Impact of Distributing Test Result Reports for Chronic Viral Hepatitis on Awareness of Hepatitis Testing Among Non-Specialist Physicians

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Pre-Analysis of the Status Trends of Patients with Hepatitis Virus Tests

2.2. Preparation and Distribution of the Hepatitis Virus Test Result Reports

2.3. Patients and Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

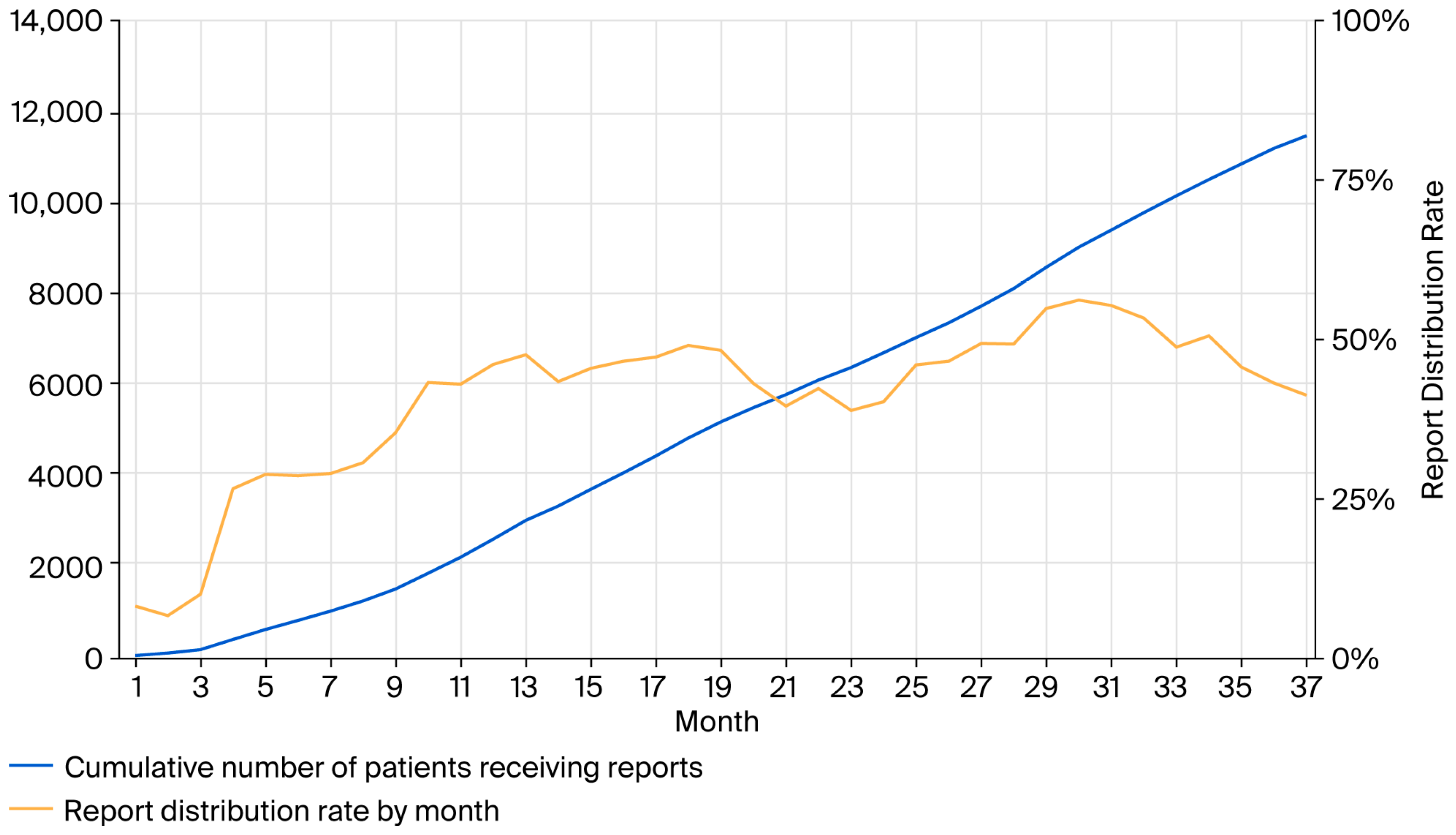

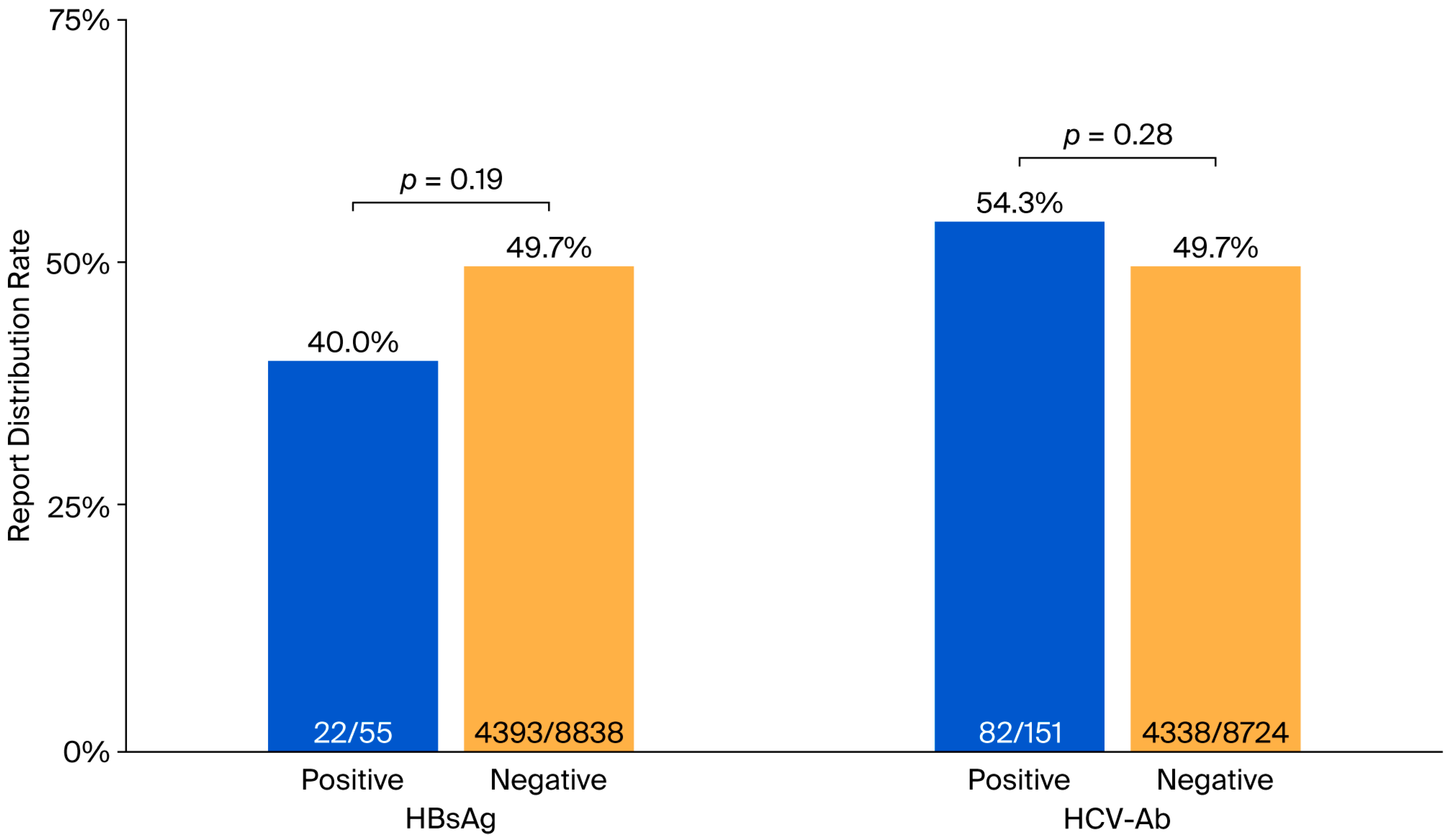

3.1. Trends in the Distribution of the Hepatitis Virus Test Result Reports

