1. Introduction

Post-partum depression (PPD) is a mood disorder that emerges within 12 months of childbirth and is characterised by sustained low mood, anhedonia, and impaired functioning [

1,

2]. A 2021 synthesis of 565 population-based studies (

n = 1,236,365) calculated a pooled prevalence of 17.22% for post-partum depression (PPD) worldwide, confirming that roughly one in six new mothers experience clinically significant affective symptoms [

1]. Romanian data are scarce, yet a 2024 hospital-based survey in the country’s south-eastern region reported 16.1% of mothers above the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) threshold, essentially mirroring the global estimate and underscoring an evidence gap in Eastern Europe [

2]. Beyond maternal suffering, untreated PPD erodes caregiving quality and heightens the risk of sub-optimal neuro-cognitive and socio-emotional trajectories in children [

3]. Notably, a U.S. Pregnancy-Risk-Assessment follow-up showed that 7.2% of mothers who were asymptomatic at six months developed new-onset depressive symptoms at 9–10 months, highlighting the disorder’s persistence and latent onset [

4].

The five-factor model suggests that high neuroticism and low extraversion sensitize individuals to stress. A 2022 meta-analysis covering 31 studies confirmed that these traits exert medium effect sizes on postpartum mood (pooled OR_neuroticism = 2.15) [

5], while a 2024 Romanian systematic review using NEO-FFI converged on the same pattern, pointing to culturally stable associations [

6].

Perinatal anxiety disorders frequently co-occur with, or precede, depressive episodes. Dennis et al. pooled 102 studies and found trimester-specific anxiety prevalences of 18–25%, with a clear uptick in late pregnancy and early puerperium [

7]. Encouragingly, a 2024 systematic review of 39 randomised trials showed that digitally delivered cognitive behavioural tools reduced both anxiety and EPDS scores (Hedges g = −0.42) [

8]. Moreover, a recent meta-analysis in low- and middle-income countries estimated that 20% of perinatal women meet criteria for a generalised anxiety disorder, and 8% meet criteria for PTSD, underscoring the global scale of the comorbidity [

8,

9]. Taken together, these findings position anxiety as both a prodrome and a modifiable therapeutic window.

Tobacco use remains prevalent among Romanian women of reproductive age, and a 2025 PRAMS analysis linked any third-trimester smoking to a two-fold increase in PPD risk (adjusted OR = 2.01) [

9]. A 2022 meta-analysis of 14 cohort studies likewise demonstrated that regular alcohol intake during pregnancy confers a 46% relative risk elevation [

10]. When multiple psychoactive substances are considered together, a 2023 umbrella review showed a pooled OR of 2.37 for PPD, implying synergistic hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal activation [

11]. Beyond substance use, exposure to major life events in the year surrounding childbirth independently predicts depressive symptomatology, as confirmed by a 2023 prospective cohort in 11 cities across China [

12].

Perceived emotional and instrumental support during gestation exerts a robust protective effect; a 2024 Polish prospective study showed that each standard-deviation increase on the Berlin Social Support Scales lowered the odds of PPD by 28% [

13]. Conversely, biomedical exposures yield mixed findings; meta-analytic evidence now indicates a modest but significant excess risk after Caesarean delivery (pooled OR = 1.24) [

14], while the severity of prematurity (very versus moderate preterm) predicts distinct depressive trajectories over the first postpartum year [

15]. Emerging mechanistic work links elevated interleukin-6, tumour-necrosis-factor-α, and kynurenine pathway metabolites to perinatal mood disorders [

16], whereas an umbrella review of antenatal depression situates maternal inflammation and anaemia among adverse-birth-outcome pathways [

17]. A high-credibility umbrella review further ranks pre-menstrual syndrome, violent experiences, and unintended pregnancy as the most firmly established psychosocial antecedents [

18].

Universal EPDS implementation at 4–6 weeks postpartum is feasible and achieves 80% coverage in French maternity wards [

19,

20]. Nearly three in five women who manifest depressive symptoms at 9–10 months would have been missed by early screening [

4]. The coexistence of dispositional, symptomatic, behavioural, and obstetric factors therefore mandates an integrative predictive model.

