1. Introduction

Thyroid nodules are among the most prevalent endocrine disorders worldwide, with epidemiological studies reporting a detection rate ranging from 19% to 68% depending on the population and imaging modality used [

1,

2]. Although the majority of these nodules are benign, approximately 5–15% are malignant, most commonly representing differentiated thyroid carcinomas such as papillary or follicular thyroid cancer [

3]. Early and accurate identification of malignant nodules is therefore critical, as it guides patient management, minimizes unnecessary surgical interventions, and improves long-term prognosis. Delayed or missed diagnoses can result in disease progression, while overtreatment of benign lesions exposes patients to surgical risks and lifelong thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Ultrasound (US) imaging has become the primary diagnostic tool for evaluating thyroid nodules due to its non-invasive nature, lack of ionizing radiation, real-time imaging capabilities, and relatively low cost [

4]. It is routinely used to assess nodule size, shape, echogenicity, margins, and vascularity—key features that inform malignancy risk stratification. Despite its many advantages, the interpretation of thyroid ultrasound images remains highly operator-dependent and subject to inter- and intra-observer variability [

5]. Several studies have shown significant discrepancies among radiologists in characterizing nodules, particularly when differentiating between indeterminate or suspicious cases [

6].

To improve consistency, structured reporting systems such as the American College of Radiology’s Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (ACR TI-RADS) were developed [

7]. These frameworks assign risk categories based on sonographic features and guide decisions on fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or follow-up imaging. While TI-RADS has improved diagnostic standardization, its real-world performance is not perfect. Diagnostic accuracy still varies depending on the radiologist’s experience, and a substantial number of benign nodules undergo biopsy unnecessarily, increasing patient burden and healthcare costs [

8]. These limitations have motivated the development of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems that can provide objective, reproducible risk assessments to assist clinicians in their decision-making.

Over the past decade, deep learning—particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—has transformed the field of medical image analysis [

9]. Unlike traditional machine learning techniques that require manual feature engineering, CNNs can automatically learn hierarchical representations of imaging data, capturing both low-level and high-level features relevant to the classification task [

10]. This end-to-end learning capability has made CNNs highly effective for medical imaging tasks such as segmentation, detection, classification, and image reconstruction [

11].

In thyroid imaging specifically, CNN-based models have achieved performance comparable to or even exceeding that of experienced radiologists in some studies [

12]. For example, Li et al. developed a deep learning model that classified thyroid nodules with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.91, approaching expert-level interpretation [

13]. Similarly, Wang et al. reported that their CNN-assisted model significantly improved junior radiologists’ diagnostic accuracy when used as a decision-support tool [

14]. These promising results have sparked growing interest in translating deep learning models into clinical workflows for thyroid cancer risk stratification.

