Changes in Quality of Life, Depression, and Menopausal Symptoms After Surgical Menopause and the Efficacy of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Gynecological Cancer Survivors: A One-Year Prospective Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Background and Purpose

2.3. Questionnaires

2.4. Details of the Questionnaires

2.4.1. QOL and Menopausal Symptom Assessment by FACT-G and ESS-19

2.4.2. Assessment of Emotional Distress by CES-D

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

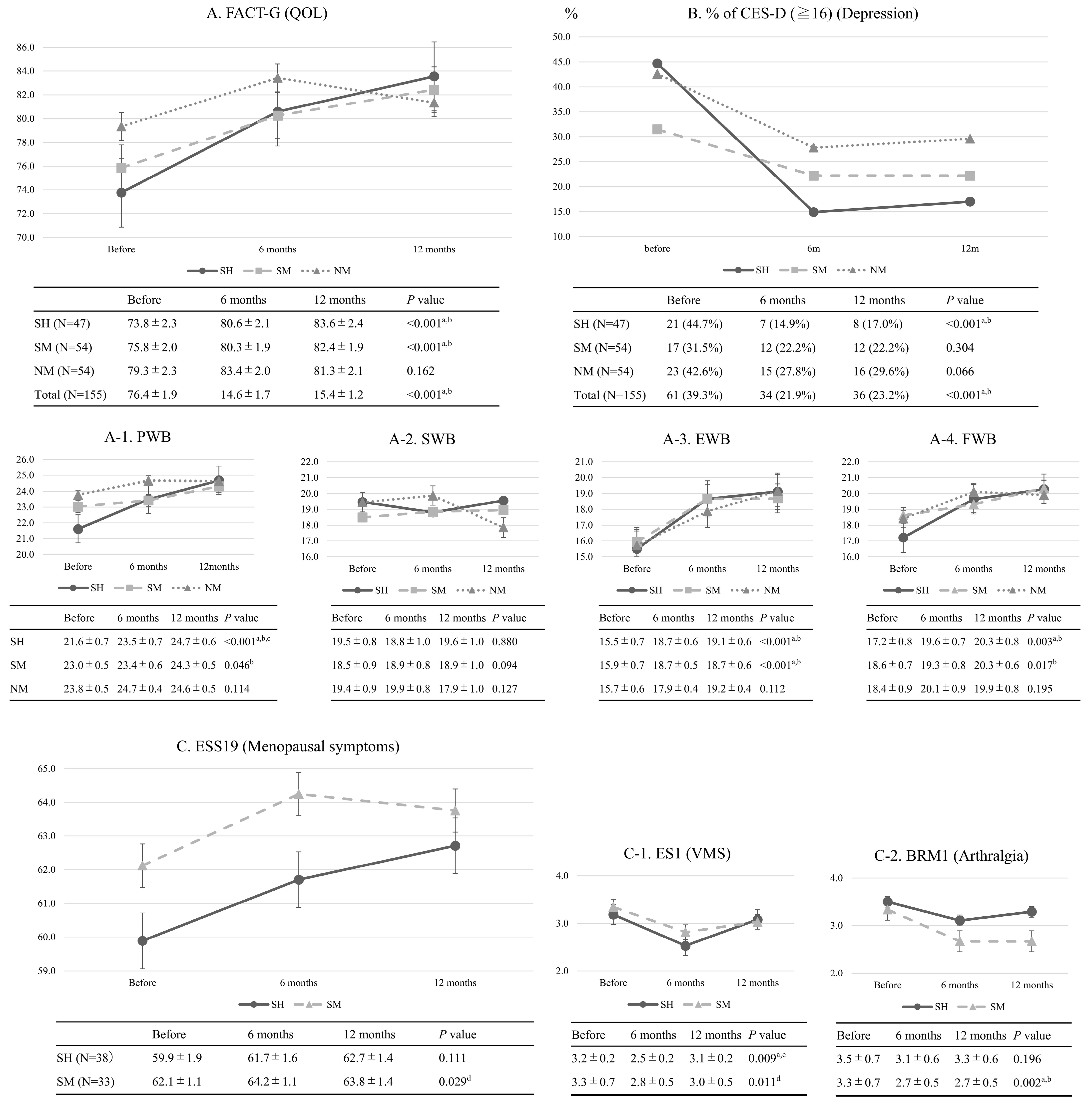

3.1. Changes in QOL, Emotional Distress, and Menopausal Symptoms

3.2. Examination of the Efficacy of HRT in GCSs After Surgical Menopause

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, H.; Ikeda, Y.; Kawana, K.; Nagase, S.; Yoshino, K.; Yamagami, W.; Tokunaga, H.; Kato, K.; Kimura, T.; Aoki, D.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on gynecological cancer incidence: A large cohort study in Japan. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 29, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.N.; Nguyen, V.T. Evaluating Clinical Features in Intracavitary Uterine Pathologies among Vietnamese Women Presenting with Peri-and Postmenopausal Bleeding: A Bicentric Observational Descriptive Analysis. J. Mid-Life Health 2022, 13, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.N.; Nguyen, V.T. Additional value of Doppler ultrasound to B-mode ultrasound in assessing for uterine intracavitary pathologies among perimenopausal and postmenopausal bleeding women: A multicentre prospective observational study in Vietnam. J. Ultrasound 2023, 26, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoupe, D.; Parker, W.H.; Broder, M.S.; Liu, Z.; Farquhar, C.; Berek, J.S. Elective oophorectomy for benign gynecological disorders. Menopause 2007, 14, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madalinska, J.B.; Hollenstein, J.; Bleiker, E.; van Beurden, M.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Massuger, L.F.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Mourits, M.J.; Verheijen, R.H.; van Dorst, E.B.; et al. Quality-of-life effects of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy versus gynecologic screening among women at increased risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6890–6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; Celik, C.; Görkemli, H.; Kiyici, A.; Kaya, B. Compared effects of surgical and natural menopause on climacteric symptoms, osteoporosis, and metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2009, 106, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocca, W.A.; Grossardt, B.R.; Geda, Y.E.; Gostout, B.S.; Bower, J.H.; Maraganore, D.M.; de Andrade, M.; Melton, L.J., 3rd. Long-term risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause 2018, 25, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.J.; Shin, A.; Kang, D. Hormone-related factors and post-menopausal onset depression: Results from KNHANES (2010–2012). J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianci, S.; Tarascio, M.; Arcieri, M.; La Verde, M.; Martinelli, C.; Capozzi, V.A.; Palmara, V.; Gulino, F.; Gueli Alletti, S.; Caruso, G.; et al. Post Treatment Sexual Function and Quality of Life of Patients Affected by Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C.S.; Leite, I.C.; Andrade, A.P.; de Souza Sergio Ferreira, A.; Carvalho, S.M.; Guerra, M.R. Sexual function of women surviving cervical cancer. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 293, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utian, W.H.; Woods, N.F. Impact of hormone therapy on quality of life after menopause. Menopause 2013, 20, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stute, P.; Spyropoulou, A.; Karageorgiou, V.; Cano, A.; Bitzer, J.; Ceausu, I.; Chedraui, P.; Durmusoglu, F.; Erkkola, R.; Goulis, D.G.; et al. Management of depressive symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women: EMAS position statement. Maturitas 2020, 131, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, M.; Angioli, R.; Coleman, R.L.; Glasspool, R.; Plotti, F.; Simoncini, T.; Terranova, C. European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS) and International Gynecologic Cancer Society (IGCS) position statement on managing the menopause after gynecological cancer: Focus on menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis. Maturitas 2020, 134, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Ito, K.; Takamatsu, K.; Takehara, K.; Nakanishi, T.; Harano, K.; Watari, H.; Susumu, N.; Aoki, D.; Saito, T. How do Japanese gynecologists view hormone replacement therapy for survivors of endometrial cancer? Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (JGOG) survey. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 20, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, K.; Kitawaki, J. Annual report of the Women’s Health Care Committee, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2017. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2018, 44, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, R.R.; Bundy, B.N.; Spirtos, N.M.; Bell, J.; Mannel, R.S. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S.; Gray, G.; Sarafian, B.; Linn, E.; Bonomi, A.; Silberman, M.; Yellen, S.B.; Winicour, P.; Brannon, J.; et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993, 11, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallowfield, L.J.; Leaity, S.K.; Howell, A.; Benson, S.; Cella, D. Assessment of quality of life in women undergoing hormonal therapy for breast cancer: Validation of an endocrine symptom subscale for the FACT-B. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1999, 55, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, K.J.; Eton, D.T. Combining distribution- and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally important differences: The FACIT experience. Eval. Health Prof. 2005, 28, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M.; Sholomskas, D.; Pottenger, M.; Prusoff, B.A.; Locke, B.Z. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1977, 106, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakubo, A.; Oguchi, T. The influence of interaction with others in vacation on subjective happiness and depression. Stress Sci. Res. 2015, 30, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandina, G.; Petrillo, M.; Mantegna, G.; Fuoco, G.; Terzano, S.; Venditti, L.; Marcellusi, A.; De Vincenzo, R.; Scambia, G. Evaluation of quality of life and emotional distress in endometrial cancer patients: A 2-year prospective, longitudinal study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 133, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisman, A.D.; Worden, J.W. The existential plight in cancer: Significance of the first 100 days. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 1976, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.; Sonoda, Y.; Baser, R.E.; Raviv, L.; Chi, D.S.; Barakat, R.R.; Iasonos, A.; Brown, C.L.; Abu-Rustum, N.R. A 2-year prospective study assessing the emotional, sexual, and quality of life concerns of women undergoing radical trachelectomy versus radical hysterectomy for treatment of early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 119, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seol, K.H.; Bong, S.H.; Kang, D.H.; Kim, J.W. Factors Associated with the Quality of Life of Patients with Cancer Undergoing Radiotherapy. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Ninomiya, M.; Maruta, T.; Hosonuma, S.; Yoshioka, N.; Ohara, T.; Nishigaya, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kiguchi, K.; Ishizuka, B. Clinical study on the efficacy of fluvoxamine for psychological distress in gynecologic cancer patients. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Ninomiya, M.; Maruta, S.; Hosonuma, S.; Nishigaya, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kiguchi, K.; Ishizuka, B. Psychological characteristics of Japanese gynecologic cancer patients after learning the diagnosis according to the hospital anxiety and depression scale. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2011, 37, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksson, M.M.; Isometsä, E.T.; Hietanen, P.S.; Aro, H.M.; Lönnqvist, J.K. Mental disorders in cancer suicides. J. Affect. Disord. 1995, 36, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.; Prescott, P.; Mason, J.; McLeod, N.; Lewith, G. Depression and anxiety in ovarian cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromberger, J.T.; Harlow, S.; Avis, N.; Kravitz, H.M.; Cordal, A. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among middle-aged women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1378–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Ohno, T.; Noguchi, W.; Matsuda, A.; Matsushima, E.; Kato, S.; Tsujii, H. Psychological distress and quality of life in cervical cancer survivors after radiotherapy: Do treatment modalities, disease stage, and self-esteem influence outcomes? Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2009, 19, 1264–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.O. Cultural scripts for a good death in Japan and the United States: Similarities and differences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimori, M.; Uchitomi, Y. Preferences of cancer patients regarding communication of bad news: A systematic literature review. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 39, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.C.; Geary, N.; Marchini, A.; Tross, S. An international survey of physician attitudes and practice in regard to revealing the diagnosis of cancer. Cancer Investig. 1987, 5, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akabayashi, A.; Fetters, M.D.; Elwyn, T.S. Family consent, communication, and advance directives for cancer disclosure: A Japanese case and discussion. J. Med. Ethics 1999, 25, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidou, K.; Parpa, E.; Tsilila, E.; Katsouda, E.; Vlahos, L. Cancer information disclosure in different cultural contexts. Support. Care Cancer 2004, 12, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, K.; Fujii, E.; Ohta, H.; Nakamura, K. Mental health of patients visiting an outpatient menopause clinic. Int. J. Fertil. Women’s Med. 2003, 48, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Vivian-Taylor, J.; Hickey, M. Menopause and depression: Is there a link? Maturitas 2014, 79, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasegar, R.; Wolfman, W.; Galan, L.H.; Cullimore, A.; Shea, A.K. Does menopause hormone therapy improve symptoms of depression? Findings from a specialized menopause clinic. Menopause 2024, 31, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.A.; Johnson, K.M. Menopause. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 99, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuursma, A.; Lanjouw, L.; Idema, D.L.; de Bock, G.H.; Mourits, M.J.E. Surgical Menopause and Bilateral Oophorectomy: Effect of Estrogen-Progesterone and Testosterone Replacement Therapy on Psychological Well-being and Sexual Functioning; A Systematic Literature Review. J. Sex. Med. 2022, 19, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, M.; Moss, K.M.; Brand, A.; Wrede, C.D.; Domchek, S.M.; Meiser, B.; Mishra, G.D.; Joffe, H. What happens after menopause? (WHAM): A prospective controlled study of depression and anxiety up to 12 months after premenopausal risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamer, S.; Ozsaran, Z.; Celik, O.; Bildik, O.; Yalman, D.; Bölükbaşi, Y.; Haydaroğlu, A. Evaluation of anxiety levels during intracavitary brachytherapy applications in women with gynecological malignancies. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2007, 28, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, G.; Sumner, B.E.; Rosie, R.; Grace, O.; Quinn, J.P. Estrogen control of central neurotransmission: Effect on mood, mental state, and memory. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1996, 16, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyola, M.G.; Handa, R.J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes: Sex differences in regulation of stress responsivity. Stress 2017, 20, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.H.; Brinton, R.D.; Schmidt, P.J.; Gore, A.C. Estrogen, menopause, and the aging brain: How basic neuroscience can inform hormone therapy in women. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10332–10348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, W. Cancer-related psychosocial challenges. Gen. Psychiatr. 2022, 35, e100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deli, T.; Orosz, M.; Jakab, A. Hormone Replacement Therapy in Cancer Survivors—Review of the Literature. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020, 26, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearman, T. Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in gynecologic cancer survivors. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.C., 3rd. Breast Cancer Survivors, Common Markers of Inflammation, and Exercise: A Narrative Review. Breast Cancer 2017, 11, 1178223417743976. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, K.; Ohno, S.; Takahashi, N.; Suzuki, N.; Nozaki, N.; Murakami, K.; Sugiura, K.; Yamada, K.; Inoue, M. Efficacy of the herbal medicine Unkei-to as an adjunctive treatment to hormone replacement therapy for postmenopausal women with depressive symptoms. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2004, 27, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, G.; Carlomagno, G.; Unfer, V.; D’Anna, R. Myo-inositol: From induction of ovulation to menopausal disorder management. Minerva Ginecol. 2015, 67, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Katyal, G.; Kaur, G.; Ashraf, H.; Bodapati, A.; Hanif, A.; Okafor, D.K.; Khan, S. Systematic Review of the roles of Inositol and Vitamin D in improving fertility among patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2024, 51, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papatheodorou, A.; Vanderzwalmen, P.; Panagiotidis, Y.; Petousis, S.; Gullo, G.; Kasapi, E.; Goudakou, M.; Prapas, N.; Zikopoulos, K.; Georgiou, I.; et al. How does closed system vitrification of human oocytes affect the clinical outcome? A prospective, observational, cohort, noninferiority trial in an oocyte donation program. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, S.; Anazodo, A. The psychological importance of fertility preservation counseling and support for cancer patients. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piergentili, R.; Marinelli, E.; Cucinella, G.; Lopez, A.; Napoletano, G.; Gullo, G.; Zaami, S. miR-125 in Breast Cancer Etiopathogenesis: An Emerging Role as a Biomarker in Differential Diagnosis, Regenerative Medicine, and the Challenges of Personalized Medicine. Non-Coding RNA 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piergentili, R.; Gullo, G.; Basile, G.; Gulia, C.; Porrello, A.; Cucinella, G.; Marinelli, E.; Zaami, S. Circulating miRNAs as a Tool for Early Diagnosis of Endometrial Cancer-Implications for the Fertility-Sparing Process: Clinical, Biological, and Legal Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, S.I.; Kim, S.Y.; Lim, W.J. Insomnia, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients First Diagnosed with Female Cancer. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, W.; Vodermaier, A.; Mackenzie, R.; Greig, D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cull, A.; Cowie, V.J.; Farquharson, D.I.; Livingstone, J.R.; Smart, G.E.; Elton, R.A. Early stage cervical cancer: Psychosocial and sexual outcomes of treatment. Br. J. Cancer 1993, 68, 1216–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandina, G.; Mantegna, G.; Petrillo, M.; Fuoco, G.; Venditti, L.; Terzano, S.; Moruzzi, C.; Lorusso, D.; Marcellusi, A.; Scambia, G. Quality of life and emotional distress in early stage and locally advanced cervical cancer patients: A prospective, longitudinal study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 124, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasada, I.; Eguchi, H.; Kurita, M.; Kudo, S.; Shishida, T.; Mishima, Y.; Saito, Y.; Ushiorozawa, N.; Seto, T.; Shimozuma, K.; et al. Anemia affects the quality of life of Japanese cancer patients. Tokai J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2013, 38, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pignata, S.; Ballatori, E.; Favalli, G.; Scambia, G. Quality of life: Gynaecological cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2001, 12 (Suppl. 3), S37–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.M.; Ngan, H.Y.; Yip, P.S.; Li, B.Y.; Lau, O.W.; Tang, G.W. Psychosocial adjustment in gynecologic cancer survivors: A longitudinal study on risk factors for maladjustment. Gynecol. Oncol. 2001, 80, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | SH (N = 47) | SM (N = 54) | NM (N = 54) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median (range) | 41 (27–53) | 48 (28–56) | 59 (50–73) | <0.001 * |