The present investigation simultaneously profiles personality traits, antenatal anxiety trajectories, substance-use patterns, life-event exposure, obstetric/neonatal outcomes, and social-support metrics in a rigorously matched Romanian cohort. By quantifying their individual and interactive contributions, we aim to refine risk stratification and identify leverage points for culturally attuned intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A single-centre study was conducted at the Psychiatry Unit of the “Pius Brinzeu” Clinical Emergency Hospital, affiliated with the “Victor Babeș” University of Medicine and Pharmacy from Timișoara (approval number 299 from 11 May 2022). The study period spanned between July 2022 and July 2024. The study tracked pregnant women from late gestation (28–36 weeks, T0) to six weeks post-partum (T1), whereas the control cohort comprised non-pregnant, age-matched women recruited contemporaneously from the same metropolitan area. All eligible women received a verbal explanation of study aims and procedures and then signed a written informed-consent form approved by the institutional Ethics Committee.

2.2. Participants and Sampling

Eligible respondents were women aged eighteen years or older who were fluent in Romanian and able to complete self-report questionnaires without assistance. Exclusion criteria included current psychotic disorders, severe medical comorbidities, or obstetric complications necessitating intensive care. Pregnant candidates were approached consecutively during routine antenatal visits, whereas controls responded to community advertisements and were screened to exclude ongoing or recent pregnancy. Age matching employed a greedy nearest-neighbor algorithm in R (MatchIt v4.5), pairing each pregnant woman with a control within two years of age, which yielded two cohorts of 102 participants each. Retention in the peripartum cohort was excellent; 100 of the 102 women completed the post-partum assessment by home visit or secure video call a mean ± SD of 42 ± 5 days after delivery.

2.3. Measures

The principal outcome was post-partum depression measured by the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale (EPDS) [

21], a ten-item questionnaire scored from zero to thirty; scores of twelve or higher were interpreted as indicative of clinically significant depression, consistent with Romanian validation studies. Psychological predictors were captured with several instruments. State and trait anxiety were evaluated using the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory, Form Y (STAI-Y) [

22], whose two twenty-item subscales each yield scores from twenty to eighty. Personality traits were measured with the NEO Five-Factor Inventory-60 (NEO-FFI-60) [

23], which contains twelve items per trait and provides raw totals that were converted to age- and sex-referenced T-scores according to Romanian norms. Obsessive–compulsive symptom dimensions were assessed with the eighteen-item Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory–Revised (OCI-R) [

24], producing totals from zero to seventy-two. Perceived worry and satisfaction were quantified with the Maternal Worry and Satisfaction Scale (MWSS) [

25], which consists of four visual analogue items anchored at zero (no worry or dissatisfaction) and ten (maximal worry or satisfaction). Internal consistency estimates in the present sample were strong, with Cronbach’s α equal to 0.89 for the EPDS, 0.92 and 0.90 for the STAI-Y state and trait subscales respectively, 0.88 for the OCI-R, and 0.81 for the MWSS; values for NEO-FFI domains were all at least 0.78.

Behavioural and obstetric covariates were documented to control for potential confounding. Current smoking was defined as at least one cigarette per day during the preceding month, and current alcohol use was defined as any weekly consumption over the same period. Recent stress exposure was coded dichotomously when participants reported at least one major life event, such as bereavement, job loss, or relationship dissolution, in the past twelve months. Obstetric information—gestational age at delivery, birth weight, prematurity defined as delivery before thirty-seven weeks, delivery mode (vaginal versus caesarean section), newborn sex, and five-minute Apgar score—was extracted from electronic medical records to ensure accuracy.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted in Python using SciPy 1.12 for basic statistics; Statsmodels 0.15 was used for regressions, and Pingouin 0.5 was used for effect-size calculations. The normality of continuous variables was inspected with the Shapiro–Wilk test, while the equality of variances was assessed via Levene’s test. Between-group differences for continuous outcomes were examined with independent-sample t-tests, and categorical comparisons employed Pearson’s chi-square test. Within-subject changes from T0 to T1 in the pregnant cohort, notably for anxiety and depressive symptoms, were analysed with paired-sample t-tests. Pearson product–moment correlations mapped associations among psychological variables, with the experiment-wise alpha set at 0.01 after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Variables displaying bivariate associations with clinically significant post-partum depression (EPDS ≥ 12) at p < 0.10 were simultaneously entered into a logistic-regression model using the enter method. Model adequacy was judged by Nagelkerke pseudo-R2, the likelihood-ratio chi-square statistic, and the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Variance inflation factors confirmed the absence of problematic multicollinearity, as all VIFs were below 2. Effect sizes for mean differences were expressed as Cohen’s d, contingency associations as Cramer’s V, and regression results as odds ratios with ninety-five percent confidence intervals. Statistical significance was interpreted at two-tailed p < 0.05 unless stated otherwise. An a priori calculation performed with G*Power 3.1 indicated that the available sample of 102 participants per group afforded eighty-percent power to detect medium-sized effects (Cohen’s d ≥ 0.50 or odds ratio ≥ 2.0) at an alpha of 0.05.

