Clinical Analysis of Congenital Duodenal Obstruction and the Role of Annular Pancreas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Surveillance and Definitions

2.3. Genetic Assessment

2.4. Confirmation of CDO and Assignments of Groups

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bethell, G.S.; Long, A.-M.; Knight, M.; Hall, N.J. Congenital duodenal obstruction in the UK: A population-based study. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020, 105, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schima, W.; Ba-Ssalamah, A.; Plank, C.; Kulinna-Cosentini, C.; Püspök, A. Pancreas. Congenital changes, acute and chronic pancreatitis: Angeborene Veränderungen, akute und chronische Pankreatitis. Radiologe 2007, 47, S41–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamisawa, T.; Yuyang, T.; Egawa, N.; Ishiwata, J.-i.; Okamoto, A. A new embryologic hypothesis of annular pancreas. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2001, 48, 277–278. [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee, D.C. Laparoscopic repair of duodenal atresia: Revisited. World J. Surg. 2011, 35, 1781–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riall, T. Pancreas anatomy and physiology. Greenfield’s Surg./Sci. Princ. Pract. 2011, 51, 802–803. [Google Scholar]

- Rinnab, L.; Schulz, K.; Siech, M. A rare localization of annular pancreas at the pars horizontalis duodeni—Case report. Zentralblatt Chir. 2004, 129, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, G.I.; Topazian, M.D.; Gleeson, F.C.; Levy, M.J. EUS features of annular pancreas (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2007, 65, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, S.B. Sonography of pancreatic ductal anatomic characteristics in annular pancreas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2002, 21, 1315–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijpers, A.G.; Eeftinck Schattenkerk, L.D.; Straver, B.; Zwijnenburg, P.J.; Broers, C.J.; Van Heurn, E.L.; Gorter, R.R.; Derikx, J.P.M. The Incidence of Associated Anomalies in Children with Congenital Duodenal Obstruction—A Retrospective Cohort Study of 112 Patients. Children 2022, 9, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Liu, X.; Lu, Y.; Wu, B.; Liu, R.; Liu, B.; Yan, K.; Chen, H.; Cheng, G.; Wang, L.; et al. Overdosage of HNF1B gene associated with annular pancreas detected in neonate patients with 17q12 duplication. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 615072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.; Rocha, G.; Soares, P.; Morgado, H.; Baptista, M.J.; Azevedo, I.; Fernandes, S.; Brandão, O.; Sen, P.; Guimarães, H. A novel mutation in FOXF1 gene associated with alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins, intestinal malrotation and annular pancreas. Neonatology 2013, 103, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankovcik, R.; Jirasek, J.E.; Kucera, E.; Feyereisl, J.; Radonak, J.; Dudas, M. Prenatal diagnosis of annular pancreas: Reliability of the double bubble sign with periduodenal hyperechogenic band. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2009, 24, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoamin, H.H.A.; Kadhem, S.H.; Saleh, A.M. Annular pancreas in neonates; case series and review of literatures. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2022, 19, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engwall-Gill, A.J.; Zhou, A.L.; Penikis, A.B.; Sferra, S.R.; Jelin, A.C.; Blakemore, K.J.; Kunisaki, S.M. Prenatal sonography in suspected proximal gastrointestinal obstructions: Diagnostic accuracy and neonatal outcomes. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 58, 1090–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Tong, L.; Ma, M.; Tan, X.; Luo, G.; Fei, Z.; Nie, D. The application of prenatal ultrasound in the diagnosis of congenital duodenal obstruction. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.; Pang, H.; Yang, H.; Luo, H. Evaluation of prenatal and postnatal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of fetal double bubble sign. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2024, 14, 6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, W.-b.; Wang, S.-q.; Wang, Y.-b. Laparoscopic diagnosis and treatment of neonates with duodenal obstruction associated with an annular pancreas: Report of 11 cases. Surg. Today 2015, 45, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Kang, Q.; Shi, S.; Hu, W. Annular pancreas in China: 9 years’ experience from a single center. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigiter, M.; Yildiz, A.; Firinci, B.; Yalcin, O.; Oral, A.; Salman, A.B. Annular pancreas in children: A decade of experience. Eurasian J. Med. 2010, 42, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşdemir, Ü.; Eyisoy, Ö.G.; Gezer, M.; Celayir, A.; Özdemir, M.E.; Demirci, O. Prenatal-Postnatal Outcomes and Prognostic Risk Factors of Fetal Volvulus: Analysis of 26 Cases. Prenat. Diagn. 2024, 45, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, O.; Eriç Özdemir, M.; Kumru, P.; Celayir, A. Clinical significance of prenatal double bubble sign on perinatal outcome and literature review. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, J.C.; McCormick, B.; Johnson, C.T.; Miller, J.; Jelin, E.; Blakemore, K.; Jelin, A.C. The double bubble sign: Duodenal atresia and associated genetic etiologies. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2020, 47, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Zhou, H.; Fu, F.; Li, R.; Lei, T.; Li, Y.; Cheng, K.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, L.; et al. Prenatal diagnosis of Williams-Beuren syndrome by ultrasound and chromosomal microarray analysis. Mol. Cytogenet. 2022, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Prenatal Diagnosis | n (%) |

