Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome Severity on Heart Rate Variability and QTc Interval in Hypertensive Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

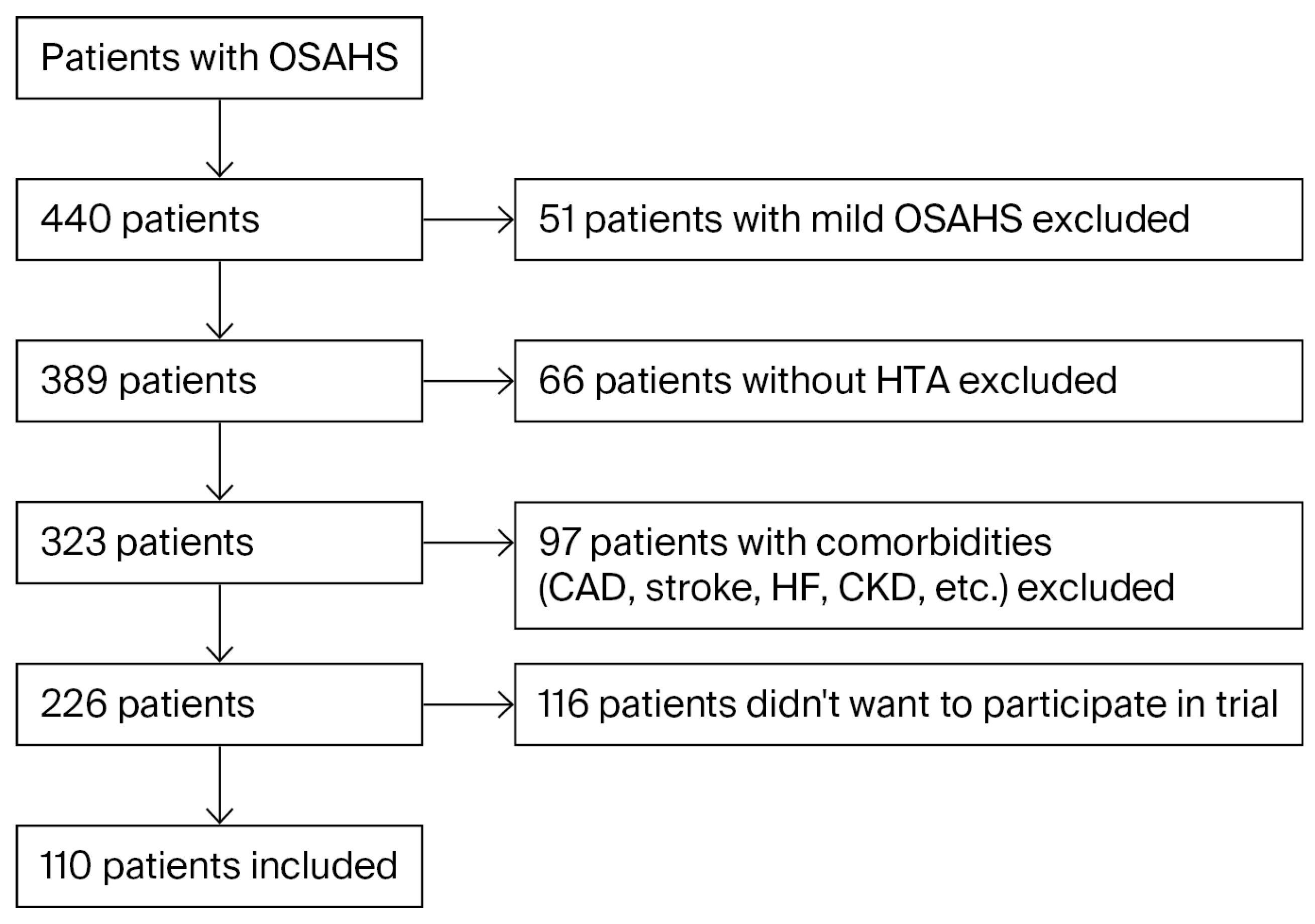

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Parameters of Holter ECG

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Strengths of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berry, R.B.; Budhiraja, R.; Gottlieb, D.J.; Gozal, D.; Iber, C.; Kapur, V.K.; Marcus, C.L.; Mehra, R.; Parthasarathy, S.; Quan, S.F.; et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: Update of the 2007 AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 597–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Lu, Y. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and metabolic diseases. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 2670–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouloukaki, I.; Fanaridis, M.; Stathakis, G.; Ermidou, C.; Kallergis, E.; Moniaki, V.; Mauroudi, E.; Schiza, S.E. Characteristics of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea at High Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. Medicina 2021, 57, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.E.; Ren, J. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular diseases. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2022, 54, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.A.; Ismail, H. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 37, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeghiazarians, Y.; Jneid, H.; Tietjens, J.R.; Redline, S.; Brown, D.L.; El-Sherif, N.; Mehra, R.; Bozkurt, B.; Ndumele, C.E.; Somers, V.K. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, e56–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, D.J.; Punjabi, N.M. Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea: A review. JAMA 2020, 323, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhu, R.; Tian, Y.; Wang, K. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with the risk of vascular outcomes and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research. Wake Up America: A National Sleep Alert; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- Young, T.; Finn, L.; Peppard, P.E.; Szklo-Coxe, M.; Austin, D.; Nieto, F.J.; Stubbs, R.; Hla, K.M. Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: Eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Sleep 2008, 31, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Parish, J.M.; Somers, V.K. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2004, 79, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gami, A.S.; Olson, E.J.; Shen, W.K.; Wright, R.S.; Ballman, K.V.; Hodge, D.O.; Herges, R.M.; Howard, D.E.; Somers, V.K. Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of sudden cardiac death: A longitudinal study of 10,701 adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuzzaman, A.; Amin, R.S.; van der Walt, C.; Davison, D.E.; Okcay, A.; Pressman, G.S.; Somers, V.K. Daytime cardiac repolarization in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2015, 19, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, J.N.; Walker, M.; Stafford, P.; Estrada, S.; Adabag, S.; Kwon, Y. Sleep apnea and sudden cardiac death. Circ. Rep. 2019, 1, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groffen, A.J.; Bikker, H.; Christiaans, I. Long QT syndrome overview. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Robison, L.B.; Brady, W.J.; Robison, R.A.; Charlton, N. QT interval prolongation and the risk of malignant ventricular dysrhythmia and/or cardiac arrest: Systematic search and narrative review of risk related to the magnitude of QT interval length. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 49, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsuzzaman, A.S.; Somers, V.K.; Knilans, T.K.; Ackerman, M.J.; Wang, Y.; Amin, R.S. Obstructive sleep apnea in patients with congenital long QT syndrome: Implications for increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Sleep 2015, 38, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, C.; Pengo, M.F.; Parati, G. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and autonomic dysfunction. Auton. Neurosci. 2019, 221, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, B.; Dalla Vecchia, L.A.; Porta, A.; La Rovere, M.T. Autonomic dysfunction and heart rate variability with Holter monitoring: A diagnostic look at autonomic regulation. Herzschrittmacherther. Elektrophysiol. 2021, 32, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, F.; Xiao, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Yi, Y.; Min, W.; Su, L.; Liu, X.; et al. Heart rate variability changes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarecka-Dobroń, A.; Braksator, W.; Chrom, P. QT variability and myocardial repolarization in sleep apnea: Implications for cardiac risk. Adv. Med. Sci. 2025, 70, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, V.K.; Auckley, D.H.; Chowdhuri, S.; Kuhlmann, D.C.; Mehra, R.; Ramar, K.; Harrod, C.G. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, J.S.; Varma, N.; Cygankiewicz, I.; Aziz, P.; Balsam, P.; Baranchuk, A.; Cantillon, D.J.; Dilaveris, P.; Dubner, S.J.; El-Sherif, N.; et al. 2017 ISHNE-HRS expert consensus statement on ambulatory ECG and external cardiac monitoring/telemetry. Heart Rhythm. 