Effects of the Pharmacological Modulation of NRF2 in Cancer Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. NRF2 in Oxidative Stress, Disease, and Therapeutic Modulation

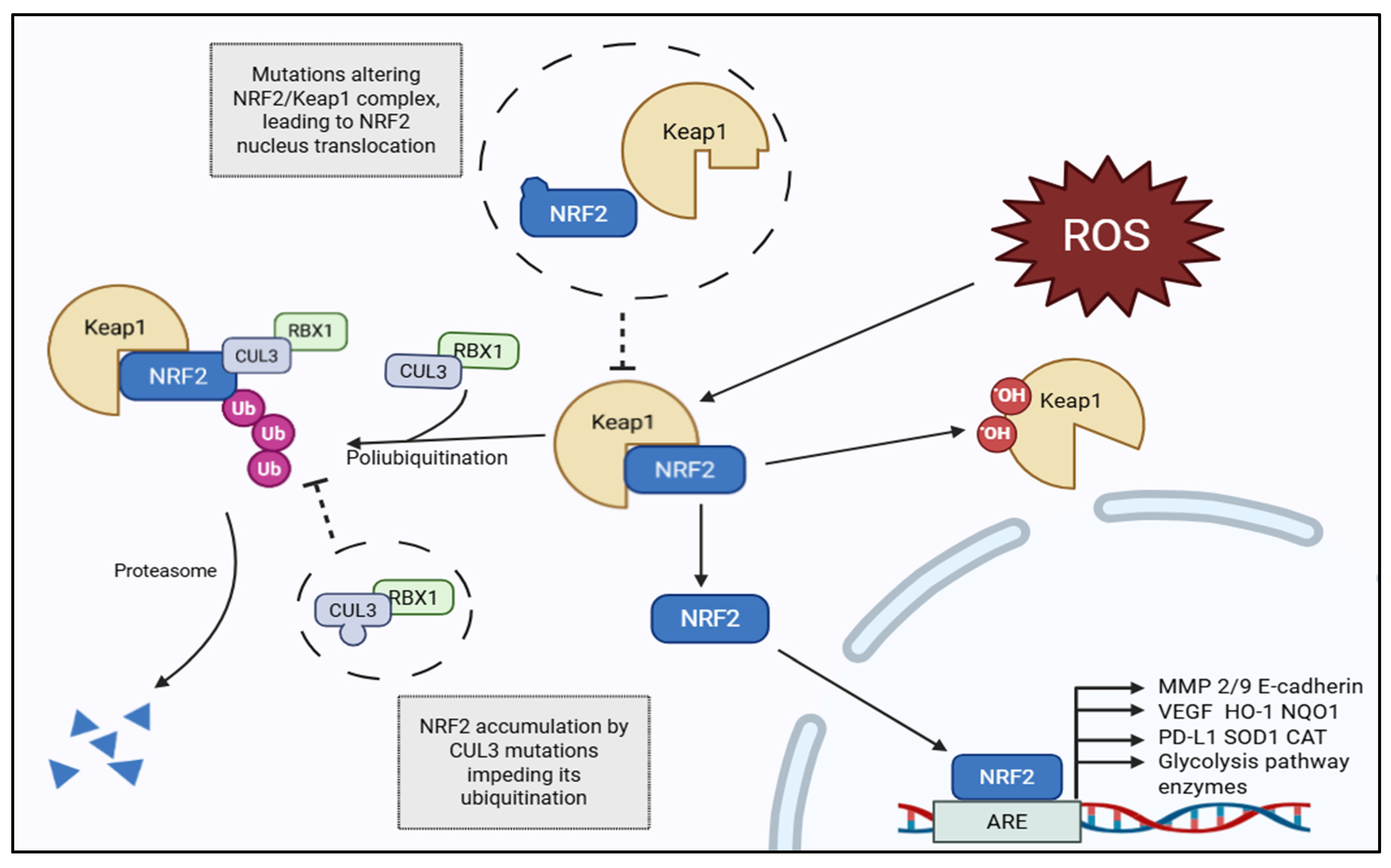

1.2. The KEAP1–NRF2–ARE Pathway: Basic Regulatory Mechanisms

1.3. NRF2 Pathogenic Activation in Cancer

1.4. Epigenetic and Non-Genetic Mechanisms of NRF2 Activation

1.5. Oncogenic and Metabolic Signaling Supporting NRF2 Dysregulation

1.6. Metabolic Reprogramming Driven by Persistent NRF2 Activation

2. NRF2 Crosstalk with Oncogenic and Inflammatory Pathways

2.1. NRF2–TGF-β Interactions During EMT

2.2. NRF2–NF-κB Crosstalk and Immunometabolic Regulation

3. Invasion Coupled with Metastasis

3.1. NRF2 as a Regulator of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

3.2. ECM Remodeling and Cytoskeletal Dynamics

3.3. Metabolic Reprogramming Supporting Invasion and Metastasis

3.4. Immune Evasion and Metastatic Colonization

3.5. Clinical Implications and Integration into TNM Progression

3.6. Pharmacological Modulation of NRF2: Mechanisms and Effects

3.6.1. Mechanistic Basis of Pharmacologic Intervention

3.6.2. NRF2 Inhibitors and Their Anti-Invasive Mechanisms

3.7. NRF2 Activators with Chemopreventive Potential

3.7.1. Targeting NRF2-Dependent Metabolic Pathways

3.7.2. Interconnected Regulatory Networks in NRF2 Pharmacological Control

4. Limitations

Discussion and Future Perspectives

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPK | MP-activated protein kinase; |

