Beyond Diagnosis: Exploring Residual Autonomy in Dementia Through a Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cognition and Autonomy: A Complex Relationship

1.2. ADLs as a Measure of Functional Autonomy

1.3. ADL Classification and Progression of Decline

1.4. Study Aims and Influencing Factors

2. Materials and Methods

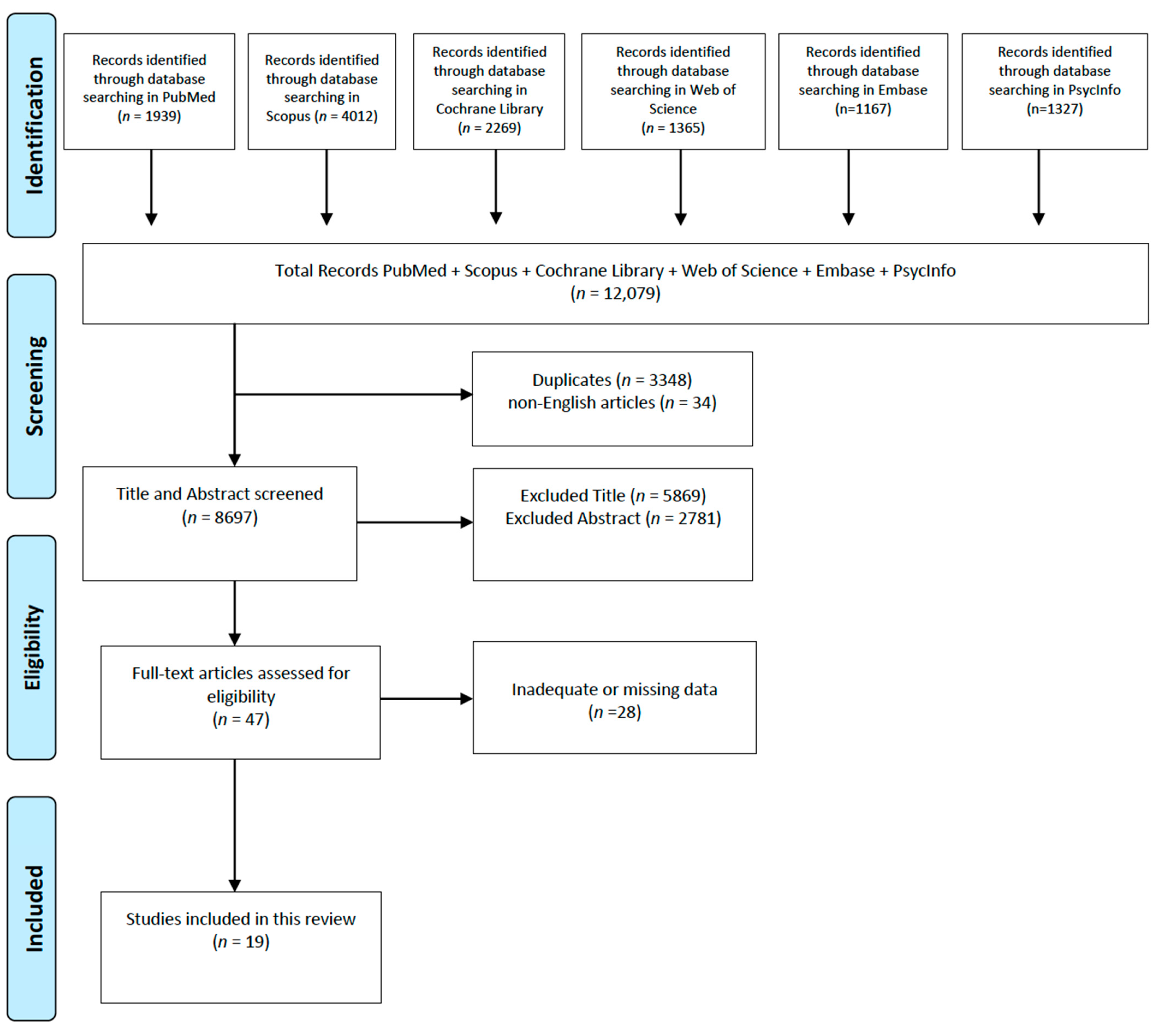

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Study Selection and Quality Assessment

