Structural and Psychometric Properties of Neck Pain Questionnaires Through Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Sources and Search

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

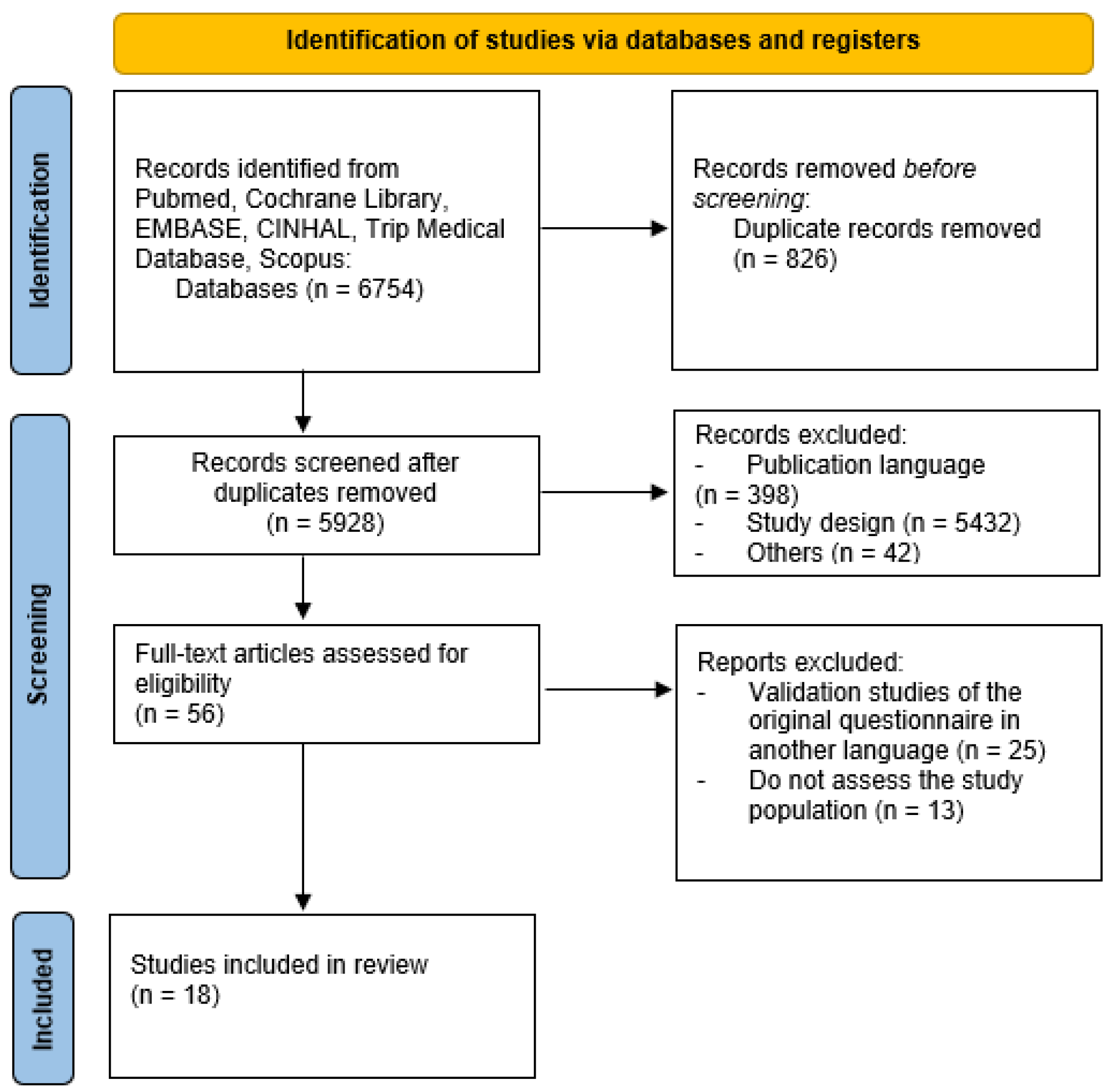

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Synthesis of Results and Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment of the Questionnaires Included

