Prognostic Significance of Ultralow (UL) Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Single Institution and Tertiary Cancer Center Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

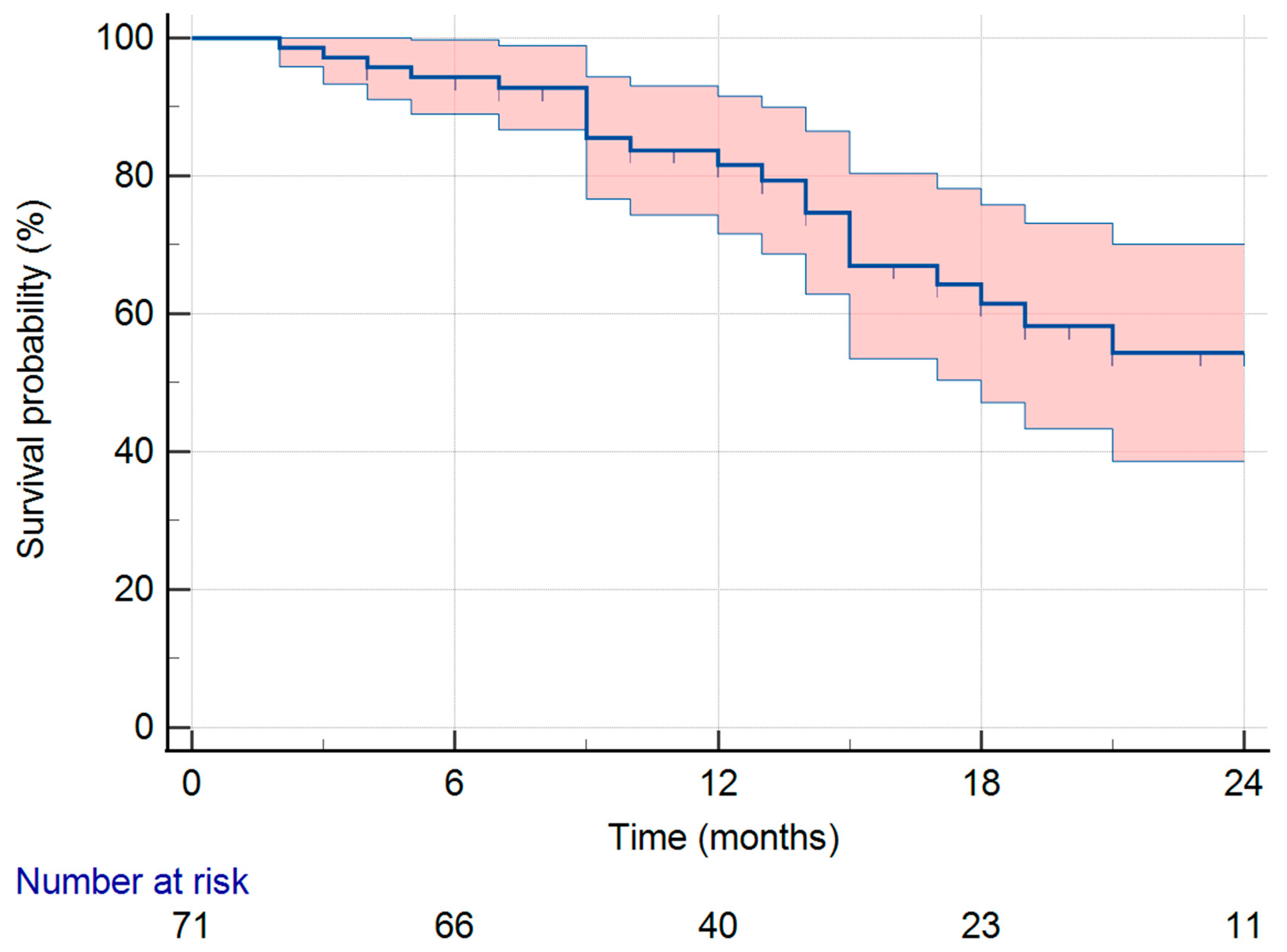

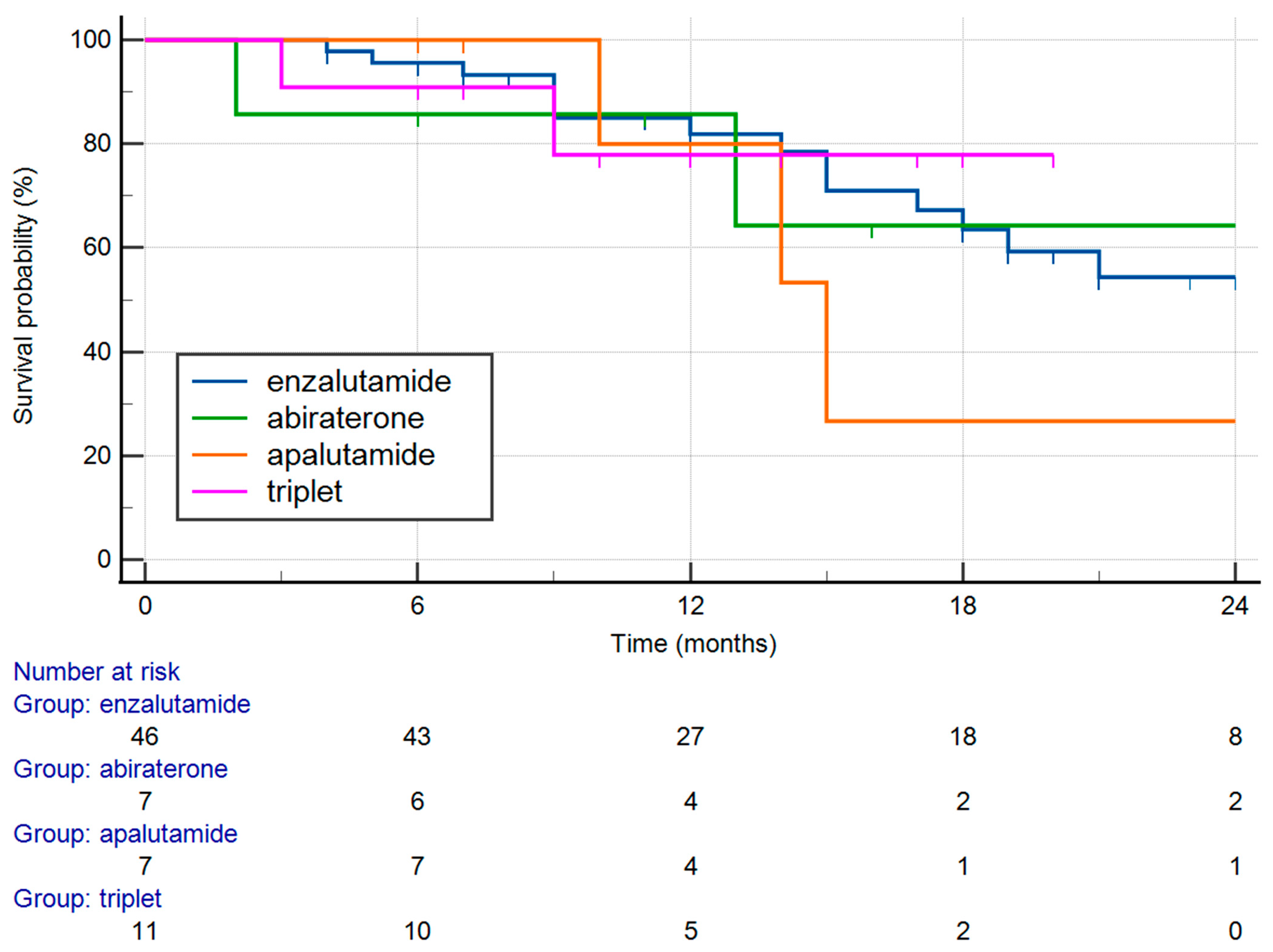

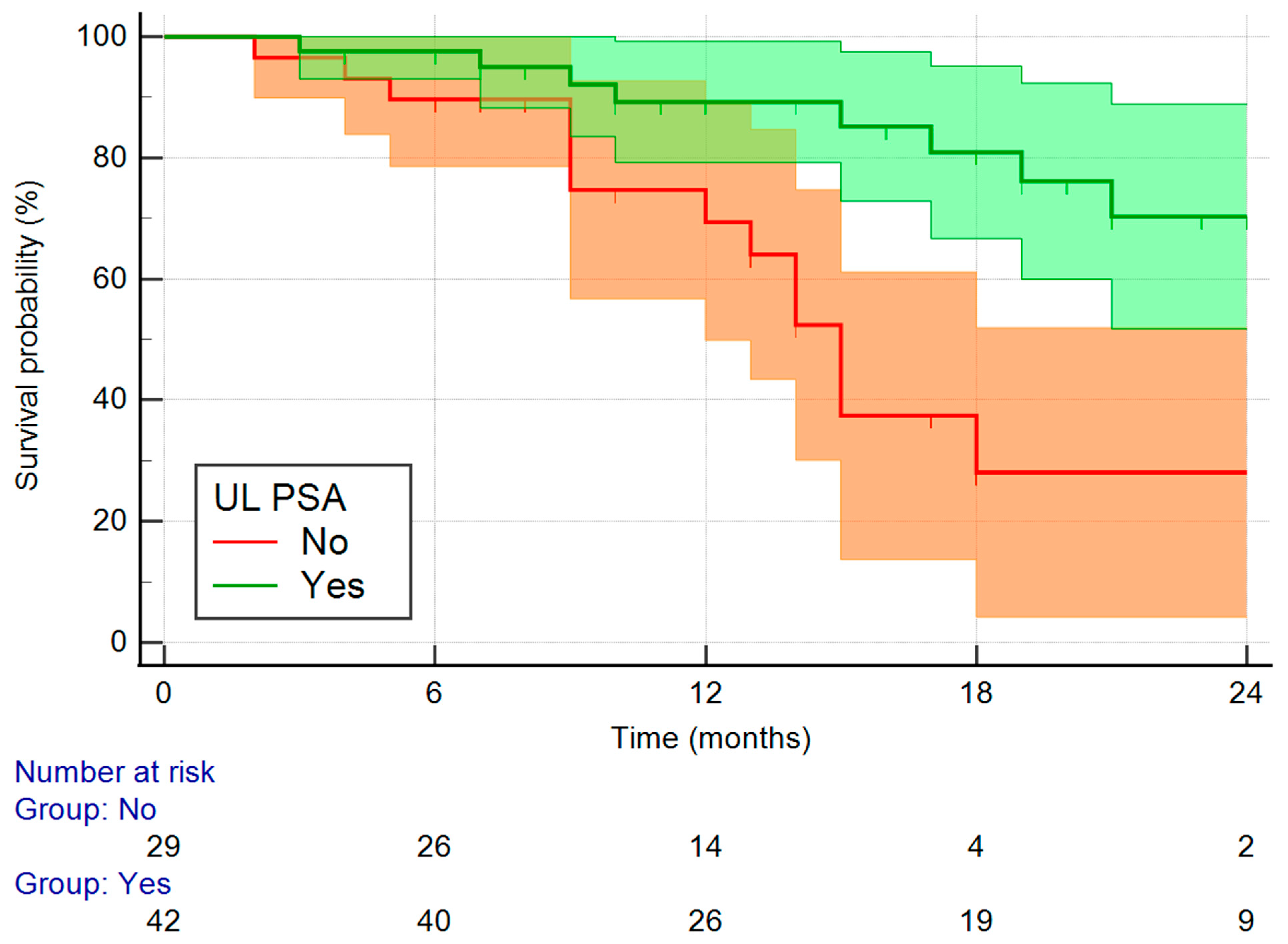

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Radiographic surveillance remains essential even in UL PSA achievers, as a subset may develop non-biochemical progression.

- Risk stratification tools incorporating imaging, baseline clinical characteristics (e.g., high-volume/high risk disease), and genomic data may help identify at-risk patients.

- Alternative endpoints: trials and clinical practice should use other endpoints that include imaging and symptomatic clinical progression, not just PSA dynamic.

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSA | prostate-specific antigen |

| mHSPC | metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer |

| mCRPC | metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| ARTA | androgen receptor-targeted agents |

| ADT | androgen deprivation therapy |

| GnRH | gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| OS | overall survival |

