Diagnostic Accuracy of Non-Contrast CT for Acute Appendicitis in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

2.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Data Synthesis

3. Results

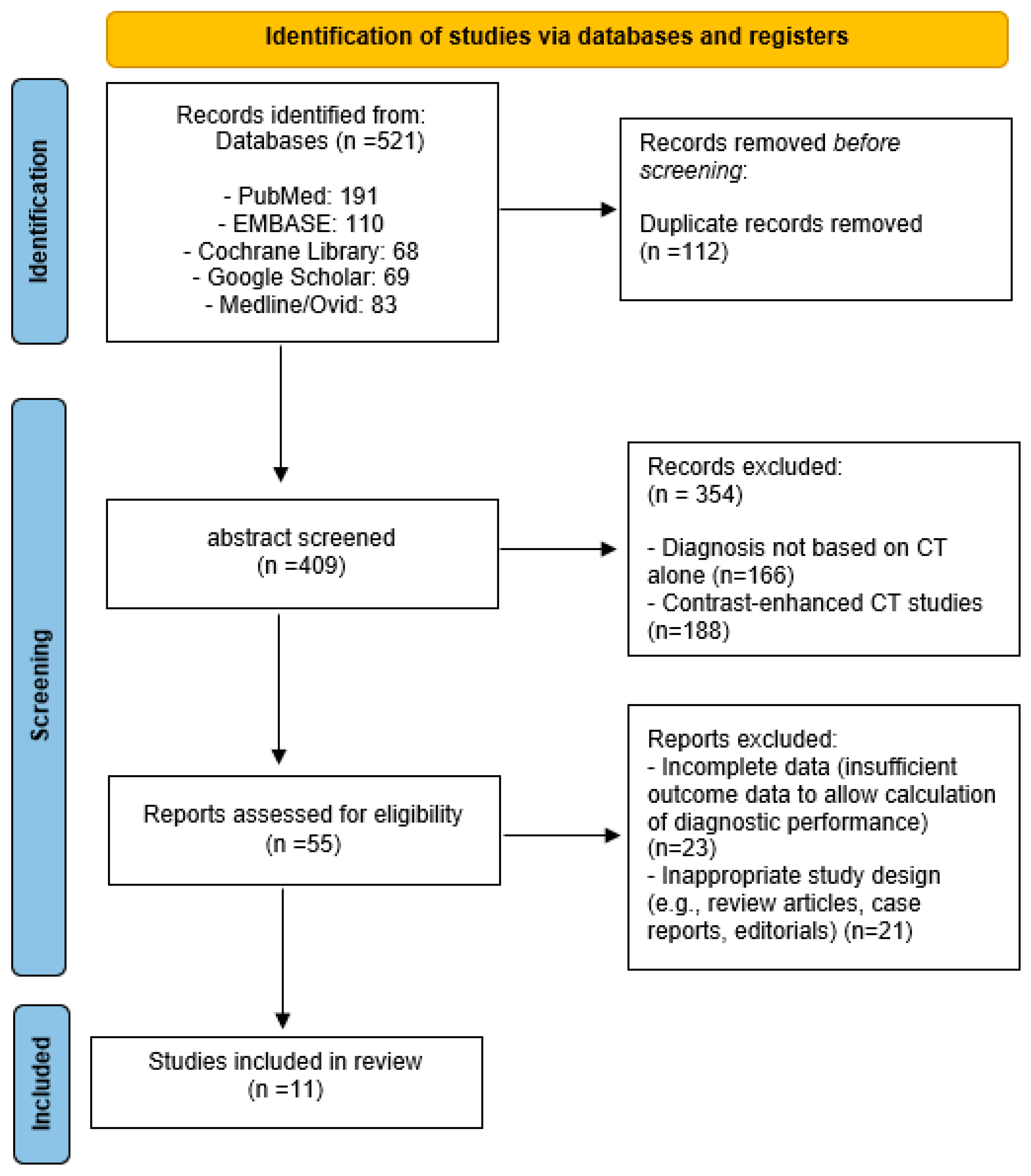

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection Flow