2.6.1. Test-Retest Reliability

Internal Consistency

2.6.2. Construction Validity

2.6.3. Factor Analysis

2.6.4. Sensitivity

2.6.5. Standard Error of Measurement

2.6.6. Minimal Detectable Change

2.6.7. Minimal Clinically Important Change

3. Results

3.1. Structural Variables

3.2. Psychometric Variables

3.3. COSMIN Checklist Analysis

| Questionnaire | Acronym | Population | Nº Items | Sub-Category | Time to Complete | Measurement (Best-Worst) | Versions | Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age | ||||||||

| 5-item version of the Neck Disability Index [21] | NDI-5 | 316 | 18–70 years | 5 | 5 Personal care; Concentration Work; Diving Recreation | - | 0–100 | 1 | - |

| Cervical Spine Outcomes Questionnaire [30] | CSOQ | 216 | 49.39 ± 10.15 years | 20 | 6 Neck pain severity Shoulder-arm pain severity Functional disability Phsycological distress Physical symptoms Health Care Utilization | - | 0–100 | 1 | - |

| Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale [37] | CNFDS | 162 | 38–56 | 15 | 0 | - | 0–30 | 9 | - |

| Dizziness Catastrophizing Scale [33] | DCS | 457 | 53.4 ± 15.4 years | 13 | 0 | - | 0–52 | 2 | - |

| Dizziness Handicap Inventory [24] | DHI | 63 | 49.4 ± 18.5 years | 25 | 3 Functional; Physical Emotional | - | 100–10 | 14 | - |

| Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire [20] | FABQ | N1 = 247 N2 = 220 N3 = 139 N4 = 338 | 44.64 ± 9.83 years 42.81 ± 9.99 years 43.06 ± 9.99 years 42.01 ± 9.51 years | 11 | 2 FABQPA: Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire Physical Activity; FABQW: Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire Work | 5 ± 3 min | 0–70 | 18 | - |

| Functional Rating Index [25] | FRI | N1 = 150 N2 = 25 | 41 ± 15.8 years 46 ± 19.2 years | 10 | 2 Function Pain | 78 s | 0–100 | 6 | - |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [26] | HADS | 100 | - | 14 | 2 Anxiety Depression | - | 0–21/each subscale | 21 | - |

| Neck Disability Index [27] | NDI | 52 | - | 10 | 10 Pain intensity Personal care Lifting Reading Headache Concentration Work Diving Sleeping Recreation | - | 0–100 | 31 | - |

| Neck OutcOme Score [28] | NOOS | 196 | 47.8 ± 13.7 years | 34 | 5 Mobility Symptoms Sleep Disturbance Everyday activity and pain Participating in everyday life | - | 0–100 | 4 | - |

| Neck Pain and Disability Scale [34] | NPDS | 100 | 44.26 ± 11.07 years | 20 | 0 | - | 0–100 | 13 | - |

| Patient Scar Assessment Questionnaire [29] | PSAQ | 667 | - | 28 | 4 Appearance Scar consciousness Satisfaction with appearance Satisfaction with symptoms | - | 112–0 | 7 | - |

| Patient-Specific Functional Scale 2.0 [35] | PSFS | 100 | 52.6 ± 14.5 years | 3 | 0 | - | 0–30 | 5 | - |

| The Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire [32] | NBQ | 102 | 45.4 ± 14.81 years | 7 | 0 | - | 0–70 | 10 | - |

| The Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire [19] | NPQ | 44 | 48 | 9 | 0 | - | 0–100 | 9 | - |

| The Profile Fitness Mapping neck Questionnaire [23] | ProFitMap-neck | N1 = 127 N2 = 83 N3 = 104 | 39.5 ± 10.5 years 42.9 ± 10.8 years 40.7 ± 9.9 years | 44 | 2 Symptom scale Functional limitation scale | - | 100–0 | 4 | - |

