Associations Between Cognitive Performance and Motor Signs in Older Adults with Alzheimer’s Dementia

Abstract

1. Introduction

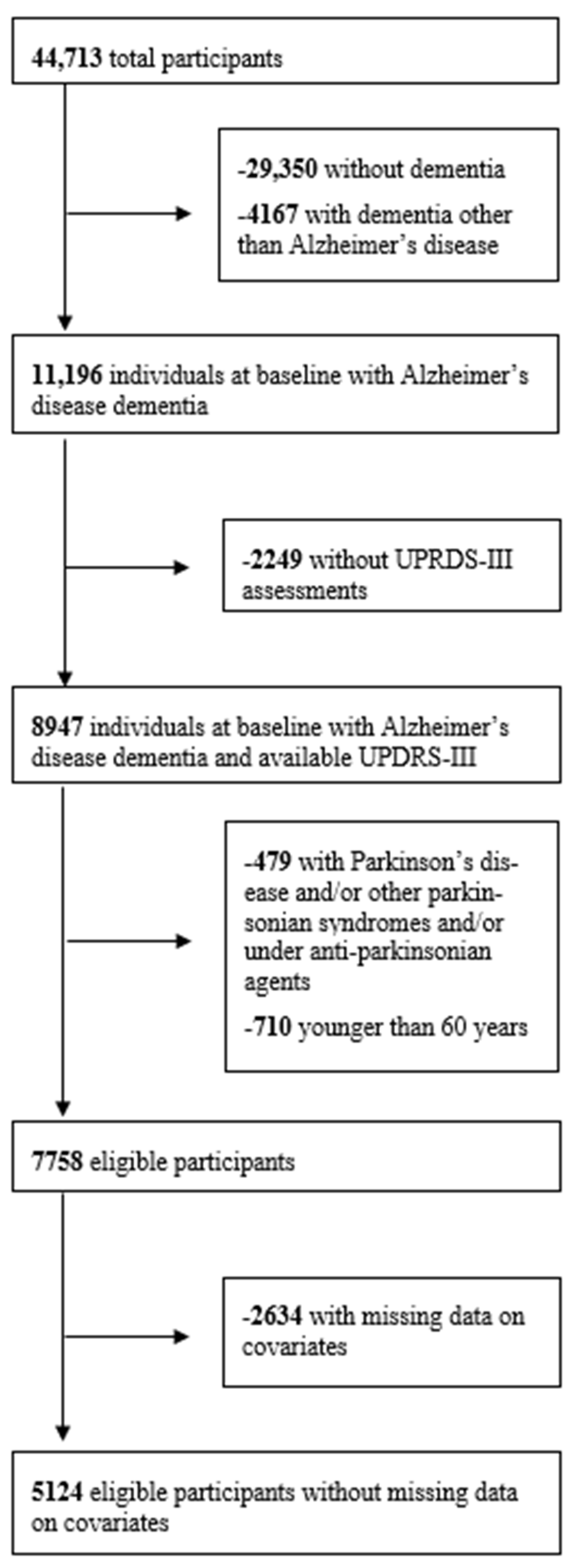

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measurement of Motor Signs

2.2. Measurement of Cognitive Performance

2.3. Covariates Considered

2.4. Statistical Analysis

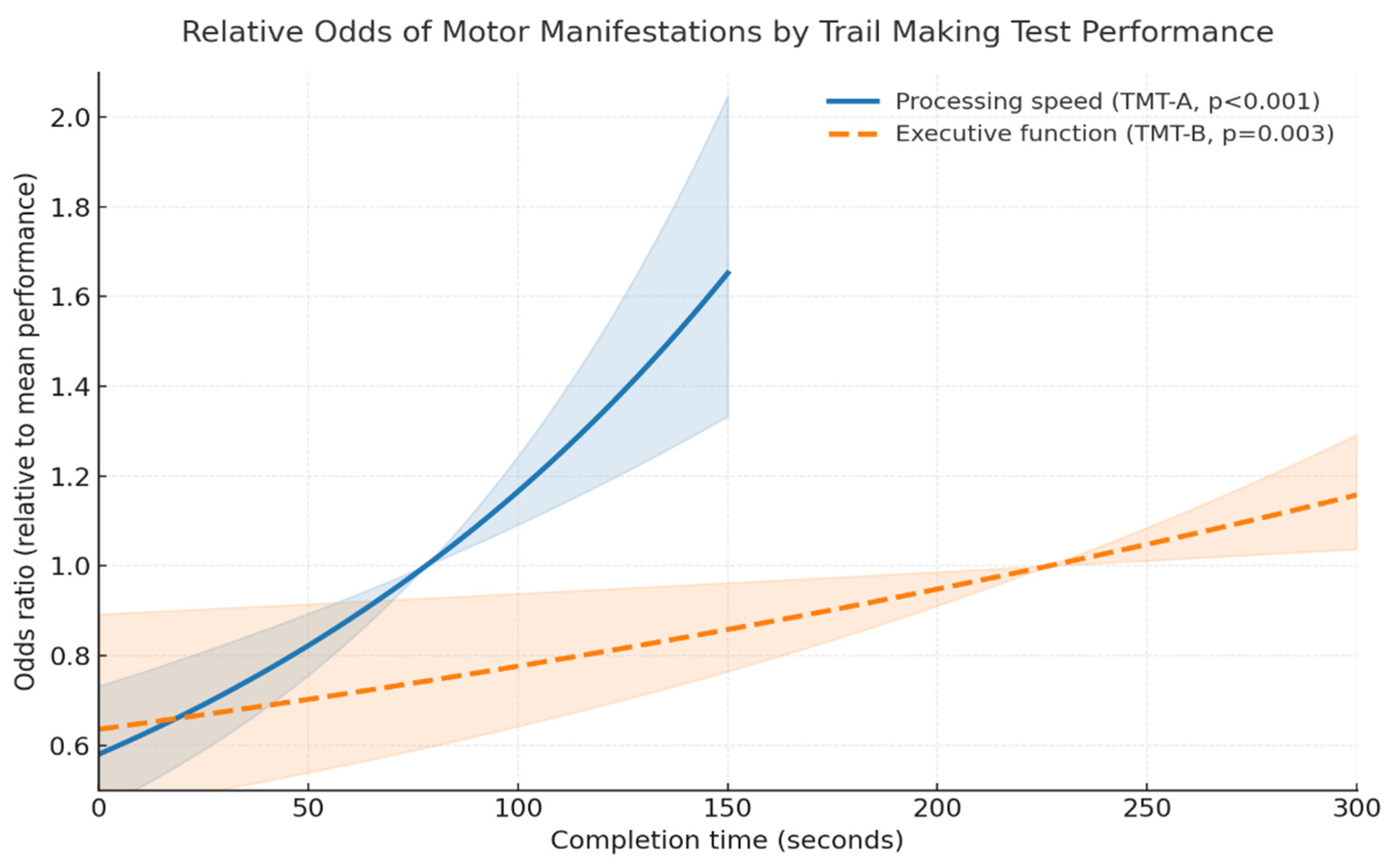

3. Results

Associations Between Cognitive Performance and Motor Signs in Older Adults with AD

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s dementia |

| NACC | National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre |

| UDS | Uniform Data Set |

| NIA/NIH | National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health |

| ADCs | Alzheimer’s Disease Centres |

| UPDRS-III | Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part-III |

| WMS-R | Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised |

| BNT-30 | 30-item version of the Boston Naming Test |

| DST | Digit Span Test |

| TMT-A | Trail Making Test—Part A |

| TMT-B | Trail Making Test—Part B |

| GDS | Geriatric Depression Scale |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| CDR | Clinical Dementia Rating |

| NPS | Neuropsychiatric severity score |

| SSRIs | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| SNRIs | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| MAOIs | Monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| NPI-Q | Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire |

References

- Liampas, I.; Siokas, V.; Ntanasi, E.; Kosmidis, M.H.; Yannakoulia, M.; Sakka, P.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M.; Scarmeas, N.; Dardiotis, E. Cognitive trajectories preluding the imminent onset of Alzheimer’s disease dementia in individuals with normal cognition: Results from the HELIAD cohort. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Lozada, A.R. Trends in Deaths from Falls Among Adults Aged 65 Years or Older in the US, 1999–2020. JAMA 2023, 329, 1605–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Vetrano, D.L.; Kalpouzos, G.; Welmer, A.-K.; Laukka, E.J.; Marseglia, A.; Fratiglioni, L.; Rizzuto, D. Brain Changes and Fast Cognitive and Motor Decline in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2023, 78, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Dove, A.; Arfanakis, K.; Qi, X.; Bennett, D.A.; Xu, W. Association of Motor Function with Cognitive Trajectories and Structural Brain Differences. Neurology 2023, 101, e1718–e1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisman, G.; Moustafa, A.; Shafir, T. Thinking, Walking, Talking: Integratory Motor and Cognitive Brain Function. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.L.; Decety, J. Motor cognition: A new paradigm to study self–other interactions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004, 14, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanalingham, K.K.; Byrne, E.J.; Thornton, A.; Sambrook, M.A.; Bannister, P. Motor and cognitive function in Lewy body dementia: Comparison with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1997, 62, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.A.; Chakravarthy, S.; Phillips, J.R.; Crouse, J.J.; Gupta, A.; Frank, M.J.; Hall, J.M.; Jahanshahi, M. Interrelations between cognitive dysfunction and motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: Behavioral and neural studies. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 27, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.X.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.K.; Peng, F.; Wang, Y.; Yang, K.; Liu, Z.Y.; Liu, F.T.; Wu, J.J.; Wang, J. Associations between cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. 2017, 7, e00719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawamoto, N.; Honda, M.; Hanakawa, T.; Fukuyama, H.; Shibasaki, H. Cognitive Slowing in Parkinson’s Disease: A Behavioral Evaluation Independent of Motor Slowing. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 5198–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hessen, E.; Stav, A.L.; Auning, E.; Selnes, P.; Blomsø, L.; Holmeide, C.E.; Johansen, K.K.; Eliassen, C.F.; Reinvang, I.; Fladby, T.; et al. Neuropsychological Profiles in Mild Cognitive Impairment due to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. J. Park. Dis. 2016, 6, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenkinsop, A.; van der Flier, W.M.; Wolk, D.; Lehmann, M.; Howard, R.; Frost, C.; Barnes, J. Non-memory cognitive symptom development in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlesimo, G.A.; Oscar-Berman, M. Memory deficits in Alzheimer’s patients: A comprehensive review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 1992, 3, 119–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folia, V.; Liampas, I.; Siokas, V.; Silva, S.; Ntanasi, E.; Yannakoulia, M.; Sakka, P.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Scarmeas, N.; Dardiotis, E.; et al. Language performance as a prognostic factor for developing Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and mild cognitive impairment: Results from the population-based HELIAD cohort. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2023, 29, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liampas, I.; Dimitriou, N.; Siokas, V.; Messinis, L.; Nasios, G.; Dardiotis, E. Cognitive trajectories preluding the onset of different dementia entities: A descriptive longitudinal study using the NACC database. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liampas, I.; Demiri, S.; Stamati, P.; Lazarou, L.; Michailides, C.; Marogianni, C.; Tsika, A.; Siokas, V.; Dardiotis, E. Factors associated with motor manifestations in older adults with Alzheimer’s dementia: A cross-sectional analysis. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2025, 16, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmeas, N.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M.; Papadimitriou, A.; Dubois, B.; Sarazin, M.; Brandt, J.; Albert, M.; Marder, K.; Bell, K.; Honig, L.S.; et al. Motor signs during the course of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2004, 63, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, P.L.; Hausdorff, J.M. The Role of Higher-Level Cognitive Function in Gait: Executive Dysfunction Contributes to Fall Risk in Alzheimer’s Disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2007, 24, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.P.; Robbins, T.W. The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoyroo, R.; Hands, B.; Caeyenberghs, K.; de Luca, A.; Leemans, A.; Wigley, A.; Hyde, C. Association between Motor Planning and the Frontoparietal Network in Children: An Exploratory Multimodal Study. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2022, 28, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, G.; Howells, H.; Sciortino, T.; Leonetti, A.; Rossi, M.; Nibali, M.C.; Gay, L.G.; Fornia, L.; Bellacicca, A.; Viganò, L.; et al. Frontal pathways in cognitive control: Direct evidence from intraoperative stimulation and diffusion tractography. Brain 2019, 142, 2451–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liampas, I.; Siokas, V.; Zoupa, E.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Dardiotis, E. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and incident Lewy body dementia in male versus female older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 78, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekly, D.L.; Ramos, E.M.; Lee, W.W.; Deitrich, W.D.; Jacka, M.E.; Wu, J.; Hubbard, J.L.; Koepsell, T.D.; Morris, J.C.; Kukull, W.A. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Database: The Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2007, 21, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.C.; Weintraub, S.; Chui, H.C.; Cummings, J.; DeCarli, C.; Ferris, S.; Foster, N.L.; Galasko, D.; Graff-Radford, N.; Peskind, E.R.; et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): Clinical and Cognitive Variables and Descriptive Data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2006, 20, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, S.; Salmon, D.; Mercaldo, N.; Ferris, S.