Cutaneous Melanoma in the Context of Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

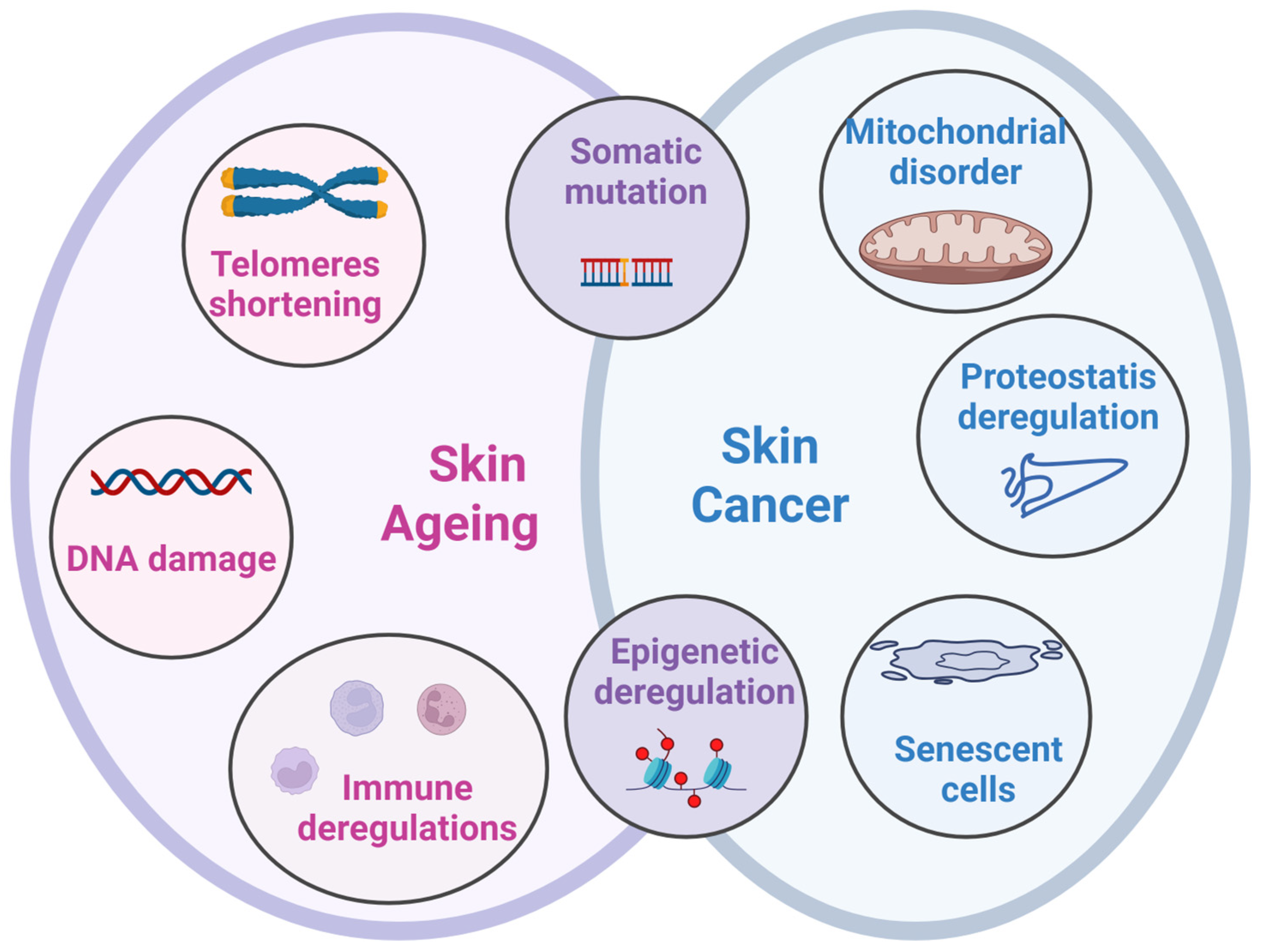

2. Populational Ageing and Skin Cancers

3. Skin Melanoma in Aged Population

3.1. Genetic and Epigenetic Traits in Aged Melanoma Patients

3.2. Cellular Senescence and Immunosenescence in Melanoma

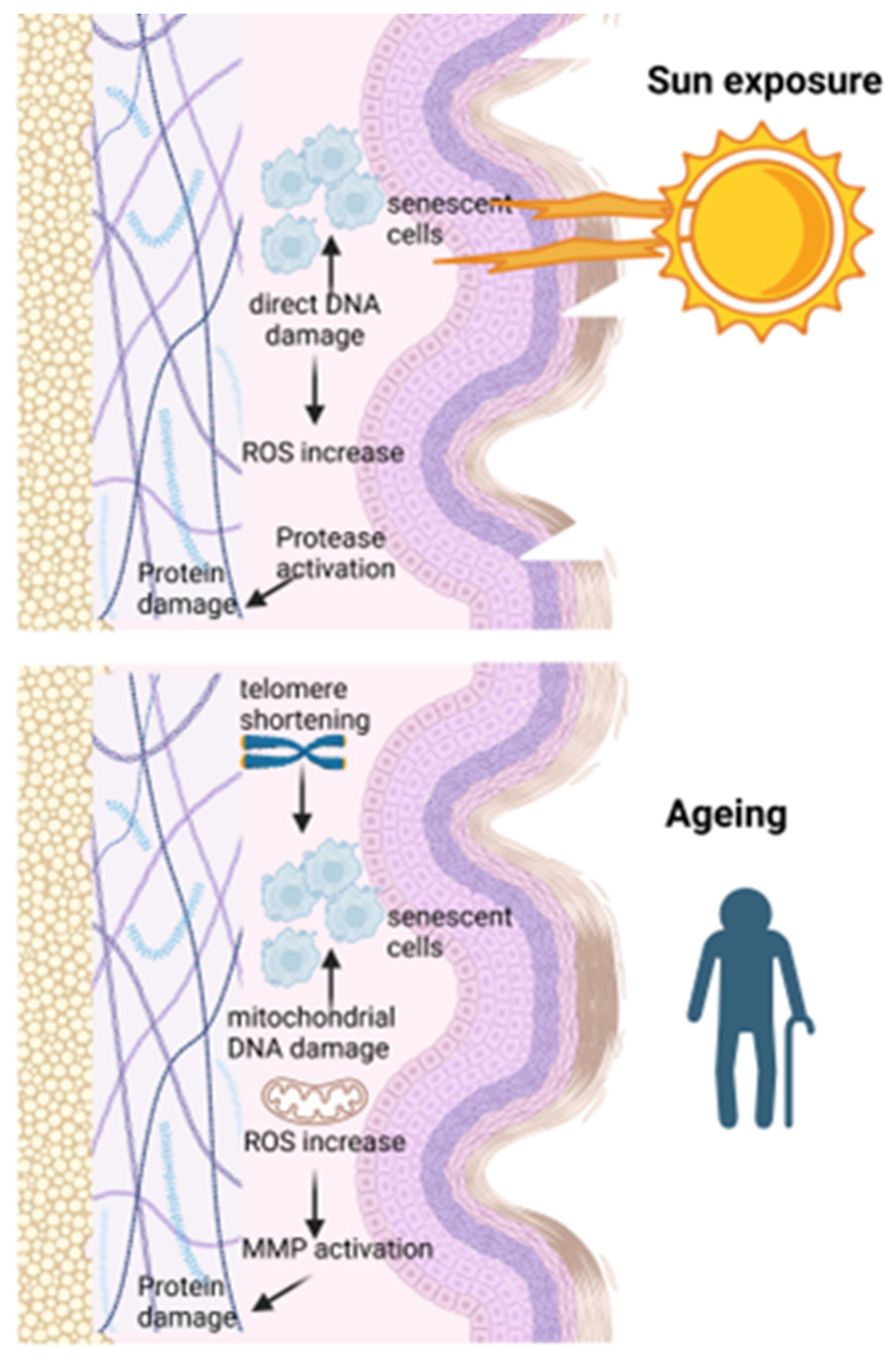

3.3. Ageing at the Sub-Cellular Level

3.4. Other Factors Enhancing Ageing Processes

4. Ageing Modulators Influencing Skin Cancer Initiation

5. Melanoma Therapy in Aged Patients

5.1. Immunotherapy in Aged Patients

5.2. Predictors of Immunotherapy Efficacy in Older Patients

6. Integrative Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aCGH | array Comparative Genomic Hybridization |

| ABCC2 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 2 |

| AK | actinic keratosis |

| AMPK | 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ANGPTL2 | angiopoietin-349 like protein 2 |

| APC | antigen presenting cells |

| ASC | adipose stromal/stem cells |

| AXL | tyrosine kinase receptors |

| BCC | basal cell carcinoma |

| BMP2 | bone morphogenetic protein 2 |

| BRAF | B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase |

| CA14 | Carbonic Anhydrase 14 |

| CAF | cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CDKN | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor |

| CpG | cytosine–guanine base |

| CNV | copy number variation |

| CRGs | circadian rhythm genes |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C Chemokine Receptor Type 4 |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DNAm | DNA methylation |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| EGR3 | Early Growth Response 3 |