| <40 | 19 (40.4%) | 5 (9.3%) | 0 | |

| 40–49 | 26 (55.3%) | 27 (50.0%) | 0 | |

| 50–59 | 2 (4.3%) | 22 (40.7%) | 23 (42.6%) | |

| ≥60 | 0 | 0 | 31 (57.4%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Median (range) | 23.2 (16.5–48.1) | 25.3 (16.8–51.3) | 23.7 (17.2–38.8) | 0.240 |

| <25 | 32 (68.1%) | 26 (48.1%) | 31 (57.4%) | |

| 25–30 | 7 (14.9%) | 17 (31.5%) | 12 (22.2%) | |

| >30 | 8 (17.0%) | 11 (20.4%) | 11 (20.4%) | |

| Cancer type and FIGO stage | 0.006 * | |||

| Endometrial cancer | 21 (44.7%) | 40 (74.1%) | 40 (74.1%) | |

| 0:1, I:17, II:1, III:1, IV:1 | 0:3, I:28, II:4, III 5, IV:0 | 0:0, I:33, II:3, III:2, IV:2 | ||

| Cervical cancer | 22 (46.8%) | 8 (14.8%) | 8 (14.8%) | |

| I:13, II:7, III:2, IV:0 | I:4, II:4, III:0, IV:0 | I:5, II:3, III:0, IV:0 | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 5 (10.6%) | 10 (18.5%) | 7 (13.0%) | |

| I:2, II:1, III:2, IV:0 | I:6, II:2, III:2, IV:0 | I:2, II:2, III:3, IV:0 | ||

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Laparoscopic or robotic surgery | 16 (34.0%) | 26 (48.1%) | 30 (55.6%) | 0.089 |

| Laparotomy | 31 (66.0%) | 28 (51.9%) | 24 (44.4%) | |

| Treatment of lymph node | ||||

| None or biopsy | 14 (29.8%) | 29 (53.7%) | 29 (53.7%) | 0.026 * |

| Lymph node dissection | 33 (70.2%) | 25 (46.3%) | 25 (46.3%) | |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 11 (23.4%) | 21 (38.9%) | 20 (37.0%) | 0.141 |