| Duodenal obstruction | 34 (100) |

| Chromosomal abnormalities | 19 (55.9) |

| Perinatal outcomes | |

| Termination | 3 (8.8) |

| Intrauterine demise | 1 (2.9) |

| Live birth | 30 (88.2) |

| Ethiology of duodenal obstruction in live births | |

| Duodenal atresia | 15 (50) |

| Duodenal web | 2 (6.6) |

| Annular pancreas | 13 (43.3) |

| CDO with Annular Pancreas (n = 13) | CDO Without Annular Pancreas (n = 17) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age, years (median/range) | 34 (22–42) | 33 (23–42) | 0.509 |

| Parity (median/range) | 3 (1–9) | 3 (1–5) | 0.837 |

| Consanguineous marriage (n, %) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (23.5) | |

| GA at prenatal diagnosis, weeks (median/range) | 29 (22–37) | 28 (24–33) | 0.432 |

| Mode of delivery | 0.407 | ||

| Vaginal (n, %) | 2 (15.4) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Cesarean (n, %) | 11 (84.6) | 11 (64.7) | |

| GA at delivery, weeks (median/range) | 35 (33–40) | 37 (27–41) | 0.213 |

| Fetal–neonatal characteristics | |||

| Gender | 0.259 | ||

| Male (n, %) | 3 (23) | 8 (47) | |

| Female (n, %) | 10 (77) | 9 (53) | |

| Genetic result | |||

| Normal (n, %) | 3 (23) | 11 (64.7) | |

| Trisomy 21 (n, %) | 7 (53.8) | 6 (35.3) | |

| 7q11.23 deletion (Williams–Beuren) (n, %) | 1 (7.7) | - | |

| 46,XX,(der 21) (n, %) | 1 (7.7) | - | |

| 47,XX,inv(9)(p11q13),+21 (n, %) | 1 (7.7) | - | |

| Chromosomal abnormality (n, %) | 10 (77) | 6 (35.3) | 0.033 |

| Ultrasonographic features | |||

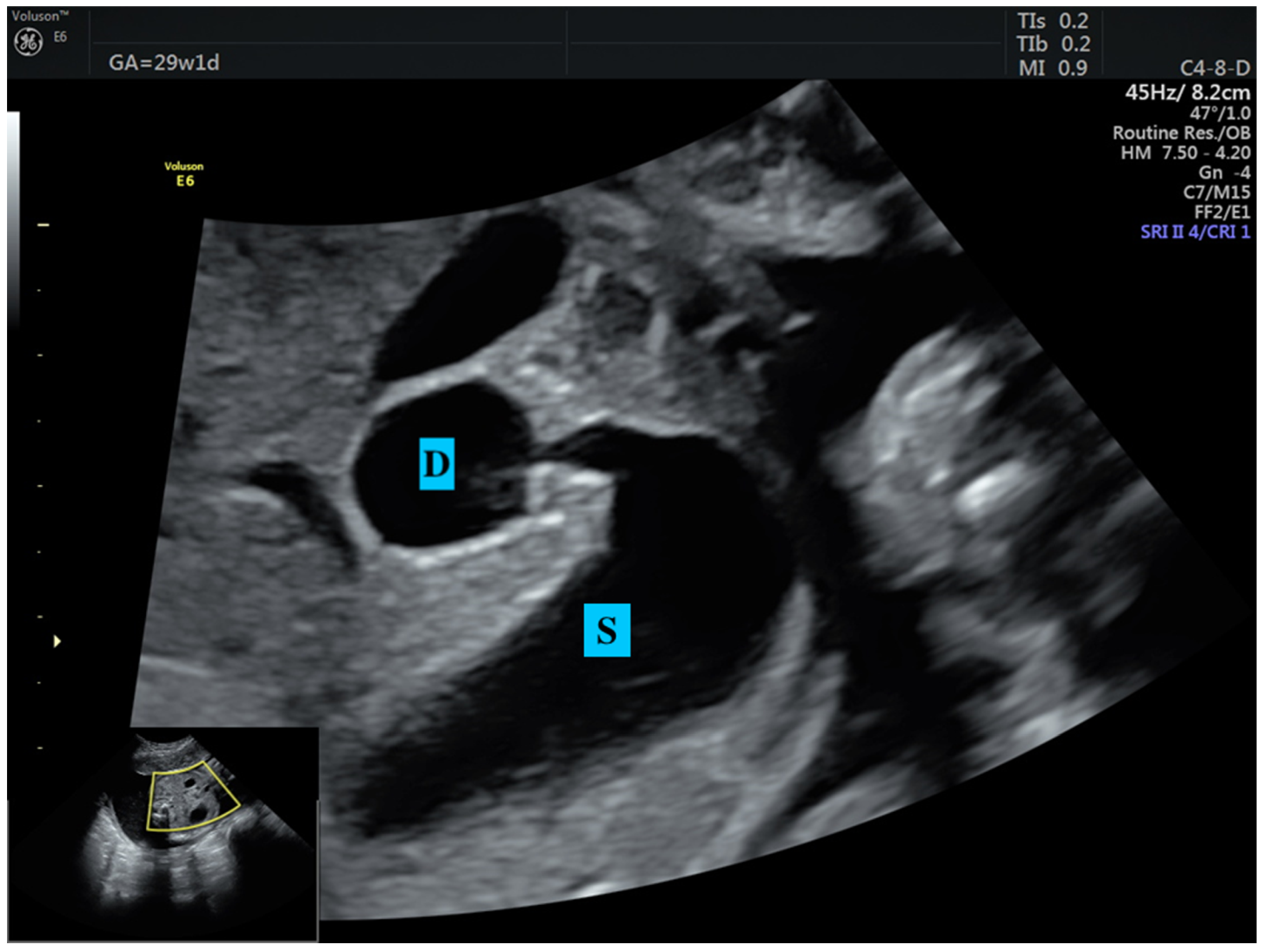

| Double bubble sign (n, %) | 13 (100) | 17 (100) | N/A |

| Dilated stomach (n, %) | 13 (100) | 17 (100) | N/A |

| FGR (n, %) | 6 (46.2) | 5 (29.4) | 0.454 |

