Systematic Review of PET/CT Utilization in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

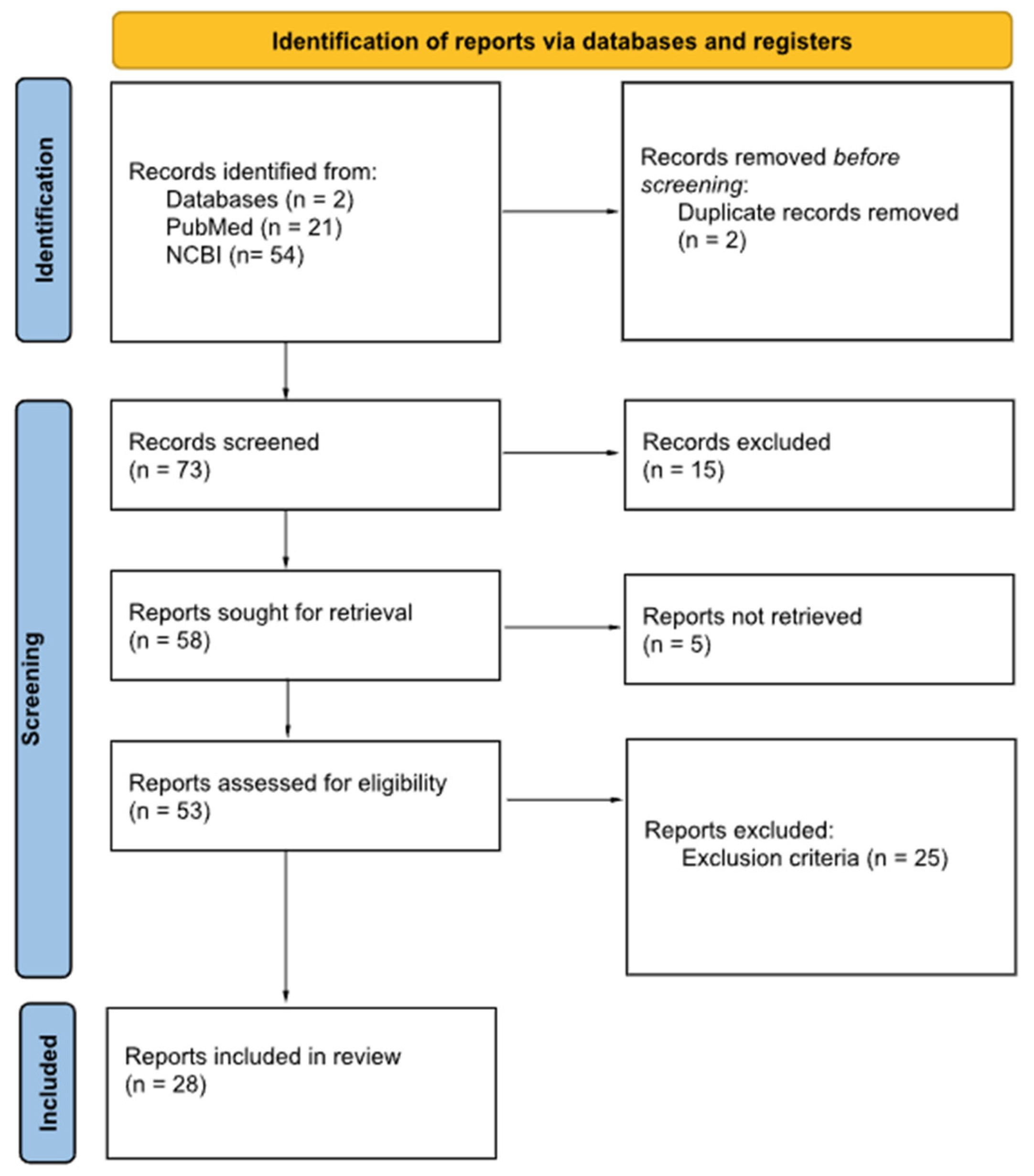

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIA-ALCL | Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma |

| PET/CT | positron emission tomography/computed tomography |

| 18F-FDG | Fluorine-18 Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| BIA-DLBCL | breast implant-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| BIA-SCC | breast implant-associated squamous cell carcinoma |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| NHL | non-Hodgkin lymphomas |

| PTCL | Peripheral T-cell lymphomas |

| NK | natural killer cell |

| ALK | the anaplastic lymphoma kinase |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PTCL-NOS | peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| CHOP | cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone |

References

- Plastic Surgery Statistics. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Available online: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/plastic-surgery-statistics (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Pelc, Z.; Skórzewska, M.; Kurylcio, A.; Olko, P.; Dryka, J.; Machowiec, P.; Maksymowicz, M.; Rawicz-Pruszyński, K.; Polkowski, W. Current Challenges in Breast Implantation. Medicina 2021, 57, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Park, J.-U.; Chang, H. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Current Knowledge on Breast Implant Associated-Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2022, 49, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, G.C.; Keane, A.M.; Diederich, R.; Kennard, K.; Duncavage, E.J.; Myckatyn, T.M. The evaluation of the delayed swollen breast in patients with a history of breast implants. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1174173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Jurgensen-Rauch, A.; Pace, E.; Attygalle, A.D.; Sharma, R.; Bommier, C.; Wotherspoon, A.C.; Sharma, S.; Iyengar, S.; El-Sharkawi, D. Breast Implant-associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: Review and Multiparametric Imaging Paradigms. Radiographics 2020, 40, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health C for D and R. Medical Device Reports of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. FDA 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/breast-implants/medical-device-reports-breast-implant-associated-anaplastic-large-cell-lymphoma (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Tsuyama, N.; Sakamoto, K.; Sakata, S.; Dobashi, A.; Takeuchi, K. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma: Pathology, genetics, and clinical aspects. J. Clin. Exp. Hematop. 2017, 57, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): T-Cell Lymphomas [Internet]. Version 2.2025. Plymouth Meeting (PA): National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/t-cell.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Bewtra, C.; Gharde, P. Current Understanding of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Cureus 2022, 14, e30516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turton, P.; El-Sharkawi, D.; Lyburn, I.; Sharma, B.; Mahalingam, P.; Turner, S.D.; MacNeill, F.; Johnson, L.; Hamilton, S.; Burton, C.; et al. UK Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma on behalf of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery Expert Advisory Group. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 192, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galván, J.R.; Cordera, F.; Arrangoiz, R.; Paredes, L.; Pierzo, J.E. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma presenting as a breast mass: A case report and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 108, 108482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Materazzo, M.; Vanni, G.; Rho, M.; Buonomo, C.; Morra, E.; Mori, S. Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) in a young transgender woman: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 98, 107520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, G.G.; Alban, A.; D’Alì, L.; Mariuzzi, L.; Galvano, F.; Parodi, P.C. Locally advanced breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: A combined medical-surgical approach. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 3483–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro-Garcia, A.; Lacalle-Gonzalez, C.; Santonja, C.; Rodríguez-Pinilla, S.-M.; Cornejo, J.-I.; Morillo, D. Post-Chemotherapy Rebound Thymic Hyperplasia Mimicking Relapse in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: A Case Report. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2021, 44, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, F.; Vigliar, E.; Romeo, V.; Campanino, M.R.; Accurso, A.; Canta, L.; Basso, L.; Cavaliere, C.; Nicolai, E. Breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL): A challenging cytological diagnosis with hybrid PET/MRI staging and follow-up. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandika, V.; Covington, M.F. FDG PET/CT and Ultrasound Evaluation of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2020, 45, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siminiak, N.; Czepczyński, R. PET-CT for the staging of breast implant—Associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Nucl. Med. Rev. Cent. East. Eur. 2019, 22, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montes Fernández, M.; Ciudad Fernández, M.J.; de la Puente Yagüe, M.; Brenes Sánchez, J.; Benito Arjonilla, E.; Moreno Domínguez, L.; Menéndez, B.L.; Rodríguez, J.R.; de la Muela, M.H.; Martinez, B.C.; et al. Breast implant-associated Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL): Imaging findings. Breast J. 2019, 25, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, E.; Singh, K.; Mills, C.; Shapira, I.; Bakst, R.L.; Chadha, M. Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Hematol. 2018, 2018, 2414278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, M.; Zarubova, L.; Klener, P.; Barta, J.; Benkova, K.; Brandejsova, A.; Trneny, M.; Gürlich, R. Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma Associated with Breast Implants: A Case Report of a Transgender Female. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2018, 42, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, M.; van der Sluis, W.B.; de Boer, J.P.; Overbeek, L.I.H.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Rakhorst, H.A.; van der Hulst, R.R.W.J.; Hijmering, N.J.; Bouman, M.-B.; de Jong, D. Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma in a Transgender Woman. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2017, 37, NP83–NP87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shoham, G.; Haran, O.; Singolda, R.; Madah, E.; Magen, A.; Golan, O.; Menes, T.; Arad, E.; Barnea, Y. Our Experience in Diagnosing and Treating Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta-Shah, N.; Clemens, M.W.; Horwitz, S.M. How I treat breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood 2018, 132, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, P.; Giza, A.; Kolenda, M.; Fendler, W.; Braun, M.; Chudobiński, C.; Chałubińska-Fendler, J.; Araszkiewicz, M.; Loga, K.; Lembas, L.; et al. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) in Poland: Analysis of patient series and practical guidelines for breast surgeons. Arch. Med. Sci. 2023, 19, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacko, A.; Lloyd, T. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: A pictorial review. Insights Imaging 2018, 9, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.; Sindhu, K.; Bakst, R.L. A Rare Case of a Transgender Female with Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Treated with Radiotherapy and a Review of the Literature. J. Investig. Med. High. Impact Case Rep. 2019, 7, 2324709619842192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crèvecoeur, J.; Jossa, V.; Somja, J.; Parmentier, J.-C.; Nizet, J.-L.; Crèvecoeur, A. Description of Two Cases of Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Associated with a Breast Implant. Case Rep. Radiol. 2019, 2019, 6137198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekwudo, D.E.; Ifabiyi, T.; Gbadamosi, B.; Haberichter, K.; Yu, Z.; Amin, M.; Shaheen, K.; Stender, M.; Jaiyesimi, I. Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Oncol. Med. 2017, 2017, 6478467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, R.; Maruccia, M.; De Pascale, A.; Di Napoli, A.; Ingravallo, G.; Giudice, G. The management of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in the setting of pregnancy: Seeking for clinical practice guidelines. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2021, 48, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglic, D.; Moss, W.; Pires, G.; Agarwal, A.; Matsen, C.; Kwok, A. A Case Report of Misdiagnosed Breast Implant-associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma with Lymphatic Extension. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vets, J.; Marcelis, L.; Schepers, C.; Dorreman, Y.; Verbeek, S.; Vanwalleghem, L.; Gieraerts, K.; Meylaerts, L.; Lesaffer, J.; Devos, H.; et al. Breast implant associated EBV-positive Diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma: An underrecognized entity? Diagn. Pathol. 2023, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corines, M.J.; Krystel-Whittemore, M.; Murray, M.; Mango, V. Uncommon Tumors and Uncommon Presentations of Cancer in the Breast. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2021, 13, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, E.; Kamenko, S.; Snir, O.L.; Hansen, J. Silicone granuloma mimicking Breast Implant Associated Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL): A case report. Case Rep. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2020, 7, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paule, C.F.P.; Pedroso, R.B.; de Barros Carvalho, M.D.; Pelloso, F.C.; Roma, A.M.; da Silva Freitas, R.; Cavalcante, J.M.; Ribeiro, H.F.; Pelloso, S.M. Anaplastic lymphoma associated with breast implants—Early diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e7727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, L.; Herlihy, W.; Holmes, H.; Pin, P. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2017, 30, 441–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, K.; Alrifai, T.; Grant-Szymanski, K.; Kouris, G.J.; Venugopal, P.; Mahon, B.; Karmali, R. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma and the role of brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) therapy: A case report and review of the literature. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kim, B.; Predmore, Z.S.; Mattke, S.; van Busum, K.; Gidengil, C.A. Breast Implant-associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: Updated Results from a Structured Expert Consultation Process. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2015, 3, e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orofino, N.; Guidotti, F.; Cattaneo, D.; Sciumè, M.; Gianelli, U.; Cortelezzi, A.; Iurlo, A. Marked eosinophilia as initial presentation of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2016, 57, 2712–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachy, E.; Broccoli, A.; Dearden, C.; de Leval, L.; Gaulard, P.; Koch, R.; Morschhauser, F.; Trümper, L.; Zinzani, P.L. Controversies in the Treatment of Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma. Hemasphere 2020, 4, e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Lv, W.; Zhao, C.; Xiong, M.; Hou, K.; Wu, M.; Ren, Y.; Zeng, N.; et al. Current Progress in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 785887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blombery, P.; Thompson, E.R.; Jones, K.; Arnau, G.M.; Lade, S.; Markham, J.F.; Li, J.; Deva, A.; Johnstone, R.W.; Khot, A.; et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals activating JAK1 and STAT3 mutations in breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2016, 101, e387–e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, R.A.; Holland, M.; Sieber, D.A.; Wen, K.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Kadin, M.E.; Bean, G.R. Synchronous Breast Implant-associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma and Invasive Carcinoma: Genomic Profiling and Management Implications. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrada, B.E.; Miranda, R.N.; Rauch, G.M.; Arribas, E.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Clemens, M.W.; Fanale, M.; Haideri, N.; Mustafa, E.; Larrinaga, J.; et al. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: Sensitivity, specificity, and findings of imaging studies in 44 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 147, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Geus-Oei, L.-F.; Vriens, D.; Arens, A.I.J.; Hutchings, M.; Oyen, W.J.G. FDG-PET/CT based response-adapted treatment. Cancer Imaging 2012, 12, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Parihar, A.S.; Dehdashti, F.; Wahl, R.L. FDG PET/CT-based Response Assessment in Malignancies. Radiographics 2023, 43, e220122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description of Lymphoma Cells | Stage | |