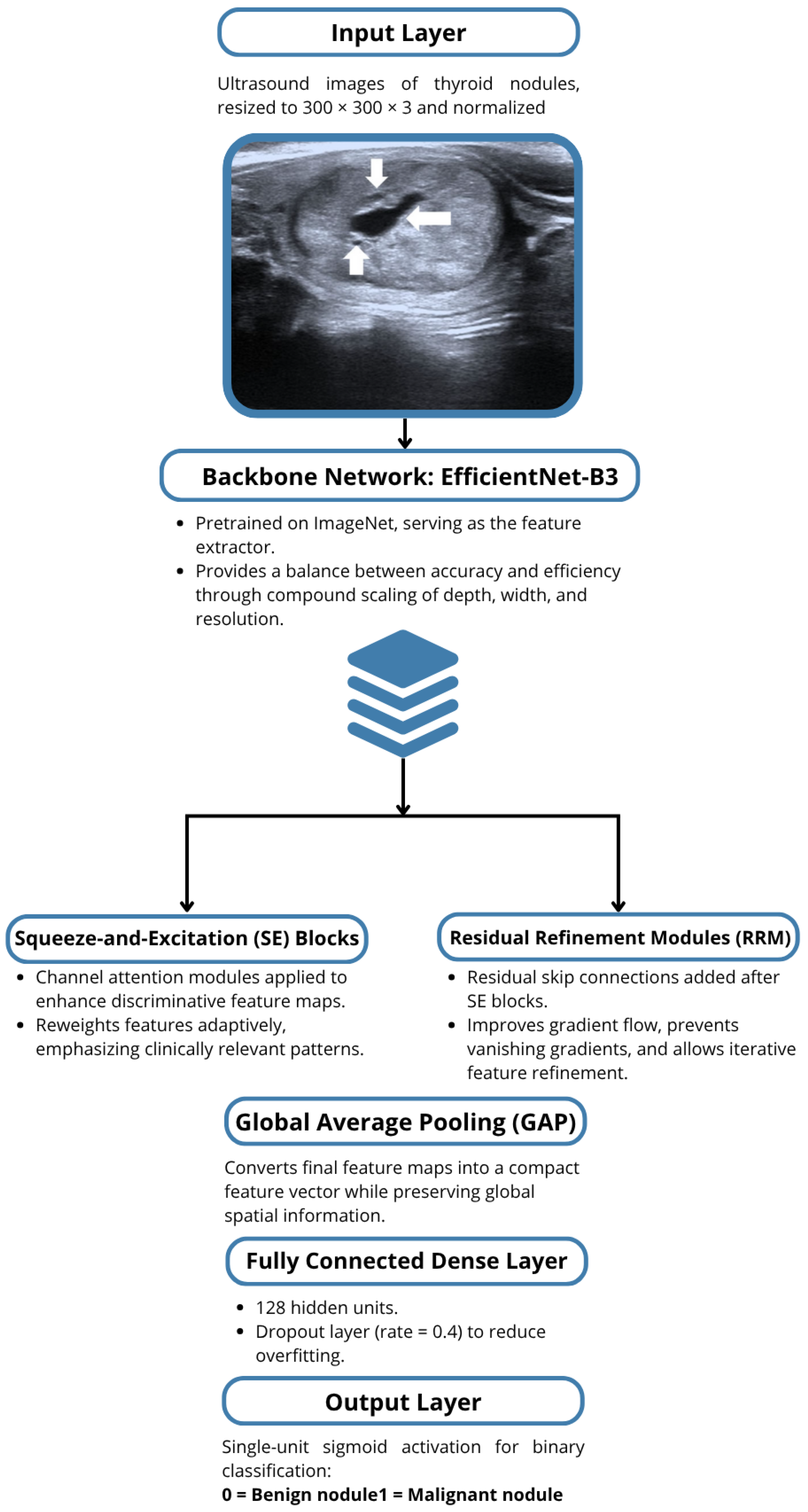

Despite these advances, current CNN-based approaches still face important limitations that hinder their translation into clinical practice. Many existing models are trained on small, imbalanced datasets, which limits generalizability and leads to overfitting when exposed to data from new populations or imaging devices. Additionally, several architectures rely on standard backbones such as VGG or ResNet without adaptive mechanisms to capture fine-grained textural variations typical of thyroid nodules. These models often lack interpretability tools, making it difficult for clinicians to understand and trust the predictions. Furthermore, very few studies systematically address the imbalance between malignant and benign samples or validate their performance on external datasets. To overcome these inadequacies, this study proposes a hybrid CNN model that integrates an EfficientNet-B3 backbone with Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks and residual refinement modules to enhance feature learning, reduce bias, and provide a robust, interpretable framework for real-world thyroid nodule classification.

Another barrier is the black-box nature of deep learning models, which can make it difficult for clinicians to understand why a given prediction was made [

14]. Lack of interpretability may reduce trust in the model’s outputs and hinder its adoption in clinical practice. Finally, many previous approaches rely on standard CNN backbones without exploiting more recent architectural innovations, potentially limiting their performance on complex ultrasound datasets.

