Infantile Spasms (West Syndrome): Integrating Genetic, Neurotrophic, and Hormonal Mechanisms Toward Precision Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

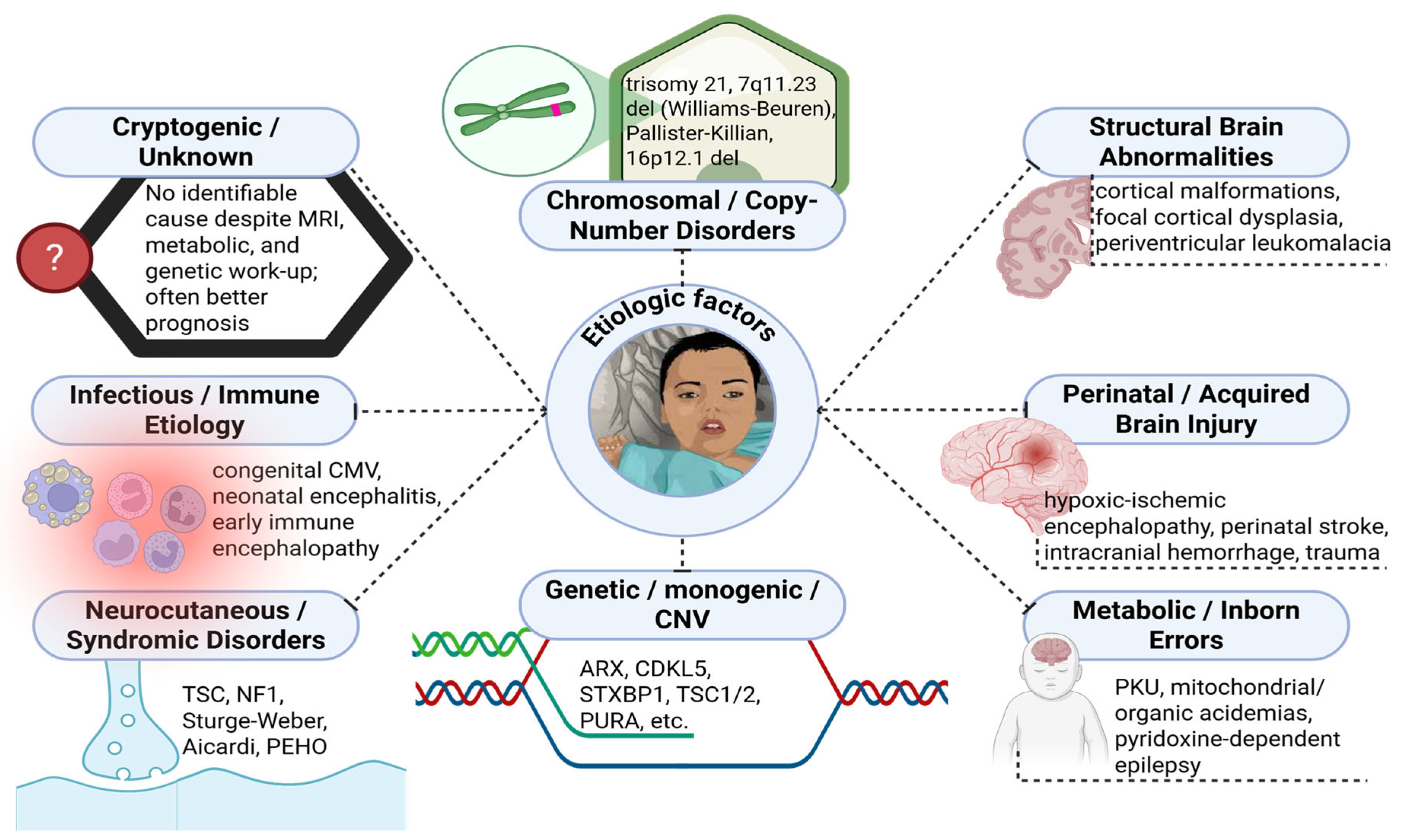

3. Multifactorial Etiology

3.1. Genetic and Molecular Determinants

3.2. Other Factors

4. Pathogenesis and Molecular Mechanisms

4.1. Network-Level Pathophysiology: Disrupted Cortical–Subcortical Circuits

4.2. Neurotrophin Dysregulation (BDNF, NGF, GDNF): Dual Role in Injury and Epileptogenesis

4.3. IGF-1 Deficiency and Impaired Steroid-Driven Trophic Signaling

4.4. GABAergic Immaturity and Neurosteroid Deficiency

4.5. Immune Activation, Inflammation, and mTOR Pathway in IS Epileptogenesis

5. Therapeutic Approaches

6. Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACADS | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, C-2 to C-3 short chain |

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| AD | Autosomal dominant |

| AAN | American Academy of Neurology |

| AASA | α-Aminoadipic semialdehyde |

| ALG13 | Asparagine-linked glycosylation 13 |

| ARX | Aristaless related homeobox |

| ATP2A2 | ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 |

| B3GALNT2 | Beta-1,3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2 |

| CAGSSS | Cataract–ataxia–short stature–skeletal dysplasia–seizures syndrome |

| CDKL5 | Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 |

| CNV | Copy number variation |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DCX | Doublecortin |

| DEE | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| FOXG1 | Forkhead box G1 |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GDNF | Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| GRIN2A | Glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2A |

| GRIN2B | Glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2B |

| IESS | Infantile epileptic spasms syndrome |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| ILAE | International League Against Epilepsy |

| ISs | Infantile spasms |

| KCNQ2 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 2 |

| LIS1 | Platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase 1B subunit 1 (lissencephaly 1) |

| MAGI2 | Membrane associated guanylate kinase inverted 2 |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NF1 | Neurofibromin 1 |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| NSD1 | Nuclear receptor-binding SET domain protein 1 |

| PKU | Phenylketonuria |

| PNPO | Pyridox(am)ine 5′-phosphate oxidase |

| RARS2 | Arginyl-tRNA synthetase 2 (mitochondrial) |

| RYR1 | Ryanodine receptor 1 (skeletal muscle) |

| RYR2 | Ryanodine receptor 2 (cardiac) |

| RYR3 | Ryanodine receptor 3 (neuronal) |

| SCN1A | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 |

| SCN2A | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 2 |

| SCN8A | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 8 |

| STXBP1 | Syntaxin-binding protein 1 |

| TSC | Tuberous sclerosis complex |

| TSC1 | Tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (hamartin) |

| TSC2 | Tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (tuberin) |

| VGB | Vigabatrin |

| WDR45 | WD repeat domain phosphoinositide-interacting protein 45 |

| WES | Whole-exome sequencing |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| WS | West syndrome |