|---|---|---|

| T—Tumor Extent (penetration of capsule) | ||

| T1 | Only in the effusion or on the luminal side of the capsule | 1A → T1N0M0 |

| T2 | Superficial infiltration of the luminal side of the capsule | 1B → T2N0M0 |

| T3 | Cell aggregates or sheets penetrate the capsule | 1C → T3N0M0 |

| T4 | Cells infiltrate beyond the capsule | 2A → T4N0M0 |

| N—Nodal Involvement | ||

| N0 | No lymph node involvement | |

| N1 | One local or regional lymph node involved | 2B → T1–3N1M0 |

| N2 | More than one local or regional lymph node involved | 3 → T4N1–2M0 |

| M—Metastatic Disease | ||

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |

| M1 | Distant metastasis present | 4 → T1–4N0–2M1 |

| Additional Insights | Follow-Up | Disease Extension | Staging | Number of Patients | Age and Gender | Author, Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | Yes | Hypermetabolic lesions in the right breast and right axilla, mild uptake in the bone marrow | Yes | 1 | 44 F | Galván, 2023 [11] |

| The patient was a male-to-female transgender | No | No focal periprosthetic, locoregional, or distant pathological uptake (cT1N0M0) | Yes | 1 | 27 F | Materazzo, 2022 [12] |