2.3. Measurement

3. Results

3.1. Findings in Non-Institutionalized Settings

3.2. Findings in Institutionalized Settings

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Living Context on Autonomy and Cognitive Functioning

4.2. Variability in Functional Decline and Limitations of Standardized Assessment

4.3. Psychological and Social Determinants of Autonomy

4.4. The Role of Daily Relationships, Home Support, and Innovative Living Solutions

4.5. Clinical Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirova, A.M.; Bays, R.B.; Lagalwar, S. Working memory and executive function decline across normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 748212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigaux, N. Autonomie et démence [Autonomy and dementia]. Geriatr. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil. 2011, 9, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boumans, J.; van Boekel, L.C.; Baan, C.A.; Luijkx, K.G. How Can Autonomy Be Maintained and Informal Care Improved for People with Dementia Living in Residential Care Facilities: A Systematic Literature Review. The Gerontologist 2019, 59, e709–e730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S.E.; Patterson, C.; Feightner, J. Preventing dementia. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. Le. J. Can. Des. Sci. Neurol. 2001, 28 (Suppl. S1), S56–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.K.; Grossberg, G.T.; Sheth, D.N. Activities of daily living in patients with dementia: Clinical relevance, methods of assessment and effects of treatment. CNS Drugs 2004, 18, 853–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkes, S.A.; de Rotrou, J. A qualitative review of instrumental activities of daily living in dementia: What’s cooking? Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2014, 4, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, M.; Cameron, E.; Mansfield, E.; Sanson-Fisher, R. Perceptions of people living with dementia regarding patient-centred aspects of their care and caregiver support. Australas. J. Ageing 2023, 42, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B. A conceptual framework for person-centred practice with older people. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2003, 9, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetherstonhaugh, D.; McAuliffe, L.; Bauer, M.; Shanley, C. Decision-making on behalf of people living with dementia: How do surrogate decision-makers decide? J. Med. Ethics 2017, 43, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ydstebø, A.E.; Bergh, S.; Selbæk, G.; Benth, J.Š.; Brønnick, K.; Vossius, C. Longitudinal changes in quality of life among elderly people with and without dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 1607–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashmdarfard, M.; Azad, A. Assessment tools to evaluate Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) in older adults: A systematic review. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2020, 34, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, M.; Osawa, A.; Kondo, I.; Sakurai, T. Factors associated with cognitive function that cause a decline in the level of activities of daily living in Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikezaki, H.; Hashimoto, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Fukuhara, R.; Tanaka, H.; Yuki, S.; Kuribayashi, K.; Hotta, M.; Koyama, A.; Ikeda, M.; et al. Relationship between executive dysfunction and neuropsychiatric symptoms and impaired instrumental activities of daily living among patients with very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 35, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimokihara, S.; Tabira, T.; Hotta, M.; Tanaka, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Maruta, M.; Han, G.; Ikeda, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Ikeda, M. Differences by cognitive impairment in detailed processes for basic activities of daily living in older adults with dementia. Psychogeriatrics 2022, 22, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlinac, M.E.; Feng, M.C. Assessment of Activities of Daily Living, Self-Care, and Independence. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillioz, A.S.; Villars, H.; Voisin, T.; Cortes, F.; Gillette-Guyonnet, S.; Andrieu, S.; Gardette, V.; Nourhashémi, F.; Ousset, P.J.; Jouanny, P.; et al. Spared and impaired abilities in community-dwelling patients entering the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2009, 28, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mograbi, D.C.; Morris, R.G.; Fichman, H.C.; Faria, C.A.; Sanchez, M.A.; Ribeiro, P.C.C.; Lourenço, R.A. The impact of dementia, depression and awareness on activities of daily living in a sample from a middle-income country. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takechi, H.; Kokuryu, A.; Kubota, T.; Yamada, H. Relative Preservation of Advanced Activities in Daily Living among Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Dementia in the Community and Overview of Support Provided by Family Caregivers. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 2012, 418289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Votruba, K.L.; Persad, C.; Giordani, B. Patient Mood and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Alzheimer Disease: Relationship Between Patient and Caregiver Reports. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aske, D. The correlation between Mini-Mental State Examination scores and Katz ADL status among dementia patients. Rehabil. Nurs. 1990, 15, 140–142+146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Nagata, Y.; Ishimaru, D.; Ogawa, Y.; Fukuhara, K.; Nishikawa, T. Clinical factors associated with activities of daily living and their decline in patients with severe dementia. Psychogeriatrics 2020, 20, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashizawa, T.; Igarashi, A.; Sakata, Y.; Azuma, M.; Fujimoto, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Takase, Y.; Ikeda, S. Impact of the Severity of Alzheimer’s Disease on the Quality of Life, Activities of Daily Living, and Caregiving Costs for Institutionalized Patients on Anti-Alzheimer Medications in Japan. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 81, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Riccio, D.; Solinas, A.; Astara, G.; Mantovani, G. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in female elderly patients with Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2007, 44 (Suppl. S1), 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, C.K.; Wittrup-Jensen, K.U.; Lolk, A.; Andersen, K.; Kragh-Sørensen, P. Ability to perform activities of daily living is the main factor affecting quality of life in patients with dementia. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tabira, T.; Hotta, M.; Maruta, M.; Ikeda, Y.; Shimokihara, S.; Han, G.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tanaka, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Ikeda, M. Characteristic of process analysis on instrumental activities of daily living according to the severity of cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potashman, M.; Pang, M.; Tahir, M.; Shahraz, S.; Dichter, S.; Perneczky, R.; Nolte, S. Psychometric properties of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study—Activities of Daily Living for Mild Cognitive Impairment (ADCS-MCI-ADL) scale: A post hoc analysis of the ADCS ADC-008 trial. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.P.; Chan, C.C.; Chu, M.M.; Ng, T.Y.; Chu, L.W.; Hui, F.S.; Yuen, H.K.; Fisher, A.G. Activities of daily living performance in dementia. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2007, 116, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.M.; Sutcliffe, C.; Stolt, M.; Karlsson, S.; Renom-Guiteras, A.; Soto, M.; Verbeek, H.; Zabalegui, A.; Challis, D. Deterioration of basic activities of daily living and their impact on quality of life across different cognitive stages of dementia: A European study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, D.A. An examination of instrumental activities of daily living assessment in older adults and mild cognitive impairment. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2012, 34, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechowski, L.; de Stampa, M.; Denis, B.; Tortrat, D.; Chassagne, P.; Robert, P.; Teillet, L.; Vellas, B. Patterns of loss of abilities in instrumental activities of daily living in Alzheimer’s disease: The REAL cohort study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2008, 25, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, S.E.; Doody, R.; Li, H.; McRae, T.; Jambor, K.M.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Perdomo, C.A.; Richardson, S. Donepezil preserves cognition and global function in patients with severe Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2007, 69, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgon, C.; Goldberg, S.; van der Wardt, V.; Harwood, R.H. Experiences and understanding of apathy in people with neurocognitive disorders and their carers: A qualitative interview study. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.; Broekharst, D.S.E.; de Boer, B.; Groen, W.G.; Verbeek, H. An overview of innovative living arrangements within long-term care and their characteristics: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boller, F.; Verny, M.; Hugonot-Diener, L.; Saxton, J. Clinical features and assessment of severe dementia. A review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2002, 9, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panisset, M.; Roudier, M.; Saxton, J.; Boller, F. Severe Impairment Battery. A neuropsycho- logical test for severly demented patients. Arch. Neurol. 1994, 51, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, S.R.; Sclan, S.G.; Yaffee, R.A.; Reisberg, B. The neglected half of Alzheimer disease: Cognitive and functional concomitants of se- vere dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1994, 42, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán-Calenti, J.C.; Tubío, J.; Pita-Fernández, S.; Rochette, S.; Lorenzo, T.; Maseda, A. Cognitive impairment as predictor of functional dependence in an elderly sample. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 54, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Elliott, S.; Fielding, L. Is there a relationship between Mini-Mental Status Examination scores and the activities of daily living abilities of clients presenting with suspected dementia. Phys. Occup. Ther. Geriatr. 2014, 32, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.T.S.; Yu, M.L.; Brown, T.; Andrews, H. Association between older adults’ functional performance and their scores on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Ir. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 46, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, S.; Maggi, G.; Ilardi, C.R.; Cavallo, N.D.; Torchia, V.; Pilgrom, M.A.; Cropano, M.; Roldán-Tapia, M.D.; Santangelo, G. The relation between cognitive functioning and activities of daily living in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: A meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2427–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, E.; Pinquart, M. How Effective Are Dementia Caregiver Interventions? An Updated Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martyr, A.; Clare, L. Executive function and activities of daily living in Alzheimer’s disease: A correlational meta-analysis. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2012, 33, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T. Person and process in dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1993, 8, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, J.M.; Sabat, S.R. Stereotypes, stereotype threat and ageing: Implications for the understanding and treatment of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Soc. 2008, 28, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Lewis, P. Recognition memory in elderly patients with depression and dementia: A signal detection analysis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1977, 86, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moheb, N.; Mendez, M.F.; Kremen, S.A.; Teng, E. Executive Dysfunction and Behavioral Symptoms Are Associated with Deficits in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Frontotemporal Dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2017, 43, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Norton, L.E.; Malloy, P.F.; Salloway, S. The impact of behavioral symptoms on activities of daily living in patients with dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2001, 9, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, G.I.; Hastie, C.L.; Morris, J.N.; Fries, B.E.; Ankri, J. Measuring change in activities of daily living in nursing home residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatr. 2006, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McConnell, E.S.; Pieper, C.F.; Sloane, R.J.; Branch, L.G. Effects of cognitive performance on change in physical function in long-stay nursing home residents. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2002, 57, M778–M784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferson, A.L.; Paul, R.; Ozonoff, A.; Cohen, R. Evaluating elements of executive functioning as predictors of instrumental activities of daily liv- ing (IADL). Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2006, 21, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, S.T.; Harrell, E.; Neumann, C.; Houtz, A. The relationship between neuropsychological performance and daily functioning in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease: Ecological validity of neuropsychological tests. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2003, 18, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AGICH; George, J. Autonomy and Long-Term Care; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, J.; Luijkx, K.; Janssen, M.; de Rooij, I.; Janssen, B. Facilitators and barriers to autonomy: A systematic literature review for older adults with physical impairments, living in residential care facilities. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 1021–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.R.; Vo, H.T.; Johnson, L.A.; Barber, R.C.; O’Bryant, S.E. The Link between Cognitive Measures and ADLs and IADL Functioning in Mild Alzheimer’s: What has Gender Got to Do with It? Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011, 2011, 276734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, G.; Danti, S.; Picchi, L.; Nuti, A.; Fiorino, M.D. Daily functioning and dementia. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2020, 14, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, C.J.; Bayer, A.; Beaupre, L.; Clare, L.; Poulos, R.G.; Wang, R.H.; Zuidema, S.; McGilton, K.S. A comprehensive approach to reablement in dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2017, 3, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sde Vocht, H.M.; Hoogeboom, A.M.; van Niekerk, B.; den Ouden, M.E. The impact of individualized interaction on the quality of life of elderly dependent on care as a result of dementia: A study with a pre-post design. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2015, 39, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaugler, J.E.; Yu, F.; Krichbaum, K.; Wyman, J.F. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med. Care 2009, 47, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Wirtz, P.W. Characteristics of adult day care participants who enter a nursing home. Psychol. Aging 2007, 22, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappadona, I.; Corallo, F.; Cardile, D.; Ielo, A.; Bramanti, P.; Lo Buono, V.; Ciurleo, R.; D’Aleo, G.; De Cola, M.C. Audit as a Tool for Improving the Quality of Stroke Care: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Objective | Sample | Tools | Context | ADL Results | Dementia Severity | Preserved Autonomies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aske, 1990 [21] | To compare scores obtained through the Mini-Mental and ADL autonomy scales | 37 subjects | MMSE ADL | Rehabilitation center for dementia patients | There is a negative correlation between Mini-Mental and ADL scores. That is, the higher the Mini-Mental score, the lower the ADL score. | Missing | NO autonomies |