| ARE | antioxidant response element; |

| BRD4 | bromodomain-containing protein 4; |

| BSO | buthionine sulfoximine; |

| CB-839 | Telaglenastat; |

| CDDO-Me | bardoxolone methyl; |

| CUL3 | Cullin 3; |

| ECM | extracellular matrix; |

| EGCG | epigallocatechin gallate; |

| EMT | epithelial–mesenchymal transition; |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum; |

| G6PD | glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; |

| GCLC | glutamate–cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; |

| GSH | glutathione; |

| HDAC | histone deacetylase; |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha; |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1; |

| KEAP1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; |

| KRAS | Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase; |

| Maf | musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma; |

| ML385 | small-molecule NRF2 inhibitor; |

| MMP | matrix metalloproteinase; |

| mTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin; |

| MYC | myelocytomatosis oncogene; |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine; |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced form); |

| NFE2L2 | nuclear factor, erythroid 2-like 2 |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; |

| NRF2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; |

| PD-L1 | programmed death-ligand 1; |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; |

| PPP | pentose phosphate pathway; |

| RBX1 | RING-box protein 1; |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species; |

| STK11 | serine/threonine kinase 11; |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor beta; |

| TNM | tumor–node–metastasis classification system; |

| TORC | target of rapamycin complex; |

| Ub | ubiquitin; |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor; |

| WT | wild type. |

References

- Hayes, J.D.; McMahon, M.; Chowdhry, S.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. Cancer Chemoprevention Mechanisms Mediated through the Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 1713–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo de la Vega, M.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, E.J.; Giaccia, A. The Dual Roles of NRF2 in Tumor Prevention and Progression: Possible Implications in Cancer Treatment. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 79, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhiuto, C.J.; Moerland, J.A.; Leal, A.S.; Gallo, K.A.; Liby, K.T. The Multi-Faceted Consequences of NRF2 Activation throughout Carcinogenesis. Mol. Cells 2023, 46, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, S.; Patinen, T.; Jawahar Deen, A.; Pitkänen, S.; Härkönen, J.; Kansanen, E.; Küblbeck, J.; Levonen, A.-L. The KEAP1-NRF2 Pathway: Targets for Therapy and Role in Cancer. Redox Biol. 2023, 63, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.-J.; Bao, Q.-C.; Wang, L.; Guo, T.-K.; Chen, W.-L.; Xu, L.-L.; Zhou, H.-S.; Bian, J.-L.; Yang, Y.-R.; et al. NRF2 Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation and Metastasis by Increasing RhoA/ROCK Pathway Signal Transduction. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 73593–73606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lignitto, L.; LeBoeuf, S.E.; Homer, H.; Jiang, S.; Askenazi, M.; Karakousi, T.R.; Pass, H.I.; Bhutkar, A.J.; Tsirigos, A.; Ueberheide, B.; et al. Nrf2 Activation Promotes Lung Cancer Metastasis by Inhibiting the Degradation of Bach1. Cell 2019, 178, 316–329.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Wu, Q.; Lu, F.; Lei, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, N.; Yu, Y.; Ning, Z.; She, T.; et al. Nrf2 Signaling Pathway: Current Status and Potential Therapeutic Targetable Role in Human Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1184079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 Represses Nuclear Activation of Antioxidant Responsive Elements by Nrf2 through Binding to the Amino-Terminal Neh2 Domain. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, L.; Yamamoto, M. The Molecular Mechanisms Regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020, 40, e00099-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, J.W.; Niture, S.K.; Jaiswal, A.K. Nrf2:INrf2 (Keap1) Signaling in Oxidative Stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kensler, T.W.; Wakabayashi, N.; Biswal, S. Cell Survival Responses to Environmental Stresses Via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE Pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Antonucci, L.; Karin, M. NRF2 as a Regulator of Cell Metabolism and Inflammation in Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, H.; Moriguchi, T.; Takai, J.; Ebina, M.; Yamamoto, M. Nrf2 Prevents Initiation but Accelerates Progression through the Kras Signaling Pathway during Lung Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 4158–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, P.; Sorrell, F.J.; Bullock, A.N. Structural Basis of Keap1 Interactions with Nrf2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88 Pt B, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.-C.; Hannink, M. PGAM5 Tethers a Ternary Complex Containing Keap1 and Nrf2 to Mitochondria. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonelli, C.; Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.-I.; Okawa, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Zenke, Y.; Chiba, T.; Igarashi, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative Stress Sensor Keap1 Functions as an Adaptor for Cul3-Based E3 Ligase to Regulate Proteasomal Degradation of Nrf2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinan, S.B.; Gordan, J.D.; Jin, J.; Harper, J.W.; Diehl, J.A. The Keap1-BTB Protein Is an Adaptor That Bridges Nrf2 to a Cul3-Based E3 Ligase: Oxidative Stress Sensing by a Cul3-Keap1 Ligase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 8477–8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Lo, S.