Microcalcification and Irregular Margins as Key Predictors of Thyroid Cancer: Integrated Analysis of EU-TIRADS, Bethesda, and Histopathology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Patient Data

2.2. Ethics Committee Approvals

2.3. Statistical Analysis

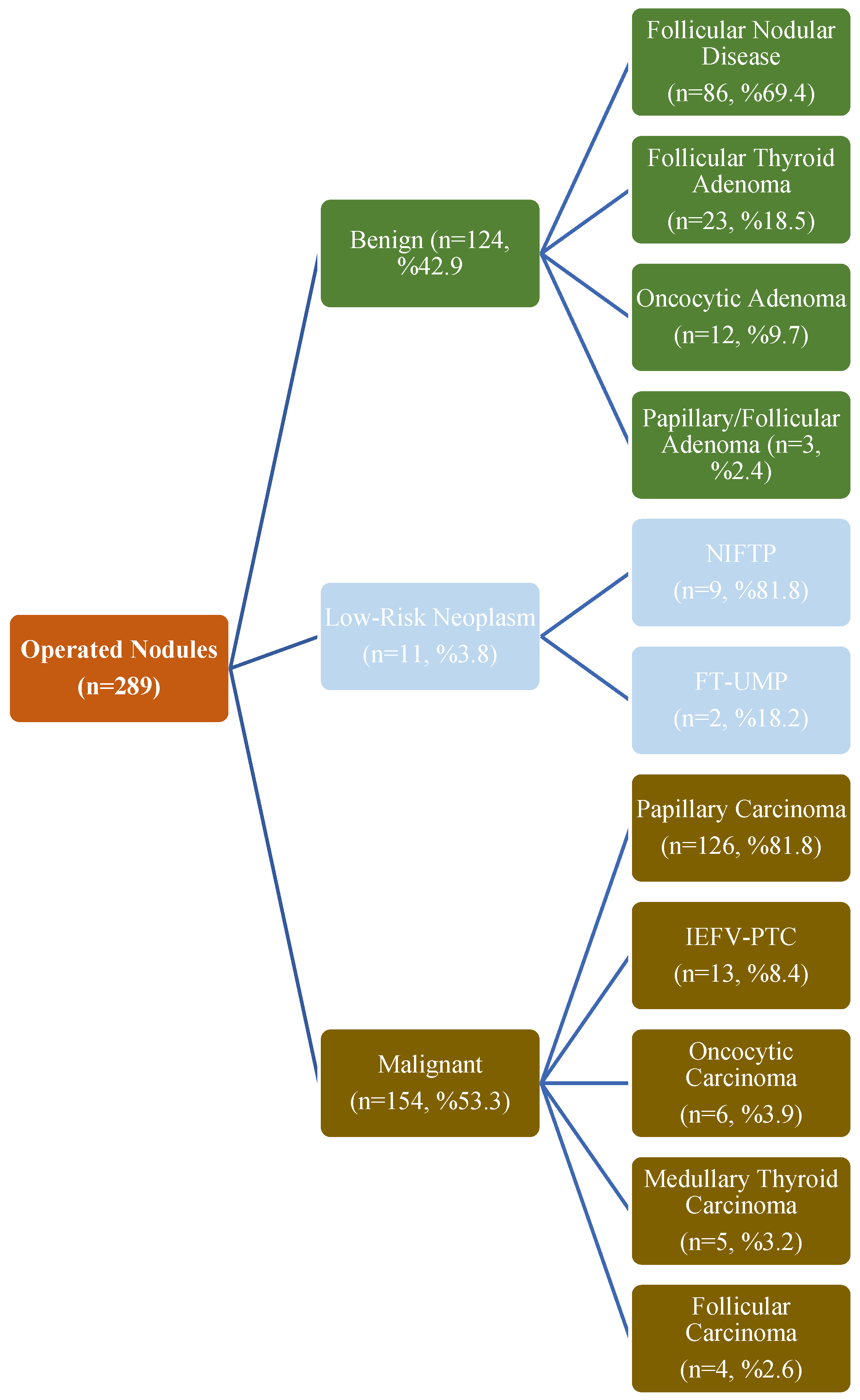

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics

3.2. Comparison of Benign and Malignant Nodules Based on Histopathology

3.3. Correlation Between the EU-TIRADS Classification and the Bethesda Classification

3.4. Multivariate Analyses of Sonographic Features Associated with Malignancy Risk

3.5. Diagnostic Performance in Operated Nodules

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FNAB | fine-needle aspiration biopsy |