| Votruba et al., 2015 [19] | To investigate the relationship between self-reported depressive symptoms and caregiver-perceived depressive symptoms with ADLs | 71 subjects | MMSE WMS-III GDS-15 ADL IADL | Institutionalized | Depressive symptoms were associated with worse performance on IADL measurements. | Mild dementia (mean MMSE = 19.86) | NO autonomies |

| Tanaka et al., 2020 [22] | To identify clinical factors influencing ADLs at baseline and after 6 months | 131 subjects | PSMS MMSE CTSD | Hospital setting (institutionalized) | Only cognitive function assessed by CTSD at baseline was associated with ADLs. | Mild to moderate dementia: 38 patients; severe dementia: 93 patients | NO autonomies |

| Ashizawa et al., 2021 [23] | To evaluate the impact of Alzheimer’s disease severity on ADLs, QoL, and care costs in Japanese elderly care facilities | 287 subjects | EQ-5D-5L BI MMSE | Institutionalized | With worsening AD severity, BI scores significantly decreased. | Mild: 53 patients; moderate: 118 patients; severe: 116 patients | NO autonomies |

| Riccio et al., 2007 [24] | To assess whether decline in cognitive functions is associated with functional deterioration | 47 subjects | ADL IADL MMSE CGA | Institutionalized | MMSE was significantly correlated with dependence in ADLs. | Severe dementia (MMSE 0–9): 5 patients; moderate dementia (MMSE 10–29): 23 patients; mild dementia (MMSE 20–30): 19 patients | NO autonomies |

| Ikezaki et al., 2020 [13] | To examine the relationship between global cognitive functions, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and IADLs in patients with mild AD | 230 subjects | ADAS-Jcog FAB GDS-15 ADL MMSE NPI CDR | Hospital setting (non-institutionalized) | Apathy on NPI was associated with numerous IADL elements. Preserved autonomies in men were phone use (95.8%), transportation (94.4%), financial skills (94.4%). In women, phone use (99.4%), housekeeping (91.8%), laundry (92.5%), transportation (83.6%), financial skills (90.6%). | All patients scored ≥ 21 on MMSE (mild Alzheimer’s) | YES autonomies |

| Takechi et al., 2012 [18] | To analyze the decline of different types of ADLs (BADL, IADL, and AADL) | 39 subjects | MMSE ADL IADL AADL BADL | Hospital setting (non-institutionalized) | Physical ambulation and feeding remained preserved. Mean MMSE score: 22.3 ± 3.4. | Missing | YES autonomies |

| Andersen et al., 2004 [25] | To identify key factors influencing QoL related to health in dementia patients | 244 subjects | CDR MMSE ADL EQ-5D | Non-institutionalized | Overall, 16% classified as dependent, 84% classified as independent in ADL performance. | Mild: 140 (57.4%); moderate: 74 (30.4%); severe: 30 (12.3%) | YES autonomies |

| Gillioz et al., 2009 [16] | To evaluate characteristics of patients in severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease | 126 subjects | MMSE SIB ADL IADL MNA | Non-institutionalized (outpatient) | Overall, 6.5% were totally independent in BADLs, 71% were completely independent in mobility, 53.2% in feeding, 46.8% in toileting, and 41.1% in continence. Mean MMSE score: 7.0 ± 2.2. Mean SIB score: 69.7 ± 16.9. | Missing | YES autonomies |

| Tabira et al., 2024 [26] | To assess compromised and intact IADLs with severity of cognitive decline in elderly with Alzheimer’s disease | 115 subjects | MMSE IADL | Non-institutionalized | Use of transportation means, financial management, telephone use, and medication management were preserved and independent of cognitive decline. | Missing | YES autonomies |

| Shimokihara et al., 2022 [14] | To clarify characteristics of processes for BADLs with severity of cognitive decline in elderly with dementia | 143 subjects | MMSE PADA-D | Non-institutionalized | Some ADLs remained preserved. Feeding: 94.8%. Toileting: 87.2%. Dressing: 73.6%. Personal care: 65.2%. Mobility: 81.4%. Bathing: 72.8%. | Mild: 53 patients; moderate: 73 patients; severe: 17 patients | YES autonomies |