-C.; Cross, J.V.; Templeton, D.J.; Hannink, M. Keap1 Is a Redox-Regulated Substrate Adaptor Protein for a Cul3-Dependent Ubiquitin Ligase Complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 10941–10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggler, A.L.; Liu, G.; Pezzuto, J.M.; van Breemen, R.B.; Mesecar, A.D. Modifying Specific Cysteines of the Electrophile-Sensing Human Keap1 Protein Is Insufficient to Disrupt Binding to the Nrf2 Domain Neh2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10070–10075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggler, A.L.; Small, E.; Hannink, M.; Mesecar, A.D. Cul3-Mediated Nrf2 Ubiquitination and Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) Activation Are Dependent on the Partial Molar Volume at Position 151 of Keap1. Biochem. J. 2009, 422, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayalan Naidu, S.; Muramatsu, A.; Saito, R.; Asami, S.; Honda, T.; Hosoya, T.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Suzuki, T.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. C151 in KEAP1 Is the Main Cysteine Sensor for the Cyanoenone Class of NRF2 Activators, Irrespective of Molecular Size or Shape. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Muramatsu, A.; Saito, R.; Iso, T.; Shibata, T.; Kuwata, K.; Kawaguchi, S.; Iwawaki, T.; Adachi, S.; Suda, H.; et al. Molecular Mechanism of Cellular Oxidative Stress Sensing by Keap1. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 746–758.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Hakomäki, H.; Levonen, A.-L. Electrophilic Metabolites Targeting the KEAP1/NRF2 Partnership. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2024, 78, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Motohashi, H. The KEAP1-NRF2 System: A Thiol-Based Sensor-Effector Apparatus for Maintaining Redox Homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1169–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimta, A.-A.; Cenariu, D.; Irimie, A.; Magdo, L.; Nabavi, S.M.; Atanasov, A.G.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. The Role of Nrf2 Activity in Cancer Development and Progression. Cancers 2019, 11, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerins, M.J.; Ooi, A. A Catalogue of Somatic NRF2 Gain-of-Function Mutations in Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, H.; Motohashi, H. NRF2 Addiction in Cancer Cells. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joof, A.N.; Bajinka, O.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, F.; Tan, Y. The Central Role of NRF2 in Cancer Metabolism and Redox Signaling: Novel Insights into Crosstalk with ER Stress and Therapeutic Modulation. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 83, 4145–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, H.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Hayes, J.D. NRF2 and the Ambiguous Consequences of Its Activation during Initiation and the Subsequent Stages of Tumourigenesis. Cancers 2020, 12, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.-M.; Zhao, R.; Zhe, H. Nrf2-Mediated Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 9304091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.-H.; Huang, B.-S.; Horng, H.-C.; Yeh, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-J. Wound Healing. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. JCMA 2018, 81, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrente, L.; DeNicola, G.M. Targeting NRF2 and Its Downstream Processes: Opportunities and Challenges. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2022, 62, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Zeng, C. Current Insight into the Regulation of PD-L1 in Cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocci, F.; Tripathi, S.C.; Vilchez Mercedes, S.A.; George, J.T.; Casabar, J.P.; Wong, P.K.; Hanash, S.M.; Levine, H.; Onuchic, J.N.; Jolly, M.K. NRF2 Activates a Partial Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Is Maximally Present in a Hybrid Epithelial/Mesenchymal Phenotype. Integr. Biol. 2019, 11, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilchez Mercedes, S.A.; Bocci, F.; Ahmed, M.; Eder, I.; Zhu, N.; Levine, H.; Onuchic, J.N.; Jolly, M.K.; Wong, P.K. Nrf2 Modulates the Hybrid Epithelial/Mesenchymal Phenotype and Notch Signaling During Collective Cancer Migration. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 807324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, R.; Xu, S.; Yu, G.; Ji, L. Interplay between Nrf2 and ROS in Regulating Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition: Implications for Cancer Metastasis and Therapy. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Tang, L.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; Tu, Y. Nrf2 in Human Cancers: Biological Significance and Therapeutic Potential. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 14, 3935–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Wang, H.; Zhu, L.; Mao, L.; Qiao, L.; Su, X. The Role of Nrf2 in Migration and Invasion of Human Glioma Cell U251. World Neurosurg. 2013, 80, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Mao, A.; Guo, R.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Sun, C.; Tang, J.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Suppression of Radiation-Induced Migration of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer through Inhibition of Nrf2-Notch Axis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36603–36613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, P. The Nrf2 Transcription Factor: A Multifaceted Regulator of the Extracellular Matrix. Matrix Biol. Plus 2021, 10, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastney, M.R.; Kaivola, J.; Leppänen, V.-M.; Ivaska, J. The Role and Regulation of Integrins in Cell Migration and Invasion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, D.; Li, S.