Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Challenges Faced by Undergraduate Dental Students During Root Canal Treatment (RCT) and the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients After RCT

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Questionnaires

2.3. Operator-Based Instrument

2.4. Patient-Based Instrument

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic and Patient-Related Factors

4.1.1. Age

4.1.2. Gender

4.1.3. Tooth Type

4.1.4. Pain

4.1.5. Socioeconomic Status

4.2. OHRQoL

4.2.1. OHRQoL Related to Age

4.2.2. OHRQoL Related to Gender

4.2.3. OHRQoL Related to Pain

4.2.4. OHRQoL Associated with RCT on Various Tooth Types

4.2.5. OHRQoL Related to Socioeconomic Status

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Ling, J.; Bian, Z.; Yu, Q.; Hou, B.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Ye, L.; et al. Expert consensus on difficulty assessment of endodontic therapy. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 2024, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammari, F.R.; Alamri, H.; Aljohani, M.; Sabbah, W.; O’Malley, L.; Glenny, A.M. Dental caries in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. J. Taibah. Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Alqhtani, N.R.; Gufran, K.; Aljulayfi, I.S.; Alateek, A.M.; Alotni, S.I.; Aljarad, A.J.; Alhamdi, A.A.; Alotaibi, Y.K. Analysis of Trends in Demographic Distribution of Dental Workforce in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5321628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.K.; Chong, B.S. A web-based endodontic case difficulty assessment tool. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2381–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.B. Difficulties Encountered during Transition from Preclinical to Clinical Endodontics among Salman bin Abdul Aziz University Dental Students. J. Int. Oral. Health 2015, 7, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salam, A.A. Ageing in Saudi Arabia: New dimensions and intervention strategies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakiba, B.; Hamedy, R.; Pak, J.G.; Barbizam, J.V.; Ogawa, R.; White, S.N. Influence of increased patient age on longitudinal outcomes of root canal treatment: A systematic review. Gerodontology. 2017, 34, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilinskaite-Petrauskiene, I.; Haug, S.R. A comparison of endodontic treatment factors, operator difficulties, and perceived oral health-related quality of life between elderly and young patients. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 1844–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomonov, M.; Kim, H.C.; Hadad, A.; Levy, D.H.; Ben Itzhak, J.; Levinson, O.; Azizi, H. Age-dependent root canal instrumentation techniques: A comprehensive narrative review. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2020, 45, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.J. Root canal treatment outcomes not affected by increasing age of patient. Evid. Based Dent. 2017, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigsten, E.; Kvist, T.; Jonasson, P.; EndoReCo; Davidson, T. Comparing Quality of Life of Patients Undergoing Root Canal Treatment or Tooth Extraction. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 19–28.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, I.; Bårdsen, A.; Haug, S.R. Impact of Case Difficulty, Endodontic Mishaps, and Instrumentation Method on Endodontic Treatment Outcome and Quality of Life: A Four-Year Follow-up Study. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.H.; Woronuk, J.I.; Tan, H.K.; Lenz, U.; Koch, R.; Boening, K.W.; Pinchbeck, Y.J. Oral health related quality of life and its association with sociodemographic and clinical findings in 3 northern outreach clinics. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 73, 153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamasha, A.A.; Hatiwsh, A. Quality of life and satisfaction of patients after nonsurgical primary root canal treatment provided by undergraduate students, graduate students and endodontic specialists. Int. Endod. J. 2013, 46, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, J.; Lorenzo, B.; Barrios, R.; Albaladejo, A.; Mirón Canelo, J.A.; López-Valverde, A. Patient-centered Outcomes of Root Canal Treatment: A Cohort Follow-up Study. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğramaci, E.J.; Rossi-Fedele, G. Patient-related outcomes and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelakantan, P.; Liu, P.; Dummer, P.M.; McGrath, C. Oral health–related quality of life (OHRQoL) before and after endodontic treatment: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo, M.O.; Ferreira, E.F.; Ribeiro Sobrinho, A.P.; Paiva, S.M.; Martins, R.C. Learning experience in endodontics: Brazilian students’ perceptions. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 77, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, T.; Sezgin, G.P.; SönmezKaplan, S. Dental students’ perception of difficulties concerning root canal therapy: A survey study. Saudi Endod. J. 2020, 10, 338. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.B.; Gufran, K.; Alhabib, O.; Alzahrani, F.; Abuelqomsan, M.S.; Karobari, M.I.; Alnajei, A.; Afroz, M.M.; Akram, S.M.; Heboyan, A. CBCT based study to analyze and classify root canal morphology of maxillary molars—A retrospective study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 6550–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, T.; Robb, N.; Love, R.M.; Amaral, R.R.; Rodrigues, V.P.; de Camargo, J.M.P.; Duarte, M.A.H. The impact of the use of magnifying dental loupes on the performance of undergraduate dental students undertaking simulated dental procedures. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Ghani, S.M.; Mohd Khairuddin, P.N.A.; Lim, T.W.; Md Sabri, B.A.; Abdul Hamid, N.F.; Baharuddin, I.H.; Schonwetter, D. Evaluation of dental students’ clinical communication skills from three perspective approaches: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2024, 28, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Freeman, R.; Hill, K.; Newton, T.; Humphris, G. Communication, Trust and Dental Anxiety: A Person-Centered Approach for Dental Attendance Behaviours. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindlisbacher, F.; Davis, J.M.; Ramseier, C.A. Dental students’ self-perceived communication skills for patient motivation. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2017, 21, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, S.; Schultz, J.H. A communication-focused curriculum for dental students–an experiential training approach. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; McClelland, A.; Bedi, R.; Furnham, A. The influence of practitioner nationality, experience, and sex in shaping patient preferences for dentists. Int. Dent. J. 2011, 61, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, A.J.; Mohamad, N.; Saddki, N.; Ahmad, W.M.A.W.; Alam, M.K. Patient satisfaction towards dentist-patient interaction among patients attending outpatient dental clinic hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clín. Integr. 2021, 21, e0123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Dundes, L. The implications of gender stereotypes for the dentist-patient relationship. J. Dent. Educ. 2008, 72, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Puerta, N.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. Pain and Avoidance during and after Endodontic Therapy: The Role of Pain Anticipation and Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umanah, A.; Osagbemiro, B.; Arigbede, A. Pattern of demand for endodontic treatment by adult patients in port-harcourt, South-South Nigeria. J. West. Afr. Coll. Surg. 2012, 2, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamedy, R.; Shakiba, B.; Fayazi, S.; Pak, J.G.; White, S.N. Patient-centered endodontic outcomes: A narrative review. Iran. Endod. J. 2013 8, 197–204.