| Potashman et al., 2023 [27] | To evaluate the measurement properties of ADCS-ADL-MCI in subjects with cognitive decline | 769 subjects | ADCS ADL MMSE | Non-institutionalized | At baseline, about two-thirds of the individual items showed ceiling effects, with over 80% of patients performing daily activities “without supervision”. By month 36, most of these ceiling effects persisted, though to a lesser extent, which were no longer evident for items 1, 10, and 11. | Mild cognitive impairment: 58% (MMSE = 27,7) | YES autonomies |

| Liu et al., 2007 [28] | To explore the activities of daily living ADL performance profile of community-living people with dementia and to investigate its relationship with dementia severity | 86 subjects | CDR IADL | Non-institutionalized | Subjects were generally able to perform most basic BADLs, including personal care, feeding, dressing, and using the bathroom. For basic IADLs, most subjects were able to perform basic instrumental daily activities ADLs in the household, such as home maintenance and laundry. | Both the median and mode score of the CDR was 1.0 (range 0.5–3.0), indicating that the majority of the subjects had mild dementia | YES autonomies |

| Giebel et al., 2014 [29] | Analyze the impact of deterioration in basic daily activities of living at different stages of dementia | 1026 subjects | MMSE ADL | Non-institutionalized | Bathroom use, transfer, and feeding remained relatively preserved during all stages of dementia. | Mild dementia (n = 263); moderate dementia (n = 521); severe dementia (n = 242) | YES autonomies |

| Reference (Author, Year) | Severity of Dementia | Context | Preserved Autonomy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aske, 1990 [21] | Missing | Institutionalized | No |

| Andersen et al., 2004 [25] | Mild: 140; moderate: 74; severe: 30 | Non-institutionalized | Yes |

| Riccio et al., 2007 [24] | Severe: 5; moderate: 23; mild: 19 | Institutionalized | No |

| Gillioz et al., 2009 [16] | Severe (mean MMSE = 7.0) | Non-institutionalized | Yes |

| Takechi et al., 2012 [18] | Missing | Non-institutionalized | Yes |

| Votruba et al., 2015 [19] | Mild (mean MMSE = 19.86) | Institutionalized | No |

| Ikezaki et al., 2020 [13] | Mild (MMSE ≥ 21) | Non-institutionalized | Yes |

| Tanaka et al., 2020 [22] | Mild–moderate: 38; severe: 93 | Institutionalized | No |

| Ashizawa et al., 2021 [23] | Mild: 53; moderate: 118; severe: 116 | Institutionalized | No |

| Shimokihara et al., 2022 [14] | Mild: 53; moderate: 73; severe: 17 | Non-institutionalized | Yes |

| Potashman et al., 2023 [27] | Mild cognitive impairment (58%) | Non-institutionalized | Yes |

| Tabira et al., 2024 [26] | Missing | Non-institutionalized | Yes |

| Liu et al., 2007 [28] | Mild dementia | Non institutionalized | Yes |

| Giebel et al., 2014 [29] | Mild dementia (n = 263); moderate dementia (n = 521); severe dementia (n = 242) | Non institutionalized | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anselmo, A.; Corallo, F.; Pagano, M.; Cardile, D.; Marra, A.; Maresca, G.; De Luca, R.; Alagna, A.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R.S.; et al. Beyond Diagnosis: Exploring Residual Autonomy in Dementia Through a Systematic Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050895

Anselmo A, Corallo F, Pagano M, Cardile D, Marra A, Maresca G, De Luca R, Alagna A, Quartarone A, Calabrò RS, et al. Beyond Diagnosis: Exploring Residual Autonomy in Dementia Through a Systematic Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(5):895. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050895

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnselmo, Anna, Francesco Corallo, Maria Pagano, Davide Cardile, Angela Marra, Giuseppa Maresca, Rosaria De Luca, Antonella Alagna, Angelo Quartarone, Rocco Salvatore Calabrò, and et al. 2025. "Beyond Diagnosis: Exploring Residual Autonomy in Dementia Through a Systematic Review" Medicina 61, no. 5: 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050895

APA StyleAnselmo, A., Corallo, F., Pagano, M., Cardile, D., Marra, A., Maresca, G., De Luca, R., Alagna, A., Quartarone, A., Calabrò, R. S., & Cappadona, I. (2025). Beyond Diagnosis: Exploring Residual Autonomy in Dementia Through a Systematic Review. Medicina, 61(5), 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050895