1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was declared on 11 March 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO) following a rapid global increase in cases [

1]. Mortality in COVID-19 often resulted from acute respiratory distress syndrome or from the exacerbation of pre-existing comorbidities, especially cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), which represented one of the most important risk factors for severe or fatal outcomes [

2]. Studies conducted in China and Europe showed that up to 40% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients had pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, and many presented elevated cardiac biomarkers, arrhythmias, or heart failure as complications [

3].

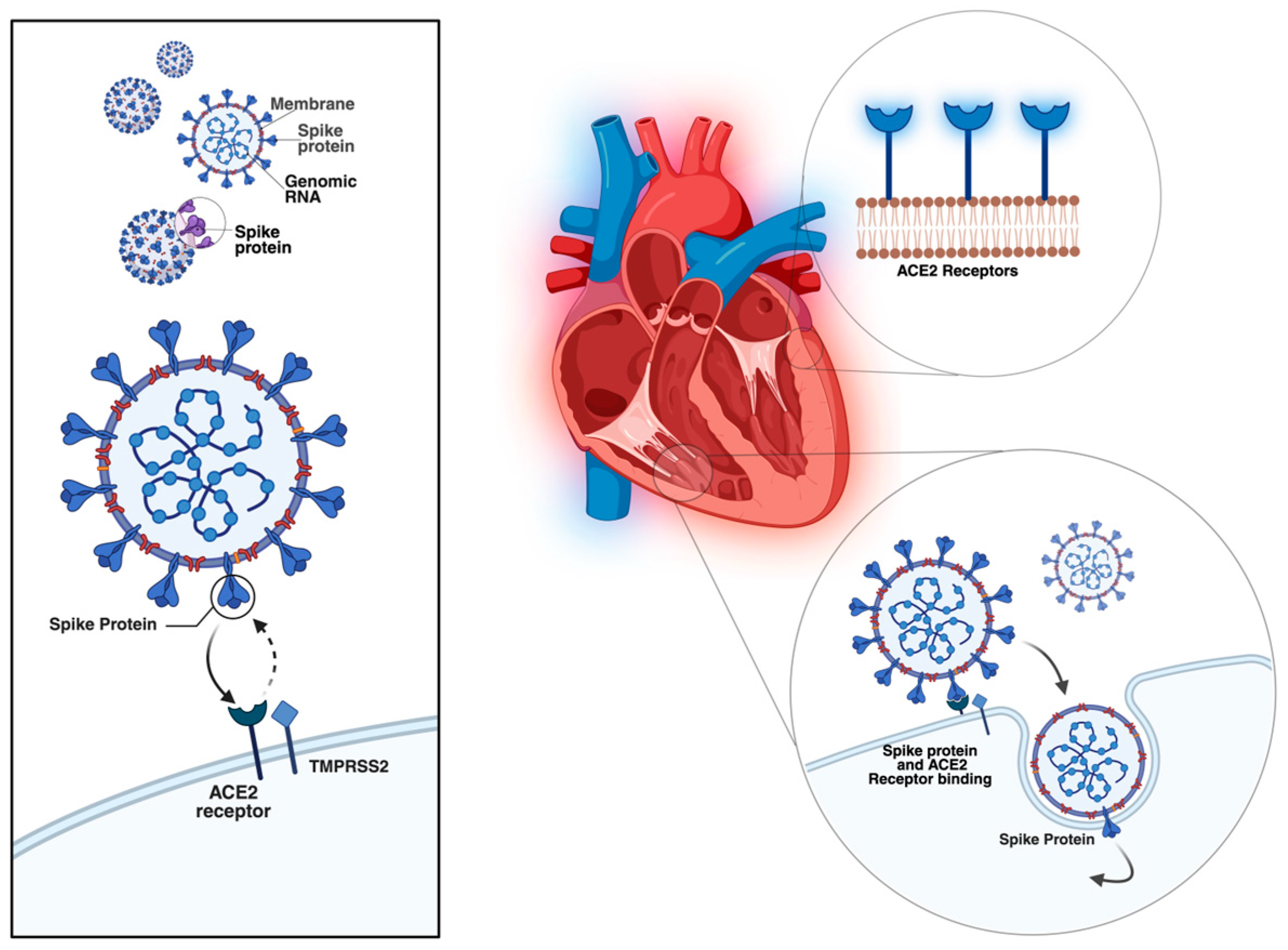

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the cardiac involvement in COVID-19. Direct myocardial injury occurs through SARS-CoV-2 binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, highly expressed in myocardial pericytes, which may lead to microcirculatory dysfunction and cardiac remodelling [