| Total Disability Index [22] | TDI | 252 | 55 years | 14 | 0 | - | 0–100 | 2 | - |

| Whiplash Disability Questionnaire [36] | WDQ | 66 | 41.55 ± 12.7 years | 13 | 0 | - | 0–130 | 3 | - |

| Questionnaire | Test-Retest Reliability (ICC) | Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s α) | Construction Validity | Factor Analysis | Sensitivity | SEM | MDC | MCID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-item version of the Neck Disability Index | 0.91 | - | r = 0.67 with NPRS r = 0.54 with TSK-11 r = 0.64 with PCS | - | - | 1.15 | 2.7 | - |

| Cervical Spine Outcomes Questionnaire | 0.75–0.86 | 0.80–0.94 | r = 0.36–0.69 with ODI r = −0.20–−0.65 with SF-36 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale | 0.92 | 0.90 | r = 0.83 with disability and pain scores r = 0.89 patient global assesment | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dizziness Catastrophizing Scale | 0.92 | 0.95 | PANAS negative r = 0.78 PANAS positive r = −0.40 | 61.6% | - | - | - | - |

| Dizziness Handicap Inventory | 0.97 | 0.89 | - | - | - | 6.23 | - | 18 |

| Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire | 0.81 | 0.90 | r = 0.33 with NRS; r = 0.53 with NPQ; r = −0.64 SF-36 (physical) r = −0.43 SF-36 (mental) | Factor 1: 40% Factor 2: 11.2% Factor 3: 10.5% Factor 4: 7.4% | - | - | - | - |

| Functional Rating Index | 0.99 | 0.92 | r = 0.71 | - | - | 2.1 | - | - |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | 0.54–0.79 | - | r = 0.70 for depression r = 0.74 for anxiety | - | - | - | - | - |

| Neck Disability Index | - | 0.80 | r = 0.89 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Neck OutcOme Score | 0.88–0.95 | 0.77–0.92 | r = 0.23–0.73 with SF-36 r = −0.54–−0.72 with NDI | - | - | 5.9–9.54 | 10–18 | - |

| Neck Pain and Disability Scale | - | 0.93 | - | Factor 1: 16.529% Factor 2: 18.527% Factor 3: 12.123% Factor 4: 19.424% | - | - | - | - |

| Patient Scar Assessment Questionnaire | 0.73–0.94 | 0.67–0.87 | Appearance: r = 0.25 to 0.71 Consciousness: r = 0.27 to 0.80 Satisfaction with Appearance: r = 0.59 to 0.88 Satisfaction with Symptoms: r = 0.52 to 0.91 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Patient-Specific Functional Scale | 0.95 | - | r = 0.60 with NDI r = 0.52 with GPE | - | - | 0.95−1.25 | 1.10 | 2.67 |

| The Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire | 0.65 | 0.87–0.92 | r = 0.50 with NDI r = 0.44 with CNFDS | - | - | - | - | - |

| The Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire | - | 0.62 | r = 0.84 | - | - | - | - | - |

| The Profile Fitness Mapping neck Questionnaire | 0.88–0.96 | 0.90 | r = 0.30–0.59 with SF-36 r ≥ 0.60 with NDI | - | - | 0.04 | 0.12 | - |

| Total Disability Index | 0.96 | 0.922 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Whiplash Disability Questionnaire | 0.89 | - | - | - | - | 7.72 | 21.41 | - |

| PROM | Content Validity | Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Cross-Cultural Validity | Reliability | Measurement Error | Criterion Validity | Hypothesis Testing | Responsiveness | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-item version of the Neck Disability Index [21] | - | - | - | - | • | • | • | - | - | 3 |

| Cervical Spine Outcomes Questionnaire [30] | - | - | • | - | • | - | • | - | - | 3 |

| Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale [37] | - | - | • | - | • | - | • | - | - | 3 |

| Dizziness Catastrophizing Scale [33] | - | • | • | - | • | - | • | • | • | 6 |

| Dizziness Handicap Inventory [24] | - | - | • | - | • | • | - | - | - | 3 |

| Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire [20] | - | • | • | • | • | - | • | • | • | 7 |