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, C.; Xia, T.; Piao, H.; et al. KEAP1 Promotes Anti-Tumor Immunity by Inhibiting PD-L1 Expression in NSCLC. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhou, X.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Hu, X.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Cao, Q.; Gu, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. High Expression of Nuclear NRF2 Combined with NFE2L2 Alterations Predicts Poor Prognosis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, H.B.; Fingleton, B.; Lee, J.Y.; Geyer, J.T.; Cesarman, E.; Parise, R.A.; Egorin, M.J.; Dezube, B.J.; Aboulafia, D.; Krown, S.E. Phase II Aids Malignancy Consortium Trial of Topical Halofuginone in Aids-Related Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2011, 56, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuishi, Y.; Taguchi, K.; Kawatani, Y.; Shibata, T.; Nukiwa, T.; Aburatani, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Motohashi, H. Nrf2 Redirects Glucose and Glutamine into Anabolic Pathways in Metabolic Reprogramming. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payandeh, Z.; Pirpour Tazehkand, A.; Mansoori, B.; Khaze, V.; Asadi, M.; Baradaran, B.; Samadi, N. The Impact of Nrf2 Silencing on Nrf2-PD-L1 Axis to Overcome Oxaliplatin Resistance and Migration in Colon Cancer Cells. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2021, 13, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Liang, L.; Huo, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhao, J.; Hu, C.; Sun, Y.; Yang, K.; et al. Tumor-Immune Microenvironment and NRF2 Associate with Clinical Efficacy of PD-1 Blockade Combined with Chemotherapy in Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, Y.; Shim, J.A.; Jeong, J.W.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.M.; Jeong, J.; Kim, S.; Im, S.-K.; Choi, D.; Lee, B.H.; et al. Targeting ROS-Sensing Nrf2 Potentiates Anti-Tumor Immunity of Intratumoral CD8+ T and CAR-T Cells. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 3879–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Suzuki, T.; Zhang, A.; Sato, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamamoto, M. NRF2 Activation in Cancer Cells Suppresses Immune Infiltration into the Tumor Microenvironment. iScience 2025, 28, 113519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciuti, B.; Garassino, M.C. Precision Immunotherapy for STK11/KEAP1-Mutant NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, L.; Wang, G.; Chen, L.; Li, C.; Jiang, X.; Gao, H.; Yang, B.; Tian, W. Prognostic and Clinicopathological Significance of NRF2 Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, N.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, S.; Chen, D.; Li, L.; He, Y.; Dong, X.; et al. NFE2L2/KEAP1 Mutations Correlate with Higher Tumor Mutational Burden Value/PD-L1 Expression and Potentiate Improved Clinical Outcome with Immunotherapy. Oncologist 2020, 25, e955–e963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, V.; Cordani, N.; Villa, A.M.; Malighetti, F.; Villa, M.; Sala, L.; Aroldi, A.; Piazza, R.; Cortinovis, D.; Mologni, L.; et al. Integrative Analysis of KEAP1/NFE2L2 Alterations across 3600+ Tumors Reveals an NRF2 Expression Signature as a Prognostic Biomarker in Cancer. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamai, T.; Murakami, S.; Arai, K.; Ishida, K.; Kijima, T. Association of Nrf2 Expression and Mutation with Weiss and Helsinki Scores in Adrenocortical Carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 2368–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamori, M.; Higa, T.; Sonoda, Y.; Murakami, S.; Dodo, M.; Kitamura, H.; Taguchi, K.; Shibata, T.; Watanabe, M.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Activation of the NRF2 Pathway and Its Impact on the Prognosis of Anaplastic Glioma Patients. Neuro-Oncology 2015, 17, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Shirota, H.; Sasaki, K.; Ouchi, K.; Nakayama, Y.; Oshikiri, H.; Otsuki, A.; Suzuki, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Ishioka, C. Specific Cancer Types and Prognosis in Patients with Variations in the KEAP1-NRF2 System: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer Sci. 2024, 115, 4034–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Kokubu, A.; Saito, S.; Narisawa-Saito, M.; Sasaki, H.; Aoyagi, K.; Yoshimatsu, Y.; Tachimori, Y.; Kushima, R.; Kiyono, T.; et al. NRF2 Mutation Confers Malignant Potential and Resistance to Chemoradiation Therapy in Advanced Esophageal Squamous Cancer. Neoplasia 2011, 13, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atyah, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, W.; Weng, J.; Wang, P.; Shi, Y.; Dong, Q.; Ren, N. The Age-Specific Features and Clinical Significance of NRF2 and MAPK10 Expression in HCC Patients. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Sun, X.; Huang, J.; Lin, W.; Zhan, Y.; Yan, J.; Xu, Y.; Wu, L.; Lian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Genomic Profiles and Prognostic Biomarkers of Resectable Lung Adenocarcinoma with a Micropapillary Component. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1574817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, H.; Suzuki, A.; Shitara, M.; Hikosaka, Y.; Okuda, K.; Moriyama, S.; Yano, M.; Fujii, Y. Genotype Analysis of the NRF2 Gene Mutation in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 31, 1135–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Shi, Q.; Xu, Z. Construction of a Lung Adenocarcinoma Prognostic Model Based on KEAP1/NRF2/HO-1 Mutation-mediated Upregulated Genes and Bioinformatic Analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2025, 29, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solis, L.M.; Behrens, C.; Dong, W.; Suraokar, M.; Ozburn, N.C.; Moran, C.A.; Corvalan, A.H.; Biswal, S.; Swisher, S.G.; Bekele, B.N.; et al. Nrf2 and Keap1 Abnormalities in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma and Association with Clinicopathologic Features. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3743–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintsala, H.R.; Jokinen, E.; Haapasaari, K.M.; Moza, M.; Ristimäki, A.R.I.; Soini, Y.; Koivunen, J.; Karihtala, P. Nrf2/Keap1 Pathway and Expression of Oxidative Stress Lesions 8-Hydroxy-2′-Deoxyguanosine and Nitrotyrosine in Melanoma. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Hämäläinen, M.; Teppo, H.-R.; Skarp, S.; Haapasaari, K.-M.; Porvari, K.; Vuopala, K.; Kietzmann, T.; Karihtala, P. NRF1 and NRF2 mRNA and Protein Expression Decrease Early during Melanoma Carcinogenesis: An Insight into Survival and MicroRNAs. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 2647068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Kamai, T.; Higashi, S.; Murakami, S.; Arai, K.; Shirataki, H.; Yoshida, K.-I. Nrf2 Gene Mutation and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Rs6721961 of the Nrf2 Promoter Region in Renal Cell Cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yao, T.; Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Xie, J.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Ge, Y.; Sun, G.; et al. Correlations of Phosphorylated Nrf2 with Responses to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. BMC Womens Health 2025, 25, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiarsky, D.; Lydon, C.A.; Chambers, E.S.; Sholl, L.M.; Nishino, M.; Skoulidis, F.; Heymach, J.V.; Luo, J.; Awad, M.M.; Janne, P.A.; et al. Molecular Markers of Metastatic Disease in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeman, F.; Nicola, F.D.; Scalera, S.; Sperati, F.; Gallo, E.; Ciuffreda, L.; Pallocca, M.; Pizzuti, L.; Krasniqi, E.; Barchiesi, G.; et al. Mutations in the KEAP1-NFE2L2 Pathway Define a Molecular Subset of Rapidly Progressing Lung Adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1924–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.; Hellyer, J.A.; Stehr, H.; Hoang, N.T.; Niu, X.; Das, M.; Padda, S.K.; Ramchandran, K.; Neal, J.W.; Wakelee, H.; et al. Role of KEAP1/NFE2L2 Mutations in the Chemotherapeutic Response of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, V.D.; Vucic, E.A.; Thu, K.L.; Pikor, L.A.; Lam, S.; Lam, W.L. Disruption of KEAP1/CUL3/RBX1 E3-Ubiquitin Ligase Complex Components by Multiple Genetic Mechanisms: Association with Poor Prognosis in Head and Neck Cancer. Head Neck 2015, 37, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namani, A.; Matiur Rahaman, M.; Chen, M.; Tang, X. Gene-Expression Signature Regulated by the KEAP1-NRF2-CUL3 Axis Is Associated with a Poor Prognosis in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Torres-Saavedra, P.A.; Zhao, X.; Major, M.B.; Holmes, B.J.; Nguyen, N.K.; Kumaravelu, P.; Hodge, T.; Diehn, M.; Zevallos, J.; et al. Association between Locoregional Failure and NFE2L2/KEAP1/CUL3 Mutations in NRG/RTOG 9512: A Randomized Trial of Radiation Fractionation in T2N0 Glottic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 1615–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, H.; Yoshida, T.; Higashiyama, R.; Torasawa, M.; Uehara, Y.; Ohe, Y. EGFR, TP53, and CUL3 Triple Mutation in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Its Potentially Poor Prognosis: A Case Report and Database Analysis. Thorac. Cancer 2025, 16, e15523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, S.; Zhang, C.; Kong, A.-N.T. Epigenetic Regulation of Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88 Pt B, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Duan, S.; Xie, Z.; Bao, W.; Xu, B.; Yang, W.; Zhou, L. Epigenetic Therapeutics Targeting NRF2/KEAP1 Signaling in Cancer Oxidative Stress. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 924817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Dashwood, R.H. Epigenetic Regulation of NRF2/KEAP1 by Phytochemicals. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Wu, R.; Guo, Y.; Kong, A.-N.T. Regulation of Keap1–Nrf2 Signaling: The Role of Epigenetics. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2016, 1, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, S.A.; Souza, D.P.D.; Kersbergen, A.; Policheni, A.N.; Dayalan, S.; Tull, D.; Rathi, V.; Gray, D.H.; Ritchie, M.E.; McConville, M.J.; et al. Synergy between the KEAP1/NRF2 and PI3K Pathways Drives Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with an Altered Immune Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 935–943.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panieri, E.; Saso, L. Potential Applications of NRF2 Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8592348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.J.; Liu, Y.; Han, S.; Yang, C. Brusatol, an NRF2 Inhibitor for Future Cancer Therapeutic. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, P.K.; Fan, P.-D.; Qeriqi, B.; Namakydoust, A.; Daly, B.; Ahn, L.; Kim, R.; Plodkowski, A.; Ni, A.; Chang, J.; et al. Targeting NFE2L2/KEAP1 Mutations in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with the TORC1/2 Inhibitor TAK-228. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2023, 18, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayanju, A.; Copple, I.M.; Bryan, H.K.; Edge, G.T.; Sison, R.L.; Wong, M.W.; Lai, Z.-Q.; Lin, Z.-X.; Dunn, K.; Sanderson, C.M.; et al. Brusatol Provokes a Rapid and Transient Inhibition of Nrf2 Signaling and Sensitizes Mammalian Cells to Chemical Toxicity—Implications for Therapeutic Targeting of Nrf2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 78, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Venkannagari, S.; Oh, K.H.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Rohde, J.M.; Liu, L.; Nimmagadda, S.; Sudini, K.; Brimacombe, K.R.; Gajghate, S.; et al. Small Molecule Inhibitor of NRF2 Selectively Intervenes Therapeutic Resistance in KEAP1-Deficient NSCLC Tumors. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 3214–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.-J.; Choi, J.