| WWOX | WW domain-containing oxidoreductase |

| ZNHIT3 | Zinc finger HIT-type containing 3 |

| UKISS | United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study |

References

- Zuberi, S.M.; Wirrell, E.C.; Yozawitz, E.; Wilmshurst, J.M.; Specchio, N.; Riney, K.; Pressler, R.; Auvin, S.; Samia, P.; Hirsch, E.; et al. ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Neonates and Infants: Position Statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1349–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, J.D.; Elliott, K.S.; Shetty, J.; Armstrong, M.; Brunklaus, A.; Cutcutache, I.; A Diver, L.; Dorris, L.; Gardiner, S.; Jollands, A.; et al. Early Childhood Epilepsies: Epidemiology, Classification, Aetiology, and Socio-Economic Determinants. Brain 2021, 144, 2879–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Y.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Q.-H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Zhang, B.; Zou, L.-P. Diagnostic Yield of a Multi-Strategy Genetic Testing Procedure in a Nationwide Cohort of 728 Patients with Infantile Spasms in China. Seizure 2022, 103, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilcott, E.; Díaz, J.A.; Bertram, C.; Berti, M.; Karda, R. Genetic Therapeutic Advancements for Dravet Syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2022, 132, 108741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.K.; Chakrabarty, B. Treatment of West Syndrome: From Clinical Efficacy to Cost-Effectiveness, the Juggernaut Rolls On. Indian J. Pediatr. 2022, 89, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.E.; Jain, P.; RamachandranNair, R.; Jones, K.C.; Whitney, R. Genetic Advancements in Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome and Opportunities for Precision Medicine. Genes 2024, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poke, G.; Stanley, J.; Scheffer, I.E.; Sadleir, L.G. Epidemiology of Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy and of Intellectual Disability and Epilepsy in Children. Neurology 2023, 100, e1363–e1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, E.M.P.; Wyllie, E. West Syndrome and the New Classification of Epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Y.; Ikeda, A.; Naruto, T.; Kurosawa, K. Early-Onset West Syndrome with Developmental Delay Associated with a Novel KLHL20 Variant. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2024, 194, e63600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, E.H.; Silva, A.M.P.D.; Santos, K.D.A.D.; Neto, A.P.M.; Koppanatham, A.; Souza, J.C.A.M.; Pacheco-Barrios, N.; Rocha, G.S.; Noleto, G.S. Corticotherapy versus Adrenocorticotropic Hormone for Treating West Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2025, 83, s00451811173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahan, S.; Sahu, J.K.; Madaan, P.; Suthar, R.; Pattanaik, S.; Saini, A.G.; Saini, L.; Kumar, A.; Sankhyan, N. Effectiveness and Safety of Nitrazepam in Children with Resistant West Syndrome. Indian J. Pediatr. 2022, 89, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Shen, X.-R.; Fang, Z.-B.; Jiang, Z.-Z.; Wei, X.-J.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Yu, X.-F. Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies and Neurogenetic Diseases. Life 2021, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyanova, M.; Yahya, D.; Hachmeriyan, M.; Levkova, M. Diagnostic Yield of Next-Generation Sequencing for Rare Pediatric Genetic Disorders: A Single-Center Experience. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinkšel, M.; Writzl, K.; Maver, A.; Peterlin, B. Improving Diagnostics of Rare Genetic Diseases with NGS Approaches. J. Community Genet. 2021, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Roberts, R.; Tong, W. Toward Clinical Implementation of Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Genetic Testing in Rare Diseases: Where Are We? Trends Genet. 2019, 35, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Marmiesse, A.; Gouveia, S.; Couce, M.L. NGS Technologies as a Turning Point in Rare Disease Research, Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 404–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.B.; Buckingham, K.J.; Lee, C.; Bigham, A.W.; Tabor, H.K.; Dent, K.M.; Huff, C.D.; Shannon, P.T.; Jabs, E.W.; Nickerson, D.A. Exome Sequencing Identifies the Cause of a Mendelian Disorder. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.; Choi, M. Application of Whole-Exome Sequencing to Identify Disease-Causing Variants in Inherited Human Diseases. Genom. Inform. 2012, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazi, S.; Dadzadi, M.; Darvazi, M.; Seddigh, N.; Allahverdi, A. Protein Modification in Neurodegenerative Diseases. MedComm 2024, 5, e674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, A.; Di Scipio, M.; Grewal, S.; Suk, Y.; Trinari, E.; Ejaz, R.; Whitney, R. The Genetics of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex and Related mTORopathies: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Genes 2024, 15, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR at the Nexus of Nutrition, Growth, Ageing and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boff, M.O.; Xavier, F.A.C.; Diz, F.M.; Gonçalves, J.B.; Ferreira, L.M.; Zambeli, J.; Pazzin, D.B.; Previato, T.T.R.; Erwig, H.S.; Gonçalves, J.I.B.; et al. mTORopathies in Epilepsy and Neurodevelopmental Disorders: The Future of Therapeutics and the Role of Gene Editing. Cells 2025, 14, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surdi, P.; Trivisano, M.; De Dominicis, A.; Mercier, M.; Piscitello, L.M.; Pavia, G.C.; Calabrese, C.; Cappelletti, S.; Correale, C.; Mazzone, L.; et al. Unveiling the Disease Progression in Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathies: Insights from EEG and Neuropsychology. Epilepsia 2024, 65, 3279–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellock, J.M.; Hrachovy, R.; Shinnar, S.; Baram, T.Z.; Bettis, D.; Dlugos, D.J.; Gaillard, W.D.; Gibson, P.A.; Holmes, G.L.; Nordli, D.R.; et al. Infantile Spasms: A U.S. Consensus Report. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 2175–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, E.; Go, C.; McCoy, B.; Snead, O.C. Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Infantile Spasms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Epilepsy Res. 2015, 109, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J.D., Jr.; Hrachovy, R.A. Pathogenesis of Infantile Spasms: A Model Based on Developmental Desynchronization. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2005, 22, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanopoulou, A.S.; Moshé, S.L. Pathogenesis and New Candidate Treatments for Infantile Spasms and Early Life Epileptic Encephalopathies: A View from Preclinical Studies. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 79, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirrell, E.C.; Shellhaas, R.A.; Joshi, C.; Keator, C.; Kumar, S.; Mitchell, W.G. How Should Children with West Syndrome Be Efficiently and Accurately Investigated? Results from the National Infantile Spasms Consortium. Epilepsia 2015, 56, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, I.E.; French, J.; Hirsch, E.; Jain, S.; Mathern, G.W.; Moshé, S.L.; Perucca, E.; Tomson, T.; Wiebe, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Classification of the Epilepsies: New Concepts for Discussion and Debate—Special Report of the ILAE Classification Task Force of the Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia Open 2016, 1, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euro E-RESC; Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project; Epi4K Consortium. De Novo Mutations in Synaptic Transmission Genes Including DNM1 Cause Epileptic Encephalopathies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 95, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C.A.; Nabbout, R.; Galanopoulou, A.S. Mechanisms of Epileptogenesis in Pediatric Epileptic Syndromes: Rasmussen Encephalitis, Infantile Spasms, and Febrile Infection-Related Epilepsy Syndrome (FIRES). Neurotherapeutics 2014, 11, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, A.; Bayat, M.; Rubboli, G.; Møller, R.S. Epilepsy Syndromes in the First Year of Life and Usefulness of Genetic Testing for Precision Therapy. Genes 2021, 12, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epi4K Consortium; Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project. De Novo Mutations in Epileptic Encephalopathies. Nature 2013, 501, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Jaenisch, R.; Sur, M. The Role of GABAergic Signalling in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, J.K.; Madaan, P.; Prakash, K. The Landscape of Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome in South Asia: Peculiarities, Challenges, and Way Forward. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 2023, 12, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Liao, J.; Zhao, C. Microstructural Injury to the Optic Nerve with Vigabatrin Treatment in West Syndrome: A DTI Study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, L.P.B.; Henriques-Souza, A.M.M.; Silveira, M.R.M.D.; Seguti, L.; Santos, M.L.S.F.; Montenegro, M.A.; Antoniuk, S.; Manreza, M.L.G. Brazilian Experts’ Consensus on the Treatment of Infantile Epileptic Spasm Syndrome in Infants. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2023, 81, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalinia, M.; Weiskirchen, R. Advances in Personalized Medicine: Translating Genomic Insights into Targeted Therapies for Cancer Treatment. Ann. Transl. Med. 2025, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, D.A.; Sadhwani, A.; Byars, A.W.; de Vries, P.J.; Franz, D.N.; Whittemore, V.H.; Filip-Dhima, R.; Murray, D.; Kapur, K.; Sahin, M. Everolimus for Treatment of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex-Associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2017, 4, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, G.K.; Palliser, H.K.; Shaw, J.C.; Hodgson, D.M.; Walker, D.W.; Hirst, J.J. Neurosteroid-Based Intervention Using Ganaxolone and Emapunil for Improving Stress-Induced Myelination Deficits and Neurobehavioural Disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 133, 105423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, J.K.; Helbig, I.; Metcalf, C.S.; Lubbers, L.S.; Isom, L.L.; Demarest, S.; Goldberg, E.M.; George, A.L., Jr.; Lerche, H.; Weckhuysen, S.; et al. Precision Medicine for Genetic Epilepsy on the Horizon: Recent Advances, Present Challenges, and Suggestions for Continued Progress. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 2461–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striano, P.; Minassian, B.A. From Genetic Testing to Precision Medicine in Epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snead, O.C. How Does ACTH Work Against Infantile Spasms? Bedside to Bench. Ann. Neurol. 2001, 49, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baram, T.Z.; Mitchell, W.G.; Tournay, A.; Snead, O.C.; Hanson, R.A.; Horton, E.J. High-Dose Corticotropin (ACTH) versus Prednisone for Infantile Spasms: A Prospective, Randomized, Blinded Study. Pediatrics 1996, 97, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrachovy, R.A.; Frost, J.D.; Kellaway, P.; Zion, T.E. Double-Blind Study of ACTH vs. Prednisone Therapy in Infantile Spasms. J. Pediatr. 