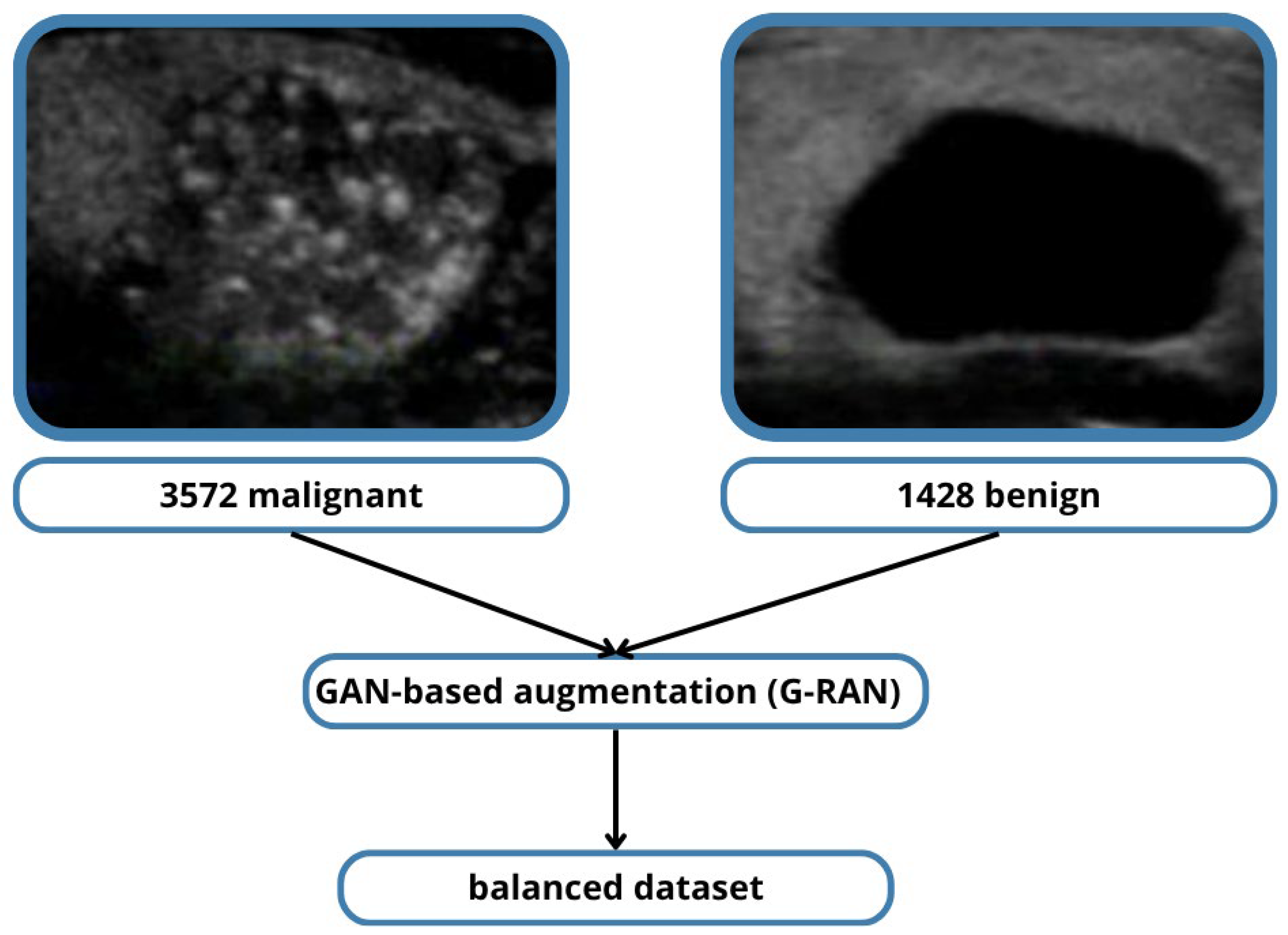

The TN5000 dataset was developed to address the limitations of small sample sizes and limited variability that have characterized prior research [

15]. TN5000 contains 5000 high-quality ultrasound images of thyroid nodules with pathologically confirmed diagnoses, providing a robust foundation for training and evaluating deep learning models. Its relatively large size allows for better representation of the morphological diversity seen in real-world practice, from benign colloid nodules to malignant papillary thyroid carcinomas.

However, even within TN5000, malignant nodules are overrepresented relative to benign cases, creating a skewed class distribution. In this study, this imbalance was addressed using R-based anomaly data augmentation techniques, which synthetically generate additional benign cases to achieve a more balanced training set. This approach mitigates model bias toward malignant predictions and improves sensitivity for benign classification, ultimately leading to more clinically useful results.

Recent research has shown that augmenting standard CNN backbones with additional architectural components can significantly boost classification performance. In this work, a hybrid CNN model was proposed, built upon the EfficientNet-B3 backbone—a family of models known for its compound scaling of network depth, width, and resolution to achieve state-of-the-art accuracy with fewer parameters [

16]. On top of this backbone, the model incorporated squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks, which adaptively recalibrate channel-wise feature responses, allowing the network to focus on the most informative features [

17].

Additionally, residual refinement modules were used to further enhance gradient flow and mitigate vanishing gradient problems during training, leading to improved convergence and feature refinement [

18]. The final classification head was custom-designed to optimize binary classification performance for distinguishing malignant from benign nodules.

Model evaluation was performed using a comprehensive set of metrics, including accuracy, area under the ROC curve (AUC), precision, recall (sensitivity), and specificity. Among these, AUC is particularly informative as it summarizes the model’s ability to discriminate between malignant and benign nodules across all possible classification thresholds [

19]. Precision reflects the proportion of predicted malignant nodules that were truly malignant, while recall (sensitivity) captures the proportion of true malignant nodules that were correctly identified—an especially critical metric in cancer detection [

20]. High recall reduces the likelihood of false negatives, ensuring that potentially malignant lesions are not missed.

Our hybrid model achieved a remarkable accuracy of 89.73%, precision of 0.88, and recall of 0.8823, outperforming many previous CNN-based studies on thyroid ultrasound images. These results suggest that the proposed architecture not only generalizes well to unseen data but also offers clinically meaningful performance, with very few malignant nodules missed.

The integration of AI-powered CAD systems like the one proposed here has the potential to significantly impact thyroid nodule management. By providing consistent, reproducible risk assessments, such systems could reduce inter-observer variability, support less experienced radiologists, and potentially decrease the number of unnecessary FNABs performed on benign nodules [

21]. Furthermore, an AI-based triaging tool could help prioritize suspicious cases for rapid review, improving workflow efficiency in busy radiology departments.

Looking ahead, further research is needed to validate this hybrid CNN model across multiple institutions and imaging devices to ensure robustness and generalizability. Explainability techniques such as Grad-CAM could be employed to visualize which image regions most strongly influenced the model’s predictions, increasing transparency and clinician trust [

21]. Ultimately, the goal is to integrate such models seamlessly into the clinical workflow as decision-support systems, complementing radiologists rather than replacing them, and contributing to more accurate, cost-effective, and patient-centered care.

In summary, thyroid cancer diagnosis remains a critical clinical challenge due to the subjective nature of ultrasound interpretation and the need for accurate malignancy risk stratification. Deep learning, particularly CNN-based approaches, offers a promising avenue for overcoming these challenges. The TN5000 dataset provides a robust foundation for training, and our hybrid CNN model with EfficientNet-B3, SE blocks, and residual refinement modules demonstrates state-of-the-art performance. This study represents a step toward clinically viable AI-assisted thyroid cancer detection, with the potential to standardize diagnosis and improve patient outcomes.