2017, 14, e55–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Thomas, B.L.; Claassen, N.; Becker, P.; Viljoen, M. Validity of commonly used heart rate variability markers of autonomic nervous system function. Neuropsychobiology 2019, 78, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Whitsel, E.A.; Folsom, A.R. Heart rate variability and lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 619–625.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, H.C.D.; Philbois, S.V.; Veiga, A.C.; Aguilar, B.A. Heart rate variability and cardiovascular fitness: What we know so far. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, A.M.; Ilie, A.C.; Ștefăniu, R.; Țăranu, S.M.; Sandu, I.A.; Alexa-Stratulat, T.; Pîslaru, A.I.; Alexa, I.D. The impact of heart rate variability monitoring on preventing severe cardiovascular events. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbacher, S.; Bossard, M.; von Rotz, M.; Schoen, T.; Maseli, A.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Leuppi, J.; Risch, M.; Risch, L.; et al. Sleep related breathing disorders and heart rate variability in young and healthy adults from the general population. Circulation 2015, 132, A17063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, V.C.C.; Bandeira, P.M.; Azevedo, J.C.M. Heart rate variability in adults with obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review. Sleep Sci. 2019, 12, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozal, D.; Hakim, F.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L. Chemoreceptors, baroreceptors, and autonomic deregulation in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2013, 185, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Altin, R.; Ozeren, A.; Kart, L.; Bilge, M.; Unalacak, M. Cardiac autonomic activity in obstructive sleep apnea: Time-dependent and spectral analysis of heart rate variability using 24-h Holter electrocardiograms. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2004, 31, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Guilleminault, C.; Connolly, S.; Winkle, R.; Melvin, K.; Tilkian, A. Cyclical variation of the heart rate in sleep apnoea syndrome. Mechanisms, and usefulness of 24 h electrocardiography as a screening technique. Lancet 1984, 1, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Watanabe, E.; Saito, Y.; Sasaki, F.; Fujimoto, K.; Nomiyama, T.; Kawai, K.; Kodama, I.; Sakakibara, H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea by cyclic variation of heart rate. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2011, 4, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Yuda, E. Night-to-night variability of sleep apnea detected by cyclic variation of heart rate during long-term continuous ECG monitoring. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022, 27, e12901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, T.; Yoshihisa, A.; Iwaya, S.; Abe, S.; Sato, T.; Suzuki, S.; Yamaki, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Kunii, H.; Nakazato, K.; et al. Cyclic variation in heart rate score by holter electrocardiogram as screening for sleep-disordered breathing in subjects with heart failure. Respir. Care 2015, 60, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayano, J.; Ueda, N.; Kisohara, M.; Yuda, E.; Watanabe, E.; Carney, R.M.; Blumenthal, J.A. Risk stratification after acute myocardial infarction by amplitude-frequency mapping of cyclic variation of heart rate. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2021, 26, e12825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgoifo, A.; Carnevali, L.; Alfonso Mde, L.; Amore, M. Autonomic dysfunction and heart rate variability in depression. Stress 2015, 18, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbacher, S.; Bossard, M.; Schoen, T.; Schmidlin, D.; Muff, C.; Maseli, A.; Leuppi, J.D.; Miedinger, D.; Probst-Hensch, N.M.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; et al. Heart Rate Variability and Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders in the General Population. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 118, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Ayappa, I.; Ayas, N.; Collop, N.; Kirsch, D.; McArdle, N.; Mehra, R.; Pack, A.I.; Punjabi, N.; White, D.P.; et al. Metrics of sleep apnea severity: Beyond the apnea-hypopnea index. Sleep 2021, 44, zsab030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkiewicz, K.; Montano, N.; Cogliati, C.; van de Borne, P.J.; Dyken, M.E.; Somers, V.K. Altered cardiovascular variability in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 1998, 98, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, A.; Clay, R.; Kumbam, A.; Tereshchenko, L.G.; Khan, A. A systematic review of the association between obstructive sleep apnea and ventricular arrhythmias. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2014, 10, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, A.; Niță, C.; Bala, C.; Hancu, N. Effect of sleep apnea syndrome on QT dispersion and QT corrected interval in patients with type 2 diabetes. Rom. J. Diabetes Nutr. Metab. Dis. 2011, 18, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi Jazi, M.; Amra, B.; Miadi, K.; Jahangiri, M.; Gholamrezaei, A.; Tabesh, F.; Yazdchi, M.R. QT Interval Variability in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2018, 26, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AHI 15–29.9 | AHI ≥ 30 | p 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.05 ± 8.76 | 53.49 ± 9.39 | 0.763 | ||