| Functional Rating Index [25] | - | - | • | - | • | • | • | • | • | 6 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [26] | - | - | - | - | • | - | • | - | - | 2 |

| Neck Disability Index [27] | - | - | • | - | • | - | • | • | • | 5 |

| Neck OutcOme Score [28] | - | - | • | - | • | • | • | • | • | 6 |

| Neck Pain and Disability Scale [34] | - | • | • | - | • | - | - | • | • | 5 |

| Patient Scar Assessment Questionnaire [29] | - | - | • | - | • | - | • | • | • | 5 |

| Patient-Specific Functional Scale 2.0 [35] | - | - | - | - | • | • | • | • | • | 5 |

| The Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire [32] | - | - | • | - | • | - | • | • | • | 5 |

| The Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire [19] | - | - | • | - | • | - | • | - | - | 3 |

| The Profile Fitness Mapping neck Questionnaire [23] | - | - | • | - | • | • | • | • | • | 6 |

| Total Disability Index [22] | - | - | • | - | • | - | - | • | • | 4 |

| Whiplash Disability Questionnaire [36] | - | - | - | - | • | • | - | - | - | 2 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Variables

4.2. Psychometric Variables

4.2.1. Reliability

4.2.2. Internal Consistency

4.2.3. Construct Validity

4.2.4. Factor Analysis

4.2.5. Other Psychometric Properties

4.2.6. Applicability of the Results

4.2.7. Limits on the Design of Validation Studies

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNFDS | Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale |

| COSMIN | COnsensus-based Standards for selecting health Measurement Instruments |

| CSOQ | Cervical Spine Outcomes Questionnaire |

| DALYS | Disability-adjusted life years |

| DCS | Dizziness Catastrophizing Scale |

| DHI | Dizziness Handicap Inventory |

| FABQ | Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire |

| FRI | Functional Rating Index |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| ICF | International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health |

| NBQ | Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire |

| NDI | Neck Disability Index |

| NOOS | Neck OutcOme Score |

| NDI-5 | 5-item version of the Neck Disability Index |

| NPDS | Neck Pain and Disability Scale |

| NPQ | Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire |

| MCID | Minimal Clinically Important Difference |

| MDC | Minimal Detectable Change |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| ProFitMap-neck | Profile Fitness Mapping neck Questionnaire |