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Chui, H.; Cummings, J.; DeCarli, C.; Foster, N.L.; Galasko, D.; et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): The Neuropsychologic Test Battery. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2009, 23, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeith, I.G.; Dickson, D.W.; Lowe, J.; Emre, M.; O’Brien, J.T.; Feldman, H.; Cummings, J.; Duda, J.E.; Lippa, C.; Perry, E.K.; et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 2005, 65, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.; Drachman, D.; Folstein, M.; Katzman, R.; Price, D.; Stadlan, E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984, 34, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, D.; Snowden, J.S.; Gustafson, L.; Passant, U.; Stuss, D.; Black, S.; Freedman, M.; Kertesz, A.; Robert, P.H.; Albert, M.; et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998, 51, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, G.C.; Tatemichi, T.K.; Erkinjuntti, T.; Cummings, J.L.; Masdeu, J.C.; Garcia, J.H.; Amaducci, L.; Orgogozo, J.-M.; Brun, A.; Hofman, A.; et al. Vascular dementia: Diagnostic criteria for research studies: Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology 1993, 43, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siokas, V.; Liampas, I.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Dardiotis, E. Association between Motor Signs and Cognitive Performance in Cognitively Unimpaired Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the NACC Database. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.A.; Shannon, K.M.; Beckett, L.A.; Wilson, R.S. Dimensionality of Parkinsonian Signs in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1999, 54, M191–M196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, G.; Louis, E.D.; Cote, L.; Perez, M.; Mejia-Santana, H.; Andrews, H.; Harris, J.; Waters, C.; Ford, B.; Frucht, S.; et al. Contribution of Aging to the Severity of Different Motor Signs in Parkinson Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Harvey, D.J.; DeCarli, C.S.; Zhang, L.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Olichney, J.M. Extrapyramidal Signs by Dementia Severity in Alzheimer Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2013, 27, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmeas, N.; Albert, M.; Brandt, J.; Blacker, D.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Papadimitriou, A.; Dubois, B.; Sarazin, M.; Wegesin, D.; Marder, K.; et al. Motor signs predict poor outcomes in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2005, 64, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liampas, I.; Siokas, V.; Stamati, P.; Zoupa, E.; Tsouris, Z.; Provatas, A.; Kefalopoulou, Z.; Chroni, E.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Dardiotis, E. Motor signs and incident dementia with Lewy bodies in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 73, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, D. WMS-R: Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised; Psychological Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Moms, J.C.; Heyman, A.; Mohs, R.C.; Hughes, J.P.; van Belle, G.; Fillenbaum, G.; Mellits, E.D.; Clark, C. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assesment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1989, 39, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodglass, H.; Kaplan, E.; Weintraub, S. BDAE: The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination. Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hultsch, D.F.; Strauss, E.; Hunter, M.A.; MacDonald, S.W.S.; Craik, F.I.M.; Salthouse, T.A. The Handbook of Aging and Cognition; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liampas, I.; Siokas, V.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Dardiotis, E. The Relationship between Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Cognitive Performance in Older Adults with Normal Cognition. Medicina 2022, 58, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.L.; Mega, M.; Gray, K.; Rosenberg-Thompson, S.; Carusi, D.A.; Gornbein, J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994, 44, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, M.; Guerra, A.; Colella, D.; Cioffi, E.; Paparella, G.; Di Vita, A.; D’ANtonio, F.; Trebbastoni, A.; Berardelli, A. Bradykinesia in Alzheimer’s disease and its neurophysiological substrates. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Komatsu, J.; Nakamura, K.; Sakai, K.; Samuraki-Yokohama, M.; Nakajima, K.; Yoshita, M. Diagnostic Criteria for Dementia with Lewy Bodies: Updates and Future Directions. J. Mov. Disord. 2020, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, D.; Sekiya, H.; Maier, A.R.; Murray, M.E.; Koga, S.; Dickson, D.W. Parkinsonism in Alzheimer’s disease without Lewy bodies in association with nigral neuron loss: A data-driven clinicopathologic study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e14628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Bennett, D.; Gilley, D.; Beckett, L.; Schneider, J.; Evans, D. Progression of parkinsonian signs in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2000, 54, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfared, A.A.T.; Phan, N.T.N.; Pearson, I.; Mauskopf, J.; Cho, M.; Zhang, Q.; Hampel, H. A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease and Strategies for Future Advancements. Neurol. Ther. 2023, 12, 1257–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Guarino, P.D.; Dysken, M.W.; Pallaki, M.; Asthana, S.; Llorente, M.D.; Love, S.; Vertrees, J.E.; Schellenberg, G.D.; Sano, M. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Caregiver Burden in Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease: The TEAM-AD VA Cooperative Study. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2018, 31, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angioni, D.; Cummings, J.; Lansdall, C.J.; Middleton, L.; Sampaio, C.; Gauthier, S.; Cohen, S.; Petersen, R.C.; Rentz, D.M.; Wessels, A.M.; et al. Clinical Meaningfulness in Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Trials. A Report from the EU-US CTAD Task Force. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 11, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade-Guerrero, J.; Martínez-Orozco, H.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; Santiago-Balmaseda, A.; Delgado-Minjares, K.M.; Pérez-Segura, I.; Baéz-Cortés, M.T.; Del Toro-Colin, M.A.; Guerra-Crespo, M.; Arias-Carrión, O.; et al. Alzheimer’s Disease: Understanding Motor Impairments. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | No Motor Sign (N = 3785) | At Least One Motor Sign (N = 1339) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75.4 ± 7.7 | 79.5 ± 7.9 | p < 0.001 |