- Franciscatto, G.J.; Brennan, D.S.; Gomes, M.S.; Rossi-Fedele, G. Association between pulp and periapical conditions and dental emergency visits involving pain relief: Epidemiological profile and risk indicators in private practice in Australia. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.M.; Huang, J.Y.; Yu, H.C.; Su, N.Y.; Chang, Y.C. Trends, demographics, and conditions of emergency dental visits in Taiwan 1997–2013: A nationwide population—Based retrospective study. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, M.T.P.; Abreu, L.C.; Martim, L.; Munchow, E.A.; Nagata, J.Y. Tooth and patient-Related Conditions May Influence Root Canal Treatment Indication. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 7973356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigsten, E.; Jonasson, P.; Kvist, T. Indications for root canal treatment in a Swedish county dental service: Patient- and tooth-specific characteristics. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasqualini, D.; Corbella, S.; Alovisi, M.; Taschieri, S.; Del Fabbro, M.; Migliaretti, G.; Carpegna, G.C.; Scotti, N.; Berutti, E. Postoperative quality of life following single-visit root canal treatment performed by rotary or reciprocating instrumentation: A randomized clinical trial. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorst, J.K.; Sfreddo, C.S.; de F Meira, G.; Zanatta, F.B.; Vettore, M.V.; Ardenghi, T.M. Socioeconomic status and oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2021, 49, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; McGrath, C.; Cheung, G.S. Quality of life and psychological well-being among endodontic patients: A case-control study. Aust. Dent. J. 2012, 57, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, F.A.; Matsuda, Y.; Natsir, N.; Kanno, T. Comparison of oral health-related quality of life among endodontic patients with irreversible pulpitis and pulp necrosis using the oral health-related endodontic patient’s quality of life scale. Odontology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.H.; Chang, J. Impact of endodontic case difficulty on operating time of single visit nonsurgical endodontic treatment under general anesthesia. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H.; Kretzler, B.; Zwar, L.; Lieske, B.; Seedorf, U.; Walther, C.; Aarabi, G. Does Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Differ by Income Group? Findings from a Nationally Representative Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, L.P.; Senna, M.I.B.; Alencar, G.P.; Rodrigues, L.G.; de Paula, J.S.; Ferreira, R.C. User satisfaction with public oral health services in the Brazilian Unified Health System. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarevich, A.; Pilotto, L.M.; Hilgert, J.B.; Celeste, R.K. User satisfaction with public and private dental services for different age groups in Brazil. Cadernos de saude publica. 2018, 34, e00110716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugas, N.N.; Lawrence, H.P.; Teplitsky, P.; Friedman, S. Quality of life and satisfaction outcomes of endodontic treatment. J. Endod. 2002, 28, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandraweera, L.; Goh, K.; Lai-Tong, J.; Newby, J.; Abbott, P. A survey of patients’ perceptions about, and their experiences of, root canal treatment. Aust. Endod. J. 2019, 45, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakershahrak, M.; Chrisopoulos, S.; Luzzi, L.; Jamieson, L.; Brennan, D. Income and Oral and General Health Related Quality of Life: The Modifying Effect of Sense of Coherence, Findings of a Cross Sectional Study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 2561–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vena, D.A.; Collie, D.; Wu, H.; Gibbs, J.L.; Broder, H.L.; Curro, F.A.; Thompson, V.P.; Craig, R.G.; PEARL Network Group. Prevalence of persistent pain 3-5 years post primary root canal therapy and its impact on oral health-related quality of life: PEARL networks findings. J Endod. 2014, 40, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, E.; Azabal, M.; Arias, A. Quality of Life and Satisfaction of Patients Two Years after Endodontic and Dental Implant Treatments Performed by Experienced Practitioners. J. Dent. 2022, 125, 104280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Difficulties | Division | Young (%) | Old (%) | p-Value | Male (%) | Female (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Easy | 33 (44) | 29 (38.7) | 0.533 ns | 49 (65.3) | 31 (41.3) | 0.009 * |