| EV | extracellular vesicles |

| EZH2 | enhancer of zeste homolog 2 |

| FBXW7 | F-box and WD repeat domain containing 7 |

| FMS | Familial Melanoma Syndrome |

| GRP78 | 78-kilodalton glucose-regulated protein |

| H2AX | H2A histone family member X |

| H3K4me1/ H3K9me3 | Histone H3 methylation |

| HAPLN1 | Hyaluronan And Proteoglycan Link Protein 1 |

| HDAC | histone deacetylases |

| HRLs | hypoxia-related lncRNAs |

| hTERT | telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| ISI | immunosenescence index |

| IRE1 | Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 |

| KC | keratinocyte cancers |

| LDHB | Lactate Dehydrogenase B |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| LEP | leptin |

| lncRNA | long noncoding RNA |

| Mfn | mitofusin |

| MMP | metalloproteinase |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NMSC | non-melanoma cancers |

| NRAS | Neuroblastoma RAS Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| OS | overall survival |

| p16INK4a | inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PN | proteostasis network |

| P-P53 | tumor antigen p53 |

| PSEN2 | presenilin 2 |

| pTNM | pathological tumor-node-metastasis staging |

| RB1 | RB Transcriptional Corepressor 1 |

| RFS | recurrence-free survival |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| S1pr1 | sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 |

| SASP | senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SCC | squamous cell carcinoma |

| SETD2 | SET Domain-Containing Protein 2 |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| SM | skin melanomas |

| SMAD | Suppressor of Mothers Against Decapentaplegic |

| snoRNAs | Small nucleolar RNAs |

| SQ | squalene |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TERT | telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| TGFβ | transforming growth factor |

| TKIs | tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| TIL | tumor infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| TMB | tumor mutational burden |

| TNFα | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| UV | ultraviolet radiation |