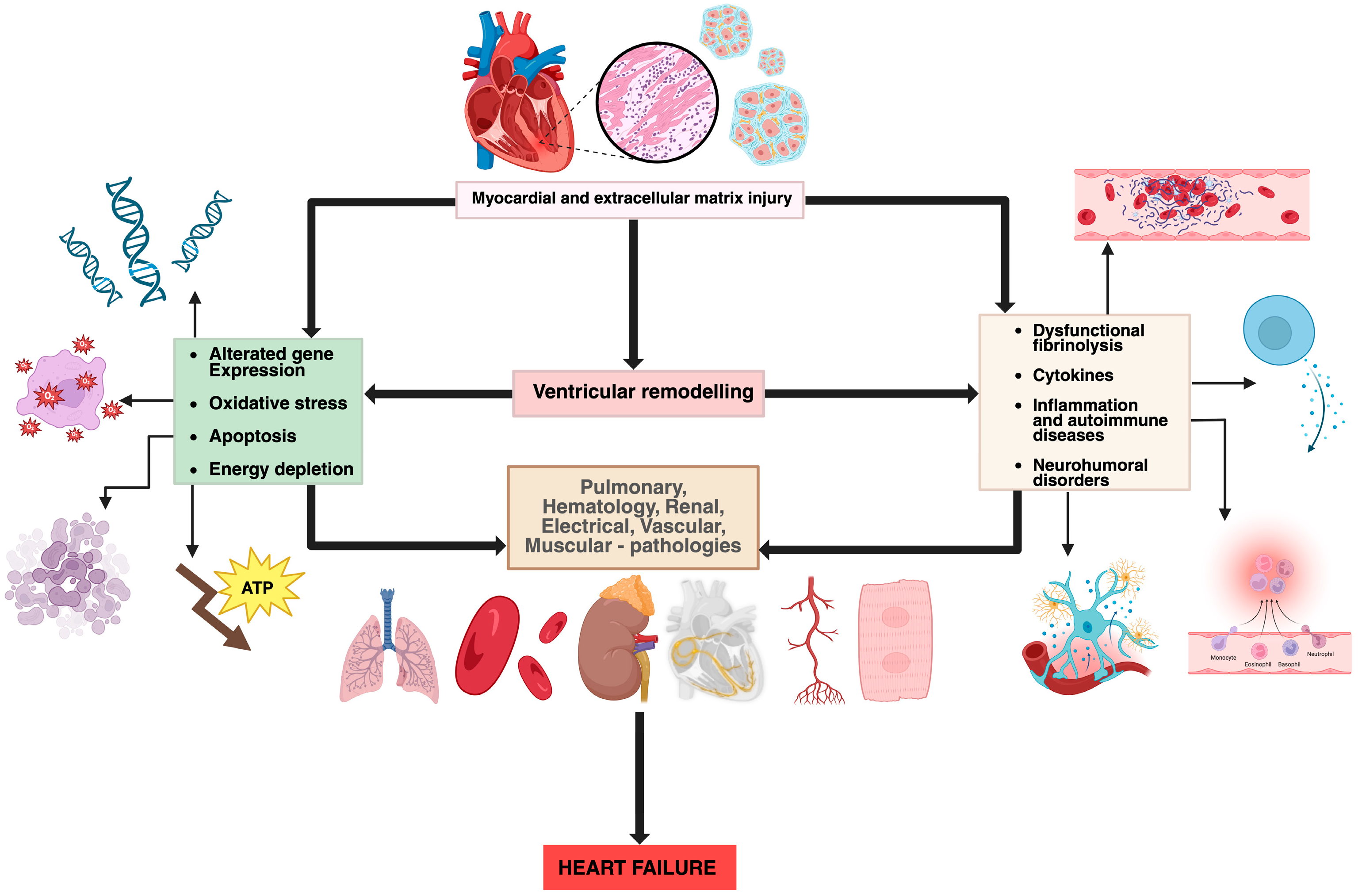

4]. In addition, indirect injury mechanisms include systemic inflammation, cytokine storm, neutrophil response, hypoxemia, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which can accelerate pre-existing cardiovascular disease and precipitate acute or chronic heart failure [

3,

5]. The main mechanisms of viral-induced myocardial injury and the pathophysiological processes in heart failure are summarized in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, both original illustrations created by the authors using BioRender.

Heart failure (HF) represents a clinical syndrome characterized by typical symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, and edema, associated with objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction [

6]. It affects approximately 1–3% of the adult population worldwide and more than 10% of individuals aged over 70 years [

6,

7]. In Europe, prevalence continues to rise due to population ageing and the increasing burden of comorbidities. Romania ranks among the EU countries with the highest rates of heart failure, following Hungary, Italy, and Latvia, as reported by the National Institute of Public Health [

7]. The most frequent causes of HF include ischemic heart disease (IHD), hypertension (HTN), valvular heart disease (VHD), cardiomyopathies, and rhythm or conduction disorders [

6,

8]. Despite therapeutic progress, HF remains associated with high morbidity, frequent hospital readmissions, and an unfavourable long-term prognosis, with five-year mortality rates approaching 50% [

9].

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted healthcare delivery, particularly affecting patients with chronic conditions such as HF. Restrictions, resource reallocation, and fear of infection led to delayed hospital presentations, reduced access to diagnostic procedures, and potential underdiagnosis of decompensated HF. Conversely, the direct cardiovascular effects of SARS-CoV-2, combined with psychosocial stress and limited outpatient monitoring, may have worsened clinical outcomes among these patients [

10,

11]. While numerous studies have investigated the cardiovascular complications of COVID-19, most have focused on acute infection rather than its indirect and long-term impact on patients with chronic heart failure.

This study provides a longitudinal perspective on the epidemiological and clinical evolution of heart failure patients across the following three distinct timeframes: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic in a Romanian tertiary emergency hospital cardiology clinic. Unlike most existing reports that focus exclusively on the acute impact of COVID-19 on cardiovascular disease, our analysis captures both the immediate and the delayed effects of the pandemic on chronic heart failure management. The inclusion of a post-pandemic cohort (2023) allows for a comparative assessment of recovery patterns and persistent alterations in cardiac function, comorbidities, and hospitalization characteristics. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate changes in the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients hospitalized with chronic heart failure before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic by comparing data collected from 2019, 2021, and 2023.

Figure 1.

Entry mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 into the cardiac cells (original figure created by Manole Martin with Biorender) [

12].

Figure 1.

Entry mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 into the cardiac cells (original figure created by Manole Martin with Biorender) [

12].

Figure 2.

Pathophysiological mechanisms involved in heart failure (original figure created by Manole Martin with BioRender) [

13].

Figure 2.