| Radiotherapy | 12 (25.5%) | 5 (9.3%) | 6 (11.1%) | |

| None | 24 (51.1%) | 28 (51.9%) | 28 (51.9%) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 32 (68.1%) | 32 (59.3%) | 48 (88.9%) | 0.001 * |

| Unmarried | 15 (31.9%) | 22 (40.7%) | 6 (11.1%) | |

| Number of children | ||||

| One or more children | 28 (59.6%) | 33 (61.1%) | 43 (79.6%) | 0.053 |

| No children | 19 (40.4%) | 21 (38.9%) | 11 (20.4%) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Smoker | 7 (14.9%) | 9 (16.7%) | 4 (7.4%) | 0.314 |

| Non-smoker | 40 (85.1%) | 45 (85.3%) | 50 (92.6%) |

| Improved or Maintained QOL | Maintained Non-Depression Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81 (80.2%) | 81 (80.2%) | |||

| Independent Variable | N | p-Value | N | p-Value |

| Group | ||||

| SH | 37 | 0.805 | 39 | 0.619 |

| SM | 44 | 42 | ||

| Age | ||||

| <45 years | 38 | 0.809 | 39 | 1.000 |

| ≥45 years | 43 | 42 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| <25 | 47 | 0.620 | 47 | 0.620 |

| ≥25 | 34 | 34 | ||

| Cancer type | ||||

| Endometrioid cancer | 46 | 47 | ||

| Cervical cancer | 23 | 1.000 | 23 | 0.649 |

| Ovarian cancer | 12 | 11 | ||

| FIGO stage | ||||

| Early stage | 56 | 0.786 | 59 | 0.283 |

| Late stage | 25 | 22 | ||

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Laparoscopic or robotic surgery | 35 | 0.616 | 33 | 0.802 |

| Laparotomy | 46 | 48 | ||

| Treatment of lymph node | ||||

| Lymph node dissection | 36 | 0.614 | 46 | 1.000 |

| None or biopsy | 45 | 35 | ||

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Chemotherapy or radiotherapy | 40 | 0.805 | 38 | 0.620 |

| None | 41 | 43 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 52 | 0.798 | 54 | 0.199 |

| Unmarried | 29 | 27 | ||

| Number of children | ||||

| One or more children | 47 | 0.445 | 55 | 0.004 * |

| No children | 34 | 26 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Smoker | 14 | 0.732 | 12 | 0.516 |

| Non-smoker | 67 | 69 | ||

| Independent Variable | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO stage | ||

| Early stage | 1.89 (0.641–5.59) | 0.248 |

| Late stage | 1 (ref) | |

| Number of children | ||

| One or more children | 5.04 (1.72–14.8) | 0.003 * |

| No children | 1 (ref) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karakida, N.; Yanazume, S.; Uchida, N.; Sakihama, M.; Douchi, T.; Kobayashi, H. Changes in Quality of Life, Depression, and Menopausal Symptoms After Surgical Menopause and the Efficacy of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Gynecological Cancer Survivors: A One-Year Prospective Longitudinal Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071191

Karakida N, Yanazume S, Uchida N, Sakihama M, Douchi T, Kobayashi H. Changes in Quality of Life, Depression, and Menopausal Symptoms After Surgical Menopause and the Efficacy of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Gynecological Cancer Survivors: A One-Year Prospective Longitudinal Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071191

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarakida, Noriko, Shintaro Yanazume, Natsuko Uchida, Mika Sakihama, Tsutomu Douchi, and Hiroaki Kobayashi. 2025. "Changes in Quality of Life, Depression, and Menopausal Symptoms After Surgical Menopause and the Efficacy of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Gynecological Cancer Survivors: A One-Year Prospective Longitudinal Study" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071191

APA StyleKarakida, N., Yanazume, S., Uchida, N., Sakihama, M., Douchi, T., & Kobayashi, H. (2025). Changes in Quality of Life, Depression, and Menopausal Symptoms After Surgical Menopause and the Efficacy of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Gynecological Cancer Survivors: A One-Year Prospective Longitudinal Study. Medicina, 61(7), 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071191