1983, 103, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram, T.Z. What Are the Reasons for the Strikingly Different Approaches to the Use of ACTH in Infants with West Syndrome? Brain Dev. 2001, 23, 647–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgeman, R.M.; Kapur, K.; Paris, A.; Marti, C.; Can, A.; Kimia, A.; Loddenkemper, T.; Bergin, A.; Poduri, A.; Libenson, M.; et al. Effectiveness of Once-Daily High-Dose ACTH for Infantile Spasms. Epilepsy Behav. 2016, 59, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, C.Y.; Mackay, M.T.; Weiss, S.K.; Stephens, D.; Adams-Webber, T.; Ashwal, S.; Snead, O.C.; Child Neurology Society; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-Based Guideline Update: Medical Treatment of Infantile Spasms. Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 2012, 78, 1974–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, M.T.; Weiss, S.K.; Adams-Webber, T.; Ashwal, S.; Stephens, D.; Ballaban-Gill, K.; Baram, T.Z.; Duchowny, M.; Hirtz, D.; Pellock, J.M.; et al. Practice Parameter: Medical Treatment of Infantile Spasms. Report of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 2004, 62, 1668–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroff, O.A.; Rothman, D.L.; Behar, K.L.; Collins, T.L.; Mattson, R.H. Human Brain GABA Levels Rise Rapidly after Initiation of Vigabatrin Therapy. Neurology 1996, 47, 1567–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, F.J.; Edwards, S.W.; Alber, F.D.; Hancock, E.; Johnson, A.L.; Kennedy, C.R.; Likeman, M.; Lux, A.L.; Mackay, M.; Mallick, A.A.; et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Hormonal Treatment versus Hormonal Treatment with Vigabatrin for Infantile Spasms (ICISS): A Randomised, Multicentre, Open-Label Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffer, I.E.; Berkovic, S.; Capovilla, G.; Connolly, M.B.; French, J.; Guilhoto, L.; Hirsch, E.; Jain, S.; Mathern, G.W.; Moshé, S.L.; et al. ILAE Classification of the Epilepsies: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuskaitis, C.J.; Ruzhnikov, M.R.Z.; Howell, K.B.; Allen, I.E.; Kapur, K.; Dlugos, D.J.; Scheffer, I.E.; Poduri, A.; Sherr, E.H. Infantile Spasms of Unknown Cause: Predictors of Outcome and Genotype–Phenotype Correlation. Pediatr. Neurol. 2018, 87, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheless, J.W.; Gibson, P.A.; Rosbeck, K.L.; Hardin, M.; O’Dell, C.; Whittemore, V.; Pellock, J.M. Infantile Spasms (West Syndrome): Update and Resources for Pediatricians and Providers to Share with Parents. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, A.L.; Osborne, J.P. A Proposal for Case Definitions and Outcome Measures in Studies of Infantile Spasms and West Syndrome: Consensus Statement of the West Delphi Group. Epilepsia 2004, 45, 1416–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K. West Syndrome: Etiological and Prognostic Aspects. Brain Dev. 1998, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J.P.; Lux, A.L.; Edwards, S.W.; Hancock, E.; Johnson, A.L.; Kennedy, C.R.; Newton, R.W.; Verity, C.M.; O’Callaghan, F.J. The Underlying Etiology of Infantile Spasms (West Syndrome): Information from the United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study (UKISS) on Contemporary Causes and Their Classification. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 2168–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtahara, S.; Ohtsuka, Y.; Yamatogi, Y.; Oka, E.; Yoshinaga, H.; Sato, M. Prenatal Etiologies of West Syndrome. Epilepsia 1993, 34, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.R.; Young, E.J.; Pani, A.M.; Freckmann, M.L.; Lacassie, Y.; Howald, C.; Fitzgerald, K.K.; Peippo, M.; Morris, C.A.; Shane, K.; et al. Infantile Spasms Is Associated with Deletion of the MAGI2 Gene on Chromosome 7q11.23–q21.11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 83, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, M.; Oguni, H.; Liang, J.S.; Ikeda, H.; Imai, K.; Hirasawa, K.; Imai, K.; Tachikawa, E.; Shimojima, K.; Osawa, M.; et al. STXBP1 Mutations Cause Not Only Ohtahara Syndrome but Also West Syndrome: Result of a Japanese Cohort Study. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 2449–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striano, P.; Paravidino, R.; Sicca, F.; Chiurazzi, P.; Gimelli, S.; Coppola, A.; Robbiano, A.; Traverso, M.; Pintaudi, M.; Giovannini, S.; et al. West Syndrome Associated with 14q12 Duplications Harboring FOXG1. Neurology 2011, 76, 1600–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, J.L.; Lachance, M.; Hamdan, F.F.; Carmant, L.; Lortie, A.; Diadori, P.; Major, P.; Meijer, I.A.; Lemyre, E.; Cossette, P.; et al. The Genetic Landscape of Infantile Spasms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 4846–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhongshu, Z.; Weiming, Y.; Yukio, F.; Cheng-Ning, Z.; Zhixing, W. Clinical Analysis of West Syndrome Associated with Phenylketonuria. Brain Dev. 2001, 23, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riikonen, R. Infantile Spasms: Infectious Disorders. Neuropediatrics 1993, 24, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenheim, M.A.; Frost, J.D.; Hrachovy, R.A. Time Interval from a Brain Insult to the Onset of Infantile Spasms. Pediatr. Neurol. 2008, 38, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavone, P.; Striano, P.; Falsaperla, R.; Pavone, L.; Ruggieri, M. Infantile Spasms Syndrome, West Syndrome and Related Phenotypes: What We Know in 2013. Brain Dev. 2014, 36, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciorkowski, A.R.; Thio, L.L.; Dobyns, W.B. Genetic and Biologic Classification of Infantile Spasms. Pediatr. Neurol. 2011, 45, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachua, T.; Di Grazia, P.; Chern, C.R.; Johnkutty, M.; Hellman, B.; Lau, H.A.; Shakil, F.; Daniel, M.; Goletiani, C.; Velíšková, J.; et al. Estradiol Does Not Affect Spasms in the Betamethasone-NMDA Rat Model of Infantile Spasms. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeta, L.; Malacarne, M.; Padula, A.; Drongitis, D.; Verrillo, L.; Lioi, M.B.; Chiariello, A.M.; Bianco, S.; Nicodemi, M.; Piccione, M.; et al. Further Delineation of Duplications of ARX Locus Detected in Male Patients with Varying Degrees of Intellectual Disability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, A.; Sinibaldi, L.; Genovese, S.; Catino, G.; Mei, V.; Pompili, D.; Sallicandro, E.; Falasca, R.; Liambo, M.T.; Faggiano, M.V.; et al. A Case of CDKL5 Deficiency Due to an X Chromosome Pericentric Inversion: Delineation of Structural Rearrangements as an Overlooked Recurrent Pathological Mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bennison, S.A.; Robinson, L.; Toyo-Oka, K. Responsible Genes for Neuronal Migration in the Chromosome 17p13.3: Beyond Pafah1b1 (Lis1), Crk and Ywhae (14-3-3ε). Brain Sci. 2021, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.M.; Gleeson, J.G.; Shoup, S.M.; Walsh, C.A. A YAC Contig in Xq22.3–q23, from DXS287 to DXS8088, Spanning the Brain-Specific Genes Doublecortin (DCX) and PAK3. Genomics 1998, 52, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecourtois, M.; Poirier, K.; Friocourt, G.; Jaglin, X.; Goldenberg, A.; Saugier-Veber, P.; Chelly, J.; Laquerrière, A. Human Lissencephaly with Cerebellar Hypoplasia Due to Mutations in TUBA1A: Expansion of the Foetal Neuropathological Phenotype. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, I.M.; Yatsenko, S.A.; Hixson, P.; Reimschisel, T.; Thomas, M.; Wilson, W.; Dayal, U.; Wheless, J.W.; Crunk, A.; Curry, C.; et al. Novel 9q34.11 Gene Deletions Encompassing Combinations of Four Mendelian Disease Genes: STXBP1, SPTAN1, ENG, and TOR1A. Genet. Med. 2012, 14, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, A.; Ishii, A.; Shimojima, K.; Kurahashi, H.; Yoshitomi, S.; Imai, K.; Imamura, M.; Seki, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Hirose, S.; et al. Phenotypes of Children with 20q13.3 Microdeletion Affecting KCNQ2 and CHRNA4. Epileptic Disord. 2015, 17, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röthlisberger, B.; Hoigné, I.; Huber, A.R.; Brunschwiler, W.; Capone Mori, A. Deletion of 7q11.21–q11.23 and Infantile Spasms without Deletion of MAGI2. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2010, 152, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsi, G.; Whiting, P.; Bourdelles, B.L.; Callen, D.; Barnard, E.A.; Gurling, H. Localization of the Human NMDAR2D Receptor Subunit Gene (GRIN2D) to 19q13.1–qter, the NMDAR2A Subunit Gene to 16p13.2 (GRIN2A), and the NMDAR2C Subunit Gene (GRIN2C) to 17q24–q25 Using Somatic Cell Hybrid and Radiation Hybrid Mapping Panels. Genomics 1998, 47, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimassi, S.; Andrieux, J.; Labalme, A.; Lesca, G.; Cordier, M.P.; Boute, O.; Neut, D.; Edery, P.; Sanlaville, D.; Schluth-Bolard, C. Interstitial 12p13.1 Deletion Involving GRIN2B in Three Patients with Intellectual Disability. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2013, 161, 2564–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertossi, C.; Cassina, M.; De Palma, L.; Vecchi, M.; Rossato, S.; Toldo, I.; Donà, M.; Murgia, A.; Boniver, C.; Sartori, S. 14q12 Duplication Including FOXG1: Is There a Common Age-Dependent Epileptic Phenotype? Brain Dev. 2014, 36, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castronovo, C.; Rusconi, D.; Crippa, M.; Giardino, D.; Gervasini, C.; Milani, D.; Cereda, A.; Larizza, L.; Selicorni, A.; Finelli, P. A Novel Mosaic NSD1 Intragenic Deletion in a Patient with an Atypical Phenotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2013, 161, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambot, S.; Masurel, A.; El Chehadeh, S.; Mosca-Boidron, A.L.; Thauvin-Robinet, C.; Lefebvre, M.; Marle, N.; Thevenon, J.; Perez-Martin, S.; Dulieu, V.; et al. 9q33.3q34.11 Microdeletion: New Contiguous Gene Syndrome Encompassing STXBP1, LMX1B and ENG Genes Assessed Using Reverse Phenotyping. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.L.; Xie, J.; Ding, M.Q.; Lu, M.Z.; Zhang, L.F.; Yao, X.H.; Hu, B.; Lu, W.S.; Zheng, X.D. NEDD4 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism rs2271289 Is Associated with Keloids in Chinese Han Population. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saito, F.; Kajii, T.S.; Oka, A.; Ikuno, K.; Iida, J. Genome-Wide Association Study for Mandibular Prognathism Using Microsatellite and Pooled DNA Method. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 152, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, M.; Takano, K.; Tsuyusaki, Y.; Yoshitomi, S.; Shimono, M.; Aoki, Y.; Kato, M.; Aida, N.; Mizuguchi, T.; Miyatake, S.; et al. WDR45 Mutations in Three Male Patients with West Syndrome. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 61, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Valles-Ibáñez, G.; Hildebrand, M.S.; Bahlo, M.; King, C.; Coleman, M.; Green, T.E.; Goldsmith, J.; Davis, S.; Gill, D.; Mandelstam, S.; et al. Infantile-Onset Myoclonic Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy: A New RARS2 Phenotype. Epilepsia Open 2022, 7, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Serrano, M.; Coote, D.J.; Azmanov, D.; Goullee, H.; Andersen, E.; McLean, C.; Davis, M.; Ishimura, R.; Stark, Z.; Vallat, J.M.; et al. A Homozygous UBA5 Pathogenic Variant Causes a Fatal Congenital Neuropathy. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 57, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadia, J.; Li, Y.; Walano, N.; Deputy, S.; Gajewski, K.; Andersson, H.C. Genotype–Phenotype Correlation in IARS2-Related Diseases: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e05401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, N.; Ogaya, S.; Nakashima, M.; Nishijo, T.; Sugawara, Y.; Iwamoto, I.; Ito, H.; Maki, Y.; Shirai, K.; Baba, S.; et al. De Novo PHACTR1 Mutations in West Syndrome and Their Pathophysiological Effects. Brain 2018, 141, 3098–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lv, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Dorf, M.; Li, S.; Fu, B. ATP2A2 Regulates STING1/MITA-Driven Signal Transduction Including Selective Autophagy. Autophagy 2025, 21, 2230–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-González, C.; Rosas-Alonso, R.; Rodríguez-Antolín, C.; García-Guede, A.; Ibáñez de Cáceres, I.; Sanguino, J.; Pascual, S.I.; Esteban, I.; Pozo, A.D.; Mori, M.Á.; et al. Symptomatic Heterozygous X-Linked Myotubular Myopathy Female Patient with a Large Deletion at Xq28 and Decreased Expression of the Normal Allele. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2021, 64, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Cao, X.; Yin, F.; Wu, T.; Stauber, T.; Peng, J. West Syndrome Caused by a Chloride/Proton Exchange–Uncoupling CLCN6 Mutation Related to Autophagic–Lysosomal Dysfunction. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 2990–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lee, Y.; Han, K. Neuronal Function and Dysfunction of CYFIP2: From Actin Dynamics to Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy. BMB Rep. 2019, 52, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, M.; Kato, M.; Aoto, K.; Shiina, M.; Belal, H.; Mukaida, S.; Kumada, S.; Sato, A.; Zerem, A.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; et al. De Novo Hotspot Variants in CYFIP2 Cause Early-Onset Epileptic Encephalopathy. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 83, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, W.; Ikemoto, S.; Togashi, N.; Miyabayashi, T.; Nakajima, E.; Hamano, S.I.; Shibuya, M.; Sato, R.; Takezawa, Y.; Okubo, Y.; et al. Phenotype–Genotype Correlations in Patients with GNB1 Gene Variants, Including the First Three Reported Japanese Patients to Exhibit Spastic Diplegia, Dyskinetic Quadriplegia, and Infantile Spasms. Brain Dev. 2020, 42, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nittis, P.; Efthymiou, S.; Sarre, A.; Guex, N.; Chrast, J.; Putoux, A.; Sultan, T.; Raza Alvi, J.; Ur Rahman, Z.; Zafar, F.; et al. Inhibition of G-Protein Signalling in Cardiac Dysfunction of Intellectual Developmental Disorder with Cardiac Arrhythmia (IDDCA) Syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2021, 58, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moortgat, S.; Berland, S.; Aukrust, I.; Maystadt, I.; Baker, L.; Benoit, V.; Caro-Llopis, A.; Cooper, N.S.; Debray, F.G.; Faivre, L.; et al. HUWE1 Variants Cause Dominant X-Linked Intellectual Disability: A Clinical Study of 21 Patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvertino, S.; Hartill, V.; Colyer, A.; Garner, T.; Nair, N.; Al-Gazali, L.; Canham, N.; Faundes, V.; Flinter, F.; Hertecant, J.; et al. A Restricted Spectrum of Missense KMT2D Variants Cause a Multiple Malformations Disorder Distinct from Kabuki Syndrome. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Kessi, M.; Mao, L.; He, F.; Zhang, C.; Chen, C.; Pang, N.; Yin, F.; Pan, Z.; Peng, J. Etiologic Classification of 541 Infantile Spasms Cases: A Cohort Study. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 774828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guey, S.; Hervé, D.; Kossorotoff, M.; Ha, G.; Aloui, C.; Bergametti, F.; Arnould, M.; Guenou, H.; Hadjadj, J.; Teklali, F.D.; et al. Biallelic Variants in NOS3 and GUCY1A3, the Two Major Genes of the Nitric Oxide Pathway, Cause Moyamoya Cerebral Angiopathy. Hum. Genomics 2023, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonen, M.; Fassad, M.; Patel, K.; Bisschoff, M.; Vorster, A.; Makwikwi, T.; Human, R.; Lubbe, E.; Nonyane, M.; Vorster, B.C.; et al. Biallelic Variants in RYR1 and STAC3 Are Predominant Causes of King–Denborough Syndrome in an African Cohort. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 33, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, C.; Roston, T.M.; van der Werf, C.; Sanatani, S.; Chen, S.R.W.; Wilde, A.A.M.; Krahn, A.D. RYR2-Ryanodinopathies: From Calcium Overload to Calcium Deficiency. Europace 2023, 25, euad156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ou, Y.; Duan, Y.; Gan, X.; Liu, H.; Cao, J. New Evidence Supports RYR3 as a Candidate Gene for Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1365314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Capponi, S.; Wakeling, E.; Marchi, E.; Li, Q.; Zhao, M.; Weng, C.; Stefan, P.G.; Ahlfors, H.; Kleyner, R.; et al. Missense Variants in TAF1 and Developmental Phenotypes: Challenges of Determining Pathogenicity. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 41, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmshurst, J.M.; Gaillard, W.D.; Vinayan, K.P.; Tsuchida, T.N.; Plouin, P.; Van Bogaert, P.; Carrizosa, J.; Elia, M.; Craiu, D.; Jovic, N.J.; et al. Summary of Recommendations for the Management of Infantile Seizures: Task Force Report for the ILAE Commission of Pediatrics. Epilepsia 2015, 56, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannesen, K.M.; Gardella, E.; Gjerulfsen, C.E.; Bayat, A.; Rouhl, R.P.W.; Reijnders, M.; Whalen, S.; Keren, B.; Buratti, J.; Courtin, T.; et al. PURA-Related Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy: Phenotypic and Genotypic Spectrum. Neurol. Genet. 2021, 7, e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Johannesen, K.M.; Hedrich, U.B.S.; Masnada, S.; Rubboli, G.; Gardella, E.; Lesca, G.; Ville, D.; Milh, M.; Villard, L.; et al. Genetic and Phenotypic Heterogeneity Suggest Therapeutic Implications in SCN2A-Related Disorders. Brain 2017, 140, 1316–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, X.; Tian, H.; Wang, L.; Guo, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, F.; Sun, T. SCN1A Mutation beyond Dravet Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 743726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magielski, J.H.; Cohen, S.; Kaufman, M.C.; Parthasarathy, S.; Xian, J.; Brimble, E.; Fitter, N.; Furia, F.; Gardella, E.; Møller, R.S.; et al. Deciphering the Natural History of SCN8A-Related Disorders. Neurology 2025, 104, e213533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, Q.; Hertecant, J.; El-Hattab, A.W.; Ali, B.R.; Suleiman, J. West Syndrome, Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy, and Severe CNS Disorder Associated with WWOX Mutations. Epileptic Disord. 2018, 20, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vals, M.A.; Ashikov, A.; Ilves, P.; Loorits, D.; Zeng, Q.; Barone, R.; Huijben, K.; Sykut-Cegielska, J.; Diogo, L.; Elias, A.F.; et al. Clinical, Neuroradiological, and Biochemical Features of SLC35A2-CDG Patients. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, A.; Schwarz, N.; Seiffert, S.; Pendziwiat, M.; Rohr, A.; van Baalen, A.; Helbig, I.; Weber, Y.; Muhle, H. Whole-Exome Sequencing in NF1-Related West Syndrome Leads to the Identification of KCNC2 as a Novel Candidate Gene for Epilepsy. Neuropediatrics 2020, 51, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jóźwiak, S.; Curatolo, P.; Kotulska, K. Intellectual Disability and Autistic Behavior and Their Modifying Factors in Children with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Brain Dev. 2025, 47, 104322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.Q.; Yao, Y.; Yang, L.Y.; Hua, Y.; Li, G.M. Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome as a New Phenotype in TOP2B Deficiency Caused by a De Novo Variant: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1542268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, B.G. The Origin of Infantile Spasms: Evidence from a Case of Hydranencephaly. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1972, 14, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Cristancho, A.G.; Dubbs, H.A.; Liu, G.T.; Cowan, N.J.; Goldberg, E.M. A Patient with Lissencephaly, Developmental Delay, and Infantile Spasms Due to De Novo Heterozygous Mutation of KIF2A. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2016, 4, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Weiss, S.K.; Minassian, B. Infantile Spasms with Periventricular Nodular Heterotopia, Unbalanced Chromosomal Translocation 3p26.2–10p15.1 and 6q22.31 Duplication. Clin. Case Rep. 2016, 4, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al Dhaibani, M.A.; El-Hattab, A.W.; Ismayl, O.; Suleiman, J. B3GALNT2-Related Dystroglycanopathy: Expansion of the Phenotype with Novel Mutation Associated with Muscle–Eye–Brain Disease, Walker–Warburg Syndrome, Epileptic Encephalopathy (West Syndrome), and Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Neuropediatrics 2018, 49, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C.; Tiné, A.; Fazio, G.; Rizzo, R.; Colognola, R.M.; Sorge, G.; Bergonzi, P.; Pavone, L. Seizures in Patients with Trisomy 21. Am. J. Med. Genet. Suppl. 1990, 7, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapp, S.; Anderson, T.; Visootsak, J. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children with Down Syndrome and Infantile Spasms. J. Pediatr. Neurol. 2015, 13, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerminara, C.; Compagnone, E.; Bagnolo, V.; Galasso, C.; Lo-Castro, A.; Brinciotti, M.; Curatolo, P. Late-Onset Epileptic Spasms in Children with Pallister–Killian Syndrome: A Report of Two New Cases and Review of the Electroclinical Aspects. J. Child Neurol. 2010, 25, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, A.L. Latest American and European Updates on Infantile Spasms. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2013, 13, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Lin, W.D.; Chou, I.C.; Lee, I.C.; Fan, H.C.; Hong, S.Y. Epileptic Spasms in PPP1CB-Associated Noonan-Like Syndrome: A Case Report with Clinical and Therapeutic Implications. BMC Neurol. 2018, 18, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anttonen, A.K.; Laari, A.; Kousi, M.; Yang, Y.J.; Jääskeläinen, T.; Somer, M.; Siintola, E.; Jakkula, E.; Muona, M.; Tegelberg, S.; et al. ZNHIT3 Is Defective in PEHO Syndrome, a Severe Encephalopathy with Cerebellar Granule Neuron Loss. Brain 2017, 140, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifiletti, R.R.; Incorpora, G.; Polizzi, A.; Cocuzza, M.D.; Bolan, E.A.; Parano, E. Aicardi Syndrome with Multiple Tumors: A Case Report with Literature Review. Brain Dev. 1995, 17, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hafid, N.; Christodoulou, J. Phenylketonuria: A Review of Current and Future Treatments. Transl. Pediatr. 2015, 4, 304–317. [Google Scholar]