| Average | 36 (48) | 36 (48) | 25 (33.3) | 40 (53.3) | |||

| Difficult | 06 (8) | 10 (13.3) | 01 (1.3) | 04 (5.3) | |||

| Diagnosis | Easy | 29 (38.7) | 23 (30.7) | 0.462 ns | 40 (53.3) | 35 (46.7) | 0.113 ns |

| Average | 38 (50.7) | 40 (53.3) | 35 (46.7) | 36 (48) | |||

| Difficult | 08 (10.6) | 12 (16) | 0 (0) | 04 (5.3) | |||

| Rubber dam application | Easy | 19 (25.3) | 32 (42.7) | 0.077 ns | 42 (56) | 36 (48) | 0.389 ns |

| Average | 36 (48) | 29 (38.7) | 31 (41.3) | 34 (45.3) | |||

| Difficult | 20 (26.7) | 14 (18.6) | 02 (2.7) | 05 (6.7) | |||

| Access cavity preparation | Easy | 26 (34.7) | 25 (33.3) | 0.905 ns | 35 (46.7) | 31 (41.3) | 0.674 ns |

| Average | 38 (50.7) | 37 (49.3) | 33 (44) | 34 (45.3) | |||

| Difficult | 11 (14.7) | 13 (17.4) | 07 (9.3) | 10 (13.4) | |||

| Canal localization | Easy | 36 (48) | 18 (24) | <0.001 * | 34 (45.3) | 35 (46.7) | 0.899 ns |

| Average | 32 (42.7) | 30 (40) | 38 (50.7) | 36 (48) | |||

| Difficult | 07 (9.3) | 27 (36) | 03 (4) | 04 (5.3) | |||

| Working length establishment | Easy | 27 (36) | 25 (33.3) | 0.468 ns | 36 (48) | 31 (41.3) | 0.328 ns |