| Sex (male/%) | 1716/45.3% | 588/43.9% | p = 0.368 |

| Education (years) | 14.3 ± 3.6 | 13.8 ± 3.9 | p < 0.001 |

| Race (Caucasian/African American/Asian/other) | 3198/446/50/91 (84.5/11.8/1.3/2.4%) | 1103/164/29/43 (82.4/12.2/2.2/3.2%) | p = 0.051 |

| APOE genotype (e3e3/e3e4/e3e2/e4e4/e4e2/e2e2) | 1316/1658/148/544/113/6 (34.8/43.7/3.9/14.4/3.0/0.2%) | 552/522/88/135/39/3 (41.2/39.0/6.6/10.1/2.9/0.2%) | p < 0.001 |

| GDS (15) | 2.4 ± 2.5 | 2.8 ± 2.8 | p < 0.001 |

| NPS (none/mild/moderate or severe) | 646/1323/1816 (17.0/35.0/48.0%) | 184/427/728 (13.7/31.9/54.4%) | p = 0.001 |

| Global CDR (0.5/1.0/2.0/3.0) | 1471/1852/423/39 (38.9/48.9/11.2/1.0%) | 294/631/337/77 (22.0/47.1/25.2/5.7%) | p < 0.001 |

| FDA approved drugs for AD | 2685/70.9% | 935/69.8% | p = 0.443 |

| Anxiolytics (Yes/%) | 299/7.9% | 137/10.2% | p = 0.009 |

| Antidepressants (Yes/%) | 1308/34.6% | 525/39.2% | p = 0.002 |

| Antipsychotics (Yes/%) | 139/3.7% | 111/8.3% | p < 0.001 |

| Variable | No Motor Sign | At Least One Motor Sign | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original dataset | |||

| Episodic memory—immediate recall | 4.2 ± 3.5 | 3.7 ± 3.4 | p < 0.001 |

| Episodic memory—delayed recall | 1.9 ± 2.9 | 1.8 ± 2.9 | p = 0.251 |

| Attention | 9.6 ± 2.1 | 9.1 ± 2.2 | p < 0.001 |

| Processing speed | 67 ± 40 | 84 ± 42 | p < 0.001 |

| Executive function | 207 ± 87 | 238 ± 79 | p < 0.001 |

| Semantic verbal fluency | 11.0 ± 5.0 | 9.3 ± 5.2 | p < 0.001 |

| Confrontation naming | 19.7 ± 7.1 | 17.9 ± 7.2 | p < 0.001 |

| Imputed datasets | |||

| Episodic memory—immediate recall | 4.2 ± 3.5 | 3.8 ± 3.4 | p < 0.001 |

| Episodic memory—delayed recall | 1.9 ± 3.0 | 1.9 ± 2.9 | p = 0.561 |

| Attention | 9.6 ± 2.2 | 9.0 ± 2.7 | p < 0.001 |

| Processing speed | 69 ± 40 | 87 ± 42 | p < 0.001 |

| Executive function | 214 ± 90 | 239 ± 80 | p < 0.001 |

| Semantic verbal fluency | 11.0 ± 5.0 | 9.2 ± 5.3 | p < 0.001 |

| Confrontation naming | 19.6 ± 7.2 | 17.5 ± 7.4 | p < 0.001 |

| Original Dataset | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Domain | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

| Episodic memory—immediate recall | 1.003 | 0.964–1.043 | p = 0.900 |

| Episodic memory—delayed recall | 1.042 | 0.999–1.085 | p = 0.054 |

| Attention | 0.993 | 0.942–1.046 | p = 0.788 |

| Processing speed | 1.007 | 1.004–1.010 | p < 0.001 |

| Executive function | 1.002 | 1.001–1.004 | p = 0.003 |

| Semantic verbal fluency | 1.002 | 0.978–1.027 | p = 0.877 |

| Confrontation naming | 1.013 | 0.996–1.031 | p = 0.138 |

| Imputed datasets | |||

| Cognitive domain | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

| Episodic memory—immediate recall | 1.007 | 0.976–1.040 | p = 0.664 |

| Episodic memory—delayed recall | 1.049 | 1.012–1.086 | p = 0.009 |

| Attention | 0.961 | 0.924–1.000 | p = 0.051 |

| Processing speed | 1.006 | 1.003–1.008 | p < 0.001 |

| Executive function | 1.002 | 1.000–1.003 | p = 0.034 |

| Semantic verbal fluency | 0.991 | 0.972–1.011 | p = 0.381 |

| Confrontation naming | 1.018 | 1.004–1.031 | p = 0.009 |

| Cognitive Domain | Original Dataset | Imputed Datasets | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | LL | UL | p Value | OR | LL | UL | p Value | |

| Impaired chair rise | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 1.029 | 0.961 | 1.103 | 0.412 | 1.036 | 0.981 | 1.094 | 0.206 |

| Delayed recall | 1.052 | 0.977 | 1.132 | 0.177 | 1.035 | 0.974 | 1.099 | 0.268 |

| Attention | 1.069 | 0.978 | 1.169 | 0.140 | 0.983 | 0.921 | 1.048 | 0.591 |

| Processing speed | 1.005 | 1.000 | 1.010 | 0.053 | 1.004 | 1.001 | 1.008 | 0.017 |

| Executive function | 1.005 | 1.002 | 1.008 | <0.001 | 1.004 | 1.002 | 1.006 | 0.001 |