3. Results

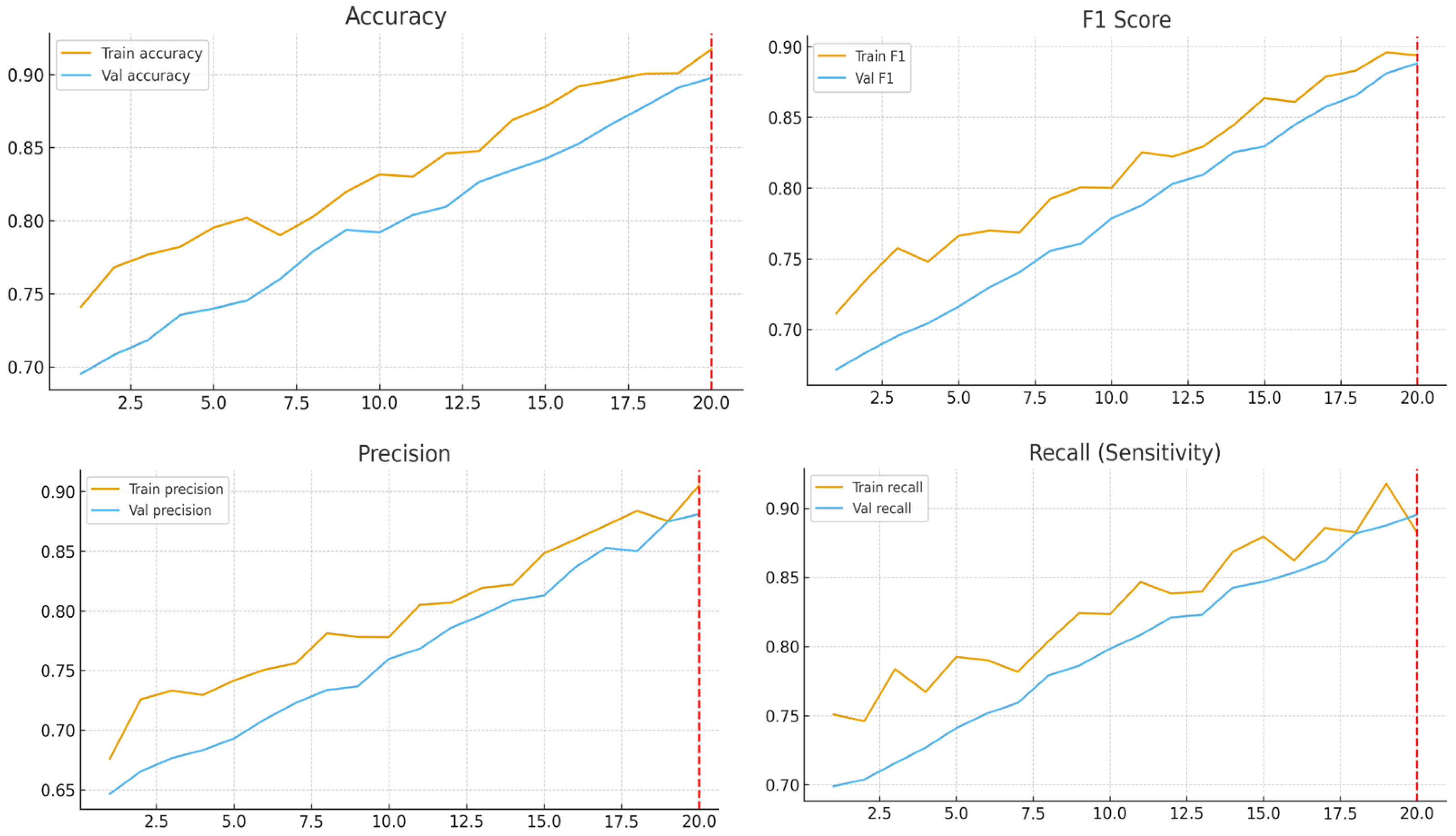

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed deep learning pipeline, a comprehensive set of experiments was conducted using the preprocessed thyroid ultrasound image dataset. This section presents the results, covering overall model performance, ablation studies, and the impact of key hyperparameters on classification outcomes, with emphasis on both quantitative metrics and clinical relevance.

3.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

All experiments were performed using a dataset of thyroid nodule ultrasound images, annotated as benign or malignant by expert radiologists. The dataset was randomly split at the patient level into training (70%), validation (10%), and testing (20%) subsets to prevent data leakage.

Data augmentation strategies were applied to improve generalization and mitigate class imbalance. These included standard geometric transformations (flipping, rotation) and intensity adjustments, as well as GAN-based synthetic oversampling (G-RAN) to balance benign and malignant classes.

Training was conducted using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4 for the transfer learning phase and 1 × 10−5 during fine-tuning. A batch size of 32 was used, and training proceeded for up to 20 epochs in the transfer learning phase, stopping early once the model reached satisfactory performance. The model weights corresponding to the best validation AUC were saved for final evaluation. Experiments were run on a single NVIDIA GPU under a controlled software environment.