3.2. Characteristics of the Pre- and Post-Distribution Groups

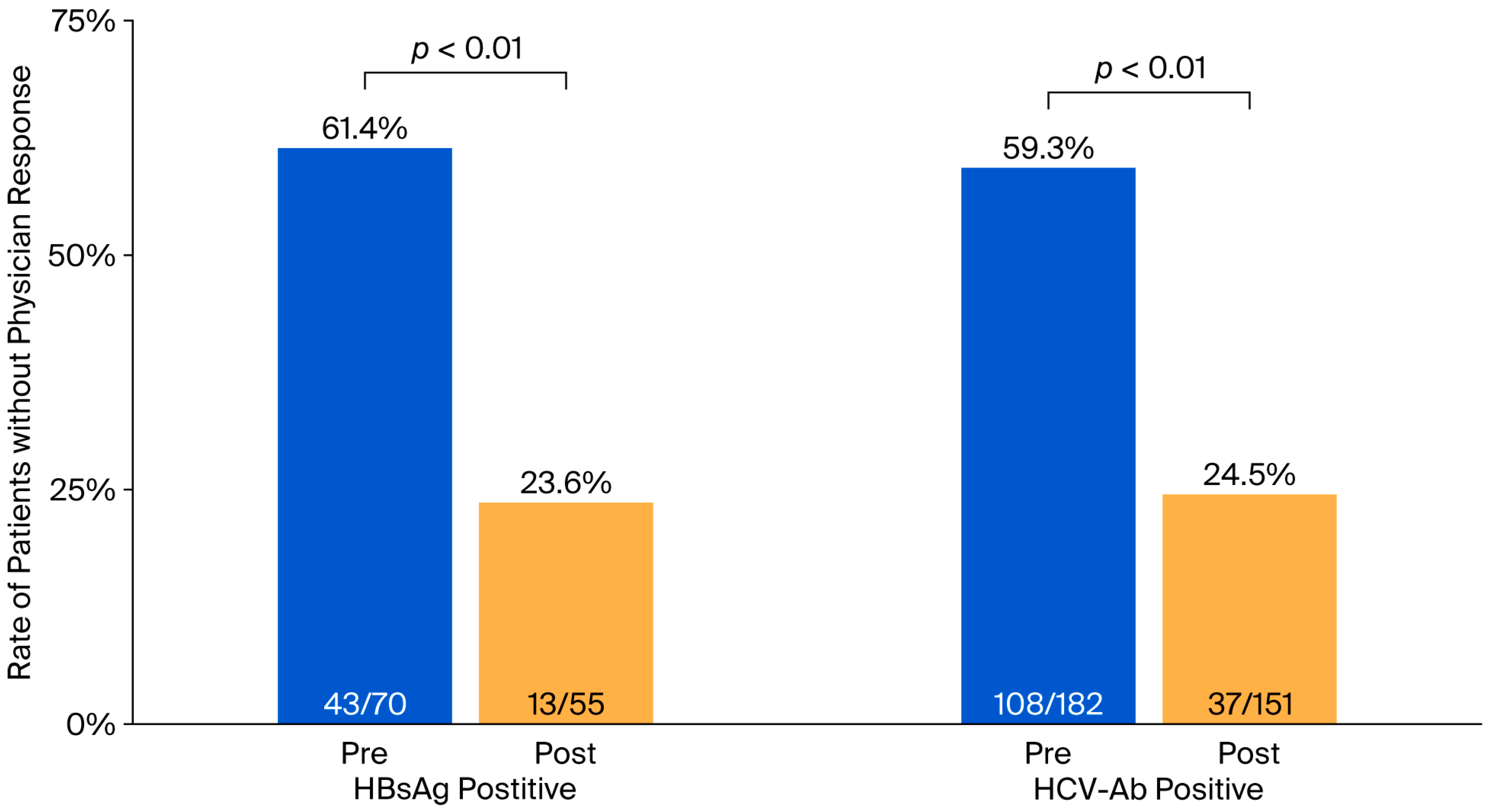

3.3. Impact of Hepatitis Virus Test Result Report Distribution on Non-Specialist Physicians’ Management of Test-Positive Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations:

