Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Gestational Diabetes Using Different Diagnostic Criteria: A Study from the Northern Adriatic Region of Croatia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Obstetric and Neonatal Outcomes

2.3. Main Exposure and Covariates

- GDM diagnosed and treated according to the IADPSG criteria (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.1 mmol/L and/or 1 h plasma glucose ≥ 10.0 mmol/L and/or 2 h plasma glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/L).

- Diabetes mellitus in pregnancy retrospectively identified according to WHO-2006 criteria (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L and/or 2 h plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L).

- GDM retrospectively identified according to CDA-2013 criteria (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.3 mmol/L and/or 1 h plasma glucose ≥ 10.6 mmol/L and/or 2 h plasma glucose ≥ 9.0 mmol/L).

- GDM retrospectively identified according to Tomic et al. [14] criteria, based on a study of our population (1 h plasma glucose ≥ 7.9 mmol/L and 2 h plasma glucose ≥ 7.5 mmol/L).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample Characteristics

3.2. Pregnancy Outcomes Based on Four Diagnostic Criteria

3.3. Prediction of Pregnancy Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CDA | Canadian Diabetes Association |

| CS | Cesarean section |

| CS CPD | Cesarean section due to cephalopelvic disproportion |

| GDM | Gestational diabetes mellitus |

| IADPSG | International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups |

| LGA | Large-for-gestational-age |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| OGTT | Oral glucose tolerance test |

| PG | Plasma glucose |

| SGA | Small-for-gestational-age |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Catalano, P.M.; Tyzbir, E.D.; Roman, N.M.; Amini, S.B.; Sims, E.A. Longitudinal changes in insulin release and insulin resistance in nonobese pregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991, 165, 1667–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel; Metzger, B.E.; Gabbe, S.G.; Persson, B.; Buchanan, T.A.; Catalano, P.A.; Damm, P.; Dyer, A.R.; de Leiva, A.; Hod, M.; et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.S.; Wang, M.C.; Freaney, P.M.; Perak, A.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Kandula, N.R.; Gunderson, E.P.; Bullard, K.M.; Grobman, W.A.; O’Brien, M.J.; et al. Trends in gestational diabetes at first live birth by race and ethnicity in the US, 2011–2019. JAMA 2021, 326, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukwuemeka, S.; Chivese, T.; Gopinath, A.; Obikeze, K. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e058625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotă, A.; Petca, A. Gestational diabetes mellitus: The dual risk of small and large for gestational age—A narrative review. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Luo, C.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, F. Gestational diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 377, e067946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troìa, L.; Ferrari, S.; Dotta, A.; Giacomini, S.; Mainolfi, E.; Spissu, F.; Tivano, A.; Libretti, A.; Surico, D.; Remorgida, V. Does insulin treatment affect umbilical artery Doppler indices in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes? Healthcare 2024, 12, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, C.A.; Samuel, D.; McCowan, L.M.E.; Edlin, R.; Tran, T.; McKinlay, C.J.; GEMS Trial Group. Lower versus higher glycemic criteria for diagnosis of gestational diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, H.D.; Jensen, D.M.; Jensen, R.C.; Kyhl, H.B.; Jensen, T.K.; Glintborg, D.; Andersen, M. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Does one size fit all? A challenge to uniform worldwide diagnostic thresholds. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, O. How should we screen for gestational diabetes? Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 26, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behboudi-Gandevani, S.; Amiri, M.; Bidhendi-Yarandi, R.; Ramezani Tehrani, F. The impact of diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes on its prevalence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diagnostic Criteria and Classification of Hyperglycaemia First Detected in Pregnancy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee; Feig, D.S.; Berger, H.; Donovan, L.; Godbout, A.; Kader, T.; Keely, E.; Sanghera, R. Diabetes and pregnancy. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42 (Suppl. S1), S255–S282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, V.; Petrović, O.; Crnčević Orlić, Z.; Mandić, V. Gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcome—Do we have the right diagnostic criteria? J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013, 26, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Healthy Lifestyle—WHO Recommendations, WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Erez, O.; Romero, R.; Jung, E.; Chaemsaithong, P.; Bosco, M.; Suksai, M.; Gallo, D.M.; Gotsch, F. Preeclampsia and eclampsia: The conceptual evolution of a syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226 (Suppl. S2), S786–S803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, A.; Herr, D.; Solomayer, E.F.; Meyberg-Solomayer, G. Polyhydramnios: Causes, diagnosis and therapy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2013, 73, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanmode, A.M.; Mahdy, H. Macrosomia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Prpić, I.; Krajina, R.; Radić, J.; Petrović, O.; Mamula, O.; Haller, H.; Bazdarić, K.; Vukelić Sarunić, A. Birth weight and length of newborns at University Hospital Rijeka. Gynaecol. Perinatol. 2007, 16, 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlicev, M.; Romero, R.; Mitteroecker, P. Evolution of the human pelvis and obstructed labor: New explanations of an old obstetrical dilemma. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.S.; Sletner, L.; Jenum, A.K.; Øverby, N.C.; Stafne, S.N.; Qvigstad, E.; Pripp, A.H.; Sagedal, L.R. Adverse pregnancy outcomes among women in Norway with gestational diabetes using three diagnostic criteria. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Peck, E.A.; Vining, G.G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, M.M.; Dhatt, G.S.; Othman, Y. Gestational diabetes: Differences between the current international diagnostic criteria and implications of switching to IADPSG. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2015, 29, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyadzhieva, M.V.; Atanasova, I.; Zacharieva, S.; Tankova, T.; Dimitrova, V. Comparative analysis of current diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet. Med. 2012, 5, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todi, S.; Sagili, H.; Kamalanathan, S.K. Comparison of IADPSG and NICE criteria for diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M.; Juan, J.; Wang, X. Association of gestational diabetes mellitus with adverse pregnancy outcomes and its interaction with maternal age in Chinese urban women. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 5516937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycaemia and adverse pregnancy outcome (HAPO) study: Associations with maternal body mass index. BJOG 2010, 117, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Dong, W.; Shangguan, F.; Li, H.; Yu, H.; Shen, J.; Su, Y.; Li, Z. Risk factors of large for gestational age among pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e092888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E.A. Diagnosing gestational diabetes. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberico, S.; Montico, M.; Barresi, V.; Monasta, L.; Businelli, C.; Soini, V.; Erenbourg, A.; Ronfani, L.; Maso, G. The role of gestational diabetes, pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain on risk of newborn macrosomia: Results from a prospective multicentre study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moazzami, M.; Prabu, S.; Venkatesan, N.; Sankaran Rajagopalan, K.; Takawy, M.; Hegazi, M.; Rose, C.H.; Vella, A.; Egan, A.M. Gestational diabetes mellitus: The impact of body mass index on clinical outcomes. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosson, E.; Vicaut, E.; Tatulashvili, S.; Portal, J.; Nachtergaele, C.; Sal, M.; Berkane, N.; Pinto, S.; Rezgani, A.; Carbillon, L.; et al. Residual risk of large-for-gestational-age infants in treated gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2022, 48, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | C (25–75) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 31 (28–34) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7 (20.8–25.6) |