- Alrifai, M.T.; AlShaya, M.A.; Abulaban, A.; Alfadhel, M. Hereditary Neurometabolic Causes of Infantile Spasms in 80 Children Presenting to a Tertiary Care Center. Pediatr. Neurol. 2014, 51, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullotta, F.; Pavone, L.; Mollica, F.; Grasso, S.; Valenti, C. Krabbe’s Disease with Unusual Clinical and Morphological Features. Neuropädiatrie 1979, 10, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, R.E.; Petrukhin, K.; Chernov, I.; Pellequer, J.L.; Wasco, W.; Ross, B.; Romano, D.M.; Parano, E.; Pavone, L.; Brzustowicz, L.M.; et al. The Wilson Disease Gene Is a Copper Transporting ATPase with Homology to the Menkes Disease Gene. Nat. Genet. 1993, 5, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smpokou, P.; Samanta, M.; Berry, G.T.; Hecht, L.; Engle, E.C.; Lichter-Konecki, U. Menkes Disease in Affected Females: The Clinical Disease Spectrum. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2015, 167, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.; Weisfeld-Adams, J.D.; Benke, T.A.; Bonnen, P.E. Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis Presenting with Infantile Spasms and Intellectual Disability. JIMD Rep. 2017, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.H.; Hur, Y.J. Glucose Transporter 1 Deficiency Presenting as Infantile Spasms with a Mutation Identified in Exon 9 of SLC2A1. Korean J. Pediatr. 2016, 59, S29–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.G.; Bahi-Buisson, N.; Barnerias, C.; Boddaert, N.; Nabbout, R.; de Lonlay, P.; Kaminska, A.; Eisermann, M. Epileptic Spasms in Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation. Epileptic Disord. 2017, 19, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Karnebeek, C.D.; Tiebout, S.A.; Niermeijer, J.; Poll-The, B.T.; Ghani, A.; Coughlin, C.R.; Van Hove, J.L.; Richter, J.W.; Christen, H.J.; Gallagher, R.; et al. Pyridoxine-Dependent Epilepsy: An Expanding Clinical Spectrum. Pediatr. Neurol. 2016, 59, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gospe, S.M., Jr. Pyridoxine-Dependent Epilepsy. In GeneReviews; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri, M.; Pascual-Castroviejo, I.; Di Rocco, C. Neurocutaneous Disorders. Phakomatoses and Hamartoneoplastic Syndromes; Springer: Wien, Austria; New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.P.; Roach, E.S. Neurocutaneous Syndromes. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; 3rd Series, No. 132; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri, M.; Praticò, A.D. Mosaic Neurocutaneous Disorders and Their Causes. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2015, 22, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curatolo, P.; Bombardieri, R.; Jozwiak, S. Tuberous Sclerosis. Lancet 2008, 372, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu-Shore, C.J.; Major, P.; Camposano, S.; Muzykewicz, D.; Thiele, E.A. The Natural History of Epilepsy in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curatolo, P.; Moavero, R.; van Scheppingen, J.; Aronica, E. mTOR Dysregulation and Tuberous Sclerosis-Related Epilepsy. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2018, 18, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, P.J.; Wilde, L.; de Vries, M.C.; Moavero, R.; Pearson, D.A.; Curatolo, P. A Clinical Update on “Tuberous Sclerosis Complex–Associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders (TAND)”. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2018, 178, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, C.; Sanguansermsri, C.; Chable, H.; Anghelina, M.; Peinhof, S. Manifestations of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: The Experience of a Provincial Clinic. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 44, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Swallow, E.; Said, Q.; Peeples, M.; Meiselbach, M.; Signorovitch, J.; Kohrman, M.; Korf, B.; Krueger, D.; Wong, M.; et al. Epilepsy Treatment Patterns among Patients with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 391, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fohlen, M.; Taussig, D.; Ferrand-Sorbets, S.; Chipaux, M.; Dorison, N.; Delalande, O.; Dorfmüller, G. Refractory Epilepsy in Preschool Children with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Early Surgical Treatment and Outcome. Seizure 2018, 60, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, S.; Lin, W.; Wang, L.; Ni, Z.; Jin, F.; Zha, X.; Fei, G. Combined Targeting of mTOR and Akt. Using. Rapamycin and MK-2206 in the Treatment of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Cancer 2017, 8, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, D.N.; Lawson, J.A.; Yapici, Z.; Ikeda, H.; Polster, T.; Nabbout, R.; Curatolo, P.; de Vries, P.J.; Dlugos, D.J.; Voi, M.; et al. Everolimus for Treatment-Refractory Seizures in TSC: Extension of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2018, 8, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashabat, M.; Al Qahtani, X.S.; Almakdob, S.; Altwaijri, W.; Ba-Armah, D.M.; Hundallah, K.; Al Hashem, A.; Al Tala, S.; Maddirevula, S.; Alkuraya, F.S.; et al. The Landscape of Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy in a Consanguineous Population. Seizure 2019, 69, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulac, O. What Is West Syndrome? Brain Dev. 2001, 23, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmshurst, J.M.; Ibekwe, R.C.; O’Callaghan, F.J.K. Epileptic Spasms—175 Years On: Trying to Teach an Old Dog New Tricks. Seizure 2017, 44, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, R.E. Investigations in West Syndrome: Which, When and Why. Pediatr. Neurol. Briefs 2015, 29, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chong, P.F.; Saitsu, H.; Sakai, Y.; Imagi, T.; Nakamura, R.; Matsukura, M.; Matsumoto, N.; Kira, R. Deletions of SCN2A and SCN3A Genes in a Patient with West Syndrome and Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Seizure 2018, 60, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W.; Rutkowski, J.; Tennekoon, G.; Gemeski, J.; Buchanan, K.; Johnston, M. Nerve Growth Factor Increases Choline Acetyltransferase Activity in Developing Basal Forebrain Neurons. Brain Res. 1986, 1, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, M.; Lindholm, D.; Bandtlov, C.; Heumann, R.; Ghahn, H.; Näher-Noe, M.; Thoenen, H. Regulation of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) Synthesis in the Rat Central Nervous System: Comparison between the Effects of Interleukin-1 and Various Growth Factors in Astrocyte Cultures and In Vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1990, 2, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaccianoce, S.; Cigliana, G.; Muscolo, L.; Porcu, A.; Navarra, D.; Perez-Polo, R.; Angelucci, L. Hypothalamic Involvement in the Activation of the Pituitary-Adrenocortical Axis by Nerve Growth Factor. Neuroendocrinology 1993, 58, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Montalcini, R.; Dal Toso, R.; Della Valle, F.; Skaper, S.; Leon, A. Update of the NGF Saga. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995, 130, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, L.; Riikonen, R.; Nawa, H.; Lindholm, D. Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor Is Increased in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Children Suffering from Asphyxia. Neurosci. Lett. 1998, 240, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riikonen, R.; Korhonen, L.; Lindholm, D. Cerebrospinal Nerve Growth Factor—A Marker of Asphyxia? Pediatr. Neurol. 1999, 20, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Riikonen, R.; Kero, P.; Simell, O. Excitatory Amino Acids in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Neonatal Asphyxia. Pediatr. Neurol. 1992, 8, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagberg, H.; Thornberg, E.; Blennow, M.; Kjellmer, I.; Lagercranz, H.; Thringer, K.; Hamberger, A.; Sandberg, M. Excitatory Amino Acids in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Asphyxiated Infants: Relationship to Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Acta Paediatr. 1993, 82, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, R.; Söderström, S.; Vanhala, S.; Ebendal, T.; Lindholm, D. West’s Syndrome: Cerebrospinal Fluid Nerve Growth Factor and Effect of ACTH. Pediatr. Neurol. 1997, 17, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, D.; Castrén, E.; Berzaghi, M.; Blöchl, A.; Thoenen, H. Activity-Dependent and Hormonal Regulation of Neurotrophin mRNA Levels in Brain—Implications for Neuronal Plasticity. J. Neurobiol. 1994, 25, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, K.; Jansen, F.; Nellist, M.; Redeker, S.; van den Ouweland, A.; Spliet, W.; van Nieuwenhuizen, O.; Troost, D.; Crino, P.; Aronica, E. Inflammatory Processes in Cortical Tubers and Subependymal Giant Cell Tumors of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Epilepsy Res. 2008, 78, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, A.; Anink, J.; Lammens, M.; Nellist, M.; Ans, M.W.; van den Ouweland, A.; Adle-Biassette, H.; Sarnat, H.B.; Flores-Sarnat, L.; Crino, P.B.; et al. Fetal Brain Lesions in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: TORC1 Activation and Inflammation. Brain Pathol. 2012, 23, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, R.; Kokki, H. CSF Nerve Growth Factor (β-NGF) Is Increased but IGF-1 Is Normal in Children with Tuberous Sclerosis and Infantile Spasms. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2019, 23, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Zou, J.; Rensing, N.; Yang, M.; Wong, M. Inflammatory Mechanisms Contribute to the Neurological Manifestations of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 80, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloe, L.; Rocco, M.L.; Bianchi, P.; Manni, L. Nerve Growth Factor: From the Early Discoveries to the Potential Clinical Use. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, P.; Russel, J.; Feldman, E. IGFs and the Nervous System. In The IGF System: Molecular Biology, Physiology and Clinical Application; Rosenfeld, C., Roberts, C., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 425–455. [Google Scholar]