| Average | 38 (50.7) | 44 (58.7) | 38 (50.7) | 40 (53.4) | |||

| Difficult | 10 (13.3) | 06 (8) | 01 (1.3) | 04 (5.3) | |||

| Instrumentation | Easy | 26 (34.7) | 21 (28) | 0.4824 ns | 37 (49.3) | 31 (41.3) | 0.101 ns |

| Average | 38 (50.7) | 38 (50.7) | 38 (50.7) | 40 (53.4) | |||

| Difficult | 11 (14.7) | 16 (21.3) | 0 (0) | 04 (5.3) | |||

| Obturation | Easy | 23 (30.7) | 24 (32) | 0.944 ns | 39 (52) | 33 (44) | 0.558 ns |

| Average | 41 (54.7) | 39 (52) | 35 (46.7) | 40 (53.3) | |||

| Difficult | 11 (14.7) | 12 (16) | 01 (1.3) | 02 (2.7) |

| Dimension | Item | Never | Hardly Ever | Occasionally | Fairly Often | Very Often | Mean and SD | OHIP-14 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0; n (%) | >0; n (%) | ||||||||

| Functional limitation | Difficulty speaking | 432 (73.8) | 107 (18.3) | 24 (4.1) | 22 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0.535 ± 1.035 | 941 (80.42) | 229 (19.58) |

| Deterioration in the sense of taste | 509 (87.0) | 60 (10.3) | 16 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Physical pain | Painful burning sensation in the mouth | 485 (82.9) | 77 (13.2) | 15 (2.6) | 8 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.662 ± 1.156 | 919 (78.55) | 251 (21.45) |

| Discomfort when eating | 434 (74.2) | 76 (13.0) | 45 (7.7) | 30 (5.1) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Psychological discomfort | Lack of self-confidence | 495 (84.6) | 83 (14.2) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0.509 ± 0.914 | 915 (78.2) | 255 (21.8) |

| Feeling nervous | 420 (71.8) | 143 (24.4) | 15 (2.6) | 7 (1.2) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Physical disability | Dissatisfaction with your diet | 445 (76.1) | 117 (20.0) | 8 (1.4) | 15 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 0.692 ± 1.191 | 864 (73.84) | 306 (26.16) |

| Inability to complete meals | 419 (71.6) | 120 (20.5) | 31 (5.3) | 15 (2.6) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Psychological difficulty | Difficulty relaxing | 395 (67.5) | 122 (20.9) | 53 (9.0) | 15 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 0.621 ± 0.949 | 897 (76.67) | 273 (23.33) |

| Embarrassment | 502 (85.8) | 76 (13.0) | 7 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Social disability | Irritability | 447 (76.4) | 108 (18.5) | 23 (3.9) | 7 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0.571 ± 1.045 | 909 (77.69) | 261 (22.31) |

| Difficulty in functional performance | 462 (79) | 101 (17.3) | 8 (1.4) | 14 (2.4) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Handicap | Inability to live | 500 (85.5) | 71 (12.1) | 7 (1.2) | 7 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0.321 ± 0.872 | 1017 (86.92) | 153 (13.08) |

| Dissatisfaction with lifestyle | 517 (88.4) | 61 (10.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.2) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Total | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.91 ± 5.523 | 78.9% | 21.1% |

| Factors | Variable | n (%) 585 (100) | Gender | Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (%) 366 (62.56) | Females (%) 219 (37.44) | p-Value | Young (%) 385 (65.81) | Middle-Aged (%) 200 (34.19) | p-Value | |||

| Tooth type | Anterior | 70 (11.96) | 42 (11.47) | 28 (12.78) | 0.605 ns | 48 (12.46) | 22 (11) | 0.14 ns |

| Premolar | 118 (20.17) | 69 (18.85) | 49 (22.37) | 73 (18.96) | 45 (22.5) | |||

| Molar | 126 (21.53) | 76 (20.76) | 50 (22.83) | 83 (21.56) | 43 (21.5) | |||

| Anterior/Premolars | 99 (16.92) | 65 (17.76) | 34 (15.52) | 67 (17.40) | 32 (16) | |||

| Anterior/Molars | 68 (11.62) | 48 (13.11) | 20 (9.13) | 37 (9.61) | 31 (15.5) | |||

| Premolars/Molars | 104 (17.77) | 66 (18.03) | 38 (17.35) | 77 (20) | 27 (13.5) | |||