| PROM | Patient-reported outcome measure |

| PSAQ | Patient Scar Assessment Questionnaire |

| PSFS | Patient-Specific Functional Scale 2.0 |

| SF-36 | Short Form-36 Health Survey |

| TDI | Total Disability Index |

| SEM | Standard Error of Measurement |

| WDQ | Whiplash Disability Questionnaire |

References

- Corp, N.; Mansell, G.; Stynes, S.; Wynne-Jones, G.; Morsø, L.; Hill, J.C.; van der Windt, D.A. Evidence-based treatment recommendations for neck and low back pain across Europe: A systematic review of guidelines. Eur. J. Pain 2021, 25, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanpied, P.R.; Gross, A.R.; Elliott, J.M.; Devaney, L.L.; Clewley, D.; Walton, D.M.; Sparks, C.; Robertson, E.K. Neck Pain: Revision 2017. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2017, 47, A1–A83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryndal, A.; Glowinski, S.; Hebel, K.; Grochulska, A. Back pain in the midwifery profession in northern Poland. Peer J. 2025, 13, e19079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsener, T.; Kerry, M.; Biller-Andorno, N. A COSMIN systematic review of generic patient-reported outcome measures in Switzerland. Qual. Life Res. 2025, 34, 1869–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozanhan, B.; Yildiz, M. Questionnaire translation and questionnaire validation are not the same. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2020, 45, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, M.; Shellenbarger, T. Mastering survey design and questionnaire development. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2020, 51, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 2001. Available online: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Churruca, K.; Pomare, C.; Ellis, L.A.; Long, J.C.; Henderson, S.B.; Murphy, L.E.D.; Leahy, C.J.; Braithwaite, J. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): A review of generic and condition-specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdelilld, J.C.; Walton, D.M.; Avery, S.; Blanchard, A.; Etruw, E.; McAlpine, C.; Goldsmith, C.H. Measurement properties of the neck disability index: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2009, 39, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltychev, M.; Pylkäs, K.; Karklins, A.; Juhola, J. Psychometric properties of neck disability index—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 5415–5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Med. Clínica 2011, 135, 507–511. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025775310001454 (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Knol, D.L.; Stratford, P.W.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 63, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Vet, H. Observer Reliability and Agreement. Wiley StatsRef Stat. Ref. 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420–428. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18839484 (accessed on 22 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Prinsen, C.A.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Methodology for Systematic Reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). COSMIN Manual for Systematic Reviews of PROM. 2018. Available online: https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-syst-review-for-PROMs-manual_version-1_feb-2018.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- de Yébenes Prous, M.J.G.; Rodríguez Salvanés, F.; Carmona Ortells, L. Validation of questionnaires. Reumatol. Clínica 2009, 5, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- de Vet, H.C.; Terwee, C.B.; Ostelo, R.W.; Beckerman, H.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M. Minimal changes in health status questionnaires: Distinction between minimally detectable change and minimally important change. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leak, A.M.; Frank, A.O. The northwick park neck pain questionnaire, devised to measure neck pain and disability. Rheumatology 1994, 33, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-C.; Chiu, T.T.; Lam, T.-H. Psychometric properties of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire in patients with neck pain. Clin. Rehabil. 2006, 20, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, D.M.; MacDermid, J.C. A brief 5-item version of the Neck Disability Index shows good psychometric properties. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.L.; Ayres, E.W.; Spiegel, M.A.; Day, L.M.; Hart, R.A.; Ames, C.P.; Burton, D.C.; Smith, J.S.; Shaffrey, C.I.; Schwab, F.J.; et al. Validation of the recently developed Total Disability Index: A single measure of disability in neck and back pain patients. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2020, 32, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, M.; Hamberg, J.; Heiden, M.; Barnekow-Bergkvist, M. The ProFitMap-neck—Reliability and validity of a questionnaire for measuring symptoms and functional limitations in neck pain. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, G.P.; Newman, C.W. The Development of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 1990, 116, 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feise, R.J.; Michael Menke, J. Functional rating index: A new valid and reliable instrument to measure the magnitude of clinical change in spinal conditions. Spine 2001, 26, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, H.; Mior, S. The Neck Disability Index: A study of reliability and validity. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 1991, 14, 409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, T.; Søgaard, K.; Davis, A.M.; Roos, E.M. Psychometric properties of the Neck OutcOme Score, Neck Disability Index, and Short Form–36 were evaluated in patients with neck pain. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 79, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durani, P.; McGrouther, D.A.; Ferguson, M.W. The patient scar assessment questionnaire: A reliable and valid patient-reported outcomes measure for linear scars. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 123, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenDebba, M.; Heller, J.; Ducker, T.B.; Eisinger, J.M. Cervical spine outcomes questionnaire: Its development and psychometric properties. Spine 2002, 27, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoMartire, R.; Äng, B.O.; Gerdle, B.; Vixner, L. Psychometric properties of Short Form-36 Health Survey, EuroQol 5-dimensions, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients with chronic pain. PAIN 2020, 161, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.E.; Humphreys, B. The Bournemouth Questionnaire: A short-form comprehensive outcome measure. II. Psychometric properties in neck pain patients. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2002, 25, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothier, D.D.; Shah, P.; Quilty, L.; Ozzoude, M.; Dillon, W.A.; Rutka, J.A.; Gerretsen, P. Association Between Catastrophizing and Dizziness-Related Disability Assessed with the Dizziness Catastrophizing Scale. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 144, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, A.H.; Goolkasian, P.; Baird, A.C.; Darden, B.V. Development of the Neck Pain and Disability Scale. Spine 1999, 24, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoomes, E.; Cleland, J.A.; Falla, D.; Bier, J.; de Graaf, M. Reliability, Measurement Error, Responsiveness, and Minimal Important Change of the Patient-Specific Functional Scale 2.0 for Patients with Nonspecific Neck Pain. Phys. Ther. J. Rehabil. 2023, 1, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupar, M.; Côté, P.; Beaton, D.E.; Boyle, E.; Cassidy, J.D. A Test-Retest Reliability Study of the Whiplash Disability Questionnaire in Patients with Acute Whiplash-Associated Disorders. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2015, 38, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Manniche, C.; Mosdal, C.; Hindsberger, C. The Copenhagen neck functional disability scale: A study of reliability and validity. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 1998, 21, 520–527. [Google Scholar]