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S. The Effects of ML385 on Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Implications for NRF2 Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, K.; Tsujita, T.; Hayashi, M.; Ojima, A.; Keleku-Lukwete, N.; Katsuoka, F.; Otsuki, A.; Kikuchi, H.; Oshima, Y.; Suzuki, M.; et al. Halofuginone Enhances the Chemo-Sensitivity of Cancer Cells by Suppressing NRF2 Accumulation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 103, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, H.; Rowland, N.G.; Krall, C.M.; Bowman, B.M.; Major, M.B.; Zolkind, P. NRF2 Immunobiology in Cancer: Implications for Immunotherapy and Therapeutic Targeting. Oncogene 2025, 44, 3641–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ohta, T.; Maruyama, A.; Hosoya, T.; Nishikawa, K.; Maher, J.M.; Shibahara, S.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M. BRG1 Interacts with Nrf2 To Selectively Mediate HO-1 Induction in Response to Oxidative Stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 7942–7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.D.; Hsu, A.; Williams, D.E.; Dashwood, R.H.; Stevens, J.F.; Yamamoto, M.; Ho, E. Metabolism and Tissue Distribution of Sulforaphane in Nrf2 Knockout and Wild-Type Mice. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 3171–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Yang, Y.-X.; Zhe, H.; He, Z.-X.; Zhou, S.-F. Bardoxolone Methyl (CDDO-Me) as a Therapeutic Agent: An Update on Its Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2014, 8, 2075–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, R.; Wang, Q.; Qin, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, W. The Role of Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in the Treatment of Respiratory Diseases and the Research Progress on Targeted Drugs. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, S.; Mikulskis, A.; Gold, R.; Fox, R.J.; Dawson, K.T.; Amaravadi, L. Evidence of Activation of the Nrf2 Pathway in Multiple Sclerosis Patients Treated with Delayed-Release Dimethyl Fumarate in the Phase 3 DEFINE and CONFIRM Studies. Mult. Scler. J. 2017, 23, 1875–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Magara, T.; Yoshimitsu, M.; Kano, S.; Kato, H.; Yokota, K.; Okuda, K.; Morita, A. Blockade of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Induces Immunogenic Cell Death and Accelerates Immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e008441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.T.; Kim, H.G.; Khanal, T.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, T.C.; Jeong, H.G. Metformin Inhibits Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression in Cancer Cells through Inactivation of Raf-ERK-Nrf2 Signaling and AMPK-Independent Pathways. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 271, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Jin, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Zhao, J. Metformin Suppresses Nrf2-Mediated Chemoresistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells by Increasing Glycolysis. Aging 2020, 12, 17582–17600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Guo, R.; Ren, F. Nrf2 Inhibitor, Brusatol in Combination with Trastuzumab Exerts Synergistic Antitumor Activity in HER2-Positive Cancers by Inhibiting Nrf2/HO-1 and HER2-AKT/ERK1/2 Pathways. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 9867595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juszczak, M.; Tokarz, P.; Woźniak, K. Potential of NRF2 Inhibitors—Retinoic Acid, K67, and ML-385—In Overcoming Doxorubicin Resistance in Promyelocytic Leukemia Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, H.-X.; Zhu, J.-Q.; Dou, Y.-X.; Xian, Y.-F.; Lin, Z.-X. Natural Nrf2 Inhibitors: A Review of Their Potential for Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 3029–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eryilmaz, I.E.; Colakoglu Bergel, C.; Arioz, B.; Huriyet, N.; Cecener, G.; Egeli, U. Luteolin Induces Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis via Dysregulating the Cytoprotective Nrf2-Keap1-Cul3 Redox Signaling in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 52, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Mo, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.; Jin, C. Combination of Transcriptomic and Proteomic Approaches Helps Unravel the Mechanisms of Luteolin in Inducing Liver Cancer Cell Death via Targeting AKT1 and SRC. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1450847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.R.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Cardamonin Sensitizes Tumour Cells to TRAIL through ROS- and CHOP-Mediated up-Regulation of Death Receptors and down-Regulation of Survival Proteins. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramchandani, S.; Naz, I.; Dhudha, N.; Garg, M. An Overview of the Potential Anticancer Properties of Cardamonin. Explor. Target. Anti-Tumor Ther. 2020, 1, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Farkhondeh, T.; Aschner, M.; Samarghandian, S. Resveratrol Mediates Its Anti-Cancer Effects by Nrf2 Signaling Pathway Activation. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Gao, Y. Resveratrol Ameliorates Iron Overload Induced Liver Fibrosis in Mice by Regulating Iron Homeostasis. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajka-Kuźniak, V.; Paluszczak, J.; Baer-Dubowska, W. The Nrf2-ARE Signaling Pathway: An Update on Its Regulation and Possible Role in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Pharmacol. Rep. PR 2017, 69, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, A.; Lee, Y.S. Molecular Mechanisms of Curcumin Action: Signal Transduction. BioFactors 2013, 39, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zhou, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Song, Y.; Li, T.; Ha, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Tian, J.; et al. NRF2 Plays a Critical Role in Both Self and EGCG Protection against Diabetic Testicular Damage. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 3172692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, C.L.; Huang, M.-T.; Liu, Y.; Khor, T.O.; Conney, A.H.; Kong, A.-N. Impact of Nrf2 on UVB-Induced Skin Inflammation/Photoprotection and Photoprotective Effect of Sulforaphane. Mol. Carcinog. 2011, 50, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.-K.; Kensler, T.W. Targeting NRF2 Signaling for Cancer Chemoprevention. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 244, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, M.C.; Zhang, D.D. The Emerging Role of the Nrf2-Keap1 Signaling Pathway in Cancer. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Sayin, V.I.; Davidson, S.M.; Bauer, M.R.; Singh, S.X.; LeBoeuf, S.E.; Karakousi, T.R.; Ellis, D.C.; Bhutkar, A.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; et al. Keap1 Loss Promotes Kras-Driven Lung Cancer and Results in a Dependence on Glutaminolysis. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan-Cobo, A.; Sitthideatphaiboon, P.; Qu, X.; Poteete, A.; Pisegna, M.A.; Tong, P.; Chen, P.-H.; Boroughs, L.K.; Rodriguez, M.L.M.; Zhang, W.; et al. LKB1 and KEAP1/NRF2 Pathways Cooperatively Promote Metabolic Reprogramming with Enhanced Glutamine Dependence in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 3251–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, J.W.; Frankel, P.; Shackelford, D.; Dunphy, M.; Badawi, R.D.; Nardo, L.; Cherry, S.R.; Lanza, I.; Reid, J.; Gonsalves, W.I.; et al. Phase 1 Trial of MLN0128 (Sapanisertib) and CB-839 HCl (Telaglenastat) in Patients With Advanced NSCLC (NCI 10327): Rationale and Study Design. Clin. Lung Cancer 2021, 22, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.-C.; Hsiao, J.-R.; Jiang, S.-S.; Chang, J.-Y.; Chu, P.-Y.; Liu, K.-J.; Fang, H.-L.; Lin, L.-M.; Chen, H.-H.; Huang, Y.-W.; et al. C-MYC-Directed NRF2 Drives Malignant Progression of Head and Neck Cancer via Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase and Transketolase Activation. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5232–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TeSlaa, T.; Ralser, M.; Fan, J.; Rabinowitz, J.D. The Pentose Phosphate Pathway in Health and Disease. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gureev, A.P.; Popov, V.N.; Starkov, A.A. Crosstalk between the mTOR and Nrf2/ARE Signaling Pathways as a Target in the Improvement of Long-Term Potentiation. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 328, 113285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-J.; Lin, P.-L.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.-M.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lee, H. Cytoplasmic, but Not Nuclear Nrf2 Expression, Is Associated with Inferior Survival and Relapse Rate and Response to Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 1904–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.J.; Gorski, S.M. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Autophagy-Mediated Treatment Resistance in Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, A.; Wang, X.-J.; Zhao, F.; Villeneuve, N.F.; Wu, T.; Jiang, T.; Sun, Z.; White, E.; Zhang, D.D. A Noncanonical Mechanism of Nrf2 Activation by Autophagy Deficiency: Direct Interaction between Keap1 and P62. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, Y.; Waguri, S.; Sou, Y.; Kageyama, S.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishimura, R.; Saito, T.; Yang, Y.; Kouno, T.; Fukutomi, T.; et al. Phosphorylation of P62 Activates the Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway during Selective Autophagy. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Johnston, L.J.; Wang, F.; Ma, X. Triggers for the Nrf2/ARE Signaling Pathway and Its Nutritional Regulation: Potential Therapeutic Applications of Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Xie, D.; Yu, Y.; Yao, L.; Xu, B.; Huang, L.; Wu, S.; Li, F.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. KEAP1/NFE2L2 Mutations of Liquid Biopsy as Prognostic Biomarkers in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Results From Two Multicenter, Randomized Clinical Trials. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 659200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Ku, C.-C.; Wuputra, K.; Wu, D.-C.; Yokoyama, K.K. Vulnerability of Antioxidant Drug Therapies on Targeting the Nrf2-Trp53-Jdp2 Axis in Controlling Tumorigenesis. Cells 2024, 13, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.-C.; Fan, C.-W.; Tseng, W.-K.; Chein, H.-P.; Hsieh, T.-Y.; Chen, J.-R.; Hwang, C.-C.; Hua, C.-C. The Ratio of Hmox1/Nrf2 mRNA Level in the Tumor Tissue Is a Predictor of Distant Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Dis. Markers 2016, 2016, 8143465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-C.; Fan, C.-W.; Tseng, W.-K.; Chen, J.-R.; Hua, C.-C. The Tumour/Normal Tissue Ratio of Keap1 Protein Is a Predictor for Lymphovascular Invasion in Colorectal Cancer: A Correlation Study between the Nrf2 and KRas Pathways. Biomarkers 2022, 27, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, W.; Dang, H.; Wang, B. Expression of the Nrf2 and Keap1 Proteins and Their Clinical Significance in Osteosarcoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 473, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angori, S.; Lakshminarayanan, H.; Banaei-Esfahani, A.; Mühlbauer, K.; Bolck, H.A.; Kallioniemi, O.; Pietiäinen, V.; Schraml, P.; Moch, H. Exploiting NRF2-ARE Pathway Activation in Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 156, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Zaika, A.; Que, J.; El-Rifai, W. The Antioxidant Response in Barrett’s Tumorigenesis: A Double-Edged Sword. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mutation | Cancer | Clinical Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRF2 | Adrenocortical carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [57] |