3. Results

Compared with age-matched controls (30.3 ± 5.1 years), peripartum participants were marginally older (31.1 ± 5.4 years;

p = 0.268) but displayed the following distinctly different contextual profile: urban residence was less common (39% vs. 83%, χ

2 = 11.7,

p = 0.001), university education was slightly lower (66% vs. 77%,

p = 0.123), and formal employment was nominally higher (81% vs. 71%,

p = 0.101). Critically, only 16% of peripartum women reported at least one stressful life event in the preceding 12 months versus 50% of controls (χ

2 = 24.2,

p < 0.001), while current smoking (21% vs. 34%,

p = 0.041) and alcohol use (6% vs. 22%,

p = 0.002) were substantially lower, suggesting pregnancy-related lifestyle modification and differential exposure to psychosocial adversity (

Table 1).

Psychological baselines were largely comparable across cohorts; neither state anxiety (35.0 ± 12.8 vs. 38.1 ± 11.4,

p = 0.140), trait anxiety (39.8 ± 13.4 vs. 38.9 ± 10.8,

p = 0.605), nor obsessive–compulsive symptom load (26.5 ± 12.7 vs. 24.1 ± 11.9,

p = 0.118) differed significantly. Personality scores were likewise homogeneous, with neuroticism (20.4 ± 7.4 vs. 21.5 ± 7.0,

p = 0.295), extraversion (28.3 ± 5.3 vs. 27.1 ± 6.2,

p = 0.140), agreeableness (33.2 ± 6.1 vs. 32.5 ± 5.9,

p = 0.380), and conscientiousness (36.5 ± 6.1 vs. 35.2 ± 6.4,

p = 0.136) showing no meaningful divergence. The single exception was openness, which was 3.2 points lower in peripartum women (26.1 ± 4.6) than controls (29.3 ± 5.2), a medium effect reaching high significance (

p < 0.001), indicating selective attenuation of exploratory cognitive tendencies during late pregnancy (

Table 2).

Over the six-week transition from late gestation to early puerperium, depressive symptoms rose from a mean EPDS of 8.1 ± 4.8 to 9.6 ± 5.5 (paired t = 3.90,

p < 0.001), with 36% surpassing the clinical threshold (≥12). State anxiety showed an even steeper increase, climbing 5.0 points (35.0 ± 12.8 to 40.0 ± 14.7; t = 6.10,

p < 0.001), whereas trait anxiety exhibited only a marginal, non-significant 1.4-point rise (

p = 0.051). Obsessive–compulsive symptoms escalated by 4.2 points (26.5 ± 12.7 to 30.7 ± 14.2; t = 6.82,

p < 0.001). Partner–relationship satisfaction decreased modestly yet significantly (8.2 ± 1.5 to 7.8 ± 1.8; t = −2.54,

p = 0.013), underscoring multifaceted psychological strain in the early post-partum period (

Table 3).