| BMI | body mass index |

| AUS | atypia of undetermined significance |

| IEFV-PTC | invasive encapsulated follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinoma |

| DHGTC | differentiated high-grade thyroid carcinoma |

| PDTC | poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma |

| NIFTP | non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features |

| FT-UMP | follicular tumor of uncertain malignant potential |

| WD-UMP | well-differentiated tumor of uncertain malignant potential |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| CI | confidence interval |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| NPV | negative predictive value |

| OR | odds ratio |

| EU-TIRADS | European Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| ACR-TIRADS | American College of Radiology Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| C-TIRADS | Chinese Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| ATA | American Thyroid Association |

| TSH | thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- Solbiati, L.; Osti, V.; Cova, L.; Tonolini, M. Ultrasound of thyroid, parathyroid glands and neck lymph nodes. Eur. Radiol. 2001, 11, 2411–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, M.T.; Gilbert, C.; Ohori, N.P.; Tublin, M.E. Correlation of ultrasound findings with the Bethesda cytopathology classification for thyroid nodule fine-needle aspiration: A primer for radiologists. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013, 201, W487–W494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Pacini, F.; Randolph, G.W.; Sawka, A.M.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.Z.; Baloch, Z.W.; Cochand-Priollet, B.; Schmitt, F.C.; Vielh, P.; VanderLaan, P.A. The 2023 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid 2023, 33, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, E.; Majlis, S.; Rossi, R.; Franco, C.; Niedmann, J.P.; Castro, A.; Dominguez, M. An ultrasonogram reporting system for thyroid nodules stratifying cancer risk for clinical management. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 1748–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessler, F.N.; Middleton, W.D.; Grant, E.G.; Hoang, J.K.; Berland, L.L.; Teefey, S.A.; Cronan, J.J.; Beland, M.D.; Desser, T.S.; Frates, M.C.; et al. ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS): White Paper of the ACR TI-RADS Committee. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2017, 14, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, G.; Bonnema, S.J.; Erdogan, M.F.; Durante, C.; Ngu, R.; Leenhardt, L. European Thyroid Association Guidelines for Ultrasound Malignancy Risk Stratification of Thyroid Nodules in Adults: The EU-TIRADS. Eur. Thyroid J. 2017, 6, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kılınç Uğurlu, A.; Bitkay, A.; Gürbüz, F.; Karakuş, E.; Bayram Ilıkan, G.; Damar, Ç.; Şahin, S.; Kıran, M.M.; Gülaldi, N.; Azılı, M.N.; et al. Evaluating Postoperative Outcomes and Investigating the Usefulness of EU-TIRADS Scoring in Managing Pediatric Thyroid Nodules Bethesda 3 and 4. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2024, 16, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeste Fernández, D.; Vega Amenabar, E.; Coma Muñoz, A.; Arciniegas Vallejo, L.; Clemente León, M.; Planes-Conangla, M.; Felip, C.I.; Álvarez, C.S.; Burrieza, G.G.; Campos-Martorell, A. Ultrasound criteria (EU-TIRADS) to identify thyroid nodule malignancy risk in adolescents. Correlation with cyto-histological findings. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2021, 68, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, S.; Balci, I.G.; Tomak, L. Diagnostic Performance of Thyroid Nodule Risk Stratification Systems: Comparison of ACR-TIRADS, EU-TIRADS, K-TIRADS, and ATA Guidelines. Ultrasound Q. 2023, 39, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.; Ming, X.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yao, M.; Ni, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Mapping global epidemiology of thyroid nodules among general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1029926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, H.; Papini, E.; Paschke, R.; Duick, D.S.; Valcavi, R.; Hegedüs, L.; Vitti, P.; Balafouta, S.T.; Baloch, Z.; Crescenzi, A.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules: Executive summary of recommendations. Endocr. Pract. 2010, 16, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mazzaferri, E.L. Management of a solitary thyroid nodule. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Welker, M.J.; Orlov, D. Thyroid nodules. Am. Fam. Physician. 2003, 67, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Huo, L.; Huang, Y.; Jin, X.; Deng, J.; Zhu, S.; Jin, W.; Zhang, S.; et al. The association of thyroid nodule with non-iodized salt among Chinese children. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102726. [Google Scholar]