- Thoomes-de Graaf, M.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Cleland, J.A. The content and construct validity of the modified patient specific functional scale (PSFS 2.0) in individuals with neck pain. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2019, 28, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Vargas, A.I. Clinical practice of Physiotherapy evidence based: Research strategy, critical reading and asistential imple-mentation. Cuest. Fisioter. 2008, 1, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.A.; Akindele, M.O.; Umar, A.M.; Lawal, I.U.; Mohammed, J.; Ibrahim, A.A. The Hausa Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire: Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric assessment in patients with non-specific neck pain. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 46, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.N.; Naz, S.; Kousar, A.; Shahzad, K. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Northwick park neck pain questionnaire to Urdu language. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticone, M.; Baiardi, P.; Nido, N.; Righini, C.; Tomba, A.; Giovanazzi, E. Development of the Italian version of the neck pain and disability scale, NPDS-I: Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity. Spine 2008, 33, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Richardson, J.K.; Braga, L.; Menezes, A.; Soler, X.; Kume, P.; Zaninelli, M.; Socolows, F.; Pietrobon, R. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Neck Disability Index and Neck Pain and Disability Scale. Spine 2006, 31, 1621–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.S.; Kang, K.J.; Jang, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Chang, S.J. Evaluating test-retest reliability in patient-reported outcome measures for older people: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 79, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terkawi, A.S.; Tsang, S.; AlKahtani, G.J.; Al-Mousa, S.H.; Al Musaed, S.; AlZoraigi, U.S.; Alasfar, E.M.; Doais, K.S.; Abdulrahman, A.; Altirkawi, K.A. Development and validation of Arabic version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017, 11, S11–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondie, Y.; Mehnert, A.; Hinz, A.; Frey, R. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) applied to Ethiopian cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Palanchoke, J.; Abbott, J.H. Cross-cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Nepali Translation of the Patient-Specific Functional Scale. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, C.; McCaskey, M.; Ettlin, T. German translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the whiplash disability ques-tionnaire. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piker, E.G.; Kaylie, D.M.; Garrison, D.; Tucci, D.L. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: Factor Structure, Internal Consistency and Convergent Validity in Patients with Dizziness. Audiol. Neurotol. 2015, 20, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, F.; Peña, E.; Alba, M.; Sánchez, R. Consistencia interna y validez de contenido del instrumento DELBI. Rev. Colomb. Cancerol. 2015, 19, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Xu, B.-P.; Tian, Z.-R.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.-J.; Cui, X.-J. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Neck Pain and Disability Scale: A methodological systematic review. Spine J. 2019, 19, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H.; Lauche, R.; Langhorst, J.; Dobos, G.J.; Michalsen, A. Validation of the German version of the neck disability index (NDI). BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2014, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, M.L. Análisis factorial: Una aplicación en el cuestionario de salud general de Goldberg, versión de 12 preguntas. Rev. Chil. Salud Pública 2010, 11, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansirinukor, W. Thai version of the functional rating index for patients with back and neck pain: Part 1 cross-cultural adap-tation, reliability and validity. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2015, 98, S97–S105. [Google Scholar]