| rPFS | radiographic progression-free survival |

| cfDNA | cell free deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

References

- Chi, K.N.; Agarwal, N.; Bjartell, A.; Chung, B.H.; Pereira de Santana Gomes, A.J.; Uemura, H.; Ye, D.; Given, R.; Miladinovic, B.; Lopez-Gitlitz, A.; et al. Apalutamide plus androgen-deprivation therapy for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2294–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Petrylak, D.P.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Villers, A.; Shore, N.D.; Hussain, M.; Karrison, T.; Gross, M.; Clarke, N.W.; et al. ARCHES: A randomized, phase III study of enzalutamide plus androgen deprivation therapy versus placebo plus androgen deprivation therapy in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2974–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Tran, N.; Fein, L.; Matsubara, N.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ye, D.; Feyerabend, S.; Protheroe, A.; et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merseburger, A.S.; Kuczyk, M.A.; Mertens, C.; Heinzer, H.; Herold, C.J.; Quhal, F.; Yildirim, M.A.; Bach, D.; Dork, T.; Gakis, G.; et al. Post-hoc analysis of the TITAN trial: Ultralow PSA response with apalutamide plus androgen-deprivation therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2024, 133, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Abad, A.; Belmonte, M.; Ramírez Backhaus, M.; Server Gómez, G.; Cao Avellaneda, E.; Moreno Alarcón, C.; López Cubillana, P.; Yago Giménez, P.; de Pablos Rodríguez, P.; Juan Fita, M.J.; et al. Ultralow prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and improved oncological outcomes in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) patients treated with Apalutamide: A real-world multicentre study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosso, D.; Pagliuca, M.; Sonpavde, G.; Pond, G.; Lucarelli, G.; Rossetti, S.; Facchini, G.; Scagliarini, S.; Cartenì, G.; Daniele, B.; et al. PSA Declines and Survival in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Treated with Enzalutamide: A Retrospective Case-Report Study. Medicine 2017, 96, e6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, I.D.; Martin, A.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Begbie, S.; Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Coskinas, X.; Frydenberg, M.; Hague, W.E.; Horvath, L.G.; et al. Enzalutamide with Standard First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Carducci, M.; Liu, G.; Jarrard, D.F.; Eisenberger, M.; Wong, Y.N.; Hahn, N.; Kohli, M.; Cooney, M.M.; et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, A.A.; Petrylak, D.P.; Iguchi, T.; Shore, N.D.; Villers, A.; Gomez-Veiga, F.; Alcaraz, A.; Alekseev, B.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Holzbeierlein, J.; et al. Enzalutamide and Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of the ARCHES Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2833622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.-W.; Uemura, H.; Chung, B.H.; Suzuki, H.; Mundle, S.; Bhaumik, A.; Singh, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Agarwal, N.; Chi, K.N.; et al. Prostate-Specific Antigen Kinetics in Asian Patients with Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Treated with Apalutamide in the TITAN Trial: A Post Hoc Analysis. Int. J. Urol. 2025, 32, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryce, A.H.; Alumkal, J.J.; Armstrong, A.; Higano, C.S.; Iversen, P.; Sternberg, C.N.; Rathkopf, D.; Loriot, Y.; de Bono, J.; Tombal, B.; et al. Radiographic progression with non-rising PSA in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Post hoc analysis of PREVAIL. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017, 20, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, I.D.; Martin, A.J.; Zielinski, R.R.; Thomson, A.; Tan, T.H.; Sandhu, S.; Reaume, M.N.; Pook, D.W.; Parnis, F.; North, S.A.; et al. Radiographic Progression without PSA Progression in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Retrospective Analysis from the ENZAMET Trial (ANZUP 1304). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. 4), 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Bhaumik, A.; Agarwal, N.; Shotts, K.M.; Lopez-Gitlitz, A.; McCarthy, S.; Mundle, S.D.; Chi, K.N.; Small, E.J. Radiographic Progression without PSA Progression in Advanced Prostate Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 (Suppl. 5), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Mottet, N.; Iguchi, T.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Villers, A.; Alcaraz, A.; Alekseev, B.; Shore, N.D.; Gomez-Veiga, F.; et al. Radiographic Progression in the Absence of Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Progression in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Post Hoc Analysis of ARCHES. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40 (Suppl. 16), 5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuokaya, W.; Yanagisawa, T.; Mori, K.; Urabe, F.; Rajwa, P.; Briganti, A.; Shariat, S.F.; Kimura, T. Radiographic Progression without Corresponding Prostate-Specific Antigen Progression in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Receiving Apalutamide: Secondary Analysis of the TITAN Trial. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, N.D.; de Bono, J.S.; Spears, M.R.; Clarke, N.W.; Mason, M.D.; Dearnaley, D.P.; Ritchie, A.W.S.; Amos, C.L.; Gilson, C.; Jones, R.J.; et al. Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Corral, R.; De Pablos-Rodríguez, P.; Bardella-Altarriba, C.; Vera-Ballesteros, F.J.; Abella-Serra, A.; Rodríguez-Part, V.; Martínez-Corral, M.E.; Picola-Brau, N.; López-Abad, A.; Gómez-Ferrer, Á.; et al. PSA Kinetics and Predictors of PSA Response in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Treated with Androgen Receptor Signaling Inhibitors. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 43, 527.e9–527.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Martin, A.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Begbie, S.; Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Coskinas, X.; Frydenberg, M.; Hague, W.E.; Horvath, L.G.; et al. Overall Survival of Men with Metachronous Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Treated with Enzalutamide and Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, K.N.; Agarwal, N.; Bjartell, A.; Chung, B.H.; Pereira de Santana Gomes, A.J.; Given, R.; Juárez Soto, Á.; Merseburger, A.S.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Uemura, H.; et al. Apalutamide for Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 71 (49–94) |