- Guth, S.; Theune, U.; Aberle, J.; Galach, A.; Bamberger, C.M. Very high prevalence of thyroid nodules detected by high frequency (13 MHz) ultrasound examination. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 39, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, N.; Medici, M.; Angell, T.E.; Liu, X.; Marqusee, E.; Cibas, E.S.; Krane, J.F.; Barletta, J.A.; Kim, M.I.; Larsen, P.R.; et al. The Influence of Patient Age on Thyroid Nodule Formation, Multinodularity, and Thyroid Cancer Risk. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 4434–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaraifi, A.K.; Alessa, M.; Hijazi, L.O.; Alayed, A.M.; Alsalem, A.A. TSH level as a risk factor of thyroid malignancy for nodules in euthyroid patients. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2023, 43, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D.H.; Song, K.; Kwon, H.; Bae, D.S.; Kim, J.-H.; Min, H.S.; Lee, K.E.; Youn, Y.-K. Does Tumor Size Influence the Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology for Thyroid Nodules? Int. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 2016, 3803647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, K.L.; Jabbour, N.; Ogilvie, J.B.; Ohori, N.P.; Carty, S.E.; Yim, J.H. The incidence of cancer and rate of false-negative cytology in thyroid nodules greater than or equal to 4 cm in size. Surgery 2007, 142, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, R.; Murphy, M.; McCarthy, J.; O’Leary, G.; Tuthill, A.; Murphy, M.S.; Sheahan, P. False negatives in thyroid cytology: Impact of large nodule size and follicular variant of papillary carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2013, 123, 1305–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, S.C.; Marqusee, E.; Kim, M.I.; Frates, M.C.; Ritner, J.; Peters, H.; Benson, C.B.; Doubilet, P.M.; Cibas, E.S.; Barletta, J.; et al. Thyroid nodule size and prediction of cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magister, M.J.; Chaikhoutdinov, I.; Schaefer, E.; Williams, N.; Saunders, B.; Goldenberg, D. Association of Thyroid Nodule Size and Bethesda Class With Rate of Malignant Disease. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 141, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M.; Crothers, B.A.; Burch, H.B. The impact of thyroid nodule size on the risk of malignancy and accuracy of fine-needle aspiration: A 10-year study from a single institution. Thyroid 2012, 22, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucler, R.; Usluogulları, C.A.; Tam, A.A.; Ozdemir, D.; Balkan, F.; Yalcın, S.; Kıyak, G.; Ersoy, P.E.; Guler, G.; Ersoy, R.; et al. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy for thyroid nodules three centimeters or larger in size. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2015, 43, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A.; Johnson, D.N.; White, M.G.; Siddiqui, S.; Antic, T.; Mathew, M.; Grogan, R.H.; Angelos, P.; Kaplan, E.L.; Cipriani, N.A. Thyroid Nodule Size at Ultrasound as a Predictor of Malignancy and Final Pathologic Size. Thyroid 2017, 27, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, A.U.; Ehsan, M.; Javed, H.; Ameer, M.Z.; Mohsin, A.; Rehman, M.A.U.; Nawaz, A.; Amjad, Z.; Ameer, F. Solitary and multiple thyroid nodules as predictors of malignancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid Res. 2022, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageeli, R.S.; Mossery, R.A.; Othathi, R.J.; Khawaji, E.A.; Tarshi, M.M.; Khormi, G.J.; Bingasem, S.M.; A Khmees, R.; Aburasain, N.S.; Al Ghadeeb, M. The Importance of the Thyroid Nodule Location in Determining the Risk of Malignancy: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2022, 14, e29421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herh, S.J.; Kim, E.K.; Sung, J.M.; Yoon, J.H.; Moon, H.J.; Kwak, J.Y. Heterogeneous echogenicity of the thyroid parenchyma does not influence the detection of multi-focality in papillary thyroid carcinoma on preoperative ultrasound staging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2014, 40, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Park, S.H.; Kim, E.-K.; Yoon, J.H.; Moon, H.J.; Lee, H.S.; Kwak, J.Y. Heterogeneous echogenicity of the underlying thyroid parenchyma: How does this affect the analysis of a thyroid nodule? BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, M.; Schott, M. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and papillary thyroid cancer: Are they immunologically linked? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.A. Clinical review: Clinical utility of thyroglobulin antibody (TgAb) measurements for patients with differentiated thyroid cancers (DTC). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 3615–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.; Handelsman, R.S.; Farrá, J.C.; Lew, J.I. Increased Incidental Thyroid Cancer in Patients With Subclinical Chronic Lymphocytic Thyroiditis. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 245, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, J.P.; Gionfriddo, M.R.; Al Nofal, A.; Boehmer, K.R.; Leppin, A.L.; Reading, C.; Callstrom, M.; Elraiyah, T.A.; Prokop, L.J.; Stan, M.N.; et al. The accuracy of thyroid nodule ultrasound to predict thyroid cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Na, D.G.; Yoon, S.J.; Gwon, H.Y.; Paik, W.; Kim, T.; Kim, J.Y. Ultrasound malignancy risk stratification of thyroid nodules based on the degree of hypoechogenicity and echotexture. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remonti, L.R.; Kramer, C.K.; Leitão, C.B.; Pinto, L.C.; Gross, J.L. Thyroid ultrasound features and risk of carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Thyroid 2015, 25, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grani, G.; Lamartina, L.; Ramundo, V.; Falcone, R.; Lomonaco, C.; Ciotti, L.; Barone, M.; Maranghi, M.; Cantisani, V.; Filetti, S.; et al. Taller-Than-Wide Shape: A New Definition Improves the Specificity of TIRADS Systems. Eur. Thyroid J. 2020, 9, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria Pantano, A.; Maddaloni, E.; Briganti, S.I.; Anguissola, G.B.; Perrella, E.; Taffon, C.; Palermo, A.; Pozzilli, P.; Manfrini, S.; Crescenzi, A. Differences between ATA, AACE/ACE/AME and ACR TI-RADS ultrasound classifications performance in identifying cytological high-risk thyroid nodules. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 178, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, W.D.; Teefey, S.A.; Reading, C.C.; Langer, J.E.; Beland, M.D.; Szabunio, M.M.; Desser, T.S. Multiinstitutional Analysis of Thyroid Nodule Risk Stratification Using the American College of Radiology Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 208, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.-J.; Jung, S.L.; Lee, J.H.; Na, D.G.; Baek, J.-H.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.S.; Byun, J.S.; Lee, D.H.; et al. Benign and malignant thyroid nodules: US differentiation--multicenter retrospective study. Radiology 2008, 247, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, D.G.; Baek, J.H.; Sung, J.Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, J.K.; Choi, Y.J.; Seo, H. Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System Risk Stratification of Thyroid Nodules: Categorization Based on Solidity and Echogenicity. Thyroid 2016, 26, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabahati, M.; Moazezi, Z. Performance of European Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System in Stratifying Malignancy Risk of Thyroid Nodules: A Prospective Study. J. Med. Ultrasound 2023, 31, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.Y.; Jung, I.; Baek, J.H.; Baek, S.M.; Choi, N.; Choi, Y.J.; Jung, S.L.; Kim, E.-K.; Kim, J.-A.; Kim, J.-H.; et al. Image reporting and characterization system for ultrasound features of thyroid nodules: Multicentric Korean retrospective study. Korean J. Radiol. 2013, 14, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsal, O.; Akpinar, M.; Turk, B.; Ucak, I.; Ozel, A.; Kayaoglu, S.; Coskun, B.U. Sonographic scoring of solid thyroid nodules: Effects of nodule size and suspicious cervical lymph node. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 83, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.S.; Kim, E.K.; Kang, D.R.; Lim, S.K.; Kwak, J.Y.; Kim, M.J. Biopsy of thyroid nodules: Comparison of three sets of guidelines. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 194, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaslioğlu, A.; Erbil, Y.; Dural, C.; Işsever, H.; Kapran, Y.; Ozarmağan, S.; Tezelman, S. Predictive value of sonographic features in preoperative evaluation of malignant thyroid nodules in a multinodular goiter. World J. Surg. 2008, 32, 1948–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukasa-Kakamba, J.; Bayauli, P.; Sabbah, N.; Bidingija, J.; Atoot, A.; Mbunga, B.; Nkodila, A.; Atoot, A.; Bangolo, A.I.; M’bUyamba-Kabangu, J.R. Ultrasound performance using the EU-TIRADS score in the diagnosis of thyroid cancer in Congolese hospitals. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellana, M.; Grani, G.; Radzina, M.; Guerra, V.; Giovanella, L.; Deandrea, M.; Ngu, R.; Durante, C.; Trimboli, P. Performance of EU-TIRADS in malignancy risk stratification of thyroid nodules: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 183, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Li, C.; Chen, Z.; He, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. Diagnostic efficiency among Eu-/C-/ACR-TIRADS and S-Detect for thyroid nodules: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1227339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.P.; Antunes, C.; Caseiro-Alves, F.; Donato, P. Analysis of 665 thyroid nodules using both EU-TIRADS and ACR TI-RADS classification systems. Thyroid Res. 2023, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, P.K.; Mahajan, N.C. Fine needle aspiration cytology of thyroid swellings: How useful and accurate is it? Indian J. Cancer 2010, 47, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, Y.S.; Poon, C.M.; Mak, S.M.; Suen, M.W.; Leong, H.T. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of thyroid nodules—How well are we doing? Hong Kong Med. J. 2007, 13, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nandedkar, S.S.; Dixit, M.; Malukani, K.; Varma, A.V.; Gambhir, S. Evaluation of Thyroid Lesions by Fine-needle Aspiration Cytology According to Bethesda System and its Histopathological Correlation. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2018, 8, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Verma, N.; Kaushal, V.; Sharma, D.R.; Sharma, D. Diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration cytology of thyroid gland lesions: A study of 200 cases in Himalayan belt. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2017, 13, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Number (Percentage) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age * | 824 | 49.4 ± 12.3 |