References

- Jain, N.; Li, J.L.; Tong, L.; Jasmine, F.; Kibriya, M.G.; Demanelis, K.; Oliva, M.; Chen, L.S.; Pierce, B.L. DNA methylation correlates of chronological age in diverse human tissue types. Epigenet. Chromatin. 2024, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, M.R.; Youn, S.; Kim, D.H.; Pack, S.P. Natural compounds for preventing age-related diseases and cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkan, A.; de Glas, N.A.; Portielje, J.E.A. Immunotherapy: Should we worry about immunosenescence? Ageing Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 1, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riew, T.R.; Kim, Y.S. Mutational landscapes of normal skin and their potential implications in the development of skin cancer: A comprehensive narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, V.; Pawelec, G. Ageing and cancer research & treatment. Ageing Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 1, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochez, L.; Volkmer, B.; Hoorens, I.; Garbe, C.; Röcken, M.; Schüz, J.; Whiteman, D.C.; Autier, P.; Greinert, R.; Boonen, B. Skin cancer in Europe today and challenges for tomorrow. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, R.; Demuru, E.; Baili, P.; Troussard, X.; Katalinic, A.; Lopez, M.D.C.; Innos, K.; Santaquilani, M.; Blum, M.; Ventura, L.; et al. Complete cancer prevalence in Europe in 2020 by disease duration and country (EUROCARE-6): A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezono, Y.; Sato, Y.; Noto, M.; Yamada, K.; Noguchi, N.; Hasunuma, N.; Osada, S.; Manabe, M. Incidence rate of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is rapidly increasing in Akita Prefecture: Urgent alert for super-aged society. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buja, A.; Rugge, M.; Trevisiol, C.; Zanovello, A.; Brazzale, A.R.; Zorzi, M.; Vecchiato, A.; Del Fiore, P.; Tropea, S.; Rastrelli, M.; et al. Cutaneous melanoma in older patients. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunssen, A.; Jansen, L.; Eisemann, N.; Waldmann, A.; Weberpals, J.; Kraywinkel, K.; Eberle, A.; Holleczek, B.; Zeissig, S.R.; Brenner, H.; et al. A population-based registry study on relative survival from melanoma in Germany stratified by tumor thickness for each histologic subtype. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdain, H.; Lavaud, J.; Descours, C.; Auditeau, E.; Bernard, P. Management of melanoma in elderly patients over 80 Years. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2024, 104, adv41029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottner, J.; Fastner, A.; Lintzeri, D.A.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Griffiths, C.E.M. Skin health of community-living older people: A scoping review. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Keim, U.; Eigentler, T.K.; Amaral, T.; Katalinic, A.; Holleczek, B.; Martus, P.; Leiter, U. Time trends in incidence and mortality of cutaneous melanoma in Germany. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1272–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, N.; Seviiri, M.; Ong, J.-S.; Gordon, S.; Neale, R.E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Olsen, C.M.; MacGregor, S.; Law, M.H. Genetic analysis of perceived youthfulness reveals differences in how men’s and women’s age is assessed. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 2230–2239.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz-Stablein, B.; Llewellyn, S.; Bearzi, P.; Grochulska, K.; Rutjes, C.; Aitken, J.; Janda, M.; O’rOuke, P.; Soyer, H.; Green, A. High variability in anatomic patterns of cutaneous photodamage: A population-based study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrantonaki, E.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Nieczaj, R.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Eckardt, R. Prevalence of skin diseases in hospitalized geriatric patients: Association with gender, duration of hospitalization and geriatric assessment. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 50, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzori, L.; Ferreli, C.; Rongioletti, F. Diagnostic challenges in the mature patient: Growing old gracefully. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 36, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, M.; Zhang, X.; Leng, L.; Zheng, H.; Li, J. Analysing the causal relationship between potentially protective and risk factors and cutaneous melanoma: A Mendelian randomization study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreres, J.R.; Caturla, J.M.; Sánchez, J.S.; Gamissans, M.; Vinyals, A.; Bermejo, J.; Penín, R.; Fabra, À.; Marcoval, J. Changes in the location of cutaneous melanoma over the past 30 years a retrospective observational study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2024, 115, T852–T857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.; Dalle, S.; Dereure, O.; Mortier, L.; Dalac-Rat, S.; Dutriaux, C.; Leccia, M.-T.; Legoupil, D.; Montaudié, H.; Maubec, E.; et al. Differential gradients of immunotherapy vs targeted therapy efficacy according to the sun-exposure pattern of the site of occurrence of primary melanoma: A multicenter prospective cohort study (MelBase). Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1250026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarrón, A.; Lorrio, S.; González, S.; Juarranz, Á. Fernblock prevents dermal cell damage induced by Visible and Infrared A radiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, P.; Sayegh, S.; Laphanuwat, P.; Devine, O.P.; Fantecelle, C.H.; Sikora, J.; Chambers, E.S.; Karagiannis, S.N.; Gomes, D.C.O.; Kulkarni, A.; et al. Multiple outcomes of the germline p16(INK4a) mutation affecting senescence and immunity in human skin. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüser, L.; Chhabra, Y.; Gololobova, O.; Wang, V.; Liu, G.; Dixit, A.; Rocha, M.R.; Harper, E.I.; Fane, M.E.; Marino-Bravante, G.E.; et al. Aged fibroblast-derived extracellular vesicles promote angiogenesis in melanoma. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fane, M.; Weeraratna, A.T. How the ageing microenvironment influences tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantinou, S.M.; Bennett, D.C. Cell senescence and the genetics of melanoma development. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2024, 63, e23273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.; Stockfleth, E. Light and Skin. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2021, 55, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.; Horioka-Duplix, M.; Chen, Y.; Saca, V.R.; Ceraudo, E.; Chen, Y.; Sakmar, T.P. The role of signaling pathways mediated by the GPCRs CysLTR1/2 in melanocyte proliferation and senescence. Sci. Signal. 2024, 17, eadp3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, I.; Murali, R.; Müller, H.; Wiesner, T.; Jackett, L.A.; Scholz, S.L.; Cosgarea, I.; van de Nes, J.A.; Sucker, A.; Hillen, U.; et al. Activating cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 (CYSLTR2) mutations in blue nevi. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, X.-J. TGFβ signaling in photoaging and uv-induced skin cancer. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Diaz Olea, X.; Zhuang, A.; Zheng, B.; Kim, H.; Ronai, Z.A. Epigenetic mechanisms in melanoma development and progression. Trends Cancer 2025, 11, 736–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.F.; Tejedor, J.R.; Bayón, G.F.; Fernández, A.F.; Fraga, M.F. Distinct chromatin signatures of DNA hypomethylation in aging and cancer. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskaran, S.P.; Ravichandran, J.; Shree, P.; Thengumthottathil, V.; Karthikeyan, B.S.; Samal, A. UVREK: Development and analysis of an expression profile knowledgebase of biomolecules induced by ultraviolet radiation exposure. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 927–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzi´nska, M.; Parodi, A.; Balakireva, A.V.; Chepikova, O.E.; Venanzi, F.M.; Zamyatnin Jr, A. A cellular aging characteristics and their association with age-related disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liendl, L.; Grillari, J.; Schosserer, M. Raman fingerprints as promising markers of cellular senescence and aging. Geroscience 2020, 42, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’arino, A.; Caputo, S.; Eibenschutz, L.; Piemonte, P.; Buccini, P.; Frascione, P.; Bellei, B. Skin cancer microenvironment: What we can learn from skin aging? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øvrebø, J.I.; Ma, Y.; Edgar, B.A. Cell growth and the cell cycle: New insights about persistent questions. BioEssays 2022, 44, 2200150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.T.; Ganier, C.; Allison, D.B.; Tchkonia, T.; Khosla, S.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lynch, M.D.; Wyles, S.P. Mapping epidermal and dermal cellular senescence in human skin aging. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Carroll, B. Senescence in the ageing skin: A new focus on mTORC1 and the lysosome. FEBS J. 2025, 292, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.C. Review: Are moles senescent? Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2024, 37, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, E.-G.; Nichita, L.; Popp, C.; Zurac, S.; Neagu, M. Assessment of RAS-RAF-MAPK pathway mutation status in healthy skin, benign nevi, and cutaneous melanomas: Pilot study using droplet digital PCR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeremian, R.; Lytvyn, Y.; Fotovati, R.; Georgakopoulos, J.R.; Gooderham, M.; Yeung, J.; Sachdeva, M.; Lefrançois, P.; Litvinov, I.V. Distinct signatures of mitotic age acceleration in cutaneous melanoma and acquired melanocytic nevi. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 1897–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.M.; Weinberger, B.; Didierlaurent, A.; Lambert, P.-H. Age-related changes in the immune system and challenges for the development of age-specific vaccines. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2477300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snodgrass, R.G.; Jiang, X.; Stephensen, C.B.; Laugero, K.D. Cumulative physiological stress is associated with age-related changes to peripheral T lymphocyte subsets in healthy humans. Immun. Ageing 2023, 20, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, A.N.; Surcel, M.; Isvoranu, G.; Constantin, C.; Neagu, M. Healthy ageing reflected in innate and adaptive immune parameters. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2022, 17, 1513–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, R.; Jiang, L.; Wang, T.; Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Gao, Y.; Jia, R.; Fan, X.; Su, W. Aging-induced immune microenvironment remodeling fosters melanoma in male mice via γδ17-Neutrophil-CD8 axis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicaksono, D.; Taslim, N.A.; Lau, V.; Syahputra, R.A.; Alatas, A.I.; Putra, P.P.; Tallei, T.E.; Tjandrawinata, R.R.; Tsopmo, A.; Kim, B.; et al. Elucidation of anti-human melanoma and anti-aging mechanisms of compounds from green seaweed Caulerpa racemosa. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, L.; Qi, J.; Ye, Z.; Nie, G.; Leng, S. Machine learning-derived immunosenescence index for predicting outcome and drug sensitivity in patients with skin cutaneous melanoma. Genes Immun. 