| Median iPSA (range), ng/mL | 87 (1.5–6903) |

| Gleason score (GS) | |

| <7 | 25 (35.2%) |

| ≥8 | 46 (64.8%) |

| Disease volume | |

| Low | 15 (21.1%) |

| High | 56 (78.9%) |

| Metastases timing | |

| Synchronous | 48 (67.6%) |

| Metachronous | 23 (32.4%) |

| UL PSA | 42 (59.2%) |

| Covariate | b | SE | Wald | p | Exp(b) | 95% CI of Exp(b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years (median) | −1.0504 | 0.4813 | 4.7639 | 0.0291 | 0.3498 | 0.1362 to 0.8984 |

| Metastases timing (synchronous vs. metachronous | −0.2732 | 0.5471 | 0.2494 | 0.6175 | 0.7609 | 0.2604 to 2.2237 |

| Disease volume (low vs. high) | −0.7077 | 0.6844 | 1.0691 | 0.3011 | 0.4928 | 0.1288 to 1.8848 |

| UL PSA | −1.8156 | 0.5235 | 12.0297 | 0.0005 | 0.1627 | 0.0583 to 0.4540 |

| Variable | Non-UL PSA | UL PSA | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years | 0.0190 | ||

| <71 | 9 | 25 | |

| >71 | 20 | 17 | |

| GS | 0.1070 | ||

| <7 | 7 | 18 | |

| ≥8 | 22 | 24 | |

| PSA median | 0.318 | ||

| <87 | 8 | 26 | |

| >87 | 21 | 16 | |

| Metastatic pattern | 0.0244 | ||

| Metachronous | 5 | 18 | |

| Synchronous | 24 | 24 | |

| Disease volume | 0.0154 | ||

| Low | 2 | 13 | |

| High | 27 | 29 | |

| Type of therapy | 0.715 | ||

| Enzalutamide | 18 | 28 | |

| Abiraterone | 4 | 3 | |

| Apalutamide | 2 | 5 | |

| Triplet | 5 | 6 |

| Covariate | Coefficient | SE | Wald | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years (median) | −1.88853 | 0.68060 | 7.6995 | 0.0055 |

| Gleason score (<7 vs. ≤8) | −0.28438 | 0.63290 | 0.2019 | 0.6532 |

| iPSA_(median) | −1.22873 | 0.81816 | 2.2555 | 0.1331 |

| GhRh vs. bilateral orchiectomy | 0.19384 | 0.63967 | 0.09183 | 0.7619 |

| Metastases timing (synchronous vs. metachronous | −0.59124 | 0.85286 | 0.4806 | 0.4882 |

| Disease volume (low vs. high) a | −0.89503 | 0.92733 | 0.9316 | 0.3345 |

| Treatment type | −0.12416 | 0.26305 | 0.2228 | 0.6369 |

| Constant | 5.12870 | 2.32747 | 4.8556 | 0.0276 |

| Years | De Novo mHSPC | Gleason Score | Grade Group | iPSA | Treatment | Lowest PSA | Survival (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56 | Yes | 4 + 4 | 4 | 114 | apalutamide | 0 | 15 |

| 68 | Yes | 4 + 4 | 4 | 86.54 | enzalutamide | 0.18 | 22 |

| 71 | No | 4 + 4 | 4 | 4.66 | enzalutamide | <0.01 | 17 |

| 68 | No | 3 + 5 | 4 | 27 | apalutamide | <0.01 | 10 |

| 60 | Yes | 4 + 4 | 4 | 709.8 | enzalutamide | 0.2 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suton, P.; Gregov, V. Prognostic Significance of Ultralow (UL) Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Single Institution and Tertiary Cancer Center Experience. Medicina 2025, 61, 2110. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122110

Suton P, Gregov V. Prognostic Significance of Ultralow (UL) Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Single Institution and Tertiary Cancer Center Experience. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2110. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122110

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuton, Petar, and Višnja Gregov. 2025. "Prognostic Significance of Ultralow (UL) Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Single Institution and Tertiary Cancer Center Experience" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2110. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122110

APA StyleSuton, P., & Gregov, V. (2025). Prognostic Significance of Ultralow (UL) Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Single Institution and Tertiary Cancer Center Experience. Medicina, 61(12), 2110. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122110