| Gender n (%) | |||||

| Male | 27 | 73.0 | 60 | 82.2 | 0.381 2 |

| Female | 10 | 27.0 | 13 | 17.8 | |

| Weight (kg) | 106.61 ± 19.68 | 113.86 ± 16.70 | 0.063 | ||

| Height (cm) | 175.72 ± 11.01 | 176.67 ± 7.83 | 0.648 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 119.44 ± 14.64 | 122.96 ± 12.15 | 0.190 | ||

| Neck circumference (cm) | 44.14 ± 4.07 | 46.25 ± 3.63 | 0.008 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 34.54 ± 5.95 | 36.68 ± 5.17 | 0.069 | ||

| AHI 15–29.9 | AHI ≥ 30 | p 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Smoking | 21 | 56.8 | 37 | 50.7 | 0.689 |

| Physical inactivity | 13 | 35.1 | 34 | 46.6 | 0.346 |

| Obesity | 29 | 78.4 | 67 | 93.1 | 0.033 2 |

| Stress | 12 | 32.4 | 15 | 20.5 | 0.257 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 | 16.2 | 25 | 34.2 | 0.072 |

| Heredity | 24 | 64.9 | 41 | 56.2 | 0.502 |

| Dyslipidemia | 28 | 75.7 | 48 | 65.8 | 0.398 |

| Number of risk factors (Median, IQR) | 4 | 3–8 | 5 | 4–6 | 0.697 2 |

| AHI 15–29.9 | AHI ≥ 30 | p 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Minimal HR † | 54.76 ± 8.47 | 53.97 ± 7.67 | 0.628 | ||