| Gender | 824 | |

| Female | 661 (80.2) | |

| Male | 163 (19.8) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) * | 411 | 28.3 ± 5.3 |

| Hormonal status | 824 | |

| Hypothyroid | 101 (12.3) | |

| Euthyroid | 608 (73.8) | |

| Hyperthyroid | 115 (14.0) |

| Characteristic (n = 1132) | Number (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Nodule size (mm) * | 19.9 ± 12.6 |

| Number of nodules | |

| Single | 168 (14.8) |

| Multiple | 964 (85.2) |

| Nodule side | |

| Right | 533 (47.1) |

| Left | 492 (43.5) |

| Isthmus | 107 (9.5) |

| Nodule location (n = 1027) | |

| Upper | 171 (16.7) |

| Middle | 453 (44.1) |

| Lower | 403 (39.2) |

| Nodule distribution | |

| Unilateral | 282 (24.9) |

| Bilateral | 850 (75.1) |

| Presence of thyroiditis | 826 (73.0) |

| Parenchymal echogenicity | |

| Mildly heterogeneous | 458 (40.5) |

| Moderately heterogeneous | 142 (12.5) |

| Markedly heterogeneous | 59 (5.2) |

| Homogeneous | 473 (41.8) |

| Nodule composition | |

| Cystic/predominantly cystic | 15 (1.3) |

| Mixed | 129 (11.4) |

| Solid/predominantly solid | 988 (87.3) |

| Nodule echogenicity | |

| Anechoic | 37 (3.3) |

| Hypoechoic | 442 (39.0) |

| Isoechoic | 598 (52.8) |

| Hyperechoic | 4 (0.4) |

| Markedly hypoechoic | 51 (4.5) |

| Nodule shape | |

| Ovoid–regular | 1079 (95.3) |

| Taller than wide | 53 (4.7) |

| Nodule margins | |

| Regular | 974 (86.0) |

| Irregular | 158 (14.0) |

| Macrocalcification | 169 (14.9) |

| Microcalcification | 48 (4.2) |

| Linear microechogenicity | 91 (8.0) |

| Comet-tail artifact | 20 (1.8) |

| Bethesda (n = 1132) | Number (Percentage) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nondiagnostic | 87 (7.7) |

| 2 | Benign | 710 (62.7) |

| 3 | AUS | 176 (15.6) |

| 4A | Suspicious for follicular neoplasm | 13 (1.2) |

| 4B | Suspicious for oncocytic neoplasm | 5 (0.4) |

| 5 | Suspicious for malignancy | 58 (5.1) |

| 6A | Papillary carcinoma | 78 (6.9) |

| 6B | Medullary carcinoma | 5 (0.4) |

| Characteristic | Benign (n = 124) | Malignant (n = 154) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Nodule size (cm) * | 26.2 ± 15.7 | 16.7 ± 11.9 | <0.001 † |