| Verbal fluency | 0.986 | 0.945 | 1.030 | 0.536 | 0.996 | 0.963 | 1.03 | 0.812 |

| Confrontation naming | 1.017 | 0.987 | 1.048 | 0.274 | 1.024 | 1.001 | 1.047 | 0.042 |

| Impaired posture-gait | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 1.058 | 0.982 | 1.140 | 0.136 | 1.059 | 0.995 | 1.127 | 0.070 |

| Delayed recall | 0.992 | 0.914 | 1.077 | 0.848 | 0.992 | 0.923 | 1.066 | 0.826 |

| Attention | 1.047 | 0.953 | 1.150 | 0.343 | 0.981 | 0.917 | 1.049 | 0.566 |

| Processing speed | 1.007 | 1.001 | 1.012 | 0.014 | 1.008 | 1.003 | 1.012 | 0.001 |

| Executive function | 1.001 | 0.998 | 1.004 | 0.431 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.002 | 0.871 |

| Verbal fluency | 1.010 | 0.965 | 1.058 | 0.660 | 1.005 | 0.974 | 1.038 | 0.753 |

| Confrontation naming | 0.986 | 0.955 | 1.018 | 0.386 | 1.007 | 0.982 | 1.032 | 0.597 |

| Postural instability | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 1.022 | 0.948 | 1.102 | 0.573 | 0.996 | 0.933 | 1.064 | 0.910 |

| Delayed recall | 1.025 | 0.946 | 1.111 | 0.547 | 1.046 | 0.977 | 1.120 | 0.195 |

| Attention | 0.961 | 0.873 | 1.057 | 0.414 | 0.93 | 0.863 | 1.003 | 0.059 |

| Processing speed | 1.006 | 1.001 | 1.012 | 0.023 | 1.006 | 1.001 | 1.010 | 0.011 |

| Executive function | 1.001 | 0.998 | 1.004 | 0.389 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.003 | 0.718 |

| Verbal fluency | 0.973 | 0.927 | 1.020 | 0.251 | 0.975 | 0.941 | 1.011 | 0.169 |

| Confrontation naming | 1.025 | 0.992 | 1.058 | 0.140 | 1.038 | 1.009 | 1.068 | 0.012 |

| Bradykinesia | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 1.050 | 0.988 | 1.115 | 0.115 | 1.036 | 0.989 | 1.085 | 0.140 |

| Delayed recall | 1.031 | 0.968 | 1.098 | 0.339 | 1.047 | 0.993 | 1.105 | 0.088 |

| Attention | 0.940 | 0.868 | 1.017 | 0.125 | 0.943 | 0.892 | 0.997 | 0.040 |

| Processing speed | 1.006 | 1.001 | 1.010 | 0.010 | 1.007 | 1.004 | 1.010 | <0.001 |

| Executive function | 1.002 | 1.000 | 1.004 | 0.083 | 1.001 | 0.999 | 1.003 | 0.169 |

| Verbal fluency | 1.008 | 0.971 | 1.046 | 0.684 | 0.985 | 0.955 | 1.017 | 0.361 |

| Confrontation naming | 0.992 | 0.966 | 1.019 | 0.576 | 1.003 | 0.985 | 1.021 | 0.763 |

| Rigidity | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 1.051 | 0.972 | 1.136 | 0.212 | 1.047 | 0.987 | 1.112 | 0.130 |

| Delayed recall | 1.011 | 0.932 | 1.098 | 0.786 | 1.013 | 0.945 | 1.085 | 0.716 |

| Attention | 1.032 | 0.930 | 1.145 | 0.555 | 0.947 | 0.879 | 1.021 | 0.155 |

| Processing speed | 1.006 | 1.000 | 1.012 | 0.042 | 1.004 | 0.998 | 1.009 | 0.164 |

| Executive function | 1.002 | 0.999 | 1.005 | 0.156 | 1.001 | 0.998 | 1.004 | 0.474 |

| Verbal fluency | 0.970 | 0.923 | 1.019 | 0.220 | 0.968 | 0.933 | 1.005 | 0.087 |

| Confrontation naming | 1.020 | 0.985 | 1.056 | 0.260 | 1.017 | 0.992 | 1.042 | 0.182 |

| Action-postural tremor | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 0.960 | 0.888 | 1.037 | 0.295 | 0.955 | 0.896 | 1.019 | 0.166 |

| Delayed recall | 1.066 | 0.986 | 1.151 | 0.107 | 1.058 | 0.989 | 1.131 | 0.104 |

| Attention | 0.970 | 0.874 | 1.077 | 0.570 | 0.952 | 0.881 | 1.028 | 0.208 |

| Processing speed | 0.999 | 0.992 | 1.005 | 0.708 | 1.001 | 0.996 | 1.006 | 0.799 |

| Executive function | 1.002 | 1.000 | 1.005 | 0.102 | 1.002 | 0.999 | 1.004 | 0.200 |