| HBsAg | hepatitis B virus surface antigen |

| HCV-Ab | hepatitis C virus antibody |

References

- Bixler, D.; Barker, L.; Lewis, K.; Peretz, L.; Teshale, E. Prevalence and awareness of Hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: January 2017–March 2020. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Z.Z.; Teo, J.S.; Tan, A.C.; Lim, T.O. Awareness and treatment of chronic hepatitis B in Malaysia-findings from a community-based screening campaign. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denniston, M.M.; Klevens, R.M.; McQuillan, G.M.; Jiles, R.B. Awareness of infection, knowledge of hepatitis C, and medical follow-up among individuals testing positive for hepatitis C: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2008. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1652–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valerio, H.; Conway, A.; Alavi, M.; Treloar, C.; Silk, D.; Murray, C.; Henderson, C.; Amin, J.; Read, P.; Degenhardt, L.; et al. Awareness of hepatitis C virus infection status among people who inject drugs in a setting of universal direct-acting antiviral therapy: The ETHOS Engage study. Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 110, 103876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Clark, R.; Tu, P.; Tu, R.; Hsu, Y.J.; Nien, H.C. The disconnect in hepatitis screening: Participation rates, awareness of infection status, and treatment-seeking behavior. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 010426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isunju, J.B.; Wafula, S.T.; Ndejjo, R.; Nuwematsiko, R.; Bakkabulindi, P.; Nalugya, A.; Muleme, J.; Kimara, W.K.; Kibira, S.P.S.; Nakiggala, J.; et al. Awareness of hepatitis B post-exposure prophylaxis among healthcare providers in Wakiso district, Central Uganda. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargin, Z.G. Awareness of chronic hepatitis C in the Western Black Sea Region. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 7827–7832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, H.; Tanaka, J. National project for the management of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2005, 102, 1123–1131. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, J.; Akita, T.; Ohisa, M.; Sakamune, K.; Ko, K.; Uchida, S.; Satake, M. Trends in the total numbers of HBV and HCV carriers in Japan from 2000 to 2011. J. Viral Hepat. 2018, 25, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, J.; Akita, T.; Ko, K.; Miura, Y.; Satake, M.; Epidemiological Research Group on Viral Hepatitis and its Long-term Course, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Countermeasures against viral hepatitis B and C in Japan: An epidemiological point of view. Hepatol. Res. 2019, 49, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Combating Hepatitis B and C to Reach Elimination by 2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/combating-hepatitis-b-and-c-to-reach-elimination-by-2030 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Mostert, M.C.; Richardus, J.H.; de Man, R.A. Referral of chronic hepatitis B patients from primary to specialist care: Making a simple guideline work. J. Hepatol. 2004, 41, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, V.D.; Do, A.; Nguyen, N.H.; Kim, L.H.; Trinh, H.N.; Nguyen, H.A.; Nguyen, K.K.; Nguyen, M.; Huynh, A.; Nguyen, M.H. Long-term follow-up and suboptimal treatment rates of treatment-eligible chronic hepatitis B patients in diverse practice settings: A gap in linkage to care. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015, 2, e000060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, C.S.; Ko, O.; Lee, S.; McMenamin, J. Long term outcome of a community-based hepatitis B awareness campaign: Eight-year follow-up on linkage to care (LTC) in HBV infected individuals. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, S.D.; Chang, E.T.; Le, P.V.; Prapong, W.; Kiernan, M.; So, S.K. The Jade Ribbon Campaign: A model program for community outreach and education to prevent liver cancer in Asian Americans. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2009, 11, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, G.; Cabral, R.; Patterson, M.; Schenbachler, B.T.; Bedell, D.; Smith, B.D.; Vellozzi, C.; Beckett, G.A. Early Identification and Linkage to Care for People with Chronic HBV and HCV Infection: The HepTLC Initiative. Public Health Rep. 2016, 131 (Suppl. S2), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, M.; Sawabe, M.; Aoyagi, H.; Watake, K.; Watashi, K.; Hattori, S.; Kawabe, N.; Yoshioka, K.; Tanaka, J.; Muramatsu, M.; et al. Development of an intervention system for linkage-to-care and follow-up for hepatitis B and C virus carriers. Hepatol. Int. 2022, 16, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abara, W.E.; Qaseem, A.; Schillie, S.; McMahon, B.J.; Harris, A.M.; High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B Vaccination, Screening, and Linkage to Care: Best Practice Advice From the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, J.M.; McIntyre, P.G.; McLeod, S.; Nathwani, D.; Dillon, J.F. The impact of a managed care network on attendance, follow-up and treatment at a hepatitis C specialist centre. J. Viral Hepat. 2010, 17, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pre * (n = 9365) | Post ** (n = 8923) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) *,3 | 71 (0–105) | 72 (0–103) |