Pathophysiological mechanisms involved in heart failure (original figure created by Manole Martin with BioRender) [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective, observational, and comparative study included patients with chronic heart failure and comorbidities hospitalized in the Cardiology Department of Medical Clinic II, Mureș County Emergency Clinical Hospital, in Târgu Mureș, Mureș County, Romania, during the following three distinct periods: January–December 2019 (before the pandemic), January–December 2021 (pandemic), and January–December 2023 (after the pandemic). This study aimed to characterize temporal changes rather than establish causal relationships regarding the demographic, clinical, and epidemiological characteristics of HF patients across these timeframes. All consecutive adult patients (≥18 years old) with a primary diagnosis of chronic heart failure only from the inpatient clinic were included during each study year, and no convenience sampling was applied. During the pandemic period (2021), fewer patients were hospitalized due to stricter admission criteria: only those presenting with a negative SARS-CoV-2 test were admitted for non-emergency hospitalization. Data were collected from patient observation sheets, discharge letters, test reports, and investigations performed during hospitalization.

HF severity was assessed using both the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification (I-IV) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). LVEF was measured by transthoracic echocardiography, calculated in percentage (%), and determined using the following techniques: modified Simpson’s biplane method, visual estimation method and Teichholz method. Measurements were performed by different physicians; Simpons’s biplane method was primarily used, while the visual estimation or Teichholz method were performed only when the image quality was suboptimal. However, we could not state which method was used for every patient.

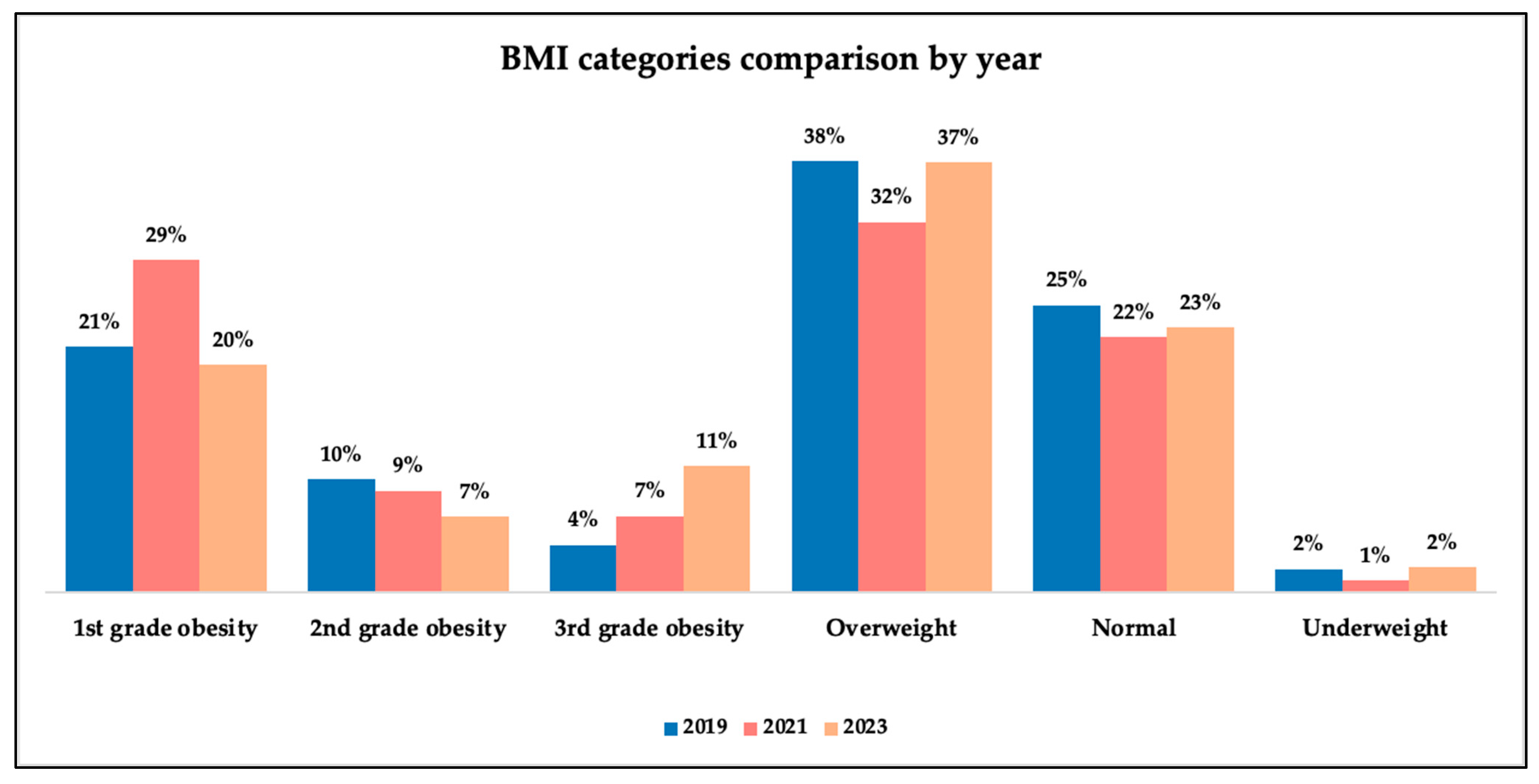

Nutritional status was assessed using only body mass index (BMI) WHO classification.

The NT-proBNP value was measured and considered in this study because it correlates with the prognosis of patients with cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure, VHD, and coronary artery disease (CAD). Normal values were considered according to age as follows:

Comorbidities refer to associated diseases or risk factors such as smoker status.

The category “Valvular heart disease” included the following:

At least one valvular heart disease of at least second degree (mild or higher), demonstrated by transthoracic or transoesophageal echocardiography.

Prosthetic valve of any type.