| Verbal fluency | 1.001 | 0.956 | 1.048 | 0.968 | 1.006 | 0.968 | 1.046 | 0.752 |

| Confrontation naming | 1.035 | 0.998 | 1.072 | 0.061 | 1.041 | 1.013 | 1.071 | 0.005 |

| Resting tremor | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 1.055 | 0.930 | 1.196 | 0.407 | 1.056 | 0.933 | 1.195 | 0.380 |

| Delayed recall | 1.025 | 0.897 | 1.172 | 0.714 | 1.030 | 0.907 | 1.168 | 0.647 |

| Attention | 1.009 | 0.857 | 1.187 | 0.918 | 1.046 | 0.928 | 1.177 | 0.463 |

| Processing speed | 1.007 | 0.998 | 1.016 | 0.134 | 1.003 | 0.995 | 1.010 | 0.492 |

| Executive function | 0.999 | 0.994 | 1.004 | 0.647 | 1.001 | 0.996 | 1.005 | 0.706 |

| Verbal fluency | 0.959 | 0.885 | 1.040 | 0.311 | 0.970 | 0.905 | 1.039 | 0.380 |

| Confrontation naming | 0.989 | 0.935 | 1.045 | 0.695 | 1.001 | 0.959 | 1.046 | 0.950 |

| Masked facies | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 1.020 | 0.896 | 1.162 | 0.763 | 1.091 | 0.989 | 1.202 | 0.081 |

| Delayed recall | 1.064 | 0.936 | 1.210 | 0.343 | 1.041 | 0.940 | 1.152 | 0.442 |

| Attention | 1.066 | 0.899 | 1.264 | 0.461 | 0.975 | 0.833 | 1.141 | 0.739 |

| Processing speed | 1.007 | 0.998 | 1.017 | 0.125 | 1.005 | 0.997 | 1.012 | 0.212 |

| Executive function | 1.002 | 0.997 | 1.007 | 0.337 | 1.002 | 0.996 | 1.008 | 0.437 |

| Verbal fluency | 1.008 | 0.932 | 1.091 | 0.834 | 1.001 | 0.943 | 1.062 | 0.983 |

| Confrontation naming | 1.018 | 0.960 | 1.080 | 0.551 | 1.025 | 0.985 | 1.066 | 0.228 |

| Hypophonia | ||||||||

| Immediate recall | 0.913 | 0.755 | 1.105 | 0.351 | 0.934 | 0.809 | 1.079 | 0.353 |

| Delayed recall | 1.214 | 1.029 | 1.432 | 0.022 | 1.070 | 0.897 | 1.276 | 0.451 |

| Attention | 0.851 | 0.664 | 1.092 | 0.206 | 0.83 | 0.715 | 0.964 | 0.016 |

| Processing speed | 1.009 | 0.996 | 1.022 | 0.183 | 1.001 | 0.993 | 1.009 | 0.770 |

| Executive function | 1.004 | 0.995 | 1.012 | 0.426 | 1.001 | 0.996 | 1.007 | 0.620 |

| Verbal fluency | 1.006 | 0.888 | 1.141 | 0.923 | 0.979 | 0.899 | 1.066 | 0.617 |

| Confrontation naming | 0.980 | 0.901 | 1.066 | 0.642 | 0.983 | 0.938 | 1.029 | 0.460 |

| Cognitive Domain | Original Dataset | Imputed Datasets | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | LL | UL | p Value | OR | LL | UL | p Value | |

| Sex—male sex was used as reference | ||||||||

| Female sex by processing speed | 1.001 | 0.995 | 1.006 | 0.813 | 0.999 | 0.995 | 1.003 | 0.650 |

| Female sex by executive function | 0.999 | 0.997 | 1.002 | 0.647 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.002 | 0.945 |

| Race—Caucasian race was used as reference | ||||||||

| African American race by processing speed | 0.999 | 0.991 | 1.007 | 0.766 | 1.003 | 0.997 | 1.009 | 0.365 |

| Asian race by processing speed | 1.004 | 0.975 | 1.035 | 0.773 | 1.004 | 0.986 | 1.023 | 0.667 |

| Other race by processing speed | 0.997 | 0.981 | 1.014 | 0.733 | 0.993 | 0.981 | 1.006 | 0.277 |

| African American race by executive function | 1.000 | 0.995 | 1.005 | 0.881 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.004 | 0.849 |

| Asian race by executive function | 1.002 | 0.989 | 1.015 | 0.800 | 1.004 | 0.993 | 1.014 | 0.481 |

| Other race by executive function | 1.000 | 0.988 | 1.013 | 0.957 | 1.002 | 0.994 | 1.011 | 0.619 |

| APOE—APOE2 was used as reference | ||||||||

| APOE3 by processing speed | 0.993 | 0.983 | 1.003 | 0.165 | 0.996 | 0.989 | 1.004 | 0.315 |