| Male | 55.3% | 56.0% |

| Tested only HBsAg | 0.68% | 0.51% |

| Tested only HCV-Ab | 0.31% | 0.31% |

| Tested both tests | 99.0% | 99.2% |

| Test-positive | ||

| HBsAg-positive | 0.73% | 0.55% |

| HCV-Ab-positive | 1.94% | 1.70% |

| Report distributed | 49.7% | |

| Among tested HBsAg | 49.5% | |

| Among tested HCV-Ab | 49.8% | |

| Test-positive (among reports distributed) | ||

| HBsAg-positive | 0.50% | |

| HCV-Ab-positive | 1.86% | |

| HBsAg-Positive | HCV-Ab-Positive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre * (n = 70) | Post ** (n = 55) | p-Value | Pre * (n = 182) | Post ** (n = 151) | p-Value | |

| Male | 50.0% | 47.3% | 0.85 | 56.0% | 58.3% | 0.74 |

| Age (years) *,3 | 72 (34–89) | 73 (44–93) | 0.90 | 79 (26–98) | 77 (41–100) | 0.79 |

| Deceased or terminal cancer cases | 8.6% | 9.1% | 1 | 11.0% | 15.2% | 0.26 |

| Report distributed | - | 40.0% | - | 54.3% | ||

| Referred to gastroenterologist *,4 | 11.4% | 34.5% | <0.01 | 7.7% | 25.2% | <0.01 |

| Further tests performed *,5 | 7.1% | 1.8% | 0.23 | 7.7% | 12.6% | 0.15 |

| Clinical cure or ongoing treatment confirmed *,6 | 4.3% | 18.2% | 0.02 | 16.5% | 28.5% | 0.01 |

| Results documented in medical records *,7 | 34.3% | 61.8% | <0.01 | 25.3% | 39.1% | <0.01 |

| Without physician responses | 61.4% | 23.6% | <0.01 | 59.3% | 24.5% | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Itakura, J.; Ito, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Aoki, Y.; Takamura, K.; Yajima, K.; Miyahara, R.; Uetake, H.; Otomo, Y. Impact of Distributing Test Result Reports for Chronic Viral Hepatitis on Awareness of Hepatitis Testing Among Non-Specialist Physicians. Medicina 2025, 61, 2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112067

Itakura J, Ito Y, Suzuki T, Aoki Y, Takamura K, Yajima K, Miyahara R, Uetake H, Otomo Y. Impact of Distributing Test Result Reports for Chronic Viral Hepatitis on Awareness of Hepatitis Testing Among Non-Specialist Physicians. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112067

Chicago/Turabian StyleItakura, Jun, Yutaka Ito, Takashi Suzuki, Yukiko Aoki, Kaori Takamura, Kenji Yajima, Rie Miyahara, Hiroyuki Uetake, and Yasuhiro Otomo. 2025. "Impact of Distributing Test Result Reports for Chronic Viral Hepatitis on Awareness of Hepatitis Testing Among Non-Specialist Physicians" Medicina 61, no. 11: 2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112067

APA StyleItakura, J., Ito, Y., Suzuki, T., Aoki, Y., Takamura, K., Yajima, K., Miyahara, R., Uetake, H., & Otomo, Y. (2025). Impact of Distributing Test Result Reports for Chronic Viral Hepatitis on Awareness of Hepatitis Testing Among Non-Specialist Physicians. Medicina, 61(11), 2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112067