| Died due to cardiovascular complications | Yes | Locally advanced disease, involving the 5th, 6th and 7th left ribs (pT4N0M0) | Yes | 1 | Not mentioned F | Caputo, 2021 [13] |

| Adverse effect to chemotherapy which led to uptake in the thymus due to rebound hyperplasia | Yes | Uptake in the breast nodules, enlarged axillary lymph nodes and a mediastinal lesion | Yes | 1 | 40 F | Lazaro-Garcia, 2021 [14] |

| After the PET/CT scan, a PET/MRI scan was performed | No | Small volume effusion surrounding the left breast implant with mild tracer uptake | Yes | 1 | 55 F | Verde, 2020 [15] |

| 3 out of 4 patients did PET/CT scans to assess disease extension, and the remaining patient did a PET/CT scan postoperatively | Yes | P1: Faint capsular uptake on axial fused PET/CT and maximal intensity projection images | Yes | 4 | 58 F, 56 F, 67 F, 66 F | Pandika, 2020 [16] |

| P2: 3 foci of peri-implant uptake and an FDG-avid supraclavicular lymph node, bilateral peri-implant fluid with focal uptake within the left one | ||||||

| P3: FDG-avid lymphadenopathy and soft tissues masses in the left breast, axilla, subpectoral and supraclavicular regions; | ||||||

| N/A | No | P1: Peri-implant uptake with increased uptake in the left axillary lymph node | Yes | 2 | 60 F | Siminiak, 2019 [17] |

| P2: Uptake at the lower pole of the left implant and infiltration of lymph nodes in left axillary | ||||||

| N/A | No | Diffuse uptake in the peri-implant capsule with no metastatic disease | Yes | 1 | 36 F | Montes Fernández, 2019 [18] |

| N/A | Yes | Multiple lesions in the right breast, two hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the right axilla, a hypermetabolic band posterior to the implant involving the pectoralis minor muscle | Yes | 1 | 58 F | Berlin, 2018 [19] |

| The patient was a male-to-female transgender | Yes | IE stage on Ann Arbor classification | Yes | 1 | 33 F | Patzelt, 2018 [20] |

| T4N0M0 | ||||||

| The patient was a male-to-female transgender | No | IE stage on Ann Arbor classification | Yes | 1 | 56 F | de Boer, 2017 [21] |

| 2 out of 4 patients did a PET/CT scan for staging, the other 2 having done a PET/CT scan after the operation | Yes | P1: Peri-implant uptake, with no axillary or distant uptake | Yes | 4 | 64 F, 57 F, 48 F, 74 F | Shoham, 2024 [22] |

| P2: Weak absorption of a lymph node in the left axilla | ||||||

| N/A | Yes | P1: No evidence of lymphadenopathy or suspicion for lymphoma outside of the left breast | Yes | 2 | 59 F | Mehta-Shah, 2018 [23] |

| P2: Hypermetabolic 2-cm mass on the capsule of the left breast implant, 2.5 to 3-cm hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the left axilla | ||||||

| Out of 7 patients, 3 of them did not do a PET/CT scan | Yes | P1: Uptake in the breast and axillary nodes | Yes | 7 | 44 F, 50 F, 30 F, 59 F, 34 F, 46 F, 64 F | Pluta, 2020 [24] |

| The authors report that in 2 patients that did preoperative scans, PET/CT overestimated the staging | P2: Not done | |||||

| One patient had a false positive result in the post-operative PET/CT scan | P3: Negative | |||||

| P4: Not done | ||||||

| P5: Uptake in the breast and axillary nodes | ||||||

| P6: Uptake in the breast | ||||||

| P7: Not done | ||||||

| One patient did only a postoperative PET/CT scan; | Yes | P1: Large mixed-density mass with intense FDG activity, deep within and invading the right breast and pectoralis muscles; metastatic disease spread to the lung and bone | Yes | 3 | 48 F, 64 F, 33 F | Chacko, 2018 [25] |