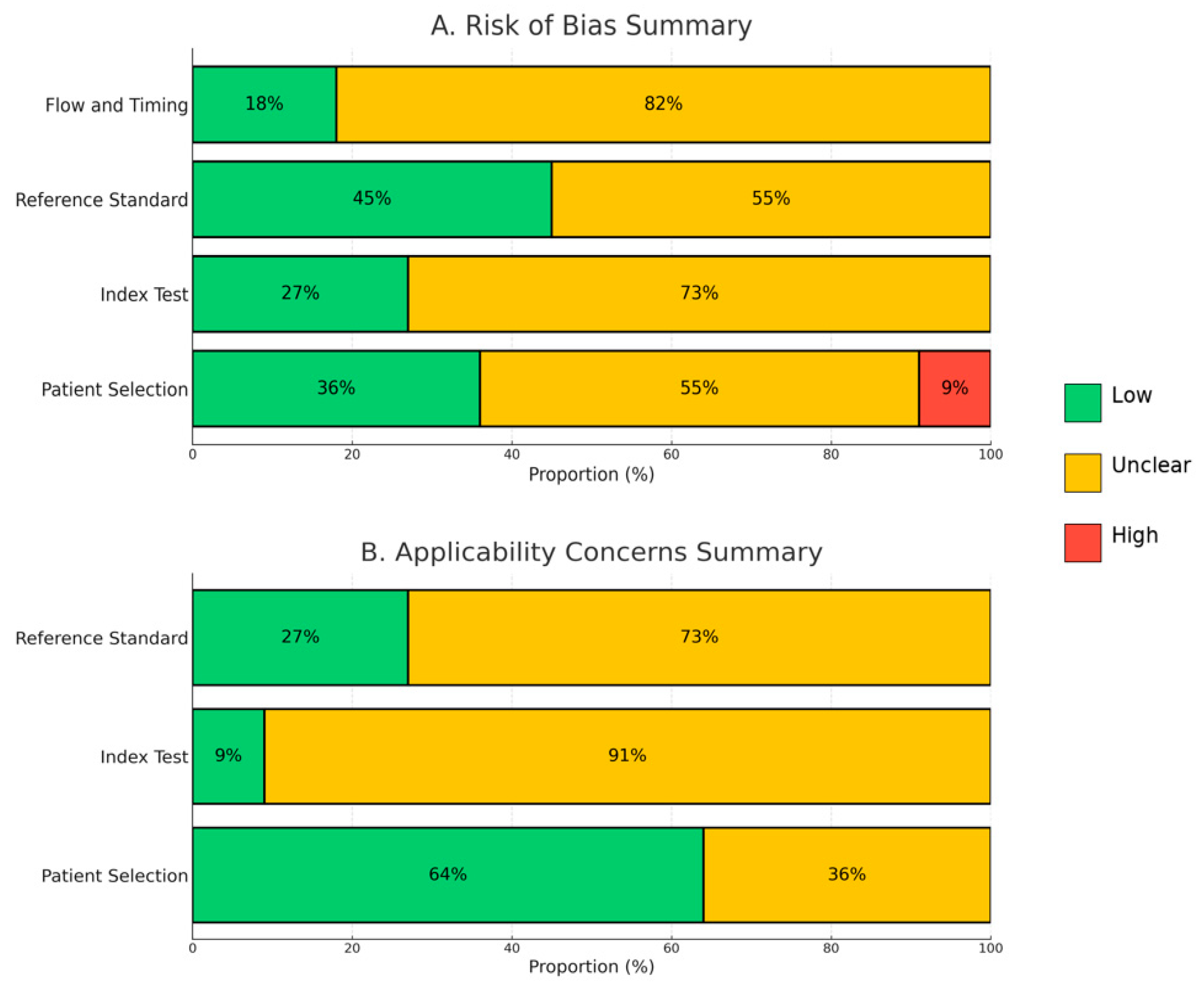

3.2. Assessment of Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias

3.3. Pooled Diagnostic Accuracy and Performance Analysis

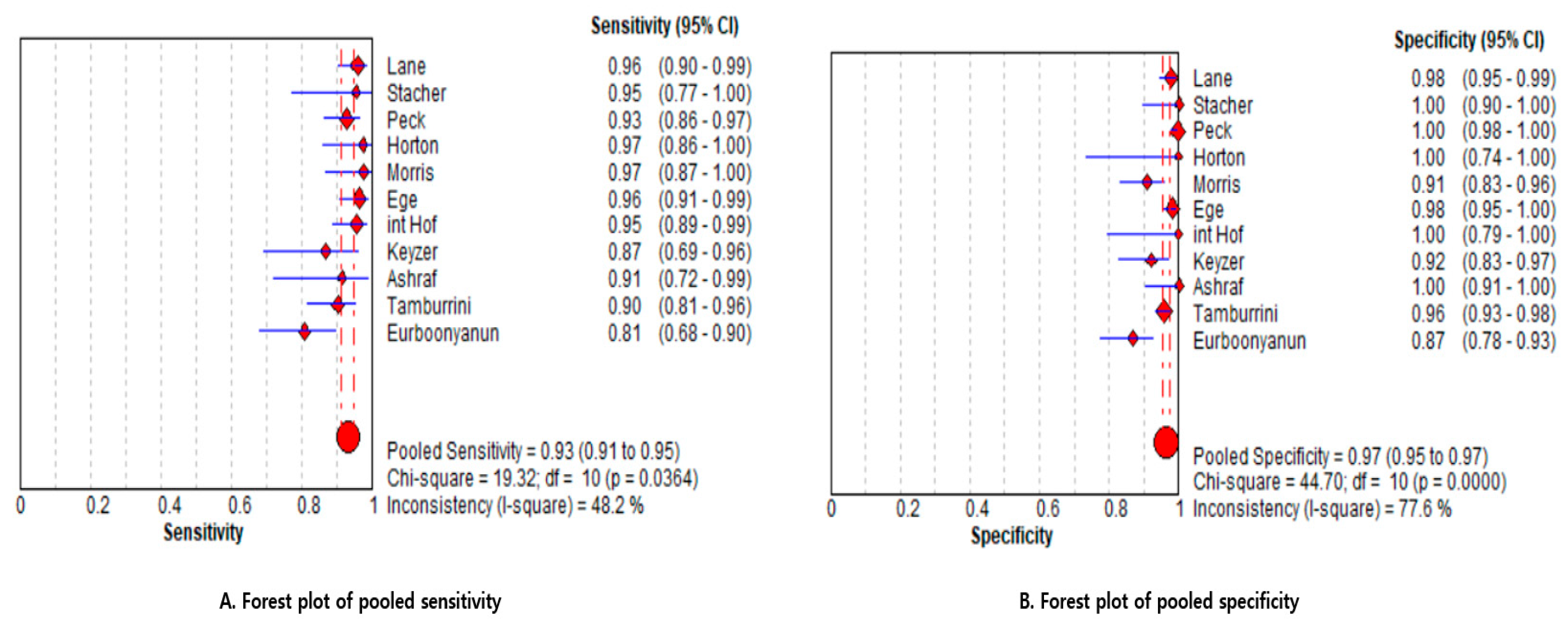

3.3.1. Pooled Estimates (Primary Analysis)