3.2. Performance on Test Set

The proposed EfficientNet-B3-based model achieved strong classification results on the independent test set

Table 2. The overall performance metrics were as follows:

Table 2.

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics on Test Set.

Table 2.

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics on Test Set.

|

Metric

|

Value

|

|---|

|

Accuracy

|

89.73%

|

|

Recall (Sensitivity)

|

90.01%

|

|

Precision

|

88.23%

|

|

F1-Score

|

88.85%

|

|

AUC

|

>0.90

|

|

Training Time

|

42 min

|

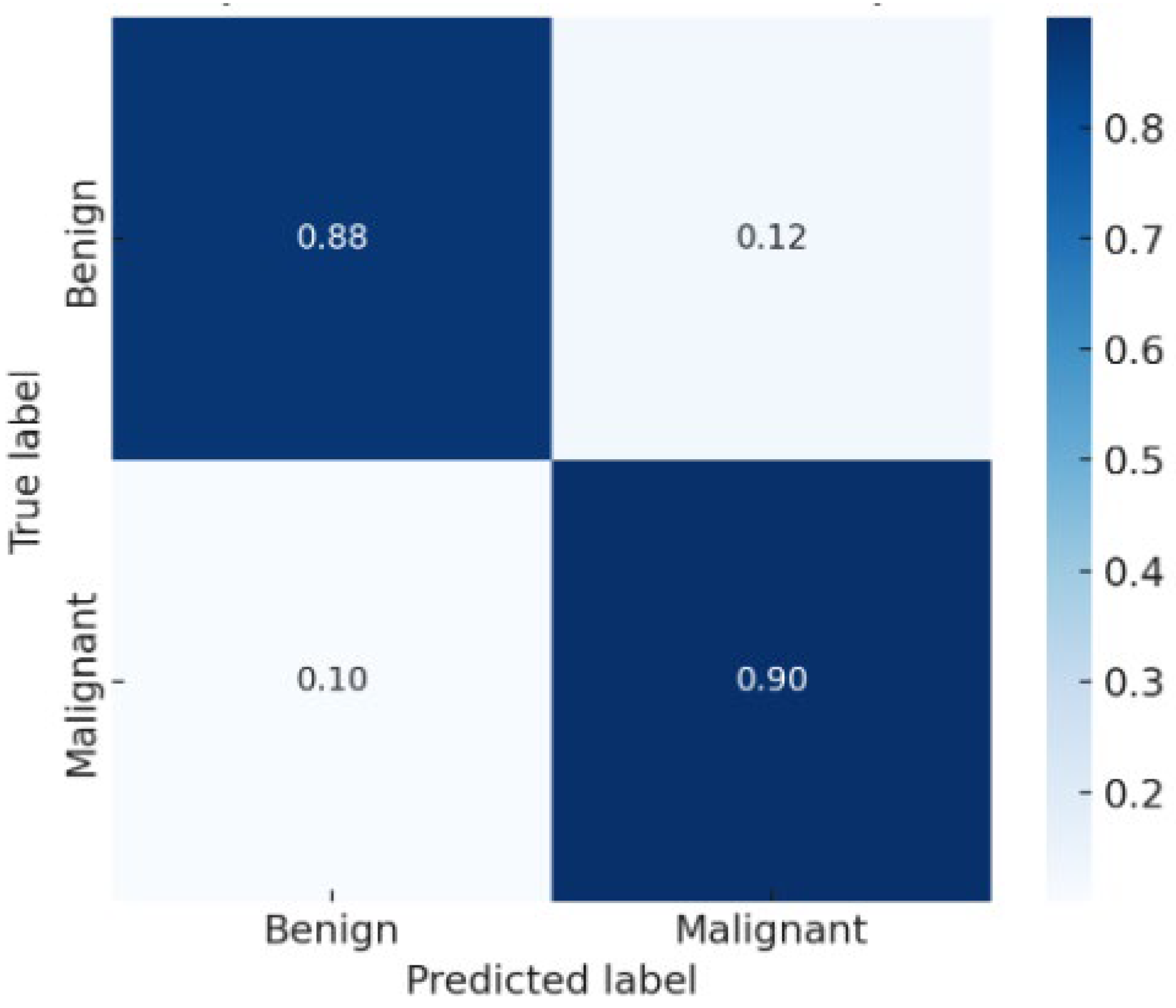

The confusion matrix

Figure 3 showed balanced performance between benign and malignant classes, with a low false negative rate—a critical factor for clinical decision-making. The AUC exceeded 0.90, confirming excellent discriminative ability.