| APOE4 by processing speed | 0.994 | 0.984 | 1.004 | 0.218 | 0.997 | 0.990 | 1.005 | 0.483 |

| APOE3 by executive function | 1.001 | 0.997 | 1.006 | 0.532 | 1.001 | 0.996 | 1.005 | 0.797 |

| APOE4 by executive function | 1.003 | 0.998 | 1.007 | 0.227 | 1.002 | 0.997 | 1.006 | 0.448 |

| Years of age | ||||||||

| Age by processing speed | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.219 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.190 |

| Age by executive function | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.499 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.411 |

| Years of formal education | ||||||||

| Education by processing speed | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.090 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.331 |

| Education by executive function | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 0.072 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 0.350 |

| GDS | ||||||||

| GDS by processing speed | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.001 | 0.705 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.287 |

| GDS by executive function | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 0.155 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 0.113 |

| NPS—without NPS was used as reference | ||||||||

| Mild NPS by processing speed | 0.999 | 0.991 | 1.007 | 0.825 | 1.002 | 0.996 | 1.009 | 0.500 |

| Moderate-severe NPS by processing speed | 1.000 | 0.992 | 1.008 | 0.950 | 1.002 | 0.996 | 1.008 | 0.547 |

| Mild NPS by executive function | 1.001 | 0.998 | 1.005 | 0.480 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 1.004 | 0.917 |

| Moderate-severe NPS by executive function | 1.002 | 0.998 | 1.006 | 0.265 | 1.001 | 0.997 | 1.004 | 0.737 |

| CDR—the very mild stage was used as reference | ||||||||

| Mild stage by processing speed | 1.001 | 0.995 | 1.008 | 0.671 | 1.000 | 0.995 | 1.005 | 0.993 |

| Moderate stage by processing speed | 0.990 | 0.981 | 0.999 | 0.027 | 0.995 | 0.988 | 1.002 | 0.177 |

| Severe stage by processing speed | 0.624 | 0.000 | N/A | 0.999 | 0.983 | 0.959 | 1.007 | 0.154 |

| Mild stage by executive function | 1.000 | 0.997 | 1.003 | 0.897 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 1.003 | 0.907 |

| Moderate stage by executive function | 1.000 | 0.995 | 1.006 | 0.889 | 0.998 | 0.994 | 1.002 | 0.312 |

| Severe stage by executive function | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.000 | 0.985 | 1.015 | 0.993 |

| Anxiolytics—the group without intake was used as reference | ||||||||

| Anxiolytics by processing speed | 1.000 | 0.990 | 1.010 | 0.980 | 1.002 | 0.995 | 1.009 | 0.514 |

| Anxiolytics by executive function | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.004 | 0.944 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.004 | 0.944 |

| Antidepressants—the group without intake was used as reference | ||||||||

| Antidepressants by processing speed | 1.004 | 0.998 | 1.009 | 0.228 | 1.002 | 0.998 | 1.006 | 0.318 |

| Antidepressants by executive function | 1.000 | 0.997 | 1.002 | 0.757 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.002 | 0.951 |

| Antipsychotics—the group without intake was used as reference | ||||||||

| Antipsychotics by processing speed | 0.999 | 0.986 | 1.012 | 0.886 | 1.001 | 0.993 | 1.008 | 0.876 |

| Antipsychotics by executive function | 1.003 | 0.996 | 1.011 | 0.408 | 1.001 | 0.994 | 1.008 | 0.837 |

| FDA approved drugs for AD—the group without intake was used as reference | ||||||||

| Drugs for AD by processing speed | 0.996 | 0.990 | 1.002 | 0.208 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.005 | 0.889 |

| Drugs for AD by executive function | 1.002 | 0.999 | 1.005 | 0.131 | 1.001 | 0.998 | 1.003 | 0.610 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liampas, I.; Siokas, V.; Marogianni, C.; Tsika, A.; Dastamani, M.; Stamati, P.; Dardiotis, E. Associations Between Cognitive Performance and Motor Signs in Older Adults with Alzheimer’s Dementia. Medicina 2025, 61, 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122116

Liampas I, Siokas V, Marogianni C, Tsika A, Dastamani M, Stamati P, Dardiotis E. Associations Between Cognitive Performance and Motor Signs in Older Adults with Alzheimer’s Dementia. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122116

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiampas, Ioannis, Vasileios Siokas, Chrysoula Marogianni, Antonia Tsika, Metaxia Dastamani, Polyxeni Stamati, and Efthimios Dardiotis. 2025. "Associations Between Cognitive Performance and Motor Signs in Older Adults with Alzheimer’s Dementia" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122116

APA StyleLiampas, I., Siokas, V., Marogianni, C., Tsika, A., Dastamani, M., Stamati, P., & Dardiotis, E. (2025). Associations Between Cognitive Performance and Motor Signs in Older Adults with Alzheimer’s Dementia. Medicina, 61(12), 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122116