| Underweight < 18.5 kg/m2, n (%) | 96 (4.4) |

| Normal weight 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, n (%) | 1447 (66.3) |

| Overweight 25–29.9 kg/m2, n (%) | 449 (20.6) |

| Obese ≥ 30.0 kg/m2, n (%) | 191 (8.7) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 326 (14.9) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 4.7 (4.4–5.0) |

| 1 h plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 7.1 (5.9–8.5) |

| 2 h plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 5.7 (4.8–6.7) |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 40.0 (39.0–40.0) |

| Birthweight (g) | |

| Male neonates | 3590 (3260–3920) |

| Female neonates | 3440 (3150–3720) |

| LGA, 90th percentile, n (%) | 245 (11.2) |

| SGA, 5th percentile, n (%) | 104 (4.8) |

| SGA, 10th percentile, n (%) | 211 (9.7) |

| Preterm birth, n (%) | 93 (4.3) |

| Hypertension in pregnancy, n (%) | 92 (4.2) |

| Caesarean section, n (%) | 286 (13.1) |

| Complications, overall, n (%) | 791 (36.2) |

| Variable | IADPSG Criteria | WHO Criteria | CDA Criteria | Tomic et al. Criteria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-GDM n = 1775 (81.3%) | GDM n = 408 (18.7%) | p | Non-GDM n = 2168 (99.3%) | GDM n = 15 (0.7%) | p | Non-GDM n = 1946 (89.1%) | GDM n = 237 (10.9%) | p | Non-GDM n = 2000 (91.6%) | GDM n = 183 (8.4%) | p | |

| C (25–75) or n (%) | C (25–75) or n (%) | C (25–75) or n (%) | C (25–75) or n (%) | |||||||||