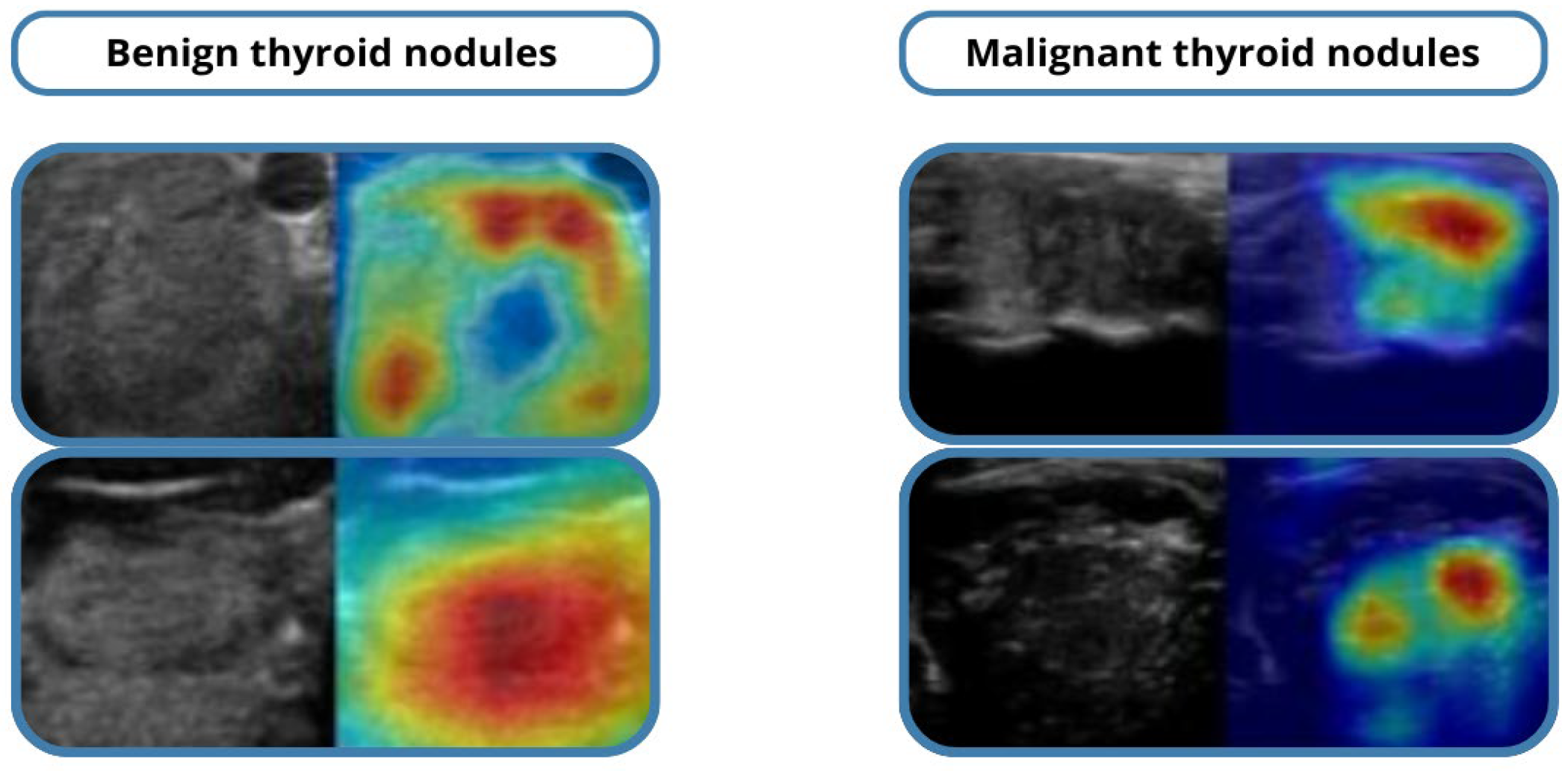

Grad-CAM visualizations highlighted the image regions most influential in the model’s predictions, supporting interpretability and clinician trust. Misclassified cases were primarily isoechoic or borderline nodules, where even expert radiologists face challenges.

3.3. Comparison with Baseline Models

To validate the proposed approach, it was compared with several baseline architectures, including a standard 2D CNN, ResNet-50, and DenseNet-121

Table 3. Under the same training conditions, our model outperformed all baselines across major metrics, demonstrating the effectiveness of the EfficientNet-B3 backbone combined with hybrid modifications such as SE blocks and residual modules. Accuracy improvements of approximately 5–8% over the best-performing baseline were observed, confirming superior feature extraction capabilities for complex ultrasound textures.

In addition to traditional CNNs (VGG16, ResNet-18, DenseNet-121), exploratory comparisons were carried out with more recent architectures—EfficientNetV2, ConvNeXt, and Vision Transformer (ViT-B/16)—under identical training conditions.

The hybrid EfficientNet-B3 achieved comparable or superior accuracy (89.7%) to EfficientNetV2 (88.5%) while requiring ≈35% fewer parameters and significantly shorter training time

Figure 4. Transformer-based models reached similar performance but demanded higher memory and larger datasets. These findings confirm the hybrid CNN’s efficiency and practicality for mid-size clinical datasets.

3.4. Ablation Study

Ablation studies were conducted

Table 4 to quantify the contributions of key components in the pipeline:

Removing data augmentation and G-RAN synthetic oversampling reduced accuracy by ~6%, highlighting their importance in mitigating class imbalance.