2024, 25, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Rodriguez, J.; Naigeon, M.; Goldschmidt, V.; Dugage, M.R.; Seknazi, L.; Danlos, F.X.; Champiat, S.; Marabelle, A.; Michot, J.-M.; Massard, C.; et al. Immunosenescence, inflammaging, and cancer immunotherapy efficacy. Expert. Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2022, 22, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pang, Y.; Fan, X. Mitochondria in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging: From mechanisms to therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overwijk, W.W.; Restifo, N.P. B16 as a mouse model for human melanoma. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001, 39, 20.1.1–20.1.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, M.; Constantin, C.; Popescu, I.D.; Zipeto, D.; Tzanakakis, G.; Nikitovic, D.; Fenga, C.; Stratakis, C.A.; Spandidos, D.A.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Inflammation and metabolism in cancer cell—Mitochondria key player. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Hou, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z. Healthy mitochondria inhibit the metastatic melanoma in lungs. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 2707–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guan, T.; Shafiq, K.; Yu, Q.; Jiao, X.; Na, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, G.; Kong, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 88, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskorz, W.M.; Krętowski, R.; Cechowska-Pasko, M. Marizomib promotes senescence or long-term apoptosis in melanoma cancer cells. Molecules 2024, 29, 5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarallo, D.; Martínez, J.; Leyva, A.; Mónaco, A.; Perroni, C.; Tassano, M.; Gambini, J.P.; Cappetta, M.; Durán, R.; Moreno, M.; et al. Mitofusin 1 silencing decreases the senescent associated secretory phenotype, promotes immune cell recruitment and delays melanoma tumor growth after chemotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zeng, C.; Bin, J.; Tang, H.; Li, W. Identifying novel circadian rhythm biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis of melanoma by an integrated bioinformatics and machine learning approach. Aging 2024, 16, 11824–11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino-Bravante, G.E.; Carey, A.E.; Hüser, L.; Dixit, A.; Wang, V.; Kaur, A.; Liu, Y.; Ding, S.; Schnellmann, R.; Gerecht, S.; et al. Age-dependent loss of HAPLN1 erodes vascular integrity via indirect upregulation of endothelial ICAM1 in melanoma. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, M.; Dobre, E.G. New insights into the link between melanoma and obesity. In Obesity and Lipotoxicity; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Engin, A.B., Engin, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1460, pp. 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, M.; Constantin, C.; Surcel, M. Systemic circulating leptin—Aiding new dimension of immune-related skin carcinogenesis and lipid metabolism. South East Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, P.; Indini, A.; De Luca, M.; Merelli, B.; Mariuk-Jarema, A.; Teterycz, P.; Rogala, P.; Lugowska, I.; Cybulska-Stopa, B.; Labianca, A.; et al. Body mass index (BMI) and outcome of metastatic melanoma patients receiving targeted therapy and immunotherapy: A multicenter international retrospective study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietri, C.; Tomaipitinca, L.; Scatozza, F.; Facchiano, A. Expression of genes related to lipid handling and the obesity paradox in melanoma: Database analysis. JMIR Cancer 2020, 6, e16974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheau, C.; Draghici, C.; Ilie, M.A.; Lupu, M.; Solomon, I.; Tampa, M.; Georgescu, S.R.; Caruntu, A.; Constantin, C.; Neagu, M.; et al. Neuroendocrine factors in melanoma pathogenesis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruntu, C.; Boda, D.; Constantin, C.; Caruntu, A.; Neagu, M. Catecholamines increase in vitro proliferation of murine b16f10 melanoma. Acta Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dravillas, C.E.; Coleman, S.S.; Hoyd, R.; Caryotakis, G.; Denko, L.; Chan, C.H.; Churchman, M.L.; Denko, N.; Dodd, R.D.; Eljilany, I.; et al. The tumor microbiome as a predictor of outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 1978–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L.D.; Young, A.R.J.; Young, C.N.J.; Soilleux, E.J.; Fielder, E.; Weigand, B.M.; Lagnado, A.; Brais, R.; Ktistakis, N.T.; Wiggins, K.A.; et al. Temporal inhibition of autophagy reveals segmental reversal of ageing with increased cancer risk. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Kasraian, Z.; Rezvani, H.R. Energy metabolism in skin cancers: A therapeutic perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2017, 1858, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catic, A. Cellular metabolism and aging. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2018, 155, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Xu, T.; Yu, S.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J. Mitochondrial metabolism and cancer therapeutic innovation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, S.A. Telomeres and human disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2025, 17, a041684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliou, S.; Fragkiadaki, P.; Vakonaki, E.; Ioannou, P.; Renieri, E.; Manolis Tzatzarakis, M.; Tsatsakis, A. Telomere length as a marker of biological age. In Telomeres, 1st ed.; Imprint Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2025; p. 41. ISBN 9781003568094. [Google Scholar]