| Maximal HR † | 112.57 ± 15.72 | 113.25 ± 15.98 | 0.833 | ||

| Average HR † | 72.35 ± 10.67 | 71.63 ± 10.32 | 0.733 | ||

| Pauses | 3 | 8.1 | 5 | 6.8 | 1.000 2 |

| Bradycardia | 6 | 16.2 | 18 | 24.7 | 0.442 2 |

| SDNN † | 129.52 ± 36.12 | 130.2 ± 33.94 | 0.674 1 | ||

| SDNN > 100 ms | 31 | 83.8 | 54 | 83.1 | 1.000 2 |

| RMSD † | 50.31 ± 31.3 | 44.43 ± 18.64 | 0.736 1 | ||

| SDSD † | 42.01 ± 27.92 | 36.32 ± 16.06 | 0.689 1 | ||

| SDNNi † | 44.62 ± 15.83 | 43.63 ± 14.05 | 0.571 1 | ||

| SDNNi > 40 ms | 20 | 58.8 | 37 | 58.7 | 1.000 2 |

| SDANN † | 113.3 ± 35.41 | 121.57 ± 32.21 | 0.067 1 | ||

| SDANN > 100 ms | 23 | 62.2 | 48 | 72.7 | 0.374 2 |

| RR † | 857.66 ± 128.6 | 868.81 ± 115.69 | 0.567 1 | ||

| QT † | 417.09 ± 92.83 | 397.4 ± 24.7 | 0.339 3 | ||

| QTc † | 413.76 ± 34.6 | 409.46 ± 29.68 | 0.688 3 | ||

| TAMP † | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 0.569 3 | ||

| Parameters | SDNN | QTc | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apnea–hypopnea index | r | −0.057 | −0.076 |

| p | 0.594 | 0.475 | |

| df | 88 | 88 | |

| Oxygen desaturation index per hour | r | −0.112 | 0.043 |

| p | 0.295 | 0.689 | |

| df | 88 | 88 | |

| Time spent with oxygen saturation below 90% | r | −0.282 | −0.159 |

| p | 0.007 | 0.135 | |

| df | 88 | 88 | |

| Minimal oxygen saturation | r | 0.006 | −0.098 |

| p | 0.953 | 0.356 | |

| df | 88 | 88 | |

| Average oxygen saturation | r | 0.321 | 0.144 |

| p | 0.002 | 0.176 | |

| df | 88 | 88 | |

| Control variables: obesity, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, beta blocker | |||

| Models | B | SE | Beta | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| (Constant) | 139.439 | 13.053 | 0.000 | |

| Obesity | 0.316 | 11.508 | 0.003 | 0.978 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8.644 | 7.757 | 0.111 | 0.268 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 17.481 | 8.966 | 0.195 | 0.054 |

| Beta blocker use | −19.495 | 7.875 | −0.240 | 0.015 |

| TST 90% | −0.376 | 0.122 | −0.309 | 0.003 |

| Dependent variable: SDNN. Adjusted R2 = 0.144 | ||||

| Model 2 | ||||

| (Constant) | −118.917 | 84.751 | 0.164 | |

| Obesity | 6.070 | 10.162 | 0.058 | 0.552 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7.068 | 7.550 | 0.091 | 0.352 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 13.439 | 8.488 | 0.157 | 0.117 |

| Beta blocker use | −21.245 | 7.721 | −0.261 | 0.007 |

| Average oxygen saturation | 2.732 | 0.887 | 0.300 | 0.003 |

| Dependent variable: SDNN. Adjusted R2 = 0.148 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stojanović, M.M.; Deljanin Ilić, M.; Ristić, L.; Stamenković, Z.; Koraćević, G.; Gojković, D.; Kostić, J. Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome Severity on Heart Rate Variability and QTc Interval in Hypertensive Patients. Medicina 2025, 61, 2221. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122221

Stojanović MM, Deljanin Ilić M, Ristić L, Stamenković Z, Koraćević G, Gojković D, Kostić J. Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome Severity on Heart Rate Variability and QTc Interval in Hypertensive Patients. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2221. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122221

Chicago/Turabian StyleStojanović, Milovan M., Marina Deljanin Ilić, Lidija Ristić, Zoran Stamenković, Goran Koraćević, Dejana Gojković, and Jovana Kostić. 2025. "Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome Severity on Heart Rate Variability and QTc Interval in Hypertensive Patients" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2221. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122221

APA StyleStojanović, M. M., Deljanin Ilić, M., Ristić, L., Stamenković, Z., Koraćević, G., Gojković, D., & Kostić, J. (2025). Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome Severity on Heart Rate Variability and QTc Interval in Hypertensive Patients. Medicina, 61(12), 2221. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122221