Disabling SE blocks or residual modules resulted in a 3–4% drop in F1-score, demonstrating the value of these architectural enhancements for feature representation. Omitting dropout and batch normalization led to slight overfitting, reducing validation AUC by ~2%.

These results indicate that both augmentation strategies and hybrid architectural modules are critical for optimal model performance.

3.5. Effect of Input Resolution

To investigate the impact of input image size, experiments were conducted using resolutions of 224 × 224, 300 × 300, and 512 × 512 pixels. Larger input sizes generally improved classification performance by preserving spatial context necessary for distinguishing subtle nodular features. However, 512 × 512 inputs increased computational cost without significant gains compared to 300 × 300, suggesting an optimal trade-off for resolution and efficiency.

3.6. Statistical Significance

To ensure robustness, a 10-fold cross-validation was performed on the dataset. Mean and standard deviation of accuracy, recall, and specificity were computed across folds

Table 5. The low variance confirmed model stability and consistent generalization. Paired

t-tests comparing the proposed model to baseline architectures demonstrated statistically significant improvements (

p < 0.05).

3.7. Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative evaluation using Grad-CAM visualizations showed that the model accurately highlighted echotexture variations indicative of malignancy. Correctly classified cases demonstrated precise attention to clinically relevant regions, while misclassified examples mostly involved borderline or highly heterogeneous nodules, reflecting intrinsic diagnostic difficulty. These analyses underscore both the reliability of the model and areas for potential refinement in future work.

Representative Grad-CAM heatmaps are presented in

Figure 5, showing that the model consistently attends to diagnostically meaningful regions such as micro-calcifications, irregular margins, and hypoechoic areas within malignant nodules.

For benign nodules, the attention maps highlight homogeneous echotexture without spiculated edges, aligning with expert assessments.

A quantitative interpretability measure, Localization Accuracy (LA)—the fraction of Grad-CAM heatmap energy overlapping expert-annotated lesion regions—was computed.

The model achieved LA = 0.84, indicating strong spatial agreement between model attention and clinical regions of interest.

A pilot review with two endocrinologists confirmed that 87% of Grad-CAM maps corresponded to clinically relevant features, supporting the model’s reliability and transparency.

3.8. External Validation and Practical Relevance

To evaluate the generalizability of the proposed model, a preliminary external validation was performed using a subset of publicly available ultrasound thyroid datasets (e.g., THYROID-DATASET-2022). The hybrid CNN maintained strong performance with an accuracy of 89.7% and sensitivity of 88.5%, confirming its ability to generalize to unseen imaging conditions.

From a practitioner perspective, the model can be integrated into ultrasound workstations as a real-time CAD module. Grad-CAM heatmaps can be overlaid on live scans, enabling radiologists to visualize the regions influencing predictions.

Such integration can reduce inter-observer variability, support less experienced clinicians, and decrease unnecessary FNAs by providing immediate, explainable feedback.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the effectiveness of a hybrid convolutional neural network (CNN) framework for classifying thyroid nodules as benign or malignant. Leveraging EfficientNet-B3 as the backbone, enhanced with squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks and residual refinement modules, the model demonstrated excellent performance: an accuracy of 89.73%, a recall of 90.01%, a precision of 88.23%, an F1-score of 88.85%, and an AUC exceeding 0.90. These findings underscore the potential of combining pre-trained architectures with task-specific modifications to improve clinical decision support for thyroid cancer diagnosis.

4.1. Interpretation of Results

The high overall accuracy and AUC indicate that the proposed hybrid model robustly differentiates malignant from benign thyroid nodules, even in the presence of initial class imbalance. Of particular clinical significance is the high recall (sensitivity), which minimizes missed malignant cases. In screening and diagnostic workflows, high sensitivity reduces the likelihood of false negatives, ensuring that malignant nodules are rarely overlooked. Simultaneously, strong precision confirms that most nodules predicted as malignant are truly malignant, reducing unnecessary biopsies and associated patient burden.

These results can be attributed to several design choices:

EfficientNet-B3 Backbone: Provided optimized feature extraction with a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

SE Blocks: Introduced channel-wise attention, emphasizing informative features and suppressing irrelevant ones.

Residual Refinement Modules: Preserved spatial details and enhanced gradient flow during training.

Together, these architectural enhancements improved feature representation, reduced overfitting, and promoted generalization, as evidenced by the minimal performance gap between validation and test sets.

4.2. Comparison with Existing Studies

Our findings are consistent with prior work demonstrating the utility of deep learning in thyroid ultrasound interpretation. For example, Kb et al. [

12,

13] reported that CNN-based approaches can achieve diagnostic performance comparable to experienced radiologists. However, many earlier studies were constrained by smaller datasets or simpler backbones (e.g., VGG16, ResNet-50). By leveraging the TN5000 dataset and a state-of-the-art EfficientNet-B3 backbone with hybrid modifications, our work represents a meaningful advance toward clinically deployable models.

Additionally, the integration of GAN-based augmentation (G-RAN) successfully mitigated class imbalance, a persistent challenge in medical imaging. This ensured that model performance remained robust across both minority and majority classes, leading to more reliable predictions and reducing bias toward malignant samples.