| Maternal age | 31.0 (28.0–34.0) | 32.0 (29.0–35.5) | <0.001 | 31.0 (28.0–34.0) | 36.0 (32.3–38.5) | / | 31.0 (28.0–34.0) | 33.0 (29.0–36.0) | <0.001 | 31.0 (28.0–34.0) | 33.0 (30.3–36.0) | <0.001 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 22.3 (20.5–25.0) | 24.8 (22.1–28.8) | <0.001 | 22.6 (20.7–25.5) | 31.5 (27.1–32.9) | / | 22.3 (20.5–25.0) | 25.1 (22.6–29.1) | <0.001 | 22.5 (20.7–25.3) | 24.5 (21.9–28.2) | <0.001 |

| Underweight | 84 (4.7) | 12 (2.9) | <0.001 | 96 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | / | 94 (4.8) | 2 (0.8) | <0.001 | 93 (4.6) | 3 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Normal weight | 1243 (70.0) | 204 (50.0) | 1444 (66.7) | 3 (20.0) | 1332 (68.5) | 115 (48.5) | 1350 (67.5) | 97 (53.0) | ||||

| Overweight | 339 (19.1) | 110 (27.0) | 445 (20.5) | 4 (26.7) | 381 (19.6) | 68 (28.7) | 405 (20.3) | 44 (24.0) | ||||

| Obesity | 109 (6.1) | 82 (20.1) | 183 (8.4) | 8 (53.3) | 139 (7.1) | 52 (21.9) | 152 (7.6) | 39 (21.3) | ||||

| Smoking, n = 326 | 268 (15.1) | 58 (14.2) | 0.608 | 324 (14.9) | 2 (13.3) | / | 289 (14.9) | 37 (15.6) | 0.685 | 303 (15.2) | 23 (12.6) | 0.466 |

| Fasting PG | 4.6 (4.4–4.8) | 5.2 (5.1–5.4) | <0.001 | 4.6 (4.4–5.0) | 5.9 (5.5–7.7) | / | 4.6 (4.4–4.8) | 5.4 (5.1–5.6) | <0.001 | 4.6 (4.4–4.9) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) | <0.001 |

| 1 h PG | 6.6 (5.5–7.8) | 9.1 (7.3–10.6) | <0.001 | 7.0 (5.9–8.4) | 11.9 (11.4–12.9) | / | 6.8 (5.7–8.1) | 10.2 (8.3–11.2) | <0.001 | 6.8 (5.7–8.0) | 10.1 (8.9–11.2) | <0.001 |

| 2 h PG | 5.4 (4.6–6.3) | 6.7 (5.6–8.4) | <0.001 | 5.7 (4.8–6.7) | 11.5 (11.1–12.4) | / | 5.5 (4.7–6.4) | 7.3 (5.0–9.1) | <0.001 | 5.5 (4.7–6.3) | 8.4 (7.9–9.5) | <0.001 |

| Primipara, n = 1215 | 1008 (56.8) | 207 (50.7) | 0.028 | 1209 (55.8) | 6 (40.0) | / | 1103 (56.7) | 112 (47.3) | 0.003 | 1118 (55.9) | 97 (53.0) | 0.434 |

| Variable | IADPSG Criteria | WHO Criteria | CDA Criteria | Tomic et al. Criteria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-GDM n = 1775 (81.3%) | GDM n = 408 (18.7%) | p | Non-GDM n = 2168 (99.3%) | GDM n = 15 (0.7%) | p | Non-GDM n = 1946 (89.1%) | GDM n = 237 (10.9%) | p | Non-GDM n = 2000 (91.6%) | GDM n = 183 (8.4%) | p | |

| C (25–75) or n (%) | C (25–75) or n (%) | C (25–75) or n (%) | C (25–75) or n (%) | |||||||||

| Complications, n = 791 | 601 (33.9) | 190 (46.6) | <0.001 | 779 (35.9) | 12 (80.0) | / | 673 (34.6) | 118 (49.8) | <0.001 | 696 (34.8) | 95 (51.9) | <0.001 |

| Maternal/Obstetric Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension n = 92 | 52 (2.9) | 40 (9.8) | <0.001 | 87 (4.0) | 5 (33.3) | / | 60 (3.1) | 32 (13.5) | <0.001 | 71 (3.5) | 21 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| CS CPD, n = 136 | 107 (6.0) | 29 (7.1) | 0.416 | 133 (6.1) | 3 (20.0) | / | 117 (6.0) | 19 (8.0) | 0.228 | 120 (6.0) | 16 (8.7) | 0.142 |