Physiological traces were not considered for this category.

The patients were not stratified in accordance with the severity of their condition.

Individual COVID-19 infection data were not available; therefore, pandemic-related changes were interpreted as temporal associations rather than direct viral effects. Moreover, many patients likely had asymptomatic forms of COVID-19, which made the causal analysis less relevant, since we cannot know precisely which patient had or did not have the disease.

Sex-stratified and mortality analyses were performed as secondary exploratory analyses and as a part of the epidemiological characteristics.

The following exclusion criteria were applied to ensure cohort homogeneity and minimize confounding: genetic syndromes with cardiovascular involvement, as these represent distinct pathophysiological entities, and history or current malignancy (except basal cell carcinoma), given the potential effects on inflammatory markers and cardiac function and autoimmune disorders due to their association with chronic inflammation (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

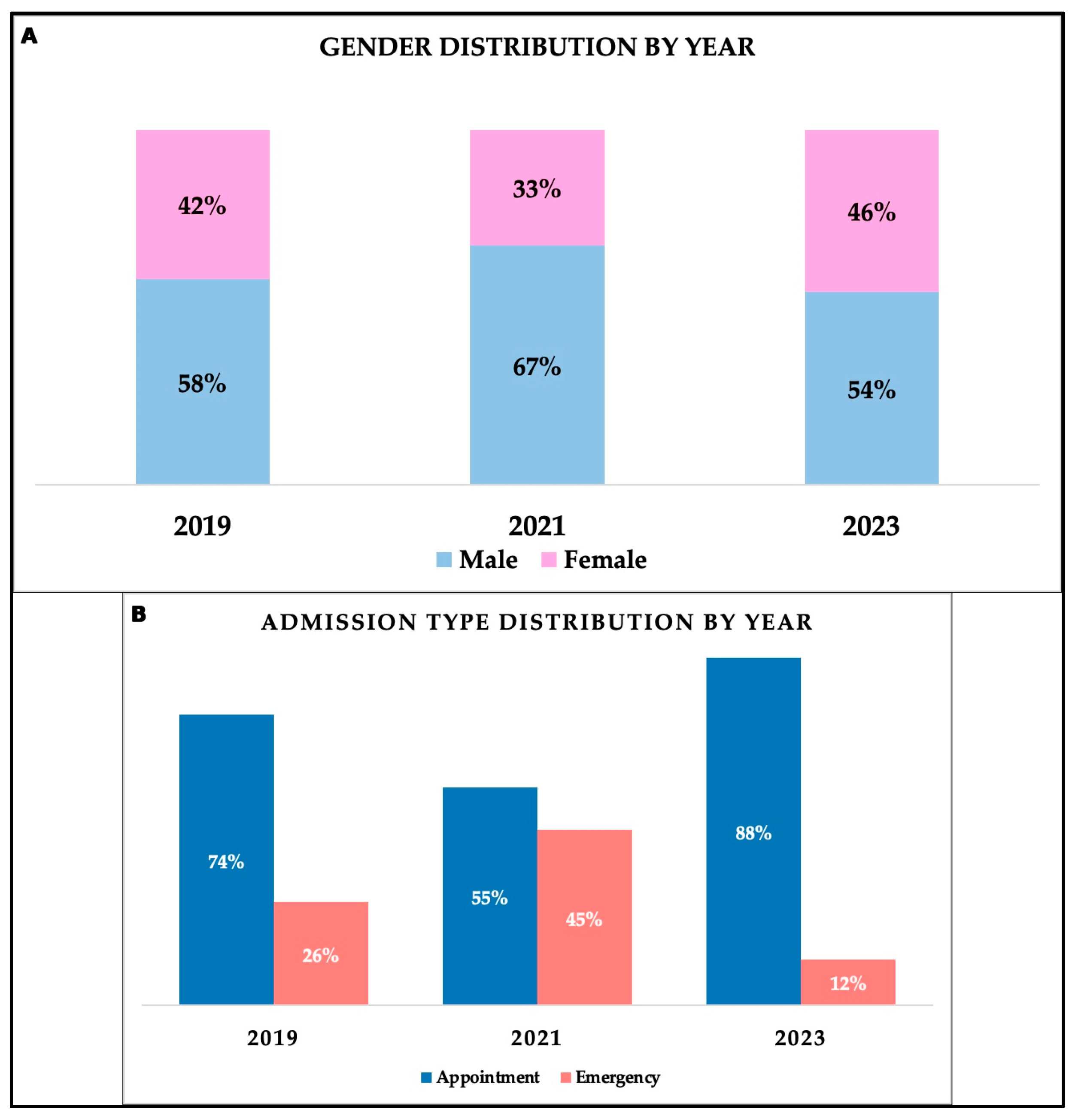

Demographic analysis demonstrated male predominance, and regarding age distribution, significant differences between genders were observed within the entire cohort, with men exhibiting a lower median age (

p < 0.001). This difference was also demonstrated in the Hillingdon study and in the Framingham study, which reported a lower incidence in women aged 50–59 years [

16,

17]. Similarly, a large South Korean study including approximately 8800 patients with HF found that women had a mean age of 71.1 years and men had a mean age of approximately 5 years younger [

18]. As a comparison, females in our study had a median age of 72 years. Patients’ distribution by environment of origin was relatively balanced, with 205 patients originating from rural areas and 201 from urban areas, a pattern consistent across study years. Admission was either by appointment (72.91%) or through the emergency department (27.09%). During the pandemic period, significant differences regarding admission type were observed (

p < 0.001), as suggested by an important rise in emergency admissions in patients during the pandemic (44.6% admitted through emergency department) compared to 26.2% admitted through emergency services in 2019. Following the pandemic, emergency admissions declined substantially to only 11.7%. A study from Romania that assessed the impact of the pandemic on the management of mental health services supports a general decrease in the number of patients who presented to the hospital during the pandemic [

10]. Thus, the fear of being infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus also represented a negative psychosocial factor, independent of the healthcare system and medical staff, on the type of hospitalizations [

10].