- Brunson, K.; Kramár, E.; Lin, B.; Chen, Y.; Colgin, L.L.; Yanagihara, T.; Lynch, G.; Baram, T.Z. Mechanisms of Late-Onset Cognitive Decline after Early-Life Stress. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 9328–9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popowski, M.; Ferguson, H.A.; Sion, A.M.; Koller, E.; Knudsen, E.; van den Berg, C.L. Stress and IGF-I Differentially Control Cell Fate through Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) and Retinoblastoma Protein (pRB). J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 28265–28273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labandeira-Garcia, J.; Costa-Besada, M.; Labandeira, C.; Villar-Cheda, B.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A.I. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Neuroinflammation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesny, E.; Basta-Kaim, A.; Slusarczyk, J.; Trojan, E.; Glombik, K.; Regulska, M.; Leskiewicz, M.; Budziszewska, B.; Kubera, M.; Lason, W. The Impact of Prenatal Stress on Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression in the Brain of Adult Male Rats: The Possible Role of Suppression of Cytokine Signalling Proteins. J. Neuroimmunol. 2014, 276, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, R.S.; Jääskeläinen, J.; Turpeinen, U. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Is Associated with Cognitive Outcome in Infantile Spasms. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.; Janigro, D.; Heinemann, U.; Riikonen, R.; Bernard, C.; Patel, M. WONOEP Appraisal: Molecular and Cellular Biomarkers for Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, R. Insulin-Like Growth Factors in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Neurological Disorders in Children. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström, Å.; Ley, D.; Hansen-Pupp, I.; Hallberg, B.; Löfqvist, C.; van Marter, L.; van Weissenbruch, M.; Ramenghi, L.A.; Beardsall, K.; Dunger, D.; et al. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Has Multisystem Effects on Foetal and Preterm Infant Development. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, K.L.; Powel-Braxton, L.; Widmer, H.R.; Valverde, J.; Hefti, F. IGF-1 Gene Disruption Results in Reduced Brain Size, CNS Hypomyelination, and Loss of Hippocampal Granule and Striatal Parvalbumin-Containing Neurons. Neuron 1995, 14, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rener-Primec, Z.; Lozar-Krivec, J.; Krivec, U.; Neubauer, D. Head Growth in Infants with Infantile Spasms May Be Temporarily Reduced. Pediatr. Neurol. 2006, 35, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, A.; Monson, J.P. Modulation of Glucocorticoid Metabolism by the Growth Hormone–IGF-1 Axis. Clin. Endocrinol. 2007, 66, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crino, P. Focal Brain Malformations: Seizures, Signaling, Sequencing. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, L.; Peugh, L.; Ojemann, J. GABAA Receptors in Catastrophic Infantile Epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2008, 81, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.M.; Ruiz, E.; Ortega, E. Effects of CRH and ACTH Administration on Plasma and Brain Neurosteroid Levels. Neurochem. Res. 2001, 26, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Shen, H.; Gong, Q.H.; Zhou, X. Neurosteroid Regulation of GABAA Receptors: Focus on the α4 and δ Subunits. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 116, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.S. Neurosteroids: Endogenous Role in the Human Brain and Therapeutic Potentials. Prog. Brain Res. 2010, 186, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, N.C.; Gee, K.W. Neuroactive Steroid Actions at the GABAA Receptor. Horm. Behav. 1994, 28, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, B.; Cunningham, L.; Scott, G.; Mitchell, S.; Lambert, J. GABAA Receptor-Acting Neurosteroids: A Role in the Development and Regulation of the Stress Response. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2015, 36, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.; Gibbs, T.; Farb, D. Pregnenolone Sulfate as a Modulator of Synaptic Plasticity. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 3537–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riikonen, R.; Perheentupa, J. Serum Steroids and Success of Corticotropin Therapy. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1986, 75, 598–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airaksinen, E.; Tuomisto, L.; Riikonen, R. The Concentrations of GABA, 5-HIAA and HVA in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Children with Infantile Spasms and Effects of ACTH Treatment. Brain Dev. 1992, 14, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan, J.; Shields, W.; Nelson, T.; Bluestone, D.; Dodson, W.; Bourgeois, B.; Pellock, J.M.; Morton, L.D.; Monaghan, E.P. Ganaxolone for Treating Intractable Infantile Spasms: A Multicenter, Open-Label, Add-On Trial. Epilepsy Res. 2000, 42, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Poest Clement, E.; Jansen, F.E.; Braun, K.P.J.; Peters, J.M. Update on Drug Management of Refractory Epilepsy in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Paediatr. Drugs 2020, 22, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capal, J.K.; Bernardino-Cuesta, B.; Horn, P.S.; Murray, D.; Byars, A.W.; Bing, N.M.; Kent, B.; Pearson, D.A.; Sahin, M.; TACERN Study Group; et al. Influence of Seizures on Early Development in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Epilepsy Behav. 2017, 70, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, Y.; Natsume, J.; Ito, Y.; Okai, Y.; Bagarinao, E.; Yamamoto, H.; Ogaya, S.; Takeuchi, T.; Fukasawa, T.; Sawamura, F.; et al. Involvement of the Thalamus, Hippocampus, and Brainstem in Hypsarrhythmia of West Syndrome: Simultaneous Recordings of Electroencephalography and fMRI Study. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2022, 43, 1502–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Du, K.; Jia, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, F. Different Frequency Bands in Various Regions of the Brain Play Different Roles in the Onset and Wake–Sleep Stages of Infantile Spasms. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 878099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafstrom, C.E. KNOCK, KNOCK, KNOCK-IN ON GABA’S DOOR: GABRB3 Knock-in Mutation Causes Infantile Spasms in Mice. Epilepsy Curr. 2023, 23, 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shi, W.; Wan, L.; Yang, G.; Yeh, C.H. Altered Neuronal Networks in Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome: Investigation of Cross-Channel Interactions and Relapse. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, D.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, Z.; He, W.; Yan, Y.; Hou, R.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Bao, W.; He, D.; et al. Connectivity Analysis of Hypsarrhythmia-EEG for Infants with West Syndrome. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2025, 33, 1896–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Jang, H.N.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.J.; Yum, M.S.; Jeong, D.H. Identification of Topological Alterations Using Microstate Dynamics in Patients with Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si Ahmed, H.; Megherbi, L.; Daoudi, S. West Syndrome and Multiple Sclerosis Association: A Case Report. Rom. Neurosurg. 2023, 37, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, W. Altered Topological Organization of Resting-State Functional Networks in Children with Infantile Spasms. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 952940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modgil, A.; Rana, Z.S.; Sahu, J.K.; Punnakkal, P. Understanding the Neurobiology of Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome (IESS): A Comprehensive Review. Seizure 2025, 133, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaliti, G.; Pavone, P.; Marino, S.; Saporito, M.A.N.; Corsello, G.; Falsaperla, R. Molecular Mechanism Involved in the Pathogenesis of Early-Onset Epileptic Encephalopathy. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, R. Biochemical Mechanisms in the Pathogenesis of Infantile Epileptic Spasm Syndrome. Seizure 2023, 105, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekgul, H.; Serin, H.M.; Simsek, E.; Kanmaz, S.; Gazeteci, H.; Azarsiz, E.; Ozgur, S.; Yilmaz, S.; Aktan, G.; Gokben, S. CSF Levels of Neurotrophic Factors (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, Nerve Growth Factor) and Neuropeptides (Neuropeptide Y, Galanin) in Epileptic Children. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 76, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.T. More Hormones, Less Spasms: IGF-1 as a Potential Therapy for Infantile Spasms. Epilepsy Curr. 2023, 23, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phitsanuwong, C. “Time to Feed the Baby”: Should There Be a Paradigm Change in the Treatment of Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome? Epilepsy Curr. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanopoulou, A.S.; Mowrey, W.B.; Liu, W.; Katsarou, A.M.; Li, Q.; Shandra, O.; Moshé, S.L. The Multiple Hit Model of Infantile and Epileptic Spasms: The 2025 Update. Epilepsia Open 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.N.; Han, F.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.W.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.Q. Association of Serum Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Adrenocorticotropic Hormone Therapeutic Response in Patients with Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1599641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, E.A.; Han, V.X.; Patel, S.; Farrar, M.A.; Gill, D.; Mohammad, S.S.; Dale, R.C. Aetiopathogenesis of Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome and Mechanisms of Action of Adrenocorticotrophin Hormone/Corticosteroids in Children: A Scoping Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2025, 67, 1004–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanopoulou, A.S.; Moshé, S.L. Neonatal and Infantile Epilepsy: Acquired and Genetic Models. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 6, a022707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryner, R.F.; Derera, I.D.; Armbruster, M.; Kansara, A.; Sommer, M.E.; Pirone, A.; Noubary, F.; Jacob, M.; Dulla, C.G. Cortical Parvalbumin-Positive Interneuron Development and Function Are Altered in the APC Conditional Knockout Mouse Model of Infantile and Epileptic Spasms Syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 1422–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.M.; Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Moshé, S.L.; Galanopoulou, A.S. Acquired Parvalbumin-Selective Interneuronopathy in the Multiple-Hit Model of Infantile Spasms: A Putative Basis for the Partial Responsiveness to Vigabatrin Analogs? Epilepsia Open 2018, 3, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatari, V.T.; Silva, G.A.L.; Cagliari, L.L.; Valotto, M.E.; Carvalho, J.C.; Serpa, P.G.S.; Tsujigushi, G.K. Pathophysiological Basis of West Syndrome: Literature Review. Res. Soc. Dev. 2024, 13, e8613445608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.C.; Choudhary, A.; Barrett, K.T.; Gavrilovici, C.; Scantlebury, M.H. Mechanisms of Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome: What Have We Learned from Animal Models? Epilepsia 2024, 65, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascosa-Romero, M.C.; Vega, C.D.C.D.L. GABAergic Interneurons in Severe Early Epileptic Encephalopathy with a Suppression–Burst Pattern: A Continuum of Pathology. In Epileptology—The Modern State of Science; InTech: Houston, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafstrom, C.E.; Shao, L. Infantile Spasms in Pediatric Down Syndrome: Potential Mechanisms Driving Therapeutic Considerations. Children 2024, 11, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, M.; Swanson, C.I. Infantile Spasms: The Role of Prenatal Stress and Altered GABA Signaling. HAPS Educ. 2019, 23, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.M.; Moshé, S.L.; Galanopoulou, A.S. Interneuronopathies and Their Role in Early Life Epilepsies and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Epilepsia Open 2017, 2, 284–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronica, E.; Specchio, N.; Luinenburg, M.J.; Curatolo, P. Epileptogenesis in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex-Related Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy. Brain 2023, 146, 2694–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Sarnat, L. Epilepsy in Neurological Phenotypes of Epidermal Nevus Syndrome. J. Pediatr. Epilepsy 2016, 5, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Sinha, M.K. Cutaneous and Neurological Profile of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex in Children: A Case Series and Literature Review. Panacea J. Med. Sci. 2022, 12, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Lu, Q.; Yin, F.; Wang, Y.; He, F.; Wu, L.; Yang, L.; Deng, X.; Chen, C.; Peng, J. Effectiveness and Safety of Different Once-Daily Doses of Adrenocorticotropic Hormone for Infantile Spasms. Paediatr. Drugs 2017, 19, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumiloff, N.A.; Lam, W.M.; Manasco, K.B. Adrenocorticotropic Hormone for the Treatment of West Syndrome in Children. Ann. Pharmacother. 2013, 47, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alonzo, R.; Rigante, D.; Mencaroni, E.; Esposito, S. West Syndrome: A Review and Guide for Paediatricians. Clin. Drug Investig. 2018, 38, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanigasinghe, J.; Arambepola, C.; Ranganathan, S.S.; Sumanasena, S. Randomized, Single-Blind, Parallel Clinical Trial on Efficacy of Oral Prednisolone versus Intramuscular Corticotropin: A 12-Month Assessment of Spasm Control in West Syndrome. Pediatr. Neurol. 2017, 76, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, V.K.; Narayanaswamy, V.; Shivappa, S.K.; Benakappa, N.; Benakappa, A. Corticotrophin (ACTH) in Comparison to Prednisolone in West Syndrome: A Randomized Study. Indian J. Pediatr. 2019, 86, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnanayaka, V.; Jain, P.; Sharma, S.; Seth, A.; Aneja, S. Addition of Pyridoxine to Prednisolone in the Treatment of Infantile Spasms: A Pilot, Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurol. India 2018, 66, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossoff, E.H. The Modified Atkins Diet. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossoff, E.H. Infantile Spasms. Neurologist 2010, 16, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.M.; Hahn, J.; Kim, S.H.; Chang, M.J. Efficacy of Treatments for Infantile Spasms: A Systematic Review. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 40, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elterman, R.D.; Shields, W.D.; Bittman, R.M.; Torri, S.A.; Sagar, S.M.; Collins, S.D. Vigabatrin for the Treatment of Infantile Spasms: Final Report of a Randomized Trial. J. Child Neurol. 2010, 25, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvichayapat, N.; Tassniyom, S.; Treerotphon, S.; Auvichayapat, P. Treatment of Infantile Spasms with Sodium Valproate Followed by Benzodiazepines. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2007, 90, 1809–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen, J.; Komulainen, T.; Tukiainen, E.; Nordin, A.; Arola, J.; Kälviäinen, R.; Jutila, L.; Röyttä, M.; Hinttala, R.; Majamaa, K.; et al. Acute Liver Failure after Valproate Exposure in Patients with POLG1 Mutations and the Prognosis after Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014, 20, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knupp, K.G.; Leister, E.; Coryell, J.; Nickels, K.C.; Ryan, N.; Juarez-Colunga, E.; Gaillard, W.D.; Mytinger, J.R.; Berg, A.T.; Millichap, J.; et al. Response to Second Treatment after Initial Failed Treatment in a Multicenter Prospective Infantile Spasms Cohort. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 1834–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, D.N.; Belousova, E.; Sparagana, S.; Bebin, E.M.; Frost, M.D.; Kuperman, R.; Witt, O.; Kohrman, M.H.; Flamini, J.R.; Wu, J.Y.; et al. Long-Term Use of Everolimus in Patients with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Final Results from the EXIST-1 Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, T.M.; Yuan, H.; Marsh, E.D.; Fuentes-Fajardo, K.; Adams, D.R.; Markello, T.; Golas, G.; Simeonov, D.R.; Holloman, C.; Tankovic, A.; et al. GRIN2A Mutation and Early-Onset Epileptic Encephalopathy: Personalized Therapy with Memantine. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2014, 1, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalappa, B.I.; Soh, H.; Duignan, K.M.; Furuya, T.; Edwards, S.; Tzingounis, A.V.; Tzounopoulos, T. Potent KCNQ2/3-Specific Channel Activator Suppresses In Vivo Epileptic Activity and Prevents the Development of Tinnitus. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 8829–8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Gene | Cytogenetic Location | Inheritance/Pattern (Typical) | Comment/Note | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ARX | Xp21.3 | X-linked, often de novo | Classic ISs gene, migration and interneuron defect | [69] |