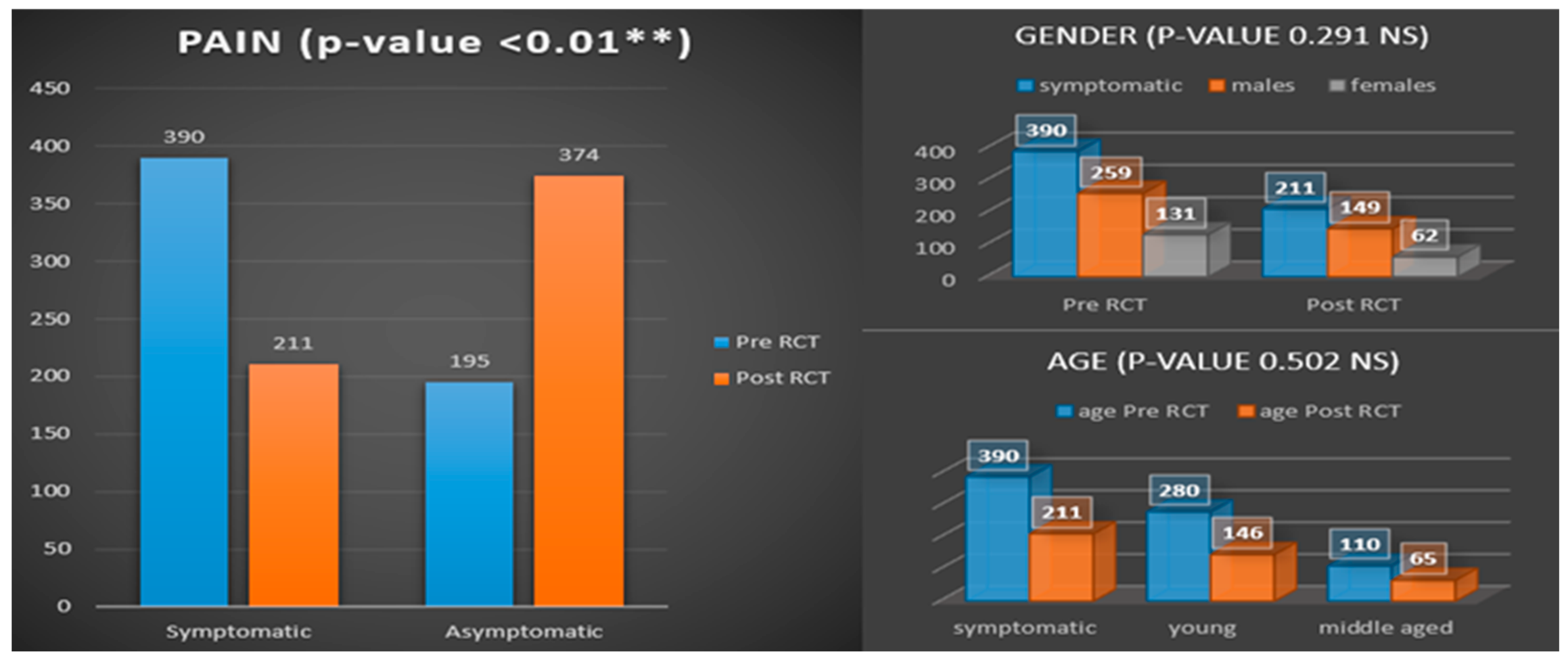

| Preoperative pain | Yes | 390 (66.66) | 259 (70.76) | 131 (59.81) | 0.007 * | 280 (72.73) | 110 (55) | <0.0001 * |

| No | 195 (33.33) | 107 (29.24) | 88 (40.19) | 105 (27.27) | 90 (45) | |||

| Postoperative pain | Yes | 211 (36.06) | 149 (40.71) | 62 (28.31) | 0.003 * | 146 (37.92) | 65 (32.5) | 0.195 ns |