3.3.2. Sensitivity Analysis Based on Risk of Bias

3.3.3. Between-Study Heterogeneity

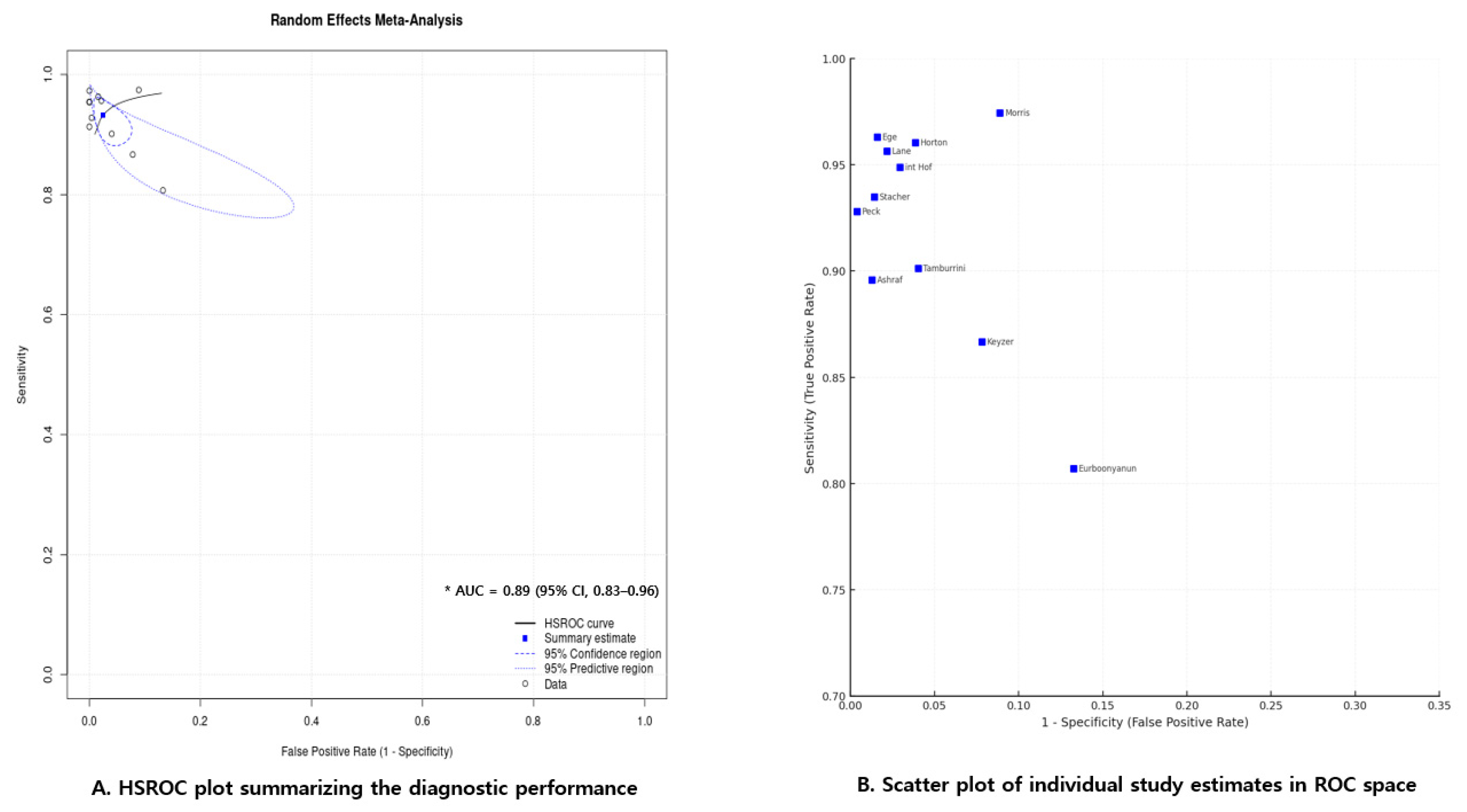

3.3.4. Summary ROC (HSROC) Model

3.3.5. Study-Level Distribution of Diagnostic Estimates in ROC Space

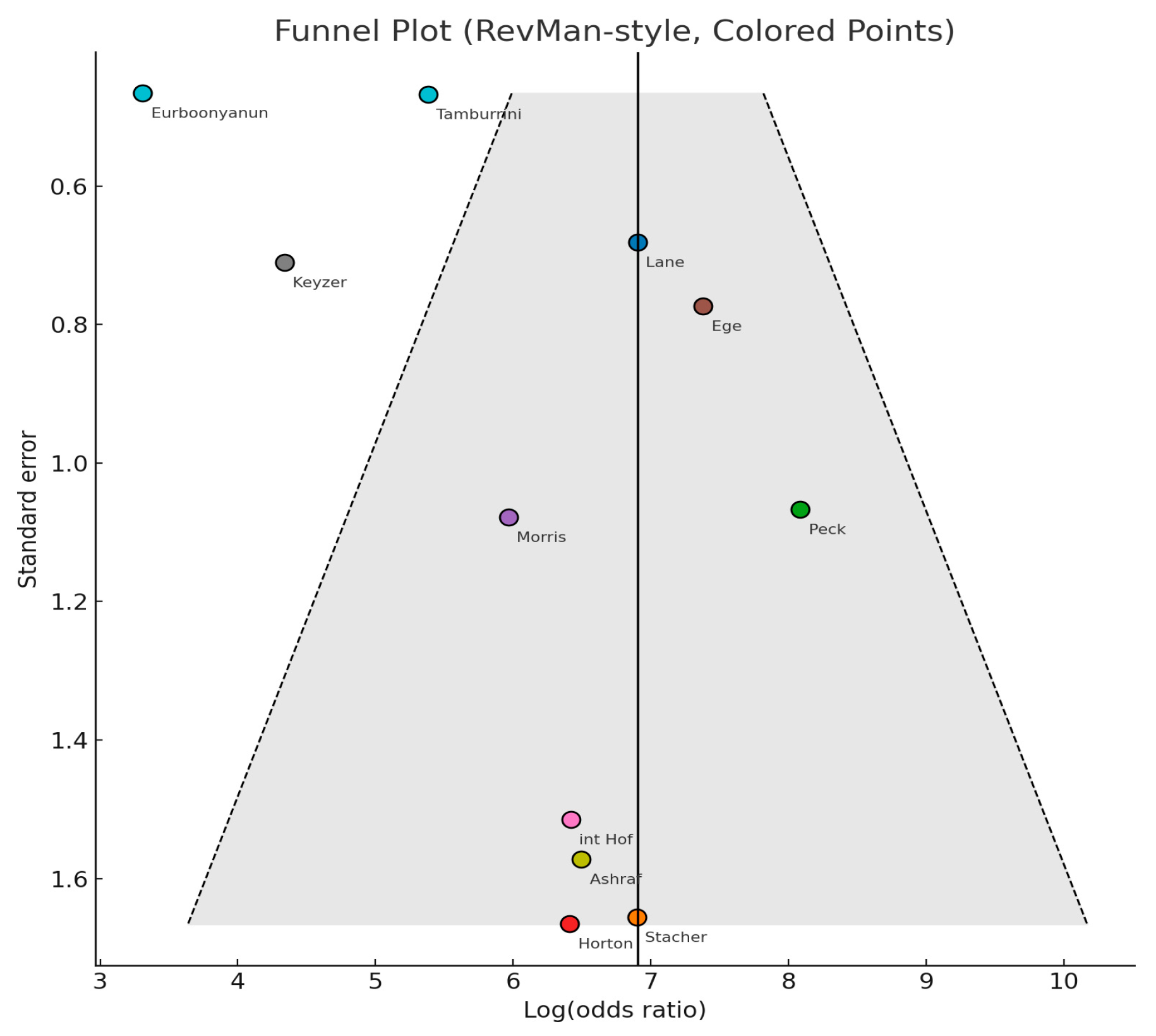

3.3.6. Publication Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| NCCT | Non-Contrast Computed Tomography |

| US | Ultrasound |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PubMed | US National Library of Medicine’s database of biomedical literature |