- Shou, S.; Maolan, A.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, X.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Geer, E.; Pu, Z.; Hua, B.; et al. Telomeres, telomerase, and cancer: Mechanisms, biomarkers, and therapeutics. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreikos, D.A.; Spandidos, D.A. Telomere length and skin cancer risk: A systematic review and metaanalysis of melanoma, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2025, 30, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, C. Telomeres in skin aging. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, M.S.; Hollestein, L.M.; Bastiaannet, E.; Posthuma, E.F.; van Akkooi, A.J.; Kukutsch, N.A.; Aarts, M.J.; Wakkee, M.; Lemmens, V.E.; Louwman, M.W. Melanoma in older patients: Declining gap in survival between younger and older patients with melanoma. Acta Oncol. 2020, 59, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Herck, Y.; Feyaerts, A.; Alibhai, S.; Papamichael, D.; Decoster, L.; Lambrechts, Y.; Pinchuk, M.; Bechter, O.; Herrera-Caceres, J.; Bibeau, F.; et al. Is cancer biology different in older patients? Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e663–e677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druskovich, C.; Kelley, J.; Aubrey, J.; Palladino, L.; Wright, G.P. A review of melanoma subtypes: Genetic and treatment considerations. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 131, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, A.N.; Sinnamon, A.J.; Roses, R.E.; Kelz, R.R.; Elder, D.E.; Xu, X.; Pockaj, B.A.; Zager, J.S.; Fraker, D.L.; Karakousis, G.C. Relationship between age and likelihood of lymph node metastases in patients with intermediate thickness melanoma (1.01–4.00 mm): A National Cancer Database study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, A.; Kapiteijn, E.; van den Bos, F.; Aarts, M.J.B.; van den Berkmortel, F.W.P.J.; Blank, C.U.; Bloem, M.; Blokx, W.A.M.; Boers-Sonderen, M.J.; Bonenkamp, J.J.; et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy in older patients with stage III and resected stage IV melanoma: Toxicity and recurrence-free survival outcomes from the Dutch melanoma treatment registry. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 212, 115056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, S.; Podlipnik, S.; Boada, A.; Martí, R.M.; Sabat, M.; Yélamos, O.; Zarzoso-Muñoz, I.; Azón-Masoliver, A.; López-Castillo, D.; Solà, J.; et al. Network of Melanoma Centres of Catalonia. Melanoma-specific survival is worse in the elderly: A multicentric cohort study. Melanoma Res. 2023, 33, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kooij, M.K.; Wetzels, M.J.; Aarts, M.J.; Berkmortel, F.W.v.D.; Blank, C.U.; Boers-Sonderen, M.J.; Dierselhuis, M.P.; de Groot, J.W.B.; Hospers, G.A.; Piersma, D.; et al. Age does matter in adolescents and young adults versus older adults with advanced melanoma; a national cohort study comparing tumor characteristics, treatment pattern, toxicity and response. Cancers 2020, 12, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatsirisupachai, K.; Lagger, C.; de Magalhães, J.P. Age-associated differences in the cancer molecular landscape. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thau, H.; Gerjol, B.P.; Hahn, K.; von Gudenberg, R.W.; Knoedler, L.; Stallcup, K.; Emmert, M.Y.; Buhl, T.; Wyles, S.P.; Tchkonia, T.; et al. Senescence as a molecular target in skin aging and disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 105, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadnejad, H.; Emamat, H.; Zand, H. The effect of resveratrol on cellular senescence in normal and cancer cells: Focusing on cancer and age-related diseases. Nutr. Cancer. 2019, 71, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Chung, S.O.; Kim, J.K.; Park, S.U. Recent studies on resveratrol and its biological and pharmacological activity. EXCLI J. 2017, 16, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Yin, N.; Wele, P.; Li, F.; Dave, S.; Lin, J.; Xiao, H.; Wu, X. Resveratrol in disease prevention and health promotion: A role of the gut microbiome. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 5878–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. Targeting aging pathways with natural compounds: A review of curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate, thymoquinone, and resveratrol. Immun. Ageing 2025, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Yan, G.; Yang, L.; Kong, L.; Guan, Y.; Sun, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Han, Y.; Wang, X. Cancer chemoprevention: Signaling pathways and strategic approaches. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Risks of Picato for Actinic Keratosis Outweigh Benefits. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/risks-picato-actinic-keratosis-outweigh-benefits (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Parrado, C.; Mascaraque, M.; Gilaberte, Y.; Juarranz, A.; Gonzalez, S. Fernblock (Polypodium leucotomos Extract): Molecular Mechanisms and Pleiotropic Effects in Light-Related Skin Conditions, Photoaging and Skin Cancers, a Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luze, H.; Nischwitz, S.P.; Zalaudek, I.; Müllegger, R.; Kamolz, L.P. DNA repair enzymes in sunscreens and their impact on photoageing-A systematic review. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2020, 36, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Majidian, M.; Kolli, H.; Rosenthal, A.; Wilson, A.; Rock, J.; Yao, Z.; Moy, R. Ultraviolet B- rays induced gene alterations and dna repair enzymes in skin tissue. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2023, 22, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, A.E.; Weeraratna, A.T. Entering the TiME machine: How age-related changes in the tumor immune microenvironment impact melanoma progression and therapy response. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 262, 108698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochems, A.; Bastiaannet, E.; Aarts, M.J.; van Akkooi, A.C.; Berkmortel, F.W.v.D.; Boers-Sonderen, M.J.; Eertwegh, A.J.v.D.; de Glas, N.G.; de Groot, J.W.B.; Haanen, J.B.; et al. Outcomes for systemic therapy in older patients with metastatic melanoma: Results from the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Campayo, N.; Paradela de la Morena, S.; Pértega-Díaz, S.; Tejera Vaquerizo, A.; Fonseca, E. Prognostic significance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in elderly with cutaneous melanoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surcel, M.; Constantin, C.; Caruntu, C.; Zurac, S.; Neagu, M. Inflammatory cytokine pattern is sex-dependent in mouse cutaneous melanoma experimental model. J. Immunol. Res. 2017, 2017, 9212134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, Y.; Fane, M.E.; Pramod, S.; Hüser, L.; Zabransky, D.J.; Wang, V.; Dixit, A.; Zhao, R.; Kumah, E.; Brezka, M.L.; et al. Sex-dependent effects in the aged melanoma tumor microenvironment influence invasion and resistance to targeted therapy. Cell 2024, 187, 6016–6034.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sun, Y.; Le, J.; Dian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, F.; Deng, G.; Lei, S.; Su, J. Predictors of survival in immunotherapy-based treatments in advanced melanoma: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S. Characterization the prognosis role and effects of snoRNAs in melanoma patients. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e14944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makalakshmi, M.K.; Banerjee, A.; Pathak, S.; Paul, S.; Sharma, N.R.; Anandan, B. A pilot study on the efficacy of a telomerase activator in regulating the proliferation of A375 skin cancer cell line. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 52, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Zhu, L.; Fu, Y.; Ye, Z.; Deng, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y. Prognostic and therapeutic roles of SETD2 in cutaneous melanoma. Aging 2024, 16, 9692–9708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, J.W.; Mahadevan, L.C.; Clayton, A.L. Dynamic histone H3 methylation during gene induction: HYPB/Setd2 mediates all H3K36 trimethylation. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Q.; Deng, Y.; Wei, R.; Ma, K.; Tang, J.; Deng, Y.P. Tumor-infiltrating macrophage associated lncRNA signature in cutaneous melanoma: Implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and immunotherapy. Aging 2024, 16, 4518–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Ye, Z. Identification of hypoxic-related lncRNAs prognostic model for revealing clinical prognostic and immune infiltration characteristic of cutaneous melanoma. Aging 2024, 16, 3734–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menefee, D.S.; McMasters, A.; Pan, J.; Li, X.; Xiao, D.; Waigel, S.; Zacharias, W.; Rai, S.N.; McMasters, K.M.; Hao, H. Age-related transcriptome changes in melanoma patients with tumor-positive sentinel lymph nodes. Aging 2020, 12, 24914–24939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, Y.; Hubeli, B.; Turko, P.; Barysch, M.; Martínez-Gómez, J.M.; Zamboni, N.; Rogler, G.; Dummer, R.; Levesque, M.P.; Scharl, M. The serum metabolome serves as a diagnostic biomarker and discriminates patients with melanoma from healthy individuals. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.M.; Murphy, J.E.J. Sunlight radiation as a villain and hero: 60 years of illuminating research. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2019, 95, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullenders, L.H.F. Solar UV damage to cellular DNA: From mechanisms to biological effects. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1842–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dermitzakis, I.; Kyriakoudi, S.A.; Chatzianagnosti, S.; Chatzi, D.; Vakirlis, E.; Meditskou, S.; Manthou, M.E.; Theotokis, P. Epigenetics in skin homeostasis and ageing. Epigenomes 2025, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hoi, E.T.; Santegoets, S.J.; Mooijaart, S.P.; Van Heemst, D.; Özkan, A.; Verdegaal, E.M.E.; Slingerland, M.; Kapiteijn, E.; van der Burg, S.H.; Portielje, J.E.A.; et al. Blood based immune biomarkers associated with clinical frailty scale in older patients with melanoma receiving checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Immun. Ageing 2024, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotto, C. Mechanisms of melanoma aggressiveness with age. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampa, M.; Georgescu, S.R.; Mitran, M.I.; Mitran, C.I.; Matei, C.; Caruntu, A.; Scheau, C.; Nicolae, I.; Matei, A.; Caruntu, C.; et al. Current perspectives on the role of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of basal cell carcinoma. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Patients > 65 Years | Patients < 65 Years | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | |||