| Anaplastic glioblastoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [58] | |

| Anaplastic glioma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [58] | |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [59] | |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | Chemo and radiotherapy resistance in advanced states, and worse prognosis vs. WT | [60] | |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | High expression associated with worse overall survival | [46] | |

| Hepatocarcinoma | Worse prognosis in low expression group and disease-free survival | [61] | |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | Worse prognosis and chemosensivity vs. WT | [62] | |

| Lung squamous cell carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [63] | |

| Lung squamous cell carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [59] | |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | No difference in prognosis vs. WT | [59] | |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | Lower disease-free survival vs. WT | [64] | |

| Non-small cell lung carcinoma | Lower overall survival vs. WT | [65] | |

| Melanoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [66] | |

| Melanoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [67] | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [68] | |

| Triple-negative breast cancer | Higher pNRF2 levels predicted worse response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy | [69] | |

| KEAP1 | Esophageal squamous carcinoma | No difference in prognosis vs. WT | [59] |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | No difference in prognosis vs. WT | [59] | |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | Higher rate of mutated KEAP1 in lymph node and distant metastasis patients, lower overall survival vs. WT | [70] | |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | Lower progression-free survival and overall survival vs. WT | [71] | |

| Lung squamous cell carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [59] | |

| Non-small cell lung carcinoma | Lower overall survival vs. WT | [65] | |

| Non-small cell lung carcinoma | Shorter time to treatment failure and worse overall survival vs. WT | [72] | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | No difference in prognosis vs. WT | [68] | |

| CUL3 | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [73] |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [74] | |

| Glottic cell squamous cell carcinoma | Worse prognosis vs. WT | [75] | |

| Non-small cell lung carcinoma | Lower overall survival vs. WT | [76] |

| Drug | Dose | Mechanism of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brusatol | Not standardized | Promotes NRF2 degradation; sensitizes tumors | [83,85] |

| ML385 | Not standardized | Blocks NRF2 DNA binding | [86,87] |

| Halofuginone | Not standardized | Inhibits TGF-β/Smad; reduces NRF2 accumulation | [88,89] |

| Sulforaphane | 5–20 μM | KEAP1 cysteine alkylation → NRF2 activation | [90,91] |

| CDDO-Me (bardoxolone) | 10–100 nM | Electrophilic covalent activation of NRF2 | [92,93] |

| Dimethyl fumarate | 240 mg/day | Electrophilic KEAP1 modification | [94] |

| CB-839 (Telaglenastat) | Not standardized | Glutaminase inhibitor | [84] |

| G6PD inhibitors | Not standardized | Blocks PPP/NADPH production | [95] |

| PI3K/mTOR inhibitors | Not standardized | Reduces NRF2 stabilization | [35] |

| Metformin | 250–2000 mg/day | AMPK activation suppresses NRF2 chemoresistance | [96,97] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gelerstein-Claro, S.; Méndez-Valdés, G.; Rodrigo, R. Effects of the Pharmacological Modulation of NRF2 in Cancer Progression. Medicina 2025, 61, 2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122224

Gelerstein-Claro S, Méndez-Valdés G, Rodrigo R. Effects of the Pharmacological Modulation of NRF2 in Cancer Progression. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122224

Chicago/Turabian StyleGelerstein-Claro, Santiago, Gabriel Méndez-Valdés, and Ramón Rodrigo. 2025. "Effects of the Pharmacological Modulation of NRF2 in Cancer Progression" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122224

APA StyleGelerstein-Claro, S., Méndez-Valdés, G., & Rodrigo, R. (2025). Effects of the Pharmacological Modulation of NRF2 in Cancer Progression. Medicina, 61(12), 2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122224