Obstetric variables showed limited association with post-partum depression severity. Women with an EPDS ≥ 12 delivered at a comparable gestational age (38.1 ± 1.9 weeks) to their lower-EPDS counterparts (38.4 ± 1.5 weeks;

p = 0.358), and preterm birth rates did not differ (24% vs. 14%,

p = 0.287). Caesarean delivery prevalence was virtually identical between high- and low-EPDS groups (68% vs. 69%,

p = 0.900). Birth weight trended lower among depressed mothers by 221 g (2904 ± 561 g vs. 3125 ± 520 g;

p = 0.051), while low Apgar scores (<8 at 1 min) were more frequent (16% vs. 5%,

p = 0.105) but did not attain statistical significance, collectively suggesting that obstetric factors play a subordinate role once psychosocial variables are considered (

Table 4).

Pregnant participants reported healthier behaviours, with smoking reduced by 13 percentage points relative to controls (21% vs. 34%; χ

2 = 4.19,

p = 0.041) and alcohol use curtailed to one-quarter of the control rate (6% vs. 22%; χ

2 = 9.45,

p = 0.002). Conversely, exposure to at least one recent stressful life event was three times lower among peripartum women (16% vs. 50%; χ

2 = 24.2,

p < 0.001), aligning with the protective social buffering often observed during pregnancy and potentially moderating psychological risk (

Table 5).

A post hoc comparison based on EPDS stratification revealed that participants with clinically significant depressive symptoms (EPDS ≥ 12) experienced markedly poorer restorative sleep, averaging only 4.8 ± 1.5 h per night versus 6.3 ± 1.2 h in the non-depressed group (

p < 0.001), and they reported substantially greater fatigue, with mean scores of 6.8 ± 2.0 compared to 4.1 ± 1.7 (

p < 0.001). Furthermore, exclusive breastfeeding was less prevalent among those with higher depressive symptoms (40% vs. 60%,

p = 0.042), indicating that elevated postpartum depressive symptomatology is associated with shortened sleep duration, increased fatigue burden, and reduced likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding (

Table 6).