| Breslow index | Mean 4.9 mm | Mean 1.9 mm | [9,11,74] |

| Ulceration | increased | decreased | [9] |

| Mitotic rate | High | Medium | [9,11,74] |

| TIL | Low | High | [9,75] |

| Preponderant tumor localization | Head and neck | Trunk and extremities | [74] |

| Subtypes frequency | Nodular melanoma and lentigo maligna | Superficial spreading melanoma | [76] |

| Nodal metastasis frequency | Low | High | [77] |

| Melanoma-specific survival | Low | High | [10,78,79] |

| Mutational pattern | |||

| BRAF mutation frequency | Low | High | [11,80] |

| NRAS mutation frequency | High | Low | [11,80] |

| Immune pattern | |||

| Naïve CD8 + T cells | Low levels | Normal levels | [5,22] |

| Tissue-resident effector memory CD8 + T cells | High levels | Normal levels | [42,43] |

| T cell proliferation and APC ability | NS | NS | [5,22] |

| Treg | Low levels | Normal | [42,43] |

| Chemotaxis, cytotoxicity, cytokine production | Reduced | Normal | [42,43] |

| Treatment response rates | NS | NS | [5,22] |

| Other cellular and molecular characteristics | |||

| Cellular senescence | High | Low | [26,33,81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neagu, M.; Constantin, C.; Zurac, S. Cutaneous Melanoma in the Context of Aging. Medicina 2025, 61, 2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122115

Neagu M, Constantin C, Zurac S. Cutaneous Melanoma in the Context of Aging. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122115

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeagu, Monica, Carolina Constantin, and Sabina Zurac. 2025. "Cutaneous Melanoma in the Context of Aging" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122115

APA StyleNeagu, M., Constantin, C., & Zurac, S. (2025). Cutaneous Melanoma in the Context of Aging. Medicina, 61(12), 2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122115