Our analysis showed a rise in hospitalization stay during the pandemic period, likely reflecting the reorganization of the public health system during the pandemic and the prioritization of emergency cases. An epidemiological study published in a Romanian scientific magazine examining heart failure hospitalization between 2013 and 2023 reported a national average of hospital stay of 6.5 days [

11]. In contrast, we observed longer hospitalizations, and this can be explained by the sample size (smaller number of patients in the present study), but also by a different regional distribution, with Mureș County having more than double admissions for HF patients compared to other regions of the country [

11]. These differences may also reflect the role of Târgu Mureș as a referral centre with advanced university-based management of patients for advanced or terminal stages of HF; nevertheless, data may reflect regional biases, as our data derive from a single tertiary unit. In 2022, another study that analyzed the impact of heart failure on the European continent was published by the European Society of Cardiology, demonstrating an average duration of hospitalization of the included countries of 8.5 days [

19]. The same article mentions that there is a wide variation in the length of hospitalization from country to country, with Romania reporting an average length of hospitalization around 7 days, most likely due to different diagnostic and management resources and protocols [

19].

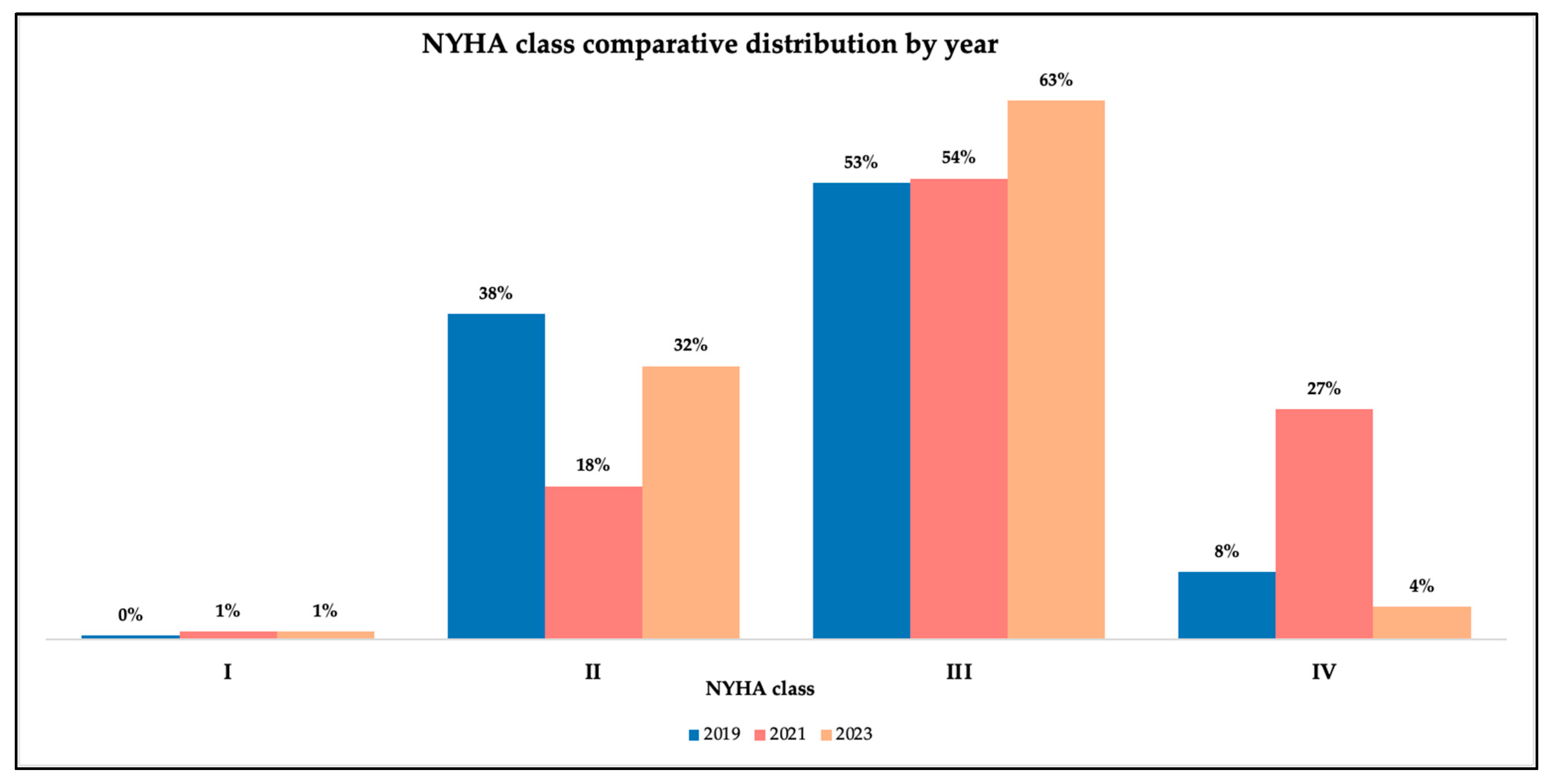

We found a strong, progressively increasing association between symptom severity and length of stay in the hospital, particularly during and after the pandemic. A study during the pandemic on patients with HF and COVID-19 supported longer hospital stays for patients with more severe symptoms, with a median of 20 days for those in NYHA class IV and 10 days for patients in NYHA I, supporting an association between higher NYHA classes and prolonged hospital stay [

20]. Another study that retrospectively observed mortality and hospital stay in patients with HF and LVEF higher than 45% demonstrated increased rates of these indicators for patients who were in NYHA classes III and IV [

21]. In our study, ordinal logistic regression confirmed these findings, with OR indicating a 7.7% increase in the probability of a higher NYHA class per additional hospitalization day in 2019 (OR = 1.077,

p = 0.0136), rising to 11.6% during the pandemic (OR = 1.116,

p = 0.0032) and returning to 7.8% post-pandemic (OR = 1.078,

p = 0.0018). These trends likely reflect both the higher clinical severity of patients from the pandemic period and the subjectivity inherent in NYHA classification.