| No | 374 (63.93) | 217 (59.29) | 157 (71.69) | 239 (62.08) | 135 (67.5) | |||

| Socioeconomic status | High income | 79 (13.50) | 46 (12.57) | 33 (15.07) | 0.47 ns | 53 (13.77) | 26 (13) | 0.946 ns |

| Middle income | 451 (77.09) | 282 (77.04) | 169 (77.17) | 296 (76.88) | 155 (77.5) | |||

| Low income | 55 (9.40) | 38 (10.39) | 17 (7.76) | 36 (9.35) | 19 (9.5) | |||

| Variables | Functional Limitation | Physical Pain | Psychological Discomfort | Physical Disability | Psychological Difficulty | Social Disability | Handicap | Total OHIP Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Young adults | 0.462 ± 0.932 | 0.649 ± 1.115 | 0.486 ± 0.905 | 0.686 ± 1.167 | 0.621 ± 0.947 | 0.571 ± 1.073 | 0.325 ± 0.893 | 3.8 ± 5.43 |

| Middle-aged adults | 0.675 ± 1.199 | 0.685 ± 1.234 | 0.555 ± 0.933 | 0.705 ± 1.239 | 0.62 ± 0.954 | 0.57 ± 0.99 | 0.315 ± 0.83 | 3.8 ± 5.43 | |

| p-value | 0.018 * | 0.724 ns | 0.385 ns | 0.853 ns | 0.0.992 ns | 0.987 ns | 0.899 ns | 0.500 ns | |

| Sex | Male | 0.574 ± 1.09 | 0.705 ± 1.207 | 0.516 ± 0.927 | 0.686 ± 1.226 | 0.623 ± 0.948 | 0.587 ± 1.071 | 0.328 ± 0.902 | 4.019 ± 5.735 |

| Female | 0.47 ± 0.935 | 0.589 ± 1.064 | 0.498 ± 0.895 | 0.703 ± 1.133 | 0.616 ± 0.952 | 0.543 ± 1.001 | 0.311 ± 0.821 | 3.731 ± 5.158 | |

| p-value | 0.242 ns | 0.241 ns | 0.811 ns | 0.863 ns | 0.936 ns | 0.622 ns | 0.816 ns | 0.541 ns | |

| Pain before RCT | Yes | 0.533 ± 1.01 | 0.695 ± 1.226 | 0.51 ± 0.869 | 0.7 ± 1.244 | 0.605 ± 0.947 | 0.546 ± 1.072 | 0.328 ± 0.949 | 3.918 ± 5.635 |

| No | 0.538 ± 1.085 | 0.595 ± 1.003 | 0.508 ± 1.002 | 0.677 ± 1.081 | 0.651 ± 0.953 | 0.621 ± 0.989 | 0.308 ± 0.694 | 3.897 ± 5.306 | |

| p-value | 0.955 ns | 0.324 ns | 0.975 ns | 0.825 ns | 0.580 ns | 0.417 ns | 0.789 ns | 0.966 ns | |

| Pain after RCT | Yes | 0.493 ± 0.953 | 0.588 ± 1.128 | 0.498 ± 0.886 | 0.654 ± 1.249 | 0.536 ± 0.962 | 0.507 ± 1.034 | 0.327 ± 0.906 | 3.602 ± 5.511 |

| No | 0.559 ± 1.079 | 0.703 ± 1.172 | 0.516 ± 0.931 | 0.714 ± 1.158 | 0.668 ± 0.939 | 0.607 ± 1.05 | 0.318 ± 0.853 | 4.086 ± 5.53 | |

| p-value | 0.460 ns | 0.265 ns | 0.815 ns | 0.560 ns | 0.104 ns | 0.265 ns | 0.906 ns | 0.310 ns | |

| Socioeconomic status | High income | 0.1899 ± 0.39471 | 0.6582 ± 1.0113 | 1 ± 1.79743 | 0.8481 ± 1.59397 | 0.6582 ± 1.22878 | 0.5443 ± 1.43042 | 0.2658 ± 0.85798 | 4.1646 ± 7.12603 |