| Early onset (n, %) | 4 (30.7) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Late onset (n, %) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Polyhydramnios (n, %) | 12 (92.3) | 17 (100) | 0.433 |

| Associated anomaly (n, %) | 4 (30.8) | 2 (11.8) | 0.204 |

| Cardiac anomaly (n, %) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Umbilical–systemic shunt (n, %) | 1 (7.7) | - | |

| Esophageal atresia (n, %) | - | 1 (5.9) | |

| Birthweight, grams (mean ± SD) | 2167 ± 145 | 2466 ± 167 | 0.205 |

| Delivery to surgery, days (median/range) | 2 (0–10) | 3 (0–16) | 0.363 |

| Hospital stay after surgery, days (median/range) | 19 (10–68) | 23 (15–90) | 0.152 |

| Current status in long term | 0.443 | ||

| Death (n, %) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Living (n, %) | 8 (61.5) | 13 (76.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taşdemir, Ü.; Demirci, O. Clinical Analysis of Congenital Duodenal Obstruction and the Role of Annular Pancreas. Medicina 2025, 61, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020171

Taşdemir Ü, Demirci O. Clinical Analysis of Congenital Duodenal Obstruction and the Role of Annular Pancreas. Medicina. 2025; 61(2):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020171

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaşdemir, Ümit, and Oya Demirci. 2025. "Clinical Analysis of Congenital Duodenal Obstruction and the Role of Annular Pancreas" Medicina 61, no. 2: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020171

APA StyleTaşdemir, Ü., & Demirci, O. (2025). Clinical Analysis of Congenital Duodenal Obstruction and the Role of Annular Pancreas. Medicina, 61(2), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020171