| Ovid MEDLINE | Online database of biomedical articles |

| EMBASE | Online database of biomedical articles |

| Cochrane Library | Collection of databases of systematic reviews and other evidence |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-Second Edition |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| SROC | Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| HSROC | Hierarchical Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- Addiss, D.G.; Shaffer, N.; Fowler, B.S.; Tauxe, R.V. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 132, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, Y.S.; Choi, J.S. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in South Korea: National registry data. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, M.J.; Guthrie, M.; Cagle, S. Acute Appendicitis: Efficient Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2018, 98, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rud, B.; Vejborg, T.S.; Rappeport, E.D.; Reitsma, J.B.; Wille-Jørgensen, P. Computed tomography for diagnosis of acute appendicitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD009977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Randen, A.; Bipat, S.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Ubbink, D.T.; Stoker, J.; Boermeester, M.A. Acute appendicitis: Meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of CT and graded compression US related to prevalence of disease. Radiology 2008, 249, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammalkorpi, H.E.; Leppäniemi, A.; Lantto, E.; Mentula, P. Performance of imaging studies in patients with suspected appendicitis after stratification with adult appendicitis score. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2017, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury: A review of definition, pathogenesis, risk factors, prevention and treatment. BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.S.; Perazella, M.A.; Yee, J.; Dillman, J.R.; Fine, D.; McDonald, R.J.; Rodby, R.A.; Wang, C.L.; Weinreb, J.C. Use of Intravenous Iodinated Contrast Media in Patients with Kidney Disease: Consensus Statements from the American College of Radiology and the National Kidney Foundation. Radiology 2020, 294, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radetic, M.; DeVita, R.; Haaga, J. When is contrast needed for abdominal and pelvic CT? Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2020, 87, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Lu, S. Abdominal Ultrasound and Its Diagnostic Accuracy in Diagnosing Acute Appendicitis: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 707160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.U.; Oh, S.K. Accuracy of ultrasound for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the emergency department: A systematic review. Medicine 2023, 102, e33397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.J.; Liu, D.M.; Huynh, M.D.; Jeffrey, R.B., Jr.; Mindelzun, R.E.; Katz, D.S. Suspected acute appendicitis: Nonenhanced helical CT in 300 consecutive patients. Radiology 1999, 213, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacher, R.; Portugaller, H.; Preidler, K.W.; Ruppert-Kohlmayr, A.J.; Anegg, U.; Rabl, H.; Spuller, E.; Szolar, D.H. [Acute appendicitis in non-contrast spiral CT: A diagnostic luxury or benefit?]. Rofo Fortschritte Auf Dem Geb. Der Rontgenstrahlen Und Der Nukl. 1999, 171, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.D.; Counter, S.F.; Florence, M.G.; Hart, M.J. A prospective trial of computed tomography and ultrasonography for diagnosing appendicitis in the atypical patient. Am. J. Surg. 2000, 179, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J.; Peck, A.; Peck, C.; Peck, J. The clinical role of noncontrast helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Am. J. Surg. 2000, 180, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ege, G.; Akman, H.; Sahin, A.; Bugra, D.; Kuzucu, K. Diagnostic value of unenhanced helical CT in adult patients with suspected acute appendicitis. Br. J. Radiol. 2002, 75, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, K.T.; Kavanagh, M.; Hansen, P.; Whiteford, M.H.; Deveney, K.; Standage, B. The rational use of computed tomography scans in the diagnosis of appendicitis. Am. J. Surg. 2002, 183, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- In’t Hof, K.H.; van Lankeren, W.; Krestin, G.P.; Bonjer, H.J.; Lange, J.F.; Becking, W.B.; Kazemier, G. Surgical validation of unenhanced helical computed tomography in acute appendicitis. Br. J. Surg. 2004, 91, 1641–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyzer, C.; Zalcman, M.; De Maertelaer, V.; Coppens, E.; Bali, M.A.; Gevenois, P.A.; Van Gansbeke, D. Comparison of US and unenhanced multi-detector row CT in patients suspected of having acute appendicitis. Radiology 2005, 236, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, K.; Ashraf, O.; Bari, V.; Rafique, M.Z.; Usman, M.U.; Chisti, I. Role of focused appendiceal computed tomography in clinically equivocal acute appendicitis. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2006, 56, 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Tamburrini, S.; Brunetti, A.; Brown, M.; Sirlin, C.; Casola, G. Acute appendicitis: Diagnostic value of nonenhanced CT with selective use of contrast in routine clinical settings. Eur. Radiol. 2007, 17, 2055–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurboonyanun, K.; Rungwiriyawanich, P.; Chamadol, N.; Promsorn, J.; Eurboonyanun, C.; Srimunta, P. Accuracy of Nonenhanced CT vs Contrast-Enhanced CT for Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis in Adults. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2021, 50, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R.E.; Stark, J. Diagnostic value of the appendicitis inflammatory response (AIR) score. A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2025, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohle, R.; O’Reilly, F.; O’Brien, K.K.; Fahey, T.; Dimitrov, B.D. The Alvarado score for predicting acute appendicitis: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, M.S.; Hasan, S.; Al-Yahri, O.; Mansor, S.; Al-Tarakji, M.; Obaid, M.; Shah, A.A.; Shehata, M.S.; Singh, R.; Al-Zoubi, R.M.; et al. Adult appendicitis score versus Alvarado score: A comparative study in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Surg. Open Sci. 2023, 14, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhangu, A. Evaluation of appendicitis risk prediction models in adults with suspected appendicitis. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorelić, Z.; Mihanović, J.; Ninčević, S.; Lukšić, B.; Elezović Baloević, S.; Polašek, O. Validity of Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score in Distinguishing Perforated from Non-Perforated Appendicitis in Children. Children 2021, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammalkorpi, H.E.; Mentula, P.; Leppäniemi, A. A new adult appendicitis score improves diagnostic accuracy of acute appendicitis--a prospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Torres, L.C.; Vega-Peña, N.V. Diagnostic utility of the Alvarado scale in older adults with suspected acute appendicitis. Cirugía Y Cir. 2024, 92, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podda, M.; Pisanu, A.; Sartelli, M.; Coccolini, F.; Damaskos, D.; Augustin, G.; Khan, M.; Pata, F.; De Simone, B.; Ansaloni, L.; et al. Diagnosis of acute appendicitis based on clinical scores: Is it a myth or reality? Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021231. [Google Scholar]