- Skaik, Y. Understanding and using sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 56, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Chang, R.; Zhang, E. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability and validity tests of the Chinese version of the Profile Fitness Mapping neck questionnaire. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Bahrami, E.; Pourbakht, A.; Jalaie, S.; Daneshi, A. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the dizziness handicap inventory. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 769–775. [Google Scholar]

- Valancius, D.; Ulyte, A.; Masiliunas, R.; Paskoniene, A.; Uloziene, I.; Kaski, D.; Vaicekauskiene, L.; Lesinskas, E.; Jatuzis, D.; Ryliskiene, K. Validation and factor analysis of the lithuanian version of the dizziness handicap inventory. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2019, 15, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; In, J.; Lee, S. Standard deviation and standard error of the mean. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015, 68, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, F.M.; Abraira, V.; Royuela, A.; Corcoll, J.; Alegre, L.; Tomás, M.; Mir, M.A.; Cano, A.; Muriel, A.; Zamora, J.; et al. Minimum detectable and minimal clinically important changes for pain in patients with nonspecific neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2008, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellingerhout, J.M.; Verhagen, A.P.; Heymans, M.W.; Koes, B.W.; de Vet, H.C.; Terwee, C.B. Measurement properties of disease-specific questionnaires in patients with neck pain: A systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Schellingerhout, J.M.; Verhagen, A.P.; Koes, B.W.; de Vet, H.C. Methodological quality of studies on the measurement properties of neck pain and disability questionnaires: A systematic review. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2011, 34, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellingerhout, J.M.; Heymans, M.W.; Verhagen, A.P.; de Vet, H.C.; Koes, B.W.; Terwee, C.B. Measurement properties of translated versions of neck-specific questionnaires: A systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemeunier, N.; da Silva-Oolup, S.; Olesen, K.; Shearer, H.; Carroll, L.J.; Brady, O.; Côté, E.; Stern, P.; Tuff, T.; Suri-Chilana, M.; et al. Reliability and validity of self-reported questionnaires to measure pain and disability in adults with neck pain and its associated disorders: Part 3—A systematic review from the CADRE Collaboration. Eur. Spine J. 2019, 28, 1156–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.L.; Borges, B.M.; Rezende, I.L.; Carvalho, L.P.; Soares, L.P.S.; Dabes, R.A.I.; Carvalho, G.; Drummond, A.S.; Machado, G.C.; Ferreira, P.H. Are neck pain scales and questionnaires compatible with the international classification of functioning, disability and health? A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicciari, L.; Bonetti, F.; Di Foggia, D.; Monesi, M.; Vercelli, S. Patient-reported outcome measures for non-specific neck pain validated in the Italian-language: A systematic review. Arch. Physiother. 2016, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonzalez-Sanchez, M.; Reina-Ruiz, Á.J.; Molina-Torres, G.; Trzcińska, S.K.; Carrasco-Vega, E.; Lochmannová, A.; Galán-Mercant, A. Structural and Psychometric Properties of Neck Pain Questionnaires Through Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071254

Gonzalez-Sanchez M, Reina-Ruiz ÁJ, Molina-Torres G, Trzcińska SK, Carrasco-Vega E, Lochmannová A, Galán-Mercant A. Structural and Psychometric Properties of Neck Pain Questionnaires Through Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071254

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzalez-Sanchez, Manuel, Álvaro Jesús Reina-Ruiz, Guadalupe Molina-Torres, Sandra Kamila Trzcińska, Elio Carrasco-Vega, Alena Lochmannová, and Alejandro Galán-Mercant. 2025. "Structural and Psychometric Properties of Neck Pain Questionnaires Through Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071254

APA StyleGonzalez-Sanchez, M., Reina-Ruiz, Á. J., Molina-Torres, G., Trzcińska, S. K., Carrasco-Vega, E., Lochmannová, A., & Galán-Mercant, A. (2025). Structural and Psychometric Properties of Neck Pain Questionnaires Through Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review. Medicina, 61(7), 1254. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071254