No (n = 361) | ||

| Treatment Method | |||

| LS | 4 (18.2) a | 118 (32.7) | 0.043 * |

| PAIR | 14 (63.6) | 133 (36.8) b | |

| OS | 4 (18.2) a | 110 (30.5) a | |

| Localization | |||

| Peripheral | 13 (59.1) a | 282 (78.1) b | 0.013 * |

| Central | 5 (22.7) a | 64 (17.7) | |

| Both | 4 (18.2) a | 15 (4.2) b | |

| Spontaneous Closure of Biliary Fistula | 5 (33.3) | 177 (82.7) | <0.001 * |

| ERCP for Biliary Fistula | 10 (45.5) | 37 (10.2) | <0.001 * |

| Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | 8.0 [1.0–50.0] | 5.0 [1.0–57.0] | 0.033 ** |

| Catheter Removal Duration (Days) | 17.5 [1.0–100.0] | 6.0 [1.0–270.0] | 0.002 ** |

| The First Imaging Modality Used in Patient Follow-Up | |||

| CT | 8 (36.4) | 228 (63.2) | 0.022 * |

| USG | 14 (63.6) | 133 (36.8) | |

| Second Catheter Insertion due to Bilioma | 5 (22.7) | 12 (3.3) | 0.002 * |

| Biliary Fistula | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 116) | No (n = 267) | ||

| Treatment Method | |||

| LS | 54 (46.6) | 68 (25.5) b | <0.001 * |

| PAIR | 12 (10.3) a | 135 (50.6) b | |

| OS | 50 (43.1) | 64 (24.0) b | |

| Cyst Location | |||

| Right | 79 (68.1) a | 198 (74.2) | 0.001 * |

| Left | 13 (11.2) a | 48 (18.0) a | |

| Both lobes | 24 (20.7) | 21 (7.9) b | |

| Localization | |||

| Peripheral | 68 (58.6) | 227 (85.0) b | <0.001 * |

| Central | 43 (37.1) | 26 (9.7) b | |

| Both | 5 (4.3) a | 14 (5.2) a | |

| Longest Diameter (mm) | 10.0 [5.0–23.0] | 9.0 [3.0–20.0] | <0.001 ** |

| Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | 7.0 [2.0–57.0] | 5.0 [1.0–34.0] | <0.001 ** |

| Catheter Removal Duration (Days) | 10.0 [1.0–270.0] | 5.0 [1.0–60.0] | <0.001 ** |

| Cyst Dimension During Follow-Up (Longest Diameter—mm) | 6.0 [2.0–15.0] | 5.0 [2.0–17.0] | 0.011 ** |

| Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | Catheter Removal Duration (Days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | |

| Catheter Removal Duration (Days) | 0.721 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | 0.106 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.252 |

| Longest Diameter (mm) | 0.363 | <0.001 | 0.328 | <0.001 |

| Follow-Up Period (Months) | 0.108 | 0.034 | 0.083 | 0.103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berhuni, M.S.; Kaya, V.; Yönder, H.; Gerger, M.; Tahtabaşı, M.; Kaya, E.; Elkan, H.; Tatlı, F.; Uzunköy, A. Comparison of the Effectiveness and Complications of PAIR, Open Surgery, and Laparoscopic Surgery in the Treatment of Liver Hydatid Cysts. Medicina 2025, 61, 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081351

Berhuni MS, Kaya V, Yönder H, Gerger M, Tahtabaşı M, Kaya E, Elkan H, Tatlı F, Uzunköy A. Comparison of the Effectiveness and Complications of PAIR, Open Surgery, and Laparoscopic Surgery in the Treatment of Liver Hydatid Cysts. Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081351

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerhuni, Mehmet Sait, Veysel Kaya, Hüseyin Yönder, Mehmet Gerger, Mehmet Tahtabaşı, Eyüp Kaya, Hasan Elkan, Faik Tatlı, and Ali Uzunköy. 2025. "Comparison of the Effectiveness and Complications of PAIR, Open Surgery, and Laparoscopic Surgery in the Treatment of Liver Hydatid Cysts" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081351

APA StyleBerhuni, M. S., Kaya, V., Yönder, H., Gerger, M., Tahtabaşı, M., Kaya, E., Elkan, H., Tatlı, F., & Uzunköy, A. (2025). Comparison of the Effectiveness and Complications of PAIR, Open Surgery, and Laparoscopic Surgery in the Treatment of Liver Hydatid Cysts. Medicina, 61(8), 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081351