| Number of nodules | <0.001 | ||

| Single | 10 (8.1) | 39 (25.3) | |

| Multiple | 114 (91.9) | 115 (74.7) | |

| Nodule side | 0.686 | ||

| Right | 58 (46.8) | 80 (51.9) | |

| Left | 52 (41.9) | 59 (38.3) | |

| Isthmus | 14 (11.3) | 15 (9.7) | |

| Nodule location | 0.047 | ||

| Upper | 19 (17.3) | 36 (25.9) | |

| Middle | 52 (47.3) | 72 (51.8) | |

| Lower | 39 (35.5) | 31 (22.3) | |

| Nodule distribution | 0.004 | ||

| Unilateral | 22 (17.7) | 51 (33.1) | |

| Bilateral | 102 (82.3) | 103 (66.9) | |

| Presence of thyroiditis | 95 (76.6) | 109 (70.8) | 0.274 |

| Parenchymal echogenicity | 0.872 | ||

| Mildly heterogeneous | 49 (39.5) | 64 (41.6) | |

| Moderately heterogeneous | 16 (12.9) | 15 (9.7) | |

| Markedly heterogeneous | 4 (3.2) | 5 (3.2) | |

| Homogeneous | 55 (44.4) | 70 (45.5) | |

| Nodule composition | 0.130 | ||

| Cystic/predominantly cystic | 2 (1.6) | 0 | |

| Mixed | 16 (12.9) | 13 (8.4) | |

| Solid/predominantly solid | 106 (85.5) | 141 (91.6) | |

| Nodule echogenicity | <0.001 | ||

| Anechoic | 4 (3.2) | 4 (2.6) | |

| Hypoechoic | 32 (25.8) | 103 (66.9) | |

| Isoechoic | 84 (67.7) | 37 (24.0) | |

| Hyperechoic | 0 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Markedly hypoechoic | 4 (3.2) | 9 (5.8) | |

| Nodule shape | 0.001 | ||

| Ovoid–regular | 122 (98.4) | 136 (88.3) | |

| Taller than wide | 2 (1.6) | 18 (11.7) | |

| Nodule margins | <0.001 | ||

| Regular | 116 (93.5) | 92 (59.7) | |

| Irregular | 8 (6.5) | 62 (40.3) | |

| Macrocalcification | 23 (18.5) | 34 (22.1) | 0.469 |

| Microcalcification | 2 (1.6) | 31 (20.1) | <0.001 |

| Linear microechogenicity | 12 (9.7) | 16 (10.4) | 0.845 |

| Comet-tail artifact | 3 (2.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0.218 |