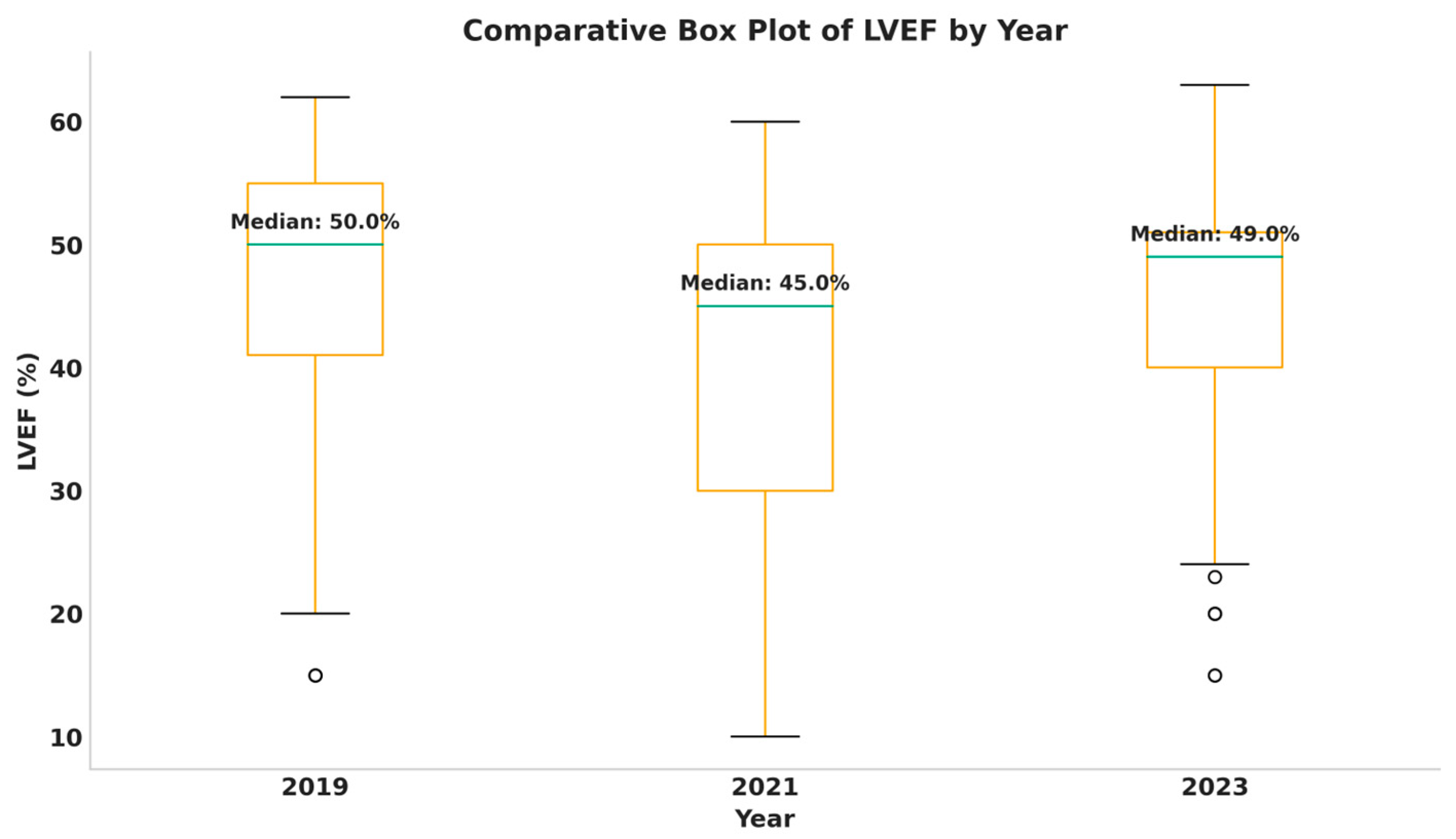

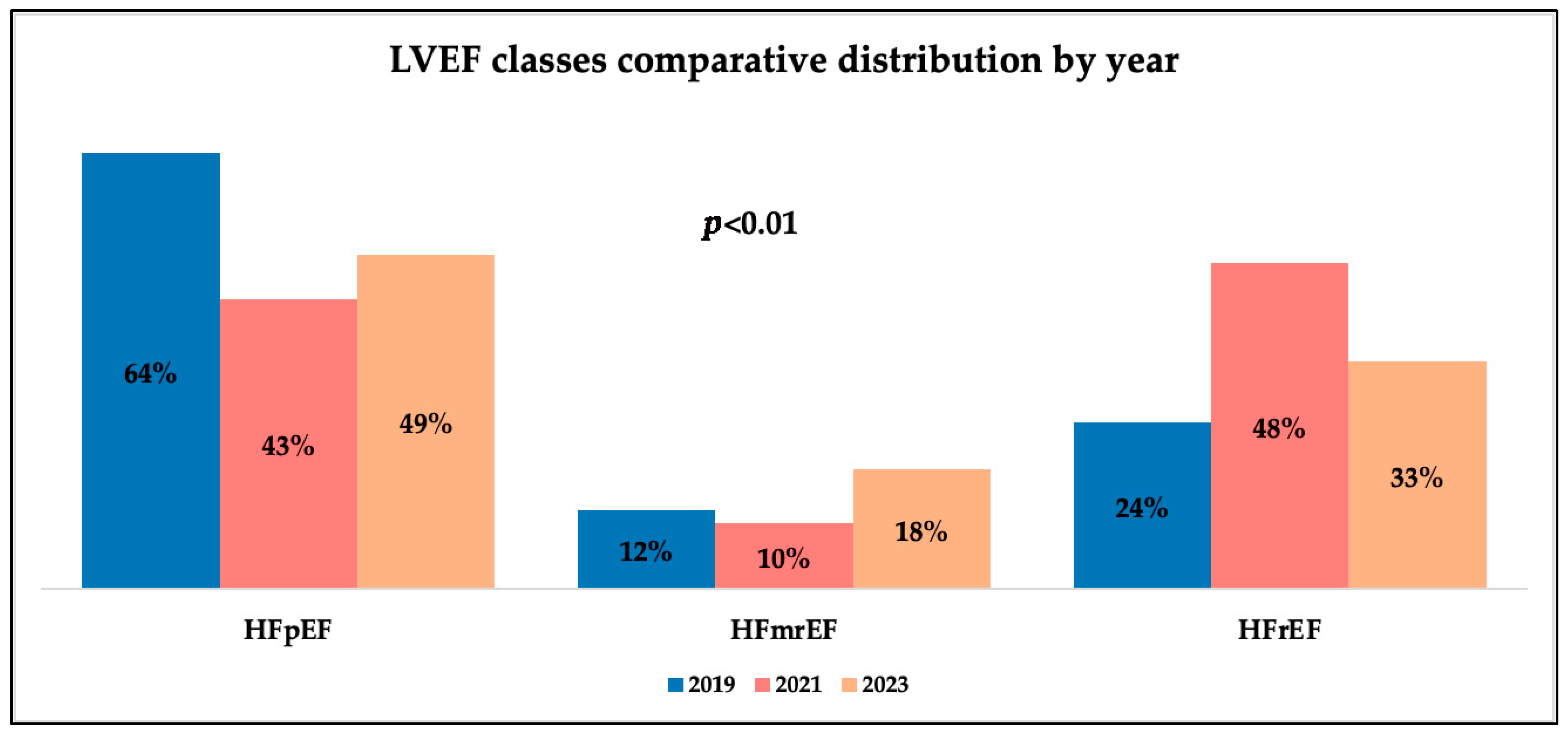

Analyzing patients’ LVEF values, we observed different distributions of LVEF classes by year and gender. We observed that men had significantly lower LVEF values and emergency-admitted patients also exhibited lower values, with a difference of 10% compared to appointment admissions. As has been shown, emergency admissions saw a rise during the pandemic, and alongside this, we observed a decrease in LVEF values throughout the same timeframe. These trends mirror results from recent medical studies, which support an increase in the proportion of patients with lower systolic function during the pandemic, associated with a decrease in those with preserved systolic function and stability in the percentage of patients in the intermediate class over time [

22,

23,

24]. A study focusing on the influence of gender on cardiac function in patients with severe forms of COVID-19 concluded that there were no notable differences, although the majority were male [

25]. The explanation for the fact that LVEF is improved in female patients may suggest a better recovery in the female population after the pandemic or more severe, potentially irreversible, damage to men due to the pandemic. It may also imply the presence of other risk factors that have an increased prevalence among males. Associations between HF phenotypes and demographic variables also revealed interesting patterns. HFrEF was significantly associated with male gender in 2019 (

p = 0.0097), but subsequently it was evenly distributed between men and women post-pandemic. The results are consistent with other studies demonstrating this connection, which mainly support that women with HFrEF have a better survival rate compared to men in the same category and show that premenopausal women most frequently present HFpEF [

26,

27,

28]. Literature further suggests that historical male predominance has diminished over time [