| CS, total, n = 286 | 214 (12.1) | 72 (17.6) | 0.001 | 281 (13.0) | 5 (33.3) | / | 244 (12.5) | 42 (17.7) | 0.034 | 253 (12.7) | 33 (18.0) | 0.058 |

| Polyhydramnios n = 22 | 10 (0.6) | 12 (2.9) | 0.001 | 20 (0.9) | 2 (13.3) | / | 15 (0.8) | 7 (3.0) | 0.001 | 17 (0.9) | 5 (2.7) | 0.015 |

| Fetal/Neonatal Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Macrosomia, n = 343 | 260 (14.6) | 83 (20.3) | 0.003 | 336 (15.5) | 7 (46.7) | / | 291 (15.0) | 52 (21.9) | 0.032 | 298 (14.9) | 45 (25.3) | <0.001 |

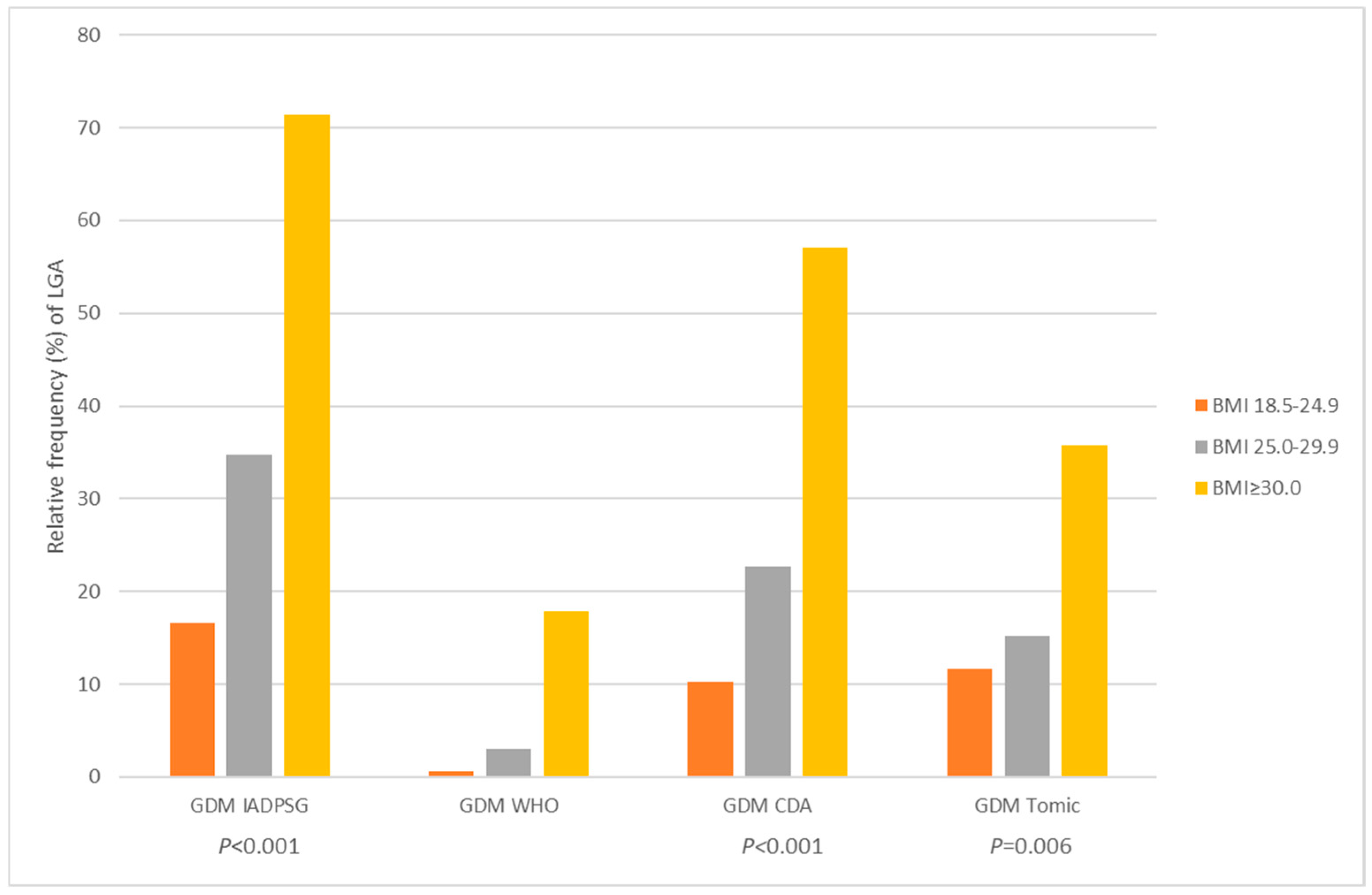

| LGA, n = 245 | 177 (10.0) | 68 (16.7) | <0.001 | 237 (10.9) | 8 (53.3) | / | 199 (10.2) | 46 (19.4) | <0.001 | 208 (10.4) | 37 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| SGA, n = 211 | 174 (9.8) | 37 (9.1) | 0.651 | 210 (9.7) | 1 (6.7) | / | 190 (9.8) | 21 (8.9) | 0.657 | 196 (9.8) | 15 (8.2) | 0.482 |

| Hypoglycemia, n = 8 | 3 (0.2) | 5 (1.2) | <0.001 | 8 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | / | 6 (0.3) | 2 (0.8) | 0.198 | 6 (0.3) | 2 (1.1) | 0.089 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia, n = 234 | 170 (9.6) | 64 (15.7) | <0.001 | 230 (10.6) | 4 (26.7) | / | 190 (9.8) | 44 (18.6) | <0.001 | 202 (10.1) | 32 (17.5) | 0.002 |

| NICU, n = 34 | 24 (1.4) | 10 (2.5) | 0.106 | 33 (1.5) | 1 (6.7) | / | 28 (1.4) | 6 (2.5) | 0.200 | 29 (1.5) | 5 (2.7) | 0.180 |

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDM based on IADPSG criteria | 1.12 | 0.72 | 1.73 | 0.630 |

| GDM based on CDA criteria | 1.27 | 0.74 | 2.18 | 0.384 |

| GDM based on Tomic et al. criteria | 2.02 | 1.30 | 3.15 | 0.002 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, overweight | 1.13 | 0.84 | 1.52 | 0.433 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, obese | 1.25 | 0.83 | 1.87 | 0.290 |

| Gestational weight gain, excessive | 2.00 | 1.48 | 2.69 | <0.001 |

| Cigarette smoking | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.73 | <0.001 |

| Parity | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.90 | <0.001 |

| Gestational age at delivery | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Mother’s age | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.101 |