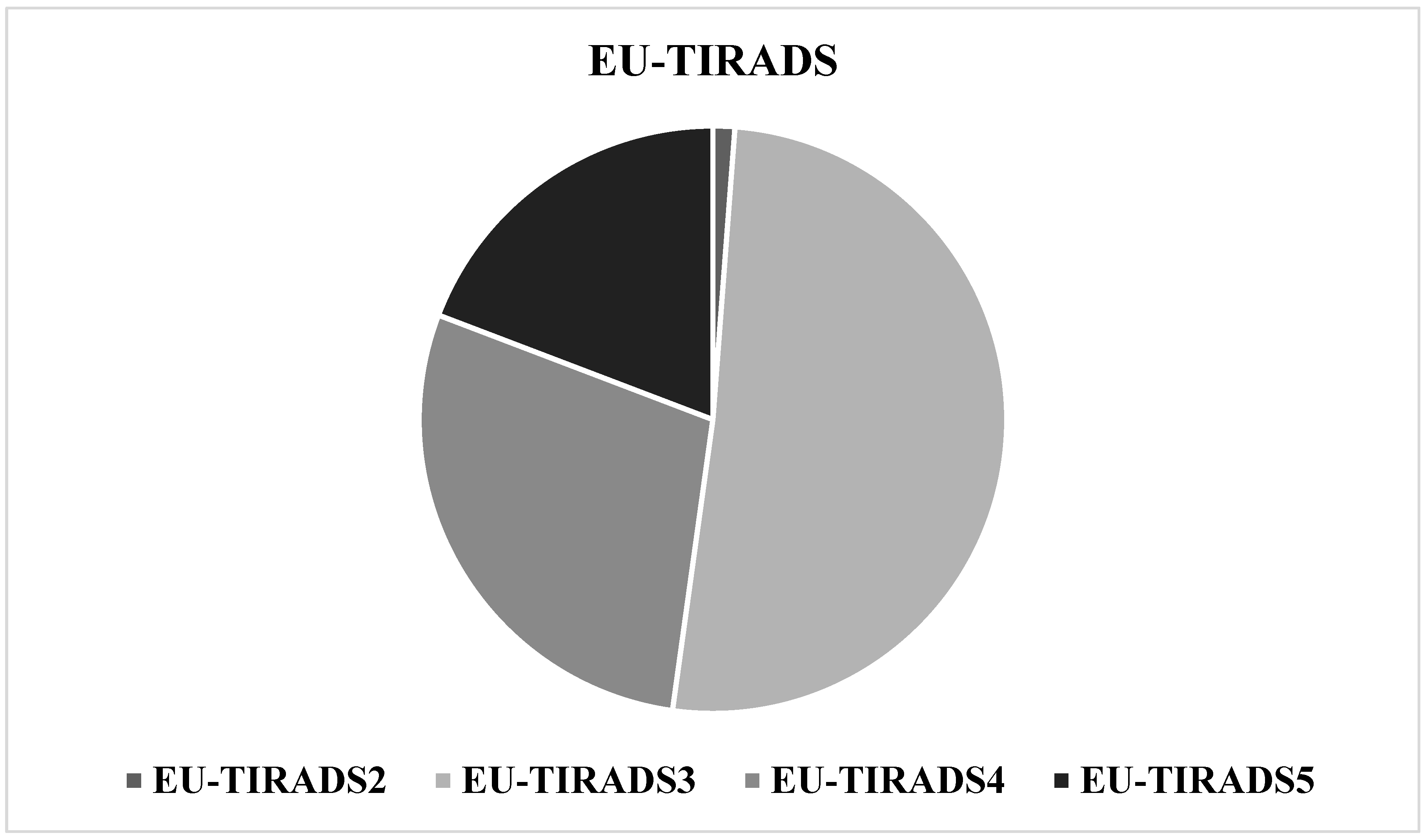

| Bethesda | Bethesda | Histopathology | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk Bethesda II–III | High Risk Bethesda IV, V–VI | Malignancy Risk | Malignancy Rate * | |

| N (%) | N (%) | % | % | |

| EU-TIRADS-II | 7 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EU-TIRADS-III | 527 (59.5) | 12 (7.5) | 2.2 | 4.3 |

| EU-TIRADS-IV | 252 (28.4) | 48 (30.2) | 16.0 | 14.5 |

| EU-TIRADS-V | 100 (11.3) | 99 (62.3) | 49.7 | 37.8 |

| Univariate Analyses | Multivariate Analyses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | %95 CI | p Value | OR | %95 CI | p Value | |

| Markedly hypoechoic appearance | 1.38 | 0.65–2.90 | 0.391 | 0.41 | 0.09–1.84 | 0.245 |

| Taller than wide | 3.56 | 1.96–6.47 | <0.001 | 4.70 | 0.97–22.83 | 0.055 |

| Irregular margins | 6.19 | 4.21–9.09 | <0.001 | 8.15 | 3.36–19.76 | <0.001 |

| Microcalcification | 14.24 | 7.66–26.50 | <0.001 | 10.01 | 2.20–45.43 | 0.003 |

| AUC | %95 CI | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markedly hypoechoic appearance | 0.508 | 0.478–0.537 | 0.439 | |||