| Middle income | 0.6608 ± 1.13636 | 0.6763 ± 1.22269 | 0.4678 ± 0.67046 | 0.7339 ± 1.15861 | 0.6563 ± 0.93063 | 0.6275 ± 1.01041 | 0.3525 ± 0.91523 | 4.1752 ± 5.43633 | |

| Low Income | 0 | 0.5455 ± 0.71539 | 0.1455 ± 0.35581 | 0.1273 ± 0.33635 | 0.2727 ± 0.44947 | 0.1455 ± 0.35581 | 0.1455 ± 0.35581 | 1.3818 ± 1.75848 | |

| p-value | <0.001 * | 0.731 ns | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.017 * | 0.005 * | 0.208 ns | 0.002 * | |

| Tooth Type | Anterior | 0.357 ± 0.835 | 0.357 ± 0.703 | 0.414 ± 0.648 | 0.471 ± 0.793 | 0.514 ± 0.775 | 0.386 ± 0.621 | 0.243 ± 0.55 | 2.743 ± 3.674 |

| Premolar | 0.627 ± 1.061 | 0.839 ± 1.377 | 0.559 ± 0.711 | 0.949 ± 1.395 | 0.78 ± 1.005 | 0.653 ± 1.033 | 0.424 ± 0.973 | 4.831 ± 5.771 | |

| Molar | 0.563 ± 1.121 | 0.778 ± 1.193 | 0.548 ± 1.078 | 0.738 ± 1.221 | 0.659 ± 1.013 | 0.69 ± 1.223 | 0.373 ± 0.994 | 4.349 ± 6.052 | |

| Anterior/Premolar | 0.444 ± 0.939 | 0.545 ± 0.895 | 0.455 ± 0.76 | 0.475 ± 0.849 | 0.525 ± 0.825 | 0.444 ± 0.906 | 0.303 ± 0.801 | 3.192 ± 4.688 | |

| Anterior/Molar | 0.603 ± 1.067 | 0.515 ± 0.889 | 0.426 ± 0.919 | 0.544 ± 1.028 | 0.441 ± 0.853 | 0.588 ± 1.068 | 0.279 ± 0.895 | 3.397 ± 5.417 | |

| Premolar/Molar | 0.558 ± 1.087 | 0.731 ± 1.395 | 0.577 ± 1.163 | 0.798 ± 1.43 | 0.673 ± 1.056 | 0.567 ± 1.147 | 0.24 ± 0.818 | 4.144 ± 6.228 | |

| p-value | 0.523 ns | 0.044 * | 0.73 ns | 0.021 * | 0.148 ns | 0.303 ns | 0.589 ns | 0.085 ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirza, M.B.; Almuteb, A.B.; Alsheddi, A.T.; Hashem, Q.; Abuelqomsan, M.A.; AlMokhatieb, A.; AlBader, S.; AlShehri, A. Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Challenges Faced by Undergraduate Dental Students During Root Canal Treatment (RCT) and the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients After RCT. Medicina 2025, 61, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020215

Mirza MB, Almuteb AB, Alsheddi AT, Hashem Q, Abuelqomsan MA, AlMokhatieb A, AlBader S, AlShehri A. Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Challenges Faced by Undergraduate Dental Students During Root Canal Treatment (RCT) and the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients After RCT. Medicina. 2025; 61(2):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020215

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirza, Mubashir Baig, Abdullah Bajran Almuteb, Abdulaziz Tariq Alsheddi, Qamar Hashem, Mohammed Ali Abuelqomsan, Ahmed AlMokhatieb, Shahad AlBader, and Abdullah AlShehri. 2025. "Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Challenges Faced by Undergraduate Dental Students During Root Canal Treatment (RCT) and the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients After RCT" Medicina 61, no. 2: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020215

APA StyleMirza, M. B., Almuteb, A. B., Alsheddi, A. T., Hashem, Q., Abuelqomsan, M. A., AlMokhatieb, A., AlBader, S., & AlShehri, A. (2025). Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Challenges Faced by Undergraduate Dental Students During Root Canal Treatment (RCT) and the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients After RCT. Medicina, 61(2), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020215