| 2 | CDKL5 | Xp22.13 | X-linked, often de novo | Early-onset epileptic spasms, severe DD | [70] |

| 3 | PAFAH1B1/LIS1 | 17p13.3 | AD, de novo | Lissencephaly, classic structural-spasm link | [71] |

| 4 | DCX | Xq23 | X-linked, de novo | Lissencephaly/subcortical band heterotopia | [72] |

| 5 | TUBA1A | 12q13.12 | AD, de novo | Tubulinopathy with cortical malformation | [73] |

| 6 | STXBP1 | 9q34.11 | AD, de novo | Common single-gene cause of IESS | [74] |

| 7 | KCNQ2 | 20q13.33 | AD, de novo | Severe neonatal epileptic encephalopathy | [75] |

| 8 | MAGI2 | 7q11.23 | AD, CNV/deletion | Reported in ISs, 7q11.23 region | [76] |

| 9 | GRIN2A | 16p13.2 | AD, de novo/familial | Glutamatergic receptor, ISs and other DEE | [77] |

| 10 | GRIN2B | 12p13.1 | AD, de novo | Early-onset DEE with spasms | [78] |

| 11 | FOXG1 | 14q12 | AD, de novo | Postnatal microcephaly, spasms reported | [79] |

| 12 | NSD1 | 5q35.3 | AD, de novo | Sotos phenotype, seizures/spasms | [80] |

| 13 | SPTAN1 | 9q34.11 | AD, de novo | Spasms and hypomyelination | [81] |

| 14 | NEDD4 | 15q21.3 | AD, CNV | Potential risk factor in ISs | [82] |

| 15 | CALN1 | 7q11.22 | AD, CNV/intronic deletion | Risk factor in ISs CNV studies | [83] |

| 16 | WDR45 | Xp11.23 | X-linked, de novo | Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation | [84] |

| 17 | RARS2 | 6p21.1 | AR | Pontocerebellar hypoplasia, spasms | [85] |

| 18 | UBA5 | 3q22.1 | AR | Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy | [86] |