| Taller than wide | 0.541 | 0.511–0.570 | 0.002 | |||

| Irregular margins | 0.652 | 0.624–0.680 | <0.001 | |||

| Microcalcification | 0.592 | 0.563–0.621 | <0.001 | |||

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |||

| Markedly hypoechoic appearance | 5.8 | 95.7 | 17.6 | 86.6 | ||

| Taller than wide | 11.6 | 96.4 | 34.0 | 87.4 | ||

| Irregular margins | 40.2 | 90.1 | 39.2 | 90.6 | ||

| Microcalcification | 20.1 | 98.2 | 64.6 | 88.7 | ||

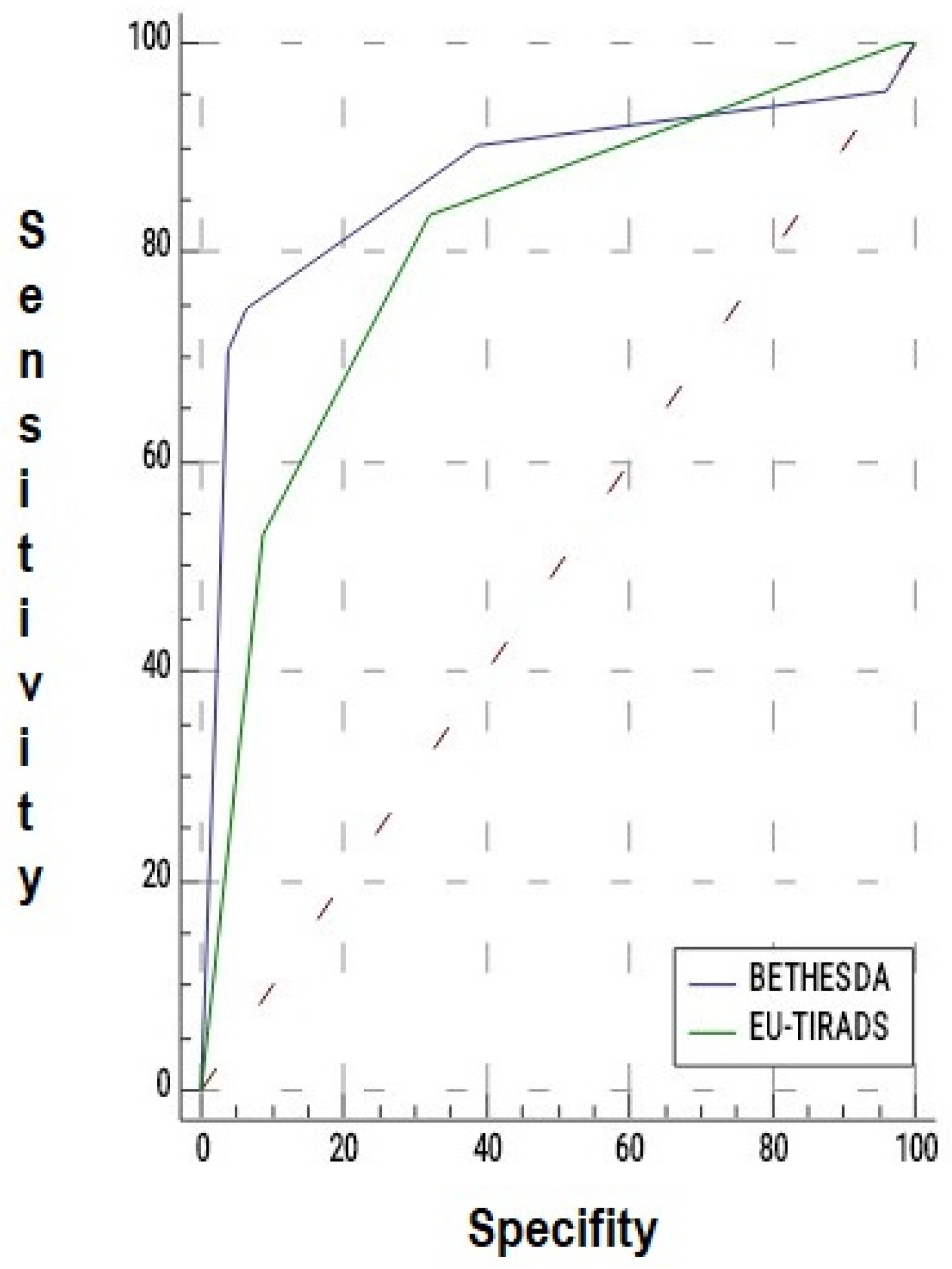

| AUC | %95 CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EU-TIRADS | 0.808 | 0.756–0.852 | <0.001 |

| Bethesda | 0.869 | 0.823–0.906 | <0.001 |

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU-TIRADS (>III) | ||||

| >II | 100.0 | 1.6 | 55.8 | 100.0 |

| >III | 83.7 | 67.7 | 71.2 | 77.7 |

| >IV | 53.2 | 91.1 | 80.6 | 61.1 |

| >V | 0 | 100.0 | - | 44.6 |

| Bethesda (>III) | ||||

| >I | 95.4 | 4.0 | 55.3 | 41.7 |

| >II | 90.2 | 61.2 | 74.3 | 83.5 |

| >III | 74.6 | 93.5 | 93.5 | 74.8 |

| >IV | 70.7 | 95.9 | 95.6 | 72.6 |

| >V | 42.2 | 97.5 | 95.6 | 57.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çimen, Ş.; Zeybek, N.; Bahçecioğlu, A.B.; Yılmaz, K.B.; Gülçelik, N.E.; Gülçelik, M.A. Microcalcification and Irregular Margins as Key Predictors of Thyroid Cancer: Integrated Analysis of EU-TIRADS, Bethesda, and Histopathology. Medicina 2025, 61, 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122217

Çimen Ş, Zeybek N, Bahçecioğlu AB, Yılmaz KB, Gülçelik NE, Gülçelik MA. Microcalcification and Irregular Margins as Key Predictors of Thyroid Cancer: Integrated Analysis of EU-TIRADS, Bethesda, and Histopathology. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122217

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇimen, Şebnem, Nazif Zeybek, Adile Begüm Bahçecioğlu, Kerim Bora Yılmaz, Neşe Ersöz Gülçelik, and Mehmet Ali Gülçelik. 2025. "Microcalcification and Irregular Margins as Key Predictors of Thyroid Cancer: Integrated Analysis of EU-TIRADS, Bethesda, and Histopathology" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122217

APA StyleÇimen, Ş., Zeybek, N., Bahçecioğlu, A. B., Yılmaz, K. B., Gülçelik, N. E., & Gülçelik, M. A. (2025). Microcalcification and Irregular Margins as Key Predictors of Thyroid Cancer: Integrated Analysis of EU-TIRADS, Bethesda, and Histopathology. Medicina, 61(12), 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122217