27]. When interpreting these findings, it is important to consider that during the pandemic, we had many epidemiological restrictions that could alter the type of patients. In Romania, only patients who presented a negative status of SARS-CoV-2 infection were admitted for elective investigations or checkups, while emergency admissions involved patients with severe conditions, as quarantine or isolation protocols had to be followed. A study focusing on the influence of gender on cardiac function in patients with severe forms of COVID-19 concluded that there were no notable differences, although the majority were male [

25].

Regarding patients’ comorbidities, we observed a few classic patterns in accordance with HF physiopathology. These findings mirror the literature, which identifies HTN and CAD/IHD as the primary comorbidities of HF [

29]. PH has also been associated with this, along with diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation, especially in patients with HFpEF [

30]. Conduction disorders observed during the pandemic may reflect ventricular remodelling in advanced HF, exacerbated by systemic inflammatory response and incomplete cardiac recovery in previously affected individuals. VHD was the only comorbidity significantly negatively associated with mortality, in fact being a protective factor. Even though this condition is a known predictor of one-year mortality and rehospitalization, particularly when combined with PH [

31], we could not interpret a strong causality effect, as we did not stratify the patients in accordance with VHD severity. Also, these results may be altered by the small groups implied in the statistical calculation, as well as reflecting a regional bias. Studies suggests that patients with a lower severity of VHD may have a better survival rate, and we may have had to deal with a high prevalence of less severe or surgically treated cases of VHD, altering the results [

32,

33].