- Long, B.; Gottlieb, M. Emergency medicine updates: Acute appendicitis in the adult patient. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2025, 98, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumaoglu, M.O.; Ayan, D.; Vural, A.; Dolanbay, T.; Ozbey, C.; Kulu, A.R. Delta neutrophil index, CRP/albumin ratio, procalcitonin, immature granulocytes, and HALP score in acute appendicitis: Best performing biomarker? Open Med. (Wars) 2025, 20, 20251308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.W.; Juan, L.I.; Wu, M.H.; Shen, C.J.; Wu, J.Y.; Lee, C.C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein and white blood cell count for suspected acute appendicitis. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 100, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Liu, H.; Ni, H.; Qin, X.; Zhu, L. Diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin for overall and complicated acute appendicitis in children: A meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tshuga, N.; Ntola, V.C.; Naidoo, R. The accuracy of white cell count and C-reactive protein in diagnosing acute appendicitis at a tertiary hospital. S. Afr. J. Surg. 2024, 62, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huckins, D.S.; Copeland, K. Diagnostic accuracy of combined WBC, ANC and CRP in adult emergency department patients suspected of acute appendicitis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 44, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Pogorelić, Z.; Agrawal, A.; Muñoz, C.M.L.; Kainth, D.; Verma, A.; Jindal, B.; Agarwala, S.; Anand, S. Utility of Ischemia-Modified Albumin as a Biomarker for Acute Appendicitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorelić, Z.; Jukić, M.; Žuvela, T.; Milunović, K.P.; Maleš, I.; Lovrinčević, I.; Kraljević, J. Salivary Biomarkers in Pediatric Acute Appendicitis: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Children 2025, 12, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.L.; Fan, J.D.; Ho, M.F.; Choo, C.S.C.; Ong, L.Y.; Chen, Y. Salivary biomarker for acute appendicitis in children: A pilot study. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2020, 36, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo Montero, J.; Pérez Riveros, B.P.; Bueso Asfura, O.E.; Rico Jiménez, M.; López-Andrés, N.; Martín-Calvo, N. Leucine-Rich Alpha-2-Glycoprotein as a non-invasive biomarker for pediatric acute appendicitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 3033–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.; Rutjes, A.W.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Kleijnen, J. The development of QUADAS: A tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res Methodol. 2003, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsma, J.B.; Glas, A.S.; Rutjes, A.W.; Scholten, R.J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Zwinderman, A.H. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, R.A.; Tamma, P.D.; Abrahamian, F.M.; Bessesen, M.; Chow, A.W.; Dellinger, E.P.; Edwards, M.S.; Goldstein, E.; Hayden, M.K.; Humphries, R.; et al. 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America on Complicated Intra-abdominal Infections: Diagnostic Imaging of Suspected Acute Appendicitis in Adults, Children, and Pregnant People. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 79 (Suppl. S3), S94–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruzza, E.; Milanese, S.; Li, L.S.K.; Dizon, J. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography and ultrasound for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiography 2022, 28, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaish, H.; Ream, J.; Huang, C.; Troost, J.; Gaur, S.; Chung, R.; Kim, S.; Patel, H.; Newhouse, J.H.; Khalatbari, S.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Unenhanced Computed Tomography for Evaluation of Acute Abdominal Pain in the Emergency Department. JAMA Surg. 2023, 158, e231112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Cong, R.; Wang, M.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, J.; He, Y.; He, B. Comparison of Contrast-enhanced <em>versus</em> Non-enhanced Helical Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis: A Meta-analysis. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2023, 33, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.H.; Tee, Y.S.; Fu, C.Y.; Liao, C.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Hsu, Y.P.; Yeh, C.N.; Wu, E.H. The Role of Noncontrast CT in the Evaluation of Surgical Abdomen Patients. Am. Surg. 2018, 84, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, M.; Kotani, T.; Miyamoto, Y.; Kuriu, Y.; Tsurudome, H.; Nishi, H.; Yabe, M.; Otsuji, E. Noncontrast and contrast enhanced computed tomography for diagnosing acute appendicitis: A retrospective study for the usefulness. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2009, 3, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckett, K.R.; Moriarity, A.K.; Langer, J.M. Safe Use of Contrast Media: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Radiographics 2015, 35, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atema, J.J.; Gans, S.L.; Van Randen, A.; Laméris, W.; van Es, H.W.; van Heesewijk, J.P.; van Ramshorst, B.; Bouma, W.H.; Ten Hove, W.; van Keulen, E.M.; et al. Comparison of Imaging Strategies with Conditional versus Immediate Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography in Patients with Clinical Suspicion of Acute Appendicitis. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 2445–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schräder, R. Contrast material-induced renal failure: An overview. J. Interv. Cardiol. 2005, 18, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlibczuk, V.; Dattaro, J.A.; Jin, Z.; Falzon, L.; Brown, M.D. Diagnostic accuracy of noncontrast computed tomography for appendicitis in adults: A systematic review. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2010, 55, 51–59.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, E.; Salamone, I.; Naso, S.; Bottari, A.; Gaeta, M.; Blandino, A. Can contrast media increase organ doses in CT examinations? A clinical study. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013, 200, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahbaee, P.; Abadi, E.; Segars, W.P.; Marin, D.; Nelson, R.C.; Samei, E. The Effect of Contrast Material on Radiation Dose at CT: Part II. A Systematic Evaluation across 58 Patient Models. Radiology 2017, 283, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.C.; Wong, Y.C.; Wu, C.H.; Chen, H.W.; Wang, L.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Wu, P.W.; Irama, W.; Chen, W.Y.; Chang, C.J. Diagnostic Performance on Low Dose Computed Tomography For Acute Appendicitis Among Attending and Resident Radiologists. Iran. J. Radiol. 2016, 13, e33222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Jeon, B.G.; Hong, C.K.; Kwon, K.W.; Han, S.B.; Paik, S.; Kang, G.H. Low-dose CT for the diagnosis of appendicitis in adolescents and young adults (LOCAT): A pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsser, D.; Maurer, M.; Do, P.L.; Weiß, J.; Notohamiprodjo, M.; Bamberg, F.; Othman, A.E. Reduced scan range abdominopelvic CT in patients with suspected acute appendicitis-impact on diagnostic accuracy and effective radiation dose. BMC Med. Imaging 2019, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.A.; Johnson, J.O.; Kassin, M.T.; Applegate, K.E. The impact of introducing a no oral contrast abdominopelvic CT examination (NOCAPE) pathway on radiology turn around times, emergency department length of stay, and patient safety. Emerg. Radiol. 2014, 21, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, C.; Fraioli, F.; Laghi, A.; Napoli, A.; Pediconi, F.; Danti, M.; Nardis, P.; Passariello, R. High-resolution multidetector CT in the preoperative evaluation of patients with renal cell carcinoma. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003, 180, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCollough, C.H.; Rajiah, P.S. Milestones in CT: Past, Present, and Future. Radiology 2023, 309, e230803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Author | Country | Sample Size | Age (Mean or Range, Y) | Study Design | TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Lane | USA | 300 | 35 (4–89) | Prospective | 110 | 4 | 5 | 181 | 96.0 | 99.0 | 96.5 | 97.3 | 97.0 |