| P2: Flattened rim of soft tissue, located inferomedially in the left breast, with ill-defined margins and moderate FDG uptake | ||||||

| P3: not done | ||||||

| The patient was a male-to-female transgender | Yes | 4 abnormal hypermetabolic soft tissue densities surrounding the right breast implant | Yes | 1 | 58 F | Ali, 2019 [26] |

| N/A | Yes | N/A | No | 2 | 58 F, 47 F | Crèvecoeur, 2019 [27] |

| N/A | N/A | Increased uptake along the anterior chest wall, slightly greater on the right than the left | Yes | 1 | 65 F, | Ezekwudo, 2017 [28] |

| The patient was a pregnant woman; | Yes | Uptake in the left breast with no capsular mass, nor lymphatic or visceral involvement | Yes | 1 | 40 F | Elia, 2021 [29] |

| The patient was not evaluated according with the NCCN guideline and BIA-ALCL was initially misdiagnosed | N/A | >3 hypermetabolic lymph nodes along the course of the distal right external iliac vessels | Yes | 1 | 70 F | Maglic, 2021 [30] |

| N/A | Yes | P1: large tumoral mass at the upper-external quadrant of the right breast, in close contact with the implant with a layer of fluid surrounding the implant | Yes | 2 | 75 F, 45 F | Vets, 2023 [31] |

| P2: hypermetabolic lesion in the left breast with moderate uptake in the axillary lymph nodes | ||||||

| N/A | N/A | Left breast hypermetabolic mass and hypermetabolic but non-enlarged left axillary lymph nodes | Yes | 1 | 85 F | Corines, 2021 [32] |

| N/A | N/A | Mild radiotracer uptake along the right chest wall mass, moderately intense uptake along the left lower outer breast quadrant and at the mediastinal and hilar nodes, and intense uptake in the left axillary nodes; | Yes | 1 | 75 F | Shepard, 2020 [33] |

| N/A | N/A | P1: was done postoperative and did not reveal suspicious metabolic activity | Yes | 2 | 42 F, 30 F | de Paule, 2023 [34] |

| P2: no areas of increased metabolic activity | ||||||

| N/A | N/A | The PET/CT scan was done postoperative and was negative for metastatic disease | Yes | 1 | 60 F | Keith, 2017 [35] |

| N/A | Yes | Small hypermetabolic soft tissue focus anterior to the right breast implant and additional focus of hyperactivity in the colon | Yes | 1 | 55 F | Richardson, 2017 [36] |

| N/A | N/A | Hypermetabolic activity in the anterior outer quadrant of the breast | Yes | 1 | 59 F | Kim, 2015 [37] |

| The patient was a male-to-female transgender | Yes | Uptake in the left breast | Yes | 1 | 78 F | Orofino, 2016 [38] |

| The case presented itself initially with mild leukocytosis with hypereosinophilia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mititelu, M.R.; Mititelu, T.S.; Crăciun, D.; Solomon, Ș.B.; Tutui, C.; Rugină, A.I.; Marinescu, S.A. Systematic Review of PET/CT Utilization in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Medicina 2025, 61, 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122160

Mititelu MR, Mititelu TS, Crăciun D, Solomon ȘB, Tutui C, Rugină AI, Marinescu SA. Systematic Review of PET/CT Utilization in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122160

Chicago/Turabian StyleMititelu, Mihaela Raluca, Teodora Sidonia Mititelu, Dumitru Crăciun, Ștefan Bogdan Solomon, Ciprian Tutui, Andrei Iulian Rugină, and Silviu Adrian Marinescu. 2025. "Systematic Review of PET/CT Utilization in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122160

APA StyleMititelu, M. R., Mititelu, T. S., Crăciun, D., Solomon, Ș. B., Tutui, C., Rugină, A. I., & Marinescu, S. A. (2025). Systematic Review of PET/CT Utilization in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Medicina, 61(12), 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122160