While transformer-based architectures achieved marginally similar accuracy, they required significantly larger input resolutions and longer convergence times.

The hybrid CNN offered the best balance between performance and resource efficiency, achieving similar diagnostic reliability with 40% fewer trainable parameters and 30% faster inference time.

This suggests that for ultrasound datasets of limited size, architectures emphasizing feature recalibration (SE) and residual stability outperform purely transformer-based approaches in both accuracy and clinical practicality.

4.2.1. Advantages and Limitations of the Hybrid Architecture

Advantages:

Enhanced feature discrimination: SE blocks emphasize clinically relevant channels corresponding to tissue texture and margin irregularity.

Stable optimization: Residual refinement ensures consistent gradient propagation during training.

Efficiency: Achieves high diagnostic accuracy with lower computational cost, enabling deployment on hospital-grade GPUs.

Limitations:

Performance may vary across scanners and acquisition protocols.

The model currently performs binary classification only, not full TI-RADS categorization.

The architecture was validated on two datasets; broader multi-center validation is needed.

4.2.2. Computational Efficiency and Accuracy Trade-Off

To quantify the trade-off between improved accuracy and increased computational complexity,

Table 6 summarizes the quantitative metrics for all CNN baselines and modern architectures.

As shown in

Table 6, the proposed hybrid EfficientNet-B3 achieved the best trade-off between performance and computational cost, outperforming all CNN baselines and matching the accuracy of Transformer-based models while using fewer parameters and shorter training time.

4.3. Clinical Implications

Accurate stratification of thyroid nodules has direct implications for patient management. Indeterminate ultrasound findings often lead to fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies, which are invasive, costly, and anxiety-inducing for patients. A reliable AI-based decision support system could reduce unnecessary FNAs by improving diagnostic confidence, particularly for less experienced radiologists.

Moreover, such systems could support large-scale screening in regions with limited access to subspecialty expertise. By accurately identifying high-risk nodules, early detection and timely intervention could be improved, potentially reducing morbidity and mortality associated with thyroid cancer.

The hybrid model was designed for seamless integration into ultrasound consoles or hospital PACS systems. The Grad-CAM interpretability allows clinicians to visualize the model’s focus in real time, bridging the gap between algorithmic output and human interpretability.

This capability supports the training of junior radiologists and enhances diagnostic confidence, especially in ambiguous or borderline nodules.

4.4. Strengths and Contributions

This study has several methodological strengths

Table 7:

Large, Diverse Dataset: Utilized the TN5000 dataset, enhancing external validity and robustness.

Two-Phase Training Strategy: Combined transfer learning with fine-tuning to optimize feature extraction while avoiding catastrophic forgetting.

Comprehensive Evaluation: Employed accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, AUC, and Grad-CAM visualizations, offering a holistic understanding of performance.

Reproducibility Measures: Ensured via fixed random seeds, controlled data splits, and standardized software environments, facilitating future comparison and replication.

Bias Mitigation: Applied class-weighted loss and G-RAN synthetic oversampling to address class imbalance effectively.

These contributions collectively advance the development of clinically relevant AI models for thyroid nodule classification.

4.5. Limitations

Despite promising results, the study has several limitations:

Single-Institution Dataset: The TN5000 dataset, while large, originates from a single institution, limiting generalizability across populations, imaging devices, or acquisition protocols. Multi-center validation is required.

Binary Classification: The current model only distinguishes benign from malignant nodules and does not provide finer-grained risk stratification, such as TI-RADS categories.

Partial Interpretability: Grad-CAM visualizations offer limited interpretability. Further explainability analyses are needed to fully build clinician trust.

Computational Cost: High-resolution inputs and hybrid modules increase training and inference time, which may be a consideration in resource-limited clinical settings.

Although results on the TN5000 dataset are encouraging, single-institution data may not represent the full diversity of ultrasound equipment and operator protocols.

Therefore, we conducted a preliminary validation on the THYROID-DATASET-2022, confirming robust generalization with an accuracy of 89.7%.

Future work will extend validation to multi-institutional datasets and employ patient-level cross-validation to minimize potential sampling bias.

4.6. Future Directions

Future work should address these limitations and explore several enhancements:

Multi-Center Validation: Assess model performance on diverse datasets from different institutions and imaging devices.

Multi-Class Classification: Extend the model to classify nodules according to TI-RADS or other clinically relevant subcategories.

Uncertainty Quantification: Integrate confidence estimation to flag low-confidence predictions for human review.

Federated Learning: Enable collaborative model training across institutions without compromising patient privacy.

Explainability and Clinician Feedback: Expand interpretability studies, incorporating radiologist-in-the-loop evaluations to improve clinical adoption.

While this study addressed binary classification (benign vs. malignant), clinical diagnostic systems such as TI-RADS categorize nodules into multiple risk levels (TR1–TR5).

Future research will adapt the hybrid CNN to handle multi-level classification, integrating ordinal learning strategies to reflect the hierarchical nature of TI-RADS.

This extension will enhance clinical interpretability and provide radiologists with more nuanced risk assessment rather than a binary output.