| 1999 | Stacher | Austria | 56 | 36 (18–82) | Prospective | 21 | 0 | 1 | 34 | 95.5 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 97.1 | 98.2 |

| 2000 | Peck | USA | 364 | 25 (2–92) | Retrospective | 103 | 1 | 8 | 252 | 92.8 | 99.6 | 99.0 | 96.9 | 97.5 |

| 2000 | Horton | USA | 49 | 18–65 | Retro + Prospective | 36 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 97.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 92.3 | 98.0 |

| 2002 | Morris | USA | 129 | Mean 35 (16–95) | Retrospective | 38 | 8 | 1 | 82 | 97.4 | 91.1 | 82.6 | 98.8 | 93.0 |

| 2002 | Ege | Turkey | 296 | 24.7 (16–69) | Retrospective | 104 | 3 | 4 | 185 | 96.3 | 98.4 | 97.2 | 97.9 | 97.6 |

| 2004 | in’t Hof | Netherlands | 103 | Median 36 (16–82) | Prospective | 83 | 0 | 4 | 16 | 95.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 96.1 |

| 2005 | Keyzer | Belgium | 94 | Mean 38 (16–81) | Prospective | 26 | 5 | 4 | 59 | 86.7 | 92.2 | 83.9 | 93.7 | 90.4 |

| 2006 | Ashraf | Pakistan | 61 | N/A | Prospective | 21 | 0 | 2 | 38 | 91.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 95.0 | 96.7 |

| 2007 | Tamburrini | Italy | 404 | 38 (18–86) | Retrospective | 73 | 13 | 8 | 310 | 90.1 | 96.0 | 84.8 | 97.4 | 94.8 |

| 2021 | Eurboonyanun | Thailand | 140 | 52 ± 18 (Mean ± SD) | Retrospective | 46 | 11 | 11 | 72 | 80.7 | 86.7 | 80.7 | 86.7 | 84.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, S.K. Diagnostic Accuracy of Non-Contrast CT for Acute Appendicitis in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122163

Oh SK. Diagnostic Accuracy of Non-Contrast CT for Acute Appendicitis in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122163

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Se Kwang. 2025. "Diagnostic Accuracy of Non-Contrast CT for Acute Appendicitis in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122163

APA StyleOh, S. K. (2025). Diagnostic Accuracy of Non-Contrast CT for Acute Appendicitis in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina, 61(12), 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122163