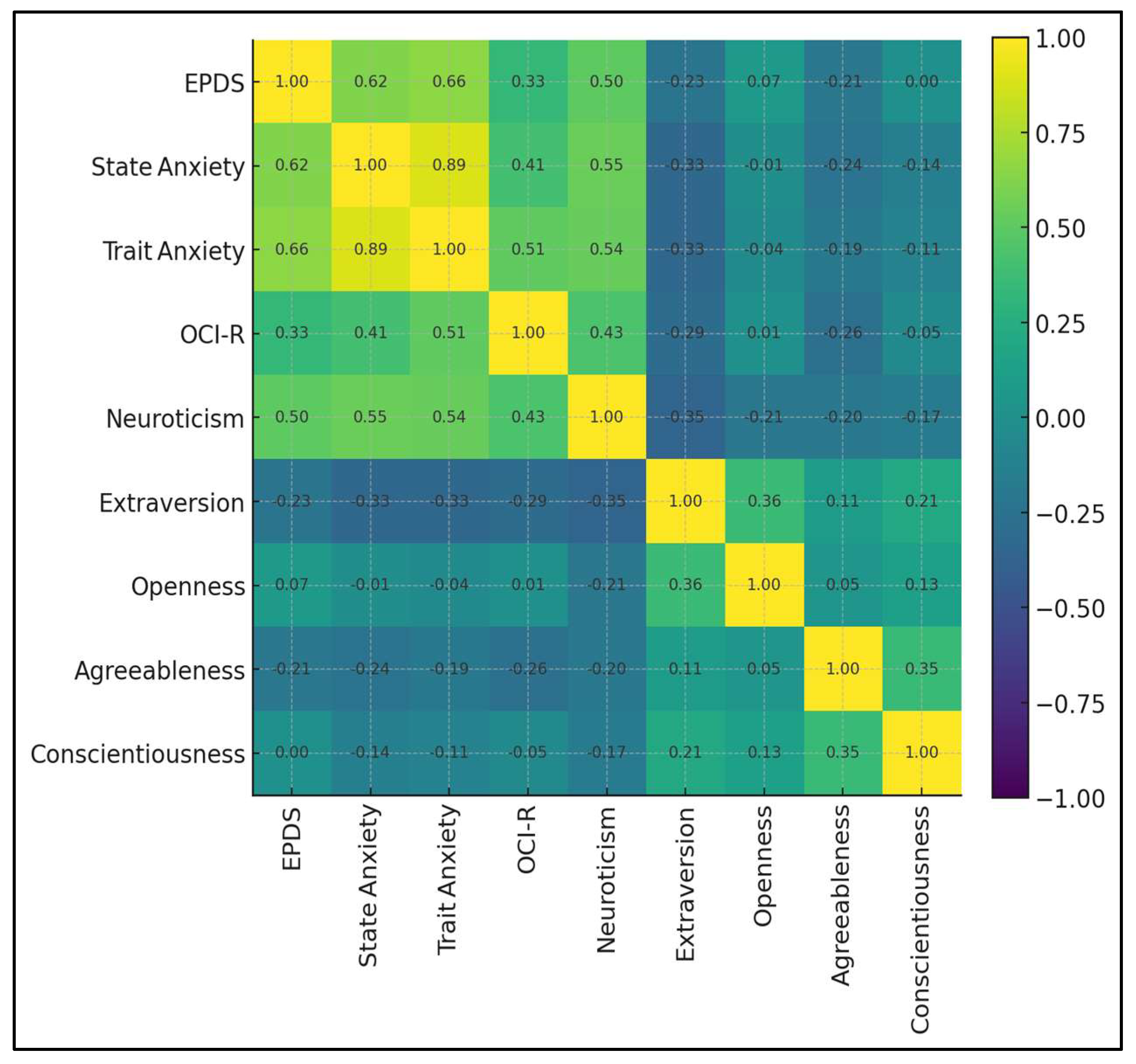

Depression severity correlated most strongly with trait anxiety (

r = 0.66,

p < 0.001) and state anxiety (

r = 0.62,

p < 0.001), together explaining ~44% of EPDS variance. Neuroticism demonstrated a robust association (

r = 0.50), while obsessive–compulsive symptoms contributed a moderate link (

r = 0.33,

p = 0.001). Protective, albeit weaker, inverse relations were observed for extraversion (

r = −0.27,

p = 0.006) and agreeableness (

r = −0.20,

p = 0.045). Openness and conscientiousness were effectively null (|

r| ≤ 0.04,

p > 0.65). After Bonferroni adjustment (α = 0.01), only the anxiety metrics and neuroticism retained significance, highlighting anxiety as the principal modifiable correlation of early PPD (

Table 7).

The dispersion graph reveals the following clear linear trend: postpartum EPDS rises by ≈0.23 points for every additional point on the STAI-State scale (slope = 0.23, 95% CI 0.17–0.29). The Pearson correlation was strong (r = 0.62), accounting for 38.6% of shared variance. Practically, women with situational anxiety below 30 rarely exceeded the clinical EPDS cutoff (12), whereas 83% of those scoring ≥55 on STAI-State crossed that threshold. The dashed line depicting EPDS = 12 highlights this inflection; along the fitted regression, the model predicts the depression boundary at a STAI-State value of roughly 51. These data visualise how incremental anxiety elevations translate into a step-change in depressive risk, underscoring STAI-State as a sensitive screening lever (

Figure 1).

The matrix depicts the inter-relationships among nine postpartum psychological constructs. A high-intensity triangular cluster links trait anxiety, state anxiety, and neuroticism (r = 0.54–0.89), reflecting a core distress dimension. EPDS situates firmly within that cluster, correlating 0.66 with trait anxiety, 0.62 with state anxiety, and 0.50 with neuroticism, but only 0.33 with obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCI-R). Protective associations appear in cooler hues. EPDS correlates negatively with extraversion (r = −0.23) and agreeableness (r = −0.21), while links with openness and conscientiousness hover near zero (

Figure 2).

The final model (χ

2 = 39.96,

df = 3,

p < 0.001; pseudo-R

2 = 0.30) confirmed post-partum state anxiety as a significant predictor; each one-point increase on the STAI-State scale elevated the odds of clinically significant depression by 10% (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.05–1.15,

p < 0.001). Neuroticism approached significance (OR 1.08,

p = 0.081), implying partial mediation through acute anxiety, whereas extraversion exerted no independent effect (OR 1.00,

p = 0.990). Collectively, the model underscores that targeting situational anxiety could yield substantial reductions in PPD incidence, even after accounting for stable personality traits (

Table 8).