Atherosclerosis and LBBB showed increased incidence during the pandemic, aligning with other studies where LBBB was associated with mortality rates [

34]. Side effects of certain treatment for COVID-19 have also been described as being responsible for increased rates of intraventricular conduction disorders [

35]. Referrals for the diagnosis of PH and lower incidence rates during and post-pandemic have been reported internationally [

36,

37]. These findings are consistent with the existing literature, identifying HTN, IHD, AF, arrythmias, and MI as major comorbidities and aggravating factors among patients with HFrEF [

38,

39]. We additionally observed significant increases in RBBB and LBBB incidence, especially in men (

p < 0.001 for both disorders). Such patterns reported in other studies may be linked to the systematic inflammatory and cardiac damage induced by COVID-19, which could have promoted ventricular remodelling and delayed post-pandemic cardiac recovery in HF patients [

34,

35].

Among non-cardiovascular comorbidities and risk factors, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and smoker status were most prevalent. These comorbidities are recognized as major contributors to HF progression, especially in patients with HFrEF, being correlated with longer hospitalizations and higher mortality rates [

40,

41]. Anemia, frequently observed in CKD, is primarily attributable to erythropoietin deficiency and disordered iron metabolism [

42]. COPD and smoking are well established to be causally linked, with smoking accounting for approximately 70% of COPD cases [

43].

The analysis of NT-proBNP values revealed significantly higher values among women in 2019, alongside inter-annual differences with each gender. Among men, significant differences were noted between 2019 and 2023 (

p = 0.041), with higher median NT-proBNP levels in 2019 (2132 pg/mL) and between 2021 and 2023 (

p = 0.003), and lower values in 2023 (665 pg/mL). For women, significant differences were identified between 2019 and 2023 (

p = 0.003), with higher median values in 2019 (3983 pg/mL) and between 2021 and 2023 (

p = 0.037), with elevated median values during the pandemic (2747 pg/mL). Prior studies similarly reported higher NT-proBNP concentrations in women, which may indicate gender-specific baselines or support the rationale for gender-tailored therapeutic approaches in the future [

44,

45]. Admission type also influenced NT-proBNP levels each year, with emergency patients presenting significantly higher median levels (5300–5600 pg/mL) each year compared to those from scheduled admissions (400–1200 pg/mL). This pattern may reflect the heightened frequency and severity of cardiac decompensations during the pandemic due to impaired oxygenation and a pro-inflammatory state, both of which increase thrombotic risk with supplementary heart damage [

46], as well as psychosocial factors.

Finally, in-hospital mortality peaked during the pandemic, consistent with other studies reporting an excess mortality rate of approximately +4.5% during the pandemic compared to the expected levels [

47,

48], while other researchers support higher mortality rates exceeding 10%, but with smaller samples [

48]. A French study encompassing 2.7 million acute hospitalizations reported a peak in-hospital mortality of 13% in 2022, with a subsequent 50% decrease in 2023 [

11]. As for Romania, the national in-hospital mortality rate for heart failure patients is around 5% and does not exceed 10%, which is consistent with the findings of the present study [

11]. These findings cannot imply causality by the nature of the study design and data collection.

Study Limitations

This was a retrospective study, and, therefore, variables of interest and potential confounding factors could not be entirely controlled. Moreover, all data were collected from a single Romanian tertiary cardiovascular centre (the Mureș County Emergency Clinical Hospital), which may introduce geographical or cluster bias. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated only for those patients whose records contained the necessary variables, potentially limiting representativeness. Similarly, NT-proBNP values were not available for all patients, which may affect comparability. LVEF measurements were not standardized and were operator-dependent, potentially introducing bias or measurement error, as they were obtained using different methods, by different operators, and on different devices.

Additionally, for certain cardiac conditions, standardized quantitative data on relevant risk exposures (e.g., dietary patterns, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, and treatment adherence) were not systematically recorded or quantified. Collectively, these limitations may reduce the statistical power of the analysis; nevertheless, they underscore the need for further research into how heart failure is diagnosed and treated in the post-pandemic period and how strategies should be tailored according to gender differences.

Consistent information regarding COVID-19 infection or vaccination status was not available for most patients. Therefore, the findings could not be interpreted as evidence of causal relationship with COVID-19, but rather as an observation of temporal changes across the three studied periods.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective and comparative analysis provides an integrated overview of the clinical and epidemiological evolution of chronic heart failure across pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods in a Romanian tertiary care hospital clinic.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, distinct epidemiological, presentation, and management characteristics of heart failure were observed. These patterns were profoundly altered throughout the pandemic. This milestone was a stress factor for patients and healthcare systems around the world, but especially in Romania, disrupting access to care, producing surges in emergency admissions, leading to longer and more heterogenous hospitalization, and causing higher in-hospital mortality. There were changes in heart failure presentation—particularly a rise in the incidence of HFrEF and a decline in HFpEF—along with a reduction in LVEF values, highlighting the blended impact of delayed presentations and more severe decompensation of these chronic patients. Although data from after the pandemic suggested a partial recovery in scheduled care, diagnostic rates, and functional status, persistent arrhythmias, conduction disorders, and comorbidity rebounds emphasize the long-term consequences of the pandemic and epidemiological restrictions, not only as a medical condition, but as a psychosocial disruptor

Differences related to gender were clear through the following results: women presented at older ages, maintained higher LVEF values, and demonstrated specific comorbidity dynamics, whereas men showed higher burdens of conduction disorders. Biomarker analyses confirmed the prognostic value of NT-proBNP and reinforce the differences regarding gender, advanced age (patients over 75 years old), and admission type. These results reiterate the relevance of integrating this investigation as an ordinary test for heart failure patients’ status assessment and the fundamental importance of developing gender and heart failure stage stratification values for these markers. Also, pandemics or other exacerbating factors for heart failure patients should be taken into consideration for refining and developing more accurate biomarkers in patients’ assessment and management.