| 19 | IARS2 | 1q41 | AR | CAGSSS spectrum, spasms | [87] |

| 20 | PHACTR1 | 6p24.1 | AD, de novo | Candidate gene in ISs cohort | [88] |

| 21 | ATP2A2 | 12q24.11 | AD | Novel candidate gene in Chinese cohort | [89] |

| 22 | CD99L2 | Xq28 | X-linked | Candidate gene in IESS cohort | [90] |

| 23 | CLCN6 | 1p36.22 | AD, de novo | Epileptic encephalopathy with spasms | [91] |

| 24 | CYFIP1 | 15q11.2 | AD, CNV | Developmental delay and seizures | [92] |

| 25 | CYFIP2 | 5q33.3 | AD, de novo | DEE with spasms | [93] |

| 26 | GNB1 | 1p36.33 | AD, de novo | DEE with hypotonia and spasms | [94] |

| 27 | GPT2 | 16q21 | AR | Metabolic DEE with spasms | [95] |

| 28 | HUWE1 | Xp11.22 | X-linked | Intellectual disability and epilepsy | [96] |

| 29 | KMT2D | 12q13.12 | AD | Kabuki spectrum, seizures in infancy | [97] |

| 30 | MYO18A | 17q11.2 | AD/AR | Candidate gene in Chinese cohort | [98] |

| 31 | NOS3 | 7q36.1 | AD | Candidate variant, possible modifier | [99] |

| 32 | RYR1 | 19q13.2 | AD/AR | Ca2+ signaling, candidate gene | [100] |

| 33 | RYR2 | 1q43 | AD | Ca2+ release channel, candidate gene | [101] |

| 34 | RYR3 | 15q13.3–q14 | AD | Candidate gene in 2020s cohorts | [102] |

| 35 | TAF1 | Xq13.1 | X-linked | DEE with early spasms | [103] |

| 36 | TECTA | 11q23.3 | AD | Candidate gene in WES screen | [104] |

| 37 | PURA | 5q31.3 | AD, de novo | PURA syndrome, seizures and spasms | [105] |

| 38 | SCN2A | 2q24.3 | AD, de novo | Common channel gene in IESS cohorts | [106] |

| 39 | SCN1A | 2q24.3 | AD, de novo/familial | ISs with Dravet-like features | [107] |

| 40 | SCN8A | 12q13.13 | AD, de novo | Early-onset DEE, spasms described | [108] |

| 41 | WWOX | 16q23.1 | AR | WWOX-related encephalopathy with spasms | [109] |

| 42 | SLC35A2 | Xp11.23 | Somatic/germline, X-linked | Mosaic ISs with focal dysplasia | [110] |

| 43 | NF1 | 17q11.2 | AD | NF1 with early-onset epileptic spasms | [111] |

| 44 | TSC2/TSC1 | 16p13.3/9q34 | AD, de novo/familial | Frequent syndromic cause of IESS | [112] |

| 45 | TOP2B | 3p24.3 | AD, de novo | Emerging gene, single recent report | [113] |

| No. | Pathogenetic/ Molecular Factor | Key Abnormality/Proposed Mechanism | Clinical or Etiologic Context | Therapeutic Implication/Target | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Disruption of cortical–subcortical networks | Early distortion of neuronal and interneuronal connectivity causes abnormal interaction between cortex, thalamus, basal ganglia and brainstem. Focal lesion can generate generalized spasms and hypsarrhythmia | Lissencephaly, polymicrogyria, cortical tubers, hydranencephaly, focal cortical lesions with generalized EEG | Early lesion localization and resection in focal cases; rationale for treating even when MRI looks focal | [66,147,148,149,150,151] |

| 2 | Genetic background for excitability and neurobehavioral phenotype | Variants in SCN2A, SCN3A and other developmental genes predispose to both epileptic spasms and ASD or cognitive delay through a shared channelopathy/synaptopathy | ISs with autism spectrum features or early developmental delay even before spasms | Genetic testing to define predisposition; possible future precision therapy | [66,147] |

| 3 | Neurotrophin imbalance (NGF, BDNF, GDNF) | After hypoxic or inflammatory injury CSF BDNF increases while NGF may decrease. In TSC or postinfectious ISs NGF can be excessively high. Both deficiency and excess can disturb synaptic maturation | Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy, postinfectious ISs, TSC with epileptic tubers | NGF modulation as experimental target; explains variable ACTH response | [152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164] |

| 4 | Low NGF in destructive or severe structural ISs | Low CSF NGF correlates with poor ACTH response and more extensive neuronal loss, probably due to limited capacity for synaptic repair | ISs with known structural or hypoxic etiology and delayed development | Early hormonal therapy before severe loss; marker of poor prognosis | [160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171] |

| 5 | IGF-1 deficiency and impaired steroid driven trophic support | Early stress, perinatal brain damage or ischemia reduces CSF IGF-1 and ACTH. This prevents mTOR-mediated survival, synaptogenesis and anti-inflammatory effects and favors epileptogenesis | Symptomatic ISs after prenatal/perinatal insults; premature infants; ISs with cerebral atrophy | IGF-1 or IGF-1 tripeptide (1–3) as adjunct; ACTH, steroids, ketogenic diet partly act through IGF-1 | [172,173,174,175,176,177] |

| 6 | Preserved IGF-1 in cryptogenic/idiopathic ISs | Normal CSF IGF-1 in infants with unknown etiology correlates with good ACTH response and better cognitive outcome | ISs with normal MRI and no early insult | Usual first line hormonal therapy is adequate | [172] |

| 7 | Experimental evidence of IGF-1 rescue | In TTX model of ISs loss of IGF-1 and astrogliosis mimicked human ISs. IGF-1 (1–3) restored inhibitory neurons, stopped spasms and normalized EEG | Experimental ISs, neonatal stroke, postsurgical epileptic spasms | IGF-1 analogues and trofinetide are promising; can reduce vigabatrin retinal toxicity | [171,173] |

| 8 | Delay or failure of GABAA developmental switch | GABA remains depolarizing in infancy if the switch is delayed. This maintains network hyperexcitability at the age when ISs occur | Early life epilepsies, symptomatic ISs, TSC, postinfectious ISs | Make GABA more effective: vigabatrin, ACTH (via neurosteroids), ketogenic diet | [178,179,180,181,182] |

| 9 | Neurosteroid deficit | Reduced production of endogenous steroids gives poor enhancement of GABAA receptors. Low DHEA/androstenedione ratio seen in non-responders to ACTH | ACTH poor responders, symptomatic ISs | Pharmacologic neurosteroids such as ganaxolone | [180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188] |

| 10 | Reduced CSF GABA in symptomatic ISs | Symptomatic etiologies show lower CSF GABA than idiopathic cases and controls, which confirms insufficient inhibitory tone | Structural/metabolic ISs with poor development | Supports use of GABAergic drugs and neurosteroid based strategies | [187,188,189,190,191] |

| 11 | Inflammatory and mTOR related epileptogenesis | In TSC and in postinfectious ISs inflammatory cells, cytokines and mTOR activation are found around epileptogenic lesions. This is paralleled by high NGF and low IGF-1 which favor seizures | TSC, postinfectious ISs, cortical tubers, mTORopathies | mTOR inhibitors, anti-inflammatory strategies, NGF modulation as adjuvant | [162,163,164,165] |

| 12 | Converging networks hypothesis | Different primary hits (genetic, structural, metabolic, inflammatory) act on the same immature network where neurotrophins, GABA, IGF-1 and HPA axis are interlinked. Any disruption gives the same hypsarrhythmic output | Explains why ISs arise from many different causes | Justifies use of ACTH, steroids, ketogenic diet, and possibly IGF-1 analogues although triggers differ | [66,147,178] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdygalyk, B.; Rabandiyarov, M.; Lepessova, M.; Koshkimbayeva, G.; Zharkinbekova, N.; Tekebayeva, L.; Zhailganov, A.; Issabekova, A.; Myrzaliyeva, B.; Tulendiyeva, A.; et al. Infantile Spasms (West Syndrome): Integrating Genetic, Neurotrophic, and Hormonal Mechanisms Toward Precision Therapy. Medicina 2025, 61, 2223. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122223

Abdygalyk B, Rabandiyarov M, Lepessova M, Koshkimbayeva G, Zharkinbekova N, Tekebayeva L, Zhailganov A, Issabekova A, Myrzaliyeva B, Tulendiyeva A, et al. Infantile Spasms (West Syndrome): Integrating Genetic, Neurotrophic, and Hormonal Mechanisms Toward Precision Therapy. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2223. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122223

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdygalyk, Bibigul, Marat Rabandiyarov, Marzhan Lepessova, Gaukhar Koshkimbayeva, Nazira Zharkinbekova, Latina Tekebayeva, Azamat Zhailganov, Alma Issabekova, Bakhytkul Myrzaliyeva, Assel Tulendiyeva, and et al. 2025. "Infantile Spasms (West Syndrome): Integrating Genetic, Neurotrophic, and Hormonal Mechanisms Toward Precision Therapy" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2223. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122223

APA StyleAbdygalyk, B., Rabandiyarov, M., Lepessova, M., Koshkimbayeva, G., Zharkinbekova, N., Tekebayeva, L., Zhailganov, A., Issabekova, A., Myrzaliyeva, B., Tulendiyeva, A., Kurmantay, A., Turmanbetova, A., & Yerkenova, S. (2025). Infantile Spasms (West Syndrome): Integrating Genetic, Neurotrophic, and Hormonal Mechanisms Toward Precision Therapy. Medicina, 61(12), 2223. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122223