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | Lower 95%CI | Upper 95%CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDM based on IADPSG criteria | 1.17 | 0.58 | 2.36 | 0.655 |

| GDM based on CDA criteria | 0.75 | 0.33 | 1.73 | 0.505 |

| GDM based on Tomic et al. criteria | 0.70 | 0.36 | 1.36 | 0.292 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, overweight | 1.72 | 1.13 | 2.63 | 0.012 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, obese | 1.94 | 1.08 | 3.51 | 0.027 |

| Gestational weight gain, excessive | 1.83 | 1.14 | 2.93 | 0.012 |

| Cigarette smoking | 0.81 | 0.50 | 1.31 | 0.864 |

| Parity | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.62 | <0.001 |

| Gestational age at delivery | 1.29 | 1.10 | 1.50 | <0.001 |

| Mother’s age | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.118 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plisic, I.; Petrovic, O.; Sopta Primorac, G.; Bazdaric, K.; Klaric, M.; Jurisic-Erzen, D. Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Gestational Diabetes Using Different Diagnostic Criteria: A Study from the Northern Adriatic Region of Croatia. Medicina 2025, 61, 2218. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122218

Plisic I, Petrovic O, Sopta Primorac G, Bazdaric K, Klaric M, Jurisic-Erzen D. Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Gestational Diabetes Using Different Diagnostic Criteria: A Study from the Northern Adriatic Region of Croatia. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2218. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122218

Chicago/Turabian StylePlisic, Iva, Oleg Petrovic, Gabrijela Sopta Primorac, Ksenija Bazdaric, Marko Klaric, and Dubravka Jurisic-Erzen. 2025. "Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Gestational Diabetes Using Different Diagnostic Criteria: A Study from the Northern Adriatic Region of Croatia" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2218. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122218

APA StylePlisic, I., Petrovic, O., Sopta Primorac, G., Bazdaric, K., Klaric, M., & Jurisic-Erzen, D. (2025). Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Gestational Diabetes Using Different Diagnostic Criteria: A Study from the Northern Adriatic Region of Croatia. Medicina, 61(12), 2218. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122218